Search ResultsFor "disney model sheets"

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 14 Feb 2011 09:18 am

The Laughing Gauchito – pt 2

____________________

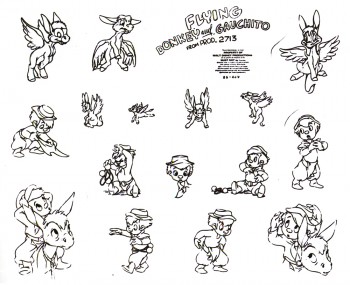

- As I wrote last week, The Laughing Gauchito was to be a stand alone short for Disney in 1942. It wa one of the first products of the group that had just returned from the South American trip. The film was to be part of a series that featured the “Little Gauchito”. They’d already completed one film. That film was originally The Flying Donkey, but they turned it over to the boy, and retitled it The Flying Gauchito, and it was added to The Three Caballeros.

- As I wrote last week, The Laughing Gauchito was to be a stand alone short for Disney in 1942. It wa one of the first products of the group that had just returned from the South American trip. The film was to be part of a series that featured the “Little Gauchito”. They’d already completed one film. That film was originally The Flying Donkey, but they turned it over to the boy, and retitled it The Flying Gauchito, and it was added to The Three Caballeros.

To read more about this series, I suggest you go to J.B. Kaufman’s excellent book, South of the Border with Disney.

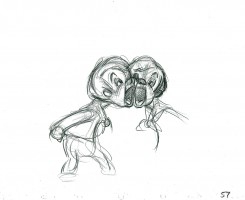

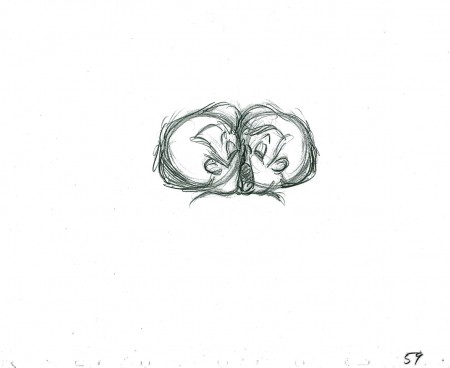

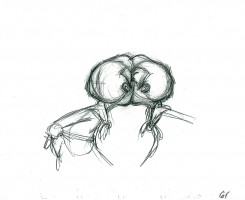

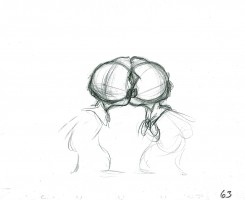

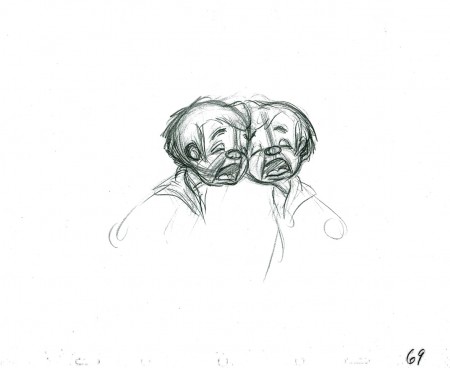

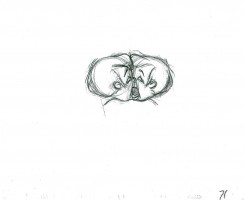

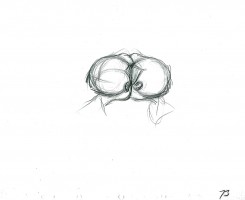

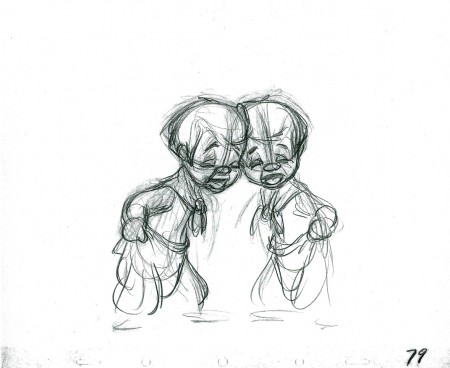

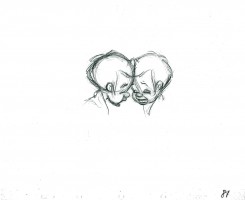

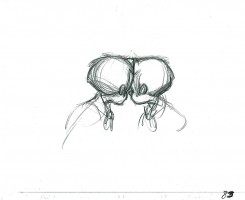

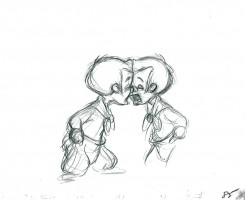

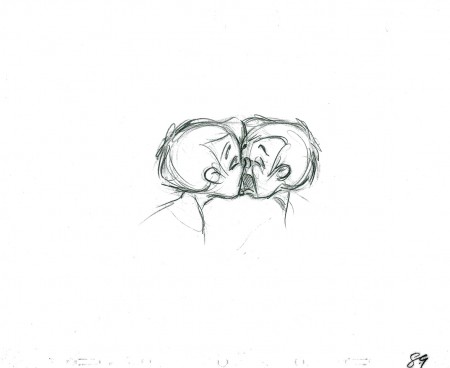

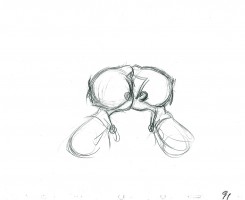

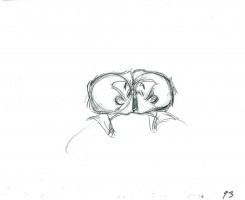

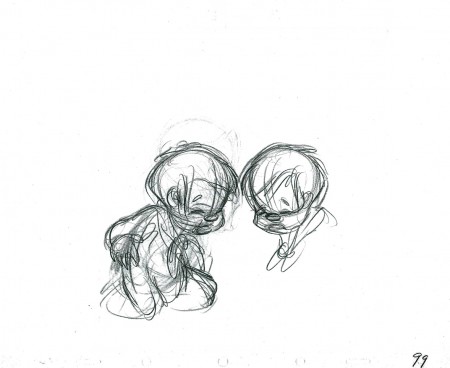

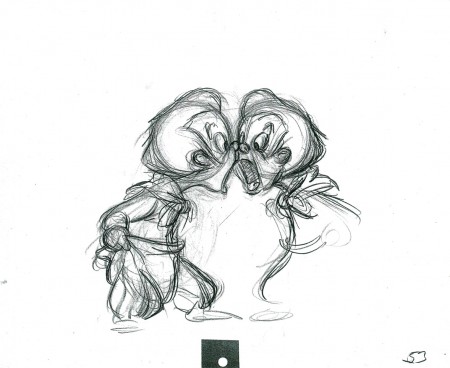

The story concerned itself with a boy who could not laugh. We see in this scene the boy trying to laugh in the mirror.

Ultimately, Disney, himself, put a stop to The Laughing Gauchito. Under the direction of Jack Kinney, some animation had already been done by Ollie Johnston, Bill Tytla and, particularly, Frank Thomas, to be well into the film. It took years to find some of the animation scenes in the morgue.

This dramatic scene is by Frank Thomas.

53

________________________

53

________________________

Here’s a QT of the scene with all the drawings from both posts to date.

Animation &Commentary &Disney 30 Nov 2010 08:26 am

Keane Posing

- Before posting this, let me tell you that I have all the respect in the world for Glen Keane. He’s one of the finest animators out there who consistently does original animation.

Last night I saw Tangled at a screening in 2D. I would have liked to have seen it in 3D, though EVERY review I’ve seen has put down the 3D experience saying that the glasses darken the movie to less than 60% of the brilliance on film. I doubt I’ll see it again for the 3D; if I do see it again it’ll be on DVD.

Last night I saw Tangled at a screening in 2D. I would have liked to have seen it in 3D, though EVERY review I’ve seen has put down the 3D experience saying that the glasses darken the movie to less than 60% of the brilliance on film. I doubt I’ll see it again for the 3D; if I do see it again it’ll be on DVD.

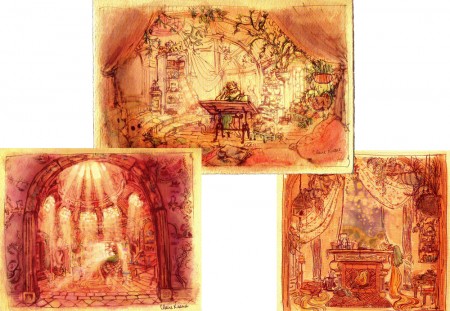

The history of the Disney studio. The film, itself, is basically a reworking of Beauty and the Beast (the magic flower, the bad male who has to be transformed into a good guy), Snow White (the wicked queen and the magic mirrors – two of them have to be broken), Cinderella (she cleans the tower for her wicked stepmother – or is this more of Snow White?), Sleeping Beauty (the horse with his own mind, the Princess awakens the sleeping Prince – or is this Snow White again?), The Little Mermaid (She looks like Ariel, the Little Mermaid with the hair that she just has to keep pushing back), Tarzan (the two lead characters skateboard over water and some paving, yet they don’t have skateboards). I could go on through some other films, but what’s the point?

Several of these female characters showed their spunk and advanced their Independence. In Tangled, Rapunzel goes after what she wants but doesn’t create her own fate, in the end. The male does. One expected it would be the wicked stepmother, but no, it’s the Prince … er Robber/Thief/Scoundrel. Inadequate. This is a film for 14 year old girls, and we see that they’ve seen it this past weekend, but they’re given the wrong version of the story.

The story in Tangled is smooth flowing, but crudely formed. It’s a mass of unbelievable material that rips apart one of the darker and great stories from the Brothers Grimm first published in 1812. The story is a nasty one which begins with a king, personally, stealing a plant from the witch’s garden to help his wife. She catches him on the spot and makes him promise his first born in payment.The king is RESPONSIBLE for his theft. Rapunzel moves to the tower and is protected from sex with her caging in the tower.

The film doesn’t use the hair very well. It is the sex that isn’t otherwise stated, and some symbolism should have entered the animation; it didn’t have to be obvious – it just had to be there. The incidental characters – all male seem to have bonded well, but we have no idea who they are or what their sexual preferences are. Again, the film seems unwilling to deal with the main subject of this great fairy tale. A stepmother trying to protect her daughter from the evils of the world. (Men!) Instead, this film is about ripping off Disney past. Yet we did see in Jeff Kurti‘s book on The Art of . . . that Rembrant was a major source of inspiration in the earlier days. Too bad too little of Rembrandt made it to the screen.

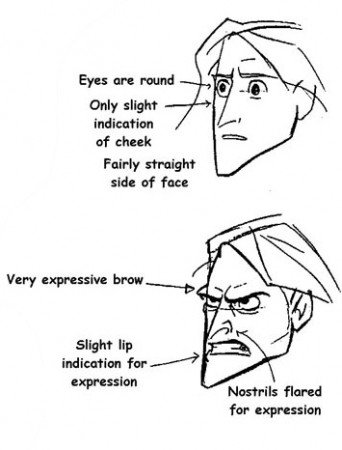

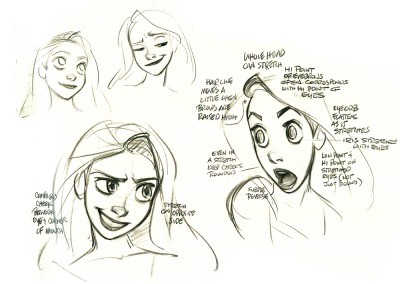

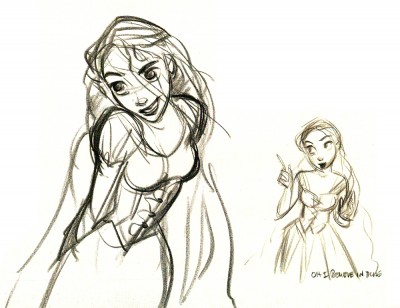

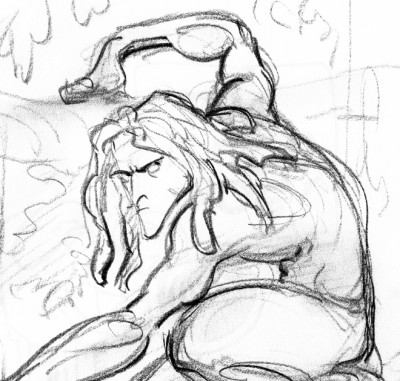

Just prior to going to this screening, I watched the first half of Tarzan on tv. Below, I’m going to post a number of drawings showing some clichéd poses by Glen Keane, but these poses don’t represent the animation he does on screen. He’s too good and sensitive an animator to show any clichés in the actual animation on screen. In fact, some of what he does is quite inspired. (Not the idea of Tarzan skateboarding through the trees without a skateboard. I expect the soles of his feet would be bloodied and damaged after trying it once, and I don’t think there’s scar tissue for it. It’s a small reality issue for me.) It’s just that these model sheet poses inspire clichés from lesser animators when they’re the poses.

Tangled is totally watchable (despite a couple of children running around the screening room, bored and loud). It’s just not good; story is everything.

Here are a bunch of drawings I culled from Raul Andres‘ blog, The Art of Glen Keane. I have to admit my purpose isn’t to showcase the art of Mr. Keane, but to express my disappointment with what I’ve found. It first became obvious to me with many of the drawings and models of his that were printed in the book, The Art of Tangled. Many of the poses he’s done since Beauty and the Beast have gone to the clichéd pose, and it’s disconcerting to me. Characters look like each other, and their facial postitions repeat the past. It’s a laziness in the drawing.

Look and compare drawings with this small sample. It took only minutes for me to compile them, and I could easily have kept going.

Tarzan 1

The problem, to me, is that Glen Keane has grown into this phase of reworking the same godawful poses. He has to come to grips with what he’s doing, and pay more attention it. There’s no excuse. It isn’t so obvious in his animation, just in his model sheets.

You wouldn’t be able to catch two poses from Frank Thomas, Milt Kahl or Ward Kimball that were so alike. There were no obvious clichés in their work.

Glen Keane is a remarkable artist and a brilliant animator. That is exactly why I have to take notice. There are many others aping what he’s doing in animation, and the kingdom is beset with endless clichéd poses. Let’s get it together, folks. Time to bring animation to a higher level.

Attitude has got to be a thing of the past. It’s rampant in Tangled, Toy Story 3 and to a lesser degree in Kung Fu Panda; it’s not obvious in How To Train Your Dragon. The independent films, The Illusionist and My Dog Tulip don’t settle into this type of posing. Strong, clear thinking artists dominate these two films.

Articles on Animation 04 Nov 2010 07:11 am

Animation Renaissance

- I enjoy rereading some of the articles in older magazines that talk about the “current state” of animation. We get to see, in hindight, what was thought of the industry during a time of change.

This article from Horizon Magazine, was written by John Canemaker in 1980, some 15 years before Toy Story and the serious explosion of cgi would take place in 1995. Many thanks to John for the article.

Animation. Renaissance ?

From Disney to independents,

animation continues to thrive.

By John Canemaker

Every few years the press alternately declares animation to be enjoying a “renaissance” or predicts the medium’s gloomy future. In the early 1970s, while Ralph Bakshi was riding a crest of popularity with the success of his cartoon features, Fritz the Cat (1972) and Heavy Traffic (1973), animation was rediscovered and pronounced “born again!” Last September, a dozen animators quit the Walt Disney studio and joined Aurora, a film production company started by three former Disney executives. Aurora is spending $7 million to produce a feature-length cartoon of a Newberry Award-winning children’s book by Robert C. O’Brien, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIHM. Ironically, Mrs. Frisby is a mouse, and, back at the Mouse Factory (as the Disney studio was nicknamed in the 1930s), the premiere of a new cartoon feature, The Fox and the Hound, had to be postponed for six months because of the departure of one-sixth of the animation department. With the recent Disney defections, the pundits (including the New York Times) lamented the “serious gap” in Disney’s creative ranks and noted that the animation industry (and, by implication, the art of animation) had been “long depressed.”

When a dozen animators quit Walt Disney, The Fox

and the Hound, Disney’s twenty-fourth animated feature,

had to be postponed for six months.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Further, the tacit assumption that Disney and the cartoon-film industry represent the

total contemporary animation scene—or even the most important part of it—is a benighted one.

Disney, to be sure, is a great and beloved name, synonymous with animation to the general public; but Disney today is only part of an international art form comprised of a dazzling variety of styles, techniques, and content. Animation continues to thrive and flourish as it has for more than eighty years, not only in industry-run cartoon studios that produce TV series, commercials, specials, and feature-length theatrical films, but in the experimental, personal alternative forms of motion graphics created by the swelling ranks of independent animation-film and -video makers.

Regarding the current Disney situation, it is important to know that it is not an unprecedented event. At least twice before, Disney artists have left the studio en masse — and each time the result was positive for both Disney and the animation industry. In 1928, for example, Walt Disney lost rights to a cartoon character named Oswald the Rabbit; at the same time he suffered the departure of some of his key animators. Oswald was replaced by a new character—Mickey Mouse—and Disney soon enlarged his staff with a corps of artists who, within a decade, advanced character animation to a new plane. Two of the 1928 defectors went on to form the Warner Brothers cartoon studio and, later, the MGM cartoon studio.

In 1941, a large contingent of employees participated in a strike at the Disney studio that crippled production for several weeks.

In 1941, a large contingent of employees participated in a strike at the Disney studio that crippled production for several weeks.

One effect of that walkout was Disney’s eventual diversification into areas other than animation, such as live-action features, nature documentaries, television, Disneyland, and Walt Disney World. The financial security derived from such variegation allows Disney to continue making animated features. Some of the 1941 strikers formed a new studio, United Productions of America (UFA), which revolutionized the design of studio cartoons by moving away from the ultranaturalistic Disney style toward bolder graphics rooted in modern art.

An illustration from_______ Animation production manager Don A. Duckwall revealed that

Le Cuchemar du Fantoche__ despite the recent walkout at Disney, “things are going

a 1908 short by Emile Cohl.__ along beautifully. There is a resurgence of enthusiasm for the

_______________________ product and the future.” Duckwall feels the defection has “cleared the air,” and the studio has promoted peopie who are ‘ ‘taking the responsibility and doing leadership work” on TheFoxandiht Hound feature. So confident is Ron Miller, Disney executive vice-president for creative affairs, that he has scheduled the long-awaited fantasy epic The Black Cauldron as the studio’s next animated-feature project.

“Another benefit of all the publicity about the ones who left,” explains Duck-wall, “is the tremendous number of portfolios being submitted by people wanting to join our animation training program. We now have eight trainees, which is a goodly number for us.” Paula Sigman, assistant archivist at the Walt Disney Archives, confirms the positive effect of the changeover; “Instead of sounding the death knell in the animation department, this has been like a breath of fresh air—to hear the rest of the young guys tell it. There’s a new feeling of unity, of openness and willingness to communicate, of ambition. And although they’re pushed back on Fox and Hound, they’re quite excited.”

Don Bluth, the forty-two-year-old leader and spokesman for the animators who left Disney, said the resignations were “trig- ‘ gered by a dispute over training practices and artistic control.” He plans to make their feature, Mrs. Frisby, in the Disney mode (“It’s the style we love!”), but claims “the content will be different.” Mike Barrier, editor of Funnyworld, a periodical devoted to animation and comic art, has commented that “the real reason the group ! left is not that they want to go beyond what Disney has already done, but because the present studio is not ‘Disney’ enough!”

It is too early to tell if Bluth and company will succeed with their first solo venture and go on to take animated features into areas uncharted by Disney or if the Disney studio itself can succeed with this new creative challenge. The missing factor this time around is, of course, the powerful healing presence of Walt Disney himself; but certainly the competition of the two studios in the area of animated features is a healthy one for animation.

Otto Messmer (second from left) created Felix the Cat

at the Pat Sullivan studio in NY around 1919.

Computers such as Computer Creations “Videocel”

technique are being used today to cut production costs.

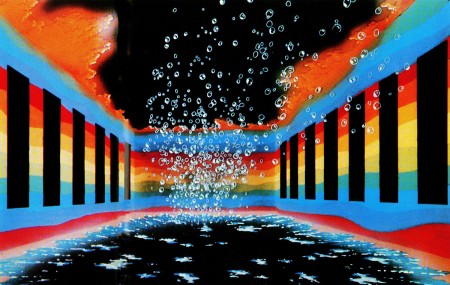

The last decade has seen an astonishing increase in the number of animated features produced by studios other than Disney. This trend can be traced back to The Yellow Submarine (1968) directed by George Dunning in London. A still-fresh, pop-art fairy tale of our times, starring the magical Beatles, it is a milestone film that redefined the stylistic and narrative borders of animated features. It also tapped a lucrative nontraditional cartoon-feature market composed of young singles and teenagers as well as attracting the usual family-kiddie audience.

Ralph Bakshi confirmed the existence of this “other” audience with his two aforementioned X-rated cartoons, which, though sloppy structurally, were compel-lingly earthy and poetic. They explored darker, more sensual themes and emotions than Disney dared to. Of a dozen animated features released in the last three years, several aimed toward a wider audience: Watership Down, Lord of the Rings, Allegro Non Troppo, and Dirty Duck. Internationally, there are about twenty animated features currently in production or in the planning stages.

While it can take two to three years to produce a ninety-minute animated feature, the half-hour Saturday morning children’s series on television devour huge amounts of screen footage each week. Abhorred by parent’s groups, but passively tolerated by children, Saturday morning “kidvid”—or “illustrated radio,” as veteran animator-director Chuck Jones terms it—clones on season after season with formula mediocrities such as Casper and the Space Angels, The New Schmoo, Godzilla, Fangface, Scooby’s All Stars, etc.

But in addition to the series, each year brings a number of animated specials to television. With higher per-show budgets and longer preparation time than for series, the specials’ quality level is higher. Look, for example, at the Peanuts specials, The Doonesbury Special, Everybody Rides the Carousel, The Pumpkin Who Couldn ‘t Smile, and The Hobbit, among others. As if this were not enough to keep animators busy, the PBS educational series (Sesame Street, Electric Company, 3-2-1 Contact) solicit brief, informational, animated spots from many studios and individual film makers. TV commercials often use animation when their selling approach delves into the fantastic, as in the surreal Levi’s spots by Robert Abel & Associates and the virtuoso, action-packed Jovan: The Power by Richard Williams Studio.

Today, animation is not just for kiddie cartoons.

The Oriental Nightfish was a short developed to

be used in the concerts of the rock group, Wings.

The above outlets for animation, theatrical features, and television are dominated by “the industry”—films made by a group of artists and craftspeople in a studio using mostly cartoon designs. It is this work that is most accessible to the general public, both actually and aesthetically. But there is another force working in animation, much less well known but gaining each year in terms of recognition and in avenues of distribution and exhibition. This is a large, vital international network of independent animation-film and -video makers who, freed from profit-motive considerations, explore alternative ways of communicating, interpreting, and expressing themselves and the world through animation. Many work for years on a short film; some subsist on canvas, or a sculptor to clay.

“Because it depends so heavily on technical expertise, we believe the medium of animation enters into the realm of art only when it has a strong personal imprint,” said George Griffin, a leading experimentalist. Griffin, whose inventive films explore the “act of art-making” in a variety of techniques from flip-books to Xeroxed graphics, last year privately published an anthology of new American independent animators.

Titled Frames, the book represents the work of more than seventy animators in this country alone. Their techniques and graphic signatures are lavishly diverse: some artists work in collage (Frank Mouris), others use optical printing (Peter Rose, Anita Thacher), or drawing on film (Steve Segal), direct three-dimensional manipulation (Caroline Leaf, Eli Noyes), rotoscoping (Mary Beams), drawing on paper (Kathy Rose, Dennis Pies), and “cel” animation

(Suzan Pitt, Sally Cruickshank).

To the independents, Griffin notes, “experimental film is not about what a work looks like, but what it does. How it invents its own form, makes its own rules, while stretching the definition of the medium of animation.”

Slowly, the work of these individualistic artists is reaching a larger public. The 1978 New York Film Festival featured a showcase of new animation, as did the USA Dallas Film Festival and the Los Angeles Film Exposition. Independent animators from around the world consistently win top prizes in animation festivals in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, Annecy, France, and Ottawa, Canada. Cable and public television stations book these works, thus introducing them to a wide scope of interested viewers. For two years PBS sponsored the International Animation Film Festival series, which booked many nontraditional animated films. A feature-length compilation, The Fantastic Animation Festival, was distributed theatrically and found particular favor on this country’s college campuses. More and more nontheatrical distributors, who sell and rent films to schools, universities, and library collections, are responding to their patrons’ interest in the new animation and are signing many experimental animators to contracts.

A color model from the pop-art animated feature

The Yellow Submarine (1968) indicated to the

opaquers which colors to use in the final frames.

In the beginning, naturally, all animation was experimental. Although no one knows who first discovered the magic inherent in the camera’s ability to shoot single frames of film, three pioneers defined the animation medium by experimenting and inventing the basic tools still in use today. James Stuart Blackton, a cartoonist-reporter for the New York Evening World, made Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906 and used animation to promote himself and his film company, Vitagraph. The Parisian Emile Cohl made or contributed over 250 animated sequences starting in 1908; his series, The Newly weds, made in America and based on a popular American comic strip, was very influential in identifying the animated-cartoon genre with the weekly comic strip in the public’s mind. Winsor McCay, the most gifted cartoonist-draftsman of his age, tirelessly explored the possibilities of line and motion in his ten films including Little Nemo (1911) and Gertie the Dinosaur (1914)) and promoted animation on his chalk-talk vaudeville tours.

It was in 1914 that American cartoonist John Randolph Bray turned animation into a business. Bray, who might be termed the Henry Ford of animation, organized a staff of specialists doing assembly-line tasks in cartoon studios. He cannily took out patents on certain work- and time-saving inventions (the most important being clear Celluloid acetate sheets called “cels”) which enabled large numbers of films to be produced in series. Thus began the industry of animation, the mass production of cartoon films starring a parade of internationally famous characters. Often the characters came from the newspaper strips, like Mutt and Jeff. But Felix the Cat, created by Otto Messmer at the Pat Sullivan studio in New York circa 1919, was made for the screen —the first creature to express an individuality in drawings that move. Felix’s unique design and, most important, his personality profoundly influenced Walt Disney’s famous animated rodent.

The experimentalists continued to work by themselves creating films that widely diverged from the commercial mainstream. Often the influence of the avant-garde was felt in the studio product, but it was adapted into the “accepted” version —reduced for the conditioned taste of the public who rarely experienced the strong individuality of the original source. (A prime example is the preliminary work the German abstractionist Oskar Fischinger contributed to a sequence in Disney’s Fantasia [1940].) Strong, beautiful, short films of singular vision were made by animators in Europe during the period 1920-1935 and in America in the 1940s and 1950s. Among these animators were Len Lye who painted directly onto film, Lotte Reiniger who used cut-out silhouettes, Alexander Alexeiff who worked in pinscreen, John Whitney with his computer works, and Jordon Belson whose specialty was video projects.

Interest in animated films has been enhanced by a wave of printed supporting material: in the last five years, scores of periodical articles and eighteen books on all aspects of animation have been published. Some of the books deal with cartoon nostalgia (The Fleischer Story), some focus on technology and technique (Visual Scripting), others on a particular genre (Puppet Animation in the Cinema), or historical perspective (Experimental Animation: An Illustrated Anthology). Six new books in the works aim toward publication within two years.

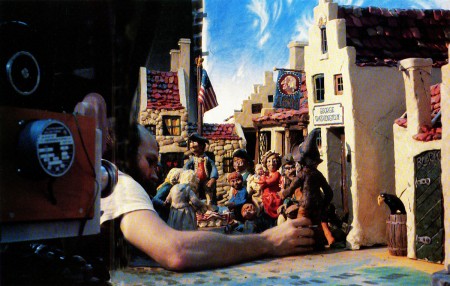

Oscar-winning Will Vinton, one of today’s innovative animators,

adjusts characters from Rip Van Winkle, a half-hour clay animation.

The current issue of the American Film Institute’s Guide to College Courses in Film and Television shows that more than sixty major American colleges feature animation workshops and/or film-tape appreciation courses in their curriculum. Most celebrated is the California Institute of the Arts, which divides its animation work-shops into an experimental group under veteran designer Jules Engel and a character-animation section headed by Disney shorts-director Jack Hanna. Many of En-gel’s students have become some of today’s most exciting independent animators and several of Hanna’s students have found their ways to jobs at Disney or other cartoon studios.

The cross-pollination of ideas gained by the proximity of the two Cal Arts animation courses is a good omen and symbol for the future of animation. The art today is undeniably vigorous and varied; computers are being developed to enhance productivity and cut production costs (such as Computer Creation’s “VideoCel” technique). The growing visual sophistication of audiences and the international exchange of ideas between the avant-garde and the industry, the new technology outlets for films and tapes, such as video-disks and home-tape consoles, make the future of animation exciting and unlimited.

- Who’s Watching Cartoons?

Most viewers are children, but there is a healthy contingent of adults, particularly for reruns of old theatrical shorts.

Tim Roberts, head of creative services at New York’s Channel 5, notes that his station receives a “steady number of phone calls from adult viewers” inquiring as to the titles of the shorts shown in the daily series. “Some people want to see a certain favorite, like Bugs Bunny or Woody Woodpecker, but most of the callers have videotape machines and want to tape certain films to add to their cartoon collections.”

Last November Channel 5 presented a half-hour Cartoon Film Festival for one week in prime time (8 P.M.), with interesting viewer results. Diane Sass, vice-president of marketing and research at Channel 5, consulted the Arbitron report, a book of TV viewer demographics and noted that the festival received a ten rating, which she said is “very good. The usual programming in that time slot is a game show, ‘Crosswits,’ which usually pulls a six to seven rating.” More interesting was the breakdown of viewers according to age. The Cartoon Festival, said Sass, “had a total viewing audience of 1,217,000. Of that 438,000 were kids, 225,000 were teenagers—age twelve to seventeen—and the majority of viewers, 554,000, were adults, eighteen-plus.”

A guest fellow at Yale University teaching animation history, John Canemaker is the author of The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy—An Intimate Look at the Art of Animation: Its History, Techniques and Artists and makes animated films and documentaries about animation.

Articles on Animation &Richard Williams 26 Oct 2010 07:58 am

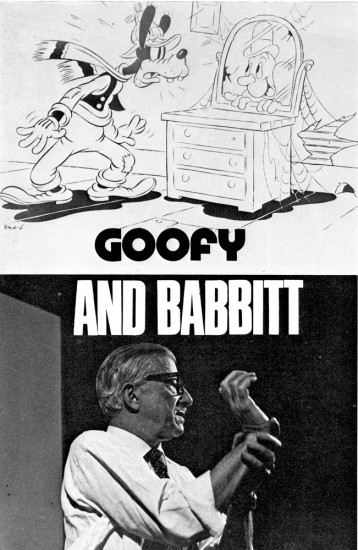

Goofy and Babbitt

- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

You can see the film on YouTube, here.

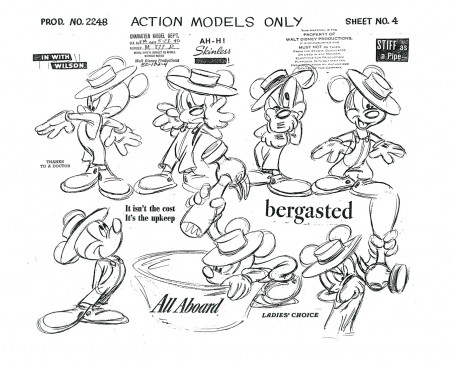

I previously posted the first half of this article with all the Goofy model sheets that it accompanied. You can see that here.

(The original, unfortunately, contains the “N” word instead of “coloured boy” as this edited version offers.)

.

Goofy and Babbitt

by Art Babbitt and Richard Williams

.

Two of the great artist-animators of the golden years of the Disney Studios, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick, were working and teaching at the Richard Williams Studios in London last summer. To parallel Babbitt’s 1934 character analysis of Goofy, which has not previously been published, Richard Williams gives an impression of the animator himself.

Two of the great artist-animators of the golden years of the Disney Studios, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick, were working and teaching at the Richard Williams Studios in London last summer. To parallel Babbitt’s 1934 character analysis of Goofy, which has not previously been published, Richard Williams gives an impression of the animator himself.

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE GOOF—JUNE 1934

In my opinion the Goof, hitherto, has been a weak cartoon character because both his physical and mental make-up were indefinite and intangible. His figure was a distortion, not a caricature, and if he was supposed to have a mind or personality, he certainly was never given sufficient opportunity to display it. Just as any actor must thoroughly analyse the character he is interpreting, to know the special way that character would walk, wiggle his fingers, frown or break into a laugh, just so must the animator know the character he is putting through the paces. In the case of the Goof, the only characteristic which formerly identified itself with him was his voice. No effort was made to endow him with appropriate business to do, a set of mannerisms or a mental attitude.

It is difficult to classify the characteristics of the Goof into columns of the physical and mental, because they interweave, reflect and enhance one another. Therefore, it will probably be best to mention everything all at once.

Think of the Goof as a composite of an everlasting optimist, a gullible Good Samaritan, a half-wit, a shiftless, good-natured coloured boy and a hick. He is loose-jointed and gangly, but not rubbery. He can move fast if he has to, but would rather avoid any over-exertion, so he takes what seems the easiest way. He is a philosopher of the barber shop variety. No matter what happens, he accepts it finally as being for the best or at least amusing. He is willing to help anyone and offers his assistance even where he is not needed and just creates confusion. He very seldom, if ever, reaches his objective or completes what he has started. His brain being rather vapoury, it is difficult for him to concentrate on any one subject. Any little distraction can throw him off his train of thought and it is extremely difficult for the Goof to keep to his purpose.

Yet the Goof is not the type of half-wit that is to be pitied. He doesn’t dribble, drool or shriek. He is a good-natured, dumb bell what thinks he is pretty smart. He laughs at his own jokes because he can’t understand any others. If he is a victim of a catastrophe, he makes the best of it immediately and his chagrin or anger melts very quickly into a broad grin. If he does something particularly stupid he is ready to laugh at himself after it all finally dawns on him. He is very courteous and apologetic and his faux pas embarrass him, but he tries to laugh off his errors. He has music in his heart even though it be the same tune forever, and I see him humming to himself while working or thinking. He talks to himself because it is easier for him to know what he is thinking if he hears it first.

His posture is nil. His back arches the wrong way and his little stomach protrudes. His head, stomach and knees lead his body. His neck is quite long and scrawny. His knees sag and his feet are large and flat. He walks on his heels and his toes turn up. His shoulders are narrow and slope rapidly, giving the upper part of his body a thinness and making his arms seem long and heavy, though actually not drawn that way. His hands are very sensitive and expressive and though his gestures are broad, they should still reflect the gentleman. His shoes and feet are not the traditional cartoon dough feet. His arches collapsed long ago and his shoes should have a very definite character.

Never think of the Goof as a sausage with rubber hose attachments. Though he is very flexible and floppy, his body still has a solidity and weight. The looseness in his arms and legs should be achieved through a succession of breaks in the joints rather than through what seems like the waving of so much rope. He is not muscular and yet he has the strength and stamina of a very wiry person. His clothes are misfits, his trousers are baggy at the knees and the pant legs strive vainly to touch his shoe tops, but never do. His pants droop at the seat and stretch tightly across some distance below the crotch. His sweater fits him snugly except for the neck, and his vest is much too small. His hat is of a soft material and animates a little bit.

It is true that there is a vague similarity in the construction of the Goof’s head and Pluto’s. The use of the eyes, mouth and ears are entirely different. One is dog, the other human. The Goof’s head can be thought of in terms of a caricature of a person with a pointed dome—large, dreamy eyes, buck teeth and weak chin, a large mouth, a thick lower lip, a fat tongue and a

bulbous nose that grows larger on its way out and turns up. His eyes should remain partly closed to help give him a stupid, sloppy appearance, as though he were constantly straining to remain awake, but of course they can open wide for expressions or accents. He blinks quite a bit. His ears for the most part are just trailing appendages and are not used in the same way as Pluto’s ears except for rare expressions. His brow is heavy and breaks the circle that outlines his skull.

He is very bashful, yet when something very stupid has befallen him, he mugs the camera like an amateur actor with relatives in the audience, trying to cover up his embarrassment by making faces and signalling to them.

He is in close contact with sprites, goblins, fairies and other such fantasia. Each object or piece of mechanism which to us is lifeless, has a soul and personality in the mind of the Goof. The improbable becomes real where the Goof is concerned.

He has marvelous muscular control of his bottom. He can do numerous little flourishes with it and his bottom should be used whenever there is an opportunity to emphasise a funny position.

This little analysis has covered the Goof from top to toes, and having come to his end, I end.

ART BABBITT

.

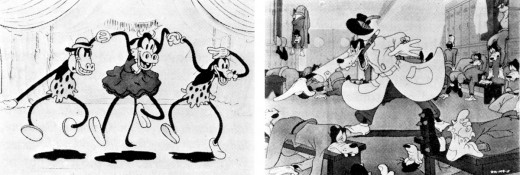

‘Orphans’ Benefit’ (1934). The Goof after Babbitt: ‘How to Play Football’ (1944)

.

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE ANIMATOR—JANUARY 1974

.

He is a funny mixture. He has the bearing of a Marines sergeant (which he was during the war, after leaving Disney following the strike in which he was the principal figure); but he has the mind of a Viennese doctor—which is what he wanted to be. In his youth he always wanted to go to Vienna and study psychiatry; but he couldn’t because he was a poor boy from Iowa with relatives to support. So he went to New York and taught himself to be a commercial artist; and gradually got into animation—starting, I think, through Paul Terry.

Arriving at Disney, he was one of four animators on Three Little Pigs; and of course that was the great breakthrough in personality animation. Then he animated Goofy, and worked on shorts in preparation for Snow White. In the first Disney feature he animated the Queen where she was beautiful, up to the point where she is transformed into the hag. In Pinocchio he did most of the animation of Gepetto, and Gepetto almost looks like him. He had that sort of versatility, to characterise the horrid queen or the sentimental wood-carver. Then in Fantasia he did primarily the mushroom dance; but he was animation director on a lot of other material. On Dumbo he was a supervising animator.

The strike came in 1941. Babbitt had had a personal confrontation with Disney over the low payment of assistants; and Disney ill-advisedly fired him, giving as a reason his u-nion activities. This was directly in contravention of the Wagner Labor Relations Act, and the

U-nion took a strike vote. Babbitt fought Disney through all the courts; and they were obliged to reinstate him, for an uncomfortable period during which Disney would pass him in the corridor without speaking or even looking at him. He stood it for a year; then he quit.

After the war he and Natwick were with Hubley at UPA – Art did most of Rooty Toot Toot. Later he was with Hanna and Barbera. I had heard about him for years before I finally came to meet him. He had seen some of our work, and though he’d not exactly liked it (it was pretty slick) had decided that ‘here are some people trying to do an honest job, and that’s the first time I’ve seen that in ten years.’ He wasn’t all that impressed, but he went to the heart of it.

It turned out he was very interested in teaching people. He was thinking of writing a book to instruct people; and he’d done a course at U.S.C. of which we had copies of students’ notes. As it happened he had a fire at his house and all his own lecture notes were burned. So we were able to send him these student notes. He said they were all wrong; but it was something. Then finally I asked him straight out if he would come over and teach us, because we had gone as far as we could go on our own.

He is a great teacher. He has an astonishing lucidity. Most animators are completely incoherent; they are unable to tell you what they are doing. But Art doesn’t have any difficulty in showing you how a thing works. He just says: ‘Did you notice that that worked because such and such . . . and Hubley did this thing this way?’ And when Art says something is wrong, he’s invariably right—if you want it to work. He’ll say: ‘If you want the wheel to go round, this is the way to make it go round. This is the way to make a cypher for making it go round. And this is another way they used to give the impression of it going round. And your problem is that you are to do it with square wheels.’ He is completely eloquent. I’m sure that at Disney they created a language about what they were doing; and I’m equally certain that it was he who largely gave a verbal form to it, so that the others could understand it. He has a surgeon’s mind; which, I gather, Disney had also.

When he taught in our studio he insisted that people take the course. He started off by saying: ‘Please, in my lectures, do not be British. Be crude, be revolting; ask stupid questions. Please do not be polite; otherwise I’m wasting my time.’ He’s as tough as nails; yet it literally hurt him when someone couldn’t get a thing right, couldn’t understand it. Then when they got it right, he would dissolve in warmth. His patience was beautiful.

He knows so much about everything— about symphony construction, about the visual arts, about everything to do with the medium. He once decided he would teach himself to play the piano. He’s the one in the famous Disney story —when he was learning to play the piano, and Disney said, ‘What are you—some kind of fag or something ?’ He hated Disney for that, because he wanted to understand music to apply it to animation. He knew that Fantasia or something like it was inevitable.

On the course he told us: ‘An animator must possess a curiosity about everything that exists or moves . . . must be a student of everything that might or does exist. From the shiver of a blade of grass—affected by an invisible breeze—to the behaviour of a starving hobo eating the first steak he has had in years. From a baby, tentatively trying to walk for the first time—to an elephant doing the can-can.’

I just saw Fantasia again and the Dance of the Mushrooms; and he was doing things there—treating perspective as a subsidiary action—that no one else was doing at the time. And he does not do it by feel, as I might, but because he’s worked it all out and analysed it. On the course he would say: ‘This is the cliché. This is the formula. And this is how to break it.’ He would set up the rules and then make you bust them.

And as well as the analytical capacity and the intelligence is the ability to start from basics—to deal with the most minute detail. He knows how the labs process the material; the way celluloid is made, the way the pencil is made. People who know that kind of thing don’t usually have artistic ability into the bargain. The ability to discern basics extends to his gift for statements that seem entirely simple and yet reveal vital things one often has not recognized : ‘We must learn to create movements if necessary that are caricatures of reality— but done with such guile they are always convincing.’ ‘We must expand our sense of caricature—to realise that we are not simply exaggerating external appearances— but more important, the inner character, the mood, the situation. A caricature is a satirical essay, not just doubling the size of a bulbous nose.’

A Babbitt scene from Williams’ Cobbler and the Thief.

My portrait is idolatry, maybe; but how do you not idolize someone who after more than forty years work in his and your medium still can find it ‘wonderful, exciting, exacting … A medium that has barely been discovered, let alone explored. A medium that can be an art form that encompasses practically all other art forms. A medium that can gratify aesthetically, that is not earth-bound, that can be an invaluable aid in teaching everything from elementary chemistry to the Theory of Relativity.’

RICHARD WILLIAMS

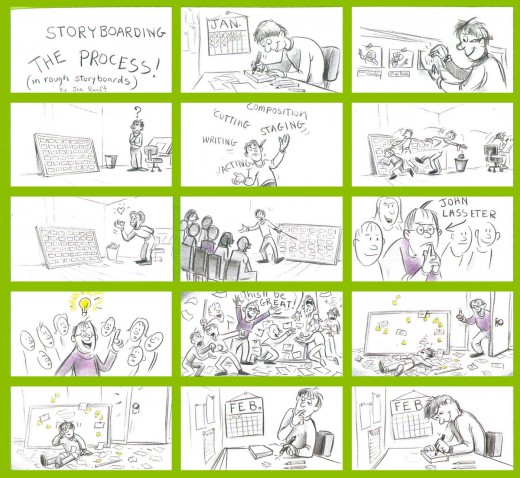

Books &Commentary &Disney &Story & Storyboards 02 Aug 2010 10:08 pm

Joe and Joe

- Today is the day that John Canemaker‘s book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft officially hits the stores. I urge you to take a look and go for it. The book is great.

- It was about nine months ago that John Canemaker let me read the galleys of his new book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft. I’d been aware of the book for a couple of years now, and whenever I’d heard John talk about it I wondered how the two guys fit in together to make a book. When I was handed the galleys, I moved slowly ahead with some trepidition.

- It was about nine months ago that John Canemaker let me read the galleys of his new book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft. I’d been aware of the book for a couple of years now, and whenever I’d heard John talk about it I wondered how the two guys fit in together to make a book. When I was handed the galleys, I moved slowly ahead with some trepidition.

I basically knew who the two Joes were from my reading and my NY attempts to keep up with the Hollywood system. Joe Grant was an old timer who’d dominated the Disney modelling department (the only time there was a department exclusively for model sheets), and he’d come back to act as one of the wizened artists helping to shape the new “Renaissance” in the animation community. Joe Ranft was one of the key CalArts guys who’d gone through the Disney system on his way to Pixar where he helped to shape that studio. There’s no doubt he was key to Toy Story, A Bugs Life and Monsters Inc.

What connection would John Canemaker have for tying these two together? Would that connection be enough to fill a book?

Of course, all such conjecture was stupid on my part. The book, as it turned out, is one of John Canemaker‘s finest, and that’s saying a lot. John, after all, is one of the best of our animation historians. His material is well researched, his facts are accurate, and his information is always pertinent and absorbing. He is also a good writer. He tells a story and reveals his information as any good writer would. There’s a solid construction to all of his books, and he lets you into the book in a comfortably relaxed way so that you’re absorbing the story and facts all together, and you are pulled into the book. This is the greatness of Two Guys Named Joe.

As for the connection, John explains that well. Not only, of course, within the book, but he had this succinct statement to make in an interview with Amid Amidi: “I saw the possibility of an overview of the history of storytelling at Disney and Pixar through a very human story of two artists straddling the 20th and 21st centuries.” And that’s exactly what John uses the book to do. He wants to really upchuck the earth of the story departments of both Pixar and Disney, and he does a good job of it.

I’ve now read the book twice. Once in galley form, once in final book form. The book is a rich-looking item full of the finest artwork from storyboards, printed material and developmental art. It’s a gorgeous book.

However, the real gold is in some of the writing and treasured bits that John has dug up to support his material. Here, for example is a small piece about Alice In Wonderland’s story development:

A March 15, 1939, story conference transcript reveals Walt’s frustration with the project:

A March 15, 1939, story conference transcript reveals Walt’s frustration with the project:WALT: (To Joe) Have you been through A//ce in Wonderland lately?

JOE: No. I’ve been through the script though. I think there are some pretty good situations in this.

WALT: Yes, and some, too, that are not so good.

JOE: I like the stuff on the disappearing cat—swell possibilities in that.

WALT: Yes. Let’s see. What are the good situations?

JOE: The tea party stuff is good.

WALT: Yes, the tea party is to me the best. . . You

know, I think we’re missing a hell of a lot in the stuff that is our medium. . . everything isn’t dialogue. Talk, dialogue business that depends on dialogue, hinges on dialogue.

Disney then tore into an unfortunate writer named Dana Coty.

WALT: I’m saying that to you because I think maybe

you’re the one that’s responsible for a lot of silly business that has no basis on anything funny.

DANA: Well, in the duchess’s house, I wrote that very loosely to begin with, Walt.

WALT: I don’t give a damn how you wrote it. It’s what we’re driving at. If it hasn’t got a basis for something funny, don’t write it! There’s no use writing the thing and then alibi-ing for it afterwards. It just throws us off the, track. Don’t just write anything to fill up some pages. We had the same criticism, the last time we were together.

John uses this anecdote to not only say something about Disney, himself, but the way he communicated with Grant and the hostility he might display for others. He did not mince words or waste time where he thought it was wasted. They were trying to solve the problms they saw in Alice In Wonderland, but we learn that Grant, Huemer and others felt that Disney was the problem. They felt he didn’t quite understand the Victorian humor of the original and tried to gag it all up. It’s just one wonderful excerpt dug deep in the book.

Another gem of a sequence involves Joe Ranft. It’s the point just when the Pixar artists are trying to sell Toy Story to the Execs at Disney. They’re doing everything in their power to make the film story good while placating the Disney people, and they’re having a hard time of it.

- Disney insisted the production move to Los Angeles so the studio could oversee things. “And give us more notes,” Ranft lamented.

Lasseter, whose “heart was broken,” begged for a two-week reprieve to turn things around. After obtaining Disney’s skeptical permission, Lasseter, Ranft, Docter, and Stanton resolved to “make the movie we want to make!”

. . .

The process included writing, gathering more material, constant meetings, weeding out, refocusing, and . . . more meetings. “Two or five heads are better than one,” Ranft believed. “If you can work together without killing each other, you an accomplish a lot.”

Going forward, Pixar gladly accepted notes from Disney and welcomed participating in brainstorming sessions with their artists. “But,” Ranft said, “we’d go away and really think about [the notes]. A lot of times we’d go, ‘No. Here’s the real problem!’ And it was even deeper than the notes. ‘And here’s how we’re going to fix it.’”

Regarding the creative process, Ranft once said, “It’s a challenge. The final product is the goal you’re searching for. [Your little sequence is] gonna get smashed, trashed. It’s gonna come apart for the good of the final film . . . it’s a paradox. You’ve got to put yourself into it, and then you’ve got to take yourself out of it. Be objective and not be hurt.”

And that’s the point of the two guys. They understood the value of the story and the center of the films they worked on and over. Nothing mattered, including personal insult, as long as the story came out right. They were film artists and knew how to get what they needed to complete their goals.

My personal preference is to want to know more about the old timer and to learn more about the golden age. However, it’s totally my bias, and the proof of this book’s success is that I was completely absorbed by all that was written about both men.

This is more than a good book. Anyone in love with animation should own a copy and read it carefully. There’s a lot there, and it’s all good. It’s stunningly designed with beautiful animation art treasures well displayed.

A telling board by Ranft.

________________

Amid Amidi offers an excellent interview with John Canemaker on the subjects of the book at his Cartoon Brew site. I recommend you all read it.

There’s also a video promo you can catch on YouTube if you’re more visually oriented.

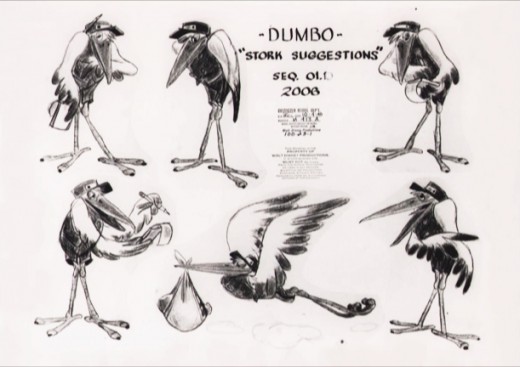

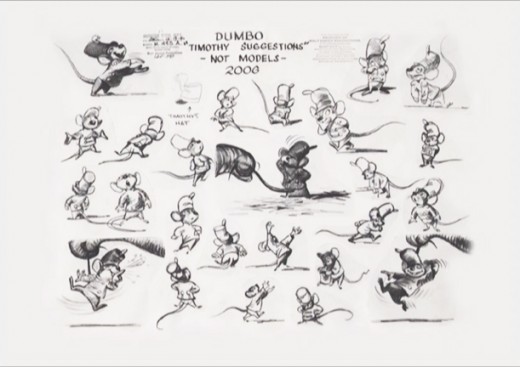

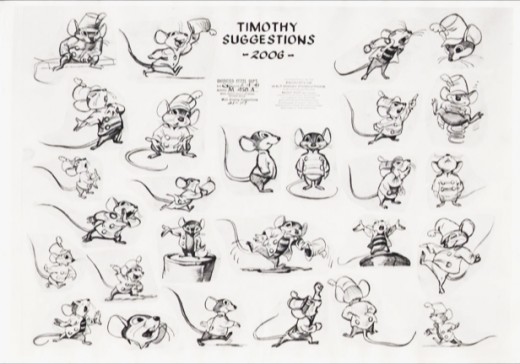

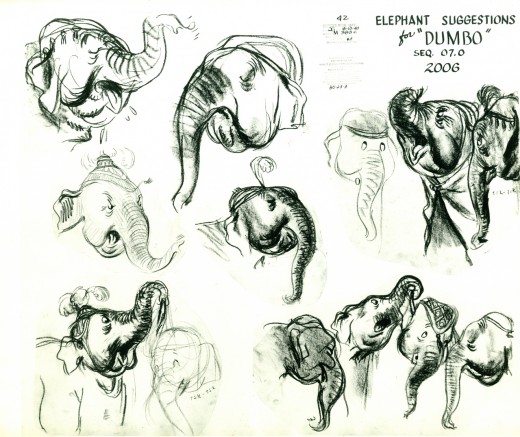

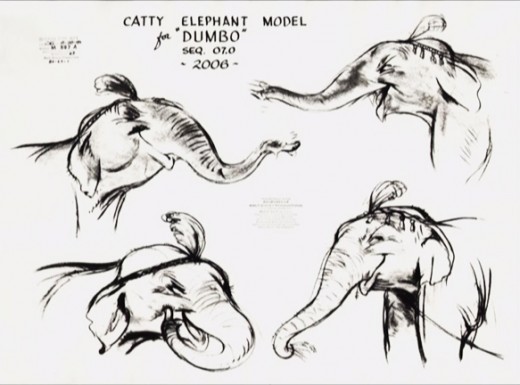

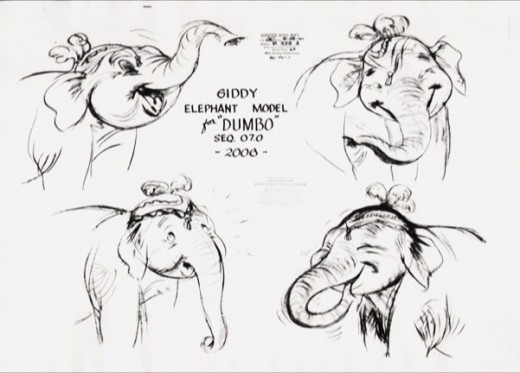

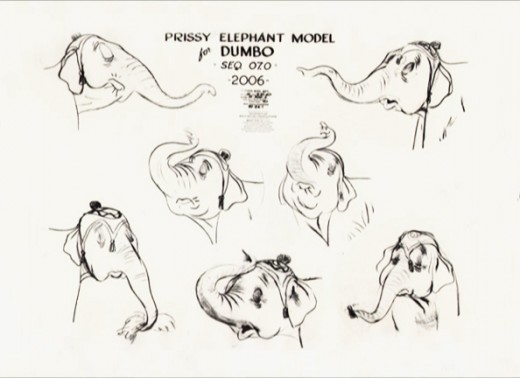

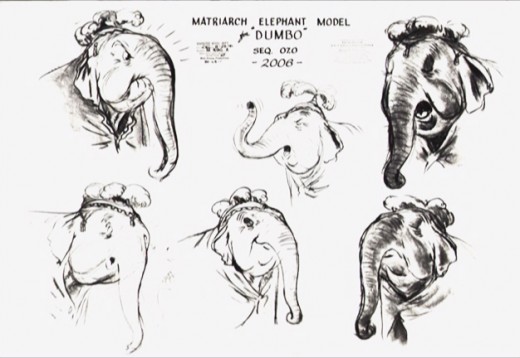

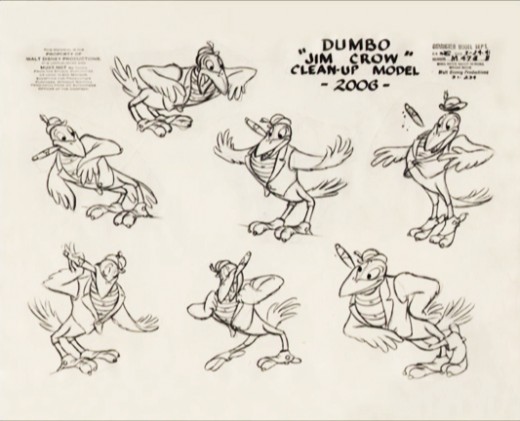

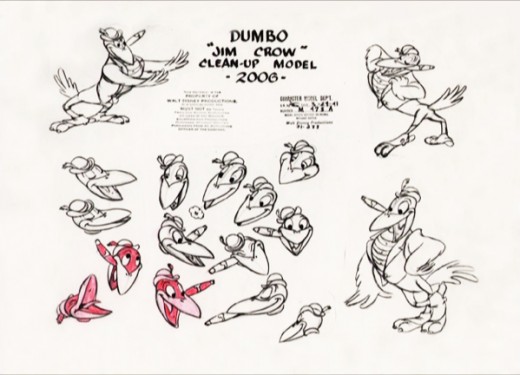

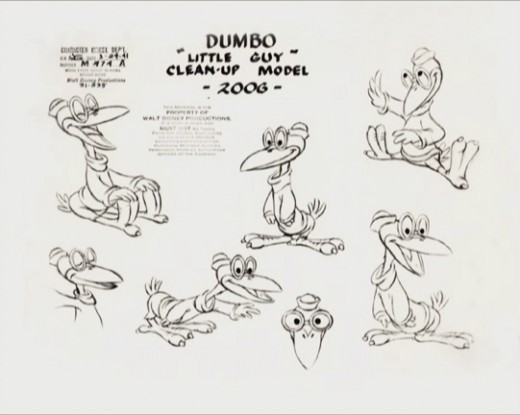

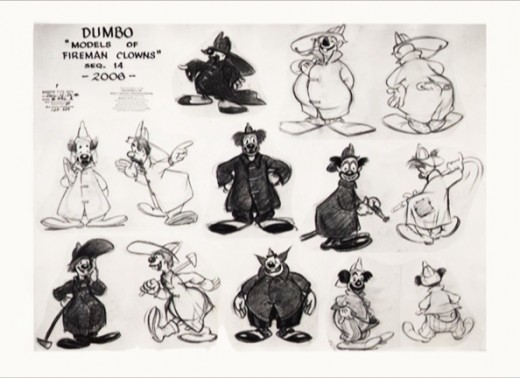

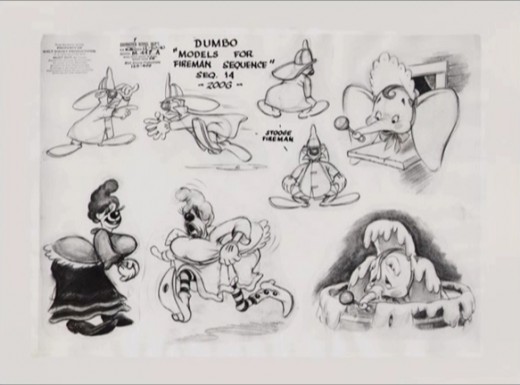

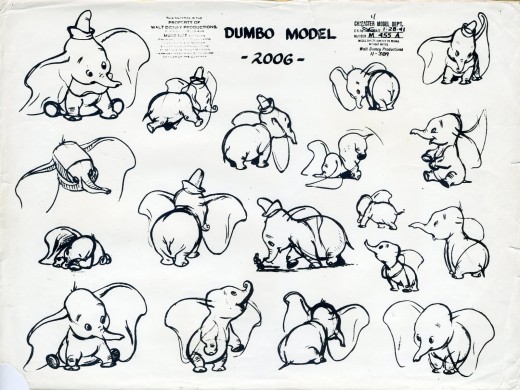

Animation Artifacts &Disney &Models 13 May 2010 07:50 am

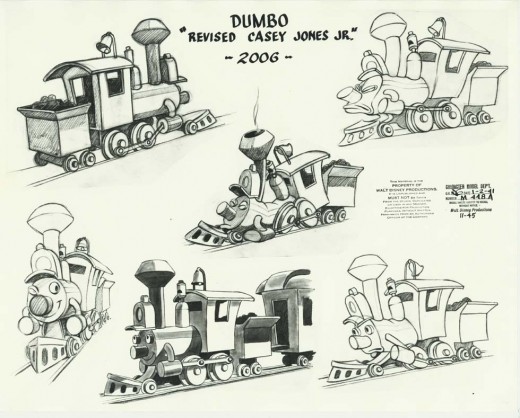

Dumbo Model Sheets

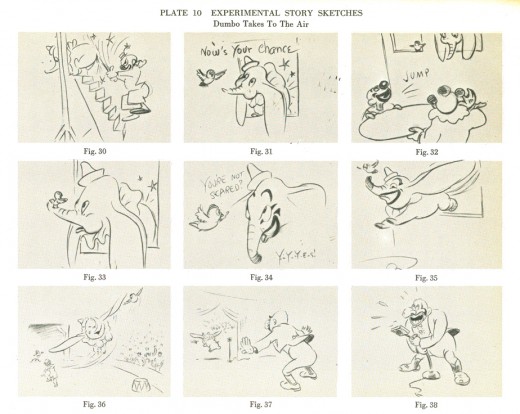

- I’ve made a concerted effort to locate as many of the Dumbo model sheets as I could. Some of these are scanned from the originals; others were lifted from an early version of the DVD for the film (and are consequently small images).

There are still more model sheets at Bob Cowan‘s wonderful site. Don’t hesitate to take a look.

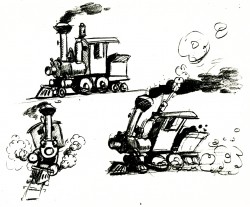

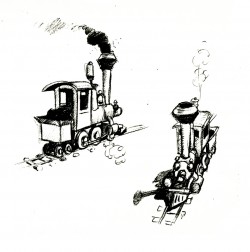

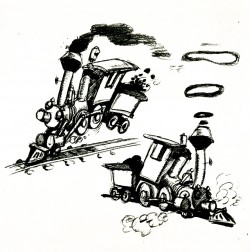

These are the first rough sketches done for Casey Jr. for both Dumbo and The Reluctant Dragon. Eventually, a headlight cap was added and the eye lamps were eliminated.

The eyes were drawn on the boiler’s front.

Robert Cowan sent me this model of Casey Jr. which was used in the final film.

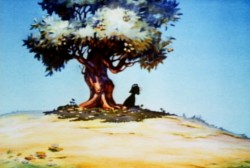

This final piece comes from the Robert Field book, The Art of Walt Disney, published in 1941. It’s a beautiful early storyboard for the climax to the flying sequence.

I’ve put this all together as part of an effort to join in the fun started by Hans Perk who has been posting the drafts for Dumbo, and this has led Mark Mayerson to start posting the brilliant Mosaics he creates for the film. Check out both of their sites.

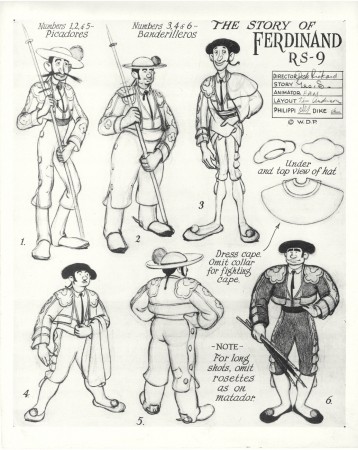

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 03 Mar 2010 09:05 am

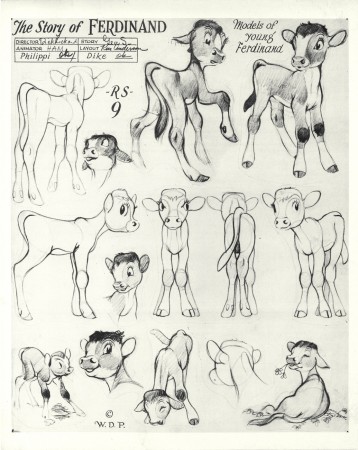

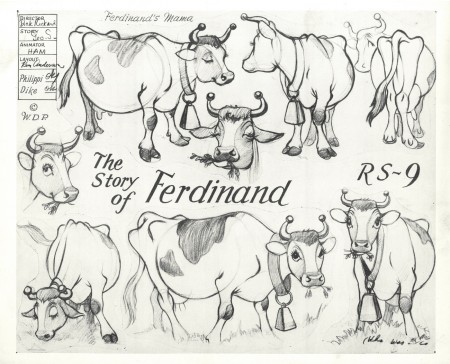

Ferdinand Models

– Ferdinand the Bull was a precious little animated short. It originally started out as a “Silly Symphony”, but then they called it a “Special” film. It was adapted from a classic children’s book by Munro Leaf which was illustrated by his longtime collaborator, Robert Lawson. The book, published in 1936, created a bit of a stir in Europe where the Spanish saw it as a call for pacifism when they were involved in a violent civil war and were getting entrenched in what would become World War II.

– Ferdinand the Bull was a precious little animated short. It originally started out as a “Silly Symphony”, but then they called it a “Special” film. It was adapted from a classic children’s book by Munro Leaf which was illustrated by his longtime collaborator, Robert Lawson. The book, published in 1936, created a bit of a stir in Europe where the Spanish saw it as a call for pacifism when they were involved in a violent civil war and were getting entrenched in what would become World War II.

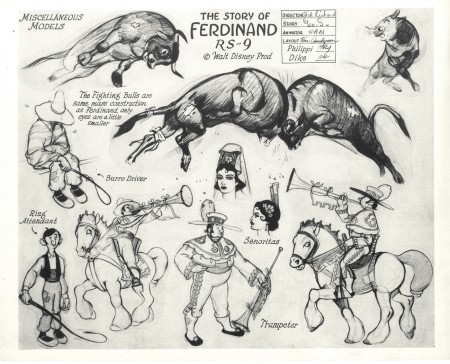

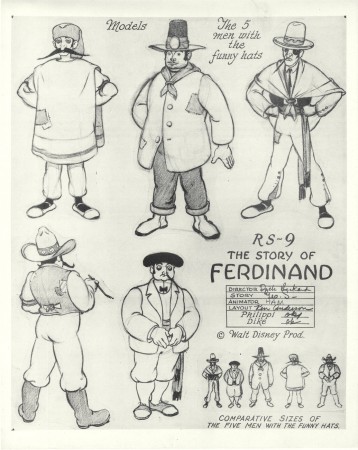

In making the film, the animators who worked on it seem to have had a lot of fun. Ward Kimball led the way by caricaturing others (see below) as the bullfighters who parade into the arena. You can get a glimpse of this in the model sheets from the film. Disney, himself, was drawn as the matador leading the charge. (At least Walt thought it was a caricature of him; Kimball said no.)

In their book, Too Funny for Words, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston wrote, “The parade of participants for the great bullfight in Ferdinand the Bull (1938) was a series of caricatures of animators and directors, with the animator who conceived the whole idea bringing up the rear and leering knowingly at the camera. It was rumored that Walt thought the matador was a caricature of himself, but the animator quickly denied giving the character any resemblance to his boss.”

The animator, Ward Kimball, took credit for caricaturing the cast, but said that the Matador was not Disney.

The short won the Oscar in 1938 as Best Animated Short.

Again, many thanks to Bill Peckmann for the loan of these models to post.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

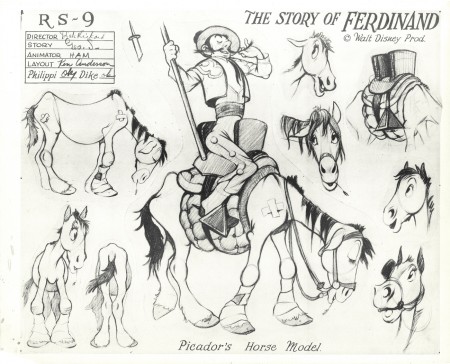

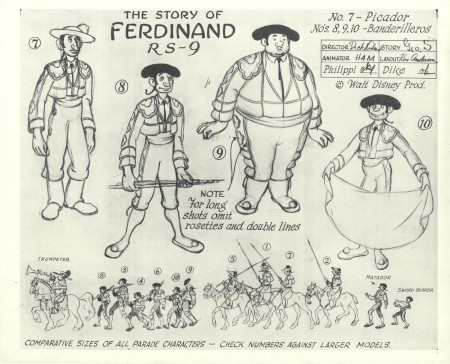

Picadors and Banderilleros (obviously before Kimball got to them.)

More Picadors and Banderilleros

I believe it’s Ham Luske leading, with Bill Tytla, Fred Moore and Art Babbitt following.

Michael Barrier corrected this (see comments) From left: Ham Luske, Jack Campbell, Fred Moore, and Art Babbitt

Jack Cambell leads these three, and I’m not sure of the others.

More from Mike Barrier’s comments: Tytla is the horseman at the middle. I believe the horseman to Tytla’s right is a caricature, too, but I can’t remember of whom.

Matador Walt Disney marches in front of Ward Kimball, bringing up the rear.

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 16 Feb 2010 09:40 am

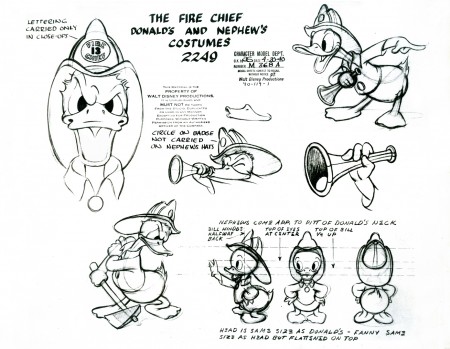

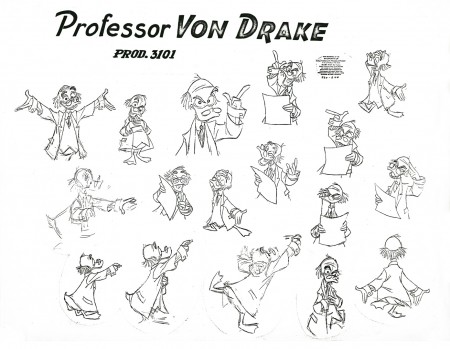

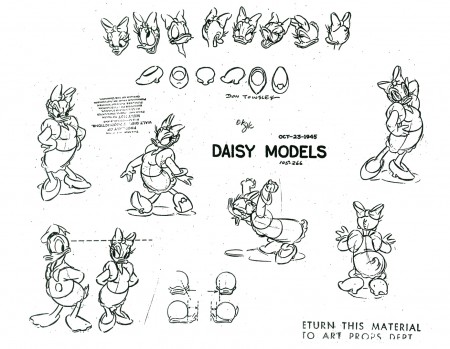

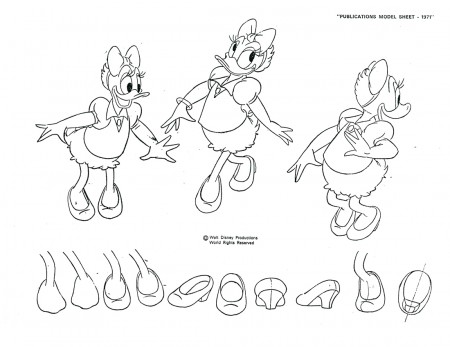

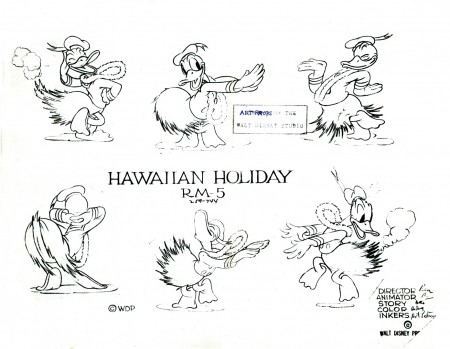

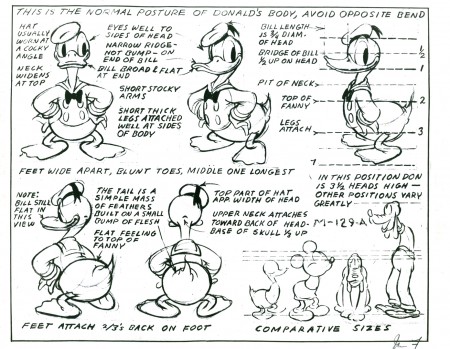

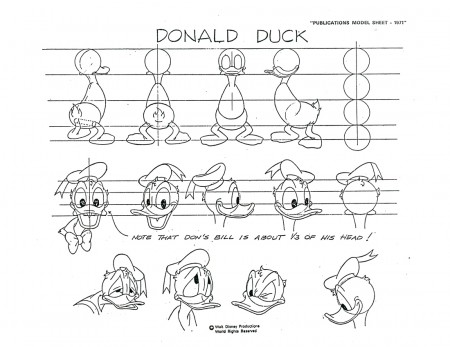

Donald Models – 2

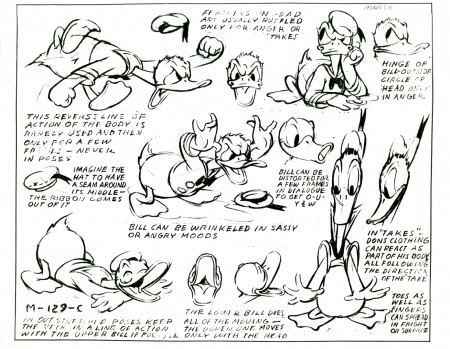

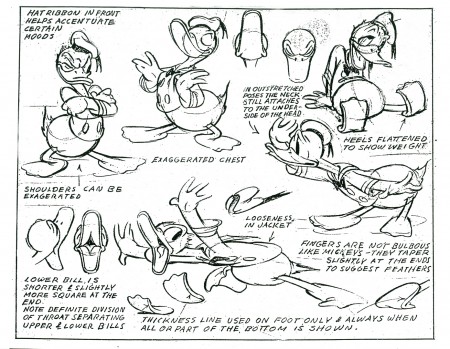

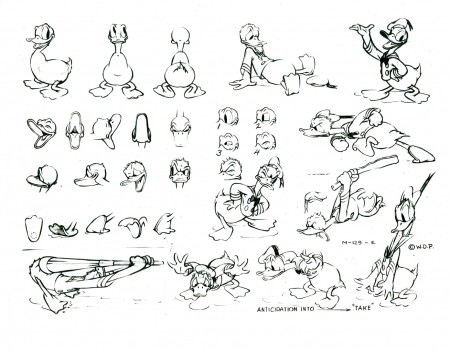

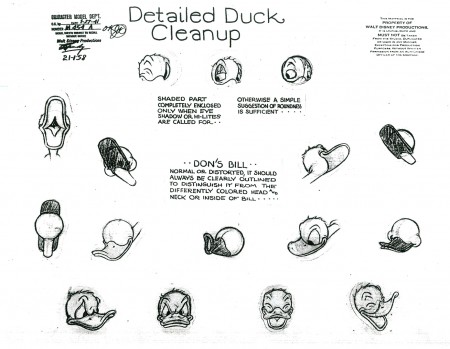

- Last week we had the Donald Models. Actually that was the second edition of Donald models, I’ve posted. The other was a while back – back in July 2009, there was the lecture notes written of the after-hours class held in the ’30s.

As I stated, last week, this post is dedicated to model sheets of Donald that are tied to specific films he was in. I love them all. They come from several periods of Disney shorts and Donalds. The first is from my favorite period for Donald, and I’m sorry he had to change from this guy; I love him. But I also love the Mickey of that period – 1931-32.

In the end we get into the TV Donald – but not too much.

Anyway, enough gab.

Love this character.

Hawaiian Holiday – Sept 24, 1937

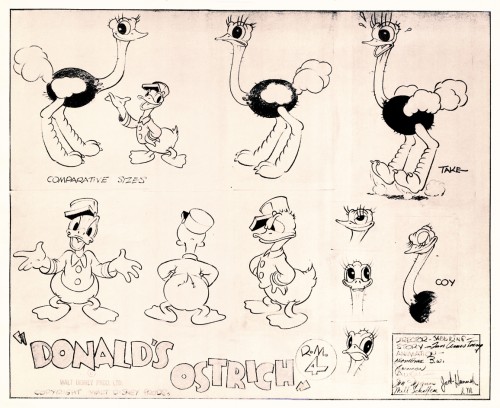

Donald’s Ostrich – Dec 10, 1937

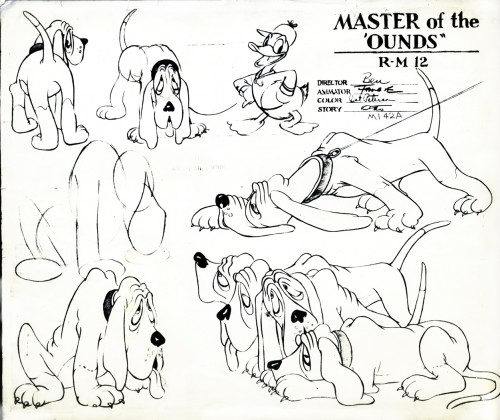

Master of the Hounds

retitled The Fox Hunt – July 29 1938

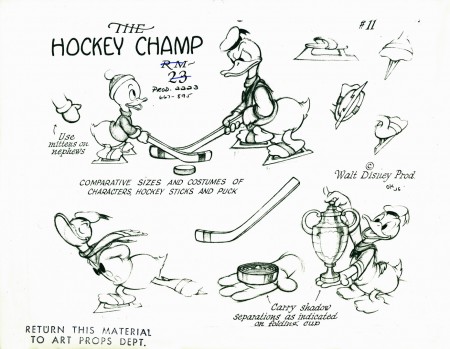

The Hockey Champ – Apr 28, 1939

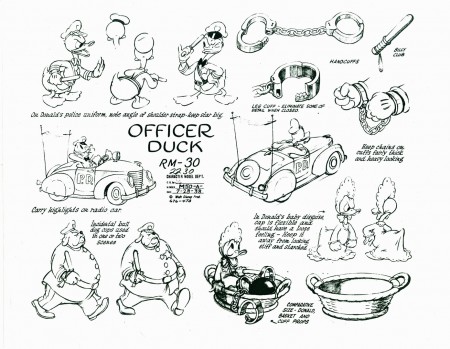

Officer Duck – October 10, 1939

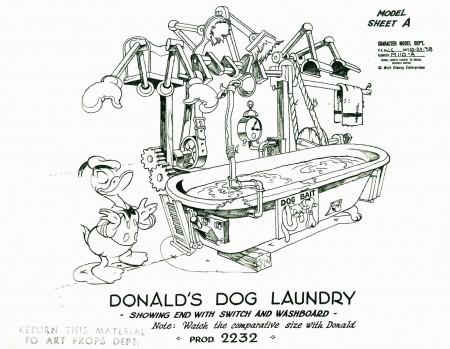

Donald’s Dog Laundry – April 5 1940

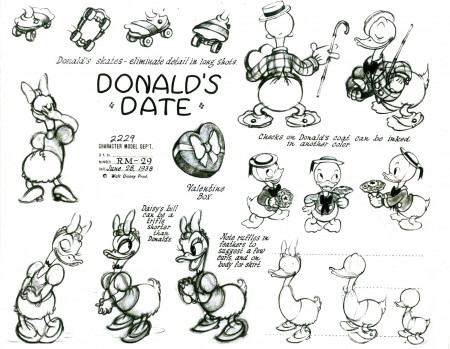

Donald’s Date

retitled Mr. Duck Steps Out – June 7 1940

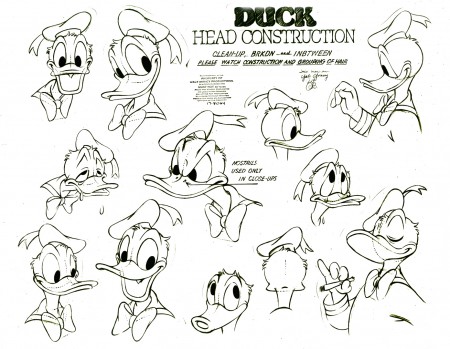

Just heads. This is getting to be late-period Donald.

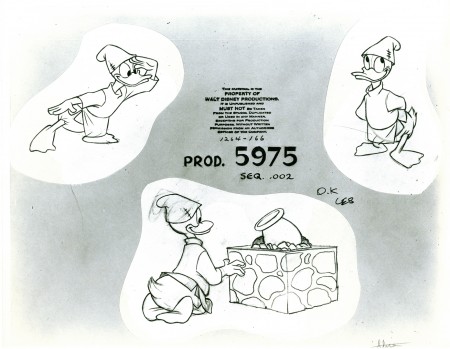

Here we have one from Steel and America (1964)

an Industrial done for the U.S.Steel Corporation.

Many thanks to the gracious Bill Peckmann for the loan of this material to post. His collection of model sheets is amazing.

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Disney &Models 08 Feb 2010 09:02 am

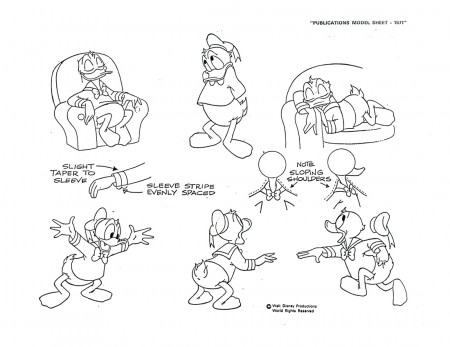

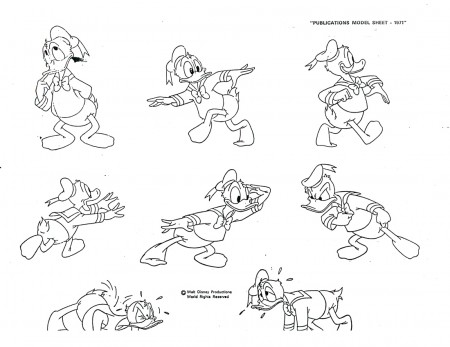

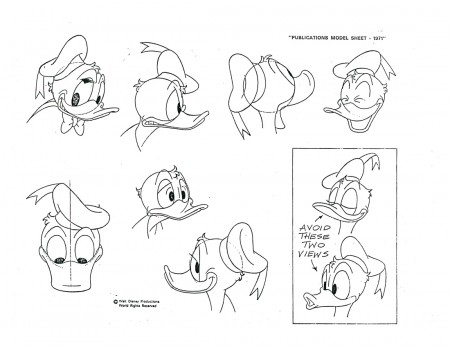

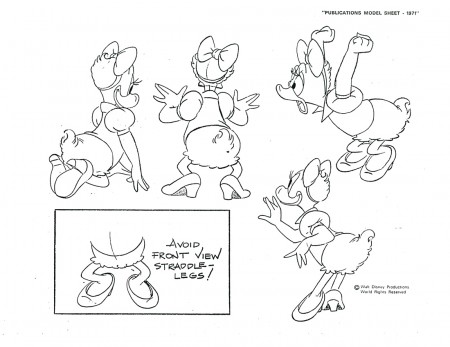

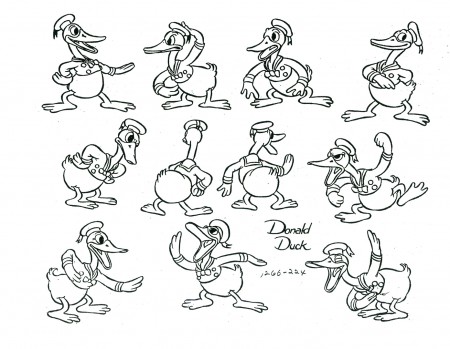

Donald Models

- I’ve spent a lot of time the past few Mondays posting models of Mickey Mouse. It’s only fair to move onto Donald Duck. Here are a lot of good models, mostly from the ’30s.

- I’ve spent a lot of time the past few Mondays posting models of Mickey Mouse. It’s only fair to move onto Donald Duck. Here are a lot of good models, mostly from the ’30s.

I follow this first group with some really clean models designed for publishing. I think you’ll see how heartfelt the first batch are compared to the second group done in the ’50s.

You can also see an earlier post I did of the Disney lecture on Donald and how to draw him.

1

1

The following are designed for publishing, not animation:

1

1

Next week I’ll follow with a number of models from specific films, all of which are gems.

I have to thank the inestimable courtesy of Bill Peckmann for the loan of these sheets. I am deeply grateful.

Animation Artifacts &Bill Peckmann &Models 31 Dec 2009 08:49 am

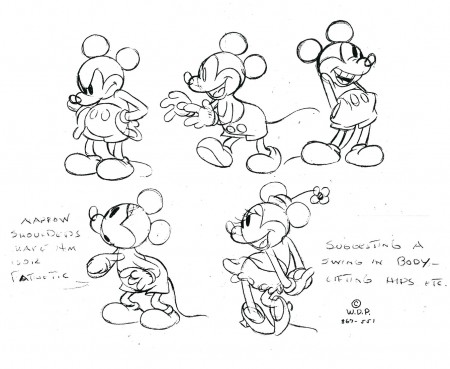

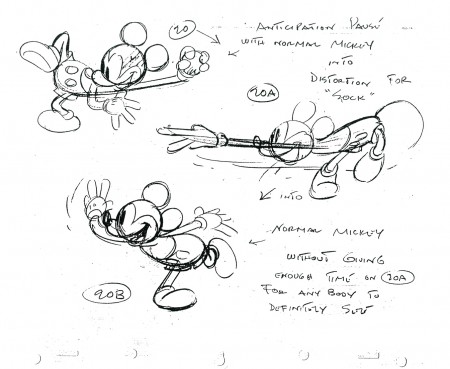

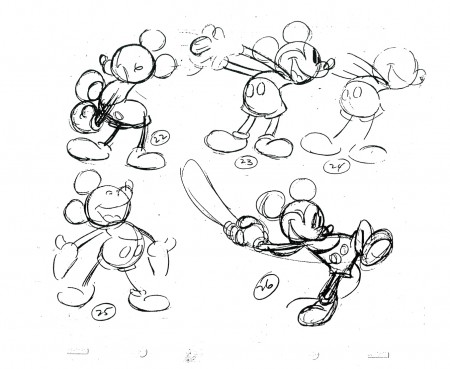

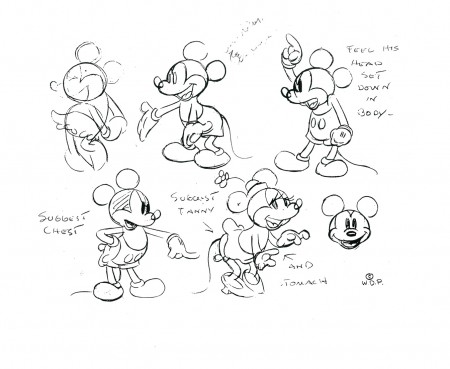

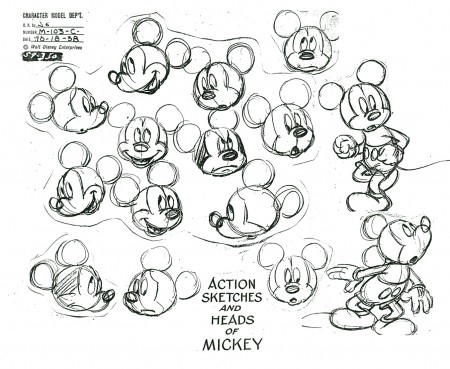

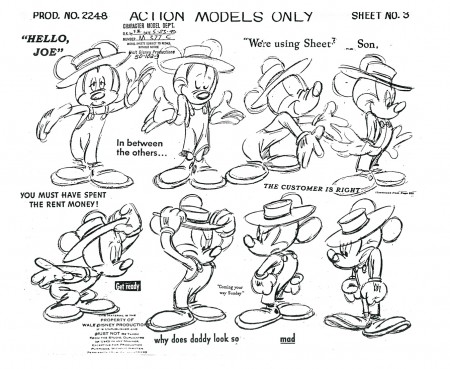

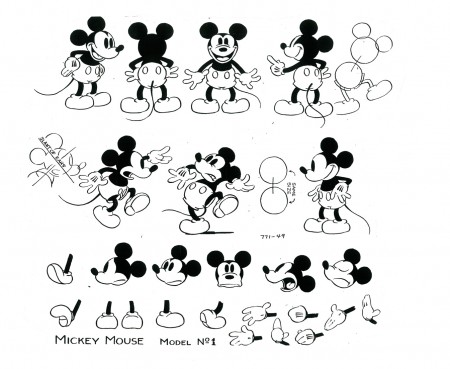

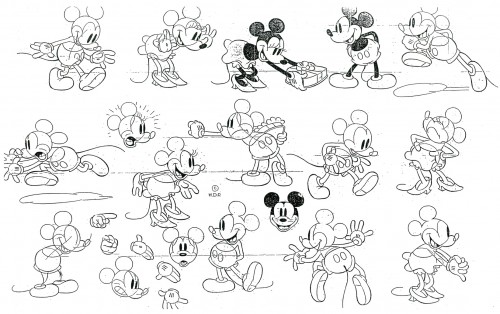

More Mickey Models

- Bill Peckmann has generously loaned me another very large stash of character model sheets, primarily Disney. There’s a wealth of Mickeys, alone.

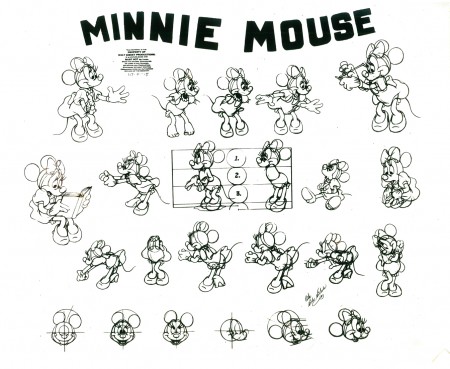

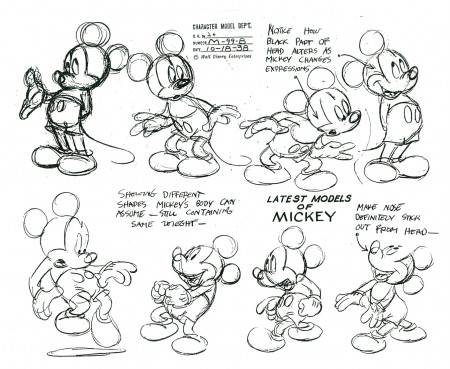

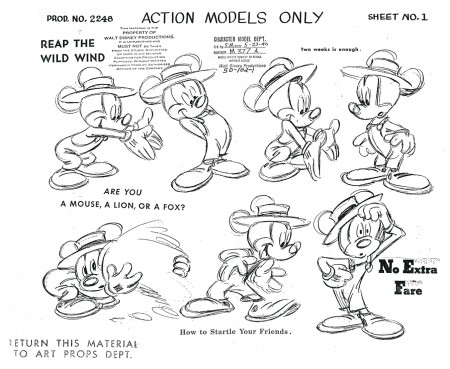

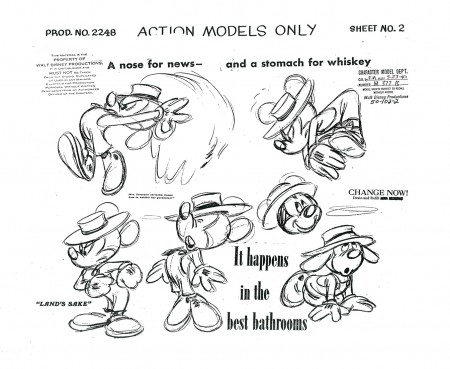

I’ve posted some of them before, many in much poorer condition. Consequently, I’m about to spend some time with Mickey and Minnie, and post some new, some old and some out of this world models of the pair.

Here’s a large number of them. I’m holding back some animation charts from L’il Whirlwind and The Symphony Hour which will come at a later date.

Let’s start with a nice early Mickey.

Then a Minnie and Mickey together.

Here’s a beautiful Minnie model.

1

1

These are the models from the Disney lecture posted here.

1

1

These next four are the model sheets drawn by Ward Kimball.

2

2

The earlier versions of these Kimball models that I published were

in horrible condition. It’s nice to post such clean versions of them.

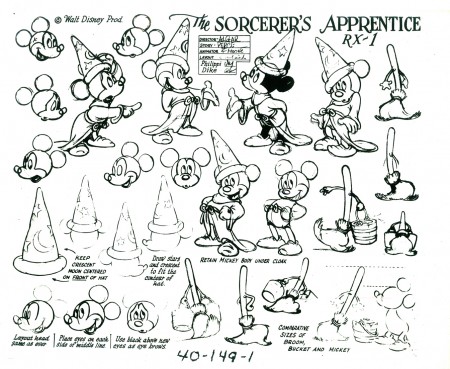

Here’s a fine copy of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice model sheet.

1

1

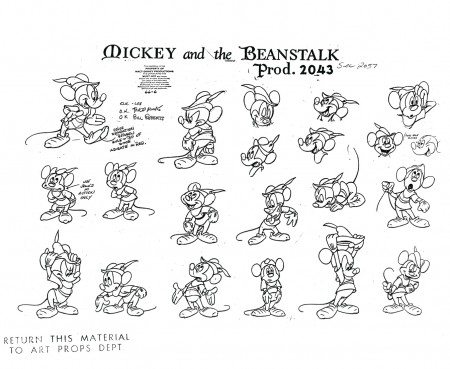

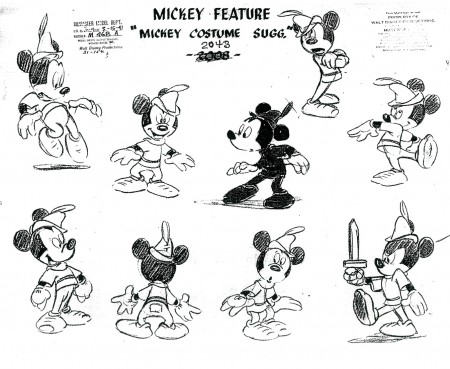

These two model sheets from Mickey and the Beanstalk are new to me.

1

1

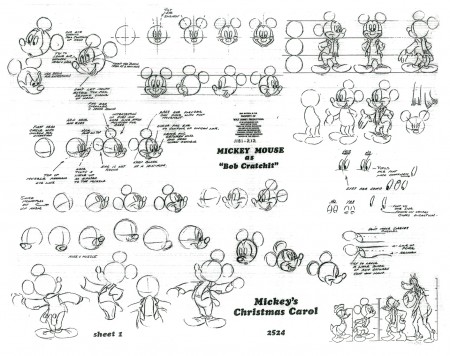

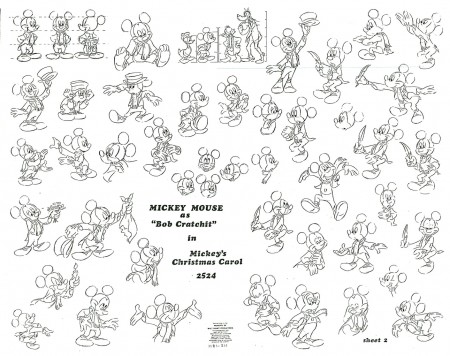

And, finally, these two charts from Mickey’s last

hand-drawn short, Mickey’s Christmas Carol.

2

2

Now Mickey’s a cgi character and completely off-model (and unwatchable.)

Thankyou, yet again, to Bill Peckmann for sharing these with us.

.

There are three interesting model sheets at David Lesjak’s excellent site Vintage Disney Collectibles.