Articles on Animation 24 Nov 2009 08:46 am

Alexeieff & Parker

Svetlana Rockwell, the daughter of Alexandre Alexeieff has recently sent out a letter to several people worldwide. I was fortunate to have received a copy of this via Karl Cohen, the ASIFA-SF president.

Svetlana Rockwell, the daughter of Alexandre Alexeieff has recently sent out a letter to several people worldwide. I was fortunate to have received a copy of this via Karl Cohen, the ASIFA-SF president.

- I am very pleased to be able to let you know that my father Alexandre Alexeieff’s DVD has been produced in this country by FACETS in Chicago.

The DVD was originally put together by my agent Dominique Willoughby ,CINEDOC in Paris. It took him two years to do it.

The result is excellent. It was a work of love!

Years ago, when I read and re-read the Halas/Mavell book Technique of Film Animation, I was particularly curious to see films by Alexeieff & Parker. They were hardly available – even in New York. The best I could do was to see the titles to the Orson Welles’ film The Trial. I had to wait years to see others. These days, of course, like everything else they can be seen relatively easily thanks to such DVDs.

The disc includes their most important films including the renowned adaptation of Moussorgsky’s tone poem, Night on Bald Mountain. Over 30 films are featured, including short animations, stop-motion animated advertisements made for French cinemas, and photographs of Alexeieff’s still artwork.

It also includes The Pinscreen, a documentary by Norman McLaren; Mindscape, a film by Jacques Droulin; Alexeieff and Parker Making Three Moods, a documentary; and a gallery of photos and prints.

You can order the DVD directly from Facets in Chicago.

To give more information about the noted duo, whose work is probably not as well known today as it was even 10 years ago, I post this article by Alexeieff written for Animafilm #3, Jan. 1980:

as a profession

by Alexandre Alexeieff

Does a country exist which would not seem to believe that it must possess a Museum, a School of Fine Arts teaching painting, sculpture, engraving and architecture, a Music Conservatory and an Opera House?

Does a country exist which would not seem to believe that it must possess a Museum, a School of Fine Arts teaching painting, sculpture, engraving and architecture, a Music Conservatory and an Opera House?

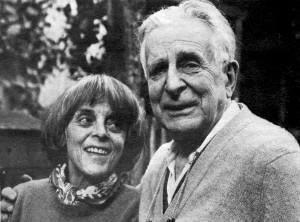

As if there were at any time and in every country great painters, sculptors and musicians… and yet History testifies that the reality is quite different: there are many countries which have never had any great painters, or else have had some, but for a limited time. ________________Claire Parker & Alexandre Alexeieff

For instance a country may have had a great poet hut never a great composer, and so on. A closer study of the history of culture shows that a period during which a given country enjoyed the flowering of one or several particular arts is hut of limited duration. Such a period is invariably followed by a gradual decline consisting of dreary routine due to an excessive respect for stereotyped rules imposed by the elders.

I am particularly impressed by the singular case of Russian classical literature, limited to the first decades of the 1 8th century. It so happened that before 1806 literate Russians spoke and wrote in French. The patriotic feeling engendered by the Napoleonic aggressions resulted in the new fashion of speaking and writing in the native tongue which, until then, had been used mainly by illiterate peasants. A handful of writers (among whom only Pushkin’s name is familiar to the West) ‘ lacking any national tradition, had to create the very language itself, in which they were’to write. Rut never since has Russian literature attained such grandeur. One is tempted to remember the famous line of the French playwright Racine: “.. .qui d’un coup d’essai font un coup de maltre…” What seemed to Racine an exception – an apprentice succeeding as if he were a master – is it an exception or, perhaps, a general rule?

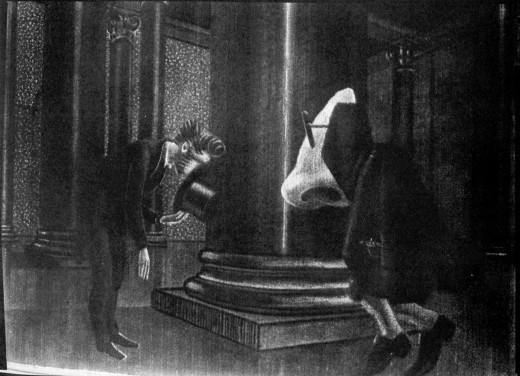

THE NOSE – (1963)

If I remember rightly, it happened around 1922, after the summer vacation was over, that the Cafe du Dome on Montparnasse, which by that time had supplanted the “Rotonde” as the meeting place of painters, opened its redecorated rooms. Its walls were ornate with new polychrome bas-reliefs of a most abominable design prevailing at that time on French banknotes. This discovery gave me immediately the strange certitude that French easel painting was dead for good. And indeed it so happened that after that year paintings of a frankly decorative character supplanted easel painting in everything but name.

I listened nevertheless to the teachings of the new masters with reverence. According to them the utmost care had to be bestowed upon COMPOSITION. Yet one had to care also about TEXTURE. Subsequently it was the preoccupation with texture, which I practised in my engravings, that resulted in the invention of the pinscreen (which is to my mind the purest example of what an engraved plate tends to be).

The year after that sad opening of the Cafe du Dome, when the pinscreen built by Claire and me empowered us to animate my engravings, I conceived that the forthcoming film of “animated engravings” was to show for the first time an image which would remain constantly composed in spite of its movement.

The very first screening of our first rush demonstrated that COMPOSITION was an affair of monumental painting and had nothing to do with movies.

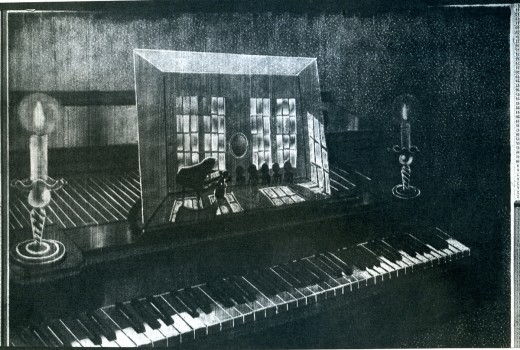

PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION – (1972)

Forty-five years have elapsed. It no longer looks scandalous to read that easel painting exists no more. In private houses the SINGLE MOVING IMAGE tends to replace static paintings. The rich no longer buy bronze or marble, or paintings in their frozen frames: they buy instead trips to the inhabited inslands of the South Seas. As if humanity were discovering movement and time. As if the ephemeral, the transitory were taking the place of the eternal, the solid, the permanent. One no longer cares about the Seven , Wonders, one bids farewell to Antiquity.

Leaving the three-dimensional, humanity is entering into the fourth dimension.

One may suppose that animation’s destiny is to take the place of painting. Whether decorative or easel painting, does not matter – painting being lost in a maze of sterile scholastic speculations.

Is animation going to live side by side with that sort of animated photography which people call the cinema? Probably – yes, and yet the cinema will have to make some room for animation.

NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN- (1933)

It was in the early 1930s that I saw Renoir’s film showing a white horse galloping on a background of dishevelled clouds. Apparently it was a double print: there were two shots, one of a horse and one of clouds. One of the prints was printed over the other… but I wondered what Renoir’s role was in all that. Dtdn’t he have to accept both horse and clouds such as they were? Certainly it was Re’noir who decided to print the two shots one over the other… was this all he did? Was his part of creation no more than combining recorded real events?

After 45 years, as I understand it motion picture animation is an acceleration of images and events entirely created by the imagination of the artist. These he has to slow down during the step-by-step process of creating the film.

When it crossed my mind to count the days, weeks and months which Claire and me had to spend under the lens of our camera in order to cumulate that time into no more than eight and a half minutes of film, I realised that this was a ratio of about 30,000 to one; reciprocally it might be said that we slowed down an 8 minute long action to some 540 days. There were days when I lived only a fraction of a second during the whole 6 hours of work. This required a discipline yet unknown to me in spite of the pretty hard training I was familiar with as an engraver. The thing looks to me like a sort of slow motion, but now not applied to film hut to human life itself: my life. This had to he so drastically slowed down in order to endow with life an image conceived and made hy me – an image or images of things which (unlike Renoir’s horse) never existed anywhere except in my mind.

ACCELERATION? I had to examine that. From the start it occurred to me that ACCELERATION is the reverse of SLOW MOTION.

ACCELERATION? I had to examine that. From the start it occurred to me that ACCELERATION is the reverse of SLOW MOTION.

Who can remain indifferent hefore the grace of human and animal movements slowed down?

And yet, why does an acceleration (even a slight one, which is undergone by old films shot at 16 frames per second when screened at 24 f.p.sec.) -why does even so minimal an acceleration invariably look funny.

And more: are there other mechanical accelerations known among the arts? Yes, there are gramophone records of funeral marches which, if recorded at 33 revolutions per minute, sound like gay polkas when speeded up to 78 r.p.min. And in the reverse: a polka, recorded at 78 r.p.min, sounds grave and majestic if played at 33 r.p.min.

It is also illuminating to ponder over the instructions for the speed and character of the interpretation of musical scores: “moderato pesante” or “allargando” or “perdendosi” or “tranquillo”, if not “scherzando” or “andante grave”, even “con dolore” or “allegretto vivo” as well as “feroce” or “maestoso”.

But how about “30,000 times faster”? This is much more than simply faster than “twice as fast”… Here the acceleration is so tremendously out of proportion -could quantity perhaps change the very quality? We cannot answer such a question, but we may note the general trend of animation to rush out of the control of the animator, who is invariably suprised on seeing his shot screened for the first time.

But let us admit also that it is monstrous to spend 18 months for 8 minutes of movement… And then there is that absence of slow motion, which animation ignores… that lack of gravity… that perpetual agitation… that compulsory burlesque… Is it possible that animation cannot do SOMETHING ELSE, as music can?

If I took the liberty to thus speak my mind, it is because I’ve been thinking along these lines for a very long time, I wonder whether some other people do not think like this as well. It is for them that I’m writing.

Doubtless I am not alone in wishing for an evolution. Others than me – Szczechura for instance – are revolutionizing animation admirably.

I also admit that serious subjects have never been well paid for, although burlesque brings in cash. But is big money so important? Impressionist painters did not make money during their lifetime.

The history of the fine arts is like the card game named “patience”. A solitary game where the cards open their faces one after the other. The future will show what animation can do.

The history of the fine arts is like the card game named “patience”. A solitary game where the cards open their faces one after the other. The future will show what animation can do.

By the way – is there an animator who wouldn’t wish to speed up his production process? This implies the reduction of the ratio between production time and screening time (speeding up production spells out slowing down the acceleration). Therefore Claire and I are presently trying to reduce the speed of out animation to the tempo of slow motion, and I believe we can do it… at least sometimes. Last spring we succeeded in going 50-timcs slower. If we were shooting NIGHT ON BARE MOUNTAIN these days, we might reduce the ratio of 30,000 times to 600 which is almost tolerable.

English version corrected by Claire Parker

©1979, by Alexandre Alexeieff and “Animafilm”

Claire Parker collaborated with Alexandre Alexe’ieff in the production of all his films made on pin screen. She took part in the animation of all his films, excluding three commercial films which he made in Berlin, and LA PLUME DE F1N1ST – CLAIR FAUCON, made in Rome. The film biography covers their joint work.

Claire Parker collaborated with Alexandre Alexe’ieff in the production of all his films made on pin screen. She took part in the animation of all his films, excluding three commercial films which he made in Berlin, and LA PLUME DE F1N1ST – CLAIR FAUCON, made in Rome. The film biography covers their joint work.

1931 – work on the first pin screen: 500,000 little rods sharpened at one end, with a diameter 0.9mm. Surface: I x 1.20m.

1933 – first film, UNE NUIT SUR LE MONT CHAUVE (The Night on Mount Bald). Extremely warm reception of audiences, but poor distribution; six weeks at Pantheon (Paris) and two weefcs at the Academy (London).

1934-LA BELLE AU BO1S DORMANT (The Sleeping Beauty), the first color puppet film starring puppets used for advertising “Nicolas” wines. Cooperation with Jean Aurenche and Francis Poulence. Alexe’ieff gives up puppets and script writing for professionals.

1935-1940 – commercial films (color) with object animation. Cooperation with top European composers. New effects included in ads films of up to three minutes. Friendship with Bartosch.

1937 – an attempt at making a smaller pin screen: 50×65 cm with a simplified structure – a failure.

1940 – A.A. and C.P. find refuge in the U.S.A. Friendships with Canadians, especially with N. McLaren.

1943 – second pin screen. Dimensions 1×1.70 m, 1,400,000 sharp-pointed rods. Diameter 0.45 mm. EN PASSANT (Incidentally) – a film commissioned by the National Film Board of Canada. Lack of interest in this film in the U.S.A. Walt Disney imitates “The Night on Mount Bald” and A.A.’s GRAND FEUX POUR ARTHUR MARTIN (Great Fire for Arthur Martin), but the Americans are somehow distrustful towards Continental artists.

1947-back to Europe; problems: shortages of paper and electricity.

1951-TOTALISATION(Totalization), fortheBel-gian producer Paul Delpire, originates. The film FUMEES (Smokes).

1956 – Films: SEVE DE LA TERRE (Earth Juices), MASQUERS (The Disguised), PURE BEAUTE (Pure Beauty). Admission to the Cineastes Associes.

1963-LE NEZ (The Nose).

1964 – last, 31st commercial advertising film, DE L’EAU (The Wafers,). The producer congratulates A.A. and C.P. on the film but fails to screen it.

1968 – new pin screen with a- more complicated construction. Dimensions: 45×55 cm., 250,000 sharp-ended rodlets. Diameter: 0.45 mm.

1972 – the film TABLEAUX D’UNE EXPOSITION (Pictures at an Exhibition), made on two pin screens. National Film Board of Canada purchases the new screen made by A.A. and C.P.

1975 – an exhibition at the Annecy Castle.

1977 – another pin screen completed. Dimensions: 50×60 cm.; 275,000 rodlets pointed at both ends. Diameter: 0.49 mm. A new film in store, TROIS THEMES (The Three Themes).

Color Images #5-#8: Graphics by Alexandre Alexeieff

on 24 Nov 2009 at 10:13 am 1.Elliot Cowan said …

We watched this film in 16mm as part of our Monday morning screenings when I was at University.

There was also a nice documentary about how they were made (from what little I recall).

on 24 Nov 2009 at 3:26 pm 2.Ray Kosarin said …

An astonishing talent. This interview–and, I must think, the DVD–are like finding buried treasure.

‘Night on Bare Mountain’ is groundbreaking, exquisite, and savage. More powerful in its way than Bill Tytla’s in ‘Fantasia’ just a few years later (and that’s saying something!).