The following is from the book, Storytelling in Animation, The Art of the Animated Image Vol 2. This is an anthology that was edited by John Canemaker which was published in conjunction with the Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

Walter Lantz Conference – 1988

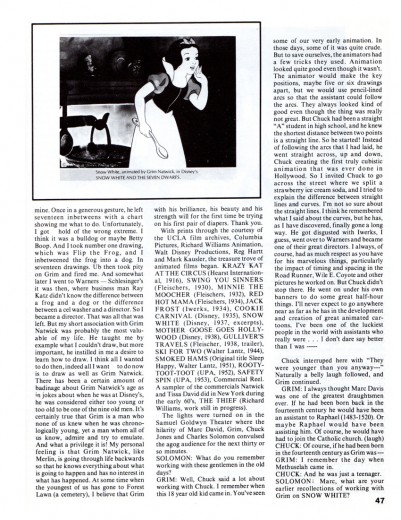

A Conversation with Caroline Leaf

This transcript has been abridged from the “Tribute to Caroline Leaf” that took place on June 11,1988 during The Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

JOHN CANEMAKER: When Caroline Leaf was beginning work on her masterful short film THE STREET, she told an interviewer, “I wanted to tell stories with my films, and I used animal legends and myths. Now I am working more on dramatic representation: dialogue, character and human problems. Perhaps dramatic expression is not ultimately the best form for animation, but still, I do not try to do what live-action can do better. The strongest influence on me is from literature rather than film. Kafka, Genet, lonesco, Beckett, have affected me most with the depths of their visions and world views and ways of breaking up time to tell a story.”

Caroline Leaf’s work is a wonderful synthesis of many of the storytelling techniques and animation methods discussed at this conference. She represents to me both the old and the new—the traditional and the experimental. Her use of direct, under the camera techniques and brilliant metamorphoses recall the pioneering works of James Stuart Blackton and Emile Cohl. Her perfect sense of timing and implementation of personality to individuate her characters echoes the balletic movements and emotional impact of the best of Disney. Within her films the imagery can be, at one moment, representational, and, in the transitions, non-objective abstraction. Caroline tells ancient folk tales as well as modern short stories. And she uses tools as primal as her hands to position paint on a smooth surface, or push sand grains into impressionistic symbols. She records her art with a modern invention, the movie camera, which allows her to bring inert designs and stories to life, a miracle never realized by artists until our century.

Caroline Leaf created her finest films at the National Film Board of Canada, a sympathetic but nonetheless corporate structure, in which she has managed to retain her individuality and personal signature. She is also a vital link in the list of women animators, designers and storytellers past and present who have made their way in a male-dominated field. From the simplest means she conjures a complex world of emotions, which is a talent found only in the work of the greatest artists. The transformation and alienation of a man turned into a loathsome cockroach; the variety of feelings triggered in family members by the imminent death of a loved one; the pathetic, ultimately self-destructive attempts of a lovesick owl to assimilate into a different culture; a small boy and assorted animals facing death in the form of an eerily omniscient wolf are some of the stories told with consummate skill in the films of Caroline Leaf. I’m so glad you’re here.

CAROLINE LEAF: I’m glad to be here.

CANEMAKER: I think that what’s extraordinary about seeing all your work together like this is to view your first film and to realize that it was all there—right at the very beginning. The good design, the sense of timing, and your whole bold approach to the medium is already there—your ideas about how to tell the story. That was your first film, wasn’t it?

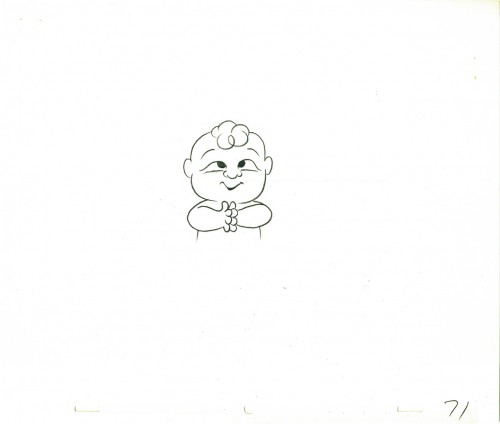

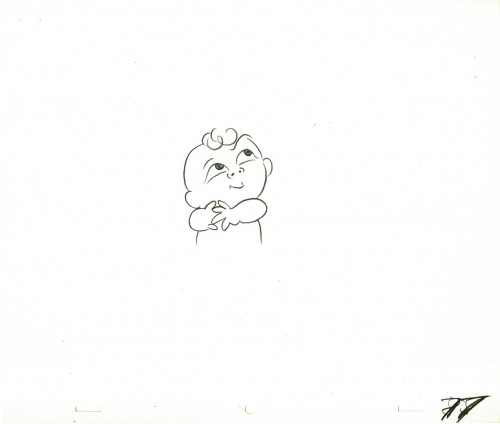

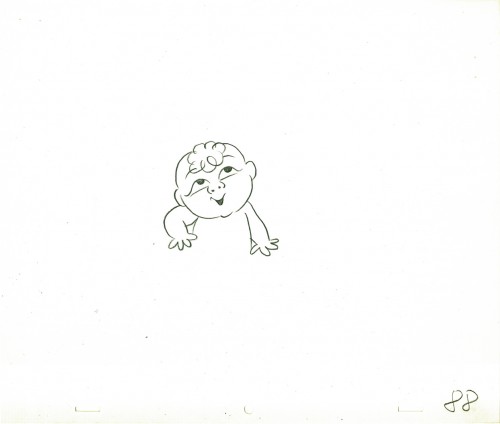

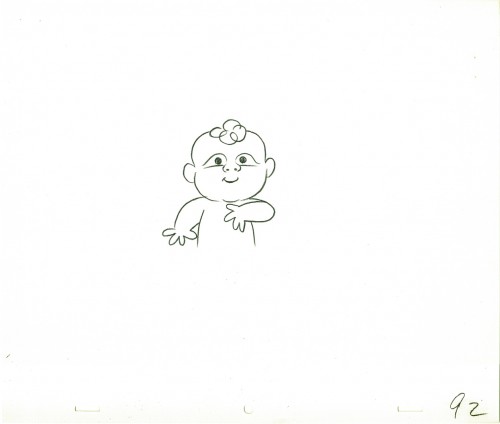

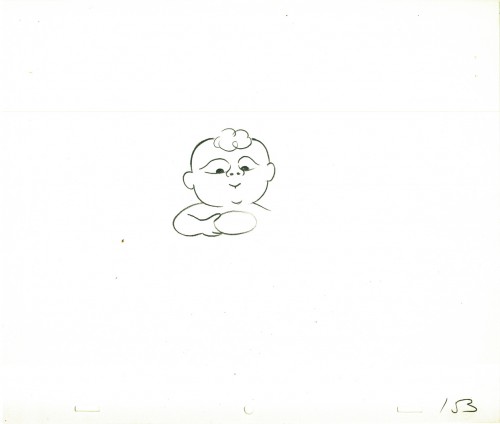

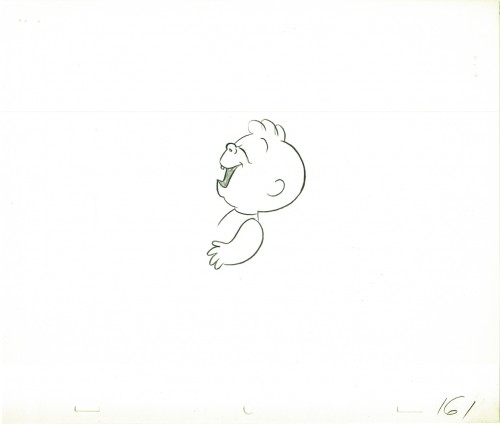

LEAF: PETER AND THE WOLF (1969) is my first film. And I must say, I agree. I haven’t changed very much.

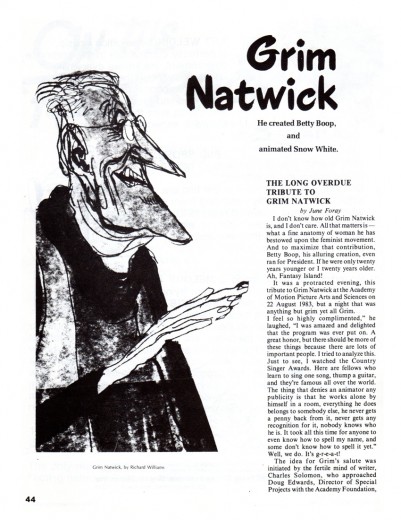

CANEMAKER: Grim Natwick always said that timing is the last thing an animator learns. It seems as if it was the first thing that you learned. Where did that come from? Were you trained in theatrics in any way?

LEAF: I’m not sure where it comes from. I think I make shapes and then try to keep them in balance. That’s my idea of how they move. I don’t know how to say where the timing comes from.

CANEMAKER: But you also know when to not make them move—you have a good sense about “holds.” When the cockroach was looking in the mirror, it went on and on, and you had the guts to keep it there without having it move at all.

LEAF: I’ve heard people talk about feeling the movement, and I know that I feel it. Sometimes I have to get up and act something out, or look in the mirror to see what it looks like when something happens. Working directly under the camera the way I do, there’s nothing between me and drawing the motion, and that helps with that. Intuitive expression of the movement, the timing. CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about story. In PETER AND THE WOLF, it’s very experimental. In many ways it is a first film because you get a feeling you’re trying to do a lot of different things. How did you approach the story in PETER AND THE WOLF? There’s just barely a theme of Prokofiev in the beginning —it’s all there, yet it isn’t.

LEAF: I’ve read a lot, and I’ve been most influenced by stories that I have some good gut feeling about. But then I like to go off and do my own thing with them. And on that film in particular—you’re right, I was trying to experiment; and the way I was working, I just had to divide things into segments. The ideas would evolve out of a little pile of sand and then go into wh’ite, and then a few days later I’d start a new sequence. So, it was pretty much the situation of wanting to use a story while not following it precisely.

CANEMAKER: And you use touches of personality, too: the little goose steps down but has a very particular way of doing it and it got a couple of laughs each time because it was so goose-like. Your characters have a lot of personality. Do you feel that personality guides story?

LEAF: Can they be equal?

CANEMAKER: Whatever you want! Anything you want, Caroline!

LEAF: I would say the story is important to me because it sets the limits and anything I do I don’t want to deviate from the feeling I want to generate from the story. The characters are the vehicles that express the stories, so they have to be right for each other. And I don’t indulge the characters, I don’t think, because I would get off track with my story, so I think I always sustain a line to keep the story moving along.

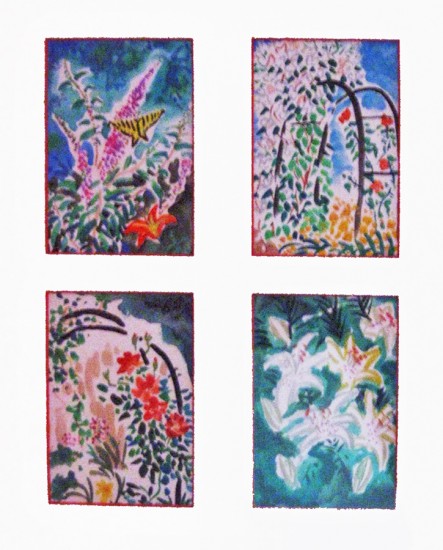

THE STREET (1976), adapted from Mordecai Richler’s story

CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about THE STREET (1976). How detailed was the original short story? Why did you approach it?

LEAF: I just liked the story, but there I had Mordecai Richler, a living person, a writer who lived not too far away from me, and I wanted to respect his writing. His story was maybe twenty pages, and at first I thought that to be respectful to the writer I should put everything onto film. And I found as I was working, the more I could pare away the words and just work with the imagery and be true to the feeling I was getting in the story, the better it worked on film. So there I was really trying to follow his story, but because film is a different medium, it came out in a different form.

CANEMAKER: Did you ever show it to him or did you confer with him during the making of it at all?

LEAF: No, he was strangely disinterested. He didn’t like the story too much, and didn’t care what I did with it, and never got in contact with me about it. I didn’t discuss it with him.

CANEMAKER: Did he ever see the finished film?

LEAF: I sent him a print and he never answered. I don’t know what he thinks of it.

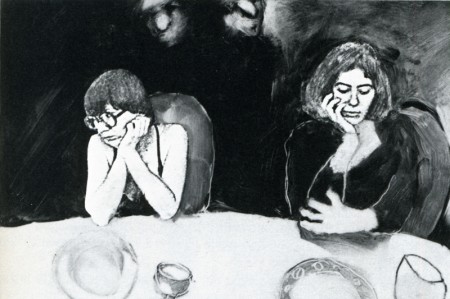

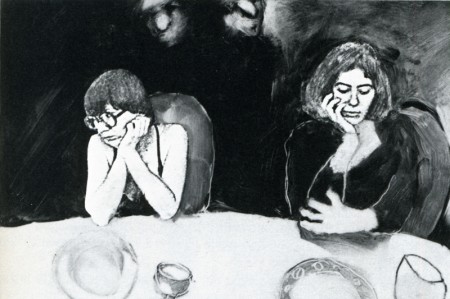

A family beset in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)

CANEMAKER: What about Kafka? Was your approach to pare away and get the imagery first in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)?

LEAF: The Kafka story is so complicated and wonderful. There I took just the element of what I was thinking about most—how horrible it would be to have a body, or the external part of one’s self that’s seen by the world be different from what’s inside one’s self, and not be able to communicate that. Since I’m a storyteller, I just worked with that one aspect of Kafka, so it’s quite different from his original story.

CANEMAKER: You really get into your characters; the emotion is there, it’s really extraordinary, I think. It’s just great. (Audience applauds.) Caroline doesn’t like to be interviewed, but she’s consented to this, and I appreciate it. I’d like to talk about the animated projects you’re working on now. One of them is a scratch-on-film technique.

LEAF: I’m just in the midst of starting two projects, and because I’ve been involved with live-action filming for a few years, and writing for live-action, now I’ve got a story that has all the characteristics and psychology and emotion of a live-action film, but I’m doing the images scratching on film. It is quite a restricted and crude image that I can make, but I find it exciting to find what I can tell of the story in imagery and how much I’ll have to rely on words.

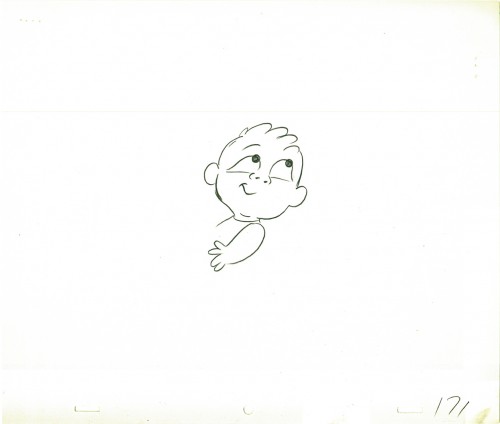

Autobiographical insight in INTERVIEW (1979), co-directed with Veronica Soul

And the other project is a test of a computer animation program. It’s a small project, a program called Pastel, that was developed by the Film Board. They wanted to see how an animator would work with it, and what modifications it still needs.

CANEMAKER: Exciting. So you haven’t abandoned animation.

LEAF: No. Not at all. I just have had a hard time sitting still and doing it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I noticed in INTERVIEW (1979) that you had all those little thumbnails to the left [of the work under the camera]. Is that how you work, really planning it out in little sketches like that?

LEAF: Yes, that would be my detailed storyboard as I go along. I don’t storyboard too closely; to have done all the fun work, and to animate it, there are no surprises left. But I also need to know where I’m going since I work under the camera. If I take a wrong turn I can’fgo back. So, as I come to each scene, I do some little sketches, particularly to know what the characters look like in different positions, so I don’t get lost.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Your soundtracks have a powerful impact on the film. How much do you get involved? Do you sound-mix, or do you direct the actors and the dialogue?

LEAF: I am very involved with my soundtracks, and I enjoy working on them very much. The soundtrack for THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974) was the first one I really conceived and executed. But when I’m working at the Film Board, I’m not the mixer, and I’m not the recorder, usually. There’s a crew of people that do that for me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You’re able to tell a story mostly through images, yet in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA and THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE you alter the language. Why did you make those choices?

LEAF: The Kafka story wasn’t in the public domain and I didn’t have the rights to the translation, so I made up a kind of gobbledy-gook language for that. And the Eskimo film was not a language you understood, either. They were speaking the Eskimo language.

CANEMAKER: THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE is exquisite. Sometimes in animation there are images you want to continue on and on and on. That scene of the birds flying, and the sound of wings getting as big and close as they are, and then they’re flapping for a while in front of you. I could watch it for a long time.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In that vein, I’d like to know how long you studied the animals to get their movements so perfect.

LEAF: I don’t study animals. I don’t go to the zoo. And in fact my movement isn’t very realistic. I think you can make it convincing. It fits the shapes, I think. I’ve never really looked to see how birds fly, and it’s kind of awkward in fact how they do, but it somehow works.

CANEMAKER: In several films you have a character who will take a step and then the legs would switch in some unnatural way—but somehow it works. In THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE I think there’s a section where that happens.

LEAF: I know it happens in THE STREET once — arms change . . .

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Why are you working in Canada? Economics?

LEAF: Yes, the Film Board is quite a special place. It’s allowed me to do the films that I’ve done, which I don’t think I could have done down here.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Because no one’s going to buy them? Or distribute them?

LEAF: It’s because of the problem with the distribution of short films. Ask any of the independent animators who’ve spoken here. Most of them are teaching, and it’s hard to have films seen. I found it is also hard at the Film Board. It’s difficult to have short films seen, and I’m not happy with the distribution, but I’m paid a salary there, and I’m quite free. Not totally free, because it’s a government film agency, and there are restrictions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What kind of restrictions?

LEAF: I find there’s a rather insidious way of thinking that grows on one working in a place like that. The most obvious thing is that it’s not possible to experiment; or it’s not easy to do an abstract film, because they’re always concerned about their market, which is an educational market. And besides that they’re very sensitive to not provoke any public outrage, or outcry, so they take a middle road. Nothing should be too controversial. I can read stories and know right away, this is something that could be done at the Film Board or not. One isn’t free to do exactly what one would like to do but one can mold it to be close enough to be satisfying.

Exquisite images of geese in flight in THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Does the Film Board expect to make their money back on films?

LEAF: No. The income they receive from the films goes back into production, but the Board receives government money each year. They have an annual amount given to them from Parliament. It’s voted each year.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Has it been growing?

LEAF: It’s been shrinking in recent years. So the place has shrunk a lot. Just last year they were voted an increase, which might just bring them equal with inflation for the first time in a few years. But everyone takes it as a vote of confidence.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Who owns the films you made while you were on salary?

LEAF: The Film Board owns them. I don’t have any rights to them at all.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do you think that your technique would be used in any major projects, for instance in a Disney feature?

LEAF: Well, I’ve seen my way of transforming used in eel animation. But actually the way I work, under the camera, I don’t think I can work as a team in that way. So it would be hard to make a long film using my technique, and get everyone working in a way that looks the same, This winter I did a commercial in New York, arid that was the first time I’d really found that my under the camera technique could work commercially. Because normally I would do some designs and then I would start, and I’d go to the end. And here I didn’t have any way to fit into the system of checks and balances that are used commercially. The client couldn’t see beforehand what I was going to do. But I evolved enough different systems of storyboarding that they felt reasonably secure, when I started animating, what they’d get when I’d

finished.

CANEMAKER: If it were possible to direct other people in your technique, would you be interested in doing a feature?

LEAF: No, I wouldn’t. I can’t imagine directing other people, and also I have a lot of fun when my fingers are doing it and I discover for myself little things. That’s what keeps me going. And I don’t know what it would be like, if it would be enjoyable to direct other people.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you ever used colored sand?

LEAF: I got tangled in knots one time trying to use colored sand. When you use colored sand—colored anything—you put a lot of time into keeping your colors separate, so they don’t all become like mud. And keeping colored sand grains separate was very difficult! I gave it up quickly.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you had students or apprentices pick up on your technique and pursue it in their own pictures?

LEAF: There are a few people that have worked in the same materials that I’ve worked in, but not as many as I’d like. And I haven’t had students. I haven’t taught.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Will you be working on a team for the computer animation?

LEAF: This is just a small project, and I’m alone with the guy that developed the program. We’re working together. He listens to my complaints and makes alterations. I’m amazed sometimes by what he’s done, but it’s not really a team.

CANEMAKER: I would like to thank Caroline Leaf for being here.

LEAF: Thank you for being here!

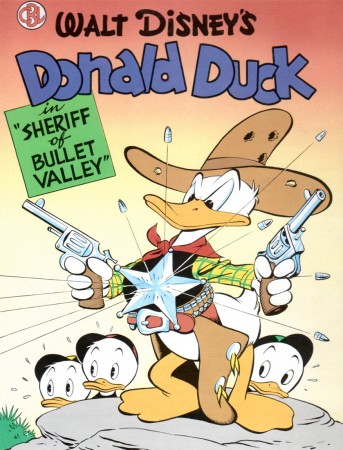

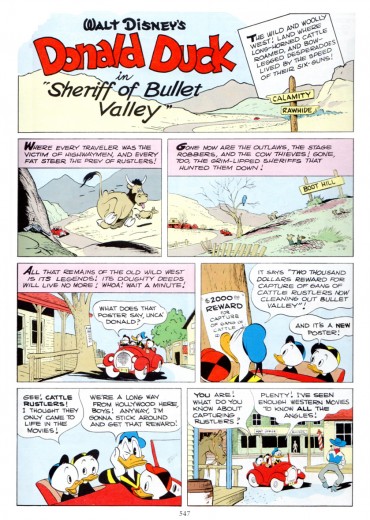

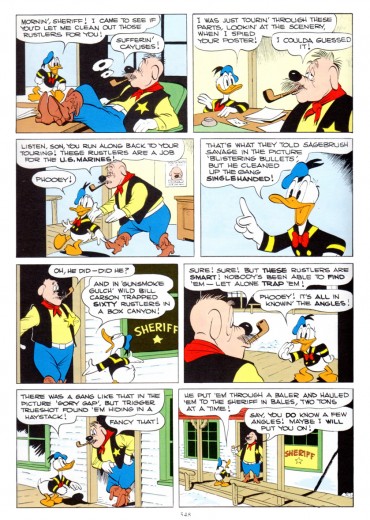

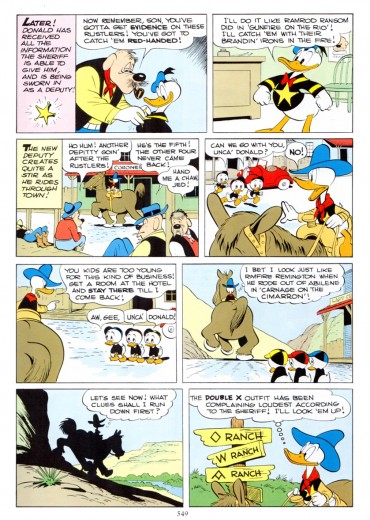

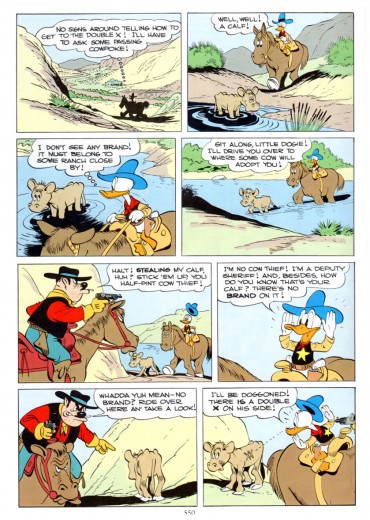

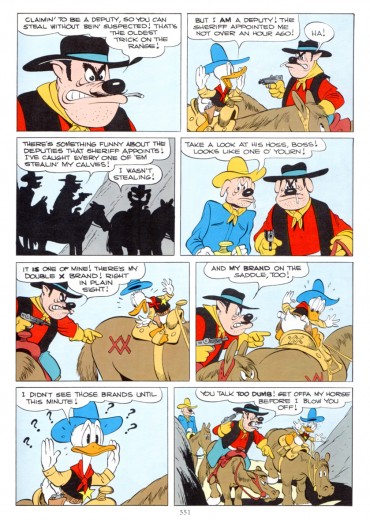

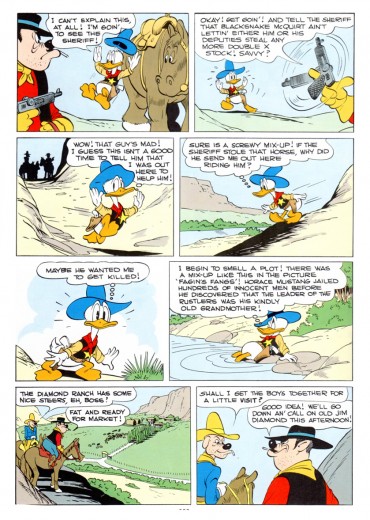

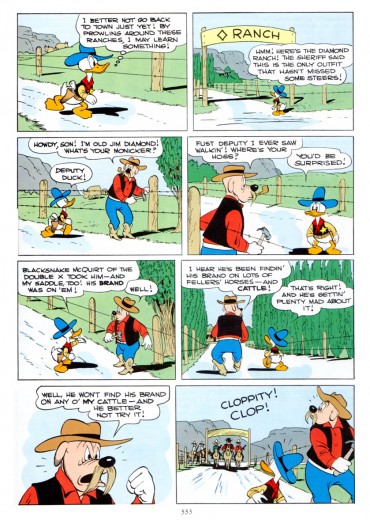

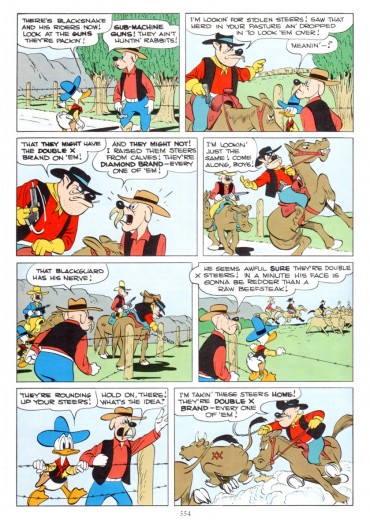

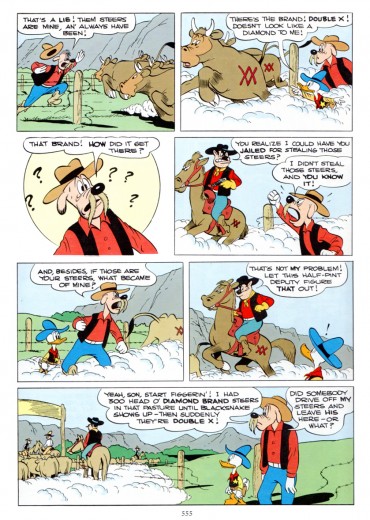

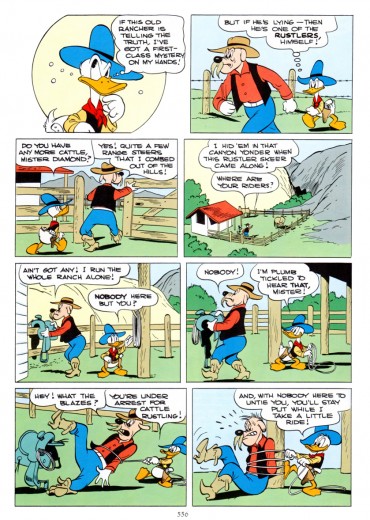

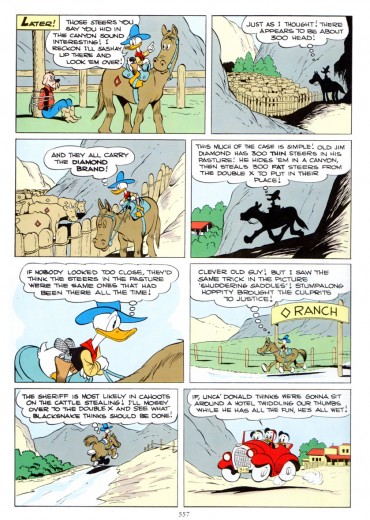

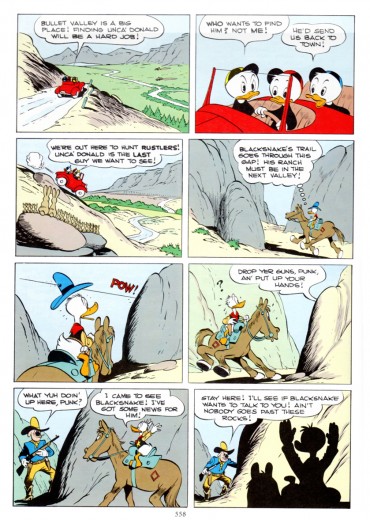

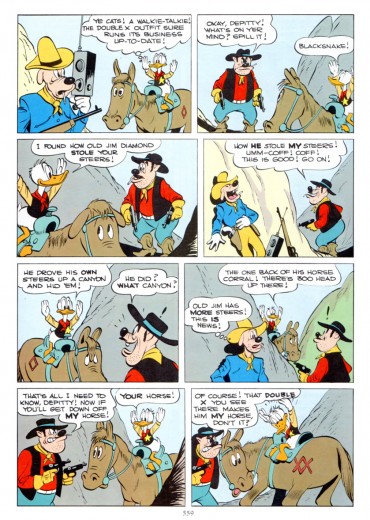

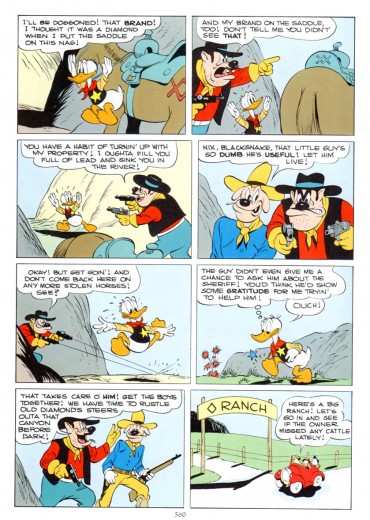

“Sheriff of Bullet Valley” was reprinted in Another Rainbow Pubishing Company’s “Carl Barks Library” in 1984. Most of the “CBL” was printed in B&W, fortunately “Sheriff” was printed in color and what a beautiful job they did. The coloring is done in wonderful flat tones, no color gradients and that seems to be just what the doctor ordered for Carl’s style.

“Sheriff of Bullet Valley” was reprinted in Another Rainbow Pubishing Company’s “Carl Barks Library” in 1984. Most of the “CBL” was printed in B&W, fortunately “Sheriff” was printed in color and what a beautiful job they did. The coloring is done in wonderful flat tones, no color gradients and that seems to be just what the doctor ordered for Carl’s style.

1

1

7

7

1

1