Articles on Animation 11 Jun 2009 07:46 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

Needless to say, these are all outdated pieces, but there’s some entertainment (at least) to be gathered from reading these reports. The first, naturally enough, came from Great Britain and – appropriate to the times – is Halas & Batchelor-centric.

All of the essays talk about the effect UPA has had on the medium, most particularly Phillip Stapp’s report of the USA. (I’ll probably post that one next week.)

Here’s the state of England in 1957:

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

In Britain, animation is a family business, operating in the style of the medieval craftsmen’s guilds. The Units tend to stay together in small communities, usually in converted houses or tiny offices. Personnel grow up with their production companies, often entering the business direct from University or Art School. Training is done by experience, as the young learn from the old in the day-to-day work at the animation tables. There is a struggle to maintain continuity of production. Leadership is based on the personality of one or two people who often manage the whole operation as a kind of family concern, imposing their style to a degree which they themselves would scarcely admit, for many strive to encourage as much individual experiment as possible amongst those who work for them.

The Units are divided into four main categories. First, there are the groups who produce sponsored films but, because they have been in existence for a long time and have established some measure of independence, are able to conduct occasional experiments that lead to theatrical distribution, or even to produce films specifically for the entertainment market. Halas and Batchelor Productions are a Unit of this kind.

John Halas came to this country before the War, having worked in Hungary with George Pal; Joy Batchelor first met him in London and shared in the making of animation films, both here and in Budapest. They married and now operate the company under joint control. Like most British Units, they depend on sponsorship of various forms for their existence. This comes from three main sources:

Mr. Finley’s Feelings, Earth is A Battlefield, __1. Official Bodies, Government Departments

Britvic Commercial, The Gas Turbine. ______or International Authorities.

_____________________________________Examples of films made recently in this category include To Your Health, for the World Health Organisation: Basic Fleetwork, for the Admiralty; The Sea, for the Ford Foundation; and The Candlemaker, for the United Lutheran Church in America.

2. Sponsorship through Industry. Recent films include: Power to Fly, for the British Petroleum Company, and Invisible Exchange for Shell.

3. Direct Advertisments, made now mainly for Commerical Television. Halas and Batchelor made the famous Murraymints series, as well as a special series for Dunlop.

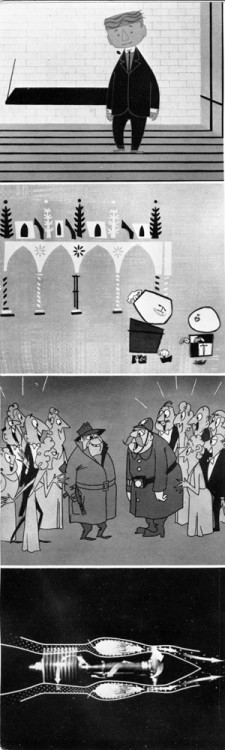

Using the resources gained over years of work in the “bread-and-butter” business, Halas and Batchelor have been able to amuse themselves (and very large cinema audiences) with such pictures as their delightful History of the Cinema, which was chosen for the Royal Film Performance in 1956. Of a more serious character was the feature length Animal Farm, a rare example of an attempt to use the cartoon film for the interpretation of a complicated political satire. The Unit that made these films is now ninety strong; it is run personally by John Halas and Joy Batchelor, both of whom are active at every stage in the making of the films as well as handling the complicated business problems that arise in sustaining the flow of the sponsorship so essential to their continued existence. The shaping of spiralling movements around little twirls of Matyas Seiber’s clever wood-wind orchestrations in well-known tunes is characteristic of their work, as well as a love of perky, bouncing little men who tackle everything from Income Tax forms to oil-well drilling with a gay, impertinent but pleasing confidence.

Halas and Batchelor produced the first feature-length cartoon in this country (Animal Farm), the first stereoscopic experiment in animation (The Owl and the Pussycat), and the first major puppet-animation production (Figurehead). Ever since their formation in 1940, they have remained completely independent of any financial links with other organisations.

The second type of Unit in Britain is that devoted entirely to sponsored work, but taking full advantage of the chances offered them by enlightened business concerns to experiment. The William Larkins Studio, operated by Geoffrey Sumner and Theodore Thumwood, was started in 1942 under the name of Analysis Films. It became part of the Film Producer’s Guild in 1947 and, as Larkins Studio, has since produced about 820 short animated films. There are seventy people in the Unit, which turns out about 30,000 feet of final-cut material a year. Personnel tends to remain static, and the Unit’s tradition in training can be gathered from the fact that, on a recent prize-winning film, the average age of the production team was 23.

As in the case of Halas and Batchelor, :ertain of their films have broken through to he theatrical field, although they have not so ~ar made films except to order. Men of Merit, “or example, was shown in some 3,000 cinemas in this country alone; 602 copies were printed by Technicolor. The studio’s style is still, perhaps almost unconsciously, influenced by the work of Peter Sachs, notably by his angular figures, clear-cut lines and sharply-defined backgrounds, in which detail is reduced to a minimum. Earth is a Battlefield, their current production, has a clever extension of the technique in a series of disjointed, cut-out figures which perform to a sound track in the rhyming style of Enterprise, an earlier film by Peter Sachs.

The third main type of animation Unit is exemplified by Nicholas and Mary Spargo’s group at Henley-on-Thames. Formed to produce material specifically for Commercial Television, the Unit now consists of eleven people working in a large room over a shop in the centre of the town. Following the well-established pattern, there are already two trainees in the group, working on the fifteen, thirty- and fifty-second commercials for which the Unit was set up. Because they are lively and imaginative, work flows at a fast pace; Nicholas Spargo spends much of his time on the business side at the moment, while his wife is usually to be found in the studio. Both gained their experience in the tough school of the David Hand Unit at Cookham.

In addition to the independent units, there are a number of small animation groups in Britain attached to certain large organisations like the Shell Film Unit. Francis Rodker and a small team of specialists have been producing excellent diagrams and animated sections for the Shell Unit since its formation in 1935. Three animation cameras are in use, each producing about 4,000 feet of exposed film a year.

A Short Vision, Down a Long Way

Finally, there are the experimental groups, whose status borders between professional and amateur. Typical is the case of Joan and Peter Foldes, who produce animated films in their own home in Edgware. Peter Foldes, like John Halas, came to London from Hungary; he met his wife here and they now work together on all their films. Animated Genesis, their first film, was made on their own resources up to picture rough-cut stage. It was then shown to the British Film Institute, who persuaded Sir Alexander Korda to see it; he completed the sound track and gave the picture distribution through British Lion. A Short Vision, the six-minute story of an artist’s impression of the world destroyed by nuclear fission, was also made as a private venture in the beginning; it was completed with the help of the British Institute’s Experimental Production Fund, and later shown on American television.

The personal quality of British animation films derives from the struggle for independence, the imprint of a beneficent sponsorship and the style of those who founded their own groups and continue to run them. The system is not without drawbacks. Experiment, especially in subject matter, is always subordinate to the needs of the sponsor. Full public screenings are the exception, however delicate the advertisement. The Units are too busy with their own work to indulge in large-scale publicity. They have to contend with the fact that the major circuits are, by-and-large, completely deaf to their work. By contrast many European countries encourage the work of their animation units.

In spite of these difficulties, British animated films have won many international awards. These films are being used increasingly in the United States, both in the cinemas and over television. The battle for a screening is being won at long last; in every country, except Britain.

on 19 Oct 2009 at 8:16 am 1.Ian said …

This article starts by talking about Halas & Batchelor – my first job in animation was for Halas and Batchelor, by then Joy (Batchelor) wasn’t involved in the business and they were doing Network TV series for the US, The Jackson Five was my first production.

The article mentions how John Halas worked with George Pal.

It then goes on to talk about the Larkins Studio (latterly The Guild) and my Father, Peter Sachs. He also worked with George Pal in a studio in Berlin and then, just before the war to escape the Nazis, Antwerp, Holland. From there George Pal went to Hollywood and my Father went to England where he was interned.

The third type of studio mentioned was Nick & Mary Spargo’s in Henley. I met Nick when he worked for Bill Melendez as one of the directors on the Emmy winning production of “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.”

Later we (my wife and I) worked for him (paint and trace) on his own TV series “Willo the Wisp” By then I had worked in animation without any ambition to work in the industry for about ten years, injury had put paid to my chosen career as a soccer player, so I really didn’t know what to do with my life. With both my Mother and Father working in animation it was an easy stop gap for me, but the year I spent working for Nick on his TV series changed my perception of the industry. Before I had worked for bigger companies but with Nick it was a real cottage industry style of production. There were just 8 people on the entire series, Nick wrote and directed, he had his studio in his garden (a big summer house) and meetings where a combination of looking at the work in his summer house and discussion at the local pub over lunch. I really think that was one of the best working years of my life and I loved the idea of writing and directing, just like Nick.

Within a couple of years I was writing and directing TV series for FilmFair, where I stayed for 8 years as Director of Animation.

So reading the article was a bit like a trip down memory lane for me, even though I was barely born when it was written and started work for H & B in the 70s.

There was just one thing in the article I wanted to comment on. As I mentioned earlier I met Nick working for Bill Melendez (famous for the Charlie Brown films) and Bill told me that in the early UPA days they were looking for a different style than Disney, something to define themselves as different and they bought a lot of European films to study, including films made by my Father, so the UPA style was influenced by European design. The article indicates the influence was the other way round.

Who knows for sure which way it really was, but that is what Bill told me.

Thanks for posting the article.

IAN