Independent Animation 14 Jun 2011 06:36 am

George Griffin – Filmmaker

- George Griffin has been something of an inspiration to me. His films have colored my view of what an independent artist can do with animation, and made me feel that it was possible for me to go forward with some of the films I’ve done.

- George Griffin has been something of an inspiration to me. His films have colored my view of what an independent artist can do with animation, and made me feel that it was possible for me to go forward with some of the films I’ve done.

His earlier films had the process of animation and filmmaking technique as a sub-theme and, in many ways, glued them all together as coming from the same personality. This sub-theme was very close to my heart, and I bought 16mm prints of several of George’s films a number of years ago. Consequently, I’ve seen Head and Viewmaster many dozens of time. I’ve certainly never tired of watching them.

When approaching the idea of highlighting the work of some of the Independent animators around the world, it was natural for me to approach George first. He’s a concerned artist whose work has helped drive me forward.

I’d sent George a few questions which he so graciously answered, and I’m posting his response here as the substance of this article. I found inspiration even in reading the response and have spent some time this morning, as a result, looking over some of my more personal projects. I hope it does much the same for you.

Q. Can you give us an idea of your beginnings? Where you went to school and why you went into animation.

Drawing came first, as with every child, before writing, and with encouragement from my parents (father was an architect) and pals. I drew and absorbed cartoons as a truant, instead of studying at school or at home. My parents forbade comic books because they thought they were limiting and vulgar, so I had to sneak off to read them. Ditto TV. There was little help from schools, either; I couldn’t deal with criticism from authority figures, especially art teachers. I was also captivated by photography and what was called hi-fi (building electronic components from a kit), machines that involved sound and image. I learned darkroom photography skills in the Army (drafted pre-Vietnam, after dropping out of college); designed posters, then learned silkscreen and type setting in order to print them; finally graduated college in political science and came to NYC to “find myself.†So, basically, false starts, no real art schooling, learn-as-you-go.

When I came to NYC I first worked in government for Head Start but the city had a way of fracturing all the walls and boxes I had constructed throughout my life. I went to films constantly, hung around NYU film school where my friends were enrolled. When I showed my drawings to anyone, I simply splayed them out on a table where people could just dig in and choose what they wanted to see. This made me a little impatient. I wanted to control HOW they looked at the drawings. That was the epiphany. I had already seen Breer, Brakhage and Vanderbeek, (also Godard) so I bought a used Bolex and tried to teach myself how to animate. Stop-motion, was easy but cartoons were another matter. I had to go to school.

,

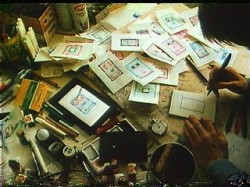

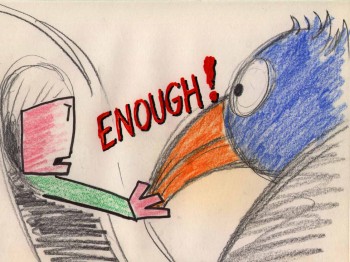

Two stills from “Head” (1975)

Q. I know that some of your first work with animation was studio driven. What moved you to get away from that commercially driven form and more toward the art form?

The work-flow at Focus Design, typical for the period, involved many specialists. It was well known for its use of designers like Rowland Wilson and Tomi Ungerer, but the real storyman was our director, Phil Kimmelman, who created pitch-perfect boards in a generic style that expertly framed the 30 second narrative. Bill Peckmann, a virtuoso stylist, did layout and design, no matter how precise or loose the style. (of course it is Bill who now supplies much of the wonderful, vintage graphics for Michael’s blog).

Yellow Submarine had just come out (I had particularly loved “Lucy in Sky”). Most of the older artists at the studio were grouchy because it was a “designer’s†film, not an “animator’s†film. Then I was laid off when business slowed. I had already become frustrated by the division of labor and had lost interest in drafting and timing skills and continued to experiment at night.

Yellow Submarine had just come out (I had particularly loved “Lucy in Sky”). Most of the older artists at the studio were grouchy because it was a “designer’s†film, not an “animator’s†film. Then I was laid off when business slowed. I had already become frustrated by the division of labor and had lost interest in drafting and timing skills and continued to experiment at night.

_______________

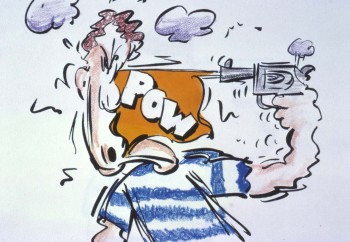

Being in the u-nion helped to ____________________“Flying Fur” (1981)

get free-lance jobs as an assistant,

most memorably a one month stint as an assistant on Fritz the Cat working under legendary animators Jim Tyer, Marty Taras, and Johnny Gentillela. I was fired by Ralph for not knowing how to clean Tyer’s amazing, scribbly extremes. Maybe it was the authority issue again. My wife now speculates that my “cats per hour†speed was too slow.

Concurrently I was able to produce small graphic jobs on my home-made stand. Then I got a 15 second Sesame Street spot based on one of five boards I had submitted. By 1969, I had begun to make my own films. So by the early 70s I had developed a bifurcated view of the art: professional, slick, commercial, studio-produced work for hire on the one hand and experimental, personal work done independently, without a budget, as an amateur (i.e. for love). This almost dialectical split seemed to demand an existential choice and I became a kind of evangelist for fusing design and animation in one stroke, but in fact I kept a foot in both camps. So, in the end, the lessons learned at Focus helped me later to earn a living.

,

Q. Your earlier films (HEAD, VIEWMASTER, even in a way FLYING FUR) seem to have a goal of exploring as well as exploiting the history and medium of animation & film as well as telling each surface story within the film. Yet, at some point, this theme appears to have left the more recent films (A LITTLE ROUTINE, KO KO, NEW FANGLED) wherein the narrative element comes more to the surface. Was there something that caused that change?

One way to consider the films is to mark a transition from self-conscious, reflexive experiments to work that’s narrative-driven, more accessible, more thematic, in a way more personal. You could say “New Fangled†is about advertising jargon, even though the linkage is obtuse, with double meanings and mysterious references. I was doing a lot of commercials at the time so it was a bit like biting the hand _________________ “New Fangled” (1992)

One way to consider the films is to mark a transition from self-conscious, reflexive experiments to work that’s narrative-driven, more accessible, more thematic, in a way more personal. You could say “New Fangled†is about advertising jargon, even though the linkage is obtuse, with double meanings and mysterious references. I was doing a lot of commercials at the time so it was a bit like biting the hand _________________ “New Fangled” (1992)

that fed me. Also, “A Little Routineâ€,

with my daughter and I as characters (a homage to the Hubleys), clearly embodies a big change in my personal life, dealing with emotional issues and sentiments in ways that would have been impossible during the “anti-cartoon†period of the 70s when I was quite focused on process and animation as a kind of language. Both “Flying Fur†(based on Scott Bradley’s brilliant score for a Tom and Jerry) and “Ko-Ko†(Charlie Parker’s famous tune) are driven by the music track, the former being an unscripted, spontaneous cartoon drawn in one month, the later an improvised abstraction performed with bits of torn paper and dried beans; both are two sides of the same coin. But I’m not so sure I understand the shifts underlying these changes. Even now they appear fluid, with reflexive elements popping up in the later work, documentary elements and stylistic discontinuities throughout. I try to understand the deeper implications of individual films, but not the overall arc of the work.

“Viewmaster” 1976″

Q. Does working with computer technology as opposed to the camera have any effect on the themes of your films? What programs do your prefer working in to create your animation? Any thoughts about 3d/cgi?

Changing from cameras and film to digital has affected the content of my work, but not profoundly. I don’t try to poke behind the scenes for an anti-illusionist tropes, like the “hand of the artist.†Process concepts aren’t nearly so compelling now that everything has been reduced to code. But there are still plenty of windows to let in all kinds of rough, angular, mysterious stuff through Dragon captures, compositing/manipulating live action, etc. I use Photoshop and After Effects. I started AE (v.2) while doing a package of Honda spots (it took Thessia Machado and me all night to render the file sequence for layoff to video) and have never missed sprockets. I gave my beautiful little Forox to Frank Mouris and do not for a minute miss the obsessive tedium of shooting. Also important are the opportunities for presentation: digital projection, installation, the internet, etc. And, in a contrary take on progress, I think the so-called inevitable hegemony of digital animation has also created a growing creative backlash among young artists working in 16mm, making “bad animation†(Hertzfeldt?), making pro-cinematic machines and performances, combining animation with sculpture, even doing flipbooks and other kinds of physical/concrete animation.

Neither 3D nor CGI does much for me: too much hoopla, not enough substance, same old studio specialization. I never liked puppet animation (except in the hands of surrealists), so Pixar’s hyper-realism, texture, lighting and acting strike me as superficial, value-added cargo, while the content tends to channel the Disney formula. Call me a curmudgeon, but I thought the love story-in-a-nutshell in “Up†was a perfectly executed jewel using every cheap, manipulative, maudlin cliché in the book.

,

Q.Your films have always had an affiliation with jazz. KO KO, YOU’RE OUTA HERE and others have been more direct about it than others, yet the attachment is there. How do you see the relation of jazz to animation?

Did animated film and jazz emerge contemporaneously from popular American forms, vaudeville entertainment and dance bands? Did they embody the driving energy of modernism, both sophisticated and a little raunchy? Were both “animated†above all by the infectious pulse of the city, teeming with a heterogeneous, mobile, immigrant culture. OK, I get carried away. I just happen to ____________________“KoKo” (1988)

Did animated film and jazz emerge contemporaneously from popular American forms, vaudeville entertainment and dance bands? Did they embody the driving energy of modernism, both sophisticated and a little raunchy? Were both “animated†above all by the infectious pulse of the city, teeming with a heterogeneous, mobile, immigrant culture. OK, I get carried away. I just happen to ____________________“KoKo” (1988)

love most jazz because it is based

on improvisation and rhythm. The former is the gesture of drawing: rough, immediate and perhaps not too perfect. The latter is the heartbeat, handclap, call and response, but also a natural force like the ocean and unnatural force like a machine. Most animation is created by an achingly methodical process, almost deadening it its technical demands. To transcend that, to give it life, you have to make it appear to be improvised, and if you get to that ecstatic point of creativity where nothing else matters, then it WILL be improvised, only not in clock-time, but your own time, animators’ time. The most obvious examples are the direct animation of McLaren, Len Lye, Barbel Neubauer, but ideally it can extend to any decision made in sequence drawing—or any other technique—from instance to privileged instance.

Most of my films have been accompanied by some kind of printed object. The “Ko-Ko†counterpart was the flipbook, “Barrelhouse Bopâ€, which was a deliberate attempt to do a cartoon interpretation of the history of jazz with shifting styles and cadences.

“Bather” (2009)

There’s an interview with George Griffin about “Bather” here.

There’s another extensive interview with George Griffin on AWN by Ann C. Philippon here.

You can purchase a DVD of George Griffin’s work here.

on 14 Jun 2011 at 8:57 am 1.Mark Mayerson said …

Great, great interview.

You should link to the DVD of George’s films.

on 14 Jun 2011 at 9:13 am 2.Michael said …

Thanks for the reminder, Mark, I’d meant to do that and have now added the link to the DVD.

on 14 Jun 2011 at 10:14 am 3.Signe Baumane said …

YES George is an inspiration for me too!

on 14 Jun 2011 at 10:18 am 4.Jed Martinez said …

I love George Griffin’s works (having seen some of them at the Whitney Museum in NYC, many years ago). My favorite one (whose title eludes me) was an experiment in which he took the entire soundtrack from a “Tom & Jerry” seven-minute cartoon and drew new imagery set to the music and sound effects!

If memory serves me correctly, the Tom & Jerry short (George used) was “Puttin’ On The Dog” (1944).

on 14 Jun 2011 at 10:35 am 5.Pierre said …

I too love George Griffin’s work. I first became aware of him when I purchased Kit Laybourne’s book in the late-1970′s. The samples of his work that were reprinted, and the photos of him in his studio were such enormous inspirations.

As always, thanks for the great interview!

Pierre

on 15 Jun 2011 at 1:01 am 6.Sky David said …

Yes, George is one of the longest standing independent animators who has crossed the realm of personal vision (exploration) into the realm of service in the commerical animation domain. Bravo!”

on 16 Jun 2011 at 10:57 am 7.richard o'connor said …

Top notch post.

George Griffin is an inspiration not only for his intelligent, well crafted films but also his constant exploration and experimentation. He’s simply a great artist (and that’s a very complicated thing).