Search ResultsFor "dumbo"

Animation Artifacts &Books &Disney &Illustration 12 Apr 2011 06:56 am

Goliath II

- I feel very fortunate. Jason Hand, following my posts on Bill Peet’s great book illustrations, has sent me the illustrations to the book, Goliath II. This book grew out of the Disney featurette. Peet, in his autobiography, says he pulled the story from one he had written to be made into a book. When he was in the doghouse at Disney, sentenced to working on commercials for the likes of Peter Pan Peanut Butter, he stopped Walt in the hallway and showed him the story outline. Disney put it into production immediately.

It was an important film in that it was the first to use Xerography to copy the animators’ lines onto the cels. This was an extremely important step before they moved onto 101 Dalmatians.

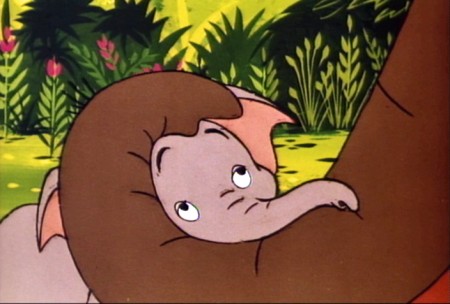

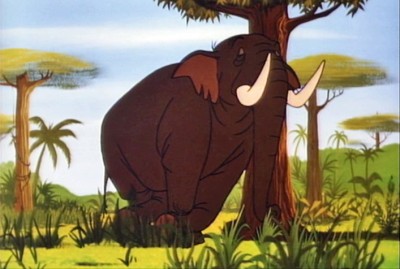

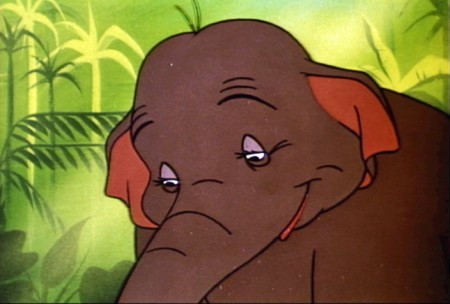

I thought this was a great invitation for me to add some frame grabs from the film which match the illustrations of the book, to see how closely the two matched. After looking at the book, one can see that the film is very two dimensional. Every action happens east – west. None of the action moves in perspective (toward or away from you). This, of course, is a product of the limited budget. The film is also all closeups. Little of the action takes place in Long Shot (the better to keep the budget down.) The film, naturally, is a disappointment when compared to Peet’s illustrations.

Here are the illustrations followed by the correlative frame grabs:

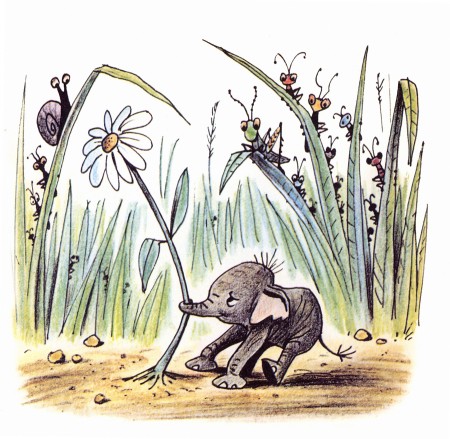

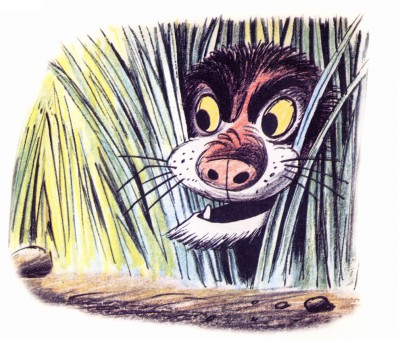

1

1A delicate drawing of something that doesn’t appear in the film.

1

1

The closest thing to floating dandelions is Goliath watching

a couple of fireflies toward the last half of the film.

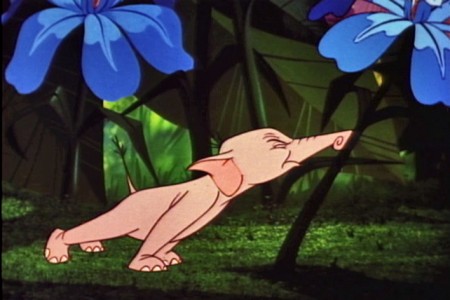

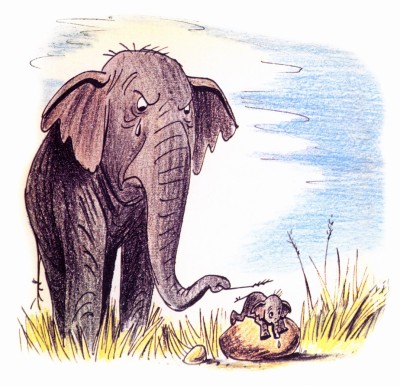

3

3

This scene isn’t played well in the film.

It’s perfectly clear in the book.

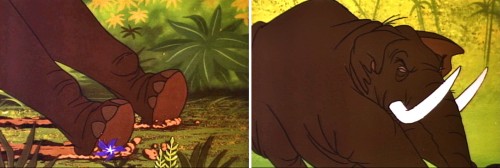

4a

4a

They couldn’t handle this scene in a single shot.

They broke it into two closeups. TV direction.

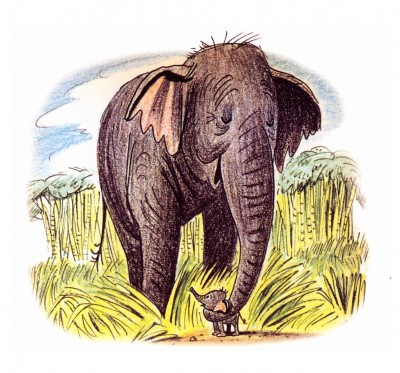

5

5

This is about as close as I can come to a match.

Peet’s drawing is so full of life.

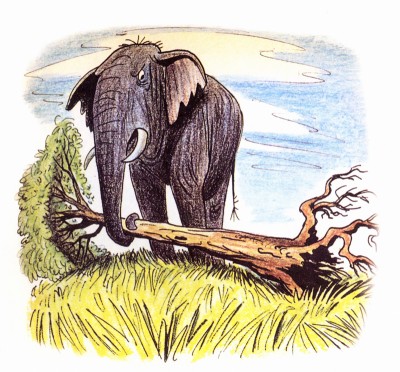

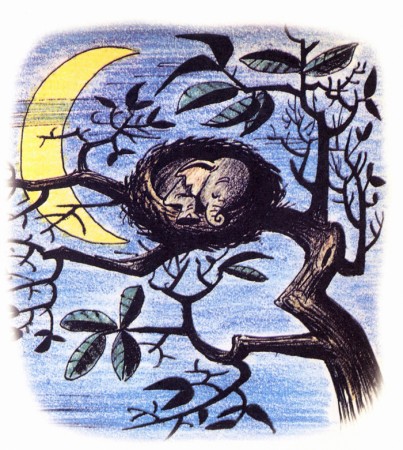

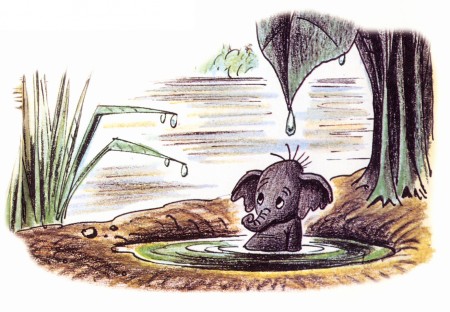

7

7

This scene actually comes later in the film.

There was no bathing scene early on.

8

8

No relation to this scene is in the film.

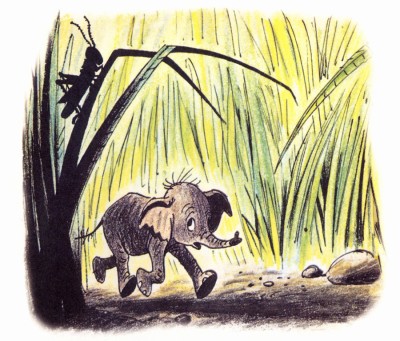

9

9

There’s no real correlative to this illustration in the film.

The closest appears toward the beginning.

10

10

More John Lounsbery than Bill Peet.

12

12

A very different approach in the film.

14a

14a

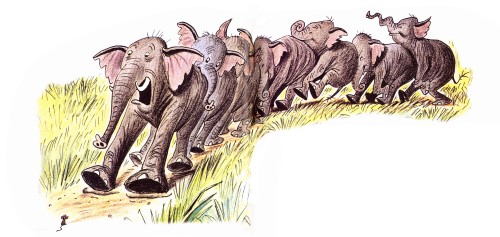

The elephant pile up illustrated by Bill Peet has to be broken

into a number of short scenes cutting back past the elephants.

14b

14b

This makes animation easier to do and, consequently, fewer drawings.

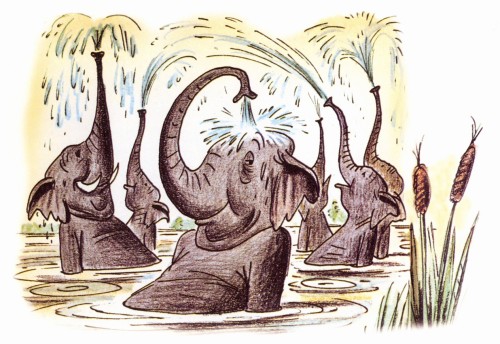

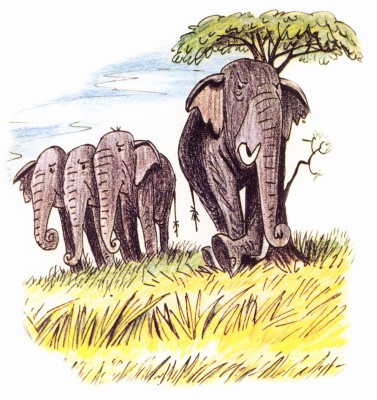

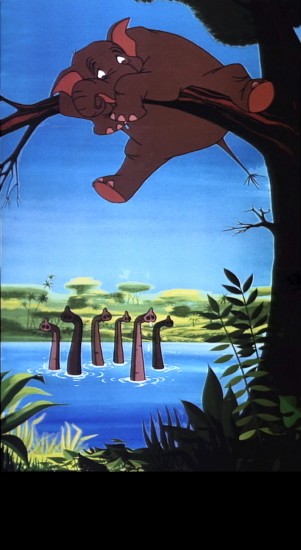

15a

15a

The elephants end up in water, but they jump in

one at a time. Better for the reuse of animation.

16

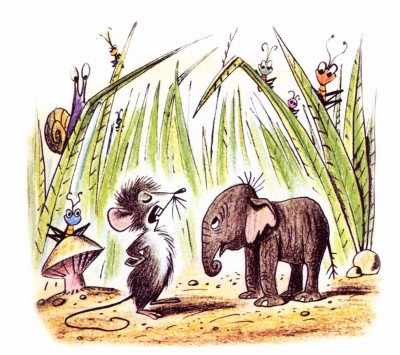

16

The mouse enters the story.

17a

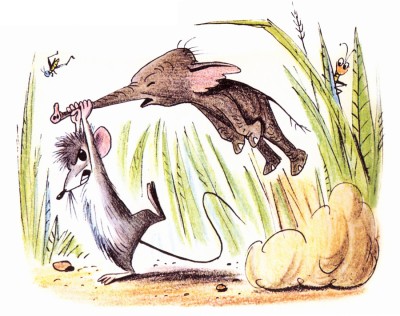

17a

The mouse throws Goliath in a very different way.

17b

17b

Unfortunately they’ve plotted the entire move

with an overlay that cuts up part of the action.

Commentary 02 Apr 2011 08:23 am

Dilworth and 100 Features and Thursday

The Dirty Birdy

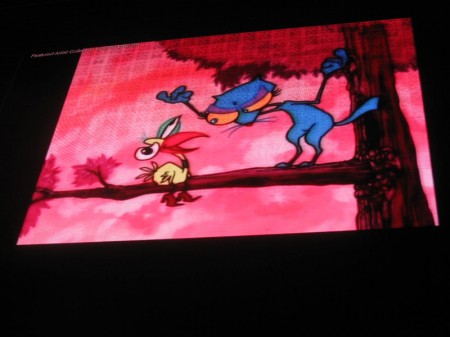

- Last night was John Dilworth night at the Big Screen Project. As you can see from the above photo, this is a 30 foot video screen plunked mid block off Sixth Avenue between 29th & 30th Streets. John invited lots of friends for the two screenings. Unfortunately, the weather didn’t cooperate, and we had a cool, windy, rainy night.

The event, however, wasn’t spoiled because there was an enclosure into the building, and we were able to look out at the monitor. They hand out closed circuit radios (with earplugs – you take home with you) to hear the sound track (in stereo) while watching from the warm comfort of the building. It’s a food court so there’s plenty of food to purchase or you can have a drink, since the area we watched from was a pub. It made for a fun and interesting experience.

The program was well organized and coordinated by Jaime Ekkens for Big Screen Project.

Looking out to the screen from the bar.

The films absolutely seemed to glow on the crystal clear monitor.

There are plenty of other animators up this April to showcase their films. Go here to see the April schedule. Emily Hubley‘s films are up next on April 11th.

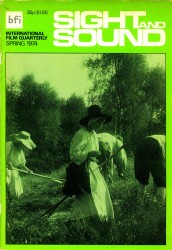

- This past week I received a book in the mail, 100 Animated Feature Films. When the book arrived, I was so taken by the cover design (an image from Lotte Reiniger‘s Prince Achmed, the first full length animated feature) that I immediately opened and started into the book.

- This past week I received a book in the mail, 100 Animated Feature Films. When the book arrived, I was so taken by the cover design (an image from Lotte Reiniger‘s Prince Achmed, the first full length animated feature) that I immediately opened and started into the book.

I was curious about the taste of the author, Andrew Osmond. Would it be another list that would be more studio oriented or more, perhaps, something a bit more siding with the Independent studio. Would his taste run more to the current films or the Golden Age? He’s written a number of articles about Satoshi Kon and Miyazaki for Britain’s The Guardian, so one has a good idea of his preferences.

In fact, I found myself pretty well pleased with a lot of the listings. It’s a bit more Anime than I would have gone toward, but I can easily understand the choice. However, there are many expected and deserved choices within the book. I’m glad to see Reininger’s Prince Achmed listed, as, of course, is Snow White. Other Disney titles include: Pinocchio, Bambi, Fantasia, Dumbo, Beauty and the Beast. There are also a bunch of Pixar films, some of which are: only one Toy Story (the original), The Incredibles, Monsters Inc., Finding Nemo and Up.

In fact, I found myself pretty well pleased with a lot of the listings. It’s a bit more Anime than I would have gone toward, but I can easily understand the choice. However, there are many expected and deserved choices within the book. I’m glad to see Reininger’s Prince Achmed listed, as, of course, is Snow White. Other Disney titles include: Pinocchio, Bambi, Fantasia, Dumbo, Beauty and the Beast. There are also a bunch of Pixar films, some of which are: only one Toy Story (the original), The Incredibles, Monsters Inc., Finding Nemo and Up.

Surprises were finding some titles such as:

The Thief and the Cobbler. The final film version of Richard Williams’ feature, on the market, is horrible. The one in the works for 30 years was visually stunning. This is listed here for what it might have been.

The Thief and the Cobbler. The final film version of Richard Williams’ feature, on the market, is horrible. The one in the works for 30 years was visually stunning. This is listed here for what it might have been.Sita Sings the Blues. This is the only Flash animated feature included. A truly solo work, Nina Paley, created a thinking film with a lot of glorious sections.

Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker. This is a spin-off the television series, and doesn’t have the weight that any title in such a book deserves.

A Scanner Darkly. I might have chosen Waking Life over this title, but I suppose this has a more coherent story. Regardless, I’m glad to see one of Richard Linklater’s films included.

Avatar. Jim Cameron fought to make sure people didn’t consider this animation. I guess, he’s lost. Animation or Live Action, it’s not a very good film.

Both of Sylvain Chomet‘s films: The Illusionist and The Triplettes of Belleville. They both belong here.

Surprises not found in the book:

Gulliver’s Travels. Osmond includes Hoppity Goes to Town, but leaves Gulliver out. Excuse me, but Batman Beyond OVER the beautiful Fleischer gem? Something doesn’t smell so good.

Gulliver’s Travels. Osmond includes Hoppity Goes to Town, but leaves Gulliver out. Excuse me, but Batman Beyond OVER the beautiful Fleischer gem? Something doesn’t smell so good.Ratatouille. This is certainly one of the best of Pixar’s films. To include Finding Nemo and not this excellent feature by Brad Bird is just crazy. I suppose he had Bird’s The Incredibles and he wanted to write about Andrew Stanton.

And if you’re going to include films for the sake of the director, wouldn’t Chuck Jones‘ only feature, The Phantom Tollbooth, be included?

Neither UPA feature: Magoo’s 1001 Arabian Nights and Gay Purr-ee were both left out of the book. Given the heavy number of Japanese features, I would have found one to keep out to include a UPA example.

However despite any gripes, I have to say the book is solidly written and intelligently put together with a lot of thought going into the choices. It’s expected I’d have opposing thoughts on the titles included, but I admit to being intelligently challenged by the author. Andrew Osmond did a fine job, and the book is graphically attractive. I do wish, though, that the type were a bit larger. It looks like it’s about 8pt. and it’s too small for my aging eyes. The book was published by BFI Screen Guides.

However despite any gripes, I have to say the book is solidly written and intelligently put together with a lot of thought going into the choices. It’s expected I’d have opposing thoughts on the titles included, but I admit to being intelligently challenged by the author. Andrew Osmond did a fine job, and the book is graphically attractive. I do wish, though, that the type were a bit larger. It looks like it’s about 8pt. and it’s too small for my aging eyes. The book was published by BFI Screen Guides.

The images above can be found in the book.

1) Animal Farm

2) 101 Dalmatians

3) The Yellow Submarine

4) Ivan and His Magic Pony

5) The Tale of the Fox

I saw this film on line last Tuesday. Cartoon Brew posted it on Wedneday. If you saw it there, I’m pleased; if not this is for you. Matthias Hoegg‘s BAFTA nominated short, Thursday, can be seen online here. It’s an excellent film with a lot of the character necessarily developed through the animation. At the same website, there’s also an interview with Matthias about the making of the short. Take the 7 minutes to watch the film. A good use of cgi and 2D.

He’s represented by Beakus. Their site also showcases a number of his films.

Articles on Animation &Disney &Fleischer 07 Dec 2010 09:19 am

Life after Pearl Harbor

- Today marks the anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This was not only a disastrous day for our country, and whatever affects our country affects the animation studios equally.

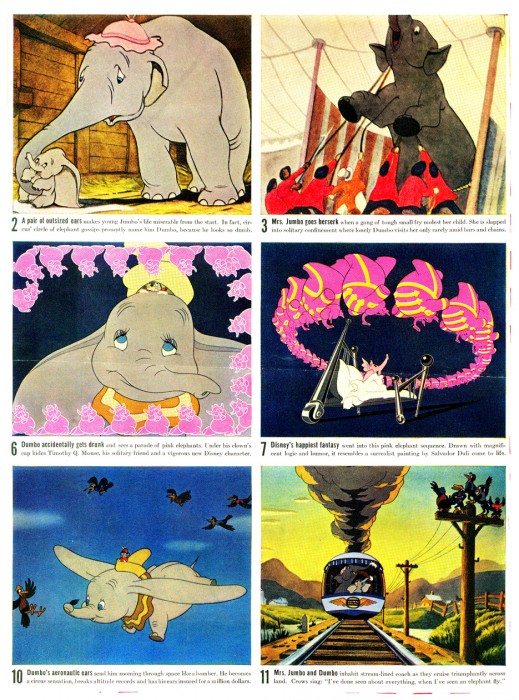

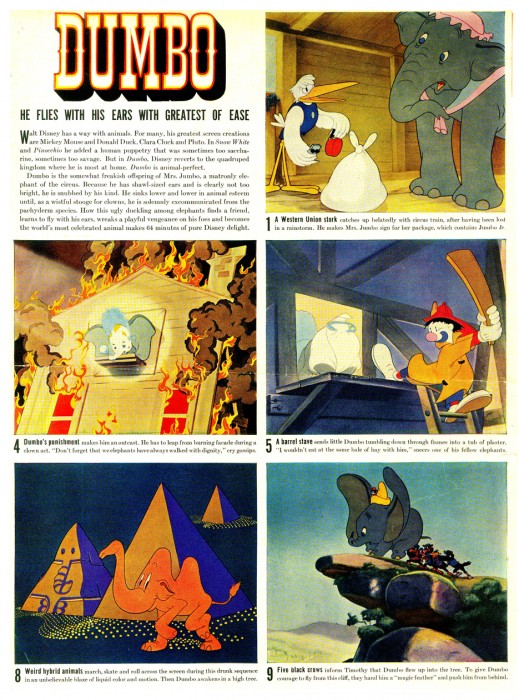

The December 8, 1941 issue of LIFE Magazine included this display of DUMBO stills. A day after the bombing, I kind of suspect no one was into noticing the stills. George MacArthur was on the magazine’s cover – not intentionally bringing War into the issue, but accidentally doing it.

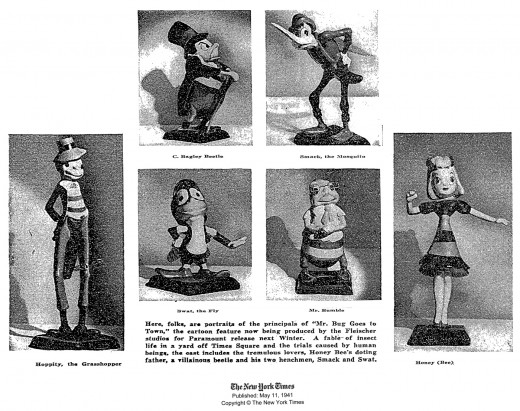

Fleischer’s Hoppity Goes To Town had the same sad problem. It opened the week after Pearl Harbor and sank as quickly as the Hawaiian Fleet. The film was finally reviewed in the NY Times in February 1942 (as can be read below) but there wasn’t much to save it at the box office.

Here’s a promotion that ran in the NYTimes in May of 1941,

six months before the film would be released to a deadened market.

Articles on Animation &Commentary &Daily post &Miyazaki 04 Dec 2010 09:53 am

Grab-bag

- There’s a wonderful new blog post on Darrell Van Citters’ Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol blog. It features the story of Abe Levitow as told by his children, “REMEMBERING THE MOOSE†by Judy, Roberta and Jon Levitow. A great piece to read, I encourage you all to take a look.

- There’s a wonderful new blog post on Darrell Van Citters’ Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol blog. It features the story of Abe Levitow as told by his children, “REMEMBERING THE MOOSE†by Judy, Roberta and Jon Levitow. A great piece to read, I encourage you all to take a look.

This is a great site, by the way. Plenty of material about the artists who were involved in those changeover days at UPA. Great artists get their due, lots of artwork from the film and the period, and lots of info to learn.

- According to Variety, Disney has picked up the distribution rights for the Spanish animated feature, Chico and Rita. This is director/producer, Fernando Trueba‘s first attempt at directing an animated film. Spanish graphic artist, Javier Mariscal, co-directed the film.

- According to Variety, Disney has picked up the distribution rights for the Spanish animated feature, Chico and Rita. This is director/producer, Fernando Trueba‘s first attempt at directing an animated film. Spanish graphic artist, Javier Mariscal, co-directed the film.

The film celebrates the Cuban jazz pianist, Chico, and his relationship with nightclub singer, Rita, as they leave Cuba to move to the jazz world of the New York in the late 40s.

Disney will release Chico and Rita Feb. 25 on more than 100 screens. (This, of course will allow Disney to enter it into next year’s Oscar fest. in an attempt to get the number up to 16 for a five nominee ballot.)

The film won for best feature at the Holland Animation Film Festival in November. The animated movie continues Trueba’s taste for Latin music, already reflected in three awarded musical docus (“Calle 54,” “Blanco y negro” and “The Miracle of Candeal”) and the creation of a Latin jazz record label.

It’s unlikely they’re expecting a wealth of cash from the distribution of the film except, perhaps, making something from the DVD, if it gets good reviews. I notice that they haven’t picked up the TV rights.

– Meanwhile, writer/director, Geoff Marslett’s animated feature, Mars, opened in New York

yesterday. The NYTimes review by Jeannette Catsoulis wasn’t all that it might have been. She called it “. . . low key, low budget and low energy . . .” and pretty much left it at that. The film is another of those rotoscoped-animation type things not quite as energetic as “Waking Life†and “A Scanner Darkly.â€

yesterday. The NYTimes review by Jeannette Catsoulis wasn’t all that it might have been. She called it “. . . low key, low budget and low energy . . .” and pretty much left it at that. The film is another of those rotoscoped-animation type things not quite as energetic as “Waking Life†and “A Scanner Darkly.â€

Marslett, who teaches animation at the University of Texas at Austin. The film is playing at: the reRun Gastropub Theater, 147 Front Street, Dumbo, Brooklyn.

- William Benzon, again, has written several excellent pieces on animated films on the blog New Savannah. He has a two part article on Miyazaki‘s film Porko Rosso. The article intelligently argues the idea of a pig, the leading character, being the only non-human in a particular world where no one takes notice. Part 1 and Part 2.

There’s also a third recent article on thoughts generated by Miyazaki in his book, Starting Point, about how he constructs his films with an ever changing and growing storyboard that doesn’t get done until the film is, usually, already being animated. Go here to read this piece.

- I received a letter, accompanied by a Press Release, from Don Hahn re the video release of his documentary, Waking Sleeping Beauty. Here’s part of the email letterL

- I received a letter, accompanied by a Press Release, from Don Hahn re the video release of his documentary, Waking Sleeping Beauty. Here’s part of the email letterL

- After a yearlong trek though film festivals and art house cinemas, my documentary WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY is coming out on DVD this week and I hope you’ll get a chance to review it. WSB tracks the renaissance of Disney Animation from box office disappointments and the near closure of the studio, to great success with films like The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King.

The positive response to the film has been bigger than I ever imagined. Not only has it appealed to the fans of animation, it’s also struck a chord with corporations and organizations of all kinds that have gone through their own periods of declines and resurrections. We found that WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY not only entertained, but touched people emotionally as well.

The DVD has over 80 minutes of bonus material with amazing footage of Howard Ashman working with Jodi Benson during the recording sessions for The Little Mermaid and Howard’s priceless talk to the animation crew about musical theater and animation. I also put together an audio commentary track that features alternate narration from Peter Schneider and myself as well as new unheard material from Glen Keane, Mike Gabriel, Kirk Wise, Rob Minkoff, Jeffrey Katzenberg and Roy Disney.

I hope you’ll get a chance to view the doc and announce to your readers that WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY is out on DVD tomorrow, November 30th.

I wrote about this film and reviewed it when it was released theatrically back in March of this year. You can read that here.

Commentary 30 Oct 2010 07:43 am

Bits

- They’ll need 16 animated features entered into the competition for the MP Academy to select five films for Oscar contention. To date, according to Nikki Finke‘s column, there have been only 14 – meaning a choice of three titles for the Award. Producers have until Monday, Nov. 1st to get a film entered.

- They’ll need 16 animated features entered into the competition for the MP Academy to select five films for Oscar contention. To date, according to Nikki Finke‘s column, there have been only 14 – meaning a choice of three titles for the Award. Producers have until Monday, Nov. 1st to get a film entered.

So far these have been entered:

Pixar’s Toy Story 3

Dreamworks’ How To Train Your Dragon

Disney’s Tangled

Dreamworks’ Megamind

Despicable Me

The Illusionist

Zack Snyder’s Legend Of The Guardians: The Owls Of Ga’Hoole

WB’s live action/ani combo’d Yogi Bear

DreamWorks’ Shreak Forever After

Bill Plympton’s Idiots And Angels

the Japanese anime, Summer Wars

Lions Gate’s Alpha And Omega

Tinker Bell & The Great Fairy Rescue

Paul & Sandra Fierlinger’s My Dog Tulip

The first two films, Toy Story 3 and How To Train Your Dragon are both vying for Best Picture as well. Good Luck, in the field of 10 titles.

- Darrel Van Citters‘ blog for Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol is turning into one of my favorite places to visit. Aside from showcasing the excellent book Mr. Van Citters wrote (trust me this should be in your collection if you have any interest in 2D animation and/or UPA), the site focusses on many of the artists who worked on the UPA TV special.

The intro to Sherman & Peabody by Shirley Silvey.

Recently Shirley Silvey‘s career was highlighted in a great piece. Here’s a brilliant artist whose work has been pretty-much ignored by the animation community, and it’s great to see her get a little of her due attention. The same can be said about other artists who have been featured on this site: Tony Rivera, Phil Norman or Bob Inman.

Van Citters has also been running a four-part series about the takeover of UPA from Stephen Bosustow by Hank Saperstein and his company, Television Personalities. Immediately, The Mr. Magoo Show, The Dick Tracy Show, and other product went into production and on the market.

Take a look at the site.

- I’m sad to see the passing of James MacArthur. He was the adopted son of actress, Helen Hayes, and starred in so many of those wonderful Disney live-action films of the late fifties, early sixties.

How clearly do I remember sitting through Third Man on the Mountain many times so that I could get to see Snow White again. Back then, there was no video tape/no DVD. Films ran in theaters on double-bills (two films for the price of one), and you had to get through the dud to see the one you wanted to see. I was there – many times – to see Snow White, but Third Man was always running when I got into the theater. However, I saw Third Man so many times I got to like it as well.

James MacArthur was a big part of that experience. He was also in these Disney films:

The Swiss Family Robinson, Kidnapped, and The Light in the Forest.

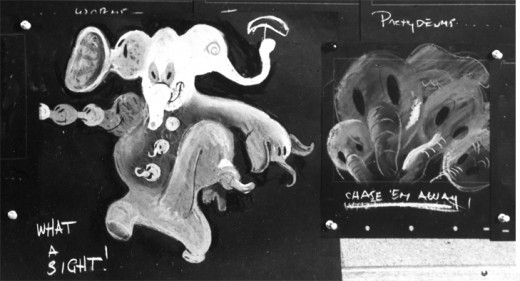

Bill Benzon has another excellent piece on his blog, New Savanna. This is an analysis of the Pink Elephants on Parade sequence from Dumbo.

Called Secrets of Pink Elephants Revealed, it, like all of Bill Benzon’s writing, deserves to be noticed and read.

Take a look.

Articles on Animation &Richard Williams 26 Oct 2010 07:58 am

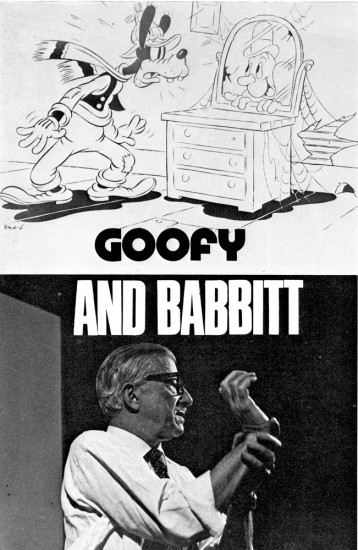

Goofy and Babbitt

- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

You can see the film on YouTube, here.

I previously posted the first half of this article with all the Goofy model sheets that it accompanied. You can see that here.

(The original, unfortunately, contains the “N” word instead of “coloured boy” as this edited version offers.)

.

Goofy and Babbitt

by Art Babbitt and Richard Williams

.

Two of the great artist-animators of the golden years of the Disney Studios, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick, were working and teaching at the Richard Williams Studios in London last summer. To parallel Babbitt’s 1934 character analysis of Goofy, which has not previously been published, Richard Williams gives an impression of the animator himself.

Two of the great artist-animators of the golden years of the Disney Studios, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick, were working and teaching at the Richard Williams Studios in London last summer. To parallel Babbitt’s 1934 character analysis of Goofy, which has not previously been published, Richard Williams gives an impression of the animator himself.

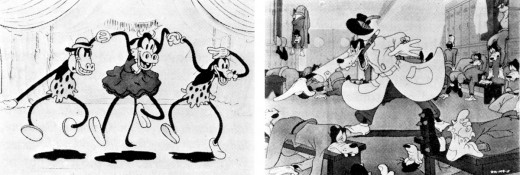

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE GOOF—JUNE 1934

In my opinion the Goof, hitherto, has been a weak cartoon character because both his physical and mental make-up were indefinite and intangible. His figure was a distortion, not a caricature, and if he was supposed to have a mind or personality, he certainly was never given sufficient opportunity to display it. Just as any actor must thoroughly analyse the character he is interpreting, to know the special way that character would walk, wiggle his fingers, frown or break into a laugh, just so must the animator know the character he is putting through the paces. In the case of the Goof, the only characteristic which formerly identified itself with him was his voice. No effort was made to endow him with appropriate business to do, a set of mannerisms or a mental attitude.

It is difficult to classify the characteristics of the Goof into columns of the physical and mental, because they interweave, reflect and enhance one another. Therefore, it will probably be best to mention everything all at once.

Think of the Goof as a composite of an everlasting optimist, a gullible Good Samaritan, a half-wit, a shiftless, good-natured coloured boy and a hick. He is loose-jointed and gangly, but not rubbery. He can move fast if he has to, but would rather avoid any over-exertion, so he takes what seems the easiest way. He is a philosopher of the barber shop variety. No matter what happens, he accepts it finally as being for the best or at least amusing. He is willing to help anyone and offers his assistance even where he is not needed and just creates confusion. He very seldom, if ever, reaches his objective or completes what he has started. His brain being rather vapoury, it is difficult for him to concentrate on any one subject. Any little distraction can throw him off his train of thought and it is extremely difficult for the Goof to keep to his purpose.

Yet the Goof is not the type of half-wit that is to be pitied. He doesn’t dribble, drool or shriek. He is a good-natured, dumb bell what thinks he is pretty smart. He laughs at his own jokes because he can’t understand any others. If he is a victim of a catastrophe, he makes the best of it immediately and his chagrin or anger melts very quickly into a broad grin. If he does something particularly stupid he is ready to laugh at himself after it all finally dawns on him. He is very courteous and apologetic and his faux pas embarrass him, but he tries to laugh off his errors. He has music in his heart even though it be the same tune forever, and I see him humming to himself while working or thinking. He talks to himself because it is easier for him to know what he is thinking if he hears it first.

His posture is nil. His back arches the wrong way and his little stomach protrudes. His head, stomach and knees lead his body. His neck is quite long and scrawny. His knees sag and his feet are large and flat. He walks on his heels and his toes turn up. His shoulders are narrow and slope rapidly, giving the upper part of his body a thinness and making his arms seem long and heavy, though actually not drawn that way. His hands are very sensitive and expressive and though his gestures are broad, they should still reflect the gentleman. His shoes and feet are not the traditional cartoon dough feet. His arches collapsed long ago and his shoes should have a very definite character.

Never think of the Goof as a sausage with rubber hose attachments. Though he is very flexible and floppy, his body still has a solidity and weight. The looseness in his arms and legs should be achieved through a succession of breaks in the joints rather than through what seems like the waving of so much rope. He is not muscular and yet he has the strength and stamina of a very wiry person. His clothes are misfits, his trousers are baggy at the knees and the pant legs strive vainly to touch his shoe tops, but never do. His pants droop at the seat and stretch tightly across some distance below the crotch. His sweater fits him snugly except for the neck, and his vest is much too small. His hat is of a soft material and animates a little bit.

It is true that there is a vague similarity in the construction of the Goof’s head and Pluto’s. The use of the eyes, mouth and ears are entirely different. One is dog, the other human. The Goof’s head can be thought of in terms of a caricature of a person with a pointed dome—large, dreamy eyes, buck teeth and weak chin, a large mouth, a thick lower lip, a fat tongue and a

bulbous nose that grows larger on its way out and turns up. His eyes should remain partly closed to help give him a stupid, sloppy appearance, as though he were constantly straining to remain awake, but of course they can open wide for expressions or accents. He blinks quite a bit. His ears for the most part are just trailing appendages and are not used in the same way as Pluto’s ears except for rare expressions. His brow is heavy and breaks the circle that outlines his skull.

He is very bashful, yet when something very stupid has befallen him, he mugs the camera like an amateur actor with relatives in the audience, trying to cover up his embarrassment by making faces and signalling to them.

He is in close contact with sprites, goblins, fairies and other such fantasia. Each object or piece of mechanism which to us is lifeless, has a soul and personality in the mind of the Goof. The improbable becomes real where the Goof is concerned.

He has marvelous muscular control of his bottom. He can do numerous little flourishes with it and his bottom should be used whenever there is an opportunity to emphasise a funny position.

This little analysis has covered the Goof from top to toes, and having come to his end, I end.

ART BABBITT

.

‘Orphans’ Benefit’ (1934). The Goof after Babbitt: ‘How to Play Football’ (1944)

.

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE ANIMATOR—JANUARY 1974

.

He is a funny mixture. He has the bearing of a Marines sergeant (which he was during the war, after leaving Disney following the strike in which he was the principal figure); but he has the mind of a Viennese doctor—which is what he wanted to be. In his youth he always wanted to go to Vienna and study psychiatry; but he couldn’t because he was a poor boy from Iowa with relatives to support. So he went to New York and taught himself to be a commercial artist; and gradually got into animation—starting, I think, through Paul Terry.

Arriving at Disney, he was one of four animators on Three Little Pigs; and of course that was the great breakthrough in personality animation. Then he animated Goofy, and worked on shorts in preparation for Snow White. In the first Disney feature he animated the Queen where she was beautiful, up to the point where she is transformed into the hag. In Pinocchio he did most of the animation of Gepetto, and Gepetto almost looks like him. He had that sort of versatility, to characterise the horrid queen or the sentimental wood-carver. Then in Fantasia he did primarily the mushroom dance; but he was animation director on a lot of other material. On Dumbo he was a supervising animator.

The strike came in 1941. Babbitt had had a personal confrontation with Disney over the low payment of assistants; and Disney ill-advisedly fired him, giving as a reason his u-nion activities. This was directly in contravention of the Wagner Labor Relations Act, and the

U-nion took a strike vote. Babbitt fought Disney through all the courts; and they were obliged to reinstate him, for an uncomfortable period during which Disney would pass him in the corridor without speaking or even looking at him. He stood it for a year; then he quit.

After the war he and Natwick were with Hubley at UPA – Art did most of Rooty Toot Toot. Later he was with Hanna and Barbera. I had heard about him for years before I finally came to meet him. He had seen some of our work, and though he’d not exactly liked it (it was pretty slick) had decided that ‘here are some people trying to do an honest job, and that’s the first time I’ve seen that in ten years.’ He wasn’t all that impressed, but he went to the heart of it.

It turned out he was very interested in teaching people. He was thinking of writing a book to instruct people; and he’d done a course at U.S.C. of which we had copies of students’ notes. As it happened he had a fire at his house and all his own lecture notes were burned. So we were able to send him these student notes. He said they were all wrong; but it was something. Then finally I asked him straight out if he would come over and teach us, because we had gone as far as we could go on our own.

He is a great teacher. He has an astonishing lucidity. Most animators are completely incoherent; they are unable to tell you what they are doing. But Art doesn’t have any difficulty in showing you how a thing works. He just says: ‘Did you notice that that worked because such and such . . . and Hubley did this thing this way?’ And when Art says something is wrong, he’s invariably right—if you want it to work. He’ll say: ‘If you want the wheel to go round, this is the way to make it go round. This is the way to make a cypher for making it go round. And this is another way they used to give the impression of it going round. And your problem is that you are to do it with square wheels.’ He is completely eloquent. I’m sure that at Disney they created a language about what they were doing; and I’m equally certain that it was he who largely gave a verbal form to it, so that the others could understand it. He has a surgeon’s mind; which, I gather, Disney had also.

When he taught in our studio he insisted that people take the course. He started off by saying: ‘Please, in my lectures, do not be British. Be crude, be revolting; ask stupid questions. Please do not be polite; otherwise I’m wasting my time.’ He’s as tough as nails; yet it literally hurt him when someone couldn’t get a thing right, couldn’t understand it. Then when they got it right, he would dissolve in warmth. His patience was beautiful.

He knows so much about everything— about symphony construction, about the visual arts, about everything to do with the medium. He once decided he would teach himself to play the piano. He’s the one in the famous Disney story —when he was learning to play the piano, and Disney said, ‘What are you—some kind of fag or something ?’ He hated Disney for that, because he wanted to understand music to apply it to animation. He knew that Fantasia or something like it was inevitable.

On the course he told us: ‘An animator must possess a curiosity about everything that exists or moves . . . must be a student of everything that might or does exist. From the shiver of a blade of grass—affected by an invisible breeze—to the behaviour of a starving hobo eating the first steak he has had in years. From a baby, tentatively trying to walk for the first time—to an elephant doing the can-can.’

I just saw Fantasia again and the Dance of the Mushrooms; and he was doing things there—treating perspective as a subsidiary action—that no one else was doing at the time. And he does not do it by feel, as I might, but because he’s worked it all out and analysed it. On the course he would say: ‘This is the cliché. This is the formula. And this is how to break it.’ He would set up the rules and then make you bust them.

And as well as the analytical capacity and the intelligence is the ability to start from basics—to deal with the most minute detail. He knows how the labs process the material; the way celluloid is made, the way the pencil is made. People who know that kind of thing don’t usually have artistic ability into the bargain. The ability to discern basics extends to his gift for statements that seem entirely simple and yet reveal vital things one often has not recognized : ‘We must learn to create movements if necessary that are caricatures of reality— but done with such guile they are always convincing.’ ‘We must expand our sense of caricature—to realise that we are not simply exaggerating external appearances— but more important, the inner character, the mood, the situation. A caricature is a satirical essay, not just doubling the size of a bulbous nose.’

A Babbitt scene from Williams’ Cobbler and the Thief.

My portrait is idolatry, maybe; but how do you not idolize someone who after more than forty years work in his and your medium still can find it ‘wonderful, exciting, exacting … A medium that has barely been discovered, let alone explored. A medium that can be an art form that encompasses practically all other art forms. A medium that can gratify aesthetically, that is not earth-bound, that can be an invaluable aid in teaching everything from elementary chemistry to the Theory of Relativity.’

RICHARD WILLIAMS

Animation &Articles on Animation &Disney 22 Oct 2010 07:46 am

Oskar Fischinger at Disney

The following article appeared in the 1977 Anmation Issue of MILLIMETER MAGAZINE as edited by John Canemaker. (Some of those commercial magazines were just excellent back then, and we never seemed to notice or properly appreciate them.)

or, Oskar in the Mousetrap

by William Moritz

Oskar Fischinger at work at the Walt Disney Studio in 1939

Courtesy of Mrs. Elfriede Fischinger, all rights reserved

The official Disney account of the origin and making of FANTASIA has been told many times — from the early press releases, programs, and Feild’s wide-eyed, idolatrous book from 1942, THE ART OF WALT DISNEY (all united by the “official studio policy”/ mannerism of discussing primarily Walt Disney himself as if he had conceived and designed the films almost single-handedly), down to the more reasonable, carefully-researched materials published recently, such as the article by Disney archivist David R. Smith for MILLIMETER’S 1976 animation issue, and Bob Thomas’ new biography, WALT DISNEY, AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL.

I have already given an outline of another side to this story in my bio-filmo-graphy of Oskar Fischinger (FILM CULTURE 58-59-60-, 1974, pp. 61-65), but Fischinger’s tale bears re-telling since clearly a full understanding of the matter lies in discovering all that went on behind the scenes and in Fischinger’s heart-of-hearts.

Oskar Fischinger, who was a year older than Walt Disney, devoted his major energies throughout his life to abstract animation. In the early Twenties, while the Disney brothers assembled Ub Iwerks and a remarkable collection of talents to form an animation studio for production of Alice and Oswald cartoons, Fischinger, working on his own, struggled with radical experiments in non-objective imagery — from sliced wax to multiple-projector light shows. Even before sound film became available, Fischinger synchronized his abstract films to phonograph records and live musical accompaniments, because he found that the analogy with music (i.e., abstract noise well-developed and widely-accepted non-objective art form) helped audiences to grasp and accept the nature and meaning of his “universal”, absolute imagery. Oskar never meant to illustrate music, and often screened his “sound” films silently for already sympathetic audiences.

At the same time Iwerks/Disney’s Mickey Mouse and SILLY SYMPHONIES (and clever mass-marketing techniques) began to gain world-wide acclaim for the Disney Studios, Fischinger also enjoyed a moderate international renown as well, with his black-and-white STUDIES playing as novelty shorts with features from Uruguay to Japan. And while Disney began to win Academy Awards for his shorts, Fischinger also won grand prizes at film festivals in Brussels and Venice.

By 1935, Fischinger had made at least 35 abstract animated shorts, and stated as his New Year’s wish in the Berlin trade paper FILM KURIER that he wanted most to create an animated feature composed entirely of non-objective imagery and diverse music (he had used jazz, toyed with experimental electronic music and his own synthetic drawn soundtracks as well as classical music).

A scene from Walt Disney’s FANTASIA (1940)

Unfortunately for Fischinger, political events militated against him for much of his life, but he still produced a body of work that plays increasingly in theatres and museums as several full-evening programs.

The Nazi government had banned abstract art as degenerate, and was officially outraged that Fischinger’s COMPOSITION IN BLUE won festival prizes. Oskar in turn happily accepted a contract with Paramount and sailed for Hollywood in February, 1936, never to return to Germany. Unfortunately he spoke no English and encountered tremendous, frustrating difficulties in his early studio jobs. He assumed Paramount wanted him to pursue the style of his prize-winning COMPOSITION IN BLUE, but instead they wanted more representation and cuter work like his Muratti cigarette commercials. After he had completely painted and photographed a color abstract sequence (later called ALLEGRETTO), the director Mitchell Leisen insisted the piece be re-done in black-and-white with representational images of musical instruments and other pop trick effects overlayed. The resulting studio version disgusted Fischinger and he quit Paramount only half-a-year after he started there.

His second American film, AN OPTICAL POEM, made for MGM under William Dieterle’s aegis, proved one of Oskar’s finest works, and though not exactly a box-office sensation, played prestige bookings with first-run features, and was mentioned by one critic as a likely Oscar nominee (which caused Fischinger to quip, “Why bother giving me Oscar? I am Oskar!”).

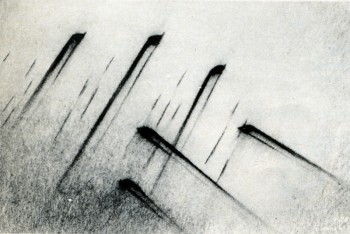

A Fischinger pencil sketch (with numerical

motion-phase breakdowns) for “Toccata and

Fugue” section of Disney’s FANTASIA.

After his MGM option was not picked up, Fischinger drove to Detroit and New York seeking backing for a feature-length animated film based on Dvorak’s “NEW WORLD” SYMPHONY, which he hoped to be able to present at the World’s Fair. Although this project never materialized, Oskar dallied in New York because he discovered a new ambiance there: unlike Hollywood, he was treated as a major artist in New York, invited to screen his films and exhibit paintings, dine with leading filmmakers, critics and painters, spend weekends at the country estate of Guggenheim Foundation curator Hilla Rebay. He returned to Hollywood only when his agent cabled that he had a job for him at Disney.

What a rude shock Fischinger received upon his return! Already in Berlin, Oskar had been attracted to Leopold Stokow-ski’s grand orchestral arrangements of Bach and had tried to get music rights to some of his pieces. When Fischinger found that Stokowski was his co-worker at Paramount, he once again proposed a series of shorts or an anthology feature. Stokowski was initially quite receptive and wrote Fischinger (October 9, 1936, on Paramount stationery), “I should be very happy if we could work together — you doing what is seen, I doing what is heard.” And he received from Fischinger such elaborate ideas as (November 15, 1936, in German):

“If you are here at Christmas, I’d like to make a full-length shot of you in such a way that the visual part of the film could begin with you conducting the first few bars of the music, and then the eyes of the viewer would glide with a movement of your hands off into endless space where the rest of the visuals would unfold. ”

Nevertheless, after several conferences, Stokowski decided that the project would be too expensive and complex for Oskar to animate alone, and suggested that they seek support from a major studio, perhaps Disney. Fischinger held little hope for satisfactory help from Hollywood, especially after his experiences, and furthermore he knew from gossip that Disney, despite his successes, was under severe strain, borrowed and mortgaged to the hilt. And Oskar’s worst fears were seemingly confirmed when he returned to Hollywood in November, 1938, to find that while Stokowski was being honored as Disney’s major collaborator on “The Concert Feature”, Fischinger was being hired for $60-per-week (Paramount had paid him $250) as a “Motion picture cartoon effects animator”.

Fischinger accepted the job since work was scarce and he had four children to support, but for him the Disney episode proved a nightmare which so angered him that he conspicuously avoided talking about it in later years. Only once did he write a note on his Disney adventure (in a letter to a friend), and it expressed well his chagrin:

“I worked on this film for nine months; then through some “behind the back” talks and intrigue (something very big at the Disney Studios) I was demoted to an entirely different department, and three months later I left Disney again, agreeing to call off the contract. The film “Toccata and Fugue by Bach” is really not my work, though my work may be present at some points; rather it is the most inartistic product of a factory. Many people worked on it, and whenever I put out an idea or suggestion for this film, it was immediately cut to pieces and killed, or often it took two, three or more months until a suggestion took hold in the minds of some people connected with it who had their say. One thing I definitely found out: that no true work of art can be made with that procedure used in the Disney Studio.”

At first, Fischinger threw himself whole-heartedly and good-naturedly into the project. He gave prints of his films to be screened weekly for the entire Disney staff, so his influence was pervasive (spilling over onto other films like DUMBO, the South American films, and PINOCCHIO, for which Oskar actually animated the magic wand of the Blue Fairy). In the mimeographed transcript of the story meeting for February 28, 1939, Walt Disney says (p. 1): “Everything that has been done in the past on this kind of stuff has been cubes, and different shapes moving around to the music. It has been fascinating. From the experience we have had here with our crowd — they went crazy about it. If we can go a little further here and get some clever designs, the thing will be a great hit. I would like to see it sort of near-abstract, as they call it — not pure. And new.”

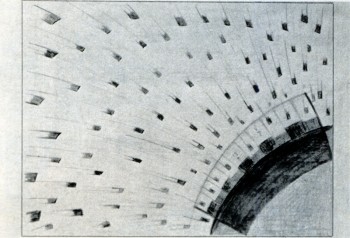

Fischinger’s numerical motion-phase breakdown

for “the Wave” scene in “Toccata and Fugue”

section of FANTASIA.

© Fischinger Trust, all rights reserved.

Perhaps because of the uneasy proximity of Fischinger, Walt exhibits a certain suspiciousness about abstraction, accompanied by a rather defensive attitude towards the prospective audience.

January 24, 1939, p. 2:

Walt Disney: You should give something that the audience will recognize. I don’t think the average audience will fully appreciate the abstract; but I may all be wrong —

Stokowski: Yes, they may be way ahead of us.

or, January 24, 1939, p. 7:

Walt Disney: What will Bach lovers think of this?

Stokowski: They will be against it, I think; but the public will love it.

Walt Disney: Well, the general idea here looks good to me. I only wonder if we’re going a little too gypsy in the color—

or, February 28, 1939, p. 5:

Walt Disney: If we can get a little connection behind this, the public will take to it. It would be better than some wild abstraction that you can’t get anything out of at all. Right there is where the music sounds most like an organ, so the public decides it represents an organ.

or, February 28, 1939, p. 8:

Walt Disney: Do you think we ought to have pictures in mind through this thing? Then we won’t get a conglomerate mess — an abstraction.

or, JuneS, 1939, p. 1:

Walt Disney: There’s a theory I go on that an audience is always thrilled with something new, but fire too many new things at them and they become restless.

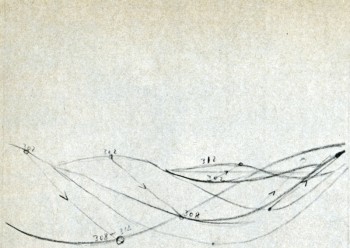

The “wave” scene as it appears in FANTASIA.

©Walt Disney Productions.

Fischinger’s assertions about the unhealthy competitive committee work at Disney would seem to be borne out by the conference notes in which we see during nine month’s of work on the “story” incredible floundering, dreary discussions and re-discussions of each scene, groping and pushing without any controlling factor besides making an entertaining film.

Because he knew little English, Fischinger never spoke up during these story conferences (neither did Kay Nielsen), and further became the butt of endless practical jokes on the part of his jealous co-workers. Some fun-loving boys of the Disney staff, unwilling to deal maturely with the plight of a refugee artist, pinned a swastika on Oskar’s office door September 1, 1939, the day the Nazi armies invaded Poland. Fischinger applied for a release from his contract and after two months of red tape, terminated his employment at Disney, October 31, 1939, Halloween.

Fischinger kept about 100 of his sketches and drawings for the Bach “Fugue”, including some lovely pastels showing melting meanders and supple lozenges much as they appear in the final FANTASIA, as well as half-a-dozen beautiful images that were probably never realized on film. The most extensive unit involves twelve poster-color and 60 pencil drawings (with numerical motion-phase breakdowns) that detail the sequence in which alternating left-and-right-hand “waves” surge toward the viewer. While this turned out to be one of the more impressive moments in the Disney film, a comparison with Oskar’s original sketches shows how much more powerful, subtle and imaginative the sequence might have been if Fischinger’s intentions had been honored — with his choice of monochromatic turquoise and celadon hues for the (somewhat flatter) wave motion overlayed with scintillating geometric figures in browns, Chinese red, and graduated yellow/oranges, all of the elements flowing cogently and vigorously out of each other, as opposed to the simplified Disney image of fat, melon-ribbed waves slightly off-balance in shades of flagrant purple distractingly at constrast in “realism” to the (needlessly) clouded sky behind. All in all, the Disney version of the “Fugue” seems painfully close to the Paramount adulteration of ALLEGRETTO.

Much of Fischinger’s work seems entirely lost. After looking at some of Oskar’s sketches (August 21, 1939, p. 3), Walt Disney comments, “I think the contrast of black and white, and then a little color coming in, would stand out. ” but I don’t think such an effect reached the final version of FANTASIA. Evidently some of Fischinger’s own animation was filmed at least in the pencil test stage, since after viewing some material on a moviola Disney comments (August 21, 1939, p. 7) “Oskarhas a pulsing effect in his test.”

To me, Disney was actually the loser in the matter. Each year Fischinger’s genius and the sincere consistencly of his films becomes more widely acknowledged, while every year the moments of unbearable kitsch, lapses of taste, questionable values, and hodge-podge of stylistics that mar most of the Disney Studio product are becoming more obvious to everyone. For all its considerable virtues of self-parody, rich color and design, etc., FANTASIA falls easily victim to its own shortsightedness so that the burlesque of Bozetto’s ALLEGRO NON TROPPO carries devastating bite.

At least Fischinger had a few of the last laughs in the matter. After leaving the Disney Studios, he devised a set of seven superb collages, among his most charming and highly prized works, showing Mickey and Minnie Mouse (cut from comic books) “reacting” to reproductions of abstract paintings by Kandinsky and Bauer (cut from a 1938 Guggenheim Museum catalogue). And years later, when Disney made the documentary TOMORROW THE MOON, they inadvertantly honored Oskar by using a clip of his pioneer special effects of the rocket launching from Fritz Lang’s FRAU IM MOND, made a quarter of a century earlier.

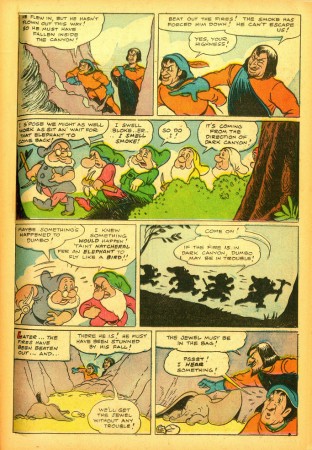

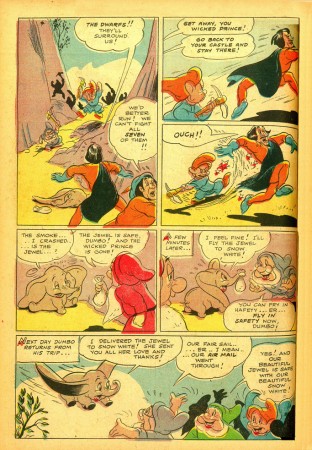

Books &Comic Art &Disney &Illustration 02 Oct 2010 06:34 am

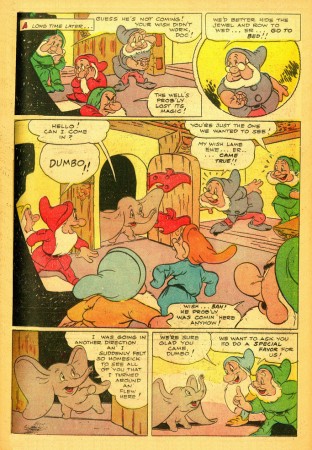

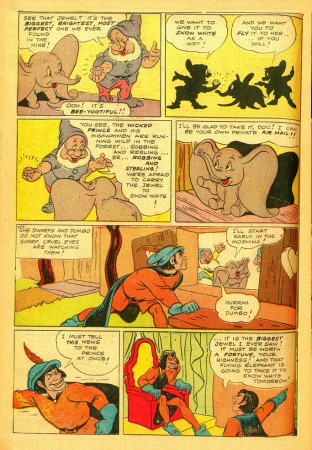

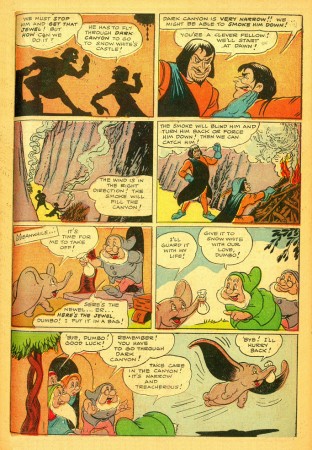

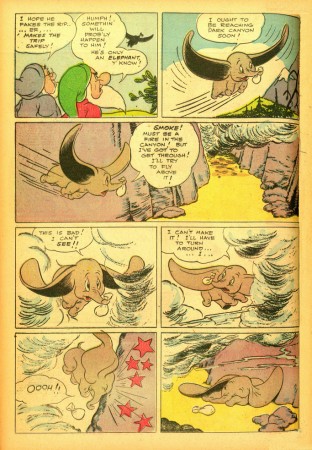

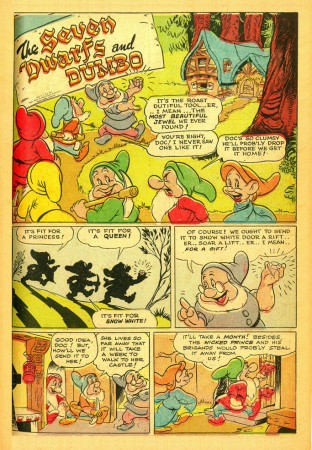

The 7 Dwarfs and Dumbo

.

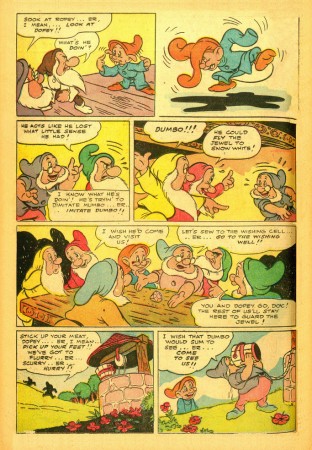

- Here, from Walt Disney Comics, April 1945 edition is a wacky story mixing the Seven Dwarfs with Dumbo to fight the Wicked Prince.

I couldn’t help but post it. These comic books often seem to mix up the characters from different films to create unbelievable stories.

This comic comes from Bill Peckmann‘s enormous collection, and I thank him for sharing, yet again.

.

.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Daily post 01 Oct 2010 05:31 am

Book Signing & SVA Exhibition

Here’s a press release that came from the Museum of Modern Art re a show that John Canemaker will be hosting tonight in celebration of his recent book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft.

- The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters

Academy Award–winning animation filmmaker and author John Canemaker presents an illustrated lecture based on his new book Two Guys Named Joe (Disney Editions, 2010), an immensely entertaining and insightful portrait of the legendary animation storytellers Joe Grant (1908–2005) and Joe Ranft (1960–2005).

Academy Award–winning animation filmmaker and author John Canemaker presents an illustrated lecture based on his new book Two Guys Named Joe (Disney Editions, 2010), an immensely entertaining and insightful portrait of the legendary animation storytellers Joe Grant (1908–2005) and Joe Ranft (1960–2005).

In his long career at Disney, Grant helped create such masterworks as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), Dumbo (1941), Make Mine Music (1946), and Lady and the Tramp (1955), as well as more recent hits like Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Lion King (1994).

Joe Ranft, a Pixar creative cofounder and storyboard artist, is widely celebrated for his imaginative and irreverent contributions to such recent classics as The Brave Little Toaster (1987), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), Toy Story (1995), James and the Giant Peach (1996), Toy Story 2 (1999), Monsters, Inc. (2001), and Cars (2006).

Canemaker will sign copies of his book after the lecture on October 1. On October 2, MoMA pays tribute to these master animation storytellers with a selection of wonderful animated features and shorts—including Fun with Mr. Future (1982), which hasn’t been screened in nearly thirty years, and a special screening of Dumbo (1941).

Canemaker will sign copies of his book after the lecture on October 1. On October 2, MoMA pays tribute to these master animation storytellers with a selection of wonderful animated features and shorts—including Fun with Mr. Future (1982), which hasn’t been screened in nearly thirty years, and a special screening of Dumbo (1941).

The MOMA’s programs for Two Guys Named Joe is organized by Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film. Special thanks to Howard Green and Wendy Lefkon.

There will also be screenings attached to the book signing of some Disney and Pixar films:

- Screening Schedule

John Canemaker’s

Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft

October 1–2, 2010

Friday, October 1

7:00 John Canemaker’s Two Guys Named Joe. Canemaker discusses the work of Joe Grant and Joe Ranft in a lecture extensively illustrated with film clips and still images. Program 75 min. Introduced by and followed by a book signing with Canemaker.

Saturday, October 2

2:00 Fun with Mr. Future. 1982. USA. Directed by Darrell Van Citters. Joe Ranft contributed gags to this zany short, which was cobbled together from animated bits of a shelved Epcot TV special and is hosted by a talking Animatronics head (with wires exposed) wearing a bowtie. Courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 8 min.

Luxo Jr. 1986. USA. Written and directed by John Lasseter. The first film to be produced by Pixar Animation Studios after its establishment as an independent studio, and the first CGI film to be nominated for an Academy Award. 2 min.

Tin Toy. 1988. USA. Written and directed by John Lasseter. This Academy Award–winning short anticipates Toy Story in its use of anthropomorphic toys as characters. 5 min.

Toy Story. 1995. USA. Directed by John Lasseter. Story by Lasseter, Pete Docter, Joe Ranft, Andrew Stanton. 80 min. Program 95 min.

5:00 Mickey’s Gala Premier. 1933. USA. Directed by Bert Gillette. Animation character designs by Joe Grant (uncredited). Grant’s first film at Disney, for which he designed all the celebrity caricatures. 7 min.

Who Killed Cock Robin? 1935. USA. Directed by David Hand (uncredited). Story and animation by Joe Grant, William Cottrell (uncredited), and others. Grant and Cottrell devised the satiric story, and Grant designed the characters, including Jenny Wren, a caricature of Mae West. 8 min.

Lorenzo. 2004. USA. Directed by Mike Gabriel. Screenplay by Gabriel, Joe Grant. An Academy Award–nominated short about a blue cat whose tail has a mind of its own. Grant created the concept, story, and character for this, his last film at Disney. Courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 5 min.

Dumbo. 1941. USA. Directed by Ben Sharpsteen. Screenplay by Joe Grant, Dick Huemer. Courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 64 min. Program 85 min.

- The school of Visual Arts is having an in-house exhibit of Art called:

- “Ink Plots: The Tradition of the Graphic Novel at SVA. It’s an exhibition of original drawings, books, prints and animation by over 100 artists.

Ink Plots traces the development of sequential art over four decades with selections from SVA faculty members and showcases

the work of SVA alumni who are pushing the boundaries of the graphic novel today.”

Ink Plots: The Tradition of the Graphic Novel at School of Visual Arts

is an exhibition of original drawings, books, prints and animations by over 100 artists. Ink Plots traces the development of sequential art over four decades with selections from SVA faculty members and showcases

the work of SVA alumni who are pushing the boundaries of the graphic novel today.

VISUAL ARTS GALLERY

601 West 26 Street, 15th floor, New York City

Gallery Hours: Monday – Saturday, 10 – 6pm

EXHIBITION:

October 8 – November 6, 2010

RECEPTION:

Thursday, October 14, 5:30 – 7pm

Free and open to the public.

Honoring past and present SVA illustration and cartooning faculty members including:

Sal Amendola_______Sue Coe

Harvey Kurtzman_______David Mazzucchelli

R.O. Blechman_______Will Eisner

Keith Mayerson_______Jerry Moriarty

Tom Gill ____Mark Newgarden

Edward Gorey_______Gary Panter

Burne Hogarth_______Jerry Robinson

Klaus Janson_______David Sandlin

Frances Jetter_______Walter Simonson

Ben Katchor_______Art Spiegelman

Peter Kuper_______

Benefit

Thursday, October 14, 2010, 7 – 10pm

MIDTOWN LOFT AND TERRACE

267 Fifth Avenue, 11th floor, New York City

Shuttle service from the reception to the cocktail party will be provided.

Individual tickets are priced at $250 with $100 tickets available to SVA alumni.

Proceeds from the benefit will be used to establish a scholarship fund for SVA illustration and cartooning students.

Tickets to the cocktail party may be purchased online at alumni.sva.edu/tickets or by calling 212.592.2302 or by

e-mailing serwin@sva.edu.

Other Ink Plots related Events

WILL EISNER,

MASTER TEACHER AT SVA Monday, October 18, 7pm

SVA Theatre, 333 West 23 Street

New York City

Free and open to the public.

INK PLOTS

PANEL DISCUSSION

Wednesday, October 20, 7pm

SVA Theatre, 333 West 23 Street

New York City

Free and open to the public.

DISTINGUISHED ALUMNUS

LECTURE WITH DASH SHAW

Thursday, November 4, 7pm

SVA Theatre, 333 West 23 Street

New York City

Free and open to the public.

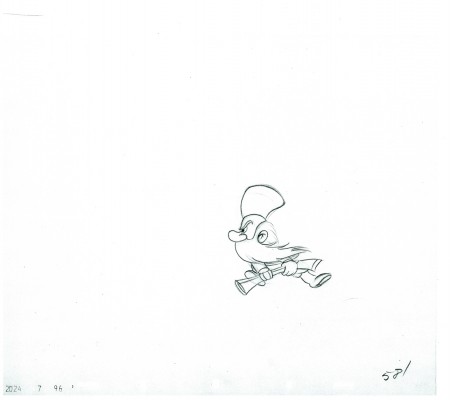

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 04 Aug 2010 06:21 am

P&W-Kimball Scene – 8

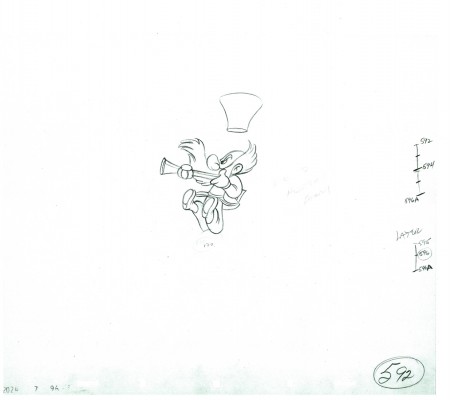

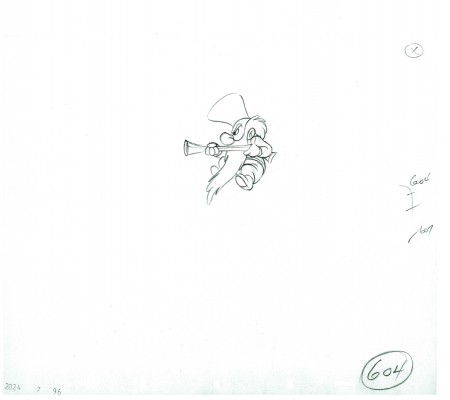

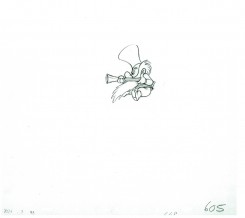

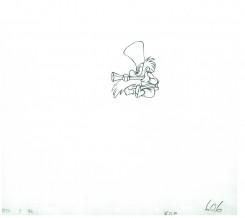

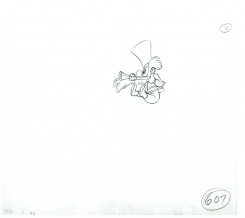

- Production #2024, MAKE MINE MUSIC, “Peter and the Wolf”. Sequence 7, Scene 96. Animator: Ward Kimball.

Completing the post of the little guy on the separate level, here are the final drawings of the scene. There are other levels of snow animation and footprint animation, but I won’t post those. This scene was large enough.

As usual, we start with the last drawing from last week’s post.

Enjoy.

581

581

The following QT movie represents all the drawings of the bottom level

as well as the drawings of the Little Guy, on another level,

who comes in and out where he should.

I exposed all drawings on ones.

Right side to watch single frame.

To see the past five parts of the scene go to:

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, and Part 7.

My thoughts on this scene – just my opinion

I’m pretty disappointed in what I’ve seen here. The work has the obvious flair and panache of a typical Ward Kimball scene. The movement is funny and creative. Kimball did his work. The assistants were out to lunch.

The drawing in the scene is not the top notch material I’d expect of a Disney team. Seeing it drawing by drawing I get to see what I don’t like from a lot of the work in this period. The drawing just changes and doesn’t live up to the originals. Just looking at the fingers you get to see them turn into, what we in NY call, “Banana fingers” – they flatten out. This is part and parcel of the work at Terrytoons or Paramount, but we’re talking Disney here. You wouldn’t catch that in Sleeping Beauty or Bambi or Dumbo or Snow White or 101 Dalmatians. But it’s there in these compilation features.

Now going through the many drawings I’ve posted by Bill Tytla, I notice a distinct tie to Terrytoons. In the dwarves and especially in Stromboli a soft roundness comes into his drawings (and the assistant keeps it) at times. It’s probably the influence of Connie Rasinski while Tytla was there. It isn’t a bad thing, it’s certainly part of the style Tytla brought to his work. He took something good from Terry (the bottom) and brought it to Disney (the top), and he made it work into something glorious. If anyone was an artist in animation, it was Bill Tytla. But that isn’t what I’m talking about with the work in this Kimball scene.

All right the schedule was probably ridiculously tight – it was – and the budget was probably underbudgeted – it was. But I remember Jack Schnerk (who assisted at Disney) telling me about the last six months of work on Bambi when work went into overdrive. Everyone was forced to work seven days a week and most slept on their desks to get it done. The work was so heavy he quit after the film was finished. But then that was pre-IATSE and the compilation features were not. That was also when Walt was intimately involved in the films and he was not so involved in the compilation films.

Something different: for some reason WordPress will not let me save the word “‘O’nion” (replace a “U” for the “O” and you’ll have the word I mean.) If I try to save a piece with that word in it, it erases the material. I’ve used IATSE in its place for this piece. This has gone on for the last year. Anyone with a suggestion?