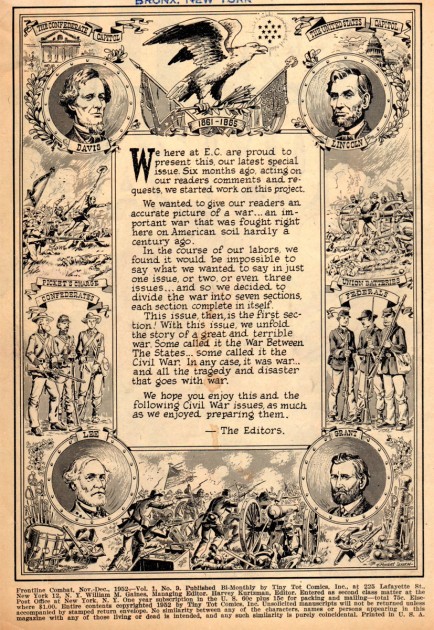

Independent Animation 15 Nov 2011 06:55 am

Lisa Crafts – Independent Animator

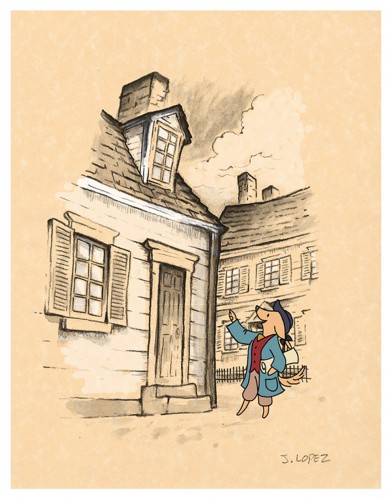

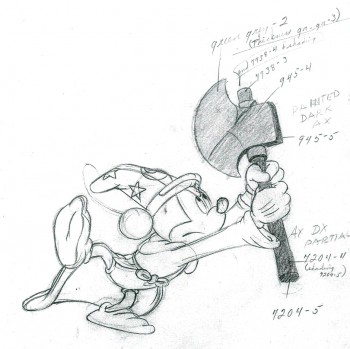

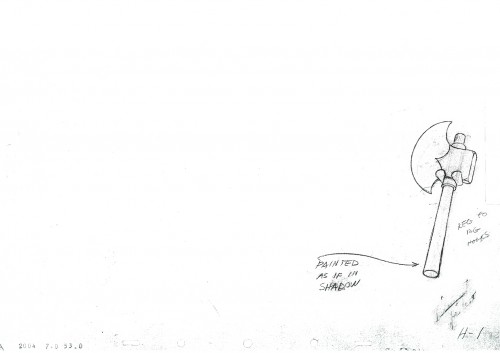

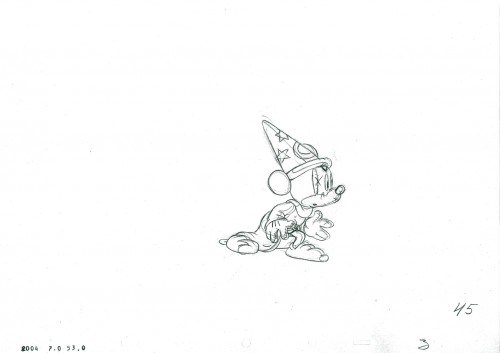

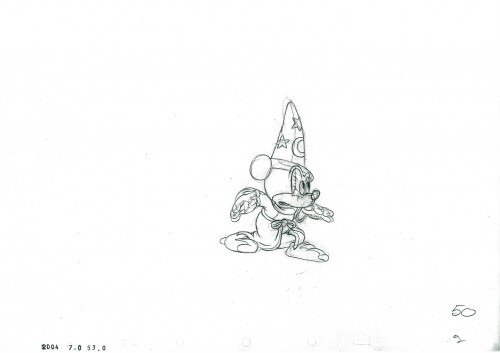

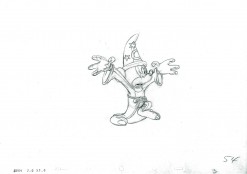

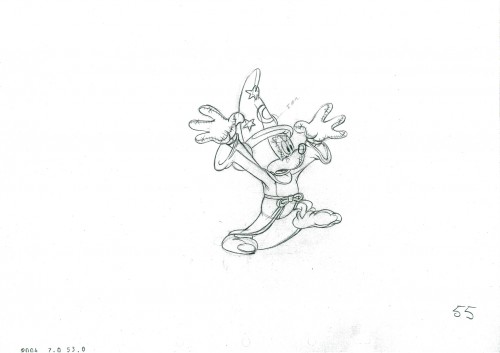

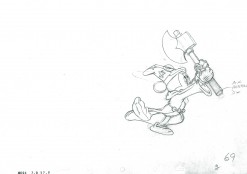

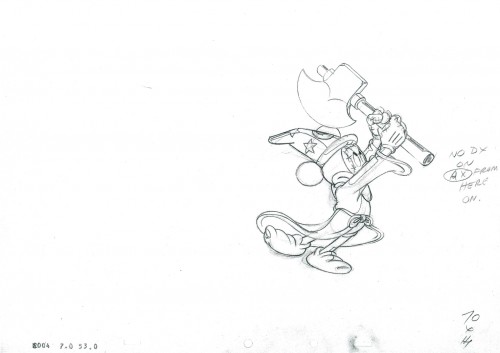

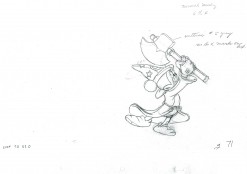

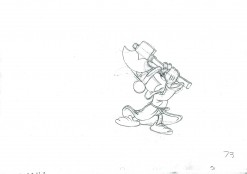

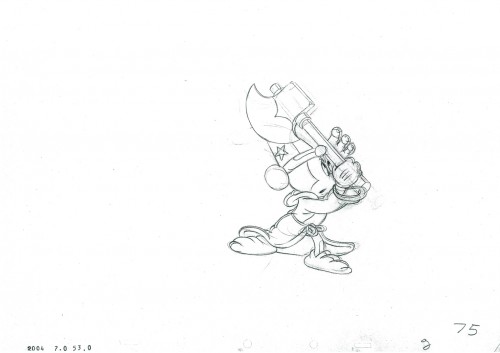

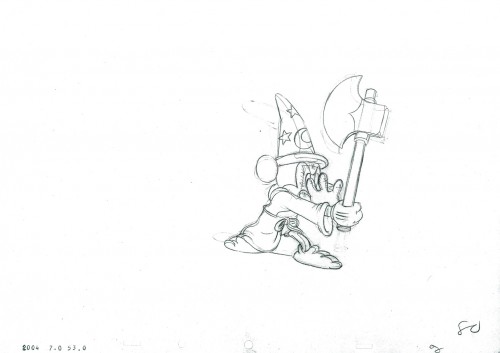

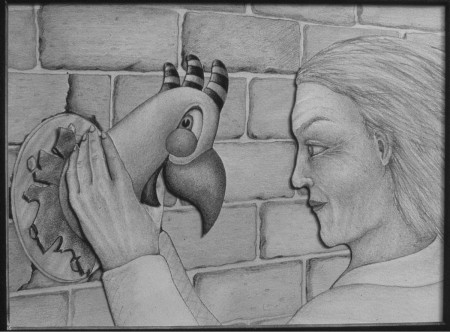

- Lisa Crafts is a brilliant animator, designer, film maker and artist. She’s also an excellent friend. We worked together on a number of films I made in the ’80s, and her scenes still sparkle unlike many others in those films. The humanity she brought to the character of Abel in ABEL’S ISLAND just knocked my socks off. When he found a time piece on the island and brought it back to his camp, he said the ticking reminded him of his wife’s heart; he felt it brought him closer to the partner he’d been separated from. Lisa went a step beyond the layout by having Abel physically embrace the watch. There was just so much warmth in that gesture; it solidifyed the scene and said so much about the character.

Of course, I brought her into the projects because her Independently made films reflected every bit of that warmth, and I knew she would offer so much to the films. She did.

I am proud to host this Q&A and to give a small showcase to her great work

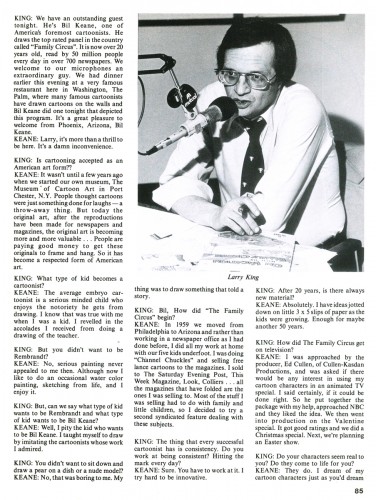

Lisa at the lathe

Michael: Can you tell us a bit about your start? What brought you to animation? Did you go to school for it?

Lisa: I grew up in New England, and was a kid who created imaginary worlds in my backyard, my closet, or in any nearby fallen tree or sandpit. I started shooting photos at age 8, when my dad gave me a camera he got from his friend who owned a pawnshop. In high school, I drew, painted, made pottery, and joined a darkroom class the high school art teacher offered. An experimental filmmaker, Ken Brown, visited our class. He was then making lightshow films for the Boston Tea Party, the premier Boston rock club. He showed us how to make flipbooks and pixilation, my first exposure to animation techniques.

The summer I turned 17, I developed and ran an art school for kids and was commissioned to paint a psychedelic mural on a garage door. As soon as I finished and got a check, I bought a plane ticket to London. I hitchhiked around England and Wales, and had an odd variety of coming-of-age experiences. Returning to the States, I worked an eclectic array of day jobs, and painted or drew at night. One day, while returning some Gregorian chant records to the library, Ken Brown drove by. He beeped, and backed up. He was again teaching in my hometown, had met my sister, and discovered that we both had been to the Isle of Wight music festival in England that summer. He said he had made a movie there. Curious, I got into his 1940 Chevy, and we’ve been together ever since.

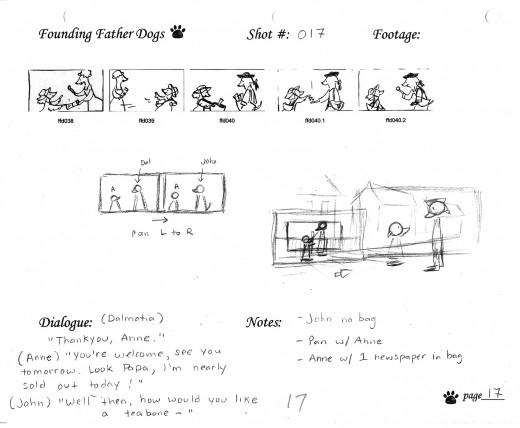

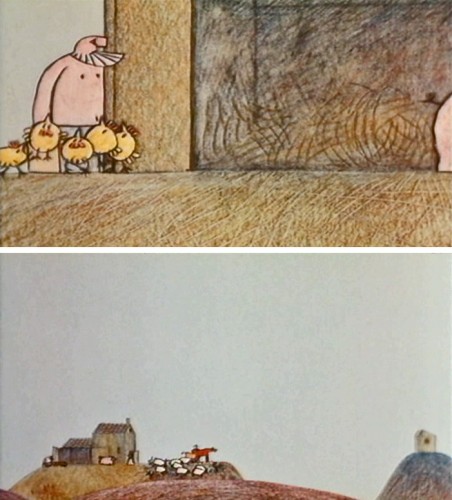

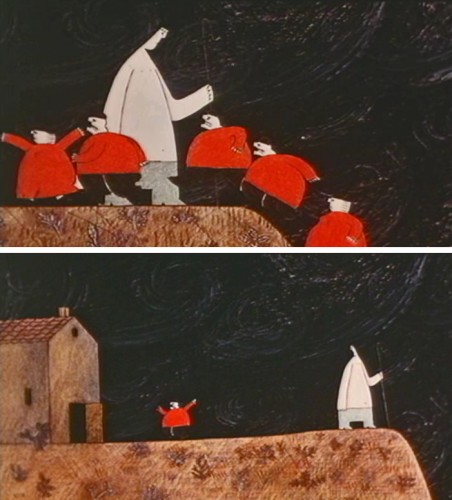

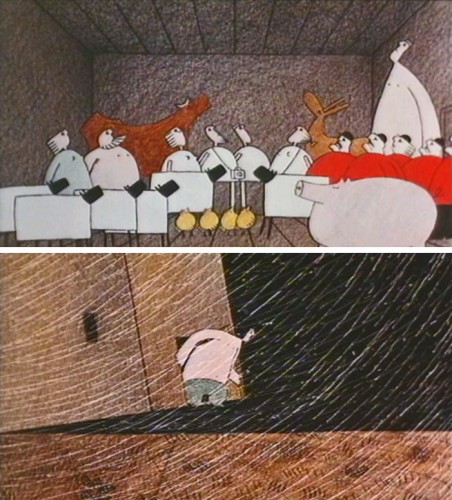

“Desire Pie”

After an extended road trip around Mexico, we moved to Cambridge, and I started making lots of super-8 flipbook and cutout animations. My flipbook films grew in length, and I wanted to learn how to put sound on them. I snuck into the animation class at Harvard with the gracious cooperation of the faculty, and an administration that looked the other way. It was there that I made my first 16mm cel animation with sound, Desire Pie, and met Suzan Pitt, George Griffin, Kathy Rose, and many other animators.

Michael: Your early work seems to have been aggressively sexual (UNGLOVED HAND, PITUITARY, DESIRE PIE) yet you started to move away from this theme with GLASS GARDENS and become more subtly political

Lisa: Perhaps at the time, just being a woman making a film on any aspect of sexuality could be seen as an aggressive or political act. But I prefer the word exuberant. DESIRE PIE is a fun loving explicit sex film, and PITUITARY, a hand colored found – footage film, is a wry and paranoid tale of the myths and misconceptions surrounding body changes in adolescence. UNGLOVED HAND, a cel animation, is a comment on sex role stereotyping.

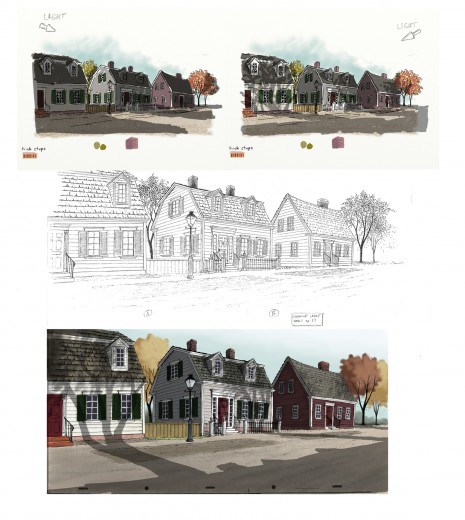

Michael: This film also varied from the others in the cutout style of artwork and the high rendering involved. What prompted this change? Your pre-computer film work varies from more traditional and flat ink & paint style of DESIRE PIE to the very rendered hand-drawn animation of GLASS GARDENS (using cutouts). What determined the style you would aim for in each of the films?

Lisa: After two cel animations, I stopped enjoying drawing hard black lines with flat colors. I returned to cutout animation so I could have the joy of creating obsessively detailed and textured images. I discovered that what excites me in artmaking is going hunting with my camera, constructing evocative environments, and creating emotionally resonant experiences, often laced with social or political issues. My process also involves improvising, inventing, and making stuff with my hands.

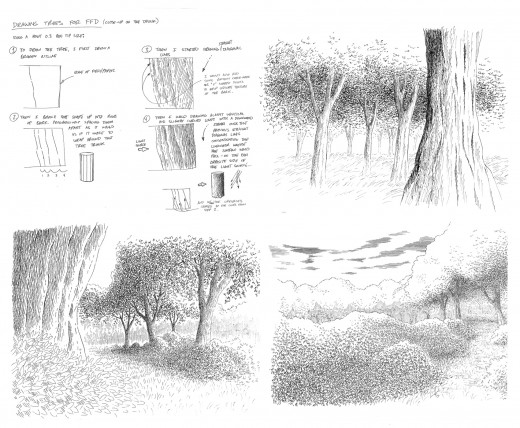

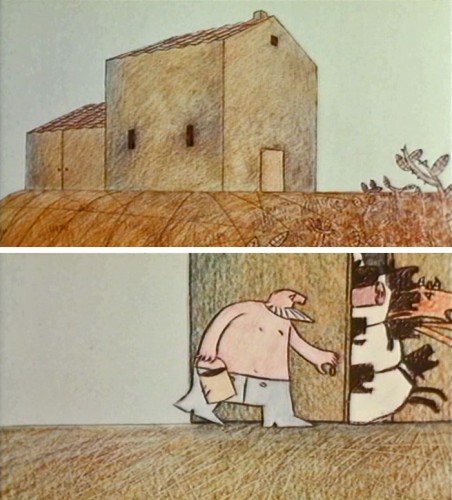

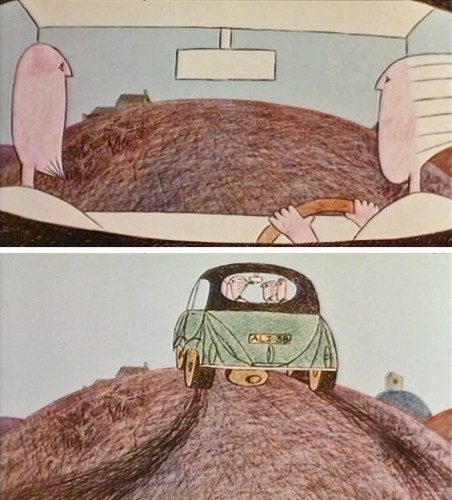

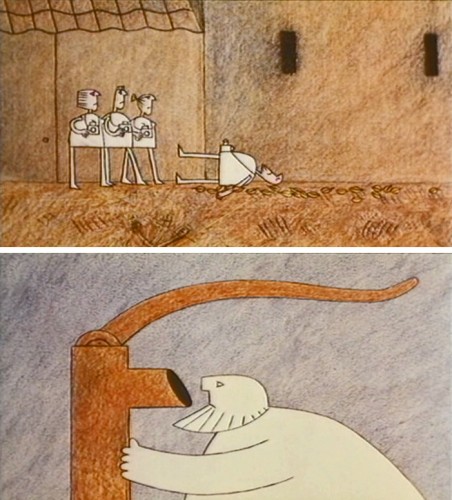

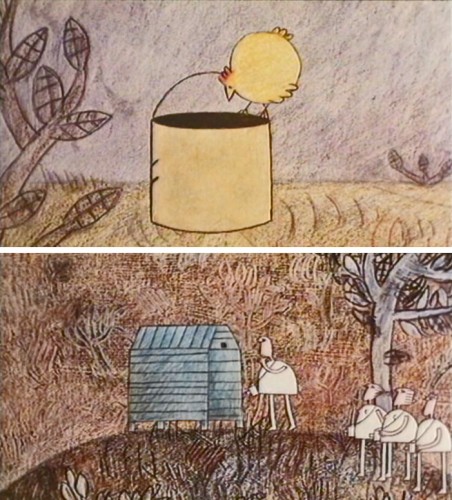

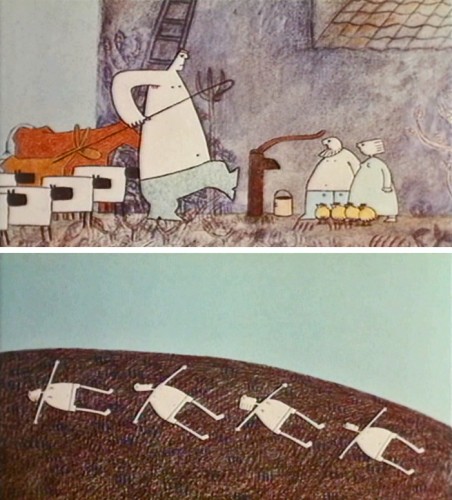

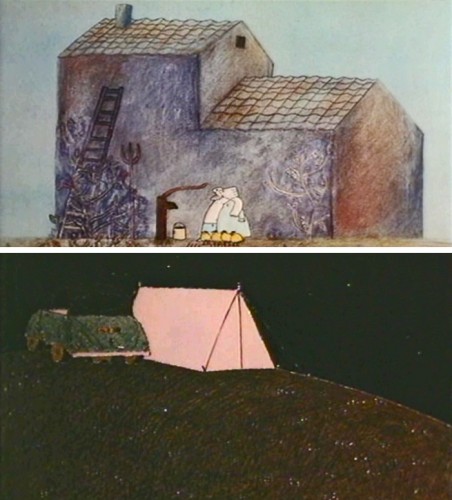

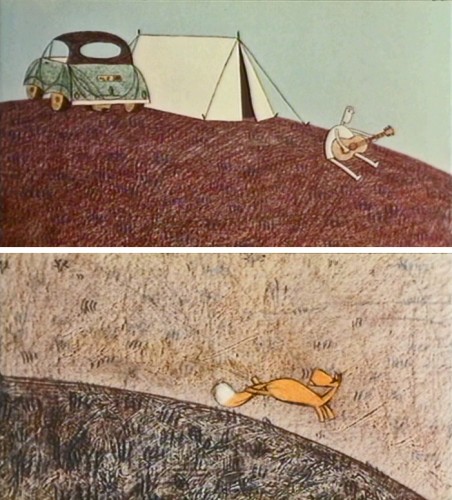

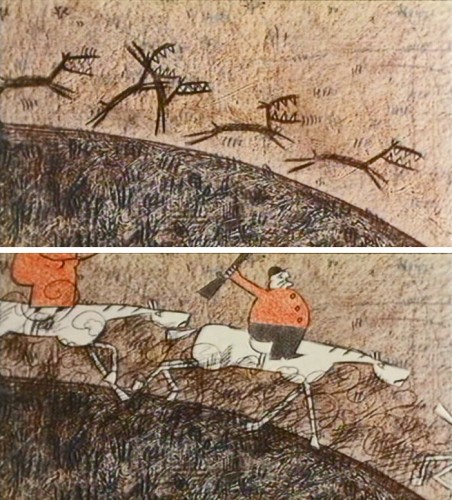

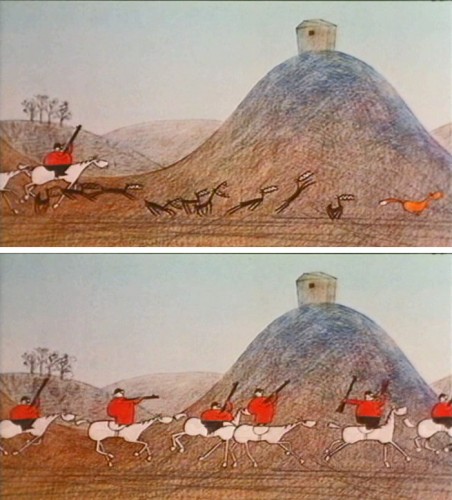

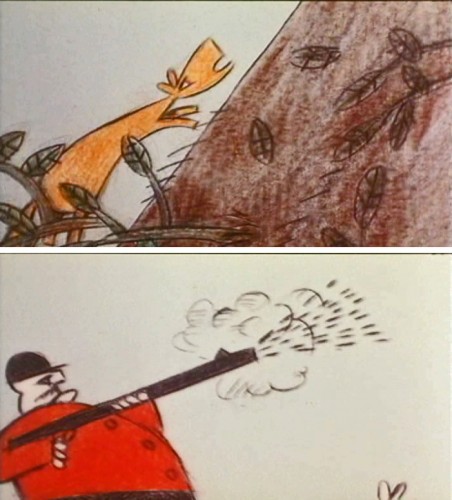

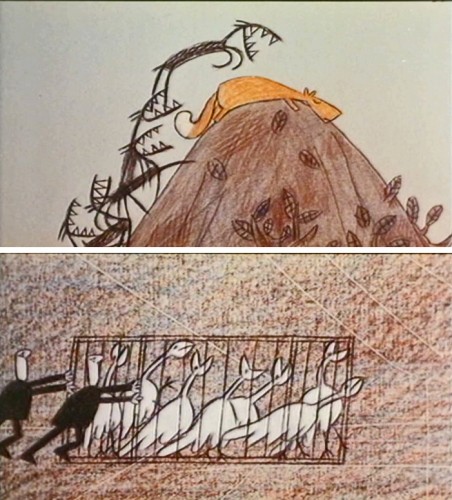

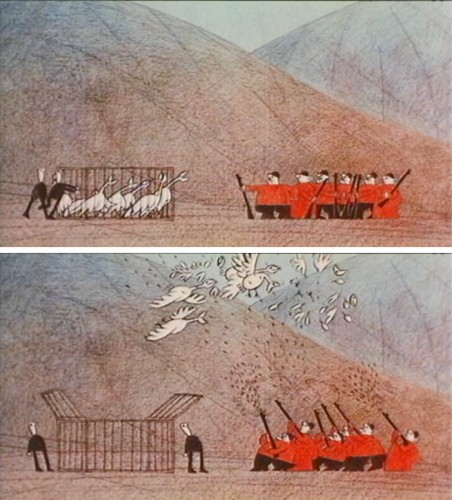

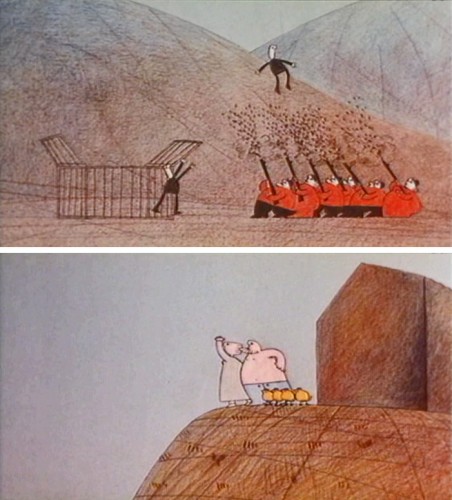

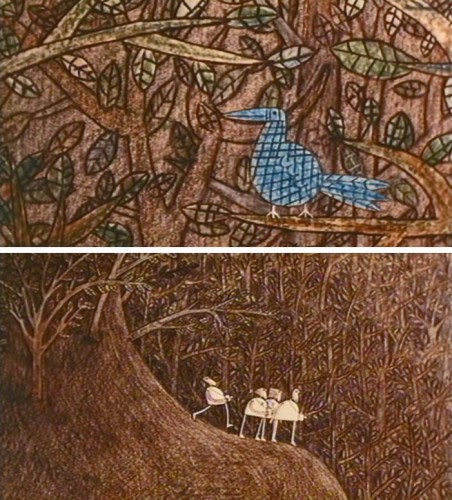

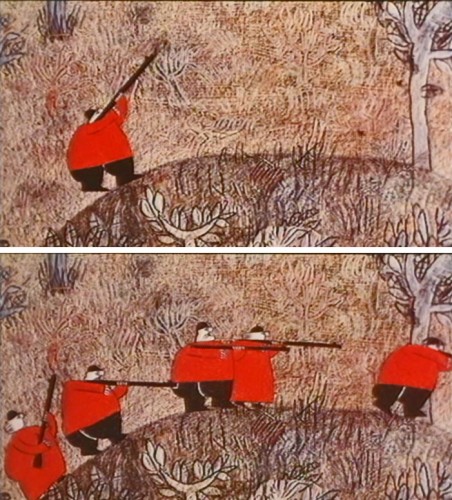

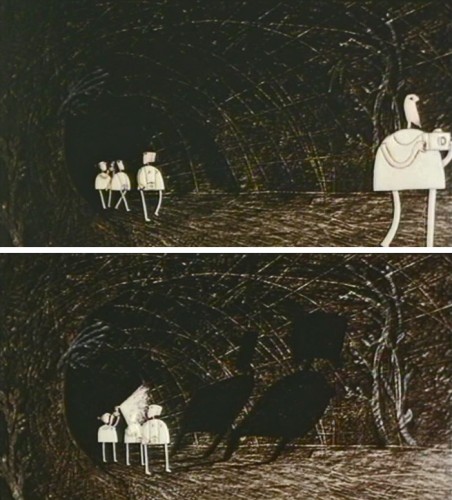

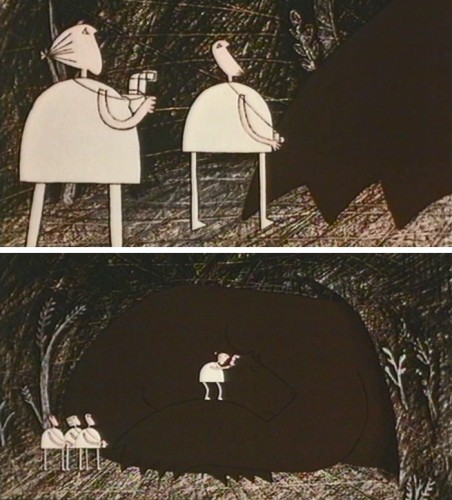

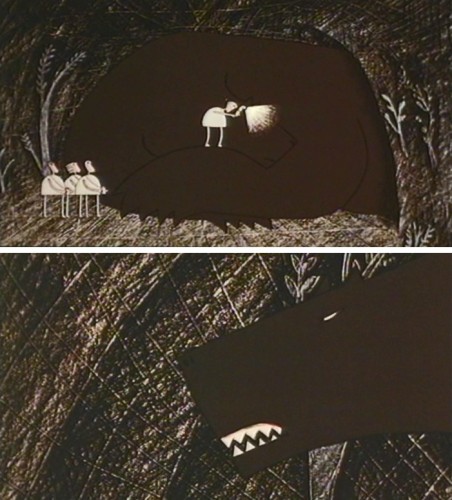

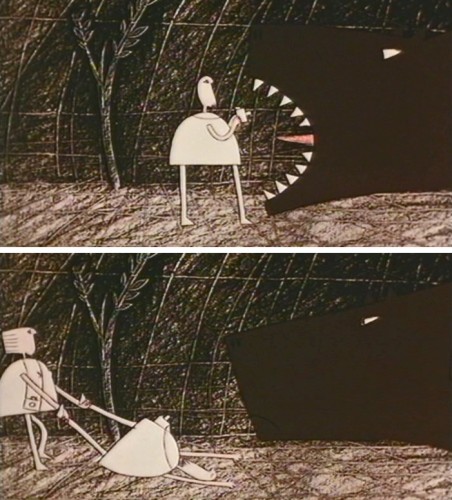

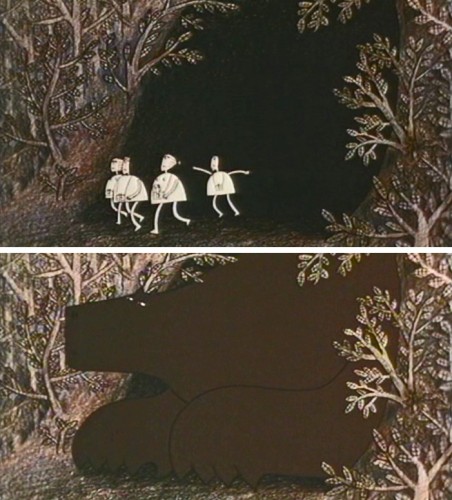

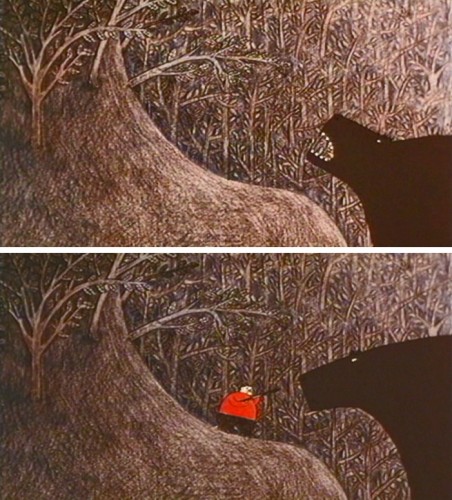

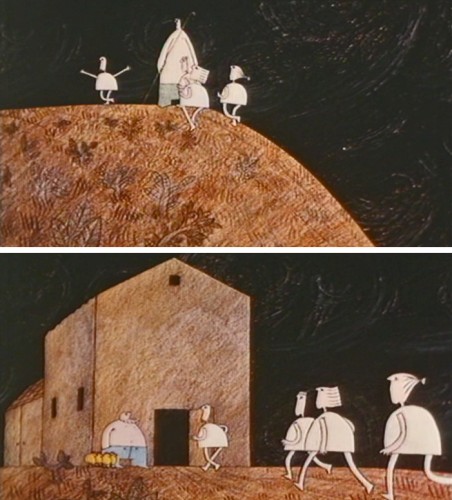

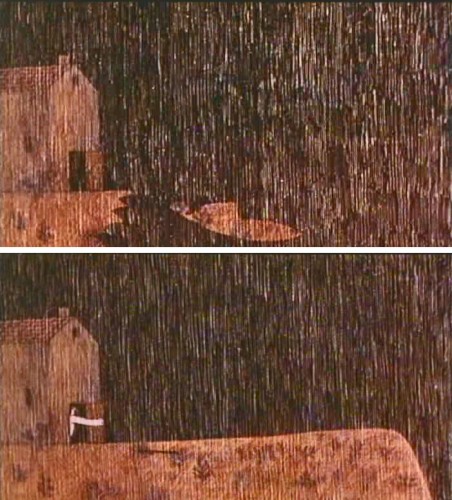

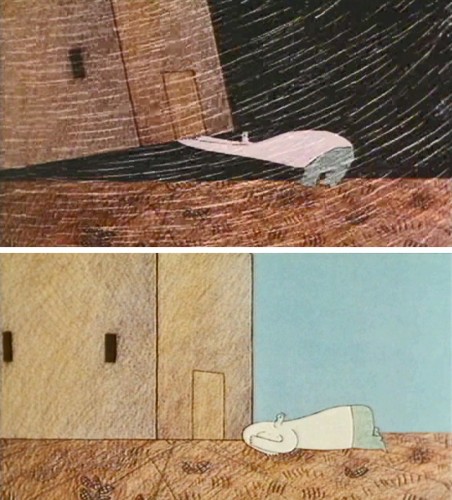

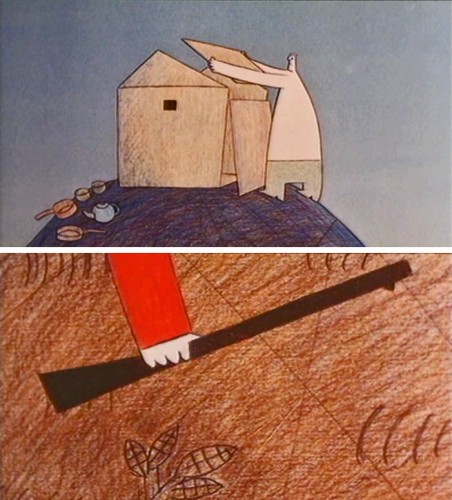

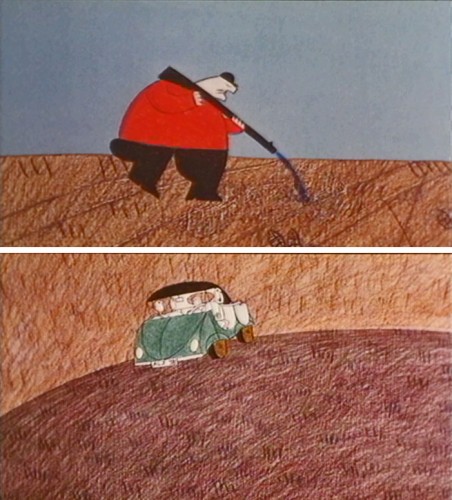

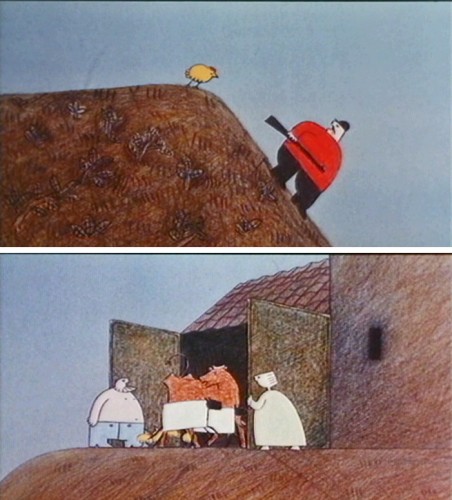

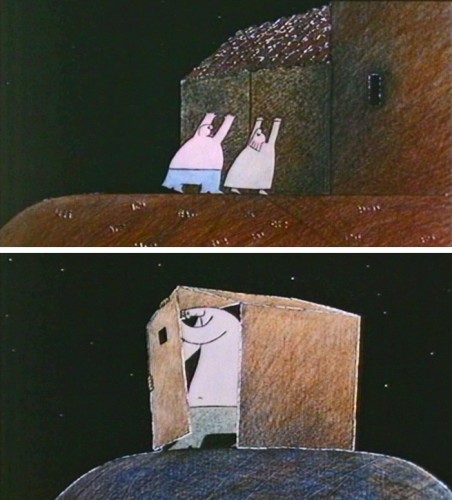

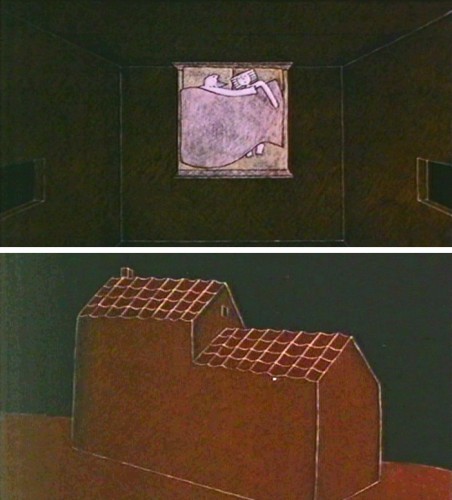

GLASS GARDENS

So I started working on GLASS GARDENS, an allegory about the role creativity plays in the survival of the human spirit. After I wrote the piece, I storyboarded it loosely so I could keep as much spontaneity in the work as was possible, and have creative invention every day. I rode my bike and photographed various background elements, and asked friends to give me objects that I could incorporate into scenes. I drew with graphite on paper, referencing elements from my photos and the objects friends had given me. The landscapes played a large role in this film, as they have in all of my work since then. Just like the play I engaged in as a child, creating worlds that tell a story is an important part of my work.

After nine months, the artwork was finished, but I no longer had access to the Oxberry animation stand at Harvard, and to rent one was prohibitive. I was introduced to Peter Lindenmuth, an amazing Einstein-like inventor, and he looked at the Oxberry, drew up blueprints, and told me that if I worked with him, he would charge me $9 an hour to build one. I spent six months working at Nexus Machine Shop-Gallery with Peter. We also worked with my dad, a carpenter, and together we built the stand that I shot Glass Gardens on. Having my own stand was liberating, I was no longer dependant on stealing in during school breaks or weekends, and had a place to experiment. It also allowed me to help other animators, like Karen Aqua, who lived down the street.

After nine months, the artwork was finished, but I no longer had access to the Oxberry animation stand at Harvard, and to rent one was prohibitive. I was introduced to Peter Lindenmuth, an amazing Einstein-like inventor, and he looked at the Oxberry, drew up blueprints, and told me that if I worked with him, he would charge me $9 an hour to build one. I spent six months working at Nexus Machine Shop-Gallery with Peter. We also worked with my dad, a carpenter, and together we built the stand that I shot Glass Gardens on. Having my own stand was liberating, I was no longer dependant on stealing in during school breaks or weekends, and had a place to experiment. It also allowed me to help other animators, like Karen Aqua, who lived down the street.

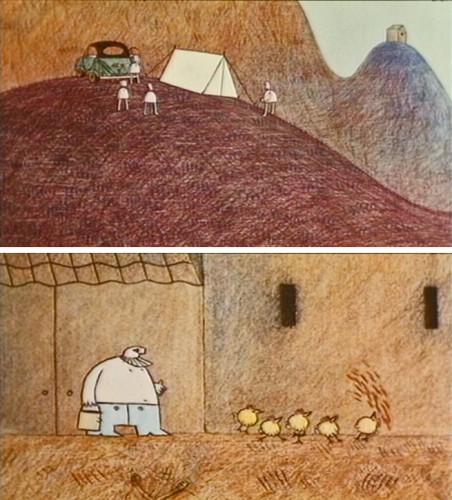

Caleb Sampson performing OCTOPUS’ EXULTATION

After Glass Gardens, I collaborated with composer Caleb Sampson on an hour-long, 3 act music/animation performance called The Octopus’s Exultation. The piece was fairly abstract, with a theme of security and chaos. It was a mixture of cel and marker animation, done on tiny 5 field cels or cards, and drawn in a loose, expressionistic style. The animation was projected with hundreds of hand drawn slides and various lighting effects. We performed it a bunch of times in Boston, and Caleb‘s music became a hit on the local radio stations.

In 1984, I curated a program of American Independent animation and brought it to three cities in Japan. Sayoko and Renzo Kinoshita were the directors of ASIFA in Tokyo, and they asked me to make a film for the first Hiroshima International Animation Festival of peace and love the following year. Reagan was actively rattling swords at that time, and many artists were making work in reaction to the nuclear threat. I wanted to make a film that could reach a wide audience, not just preach to the converted. So I decided to make a commercial for nuclear disarmament, Shout! It was a somewhat subversive project in that I didn’t put my name on, but found an anti-nuclear organization to call it their own, and using their letterhead, got it shown on over 400 television stations worldwide. It premiered at the Hiroshima Animation Festival in 1985.

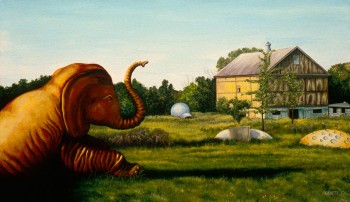

During the years when I first moved to NY, despite working in the industry, I felt I couldn’t afford the time to make another independent animation, so I painted instead. I created quietly disturbing psychological landscapes, which reflect the dreamlike dissonance of the American roadside. As with Glass Gardens, this body of work was referenced from photographs I took when Ken and I travelled America’s blue highways in search of roadside attractions, visionary environments, and vanishing Americana.

During the years when I first moved to NY, despite working in the industry, I felt I couldn’t afford the time to make another independent animation, so I painted instead. I created quietly disturbing psychological landscapes, which reflect the dreamlike dissonance of the American roadside. As with Glass Gardens, this body of work was referenced from photographs I took when Ken and I travelled America’s blue highways in search of roadside attractions, visionary environments, and vanishing Americana.

Michael: Your post-computer animation is certainly more highly rendered. THE FLOODED PLAYGROUND and OVERGROWTH are almost moving into an interpretation of live-action via the animated cutout. Do you feel most content with this work you’ve been doing using computer programs?

Lisa: I’ve always liked dancing on the precipice between the real and the imagined, so yes, the results of working digitally is very satisfying. I can create worlds from a blending of all of my artforms: photography, sculpture, drawing, stop-motion, video and painting. It gives me enormous room for experimentation and discovery.

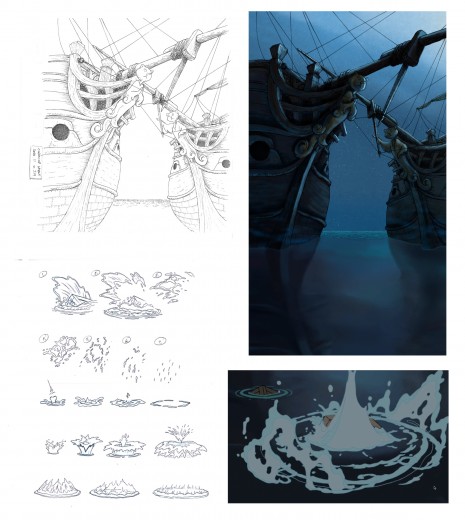

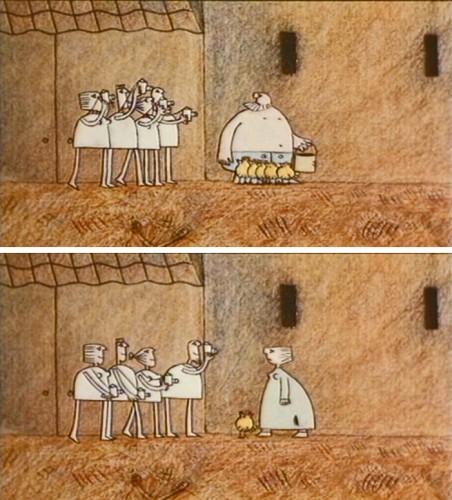

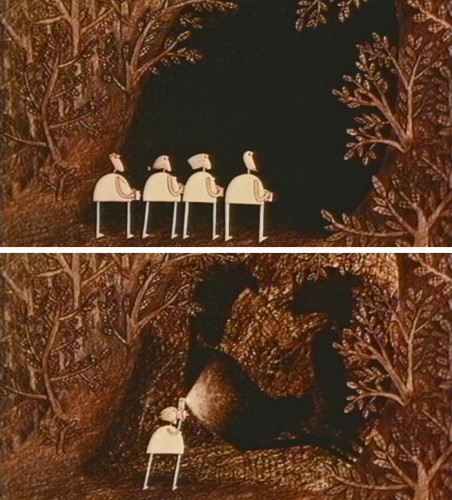

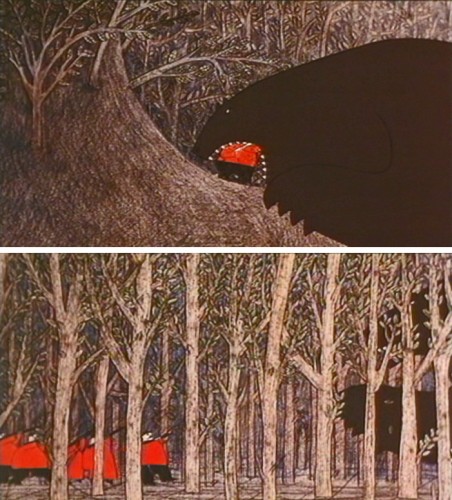

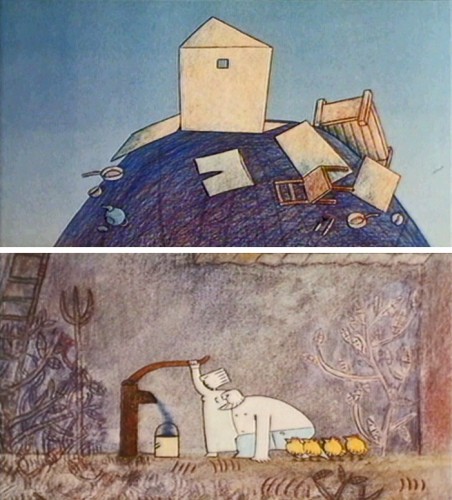

THE FLOODED PLAYGROUND

THE FLOODED PLAYGROUND is about the comforts, terror, and magical thinking of childhood that reside in us throughout our lives. Due to time/money restraints, I could only work on it a few weeks a year at the beginning, but with the aid of some grants, I was finally able to put in the hours it took to complete. During the years I was thinking and writing about it, I carried a scavenger-hunt list of elements I wanted to include, and carried my camera to collect them. I also built some of the sets, caves and creatures. The resulting environments were hybrid, often including elements from different continents, which created the somewhat familiar but indefinable places and times that exist in fairy tales.

Michael: What computer programs are you most likely to use?

Lisa: After Effects, Photoshop, Dragon

Michael: Is the next step cgi? or live action?

Lisa: Not CGI, I’d be 100 years old before that could become a natural and elegant tool for me. Since I’ve used a camera my whole life, tilting into live action is not a big stretch for me. I’m animating live action now, cutting it out from its rectangular shape and/or treating it as individual frames and reworking it.

Michael: You’ve also done a bit of commercial work in animation. A number of Sesame Street films, VH1, MTV and The Electric Company. You worked on staff for me for a while animating traditionally. What do you think of this work as compared to the more personal film work?

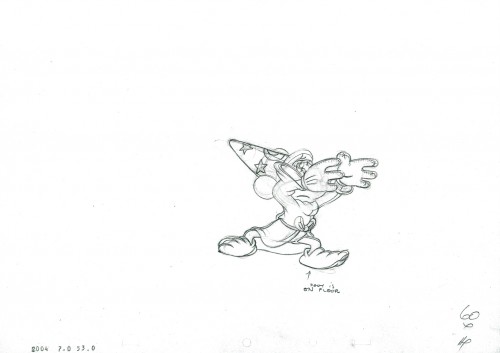

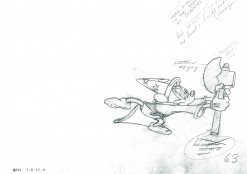

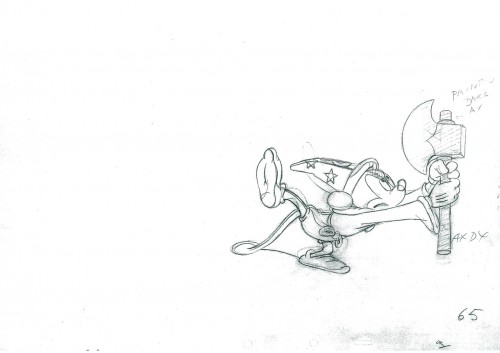

Lisa: Working at your studio was an illuminating experience for me. You hired me despite the fact that I was not a trained character animator. But that trial by fire worked. You treated each animator as a director, and gave us a lot of latitude, and the films reflected that generosity. I got up to speed by the time we worked on Abel’s Island, and felt each scene you handed me was my personal work, and put that kind of spirit into it.

When our projects were over, I finally knew enough people in New York to freelance again. I worked on my own, then partnered with Ken, who was best known as an illustrator at that time. We did some work for music television, and then started working with Sesame Street. It was perfect timing, as our daughter was about 2 years old, and she was able to grow up watching herself, her friends, and our work on Sesame Street. We were so fortunate to have

When our projects were over, I finally knew enough people in New York to freelance again. I worked on my own, then partnered with Ken, who was best known as an illustrator at that time. We did some work for music television, and then started working with Sesame Street. It was perfect timing, as our daughter was about 2 years old, and she was able to grow up watching herself, her friends, and our work on Sesame Street. We were so fortunate to have  the gifted Arlene Sherman as our producer. She allowed us to flourish as artists and to write our own stories and songs, and use our own composers, voice actors, and musicians. Near the end of our time there, I told her that I was transitioning to working digitally, and hoped I could make a new piece in that style. She came to the studio to see what I was working on and gave me the go-ahead to make my first digital piece. I sometimes wonder how it would have impacted my explorations in that direction if she had wanted me to keep drawing.

the gifted Arlene Sherman as our producer. She allowed us to flourish as artists and to write our own stories and songs, and use our own composers, voice actors, and musicians. Near the end of our time there, I told her that I was transitioning to working digitally, and hoped I could make a new piece in that style. She came to the studio to see what I was working on and gave me the go-ahead to make my first digital piece. I sometimes wonder how it would have impacted my explorations in that direction if she had wanted me to keep drawing.

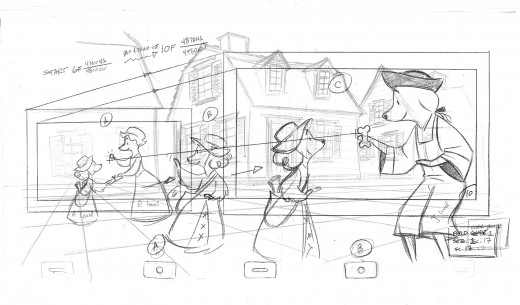

Cindy Kleine’s PHYLLIS AND HAROLD

When I built my animation stand, filmmakers started to come to me to shoot their archival still photographs, and make titles and graphics for their films. I have been working on feature documentaries ever since. In the last dozen years, some of the people I work with have become more adventurous in their use of animation. I am most regularly called on to depict interior life: dreams, memories and hallucinations. I really enjoy the research aspect of the process and being part of a creative team. Recent projects include Cindy Kleine’s film Phyllis and Harold, and Michel Negroponte’s film, I’m Dangerous with Love. I’m currently creating animated scenes for Cindy Kleine’s new doc, The Man in Question, a film about the theater director, André Gregory. While working on I’m Dangerous with Love, I started experimenting with using live action video for some of the hallucination scenes, and so enjoyed adding that spice into the mix, that it triggered my new direction.

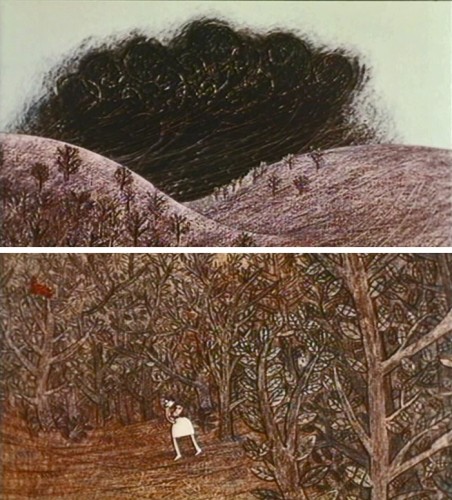

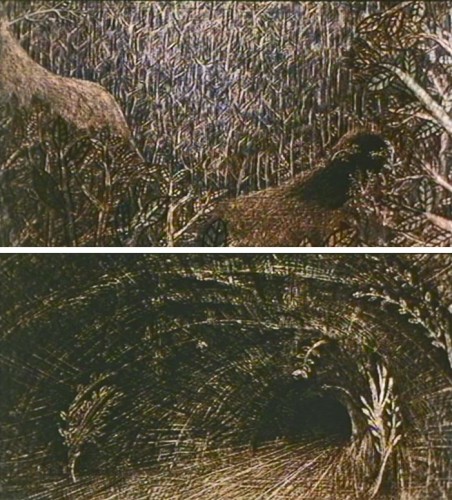

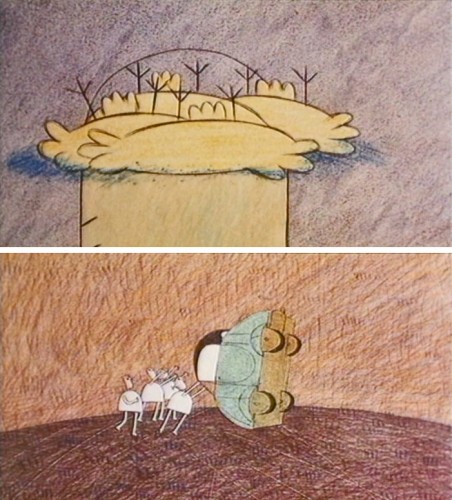

OVERGROWTH is a very slow motion, almost live action play of the wind in the trees and shrubbery depicted in the very realistic montage art. It’s beautiful in its approach and feels like a new direction for you. Do you see it as such? I also notice that this is labeled on your website as “a sketch for a larger work-in progress.” Can you tell us a bit about the direction it’s heading toward?

OVERGROWTH was an early sketch. The new work has some of the same ideas and feeling, but it goes to a different place. It is about coming to terms with the Anthropocene era, a new geologic era that is the result of the actions of humans. I’ve been doing a lot of reading about natural history artist-explorers like Maria Sybella Merian, who in 1699, traveled to Surinam to study, draw and describe the metamorphosis of the incredible insects there. Like Merian, I am engaging with a new world, one reshaped by environmental changes.

Gummibird” from OVERGROWTH

For this project, I go on frequent photographic hunting trips, often urban explorations on bicycle to fringe ecosystems in New York. I now gather video and audio as well as stills. I work in the studio for the stop-motion parts, and sometimes set up outdoor greenscreens as well. I then return to the computer to blend all the elements together. This piece is more poetry than narrative. My work is metamorphosing, and this piece is letting me know that it may not want a sit-down audience, and it may have to be installed, but that is still a question. Although my films utilize different techniques, they have the commonality of exploration, both inner and outer.

OVERGROWTH

Michael: You’ve also worked closely with your husband, the artist Ken Brown. No doubt you are an inspiration for each other, but I also wondered if you’d like to speak about your other collaborations?

Lisa: Our first collaboration was a quixotic attempt at a Felliniesque travelling show called “A Streetside Sensoriumâ€. Well, it never travelled, but we made and sold something for every sense. We built two barnboard movie boxes to show our films, filled and sewed small block-printed muslin bags with sweet balsam needles, made carrot cake, and also sold Ken’s early hand developed photo-postcards and cartoon books. We went to the cobblestone lot in front of a friend’s store in Cambridge on Saturdays, and sold our stuff and came home with enough to live on for the week.

Although we have primarily worked independently, providing each other with critique, assistance and encouragement, we have also collaborated on many projects, both for art and for jobs. We made station id’s for MTV and VH1. We also worked together on Sesame Street, Electric Company, AMC, and a couple of random commercials. Sometimes we closely collaborated, literally passing work back and forth. Other times we broke it down in various configurations, one of us producing, animating and shooting, the other one designing and inking. We determined that whoever wrote a given piece would be the director, in an attempt to avoid the situation of two independent people steering the same car.

Michael: Any other thoughts about the future for your animation?

Lisa: My plan is to keep evolving, it’s all quite a mystery.