Photos 31 Jul 2010 08:19 am

Stonehenge

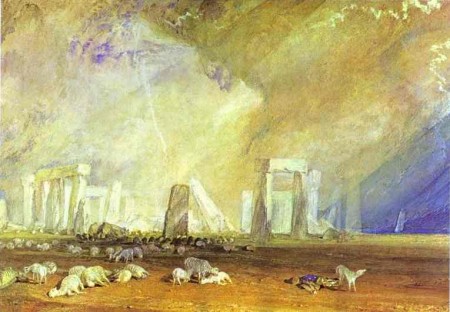

“Stonehenge” by J. M. W. Turner

- John Fowles is certainly one of my favorite, if not THE favorite author. Aside from the several novels he authored, there were a number of books he wrote to act as companions to photographic essays. Last year, I posted some work from his book on Shipwreck. This book spoke about the many ships that had crashed near Lyme Regis, Fowles home, and included many photos of these wrecks.

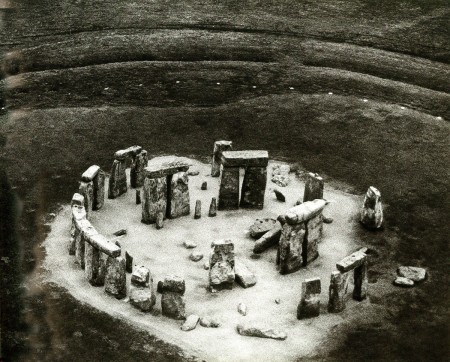

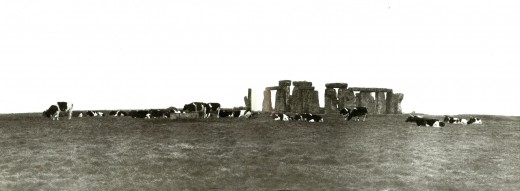

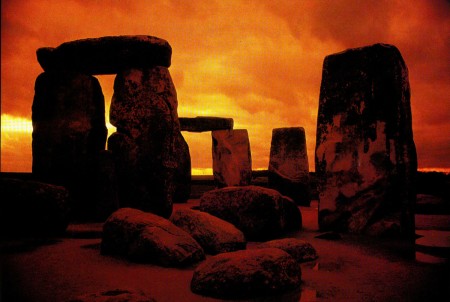

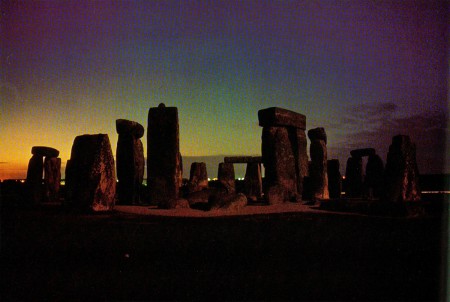

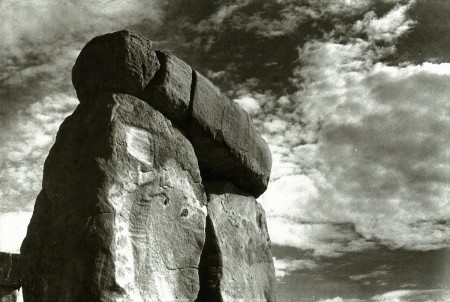

Another book of his, The Enigma of Stonehenge, accompanies the glorious photos by Barry Brukoff.

Fowles claims not to have any archeological knowledge, but he does fairly well in reporting the history and the legends behind Stonehenge, and it’s an enlightening book, beautifully written and illustrated.

I’ve decided to post the first two paragraphs of Fowles’ introduction to the material with a number of the photos – and there must be a couple hundred of them.

Thanks for tolerating my side trip from animation, at least for today.

MY EARLIEST MEMORY of Stonehenge is, like so many childhood memories, as much fiction as fact. I see a little boy standing at a country roadside. Larks sing, lapwings wheel. There across the cropped greensward the great stones rise and I run towards them, ahead of my parents – not at all, I’m afraid, as a budding scholar or an embryo Romantic. But at least I recognize a good natural exploring place when I see one. Climbing, scrambling, squeezing through stone pillars: it is not quite so jolly as Cheddar Gorge or the Valley of the Rocks, but above all it is not suburban, the world I know best. Already I know suburbia is sameness, sameness, sameness; that freedom, or my freedom, lies in the unsame; and that nothing can be unsamer than this.

One part of my memory must be very wrong, because people have not been allowed to walk up to the monument as they like since well before my birth; and even in the 19305 I am pretty sure, though one was then free to wander in the central circle, that eight-year-old mountaineers were not encouraged. But our present protectiveness and seriousness over the place is something new. Even possessing it, as late as 1915, had a remarkable casualness. A gentleman bought it at auction for £6,600 in that year. He was asked why. It emerged that his wife had happened to mention at breakfast that ‘she would like to own it’. The good man promptly sallied out and bought her her stone necklace. (She did not wear it long, however; three years later the Chubbs generously gave ownership to the nation.)

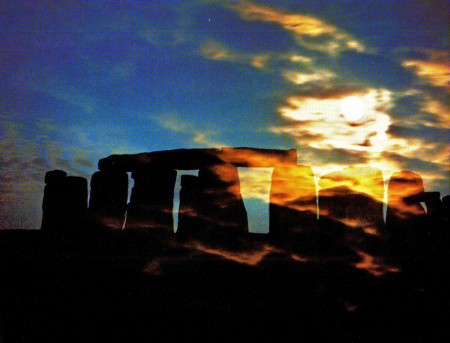

Of one thing I am certain: my own first meeting was happy. It may have been because I could not quite take that enticing clutter of boulders, so like a Dartmoor hilltop, as man-made, whatever I had been told beforehand. Almost all public buildings have always carried strong connotations in my mind of duty, work, imprisonment of one form or another – of the cell in all its senses. Where the wiser judge architecture by the way it plays with light and space, I tend to judge it by what it shuts out of those things. Stonehenge’s marvellous openness to them was what first pleased me. It came to me on that occasion, and has remained since, as the most natural building, the most woven with light, sky and space, in the world.

My latest remembrance, on a recent clear but arctic November day, is sadly different. Stone-henge stands in the fork of two busy roads, and the dominant sound in its present landscape is not the larksong of my memory, but the rather less poetic territorial whine of the longdistance truck. Visitors get to it now from a car-park, past a sunken ‘sales complex’, then down a subway under the nearest road: all this designed not to spoil the view, but the effect is unhappily reminiscent of an underground bunker. When they finally rise inside the wired-off enclosure, they are promptly faced with another barrier. The public is now forbidden the central area.

Conservation is a fine thing; yet one feels in some way cheated of a birthright, while the stone-grove itself seems deprived of an essential scale – indeed rather like a group of frightened aboriginals huddled together in self-defence against this sudden decision on our part to ostracize them so mercilessly. Everyone I had spoken to before coming had warned me that the new preserved-for-posterity Stonehenge – this was my first experience of it – makes a depressing visit. My wife, more fastidious than I am, took one look and turned back to the car.

I went up to an attendant in a little wind-shelter and explained I was preparing a text to accompany Barry Brukoff s photographs and would like to walk inside the barrier.

‘Are you an archaeologist?’

‘No. Just a writer.’

‘Department of the Environment, London. By letter.’ Then he added, ‘And I can tell you now you’ll be wasting your time.’

He looked bleakly over my shoulder at the mute clump of stones, as a prison warder might who has successfully foiled yet another clumsy escape attempt. I didn’t really blame him, for it was bitterly cold; and after all, who cares for mere curiosity and affection any more?

on 01 Aug 2010 at 9:15 am 1.Elliot Cowan said …

The whole thing is surrounded by stout cyclone fencing these days.

Classy.