Search ResultsFor "disney model sheets"

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 15 Dec 2009 08:47 am

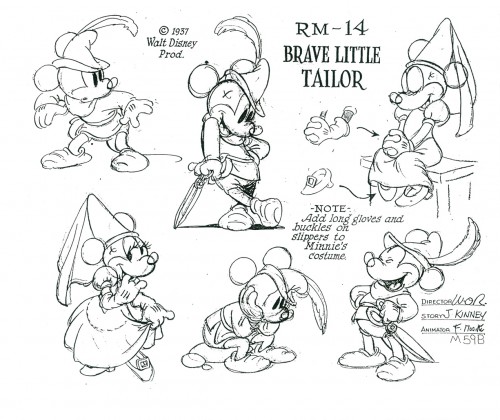

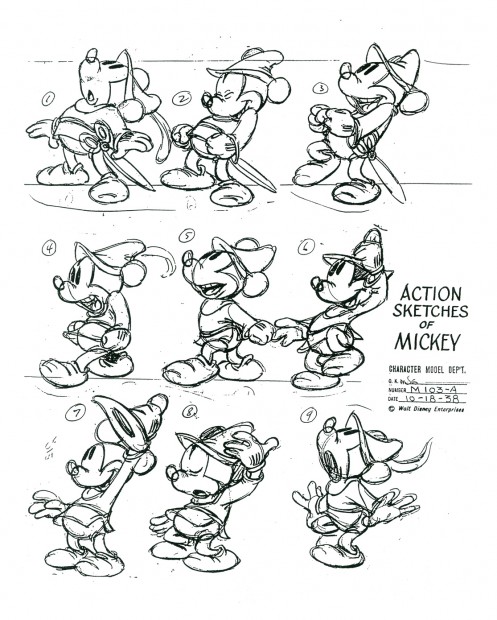

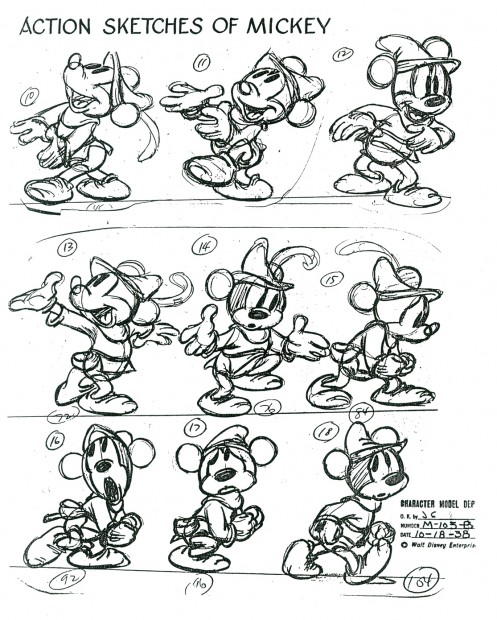

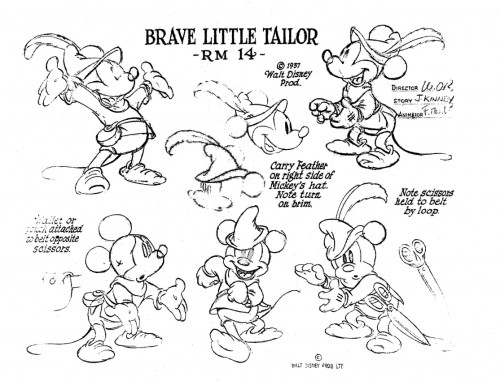

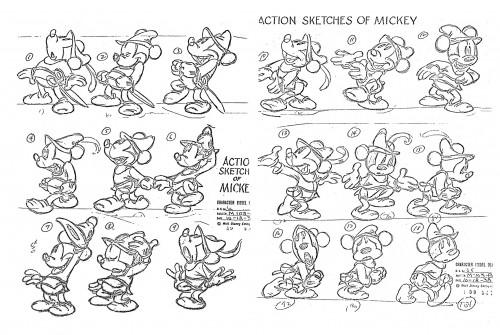

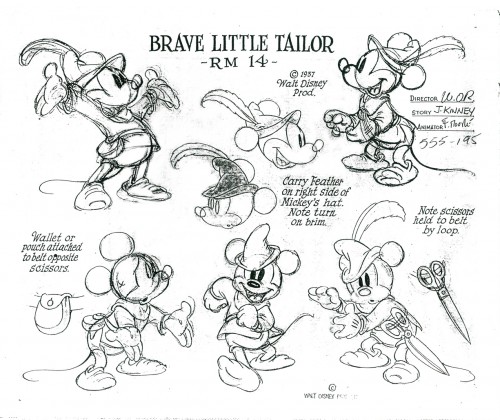

Mickey the Tailor

Bill Peckmann recently sent me another stash of model sheets, especially of Mickey, Donald and Goofy. Among them were four pages of Mickey from The Brave Little Tailor. This film, of course, is a gem, and I can’t help but admire the drawing on these model sheets.

Two of them are clippings from animation by Fred Moore. There are some clues as to the exposing of the scene, so I took the drawings apart and ran them through AfterEffects just for my own entertainment. Here are the results, below. First all four model sheets; then the QT movie I made of the actions.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Mickey the Tailor

Click left side of the black bar to play.Right side to watch single frame.

Articles on Animation 06 Nov 2009 08:41 am

Ed Benedict – Animafilm Intvw

- Amid Amidi in Animation Blast #8 printed a brilliant interview with Ed Benedict. There was another interview in the European magazine Animafilm 6, 1980. It was written by Dana B. Larrabee.

Ed Benedict on Animation

We have often dealt in our journal with the prospects of computer animation. We believe that also the views of an advocate of the traditional methods of animated film deserve popularization.

Ed Benedict first spoke to me on the telephone about an animated tv spot I had done for a local car dealer. When 1 learned of his extensive hack-ground in animation, I asked it” we might meet and talk further. Shortly thereafter we met twice at his home in Carmel, California.

Ed Benedict first spoke to me on the telephone about an animated tv spot I had done for a local car dealer. When 1 learned of his extensive hack-ground in animation, I asked it” we might meet and talk further. Shortly thereafter we met twice at his home in Carmel, California.

We talked mostly of the views Ed has developed during his forty-plus years in the animation business. From those interviews I have assembled the following for those interested in a personal ac-count of the craft and business of animated filmmaking as it has evolved in the United States.

It wasn’t a business. It was a group of guys that had to organize themselves for eight hours of the day basically.

In 1930 Ed went to work for the Walt Disney Studios as an apprentice inbetweener. The Mouse was an established cartoon character then, and Walt trying to launch a new kind of cartoon series that did not feature a regular character. These were the “Silly Symphonies”.

Ed recalled: – When I first worked at Disney’s (show you how thorough that guy was), we were required to make our own little animation tests. This is when we were just assistants. We’re not animators yet. I did a horrifying job when I think of it now, of a guy taking a horn and blowing it. That sounds pretty damn simple . . . and it could look like it too. And you could do it and it would look like, “Oh, brother! Is that keen!” A guy big, full of air: then blowing out, turns thin, you know. No animation. Just going from A to B. But we had to do it our own way. Start with nothing. No instructions. Just a blank piece of paper, and how many drawings we took to do it, that was our own thing.

We had to take all of our test papers in to the test-camera which was a little Tinker Toy baling wire rigged-up thing. This was at the first studio on Hyperion. He wasn’t making cameramen out of us. He was just rubbing our noses in the business.

So you got kind of an overview – I interjected.

So you got kind of an overview – I interjected.

Yes. An appreciation for every department. Then the cameraman would take it out and develop it – and not print it. We’d just look at the negative on the Moviola. We would get our strip of film and that was it. At the end of the day Walt would come around and look at it with us and just go over it.

There was one of the early “Silly Symphonies ” called “The China Plate” (1931) when I was assistant to Rudy Zamora. One of the scenes was trucking in on one of these plates with Chinese scenes painted on it. Rudy had this scene and he was quite delighted to have thought to do this himself; I remember him leaning over to me, flipping the animated drawings saying: “Hey, how do you like this?”

You know these little Chinese girls with the little Chinese bobs? Straight bobs. Whether they ever had them or not, I don’t know. That’s the way we thought of them at the time. This little girl was to turn from left to right – but when she turned, the hair trailed across her face. That had never been done before. That’s a first beginning to loosen up things. Not only animating the figure from here to herc~but there’s little things on them too, where a thing will trail an action and then come back again and then settle down. It was just sort of lifelike.

He also worked under Wilfred Jackson {who had previously been an assistant to Ub Iwerks) doing breakdown, clean-up and inbetweening.

I’d been there a couple of months and we were working on this picture that had an Indian character ot a fox fighting with another character. I noticed that in this particular scene the fox’ tail was missing. When I remarked on it to Jackson, he said there was so much action that no one would miss it. I guess you could say that was my first experience with the “facts of life”.

He chuckled and continued: – Jackson was to later become a first class triple-plus director . . . and he was the last guy in the place that looked like it. A wonderful guy . . . straight . . . and he didn’t appear to have a sense of humor. He just didn’t look like he belonged in that business. But I guess he was the first genius of the directing end who knew to get the “Disney” out of the Disney Product.

In 1933 Benedict went to work for Walter Lantz at Universal as an assistant animator. Then he worked for Charles Mintz at Columbia for a year-and-one-half before returning to Universal where he became a full fledged animator. It look an average of four years to make animator, Ed recalls.

Then on the side with a co-worker at Lantz’, he set up an independent company. They first tried to interest Richfield Oil in the idea of animated billboards – a project Ed describes as “successfully unsuccessful”. Then he hit on the notion of selling commercial ideas to independent theatres. But without a distribution set-up, the idea “took a long time to develop into a state of nothing”.

From 1938 Ed worked with Paul J. Fennel at Cartoon Films, Limited making commercials for Borden’s, Shell Oil, Rinso, etc. He returned to the Disney organization in 1942.

Did you work on “Willie, the Operatic Whale”? I asked.

Yeah. I worked with Ken O’Connor on that. An excellent artist.

Ed went on to explain about the drawing materials used by the animators.

The paper that everybody used to use was called Management Bond.

What kind of ink did they use on the cells? I asked.

I can tell you back then it was India. And there were Gillot pens and there were other kinds of pens for certain widths. And then they started getting these spread lines and working with brush. The girls had to be pretty sharp with a brush. You couldn’t just take any girl, like with a pen. A girl had to be trained with a pen for tracing before she’d get into brush. Ed was kept busy at Disney’s doing “war stuff”. He worked on an aerology series for the Navy and Victory Through Air Power as well as educational films. This period of employment with the Disney organization lasted three years. After the war, he took a leave of absence to help Paul Fennel found his own cartoon studio.

About this time United Productions of America, better known as U.P.A. was getting under way.

Now U.P.A. was my idol. U.P.A. was the greatest – Ed enthused. Steve Bosustow was living down in Santa Monica on the beach and one time I visited with him. And in one of the rooms on the wall was a bunch of story sketches that he wanted to show me, things they were working on. They were a little weird-ish compared with the typical bulb-headed looking things. They were attractive and intruiguing. And that was the beginning of U.P.A.

It was later taken over by a different outfit – made a garbage can out of it. Like the Dusenberg. gone. Period. End. Fin.

Later Ed called Tex Avery at M.G.M. (whom he knew from his days at Universal) and asked him if he needed a layout man. In animation “layout” refers to the design and relation of the cartoon characters to the backgrounds and to the total visual concept of the film as a whole.

Ed explained: – You see when I left Universal I was an animator. But with Paul I was laying out and doing the models – everything. So I got away from animation – animation bored me. I don’t know. I wasn’t a good animator. But my inclination ran towards more drawing. So laying out and models got to be my thing from then on.

By models, do you mean model sheets? For the characters?

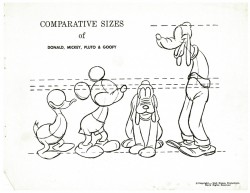

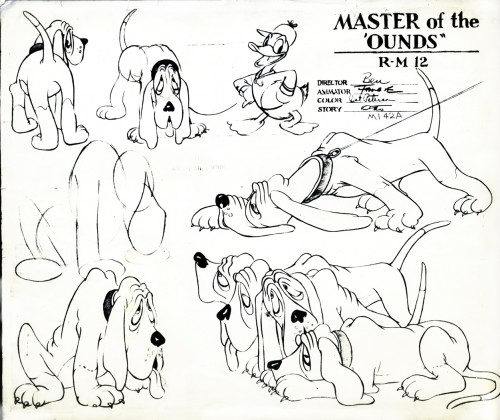

Not model sheets – models. Just a drawing of the one character . . . and overall three-quarter thing showing what it’s all about. Model sheets are based on models.

The model sheets are referred to by the animators as they work on their scenes. They show the characters in multiple views, different poses, expressions, etc., and their proportion to other characters they may be working with. By doing models Ed was designing cartoon characters.

At M.G.M. Tex Avery gave me a model sheet of Droopy to see what I would do to modernize it. He liked what I did and said; – Okay, come to work.

Later M.G.M. started cutting down. And TV started to cut in. So Tex’ unit was cut out. But Bill and Joe (Hanna-Barbera) wanted me to stay there and work for them. I didn’t work on “Tom and Jerry” – but other special pictures they were doing. Then the thing got cut way down. I left the place and was home doing comic books for awhile. And then I got a eall from Quimby (Fred Quimby was in charge of the cartoon units at M.G.M) to come in and talk to him about doing the set-up for this Gene Kelly thing. This was a whole picture -not just a sequence. It could have been really good-looking but they were all too sissy about it.

In the meantime Tex established his own commercial unit, Tex Avery Cartoons, and is sending over model jobs for me to do via one of the animators that worked at M.G.M. who was doing outside work for Tex. Hell, I was making more working a half-hour on a model (for Tex) on M.G.M.’s time than I made a whole day sitting there for M.G.M.!

Things were getting pretty hot over here, beginning to fold up. And Joe and Bill are working on things of their own. I did the Ruff ‘n’ Reddy models for’em. Anyway, we’re doing commercials over at M.G.M. for a while. For Schlitz, S-H stamps, and then the thing folded. Meanwhile I’ve been doing models and commercial layout for Tex. Hell, I’m making a minimum of twice what I was getting at M.G.M. I was doing all the H-B models “Huckleberry Hound”, “Quick Draw Me Graw”, “Flintstones”, etc. as well as the layouts. Now when they get loaded down at H-B, I get a call.

I asked Ed about working with the numbering system I’d heard was used at Hanna-Barbera. He called it a “file and number system”.

It was driving me crazy – he sighed. You would spend more time getting up from the board here and going over checking the files and numbers to see where you’re going . . . or looking up the right background. It would’ve been less work if I’d done the whole thing myself.

What about the u-nions? I asked. What’s the difference between the two, if any?

I can’t say what he is now – he emphasized. I can say of the middle era (The ‘forties and ‘fifties). The screen Cartoonists ‘Guild was considered a “Liberal” u-nion. The Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists was part of the I.A.T.S.E. It was considered the more moderate of the two.

If you’re looking for work in Hollywood, do you have to belong to the u-nion to get in down there?

Yeah. Furthermore, they’re not that long on work. So all the u-nion guys would have to come first.

I moved up here in ‘sixty-one. If the work followed me -fine. If it didn’t, the Hell with it! I’d had it. And I’d never liked it since I’d been in the business anyway. There were very few “talented” guys in the business. But the ones that had it – like Art Babbitt, Tom Oreb, John Hubley, Bob Cannon and Norm Ferguson – they were real geniuses! But many of the guys couldn’t draw their own breath. In the earlier days, the business was made up of cartoonists more than artists. Had there been more artists, there might have been a different picture.

Where did you think the future of animation lies?

I think it’s walking towards its grave. I can’t tell you how far it is between here and the grave. It’s like centuries ago when guys were carving with chisels, these ultra-fine hunks of lettering and sculpting in marble. The exactness. The fantastic things they were doing then. A guy could stand off and say: “Gee, that’s what I’m going to be when I grow up.” And you can go and keep saying it ’cause it was so beautiful, it was so superb-what’s better? But is it? There ain’t none of it. None. It’s just an old dead art.

Is that analogy valid for animation?

Sure it is.’

Why? Look at some of these television commercials…

That’s not animation. That’s using the animation medium … To me, most of it has no advertising value whatsoever… It’s just a lot of talk that somebody is trying to sell somebody and they’re not. The ad agencies are all wrapped up in their own immediately constructed little world. And they turn to each other and all of ‘em think: “This is ours”. Completely losing the total picture of whether it’s ours or yours or the next-door-neighbors’ . . . What’s it doing? What’s it supposed to do?

You don’t see any future in the business?

No.

Do you think it’s stupid to try getting into it?

Well, I can afford to be wrong. But for the most part . . . I would say “yes”. Stupid from the standpoint if you think you ‘re ever going to make something out of those things. But not stupid from the standpoint if you’re fascinated with it. If you’re intrigued to the point that nothing else will do, no, you’re not stupid. You’re smart. Go through and milk it . . . Being in the business was beautiful. Being in the business was keener than Hell. Informal! Friends of mine that had to work in offices – oh, they envied the Hell out of me. And I didn’t blame them!

With regard to the dollars and cents end of animated film making, Ed felt that the producer “might make a couple of bucks.” He cited ever rising labor and material costs as the main reason the profit potential in animation is lessened all the time.

Together we examined some “how to” books on animation by Eli Levitan and Roger Manvell. Later, Ed had this to say about them:

- Much of this stuff in the books was too much analysis. That never was done at all. That attitude just wasn ‘t there. It was more a natural reaction to things that they were seeing, or doing, or thinking.Finally we discussed “contemporary animation”. Ed took a pretty dim view of it all.

I was looking at these things on channel nine. And every one of ‘em are done in Yugoslavia or Arabia or some other place where the guys don’t make ten cents an hour. A gay is sitting down at a drawing board and doing anything that comes through his mind…I don’t even put it in the category of drawing. Animation? No such thing.

Have you seen any computer animation? I asked.

I have no use for it – he answered quickly. I have nothing but utter, unadulterated contempt for it.

Are you sure you’re not a little afraid of it?

Not in the least. It will never in your time touch animation. They are still a mathematically run machine. It hasn’t an iota of looseness. They’re finding out that computers have their limitations . . . It always has the same flavor, same attitude. It’s always there as a graph.

One can take issue with some of Ed’s opinions about animation as apart form and as a business. But what makes his remarks so compelling is his first-hand knowledge of the craft itself and of the many personalities who made the business of animation a “business”. His sentiments concerning the current “state of the art” are disconcerting to the animation enthusiast. But they are the outcome of his having been caught up in the rise and fall of the theatrical cartoon studio operations as well as the growth of a never, and to him, less satisfying sort of production geared to television.

I also suspect that this attitude stems from his own genuine concern for the craft – his frustration ai what animation has come down to as opposed to this notions of what it should be.

To some, Ed’s opinions may seem overly pessimistic. But before Ed would consent to this interview in preparation for this article, he forewarned me that he would not “romanticize the cartoon business”. He explained that this was his pet peeve with most of the articles and books that dealt with the history of his craft. And Ed Benedict was not about to further that sort of misrepresentation.

photos:

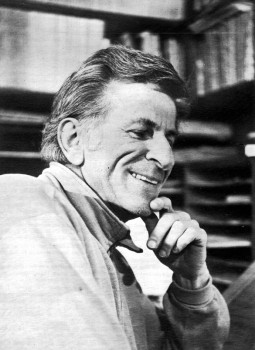

1. Ed Benedict

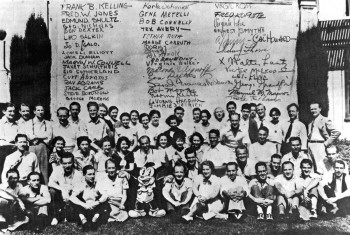

2. The Oswald the Rabbit team at Lantz

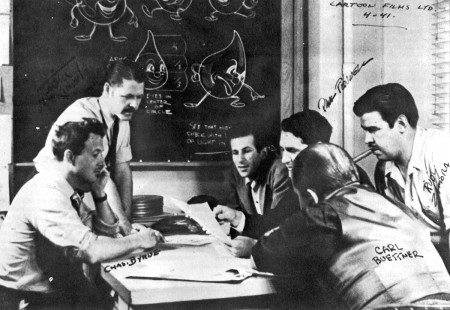

3. Ed Benedict among his collaborators

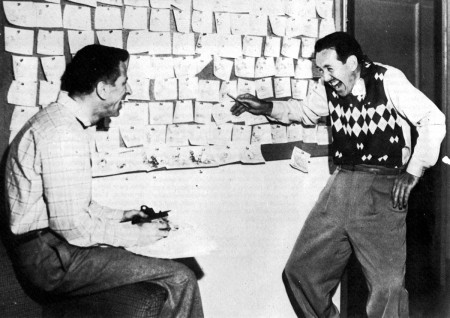

4. Ed Benedict and Mike Lah

A couple of comments.

- Sorry, I had to write the word “u-nion” that way because WordPress (on several different computers wouldn’t allow me to save that word. (Secret conspiracy?)

It’s unfortunate that Ed wasn’t asked more about his brilliant work at Hanna-Barbera. That’s where he truly came into his own and had such an enormous effect on the world of animation.

Animation &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models &Story & Storyboards 28 Sep 2009 07:36 am

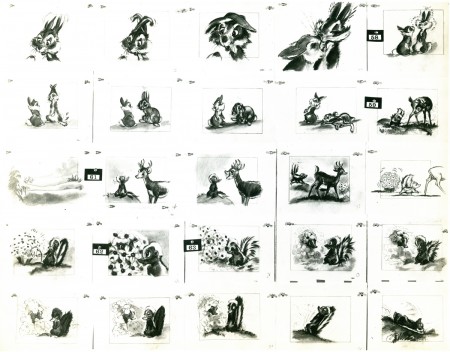

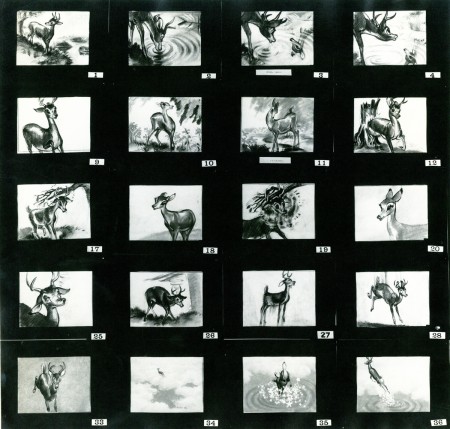

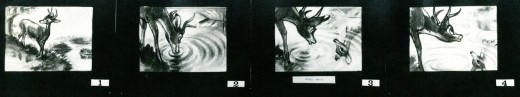

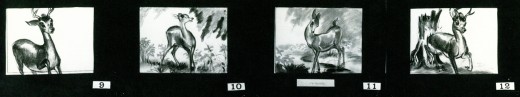

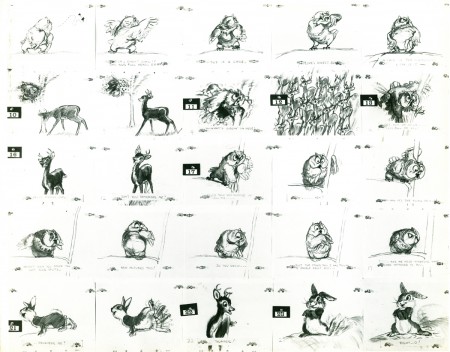

Bambi Board 2

- The cache of stats that Bill Peckmann recently sent me on loan includes several photo pages of storyboard from the Bambi Twitterpated sequence. I’m not much of a fan of this sequence, but looking at these beautiful storyboard drawings makes me realize how charming it is in its original state. The cute/cartoony movements came from the animators and directors. Perhaps the film needed this funny, broad approach, but I have a feeling there are other ways it could have been tackled that might have let it feel more connected to the whole.

As with past board postings, I’ve cut them up into rows so that I can post them at a higher res for better viewing. First here are the three pages as they stand:

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

Now here they are again broken into individual rows:

1a

1a

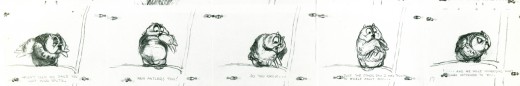

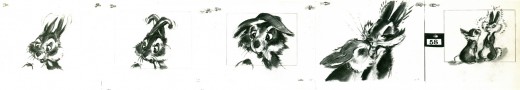

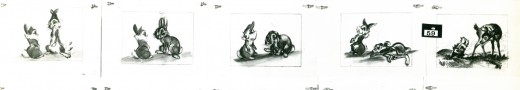

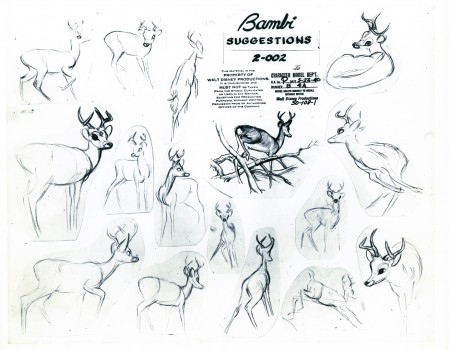

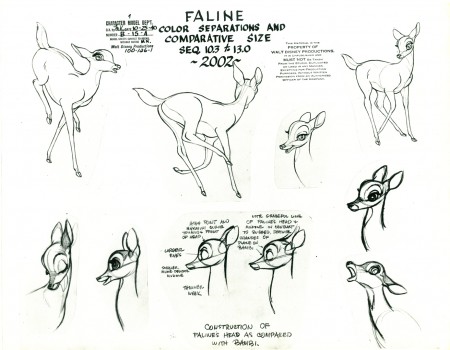

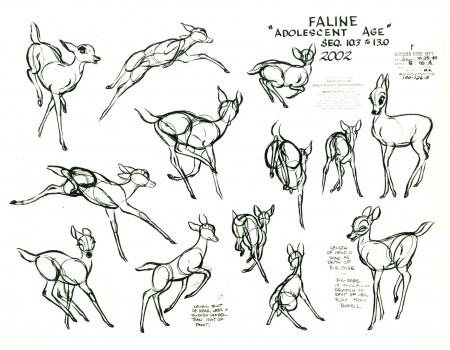

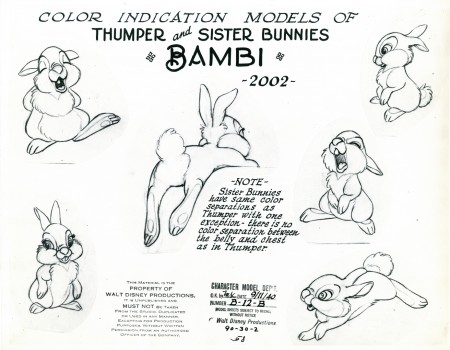

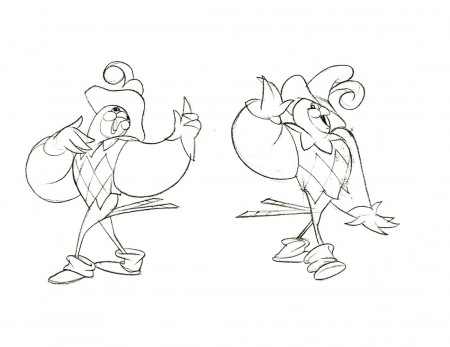

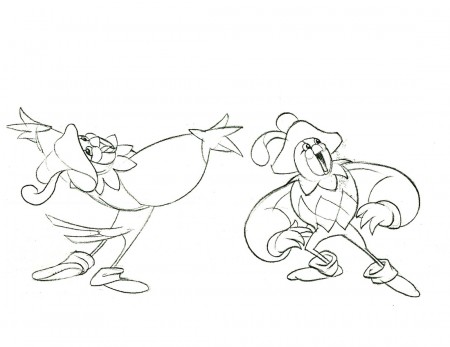

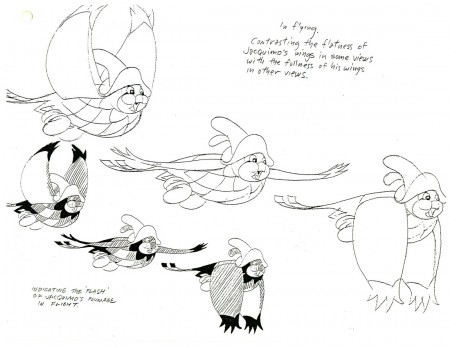

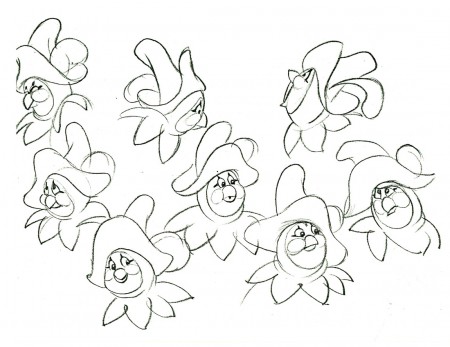

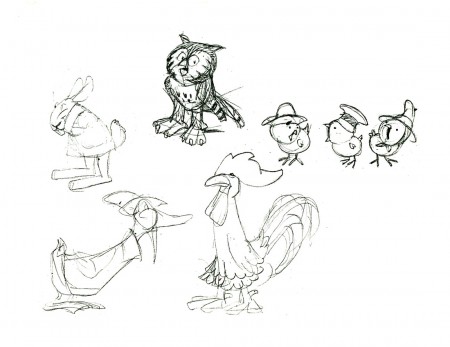

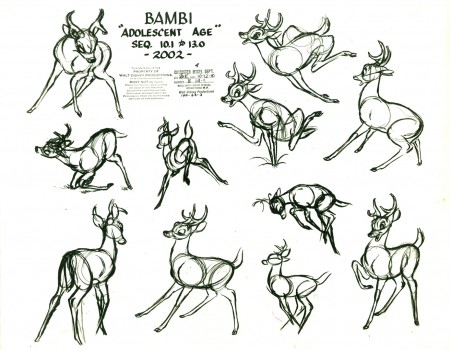

Here are some model sheets which relate to this sequence:

1

1

Once again, many thanks to Bill Peckmann for the loan of this marvelous material. It’s truly appreciated, and it’s fun to share.

It’s amazing to think how Walt Disney pushed all this great art forward. This film actually moved the “Art” side of animation forward with the majestic backgrounds, realistically designed animation and bold storytelling approach. There’s no possibility that something as rich as this film could be done today.

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 14 Sep 2009 07:27 am

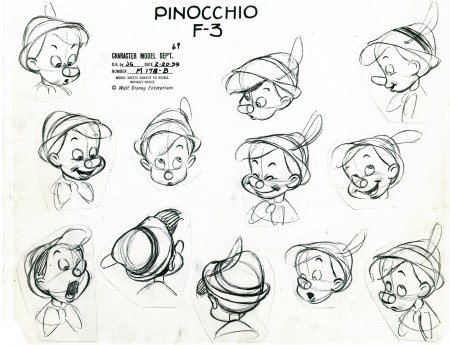

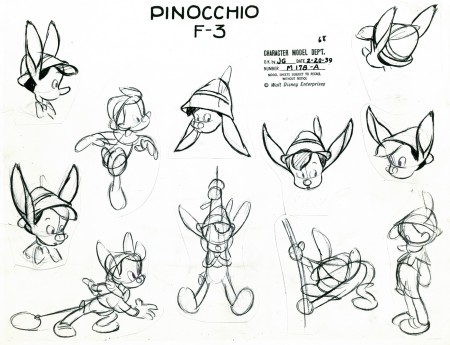

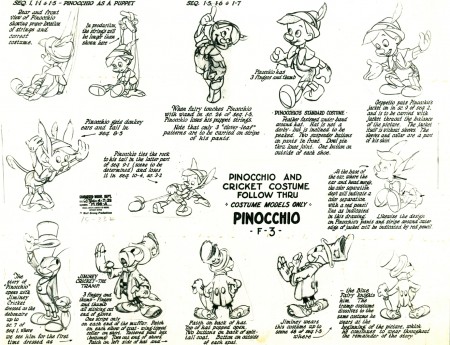

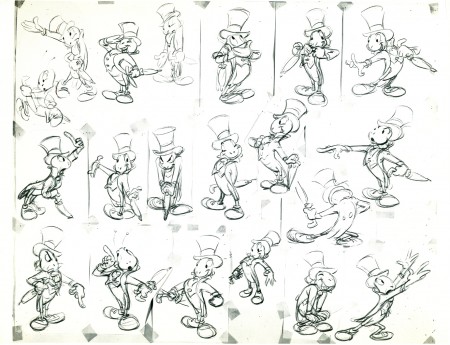

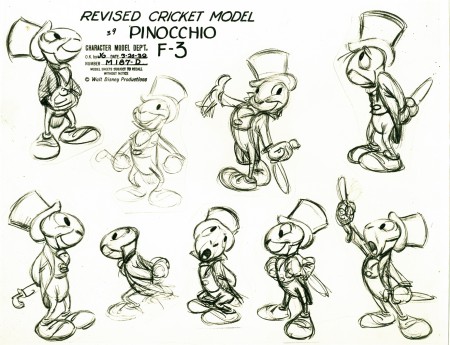

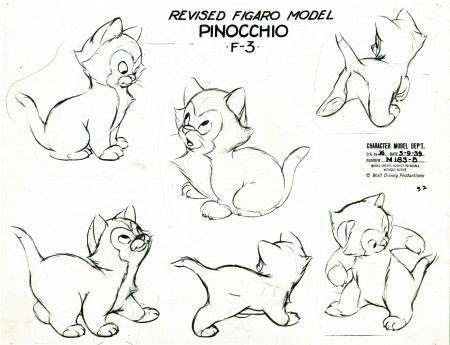

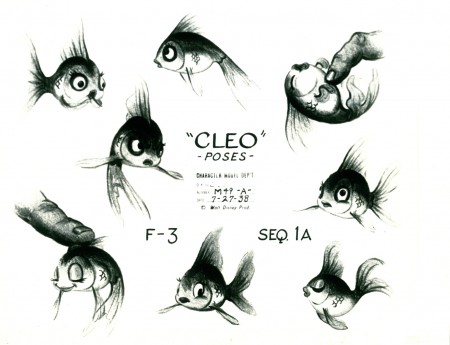

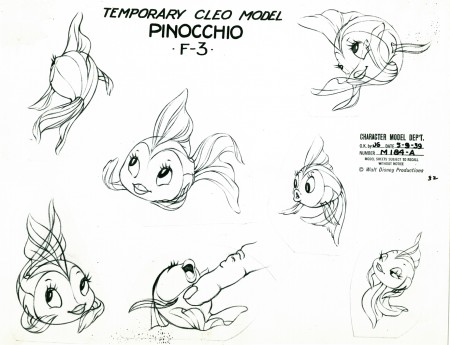

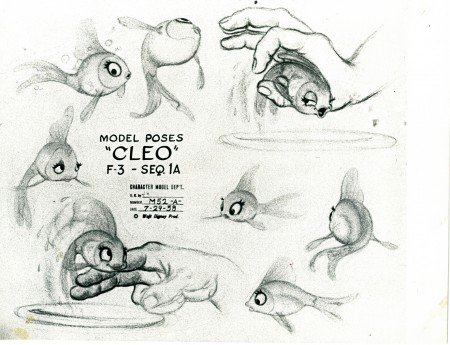

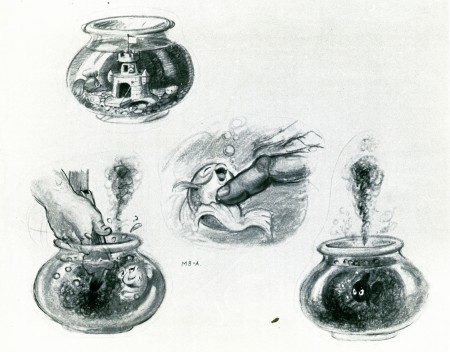

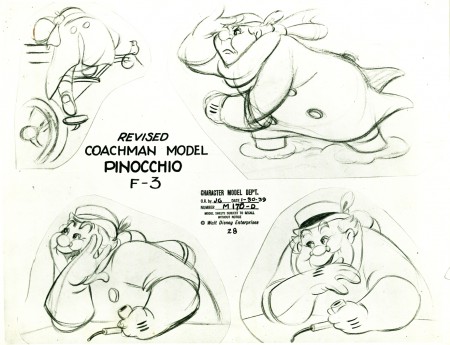

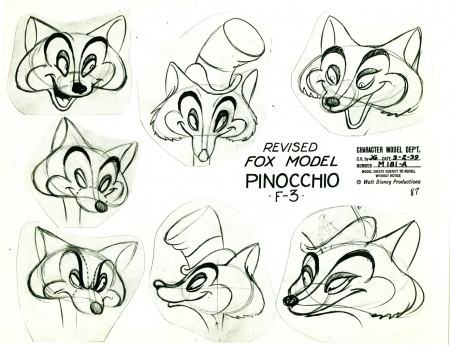

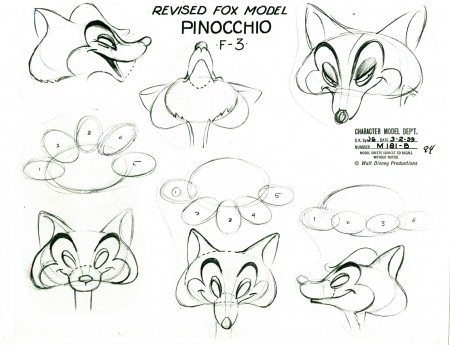

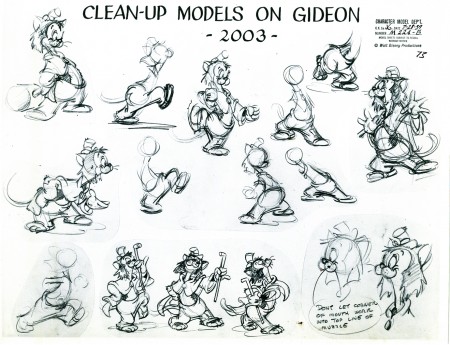

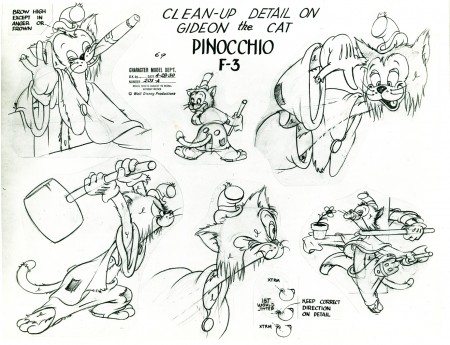

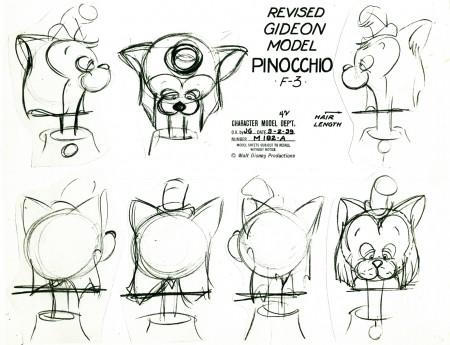

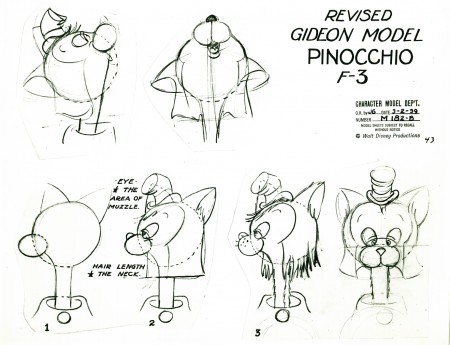

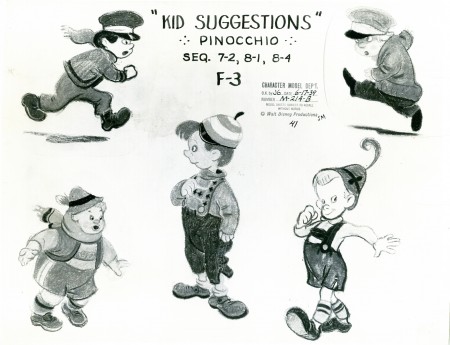

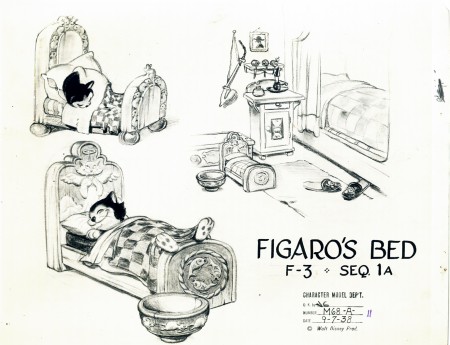

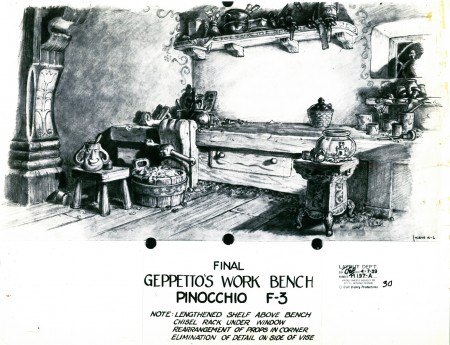

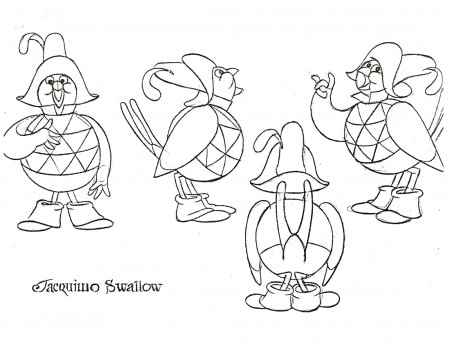

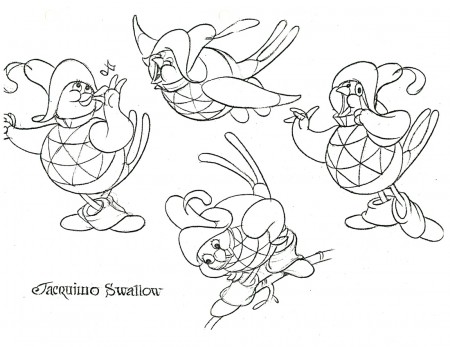

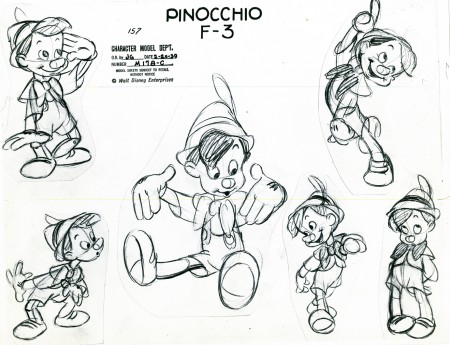

Pinocchio Model Monday

- As I did with the past few Mondays, I’m posting some Disney model sheets on loan to me from the generous Bill Peckmann. Here we have Pinocchio. I’ve seen about half of these models before – usually in much worse states – though some of them are very new to me. (Check out #5, #11 & #20.) All are photostats and in fine shape. This film is an inspiration to any animator, so they’re fun to post.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

What! No Gepetto?

I do have this badly damaged 16fld cel. After all, he has to be represented. And when would I get a chance to show it off?

Articles on Animation &Disney 05 Sep 2009 07:41 am

Snow White at 50

- Last week I posted an article about women in animation which originally appeared in Sightlines Summer/Fall 1987 issue. I’d also mentioned that the very same issue had an article by John Canemaker about Snow White’s 50th Anniversary. Naturally, I have to post that article as well. It ties in with the recent issue of D23 wherein John has an article about Snow White celebrating a new remastering of the film and the ways it continues to inspire new animation artists. This is its 72nd anniversary.

Here’s the article:

This year, Walt Disney’s first animated feature, SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS, celebrates its golden anniversary with its re-release in some 2,000 theatres in North America and in venues in 60 countries overseas. The blitz of media events and publicity has encompassed proclamations, parades, and public appearances; soft-drink, clothing, and book tie-ins; a TV special; and, according to Jon Lang, Disney’s director of film licensing, “More merchandising for this movie than any other, including STAR WARS.” Even a Snow White rose has been created, with 100 bushes shipped to mayors in 40 major cities.

This year, Walt Disney’s first animated feature, SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS, celebrates its golden anniversary with its re-release in some 2,000 theatres in North America and in venues in 60 countries overseas. The blitz of media events and publicity has encompassed proclamations, parades, and public appearances; soft-drink, clothing, and book tie-ins; a TV special; and, according to Jon Lang, Disney’s director of film licensing, “More merchandising for this movie than any other, including STAR WARS.” Even a Snow White rose has been created, with 100 bushes shipped to mayors in 40 major cities.

To date, the half-century-old SNOW WHITE has worldwide grosses totalling more than $330 million, making it one of the most popular motion pictures of all time and the movie that saved the Disney studio from financial disaster. “You should have heard the howls of warning when we started making a full-length cartoon,” recalled Walt Disney years later. Hollywood pundits called it “Disney’s Folly,” and predicted no one would sit through a seven-reel cartoon.

One of Disney’s reasons for producing SNOW WHITE as a full-length, animated cartoon was financial: The introduction of double-features during the 1930′s bumped Disney’s one-reelers—his cartoon “fillers”—off the screen. The other reason was an artistic one: A bold visionary and innovator, Walt Disney wanted to make full use of his staff’s extraordinary skills, which were developed during the making of his short films. Starting with Mickey Mouse’s debut in 1928, the Disney studio artists made remarkable and steady progress in expanding the stylistic and narrative parameters of the animated cartoon.

Disney’s introduction of certain technological elements-sound and color—forced animation to change. Soundtracks dimensionalized a character’s personality and toned down the over-exaggerated pantomime favored by the silent cartoons. In 1932′s FLOWERS AND TREES, one of Disney’s experimental Silly Symphonies (a series of shorts begun in 1929), Disney utilized a three-toned Technicolor process that allowed for a full range of hues. Old graphic formulas for characters and forces of nature were gradually redesigned to convey the illusion of reality and sincerity that Walt saw in his mind’s eye. The plots of the shorts came to be based on the personalities of the characters, rather than on mere action or gags. Thus, the emotional possibilities for animation were extended as never before.

Unprecedented Problems

The problems encountered in the making of SNOW WHITE were unprecedented. More than 750 artists worked on the film for three years, creating at least two million drawings (of which 250,000 made it into the film).

One of the most formidable problems was the animation of the human figures. The Princess, the Queen, the Prince, and the Huntsman had to be convincing for the melodrama to work. Indeed, the audience had to truly believe that two cartoon characters were going to murder another cartoon character. Previous unsuccessful attempts to portray human motion included the 1934 Silly Symphony, THE GODDESS OF SPRING. To overcome the drawing problems and stiff animation of that experiment, Disney established art classes on the studio lot. All staff artists were obliged to attend in order to study films frame-by-frame and to draw from a nude model. In addition, live models were filmed for the animators to study; interestingly, the model for Snow White was a young dancer who later became famous as Marge Champion.

The animation of the human characters works, for the most part, but is spotty. Snow White has a unique, sweet charm, but the poor Prince is never more than a cardboard symbol of a romantic hero. In contrast, the seven dwarfs are superbly realized. “These inspired gnomes,” wrote New York Times caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, “with their geometrical noses, flexible cheeks, linear mouths and eyes, highly stylized beards and costumes . . . lend themselves to articulation because of the tremendous magic of well-directed lines. But the characters Snow White, Prince Charming, and the Queen are badly drawn attempts at realism. … To imitate an animated photograph, except as satire, is in poor taste.”

For SNOW WHITE’S feature-length format, the violent, fast action and bright colors used in Disney’s earlier short films had to be softened and paced to sustain audience interest. Muted earth tones of green and brown predominate, and the extensive use of shadows enhances cool forest scenes, as well as bright meadows and moonlit castles. Snow White’s nightmarish escape through the forest is a scene full of rapid cuts and violent movement. It is followed by the sequence in which the forest animals discover Snow White, which is gentler and slower-paced than the one that precedes it.

The score, eight songs by Frank Churchill and Larry Morey (including “Whistle While You Work,” “Someday My Prince Will Come,” and “Heigh-Ho”), advances the plot and adds to our knowledge of the characters and their motivations, desires, and inner thoughts. The integration of songs with the plot precedes Broadway’s Oklahoma by six years.

Disney’s greatest personal input was in the development of the script and the personalities of the characters. The final scenario is admirably lean, clocking in at 83-action-packed minutes. While the story is succinctly told, it is also filled with details, the result of three years of intensive story conferences and ruthless storyboard critiques by Walt and his creative staff. Six months of work on the film was scrapped by Disney, and he ordered entire scenes redrawn. Three sequences in story-board or rough animation were cut from the film, not because they were bad, but because they impeded the flow of the story. At a recent press conference at the new Disney animation studio in Glendale, California, drawings and test footage from those “lost” sequences were shown. It was apparent that those sequences—which feature the dwarfs’ bed-building routine, soup-eating song, and a dream ballet with Snow White and the Prince—would have been as charming and entertaining as anything that remains in the film.

Disney’s perfectionism drove up the cost of the movie, produced during the Depression years of 1934-37, to astronomical heights, from an initial $150,000 to $1.5 million. “As the budget climbed higher and higher,” said Walt, “I began to have some doubts, too, wondering if we could ever get our investment back.” There was a cliff-hanging deal with a bank to borrow more money; but as the world knows, SNOW WHITE finally proved a great success. The film made its world premiere on December 21, 1937, and reviews were glowing. SNOW WHITE initially earned $8.5 million at the box-office, an enormous sum for the time, especially since children’s movie tickets cost 10 cents.

Feminist Reassessment

Although SNOW WHITE is undeniably a masterpiece of American cinema and a classic of character animation technique, the film has recently become the focus of feminist reassessment and anger. Feminists argue that Snow White is a symbol of female passivity, as she waits to be rescued by an active male, who will give her life purpose and meaning. Film historian Sally Fiske suggests that in order to “comprehend the statement SNOW WHITE makes, imagine reversing it. Try to imagine that the dwarfs were seven little women and the title character was a young prince. The story becomes utterly inconceivable—which is a very telling comment about how we perceive women.”

Charles Solomon, writing in The Los Angeles Times about this subject, interviewed Karen Rowe, an associate professor of English at UCLA specializing in fairy tales and folklore. “While children need a sense that a young figure can confront problems and surmount them, heroes tend to overcome problems in more active ways,” claims Rowe. “What I think is problematic for the 20th century reader of popular tales-including the Disney versions— is that no provision is made for activity on the part of the heroine. It’s all rescue, all passivity. What that communicates to a female child is that it’s never by your own will or action that you overcome a problem. It’s through intervention on your behalf by some other figure. That undercuts any sense of growth and leads to a cultural emphasis on female dependency, which I think is very destructive.”

When SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS was made in the 1930′s, issues concerning women’s rights, feminism, and role models were not part of the social consciousness of the time. Our approach to viewing SNOW WHITE today should be the same as the one we bring to viewing other film classics, such as THE BIRTH OF A NATION, whose ideology is out of step with current important social issues. Parents should discuss such anachronistic screen images with their children, placing the characters within the context of the period in which they were created and supplementing them with alternative stories and female characters who are, as Professor Rowe says, “more affirmative of a young girl’s ability to act.”

John Canemaker, a contributing editor to Sightlines, ;s the author of Winsor McCay—His Life and Art, recently published by Abbeville Press.

If you want to see more pictures from Snow White, I posted a bunch of model sheets last Monday. Go here.

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Models &Rowland B. Wilson 03 Sep 2009 07:20 am

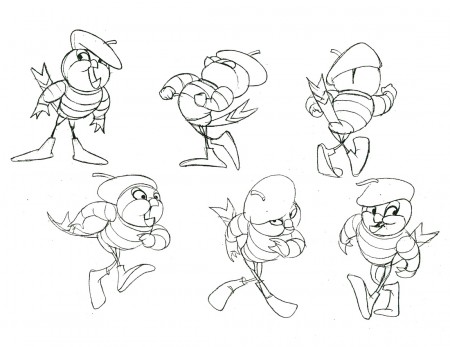

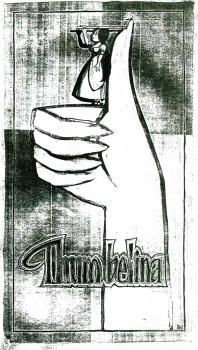

Rowland Wilson models

- In the past couple of weeks, we’ve seen a large group of Disney model sheets from some of the early shorts and features. I thought it’d be a good time to look at something more recent. Thanks to Bill Peckmann‘s extraordinary collection of design material, I have access to quite a few model sheets by Rowland B. Wilson.

- In the past couple of weeks, we’ve seen a large group of Disney model sheets from some of the early shorts and features. I thought it’d be a good time to look at something more recent. Thanks to Bill Peckmann‘s extraordinary collection of design material, I have access to quite a few model sheets by Rowland B. Wilson.

His models for Don Bluth‘s feature, Thumbelina, fill a binder. I’m gong to have to break it up into two posts.

In this first one I’ll reproduce the article Rowland had written for the in-house organ “Studio News.” This follows with models for some of the lead character models.

These models were done in pencil and ink, sometimes in color. Unfortunately, all of these are 8½ x 11 xerox copies. Blacks wash out and washes blacken. Regardless, they all come across fine enough to get the idea.

Any feature takes a lot of work. You can understand that just in the large number of model sheets that grace the production. When you have a talented artist such as Rowland Wilson doing that modelling for you, your art is off to a good start.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

1

1

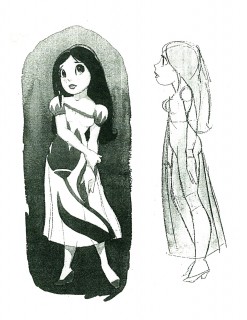

Here we have the model that Rowland drew for Thumbelina.

This is definitely not the rotoscoped princess that we saw in the film.

2

2  3

3

Here we have a lot of different costumes Thumbelina

will wear as she travels on her expeditions.

4

4  5

5

An original idea – a character who wears

more than one costume in a film!

Plenty of other models to follow tomorrow. Again, thanks to Bill Peckmann for the loan. It’s always great to showcase Rowland Wilson’s work.

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 21 Aug 2009 07:53 am

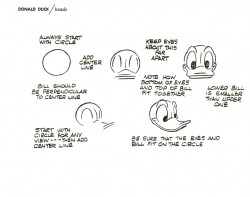

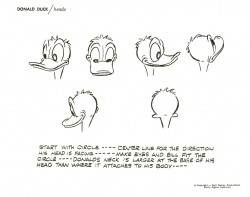

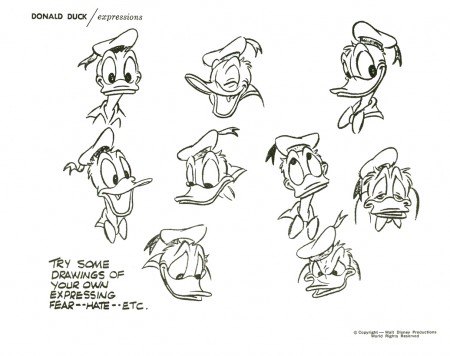

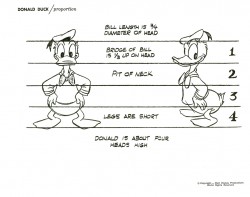

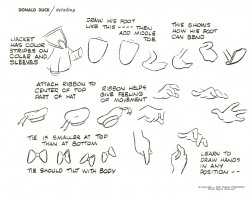

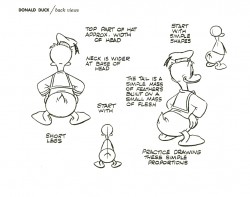

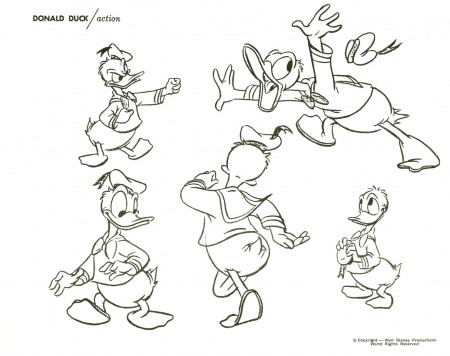

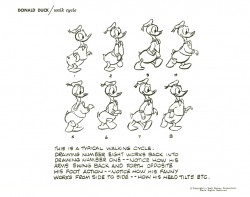

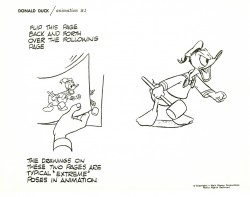

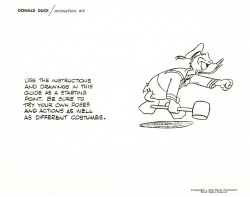

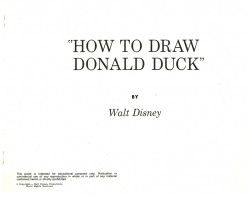

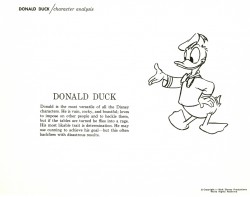

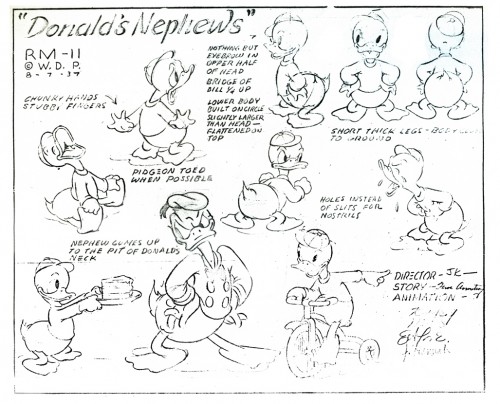

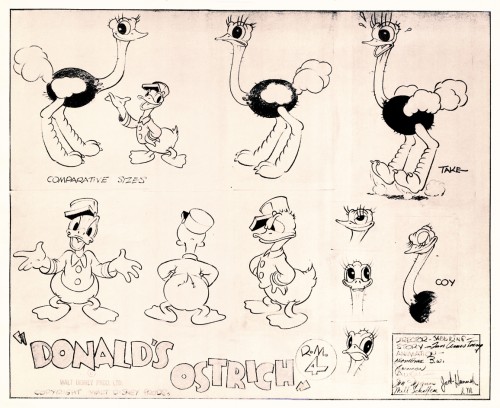

How To Draw Donald

- I continue with the Art Corner books from Disneyland with the How To Draw Donald classic. I’d received a full set of these books (How to draw Mickey, Donald, Goofy, Pluto and Chip & Dale) when I bought an Animation Kit from them. I’ve started posting these booklets after posting the lecture series that was given to the staff in the 1930′s.

Go here to see the lecture series posts:

Mickey / Donald / Goofy / Pluto

Here to see How To Draw Mickey.

Here to see How To Draw Pluto.

Here to see How To Draw Goofy (Jenny Lerew‘s Blackwing Diaries.)

Here’s the booklet:

1

1 2

2(Click any image to enlarge.)

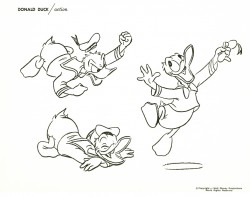

I don’t have a lot of Donald model sheets to add to this, but these three are interesting.

This last model comes courtesy of Bill Peckmann‘s collection. Many thanks.

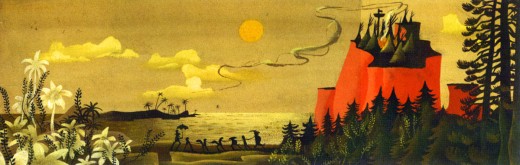

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Illustration &Mary Blair 19 Aug 2009 07:33 am

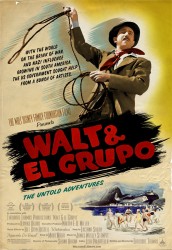

El Groupo & Mary Blair’s Peter Pan

- Yesterday I saw a preview screening of Walt and El Groupo. This is a documentary exploration of the Disney trip to South America to bring back material for Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros. If you have any interest in Walt Disney or the history of his studio or Mary Blair, you’ll have to see this film. It features interviews with a number of the children of those who went to South America with Disney. Interviews with those who hosted Disney talk about the visit.

- Yesterday I saw a preview screening of Walt and El Groupo. This is a documentary exploration of the Disney trip to South America to bring back material for Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros. If you have any interest in Walt Disney or the history of his studio or Mary Blair, you’ll have to see this film. It features interviews with a number of the children of those who went to South America with Disney. Interviews with those who hosted Disney talk about the visit.

The film is shot in a beautifully lush color that is almost reminiscent of IB Technicolor. One would expect the home movies to be grainy and unattractive, but instead they’re gorgeous.

The film is worth the visit. It’ll open in NY & LA on Sept. 11th. I’ll write more about it as the event gets closer.

There’s also upcoming a screening for MOCCA, the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art featuring a Q&A with writer/director Ted Thomas and producer Kuniko Okubo, moderated by John Canemaker. This will take place on Thursday, August 27th, 7:30 PM at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, BAM Cinema 4, (30 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, NY).

Admission is free for Members of MoCCA. To rsvp, call (212) 254-3511.

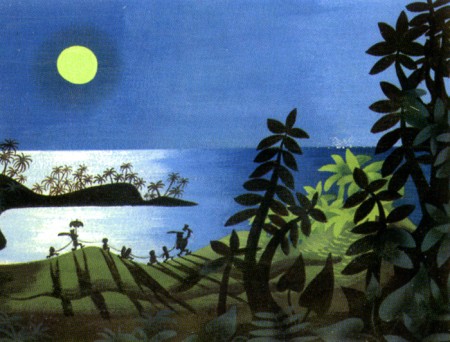

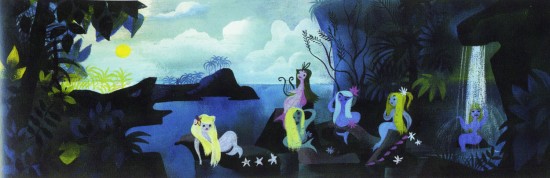

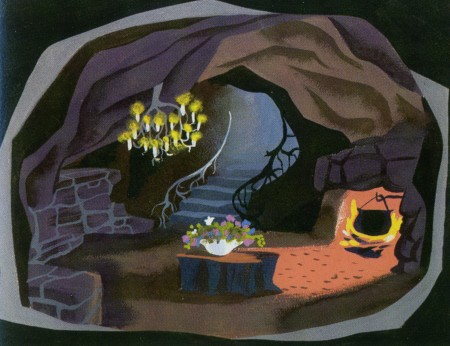

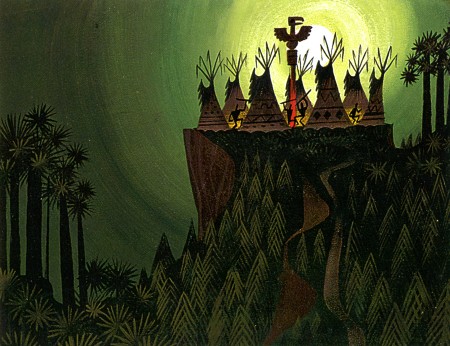

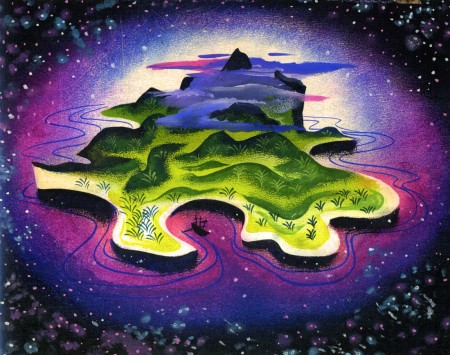

- In tune with the above comments and having posted, this past week, the wonderful 1940 model sheets from Disney’s Peter Pan (thanks to Bill Peckmann and his fine collection), I thought about the Mary Blair art for this film. Neither those model sheets nor Mary Blair’s art made it to the film.

- In tune with the above comments and having posted, this past week, the wonderful 1940 model sheets from Disney’s Peter Pan (thanks to Bill Peckmann and his fine collection), I thought about the Mary Blair art for this film. Neither those model sheets nor Mary Blair’s art made it to the film.

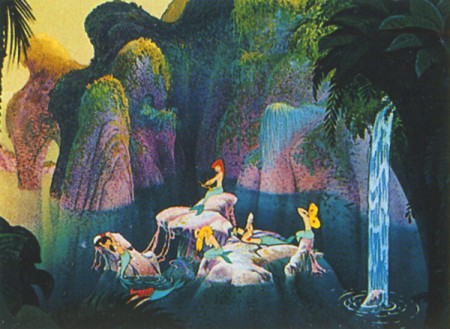

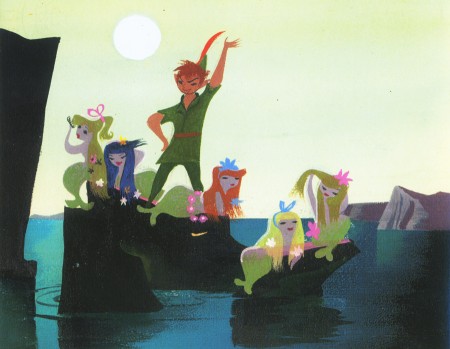

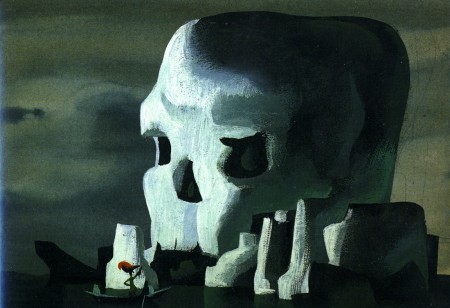

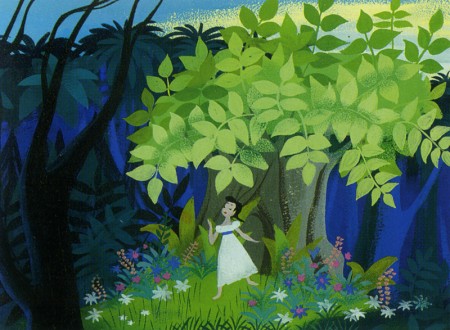

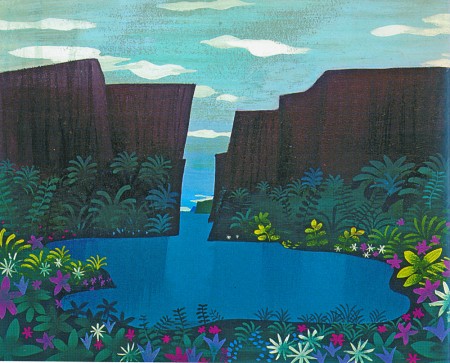

I thought, as a companion piece to those early model sheets, I’d post the Peter Pan illustrations in John Canemaker‘s fine book: The Art and Flair of Mary Blair. A number of these have been used to illustrate the new book, Walt Disney’s Peter Pan. They’re all attractive and modern in style. I think the film took the colors without the style and came up with a picture postcard look.

Here are Mary Blair‘s paintings:

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 10 Aug 2009 07:16 am

A Symphony of Models

- The illustrious NY animation designer/director, Bill Peckmann, is sharing a very large archive of material with this site, so I’ll be posting forever to get it up.

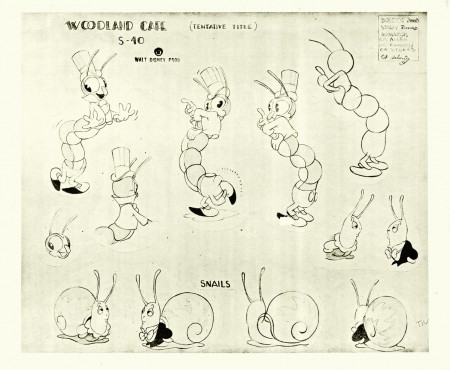

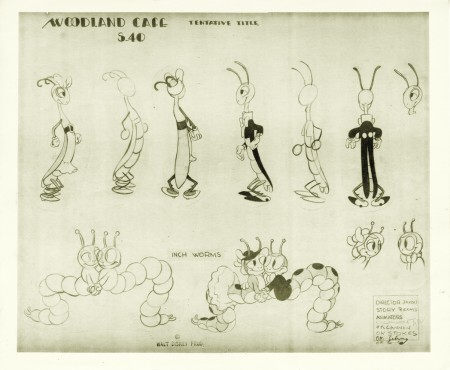

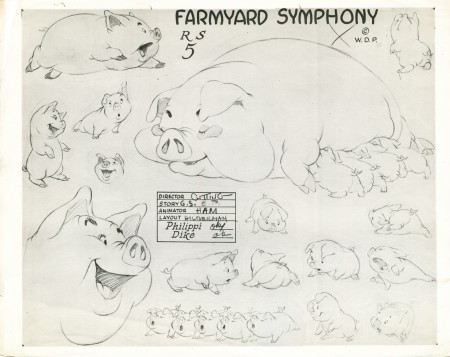

Let’s start with model sheets from some of the Disney Silly Symphonies. You’ve possibly seen some of these, but I like gathering them all in one post.

These are from three gems of films. Among the very best of the shorts.

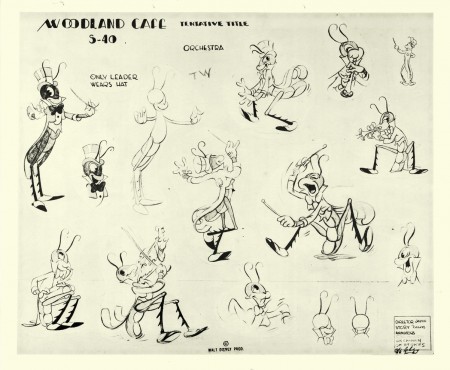

Woodland Cafe is a beauty released March 1937. these three model sheets are signed by Director Wilfred Jackson, animators Paul Allen, Johnny Cannon, Bob Stokes, Leonard Sebring, and storyman Dick Rickard. Other animators include: Cy Young, Izzy Klein, Dick Lundy, Charles Byrne, Jack Hannah and Ward Kimball. (Story supervision was actually done by Bianca Majolie and I’m not really sure the Sebring animated on this film.) Layout was by Terrell Stapp and John Walbridge.

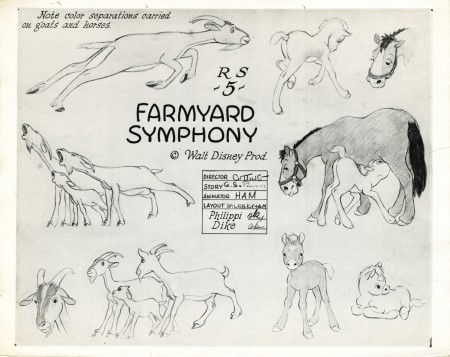

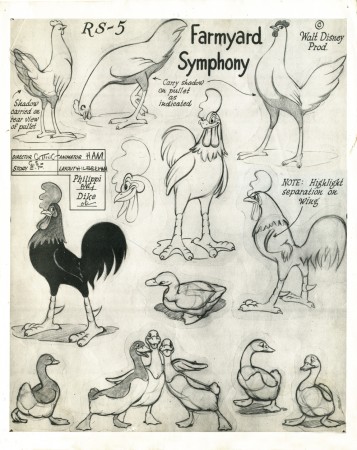

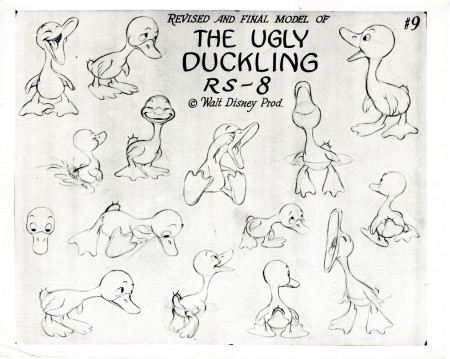

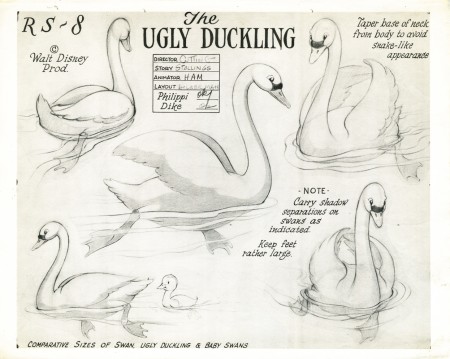

(Click any image to enlarge.)

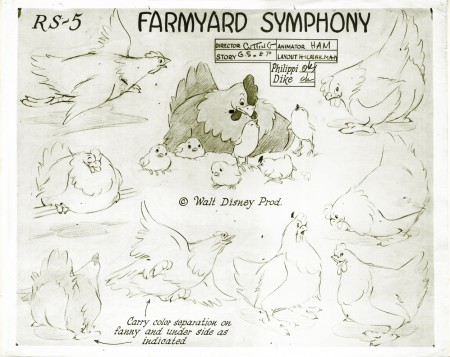

Farmyard Symphony was directed by Jack Cutting. George Stallings was the story supervisor. Ham Luske signed the sheets for the animators; he was probably the animation director. Animation was done by Eric Larson, Fred madison, John Bradbury, Ken Hultgren, Milt Kahl, Bernard Garbutt, Don Lusk, Paul Satterfield, Lynn Karp, John Sewall, and Paul Busch. Layout was by Dave Hilberman and Art Heinemann.

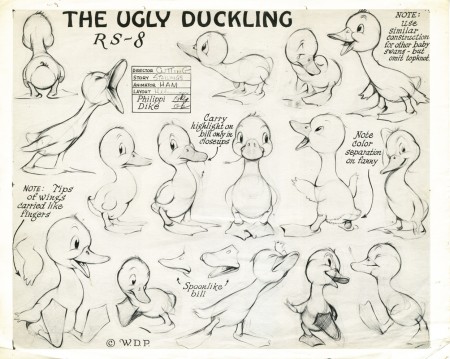

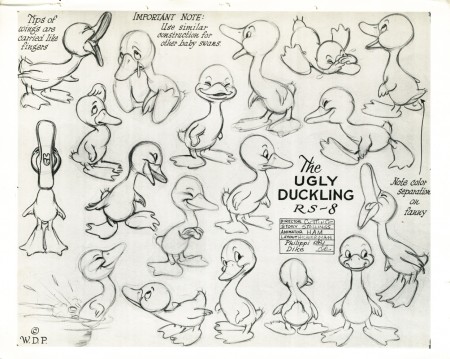

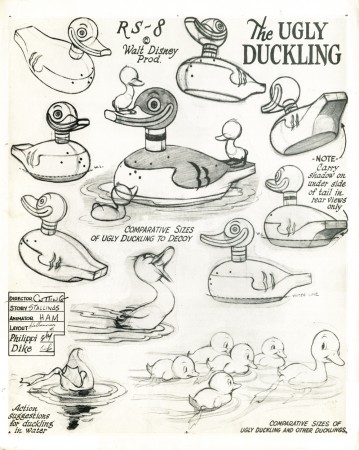

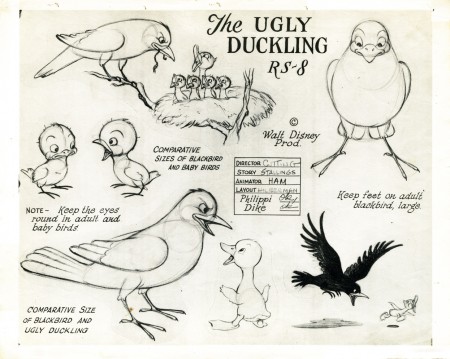

Rel;eased April 1939, The Ugly Duckling won the Oscar and stands out from a lot of the Symphonies of the period. Direction was by Jack Cutting and animation direction went to Ham Luske (which may explain why Luske signed the sheets for Farmyard Symphony as well. Layout was by Dave Hilberman and animation was by Eric Larson, Stan Quakenbush, Riley Thompson, Archie Robin, Milt Kahl and Paul Satterfield. George Stallings was the story director.

Many thanks to Bill Peckmann. More to come later this week.

.

Animation Artifacts &Disney &Models 07 Aug 2009 08:47 am

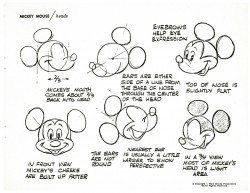

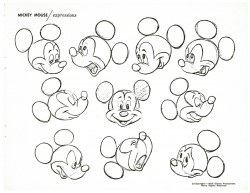

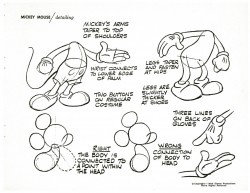

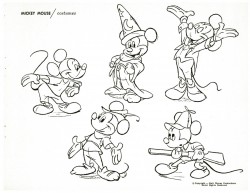

How to Draw Mickey

- When last we left off with the Disney lecture series on the principal characters – Mickey, Donald, Goofy, Pluto – I promised to conclude by posting the How To Draw series that were sold at Disneyland (late Fifties/early Sixties).

Go here to see the lecture series posts:

Mickey / Donald / Goofy / Pluto

So to continue with these How to Draw Books, I naturally start with Mickey. I’m not crazy about some of the drawings, but I guess it’s classic. This is actually a copy of the book that they gave out at the Disney/Lincoln Center event in 1973. They’re identical to the Disneyland books, though they lack the colored pages. (See Jenny Lerew‘s great site Blackwing Diaries for the original How to Draw Goofy book.

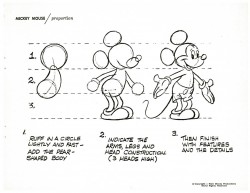

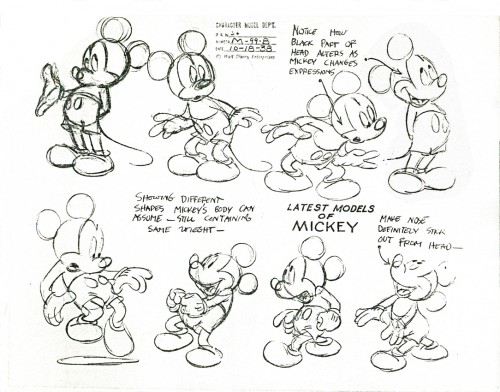

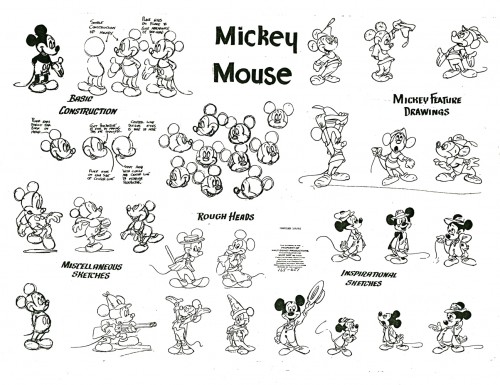

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge.)

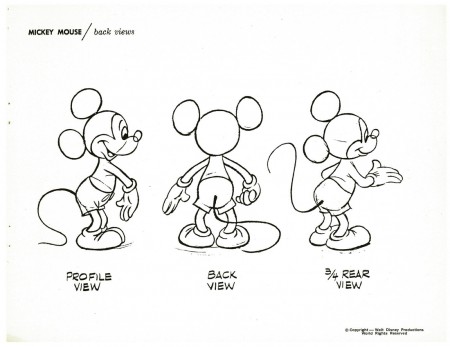

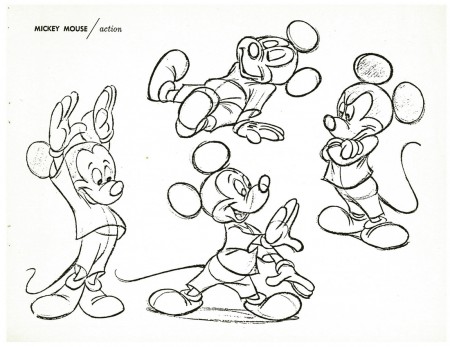

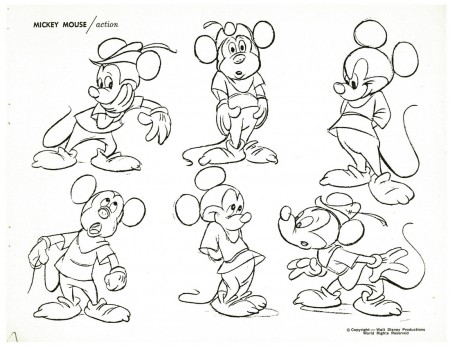

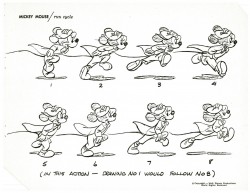

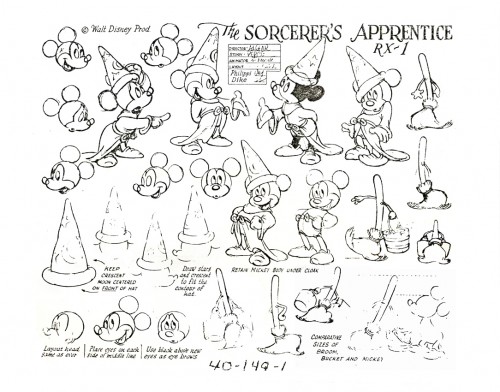

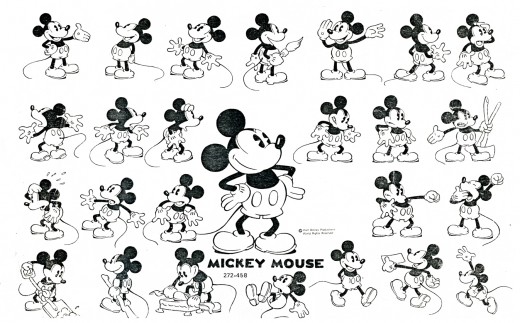

To put a little more zest into this post, here are a couple of Mickey model sheets I have. (copies of copies)

A mixed model with bits from a lot of other sheets.

This was probably put together in the Fifties.