Articles on Animation 09 Jun 2009 06:45 am

Working for Lantz in the ’30s

- 22 years ago, “The Walter Lantz Conference on Animation” was held in LA. There were numerous gatherings and talks about animation on a few sunny days in LA. I got to meet a number of fine people there, but, in my usual shy manner, stayed a bit to myself. I did enjoy the event. I can’t remember going out specifically for that, but I was there just the same. My memory is a bit shaky about it. I know there were other conferences that I didn’t make.

A publication, The Art of the Animated Image was an Anthology that was published by AFI and edited by Charles Solomon. Writers such as John Canemaker, Cecile Starr and Donald Crafton wrote for it. The late, great Leo Salkin wrote this short piece which I thought might be interesting to some folks who haven’t seen it.

in the 30′s

A Reminiscence

BY LEO SALKIN

I went to work for Walter Lantz on March 3,1932. At that time he was producing Oswald The Lucky Rabbit cartoons for Universal Pictures. It was my first job. I had had an interview with Walter a couple of weeks earlier; he reviewed my portfolio of cartoons, drawn while I was at Hollywood High, and on the basis of that interview he hired me. It was the era of Prohibition, bathtub ginjohn Held, Jr. drawings, and the Great Depression. I was to be paid $17.50 a week, which seemed to me an enormous sum.

My duties were to wash cels, help in camera, learn to ink and paint, practice inbetweening on my own time. There was no training program: You picked up what you could as .you went along. During that time economic conditions were bad and getting worse, and while you were trying to learn how to ink and paint and flip animation drawings, you were never free of the fear that this job couldn’t last and that at any moment Universal might decide that they didn’t want any more cartoons and the animation department would be closed down. They were scary times but fortunately Walter managed well and we kept going.

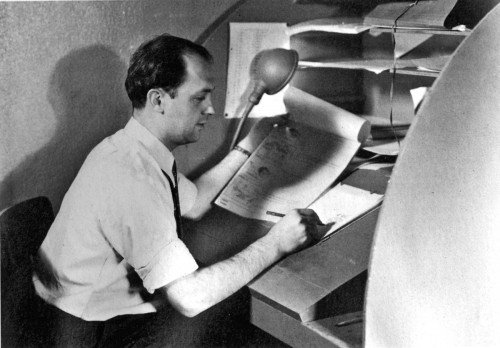

Walter Lantz at his drawing table, Universal Pictures, 1928.

In time, I learned how to animate a walk cycle, a run, a squash and stretch action, and something about the mystique of the exposure sheet and animation timing. After awhile I became a pretty good animator. And somewhere along in there I learned about gags. As a matter of fact, there was no way you could have avoided learning about gags: They were the life blood of the place.

What I value most about having worked for Walter in those years is what I learned about gags. The work days in the studio consisted of two major activities: one was making animated cartoons; it was the primary reason we were there, and it was the basis of our livlihood. The second activity, only slightly less important than the first, was drawing cartoon gags of each other. That; was a big thing. And it took place simultaneously with the production of the films. What was remarkable about the situation is that Walter not only tolerated and accepted it, he, at times, contributed and took part in it. And despite the horseplay, production schedules were met and budgets were contained.

It would be absurd to describe the atmosphere of the place as playful—that’s too refined—it was a funny place. It was a place of gags. The physical environment in which we worked influenced the kind of gags that were played. The animation building was a one-story structure. One side had windows running the length of the building. The interior was divided down the middle by a seven-foot high partition. The ink and paint girls were on the side by the windows—they provided a big part of the audience— and the animation department on the other side was in semi-darkness. It was the semi-darkness that seemed to have nurtured the particular kind of nuttiness that took place.

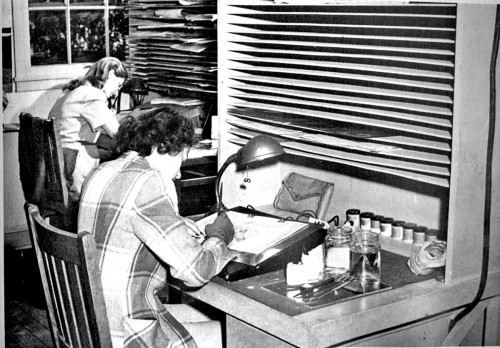

Inking and painting tables, Universal Pictures.

There were the physical gags like filling a small paper envelope-type of cup with water then pinning it to the bottom side of your animation board so that it slowly dripped on to the crotch of your pants as you were sitting there drawing. Tnere were the eraser gags in which someone would place a piece of rubber eraser on top of the hot light bulb under your animation disc and then wait eagerly for you to become aware of the stench that was enveloping you: There were the hot-foot gags—in fact that was the era of the hot-foot. Most of the guys smoked. Everybody carried matches. The room was in semi-darkness. The entire under-structure of the desks was open: four legs and a cross-piece to put your feet on. Perfect set-up.

And the imbecility went on endlessly. Then there were the belching gags—a standard after-lunch performance: A very loud belch. Voice in the darkness, “Are you okay?” Second voice, “Yeah, I think so.” “You didn’t tear anything, did you?” “No, I’m okay.” “You want some water or something?” “No thanks, but thanks anyway.” “Okay.” Finally, there were the so-called practical jokes which were plentiful, at times painful, embarrassing, humiliating and stupid.

Now we come to a special category which 1 treasure: the personal cartoon gags and caricatures. They were indigenous to the animated cartoon studio. Everybody in the place could draw. The ability to draw was almost a cheap commodity. The personal cartoon gag was the dominant form of communication; people expressed what they felt and observed in cartoons. Anything that happened during the course of the day, however trivial, was potentially the basis of a cartoon. The event could be blown up out of all proportion to what had actually occurred; it could be seen as ridiculous, absurd, pathetic, idiotic, or whatever. The gags were sometimes tasteless, crude, vulgar and obscene,but they generally got laughs.

To analyze why this provided so much pleasure—at least to everyone but the butt of the joke—would require another reading in the psychopathology of humor, and I’d rather avoid that. I think the guys wanted to have fun, to find relief from the boredom of flipping animation paper all day long.

The ability of the artists to create a strikingly recognizable likeness of whoever they were cartooning was extraordinary. Whatever was characteristic and unique about any given person

would be pounced upon, exaggerated and burlesqued, and combined with some personal incident, made a continuing source of cartoon gags and caricatures. Sometimes the way they drew you

would be embarrassing, “My God! I don’t look like that, do I?” And the only person youieould turn to for consolation was Robert Burns:

“O wad some power the giftie give us

To see oursel’s as ithers see us!”

We were granted that.

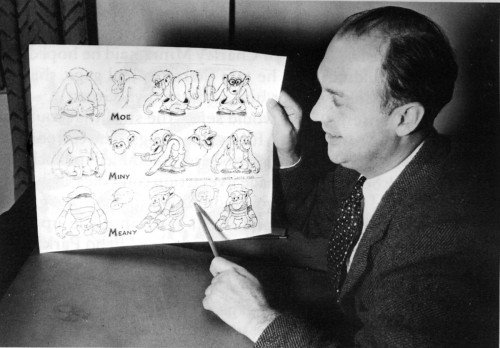

Walter Lantz with a model chart.

This brings me to that stage of development in which I began to learn something about the nature of gags, their structure and function in film. In the early ’30′s Walter Lantz didn’t have a story department. Walt essentially put the stories together with the contributions of a number of people who had shown an ability to think funny and to come up with gags for the films. The way it worked was this: first a subject was chosen: Oswald Camping Out or Oswald at the North Pole or a take-off on King Kong; then a notice was put up on the bulletin board asking those interested to turn in gags; this was followed by a story meeting. The guys called into the meeting were people who had turned in gags—at that time I remember there was Tex Avery, Cal Howard, Jack Carr, me, a few of the key animators, and Walt.

A story meeting, for those who have never attended one, was an extraordinary experience. The prevailing atmosphere was a mood of What the hell, it’s okay to say anything that comes to mind, what’s important is getting laughs. The out-going, extroverted, comic naturals had a hilarious time. For some of us to whom this was unfamiliar territory, the uninhibited, right-off- the-top-of-their-head-shouters were a bit intimidating. There was a lot of talking and laughing and making jokes. Sample joke: in one story meeting I remember Jack Carr, an inveterate punster, who had previously worked for Charley Mintz, said he hoped the Lantz group wouldn’t think he was there to steal gags, that he hoped they wouldn’t consider him a Mintz spy. (Groan).

Out of the nonsense Walt would select the stuff that could be made into a film: comedy bits, funny lines, gags. The cartoons of that period were still being concocted and assembled in much the same way Mack Sennett had made live-action comedies: “Charlie, there’s some kid auto races going on down in Venice—grab a cameraman, go down there and see if you can come up with something funny.” Or, “Hey! They just drained Echo Park Lake, it’s all mud, that oughta be funny as hell!” That’s what we did. We took a locale, an occupation, a situation, or the basic premise of a popular feature and did a lot of gags, strung them together, built in a chase, and got out in under seven minutes.

There was no market testing, or who is our target audience, or will a sponsor buy this? Come on, fellas, it’s just comedy. Get some laughs. Walter was the judge. What he thought was funny was what got up on the screen.

Story meetings despite all the laughter and kidding around had a lot of emotional tension running through them and you had to enjoy doing story to be able to cope with them. Bill Nolan, who co-directed with Walt, was one of the great innovative animators of the late 1920′s period, and he disliked working on story. In fact he hated it, and most of all he hated puns.

We were having a meeting with Bill on a story that Tex Avery, who was then the key animator on the Nolan unit, wanted to develop. It was to be based on a popular song of the period. “I Found a Million Dollar Baby in the Five and Ten Cent Store.” There was the usual amount of banter and gossip and making jokes and Bill was getting increasingly restless, irritated and annoyed. Then someone made a casual remark about how you could sure get some good buys in the dime store, and at that point Jack Carr, the pun man, said, “Right! I mean everybody knows that whatever you get at the five and dime is Woolworth every cent you pay for it!” That did it. The last straw. Bill Nolan jumped up, lunged at Carr and had to be forcefully restrained from punching him out.

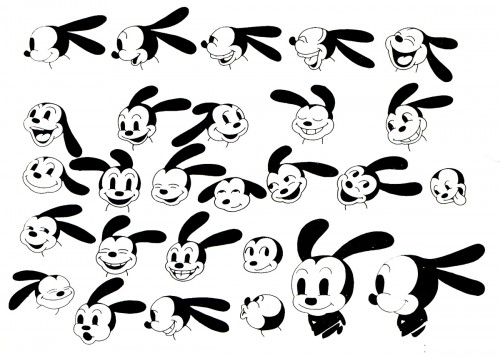

Model chart for Oswald The Lucky Rabbit, 1928.

The dynamics of a story meeting were instructive: You were in a competition to be funny, to get laughs. Your mind was totally involved—the right hemisphere, the left hemisphere, the conscious, the pre-conscious, and the unconscious—all trying to come up with that funny bit that would get a laugh. And suddenly you got it. “Wow! Wouldn’t it be funny,” you’d say to yourself, “if Oswald did this and then he did that and then he…” And then you’d stop. “Damn! That’s a gag I saw Chaplin do. I can’t suggest that. I didn’t think it up. That’s stealing.” And right at that moment, somebody else would jump up, say exactly what you were going to say and everybody would laugh and say, “Terrific! Hey, that’s funny!” And you’d be sitting there thinking, “I can’t believe it. Don’t they know that gag was already done by Chaplin or Keaton, or by Harry Langdon or Harold Lloyd?” It was but that was totally irrelevant.

What you had to learn was that it didn’t matter a damn that a piece of business, a comedy bit, a gag, had been done before, and who had done it. Those gags were like common currency, coin of the realm. They belonged to whomever thought of them. And a good memory for gags could be a valuable asset. What made a gag yours was the way you did it. Talented comics made the old stuff look new, mediocrities made it a bore.

You learned your craft as a gag man by doing gags, getting them in a picture, then going to a preview—imagine previewing a cartoon—at the Alexander Theater in Glendale and seeing if they got laughs. There was something ludicrous about the experience, in that the intensity of your emotional involvement didn’t seem justified by the actual event: screening a cartoon. Nobody went to the theater to see a cartoon. At best it was an amusing filler till the feature came on. Big deal. But here you are, sitting there in a cold sweat waiting for the film to unwind, waiting to see if your gag got a laugh. All you’ve got is one gag in the picture. Nobody in that entire theater knows you did it, or even gives a damn. You wait. The gag comes on. If it got a laugh you were ecstatic. Exhilarated. You just sat there in the dark and beamed. If it didn’t get a laugh the failure was personal and embarrassing. “Damn! How could I ever have thought that gag was funny?”

That’s the way it was. A gag got a laugh or it didn’t. The audience was live, there were no laugh tracks to fall back on. There was Walter Lantz and the studio, and you went back to the drawing board and tried again. And again and again.

That was my initiation into the world of cartoons. Walter made that possible. I felt privileged to be there. I used to be delighted when someone I had just met asked me what I did, and I could say,

“I’m in animation—you know, animated cartoons.” Then I would hand them my card which said, “Oswald Cartoons, Universal Pictures,” and there in bright orange, black and white was a smiling Oswald pointing directly to my name.

on 09 Jun 2009 at 11:09 am 1.Eddie Fitzgerald said …

This is the best description of the way gag cartoons were made that I’ve ever seen. Now i want to read anything I can get hold of by Leo Salkin!

There should be an ebook on Bill Nolan, I say ebook because that format can be illustrated with cartoon clips. His work on the black and white Oswalds was outstanding!

on 09 Jun 2009 at 11:18 am 2.Mark Mayerson said …

This is a great memoir, evoking the casual nature of early cartoon production, but that casualness was a mixed blessing. The small size of studios and the flat management structure meant that people could contribute in multiple areas and weren’t confined to a single job. The loose nature of the stories meant that anybody who wanted to could contribute. All of these things are what made the studio a relatively comfortable place to be (albeit during a time of economic uncertainty).

But you can’t avoid the fact that with a few exceptions, the cartoons that came out of the Lantz studio during this period were mediocre. The emphasis on gags was a substitute for understanding character’s personalities. The lifting of gags from earlier films points to valuing a laugh over a consistent point of view.

Salkin went on to do better work at other studios (his article on the making of Pigs is Pigs is great and the film is better than the Lantz cartoons he references here). No doubt Salkin learned a lot at Lantz, as did others, but it took outsiders, who developed elsewhere, to raise the Lantz studio to the first rank before economics dragged it back to mediocrity.

on 09 Jun 2009 at 11:19 am 3.john said …

Spectacular, insightful, evocative stuff!

on 09 Jun 2009 at 12:25 pm 4.Paul Spector said …

I think you might just have inadvertently solved the very first job my father had — I could never remember the exact details (what kid listens to their parents with more than one ear?) In 1930, at 16-years old, my dad was suspended from high school for arguing with his art teacher. Rather than return, all 5’6″ 120lbs of him found an audience with Walt Disney, who told him that he should go back to school and that afterward “there would always be a job for him at Disney.” Instead he, as I remember hearing it, “…walked across the street to…”. “and got a job right away”, washing cels, etc. And that’s where I’ve always been mixed up, because I couldn’t totally recall the “NTZ” suffixies, LaNTZ/MiNTZ. Mintz is substantiated, but I could never trust my judgement if I was hearing “Lantz” correctly. However, I always thought it to be true because on a makeshift resume he typed decades later, he mentioned Universal. Also, those juvenile gags they played on each other are “exactly” what I remember hearing.

Thanks brother!

on 09 Jun 2009 at 3:07 pm 5.Thad said …

Wonderful stuff, thanks for sharing. That Oswald model is obviously from 1932/33 though, not 1928.

on 09 Jun 2009 at 11:08 pm 6.John said …

The Nolan-Carr story sounds like a real-life version of the “standing army” pun by Chico Marx in “Duck Soup”, that leads Groucho to lunge at him as he runs out of the room. Great stuff.

on 11 Jun 2009 at 2:39 pm 7.John Braxton said …

Cigars Online

“Wonderful stuff, thanks for sharing. That Oswald model is obviously from 1932/33 though, not 1928.”

True..

I love the pictures you posted. thanks.

on 09 Jul 2009 at 12:41 pm 8.david said …

I love this picts! thanks for sharing man

on 05 Jun 2010 at 11:51 pm 9.Vivian said …

There is a 2nd volume in this anthology series, edited by John Canemaker, with contributions by many of the same people, from the 2nd annual WL Conf. on An. It’s called “Storytelling in Animation: Art of the Animated Image” (1988).

What I need to know is: was there a 3rd annual WL conf on anim. and if so, is there a corresponding 3rd vol??

Please email me or post if you know. It’s for a dissertation that’s being defended very, very soon.

Best,

Vivian

on 17 Apr 2012 at 6:10 am 10.sacred heart diet said …

Thank you for another informative blog. Where else could I get that type of information written in such an ideal way’ I’ve a project that I’m just now working on, and I’ve been on the look out for such info.