Yearly Archive2009

Commentary 24 Jul 2009 07:30 am

Magoo’s Carol & Little hop

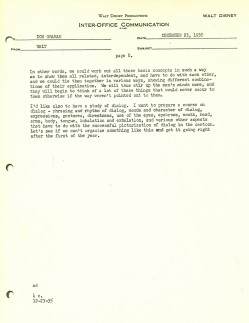

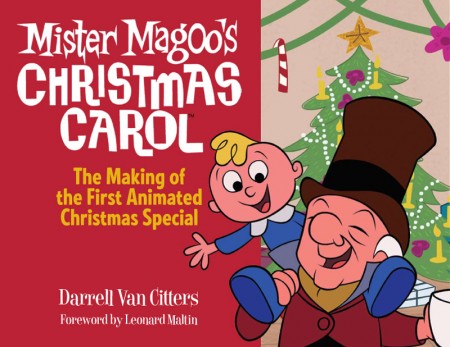

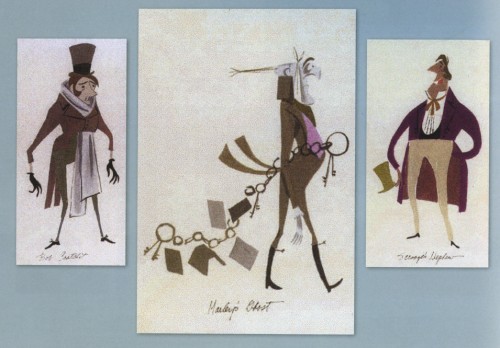

- I just received my copy of Darrll Van Citters’ new book, Magoo’s Christmas Carol: the making of the First Animated Christmas Special. This is a treasure. If you have any affection for this show or for animation in general I can only say GET THIS BOOK.

- I just received my copy of Darrll Van Citters’ new book, Magoo’s Christmas Carol: the making of the First Animated Christmas Special. This is a treasure. If you have any affection for this show or for animation in general I can only say GET THIS BOOK.

It’s beautiful; packed with storyboard, animation drawings, backgrounds and photos. Lots and lots of photos of the cast, crew, musicians, animators. Everything. It’s gorgeous. Darrell did the research, got the background material and put it all together in a beautiful package. He put his own money into it and didn’t get cheap at any stage of the process.

I haven’t read the book yet (I literally just received it), but I’m ready to push my work aside to start reading – that’s how anxious I am. Of course, I won’t do that, but I will write more and in length after I do read it.

I just wanted you to know that you should rush to get it. It’ll be sold at the San Diego Comic Con. For those, not able to get there just hit this link, and it’ll take you to the store where you can get copies signed or not.

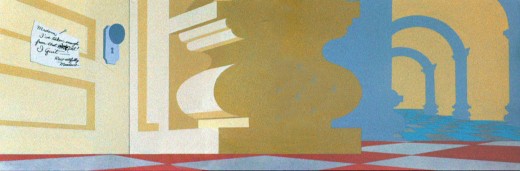

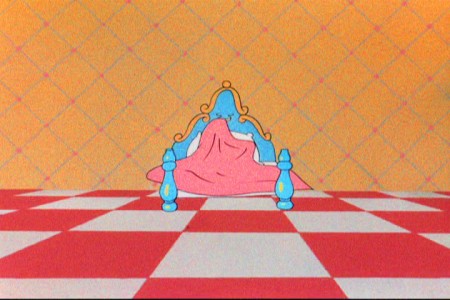

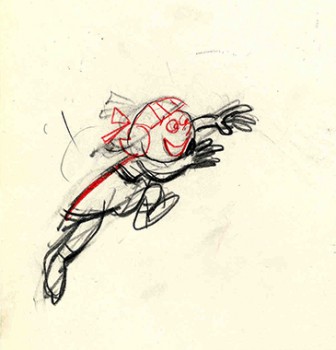

This is a tiny sample of the art from the film’s production, though my scan doesn’t do it justice. The picture is better as printed in the book:

____________________

- If you want to see pure character in motion, take a look at the HBO documentary currently  airing, the biography of Ted Kennedy. Teddy, In His Own Words is an excellent work that really gets into the history of this man and his family. However, there is one scene that keeps reverberating in my memory.

airing, the biography of Ted Kennedy. Teddy, In His Own Words is an excellent work that really gets into the history of this man and his family. However, there is one scene that keeps reverberating in my memory.

Ted had almost died in a plane crash; he broke his back. He was laid up in a hospital and at his home for a very long time. Finally, there was a point where he was to return to Congress.

The camera shows footage of Bobby Kennedy pacing outside the Capitol, waiting for his brother to arrive. Up pulls a big old car, and Bobby knows it’s his brother.

He starts to walk very quickly to meet Teddy and in that fast pace, Bobby actually does a miniscule stop and hop mid walk to greet him.

That little hop is so beautiful and endearing and emotional that I was just completely taken with the guy. It’s not too far from Gerald McBoing Boing’s walk in the original film, but here a real person is doing it, and the impetuous move is so delightful in its spontaneity.

If you get a chance, watch the show (no matter your political persuasion) these guys are history and there’s a big story of the last half of 20th Century here. It’s quite amazing.

And watch for Bobby Kennedy’s little jump; it’s so innocent and human.

There’s so much more to learn about animation by watching real life. Too many people these days put all their attention into studying animation and ignoring the real thing. That wasn’t the case with the real masters, and it’s no different today. Watch what you’re caricaturing.

Here’s the schedule of the documentary for July & August, but it’s also on their On Demand feature so you can watch it anytime.

Articles on Animation &Comic Art 23 Jul 2009 07:22 am

Keane Family Circus

- I’ve had a bizarre attraction to Bil Keane‘s comic strip, The Family Circus. I was always sure that this strip might make a good animated show for television. In fact, A Family Circus Christmas directed by Al Kouzel was a good show. It came as a surprise when I first saw it, though there’s no reason I should have been. The story was first rate. The real surprise came years later when I learned that Bil’s son, Glen, had become one of the finest of the new-generation animators at Disney.

- I’ve had a bizarre attraction to Bil Keane‘s comic strip, The Family Circus. I was always sure that this strip might make a good animated show for television. In fact, A Family Circus Christmas directed by Al Kouzel was a good show. It came as a surprise when I first saw it, though there’s no reason I should have been. The story was first rate. The real surprise came years later when I learned that Bil’s son, Glen, had become one of the finest of the new-generation animators at Disney.

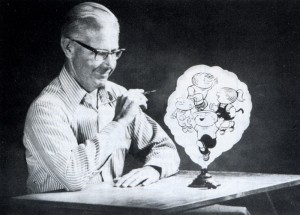

Bil Keane was interviewed in the Dec. 1975 issue of CARTOONIST PROfiles by the magazine’s editor, Jud Hurd, and I post it here:

BIL KEANE is one of those fairly rare cartoonists who is just as funny on the speaking platform as he is onpaper in the two panels, THE FAMILY CIRCUS and CHANNEL CHUCKLES, he creates for THE REGISTER & TRIBUNE SYNDICATE. We heard another of Bil’s great talks again recent-ly, which prompted us to ask him some questions ahout cartooning for our magazine. BU and his famih- live in Paradise Valley, near Phoenix, Arizona.

BIL KEANE is one of those fairly rare cartoonists who is just as funny on the speaking platform as he is onpaper in the two panels, THE FAMILY CIRCUS and CHANNEL CHUCKLES, he creates for THE REGISTER & TRIBUNE SYNDICATE. We heard another of Bil’s great talks again recent-ly, which prompted us to ask him some questions ahout cartooning for our magazine. BU and his famih- live in Paradise Valley, near Phoenix, Arizona.

Q: Some time ago we did an interview with you that has caused a lot of comment. Your answers were hilariously funny, but not too informalive. l’d like this tobea serions interview that imparts to our readers the inner workings of Bil Keane.

KEANE: Fine. Which way to the X-ray machine?

Q: Seriously, could you give us a brief resumé of your art background?

KEANE: It’ll be quite brief because I never studied art. I taught myself to draw while I was in high school by imitating the cartoonists whose work I admired.

Q: Who were they?

KEANE: Each month I would have a different New Yorker magazine idol… George Price, Richard Decker, Peter Arno, Robert Day, Whitney Darrow, Barlow, Wortman… This was in the late thirties. l’d practice each style and technique until, in my mind, my drawings looked “similar” to the master. I still think this is an excellent way to develop a style. Eventually your own “thing” will emerge. I enjoyed studying cartoonists’ styles and learned to recognize them like handwriting. I used to play a game when Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, or American Magazine would arrive in the mail. As l’d turn a page on which there was a cartoon, l’d quickly cover the part of the cartoon bearing the signature and name the cartoonist who had made the drawing. Then, l’d lift my hand to see if I was right. I had a very high rate of accuracy. l’d be fooled only by a newcomer. I also became a fanatic cartoon clipper. I eut out every magazine cartoon I could find and pasted them in huge scrapbooks. I remember one time I was thrown out of a public library for slicing cartoons out of the current magazines with a razor blade. In fact, it was last week!

Q: Were magazine cartoons the only ones thaï interested you, or did you follow the newspaper cartoonists too?

KEANE: I never was an avid fan of the comic strip guys although I certainly admired most of the big ones. However, I had a real penchant for the newspaper panel cartoonists. George Lichty was my all-tirne favorite. I also liked H. T. Webster, Fontaine Fox, J. R. Williams, Gène Ahern and particularly Clare Briggs. Another genius to me was J. Norman Lynd who drew “Vignettes of Life.”

Q: Do you feel that most magazine gag cartoonists can develop a successful syndicated feature?

KEANE: Not necessarily. Some cartoonists are prolific and can turn out volumes of material from which a magazine editor may select the best. A syndicated cartoonist, for the most part, is his own editor. Unless he has the ability to discern which of his creations are good and which are poor, his feature will not hâve the batting average required to maintain success. I hâve seen highly successful magazine men fall fiât on their faces when attempting a 6 day a week feature done entirely by themselves.

Q: Some people write inspirations for cartoon ideas on the backs of old envelopes. Russell Myers carries a lape recorder and talks into it when he thinks of a “Broom Hilda” idea.

What system do you use for this?

KEANE: I don’t think of many “Broom Hilda” ideas, but when I do, I talk into the back of an old envelope.

Q: You promised this would he a serious interview.

KEANE: Frankly, for “Family Circus”, the only gimmick I use to think of ideas is thumbing through family type magazines where articles, pictures, ads, columns, etc., will suggest a setting or bring to mind one of the incidents that has happened in our home in the past. Given a specific setting or situation I can readily create a child’s reaction to it. I have a childish mind.

Q: Do you then write the caption or do the drawing first?

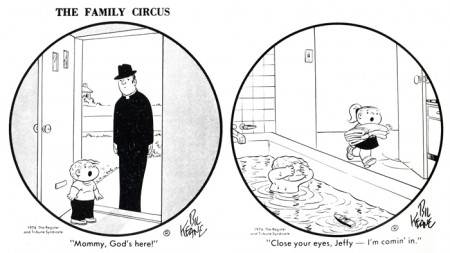

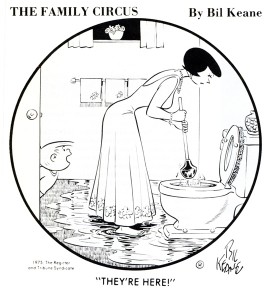

KEANE: It works both ways. Frequently the idea comes from a quote or phrase that is typical, or a youngster’s mispronounced word, or a childish musing such as: “Mommy, I need a hug.” Then all I do is create a cartoon that best fits with the line. At other times the picture depicts the identifiable scene such as a little girl dressed in her mother’s clothes, or a little boy running into the house with a bug in ajar, etc. Then I need to create a line to go with the illustration.

In most cases the caption is not really finalized till I am through with the drawing. As I am penciling the cartoon I keep saying the line over and over again to myself, changing it slightly to see how it sounds in various versions. I think it is terribly important in the kind of thing I do to have what a child says, or Mommy says, or whoever, sound natural, unmanufactured and clear.

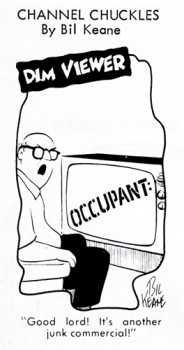

Q: In “Channel Chuckles” you use a different type of humor than you do in “Family Circus.” Would you comment on this?

KEANE: “Channel Chuckles” humor is more satirical, zany and topical than “Family Circus.” The latter utilizes the identifiable, typical, “our kids have done the same thing” type of humor. Another entirely different field of humor that I like is the pun. I developed a solid background in this type of humor as a young boy when I was an avid collector of the old College Humor magazines that had been published in the 20′s and 30′s where piuis ran rampant. When I worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin in the late 40′s and during the 50′s I developed a Sunday color feature called “Mirth-quakers” which featured illustrated puns and the old “he-she” jokes (Sample: “Many big men born in this town?” “Nope, only little babies!”). For a few years, I drew a feature for the Saturday Evening Post “Pun-Abridged Dictionary. When my Sunday “Family Circus” page started in 1′ appended it with a weekly panel “Sideshow”, consisting of reader-contributed puns. The 25,000 letters a year that this feature drew, as well as the enthusiastic response other pun features convinced me that thi many pun-lovers in the country. (And quite few in the city, too, but they won’t admit it.)

KEANE: “Channel Chuckles” humor is more satirical, zany and topical than “Family Circus.” The latter utilizes the identifiable, typical, “our kids have done the same thing” type of humor. Another entirely different field of humor that I like is the pun. I developed a solid background in this type of humor as a young boy when I was an avid collector of the old College Humor magazines that had been published in the 20′s and 30′s where piuis ran rampant. When I worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin in the late 40′s and during the 50′s I developed a Sunday color feature called “Mirth-quakers” which featured illustrated puns and the old “he-she” jokes (Sample: “Many big men born in this town?” “Nope, only little babies!”). For a few years, I drew a feature for the Saturday Evening Post “Pun-Abridged Dictionary. When my Sunday “Family Circus” page started in 1′ appended it with a weekly panel “Sideshow”, consisting of reader-contributed puns. The 25,000 letters a year that this feature drew, as well as the enthusiastic response other pun features convinced me that thi many pun-lovers in the country. (And quite few in the city, too, but they won’t admit it.)

Q: You mentioned having worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin. Is this where you started and would you fill us in on your career to date?

Q: You mentioned having worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin. Is this where you started and would you fill us in on your career to date?

KEANE: My first job was or, Philadelphia Bulletin as a messenger in the year I graduated from high school. / years in the Army where I drew for Yank, Pacific Stars & Stripes, etc., I came back to the Bulletin with a fist full of my published service cartoons. This landed me a job in the news art department drawing spot cartoons and caricatures for the entertainment section which eventually led into my syndicate feature “Channel Chuckles” in 1954. I drew magazine cartoons for most of the markets, did a weekly Sunday comic for the Bulletin called “Silly Philly” (a little Quaker character based on William Penn), and edited a 16 page weekly supplement in the Sunday paper called “Fun Book”. When the income from “Channel Chuckles” and my free stuff enabled me to leave the 9 to 5 job at the Bulletin, my wife Thel (who I had met in Australia during the war and returned down under to marry in 1948) and I, along with our five small children moved to Paradise Valley, Arizona (near Phoenix) in 1959. Working at home for the first time with our little people underfoot, I discovered that most of the magazine cartoons I was selling had to do with family life and small children. I then decided to produce a second feature for the Register and Tribune Syndicate and introduced “Family Circus” in 1960.

Q: Wasn’t it originally called “Family CIRCLE”?

KEANE: Yes. I felt the name and circle format were a perfect combination. However, Family Circle Magazine (the one you read while waiting at the checkout counter in the supermarket) objected to the use of what they claimed to be their title and forced us to change the name of the feature. Frankly, I think if my syndicate had fought a small legal battle, we could have retained the CIRCLE title. The conversion was simple: I changed the last two letters from L-E to U-S. And, many feel that the CIRCUS title is more indicative of what goes on in the cartoon.

KEANE: Yes. I felt the name and circle format were a perfect combination. However, Family Circle Magazine (the one you read while waiting at the checkout counter in the supermarket) objected to the use of what they claimed to be their title and forced us to change the name of the feature. Frankly, I think if my syndicate had fought a small legal battle, we could have retained the CIRCLE title. The conversion was simple: I changed the last two letters from L-E to U-S. And, many feel that the CIRCUS title is more indicative of what goes on in the cartoon.

Q: Would you give us a rundown on your average working day?

KEANE: On most mornings I get up about 7:30, hit the studio (which overlooks the tennis court in case somebody wants to play) about 9, and work through most of the day with a break for lunch. It seems that the creative juices flow best late in the afternoon and will continue into the evening. I occasionally work after dinner till about 10 P.M. A comfortable couch in my studio is put to good use for 20 minute naps when 1 grow weary. Some mornings, especially in the summertime, I awaken about 4:30 A.M. and work till the morning Arizona sun is drenching Camelback Mountain with yellow. I then go back to bed (about 8 A. M.) for another hour of sleep. After breakfast I return to the studio to answer mail and to the more mechanical chores of drawing. It seems that the very early morning and early evening are the best times for uninhibited creative work. Of course, this work schedule varies around our social engagements and fairly frequent tennis matches. Totally, I average about 45 hours of real work each week and love every minute of it.

Q: An interviewer once asked you if “Family Circus” was based on your real life, and you replied that, on the contrary, your real life is based on the cartoon. If a particular situation gets a laugh in the feature, you try to work it into your home the following week. Bit, is that true?

KEANE: No, but it’s a bit more amusing than the truth. My ideas are really based on our own family experiences and so are the characters. Our children aren’t as young as they once were, but, then who is? I have an excellent memory for detail and can recall vividly incidents from years ago. In fact, 1 even base a lot of the moods and childish attitudes in my cartoon on my own experiences as a small boy.

KEANE: No, but it’s a bit more amusing than the truth. My ideas are really based on our own family experiences and so are the characters. Our children aren’t as young as they once were, but, then who is? I have an excellent memory for detail and can recall vividly incidents from years ago. In fact, 1 even base a lot of the moods and childish attitudes in my cartoon on my own experiences as a small boy.

Bil and Thel review cartoons to submit.

Q: What are the ages of your five children now?

KEANE: The oldest is 25 and the youngest is 17. Glen, our 21 year old, is presently working in the animation department at Disney Productions in California.

Q: Do you get many cartoon ideas from reader mail?

KEANE: Well, not cartoon ideas per se. A young mother will occasionally write and say “Here’s something that happened in our house — maybe you can use it.” The incident she relates will form the nucleus of a situation to which I then apply my own family experience and whatever expertise I have as a gag creator. The result is usually a scene that took place in thousands of homes that very week. Basically, children never change and family life is universal and timeless.

Q: What advice would you give a young cartoonist aspiring to do a feature?

KEANE: I would highly recommend an art background. It is quicker in the long run than learning by your own mistakes. Also, stick to a subject with which you are familiar. This is the only way you will maintain high quality material. Don’t be a phony. Do what comes naturally.

Q: Obviously, since you live in Arizona, it has not been necessary for you to be close to the New York market to achieve success. Would you comment on this? KEANE: Even when I lived in Philadelphia I sold my cartoons to the Saturday Evening Post entirely through the mail and their offices were very close to the Bulletin Building where I worked. One of the beautiful things about this cartoon business is that it allows you to live anywhere there is a mailbox.

Q: How is your new cartoon book on tennis doing?

KEANE: It has only been out for a few months now, and already it’s selling into the dozens. Truthfully, the book (DEUCE AND DONTS OF TENNIS) is doing phenomenally well. Tennis is a popular subject and the $2.95 price is low enough to make it a hot item.

Q: What other books have you had published?

KEANE: Fawcett Gold Medal has published 12 paperback collections of my “Family Circus” cartoons. The newest, being released in October, is titled: “I CANT UNTIE MY SHOES!” The cover depicts Jeffy standing in a bathtub full of water. Several different publishing houses have put out books of my other cartoons. I collaborated with columnist Erma Bombeck on a book

KEANE: Fawcett Gold Medal has published 12 paperback collections of my “Family Circus” cartoons. The newest, being released in October, is titled: “I CANT UNTIE MY SHOES!” The cover depicts Jeffy standing in a bathtub full of water. Several different publishing houses have put out books of my other cartoons. I collaborated with columnist Erma Bombeck on a book

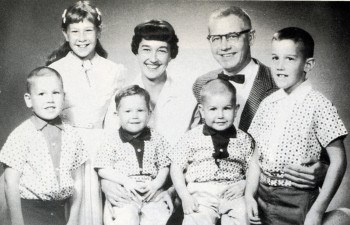

_________I believe that’s Glen to the far left._______________for Doubleday: “JUST WAIT TILL YOU HAVE CHILDREN OF YOUR OWN.” Erma is a neighbor and a genuinely funny lady.

Q: Not many cartoonists are funny on their feet as well as on paper. You have quite a reputation as a stand-up comedian delivering side-splitting talks at a microphone. Is this a natural talent or something you learned?

KEANE: It’s another thing I’ve taught myself through the years. I love to make people laugh and just eat up the immediate crowd reaction and applause, which is a pleasant change from drawing a cartoon and waiting weeks or months till after it is published for any reaction. When I give a talk, I write every word in advance. I plan the comments and one-liners carefully, making the material as topical and intimate as possible for that audience. In addition to concise, fresh material, the two important things for a stand-up comedian are delivery and timing. While giving speeches can be profitable, it is terribly time-consuming. I limit my personal appearances to only the ones I really want to do.

Q: Thanks, Bit. Do you have a final word?

KEANE: Yes — ZYZZOGETON. It’s on the last page of my dictionary. Before I close, Jud, I would like to say something nice about CARTOONIST PROfiles. I’d like to, but I can’t think of anything. Seriously, folks — your publication is an excellent chronicle of every phase of cartooning. We have all learned a lot about each other through your meticulous efforts. You deserve a big round of applause. (Jud gets a sitting ovation.) A hundred years from now people will be talking about Jud Hurd — which will give you an idea of how dull things are going to be in a hundred years.

Bill, Thel and Paradise Valley.

Articles on Animation &Commentary 22 Jul 2009 07:12 am

Recap – theories

I’d written this a couple of years ago and posted it then, but I thought I’d expand on it a bit.

I have my own, odd thoughts about animators – great, master animators – these are the only ones I’m talking about.

I think there are two types of animator. Both types, I think, are brilliant but I have my preference. Basically it’s the same breakdown I have with live action actors: the difference between Laurence Oliver and Marlon Brando. Both are geniuses, but I’d go out of my way to see one of them more than the other.

One works from the outside in, and the other works from the inside out. It’s Royal Academy vs. Stanislavsky.

Animators:

- One is a brilliant mechanic of an artist who gets every pose every gesture just right. The movement of the character is perfectly flawless, the accents are always in the right place, the timing is perfect, and the weight captured is exact.

The character is developed but usually in a manipulated, studiously planned way. Usually, this animation, to me, is cold. Give the character a fake nose, and Laurence Olivier could be playing it.

(Art Babbitt, at the top of the triangle, is to me the model for this type of animator.)

(Babbitt dwng of Mime from Hubley’s Everybody Rides the Carousel)

.

Then there is the emotional animator. The poses, gestures, actions of the character are emotionally executed by the animator as if this were the only way it could come out. The drawings are often violent and immediate – pencils ripping through paper and dark blotchy artwork.

This animator often puts emotion above mechanics, but (s)he digs to the depth of the part to find a real living thing. It isn’t always beautiful, but there’s a gem of a character on the screen. Like any living organism it’s unexpected and natural. Often this type animator works straight ahead (Does dwg#1 first, then #2,

This animator often puts emotion above mechanics, but (s)he digs to the depth of the part to find a real living thing. It isn’t always beautiful, but there’s a gem of a character on the screen. Like any living organism it’s unexpected and natural. Often this type animator works straight ahead (Does dwg#1 first, then #2,

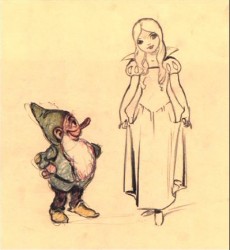

(Grim Natwick, to me, is the prime example of this type.)

No, I’m not saying if you draw dirty, rough, violent drawings you’ll be a great animator. I’m speaking somewhat metaphorically – although the two examples I gave actually did draw that way. I’m sure Art Babbitt did one or two rough,

(Grim Natwick drawing from a Mountain Dew spot.)________violent drawings in his life, but

__________________________________________________his animation feels tight, controlled, yet beautiful. Grim also did one or two clean drawings in his time – I have one, as a matter of fact, but his animation is controlled by his feelings, accumulated knowledge of craft, and emotions. It all feels immediate, spur-of-the moment. It’s alive!

I’ve only ever watched animated films with this guide going in the back of my head. Mind you, also, I have enormous respect for both of these types; it’s just that I prefer the emotional type. More than wanting my characters to think, I want them to feel.

My temptation, here, is to give the obvious list of animators and where they fall in my model, but I think for now I won’t. CGI also fits into this mold, but it’s not a great picture. I’m curious to hear what others think of this model.

- I don’t mean for this post to turn into a “praise Grim Natwick” nor a “put down Art Babbitt” statement. I hope it doesn’t read that way.

- I don’t mean for this post to turn into a “praise Grim Natwick” nor a “put down Art Babbitt” statement. I hope it doesn’t read that way.

As I’ve said in the past, I treasure the drawings I have that were done by Art. I study and love every frame of any piece he’s ever animated. I just have more fun, personally – and I underline that word, personally, reviewing Grim’s animation.

Marlon Brando wasn’t a better actor than Laurence Olivier. They just came at it from different angles, and my preference has always been the more natural side of the acting world.

Back in the late thirties when the Group Theater was formed, these actors went to Russia to search out Stanislavsky, an acting teacher who preached at the bible of natural movement – getting in touch with your inner soul to project through the acting.

Back in the late thirties when the Group Theater was formed, these actors went to Russia to search out Stanislavsky, an acting teacher who preached at the bible of natural movement – getting in touch with your inner soul to project through the acting.

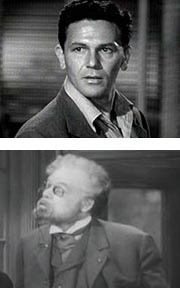

On Broadway, recently, was a revival of Awake and Sing. Clifford Odets was a member of the original Group Theater, and his plays reflected their “common man” attitude to theatrical productions. They weren’t trying to do spectacles or Royalty plays, they were trying to project the “average Joe” back from the stage. It changed theater, created Arthur Miller and a whole breed of acting styles. Compare, ex-Group Theater performer, John Garfield’s performances of the thirties with someone who was praised to the hilt back then, Paul Muni. Completely different acting styles – one natural and one overemotional and unrealistic.

The same was and is true of animators’ performances.

At Disney’s, these guys took their animation seriously. Some, such as Fred Moore and Norm Ferguson, thought they had it right and continued their own paths. Some looked into Stanislavsky and rejected it; others adopted it wholeheartedly. Still others, such as Grim Natwick, did it naturally and always had. Just as in the theater.

At Disney’s, these guys took their animation seriously. Some, such as Fred Moore and Norm Ferguson, thought they had it right and continued their own paths. Some looked into Stanislavsky and rejected it; others adopted it wholeheartedly. Still others, such as Grim Natwick, did it naturally and always had. Just as in the theater.

Next time you look at Fantasia, try just watching the acting styles. There’s nothing more Stanislavsky than Bill Tytla‘s scenes in Night On Bald Mountain, and there’s nothing less Stanislavsky than most of the animation in the Pastoral sequence.

Chuck Jones &Frame Grabs &Layout & Design 21 Jul 2009 07:13 am

McGrew’s Aristocat

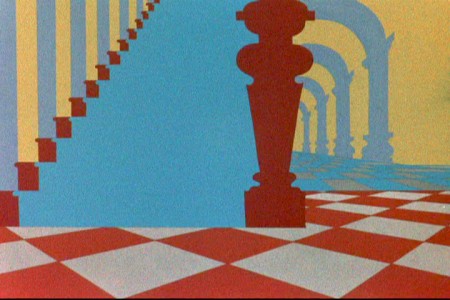

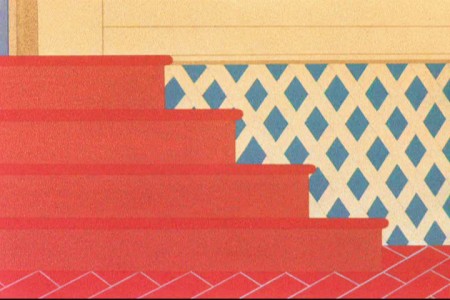

– John McGrew is certainly one of my favorite LO and Background designers in animation. His Dover Boys work in 1942 set new goals for the remainder of 20th Century animation. He followed it with the daring work of Conrad the Sailor, Inki and the Minah Bird, The Case of the Missing Hare and others all for Chuck Jones, who was no slouch, himself, in encouraging exciting innovation in design and film cutting.

– John McGrew is certainly one of my favorite LO and Background designers in animation. His Dover Boys work in 1942 set new goals for the remainder of 20th Century animation. He followed it with the daring work of Conrad the Sailor, Inki and the Minah Bird, The Case of the Missing Hare and others all for Chuck Jones, who was no slouch, himself, in encouraging exciting innovation in design and film cutting.

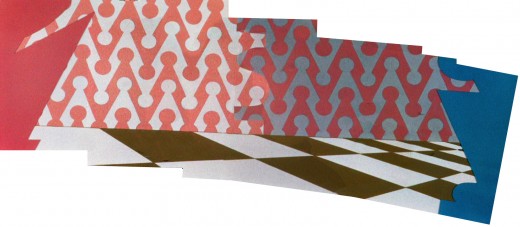

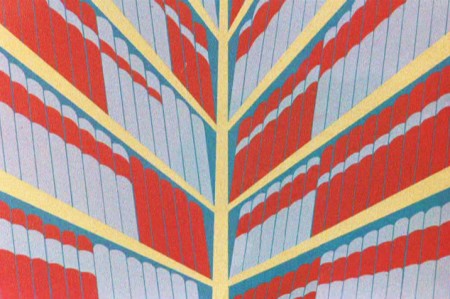

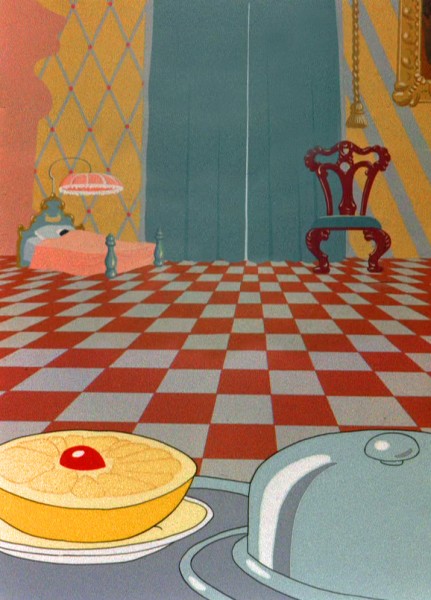

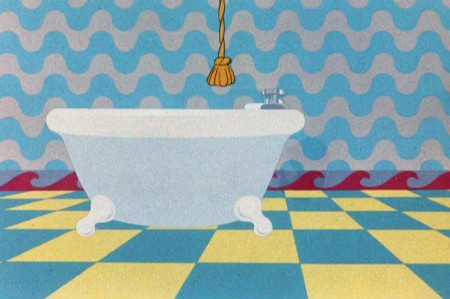

The Aristo-cat was probably the first of McGrew’s works that I saw when I was a kid. It made my eyes pop, even though I watched it originally in B&W. The dynamic design of wallpaper decoration combined with outrageous pans and camera work took me by force. The violently repeating patterns reach to the forefront of this short. All of this exuberant design completely acted to support the character’s state of mind. Anxiety, fear and terror jumped from the backgrounds to the fine character animation of Ken Harris, Rudy Larriva and Bobe Cannon.

The Aristo-cat was probably the first of McGrew’s works that I saw when I was a kid. It made my eyes pop, even though I watched it originally in B&W. The dynamic design of wallpaper decoration combined with outrageous pans and camera work took me by force. The violently repeating patterns reach to the forefront of this short. All of this exuberant design completely acted to support the character’s state of mind. Anxiety, fear and terror jumped from the backgrounds to the fine character animation of Ken Harris, Rudy Larriva and Bobe Cannon.

Working with Jones and painter Gene Fleury, he surefootedly set the way for UPA and all the others that followed. Toot Whistle Plunk & Boom and Ward Kimball’s other Disney TV work, Maurice Noble and other thinking designers of the Fifties couldn’t have broken through if McGrew hadn’t been there first supporting and pushing Chuck Jones.

Go here for Mike Barrier‘s excellent interview with him.

I’ve done some Bg recreations from the film, which meant assembling some exceptionally long pans that twist and turn. Unfortunately, I don’t think there’s a good quality copy of the film available. All of the grain in the DVD leads me to believe they copied a 16mm print.

As stills, they don’t come across as quite so daring, but they are within the moving short. It took some courage to do such work and enormous talent to be able to pull it off so successfully.

The butler walks upstairs.

He carries a breakfast tray into the bedroom.

Releasing a bar of soap to trip the butler.

Downstairs to find the butler.

The dog in the doghouse. Repeated diamonds outside.

Back indoors. Still more diamonds.

Articles on Animation &Books &Disney &Models 20 Jul 2009 07:21 am

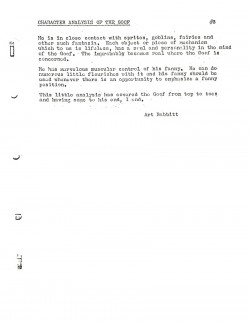

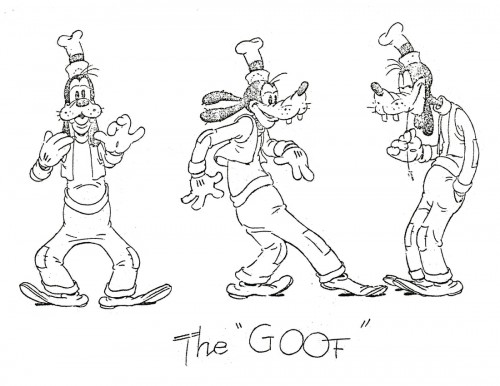

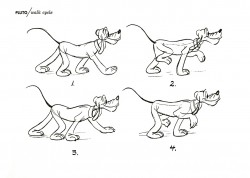

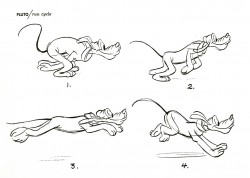

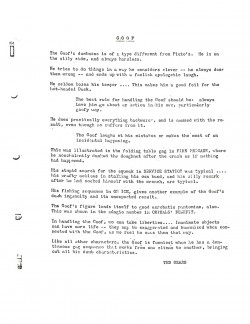

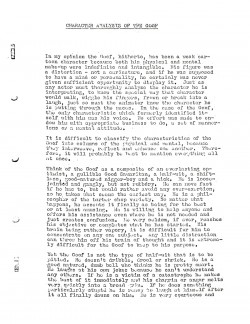

Goofy/Pluto models

- I’ve recently posted some discussions about Mickey and Donald which were part of the extrawork courses that the Disney studio held in the Thirties. Go here to see Mickey, go here to see Donald.

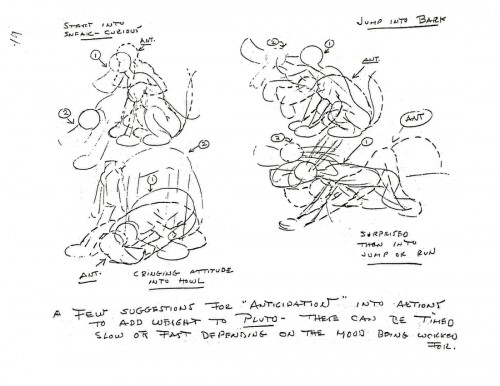

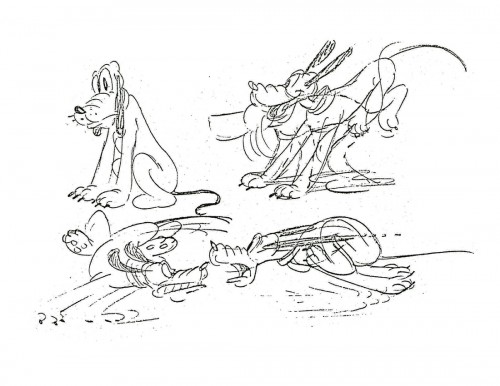

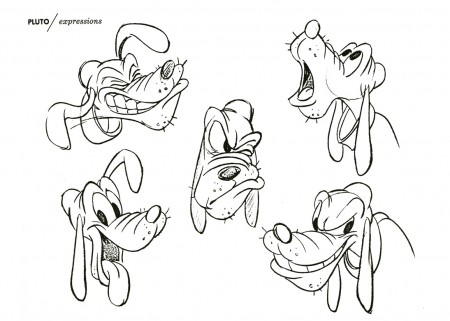

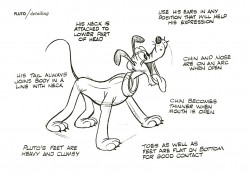

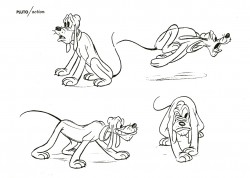

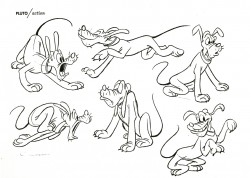

Here’s the section on the “Goof” which also includes a couple of Pluto models.

Art Babbitt is the lecturer.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge.)

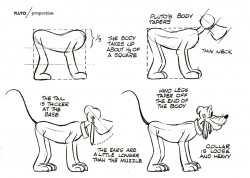

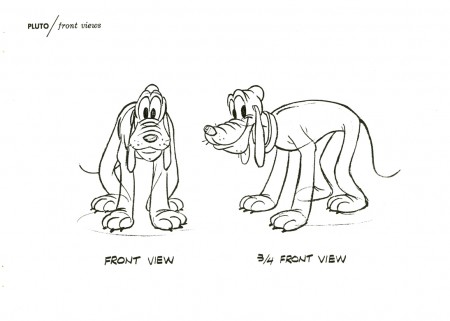

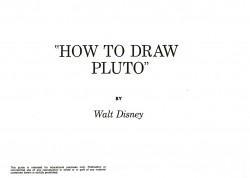

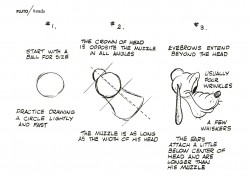

Since there were so few pages to the above document, I thought I’d add the pages of the How to Draw Pluto book which was part of the Disney Animation Kit you once could buy from the Art Corner at Disneyland. It included books on How to Draw Mickey, Donald, Goofy and Pluto as well as a book on Tips in Animation.

Here’s Pluto:

1

1  2

2

Books &Commentary &Independent Animation 19 Jul 2009 07:32 am

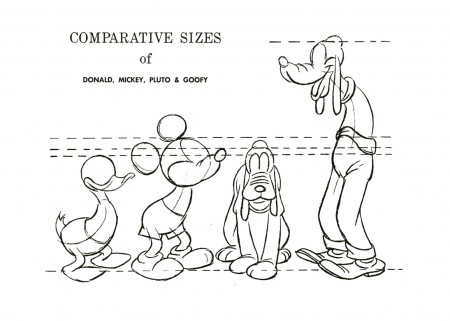

Book of Kells

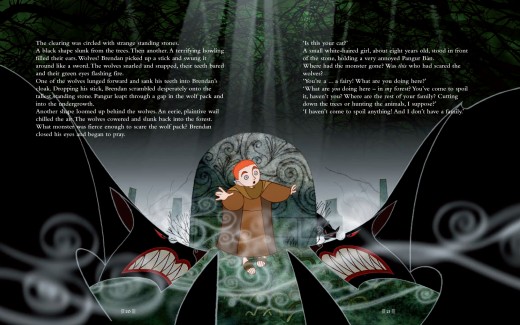

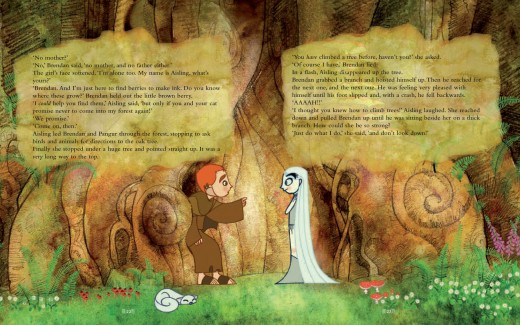

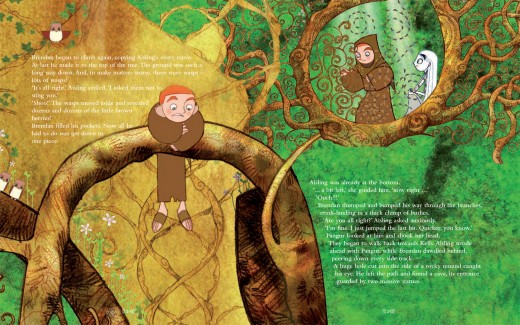

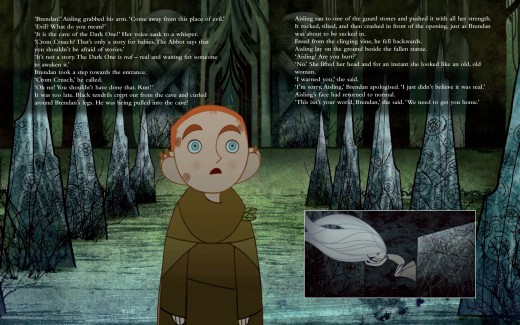

- Having seen The Secret of Kells yesterday, I felt it was time to take another look at The Book of Kells. It’s been a while for me, though the book has been sitting on my shelves for the past 35 years or so.

The artwork in the film is luxurious (although the characters tend toward the big-eyed cute side), but no matter how daring the style could have been, it didn’t quite match the absolute daring and drive of the original illustrations.

The artwork in the film is luxurious (although the characters tend toward the big-eyed cute side), but no matter how daring the style could have been, it didn’t quite match the absolute daring and drive of the original illustrations.

The Book of Kells is a hand written – drawn is actually the more appropriate word – transcription of the new testament. It was done by monks who might have spent an entire lifetime illustrating one page. The purpose was to save a written transcription of the Christ story despite the invasions of the Norse pagans.

This is essentally the story of the film, though the Christ-story part is left out. There is an  unusal mysticism within surrounding wooded areas in the film, but the mystical is left out of the Christian complex despite the fact that this is their primary mission.

unusal mysticism within surrounding wooded areas in the film, but the mystical is left out of the Christian complex despite the fact that this is their primary mission.

The most amazing part of the film is that it’s a telling of the story behind a work of Art. Of course, the monks didn’t think of it as art. To them it was just a telling of the Gospels. I’m not sure I can think of any other feature animated film that tries to relay the creation of an artwork.

I found the film beautiful, scene for scene, but felt there was, for me, no emotional connection. I might have preferred the film set in a slightly more realistic setting to separate the world of the gospels and spirituality from the real world. Others I spoke with didn’t have that reaction, so it’s no doubt my problem.

The film does feel, at times, a bit like Gennady Tarkovsky’s Samurai Jack (or, for that

matter, Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol) and is undoubtedly a virtuoso performance of flat animation. It seems to mix traditional with Flash with CGI for the end product. Some CG scenes of waves washing on the shore were beautifully constructed. Scenes of the dark, heathen woods were also beautiful.

matter, Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol) and is undoubtedly a virtuoso performance of flat animation. It seems to mix traditional with Flash with CGI for the end product. Some CG scenes of waves washing on the shore were beautifully constructed. Scenes of the dark, heathen woods were also beautiful.

However, it’s all very heavy design all the time. In fact the design seems to resolve some of the conflicts that occur in the film. At least, I wasn’t able to quite get what happened several times, except that the climaxes were waved over the abstractions of some of the scenes and everything was taken care of. It did seem to work, in a not very physical way. I’m not sure how much our predecessors, in the animation industry, would have accepted it. Not quite as satisfying as actually being able to defeat the enemies (except in an allegorical way) though even the visualization of the enemy wasn’t quite physical enough for my taste – given that so much of their art went into the Book of Kells, itself.

The film, unlike most recent animated films (Miyazaki excluded) has a sense of depth that is quite comforting to see again. I’d recommend it wholeheartedly to anyone despite my few gripes.

My guess is that it will get a larger release this year. They’ve just gained a distributor and there is that Buena Vista logo at the head of the movie. Hopefully it’ll show up at Oscar time.

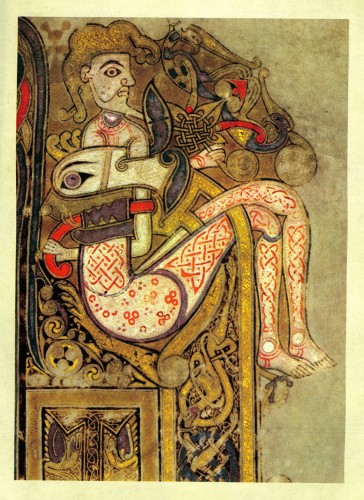

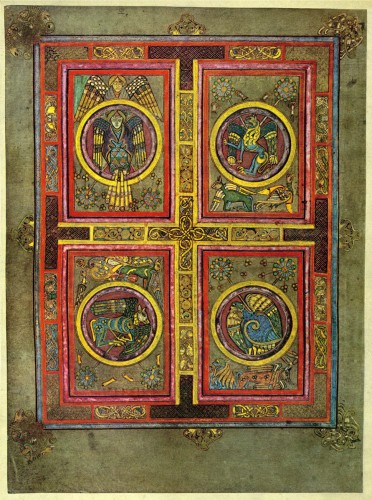

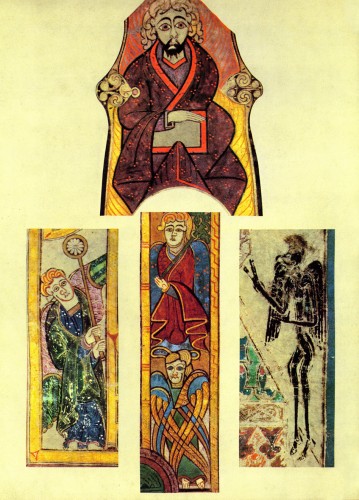

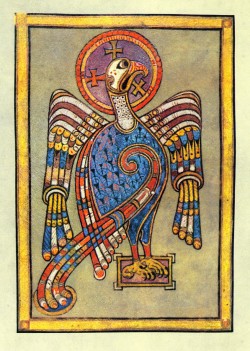

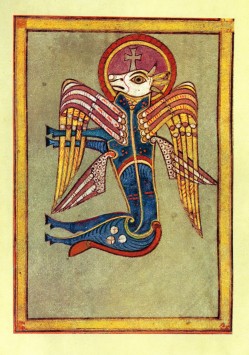

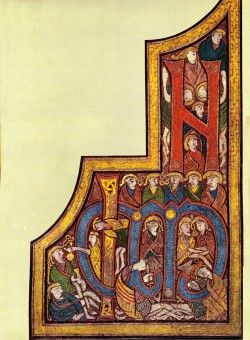

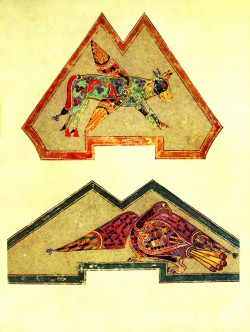

Now to some of those illustrations from The Book of Kells:

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Of course, the four Evangelists, who wrote the gospels,

are depicted throughout The Book of Kells.

A man, a lion, a calf and an eagle.

John, Luke, Mark and Matthew

The design is quite extraordinary and should have inspired

many a modern work of art.

The Evangelists, again.

Matthew and Mark.

The book, for the most part, is a written manuscript of the Gospels.

Plenty of little and beautiful iconic figures wrap around and within the

hand-drawn type.

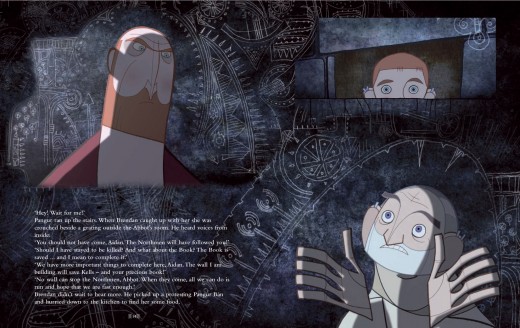

How could I resist adding this still from the film?

Books &Daily post &Independent Animation 18 Jul 2009 07:40 am

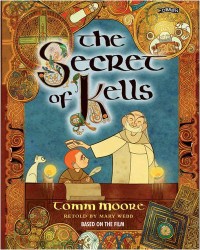

Kells

- This morning in New York, Tomm Moore’s The Secret of Kells will be playing the first of two shows at the IFC Center. The second show is tomorrow, Sunday, at 11am. (Reserve a ticket for that show here.) I intend to be at the screening this morning and maybe later in the day I’ll add some comments to this post about my thoughts on the film. I’m hoping it’ll be good, though I have to admit that I have some trepidations with the character design. A bit too cute for my taste, but I can’t judge until I properly see the film. The overall production design looks impressive.

- This morning in New York, Tomm Moore’s The Secret of Kells will be playing the first of two shows at the IFC Center. The second show is tomorrow, Sunday, at 11am. (Reserve a ticket for that show here.) I intend to be at the screening this morning and maybe later in the day I’ll add some comments to this post about my thoughts on the film. I’m hoping it’ll be good, though I have to admit that I have some trepidations with the character design. A bit too cute for my taste, but I can’t judge until I properly see the film. The overall production design looks impressive.

You can read the NYTimes review here. They’ve given the task to a second-string reviewer and treat it as a children’s film despite how positive the review is. At least the paper gave it some attention.

For now, I’ve noticed that a picture book of the film is available. On the site, they’ve given a couple of the double page spreads to check out. I’ve copied them below to give you an idea of this book, which looks as impressive as the film.

The book sells at this site for £12.99 (about $25.00); the same book on Amazon is selling for $125.00. They’ve also posted the trailer for the film at the book’s site, so it’s worth a visit.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 17 Jul 2009 07:40 am

Bob Godfrey Interview

Here’s an interview with Bob Godfrey by John Cannon pulled from Animafilm 2/1979.

John Cannon: What do you think of animation as a specific category of film art? What are its capabilities and limitations?

Bob Godfrey: My answers to it vary with the kind of mood I’m in. It is a very small part of film art and has tremendous capabilities and many, many limitations. One of the reasons for the present state of the industry is that we are not enough aware of the limitations of the medium that we are in. There are lots of things that animation cannot do or shouldn’t do and we seem to be doing them.

Bob Godfrey: My answers to it vary with the kind of mood I’m in. It is a very small part of film art and has tremendous capabilities and many, many limitations. One of the reasons for the present state of the industry is that we are not enough aware of the limitations of the medium that we are in. There are lots of things that animation cannot do or shouldn’t do and we seem to be doing them.

JC: Such as?

BG: The things that live-action handles terribly well like Ingmar Bergman, … personal relationships. In fact live-action is moving into areas that should really be our areas like “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” or “Star Wars”. Animated film should go into the impossible, the fantastic, into the mind of man, because the live-action camera has been literally everywhere it can ___________Bob Godfrey

go on earth — it’s even been to the moon. It’s getting

extremely difficult to amaze people. What cinema has to be into is.

FANTASY AND SPECTACLE. To do spectacular things in animation on a big screen costs a lot of money, a high risk with the decline of the short film, which I lament terribly – the short film is slowly being strangulated by the people who run our business, the distributors. There are no short films exhibited in the principal market, the United States, and very few short films shown here. There’s the old adage “if you want to lose money make a short” and that dies hard in Wardour Street. You can’t get the money to make shorts. Nobody goes to the cinema to see a short – they go to see a long.

So we as animation producers are being forced (if not forced some of us are going willingly) into one of two areas; television with commercials of forced into making longer films, the long feature-length animated film. One has to think very long and very hard before venturing into this area. Judging by the films I’ve heard about or seen recently we are not coming up with the ‘smash hits’ and unless you’re a smash hit your’re nothing; there’s no longer a place for a B feature. We’re not coming up with the ‘smashes’.

So we as animation producers are being forced (if not forced some of us are going willingly) into one of two areas; television with commercials of forced into making longer films, the long feature-length animated film. One has to think very long and very hard before venturing into this area. Judging by the films I’ve heard about or seen recently we are not coming up with the ‘smash hits’ and unless you’re a smash hit your’re nothing; there’s no longer a place for a B feature. We’re not coming up with the ‘smashes’.

JC: Why not?

BG: Wrong subjects perhaps. Perhaps it should be for the children’s market here. Children are catered for by Walt Disney but I don’t know many other children’s producers. I want to make a children’s musical because I think it’s a good idea, because when you’ve outgrown one audience, in another seven years there’s another coming along.

I don’t say that animation should cater solely for children of the family audience. Look at the work of Ralph Bakshi – he works for the young teenage market, the biggest audience we have, the young people who don’t want to sit at home at night.

There’s been a whole spate of animated films recently from the West Coast of America and I don’t think any one of them has really been the

‘smash’. It shouldn’t be to difficult – at least we’ve got to do something to our audience: if we can’t amaze them, perhaps we can still make them laugh, make them cry. You must engage your audience’s emotions and possibly animation is failing in this.

THE ENTREPRENEURS. In animation tend to be the artists — artists in the sense of an artistic background – and perhaps these aren’t the right people to communicate with audiences. One must be a showman first and an artist second, like Disney. He had the great faculty for giving people what they wanted, whereas today there seems the great tendency for self-indulgence on the part of animation producers. It’s what they want first and what the public wants second. It’s a strong temptation for anybody working in animation.

JC: Can animation still hold the audience? BG: Yes, more than anything. We’re just wasting the medium – a sameness is coming over. There’s a tremendous desire to do a quality product after all the conveyor-belt type stuff we’ve had over the last few years.

There’s reaction against that and a strong desire here in London and the West Coast of America to do the quality product. Against that there is the lack of mone’y, the sheer cost of producing an animated film. We’re exploring ways – that’s what “Great” was, an economical way of doing something at the same time as keeping it moving and keeping it entertaining. In these respects it’s successful – it only cost ‘£ 36,00 to make, not a lot for a half-hour animated musical.

It’s good to continue with the musical but we need good stories… maybe animation’ought to be yanked out of art schools and put into drama schools. That would be a start. There are far too m%y artistic considerations and not enough dramatic or story-structure considerations, that is the trouble. We must rethink plus the fact we have no tradition to fall back on.

JC: Has there been no tradition at all? Where do you place the old ‘classics’ of America animation?

BG: The Disney films and Fleischer films came out of the short tradition. The animation house on the side of the big American distributors.

JC: They all had to have a house cartoon?

BG: Yes, Warners, UA and that sorl Everyone on the side of the live-action Out of this came the “Silly Symphonies the longer things. Disney is the only one his place with long animation films. Af Disney moved to live-action which si way he was going anyway; he moved “Jungle Book” which was terrific for me. There was another lull after his death and suddenly came up with “Yellow Submarine.”

BG: Yes, Warners, UA and that sorl Everyone on the side of the live-action Out of this came the “Silly Symphonies the longer things. Disney is the only one his place with long animation films. Af Disney moved to live-action which si way he was going anyway; he moved “Jungle Book” which was terrific for me. There was another lull after his death and suddenly came up with “Yellow Submarine.”

JC: Which was a shot out of the blue?

BG: I don’t think it changed anything at all. It was certainly a milestone. We talk about before “Yellow Submarine” and after “Yellow Submarine”.

A very important and good film but somehow synonymous with swinging London, the Beatles, 1967, 1968 and now it doesn’t seem to matter so much, it’s history. It changed nothing because we all suddenly went back to making things that came before it.

BAKSHI’S HAPPENED – a phenomenon. He has tremendous energy and makes more features than dogs have fleas. He does a great amount of work. He’s now doing “The Lord of the Rings.” All he does is interesting. He’s a fantastic foree in our world, extremely good for the industry. We rush to see his latest films here. He’s taken animation out of the slightly infantile area of pigs in sailor hats and animated nursery-rhymes. He’s made it into the urban nightmare… Look at the New York of “Hoppity Comes to Town” and compare it with, say, “Heavy Traffic” and there’s great sociological comment there. It reveals what has happened to a city in thirty years and what has happened to attitudes. Bakshi has brought animation up to date and one must admire him for that. He’s not had a ‘smash’ yet but I hear amazing stories of “The Lord of the Rings” and it being Bakshi whatever I hear, I believe. He’s the saviour of the West Coast. Box-office success it what it’s all about.

JC: Could critics help animation?

BG: You have drama critics, ballet critics, opera critics. You don’t really have animation critics. This is a great pity. I never see an animated film really criticized properly.

JC: Who could do that?

BG: Someone who knows something about animation. We work in a subject there’s a lot of ignorance about. It’s always handled by the run-of-the-mill film critic. We need an Apollinaire, someone to write about us from the inside, perhaps a failed animator turned journalist… We do need some penetrating analysis right now. Animation, because of animation festivals, is terribly incestuous. At festivals – the only place we meet nowadays — we’re

PREACHING TO THE CONVERTED and in a way the pressures on animation have reduced it to the sort of sameness. The days of the house-style of a few years ago have gone. There’s kind of faceless uniformity about it now.

The advertisers have forced their styles onto us here whereas in the past they had to have our style or leave it. There is still a Disney style, they’re the only ones who can afford it and they don’t make commercials.

JC: Haven’t commercials been of positive use beyond keeping some animators is business? BG: It’s a two-edged sword. On balance it has done more harm than good. Well, they’ve kept us alive. We have to look for alternatives although there are studios completely dedicated to producing animation for commercials who would not want to do anything else.

Halas and Bachelor try to get away. I probably do more entertainment than anyone else in Britain. Richard Williams has his films, “Raggety Ann and Andy”. He built up the Pink Panther tradition too when it was fashionable to have expensive titles. In “Charge of the Light Brigade” the animation said it all, I don’t know why we needed the live action! But financial recession has slammed the door of artistic titles in our faces.

All images are from Godfrey’s film, GREAT.

JC: What doors are opening?

BG: Well, the National Script Development Fund have given me money to work out a package to do an animated feature. I have made a couple of successful animated shorts that prove that you can make money out of them, but I don’t want to keep on trying to prove it. It’s too exhausting.

Having proved it, I’m doing one last short with Vladko Grgic in Yougoslavia which I think will possibly be the best short I’ve been associated with. I’d like to take a

HOLIDAY FROM SHORTS. I’ve done more than most people – and get into the longs. I feel I’m equipped to do it because of the two series which were the equivalent of four hours of animation, a hell of a lot. I’m venturing now into a new area for me. I hope I don’t catch a cold.

One must now think internationally. The film “Jumbo” is set in England and New York so this gives it the transatlantic appeal. The trouble with “Great” was it was so English; no-one understood it.

JC: But it won an Oscar?

BG: It won an Oscar but it’s never been distributed in the States; they’ve never heard of Brunei and they’ve only just heard of Queen Victoria. I blame the distribution system. It’s no good making an animated film unless you have good links with a distributor. JC: But,,Great” was fortunate in Britain? BG: It was fortunate in that it was commissioned by British Lion who subsequently went bankrupt… not solely because of “Great”! You must have the guarantee of distribution before you start anything.

JC: What is it like working in Britain now?

BG:. It’s a bit like Dickens, a best of times and a worst of times. It’s amazing now we keep going. One reason it that British animators are among the best in the world – I say that not to bang the drum or rattle the sabre — I believe that. “Yellow Submarine” helped to bring on a generation of, talented animators, mostly spread out in little tiny companies. I’d hate to see them go down because of escalating costs, rents, etc…

IT’S A TERRIBLE STRUGGLE we have to go on, for some there’s nothing else. We’re attracting more work from abroad – France and Germany. I’m working on “Sesame Street” for Kuwait, Nigeria. Africa is opening up – one door shuts, another door opens. I have to keep my ear to the ground and move with the times. The markets and patterns change all the time, but we are still keyed to the side of the advertising industry.

JC: How should animation be taught?

BG: I teach in an art school one day a week and I am anti-art school and pro-drama school. We must avoid the artistic self-indulgent area. I’m guilty of this too because I financed the films myself and why the hell shouldn’t I?

The cult of the director is something out of Europe — not America where one had the great commercial directors who until recently no-one had ever heard of. In the 1960′s they were re-discovered and the French began saying isn’t Howard Hawks marvellous, which of course he was, or Ford, or Wyler. Nobody said the films were great because they directed them. It was out of Europe that we got the ‘artistic’ film and the cult of the director which has been shipped in animation over to Canada which rarely makes it into the commercial cinema.

JC: Are the new technologies offering any new opportunities for animation?

BG: You mean the great video-tape breakthroughs that are always going to happen? The computer animation that will take over the world? It never happens. Basically it is produced now as BY FLEISCHER ALL THOSE YEARS AGO, equipment’s a lot better and we’re standardizing more. There are more and more animation rostrums in London. Let’s hope they all keep busy.

JC: What about animation and television?

BG: Animation goes into television through commercials and is well paid but animation for programmes is poorly paid and consequently we’re not doing well there. The “Muppets” work — they’ve effected the compromise between instant live action and the sheer labour of animation which makes it impracticable for instant television. Television is instant; animation isn’t. Perhaps the demarcations are natural.

Animation belongs in the cinema where we can afford to labour longer and spend more – for television we can’t produce it fast enough or economically enough.

I’ve never liked puppets very much — I’m not exactly a puppetteer – I love Trnka puppets and Pojar but it doesn’t seem to belong in this country; rather in Poland, Russia, Czechoslovakia where there are such marvellous tradition of puppet work. The “Muppets” however, who grew out of “Sesame Street” are superb, really funny. The “Sesame Street” tradition has helped get work on the small screen. I don’t know how we can solve

the major problem though of the very badly paid area of animation for television programmes. That’s why most of the animation on television is of so low a standard, but what can anyone do with a microscopic budget?

JC: We’ve talked of financial limitations a great deal. What of the other limitations?

BG: Animation is still the art of the impossible; it should concern itself with this but so has live action recently. “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” does this and this is what makes it so mind-boggling. It wouldn’t have been believable as animation as it would lose credibility.

People see animation and do not find it offensive. “It’s a doll” or “it’s a cartoon”. We can make dogs talk. We should deal in imaginative situations. My students don’t really think cartoon. They think live-action and you’ve got to really work on them to think like a cartoonist. A lot of students will have a hand come on the screen and move something. I ask “why the hand?”; it’s simple, acceptable cinematic trick to make the thing move by magic. You must condition yourself to the world of Melies, he was so wonderful because he did tricks.

JC: But your persona is not so much a trickster on screen but an everyday ordinary bloke?

BG: Oh, the Stan Hayward/Bob Godfrey syndrome. Yes, he’s your everyday standard man, with a blown mind. His fantasies are extra-ordinary and this is what I’m doing now. My elephant is ordinary – well he’s not ordinary, he’s the biggest elephant in the world – but his fantasies are amazing. It’s the coming together of the fantasy world and the real world. A mad person cannot differentiate between the two; the two worlds merge. But some people, like “Henry 9 Till 5″ keep fantasy in one compartment and reality in another. I like working with Stan Hayward: he’s one of the few people who’s bothered to sit down and think what animation is all about.

JC: How do animators benefit from film festivals?

BG: The thing about festivals is to realise the background against which those films are produced. How difficult it is for Bruno Bozzetto in Italy? What are the difficulties in Czechoslovakia, Moscow, Yugoslavia? You and I are going to Poland so we’ll find out what things are like there. How do animators function UNDER STATE SUBSIDY? There’s a lot more corning here insofar as a lot of the work I do now is short information films for the Central Office of Information. Does the Canadian Film Board work? – yes, because we get wonderful animators like Caroline Leaf. Without the Film Board a woman like Caroline would not get the opportunity to come through and carry on her experiments. There’s nothing like it anywhere else.

In Britain we’ve got the National Film School now which is supposed to be working well and the London International Film School and the arts schools and colleges. A lot of the people working in London are old student of mine from Farnham and Guildford and are moving in. I suppose one person in three gets fixed up in the industry from school. One minute everybody is working, then the film finishes, and everyone is out of work and a great nebulous mass of people move round trying to get absorbed on other things – like musicians here moving form gig to gig, band to band.

JC: Can you tell us something about your new project, “Jumbo”?

BG: It’s a pilot. If I hadn’t done “Great” I wouldn’t be doing “Jumbo”. HE WAS A BIG ELEPHANT, who was around in the nineteenth century. I don’t make films about the nineteenth century through choice. I seem to get lumbered with them. Other people might say I’ve got a size fixation; the smallest man in the world making the biggest ship in the world and now the biggest elephant in the world.

I read Professor Bill Jolly’s book, bought the film rights and applied to the National Script Development Fund and was very lucky and got allocated the money last August. I’m now trying to get the pilot together. I think you always start by trying to make the film the same way as the one you’ve just finished , so I tried to get the old team off “Great” together again, some times with success. With my films there is a sort of continuity. I always start off with making the last one all over again and somewhere through it changes — thank God it changes, otherwise I’d be making the same film through all over again!

“Great” was made in an incredibly disorganised way because it was the first long film I’d ever made. I have to be organised now because we’re only paid to develop the script. So, for my £10,000, I have to produce a story-board, ten to fifteen musical numbers and lyrics and a screenplay. I’m story-boarding with one of my great artists Anne Jolliffe; music is being done by Johnnie Johnson; Colin Pearson who did the lyrics for “Great” is doing the lyrics. It’s a little bit of the old team but learning from our mistakes in the last one.

It’ll run for seventy-five minutes. We’ve got this awful, almost surrealist fact that the elephant got run over by a train and although I’ve been advised to leave it out as it might disturb children I can’t. I’m haunted by this poor beast’s death and I’ve got to put it into the story whether it kills me at the box-office or not. To me why Jumbo is immortal and famous is not because he was big but because he was run over by the train. I’ve tried to make it as funny as I can and have shifted it up to the front of the film. Death can be humorous, it doesn’t have to be incredibly tragic. One of the great twentieth century phobias is death. We’ve had the sexual hang-up and luckily we’re talking or screwing our way out of that one. Death? Why not? Stan Hayward’s making funny films about death and kids go “bang, bang, you’re dead” all the time. If we keep it at that superficial level and at the front of the film so that the kids don’t get too attached to the elephant I think we’ll get away with it.

It is important Jumbo dies. Brunei dies. I seem to be getting stuck with people who die at the high point of the film. Jumbo gave his name to the dictionary, he is synonymous with everything big, enormous, large and wonderful, It’s the story of a simple, everyday, neighbourly elephant who becomes a star, a world-beater, a blockbuster if you like.

I’m at the story-board stage now. I have a love-hate relationship with this stage of a film, it’s the most difficult part of the film after the story – the rest is just shovelling coal. It’s hard work but THE IDEA MAKES THE STORY and this underlines all I’ve been saying in the interview. If the story’s not right you can do all the most brilliant animation in the world and it’s not going to work. The idea must be right.

by John Cannon

Articles on Animation 16 Jul 2009 07:25 am

House of Brick

- I found this short piece by E.B.White in a 1933 edition of The New Yorker magazine, and thought you’d find it amusing.

- I found this short piece by E.B.White in a 1933 edition of The New Yorker magazine, and thought you’d find it amusing.

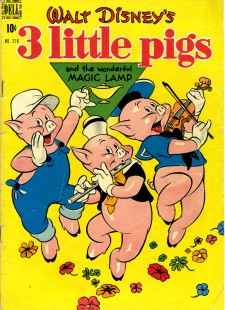

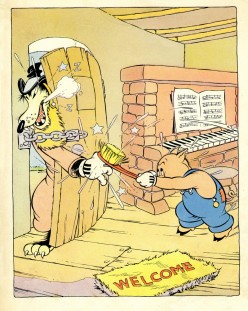

- House of Brick

WALT DISNEY raised his own salary from $150 a week to $200 a week, as a reward for having produced “Three-Little Pigs.” We got that from his brother, Roy Disney, who was in town last week. Roy manages the Walt Disney interests, and is full of figures about the pigs. They, the pigs, have been shown at 400 theatres in New York City alone, far a total run of 1,200 weeks. They ran for eight weeks at the Trans-Lux Broadway theatre, the only picture that was ever shown there for more than one week. It, or they, flashed on the screen one hundred times a week, and about 250,000 people cheered the opus at that one theatre alone. Out of town, the pigs were just as much of a smash, and Walt has received countless requests for further adventures. He doesn’t think he’ll make a series, though: thinks the chances are against his being able to repeat.

The Music Hall gets the credit for having first shown “Three Little Pigs” here, the week of May 25th to 31st, 1933, Pinto Colvieg, (sic) a former newspaperman now working for Disney, gets the credit for the line “Who’s afraid of the big had wolf?” The song was published in September by Irving Berlin and in two weeks had become the second national best-seller, being topped only by “The Last Round-Up.” The Disney staff are just a bit sheep-faced about the pigs, because when Walt suggested the idea, in September, 1932, none of the directors reacted. It seems that, the Disney procedure is, Walt proposes but a director disposes. Not getting any reaction, Walt shelved the pigs. They kept coming up in his mind, though, and he suggested them a second time. Again no reaction. The third time, the reaction came and the pigs went into production.

The Music Hall gets the credit for having first shown “Three Little Pigs” here, the week of May 25th to 31st, 1933, Pinto Colvieg, (sic) a former newspaperman now working for Disney, gets the credit for the line “Who’s afraid of the big had wolf?” The song was published in September by Irving Berlin and in two weeks had become the second national best-seller, being topped only by “The Last Round-Up.” The Disney staff are just a bit sheep-faced about the pigs, because when Walt suggested the idea, in September, 1932, none of the directors reacted. It seems that, the Disney procedure is, Walt proposes but a director disposes. Not getting any reaction, Walt shelved the pigs. They kept coming up in his mind, though, and he suggested them a second time. Again no reaction. The third time, the reaction came and the pigs went into production.

A Mr. Frank Churchill, one of Disney’s 140 employees, took five minutes off and wrote the chorus of the wolf song, It is the first song hit ever to come out of an animated-cartoon studio (and incidentally it always seemed to us to come out of “Die Fledermaus”). Originally the words appeared like this: “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf, big bad wolf. big bad wolf? Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf? He don’t know from nothin’.” The last line didn’t seem to fit, somehow, and the staff men convened and tried to find a word that rhymed with “wolf,” They huffed and they puffed, but they finally gave up and had the two pigs who sing the song play the last line on their flute and violin.’

Colvieg (sic) was called upon to speak the part of the wolf, and he also did the pig in overalls. Girls from a trio called the Rhythmettes, Hollywood talent, sang for the two jerry-builders. The cost of making a Silly Symphony runs from $18,000 to $30,000; and the pigs were by no means the most expensive to make. Most Sillies gross between $80,000 and $100,000 over a three-year period; “Three Little Pigs,” Roy told us, would probably triple that amount. Walt makes thirteen Mickeys and thirteen Sillies a year. All the profits go back into the business. Two new Sillies are all ready to he sprung: “The China Shop,” to be released in the next couple of weeks, and “The Might Before Christmas,” at Yuletide. The pigs are soon going into the French and the Spanish. We’ll try and get you the words.

Colvieg (sic) was called upon to speak the part of the wolf, and he also did the pig in overalls. Girls from a trio called the Rhythmettes, Hollywood talent, sang for the two jerry-builders. The cost of making a Silly Symphony runs from $18,000 to $30,000; and the pigs were by no means the most expensive to make. Most Sillies gross between $80,000 and $100,000 over a three-year period; “Three Little Pigs,” Roy told us, would probably triple that amount. Walt makes thirteen Mickeys and thirteen Sillies a year. All the profits go back into the business. Two new Sillies are all ready to he sprung: “The China Shop,” to be released in the next couple of weeks, and “The Might Before Christmas,” at Yuletide. The pigs are soon going into the French and the Spanish. We’ll try and get you the words.

The above recapitulation serves to remind us of a grotesque moment in the lobby of the Music Hall when we asked a tall, elaborately uniformed man what time the “Three Little Pigs” would go on. “I assure you I haven’t the remotest idea,” he snapped. This answer didn’t have the familiar Roxy note, and we looked up and saw that the man was a West Point cadet. You got to watch yourself.

And now for something completely different:

Today’s NYTimes includes an article about a short film, Live Music, that was done via the internet utilizing volunteers through a facebook situation. Each volunteer was offered $500 for the finished scene. Sony will distribute the short with their upcoming animated feature, Planet 51.

The article goes on to say that they would like to do a feature film this way. “I certainly see this as a step in the democratization of creative storytelling in Hollywood,†said Yair Landau, the producer of the film.

What we have here is further proof that character animation is dead. Picking up one scene from a film, that you are in no other way connected to, does not give one the opportunity of doing ANYTHING in the way of proper character animation or development. The only profitable thing about this type of filmmaking is that the producer will be making money off the backs of those volunteering to animate for him. He might as easily send the work to India or China (except that there’s a better likelihood that the professionals over there would be able to add a twitch of character animation.) The animation industry seems to have built it’s house of straw.

Animation Artifacts &Disney 15 Jul 2009 07:21 am

Walt-Graham communique

- By 1935, Walt Disney had realized where he had to take his studio. Principal to the plans he had was the education of the artists within his studio.

- By 1935, Walt Disney had realized where he had to take his studio. Principal to the plans he had was the education of the artists within his studio.

At this time, a number of students were wending their way from Chouinard Art Institute to the Disney employ. In 1935, there was a large gathering of teachers from Chouinard who came to the Disney Studio one evening to see the environment and start to mold a union between the school and the studio. Disney offered a catered meal for the event.

The studio became permanently linked with Chouinard, which eventually became Cal Arts. Disney stayed in close contact with a number of instructors and selected an obvious choice for the large task of helping to educate those within his studio. _____________________Don Graham

He planned a night course several days a week in which Don Graham would lead and he would involve a number of key designers and animators in instructing within the studio.

Prior to the start of classes, Disney wrote a long letter to Graham to discuss what he hoped would be taught. Here’s that letter:

1

1  2

2