Chris Rushworth, whose site AnimalFarmWorld, is dedicated to the collection of material about and from the Halas & Batchelor feature animated film, Animal Farm, has sent me an article he’s found and which I thought extraordinarily interesting. It’s from a UK publication called “Art & Industry” dated September 1953.

Since there were difficulties with the scans, I had to retype the article so it could be legible and I played with the images in photoshop trying to bring some clarity to the sketches. I think they work well enough for this posting.

________________ .

The Designer and the Cartoon Film

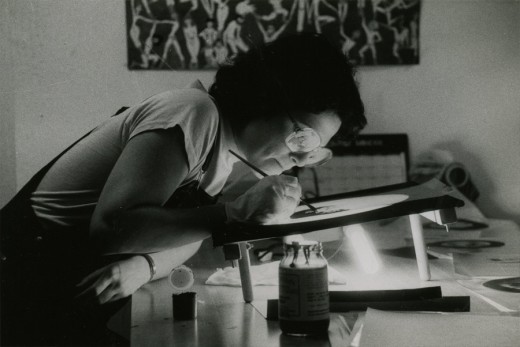

Geoffrey Martin, a senior member of the design team of the

Halas & Batchelor Cartoon Studios, describes his work on the production

of George Orwell’s ANIMAL FARM as a full-length feature cartoon film.

The painter and the film and stage designer work with similar motives but from varying standpoints. One one hand, the painter needs only to justify himself, while on the other, the work of the designer must fit within the framework of another man’s concept. The painter is more or less free to stand apart, and need not e called upon to explain his motives or analyze his emotions. The designer, to achieve his ends is dependent on others, and must therefore rationalize and be able to explain every nuance of his work in order to amplify the trends and emotions in a story and convey them to an audience.

The principles of designing a cartoon film are little different from those involved in a live-action film, With the obvious difference of the medium and its flat dimension, the other elements involved derive purely from the mechanics of animation. Both films set out to tell a story, to corner an idea, and to induce a reaction from the audience.

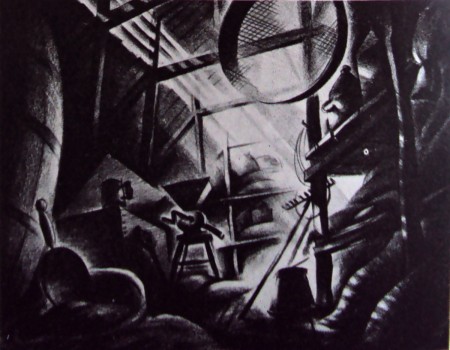

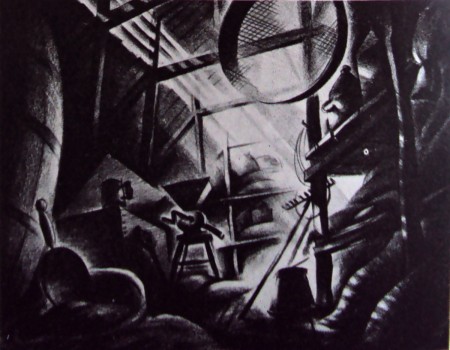

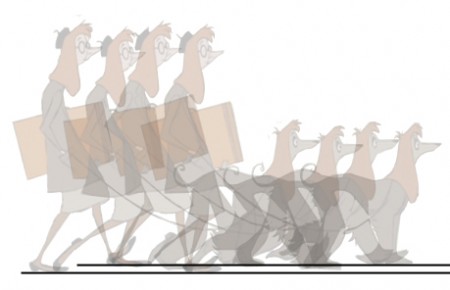

One of Geoffrey Martin’s rough atmosphere sketches

embodying his conception of the farm in relation to the story

in which the animals revolt and dispossess the farmer. The

mood of Orwell’s political satire is excellently captured in this scene.

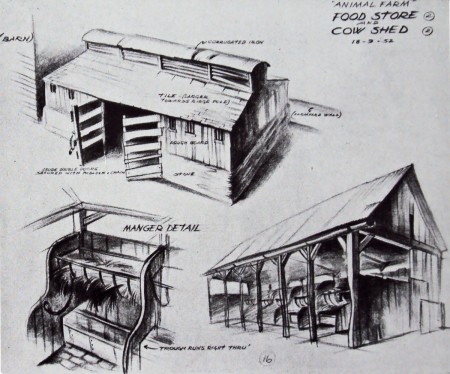

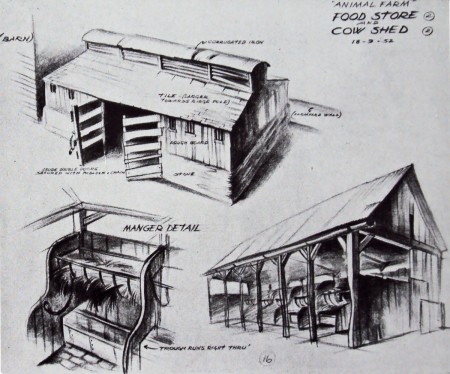

This sketch shows a corner in the farm’s food store

and was created to suggest possible props.

The cartoon designer is, if anything, more directly concerned with, and responsible for, the graphic impression on the screen than the art director in a live-action studio. To him falls the choice of angle of every sot and the responsibility of ensuring that the angle cuts smoothly to another, while constantly preserving the audience’s sense of time and place.

Once having designed and built his settings, the art director on the live-action film is largely in the hands of the director and his lighting cameraman; on these people depends how much of his original attempt is retained in the finished film. It is in this respect that the cartoon set designer is more fortunate; he has much more control over his medium, and is able to assess the result of his work more immediately by seeing the designs in actual use soon after leaving his drawing-board.

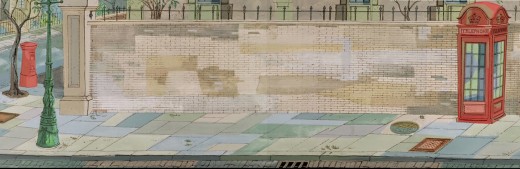

Above: The final interpretation of the scene shown opposite

painted by Matvyn Wright, principal background artist on the

production. Colour heightens the dramatic impact of the scene.

Until comparatively recent years, cartoon films were more or less and American monoply, but just ten years ago John Halas and his wife, Joy Batchelor, set up in London what is to-day the largest cartoon production group in Europe. Wisely, perhaps, they never attempted to emulate the exuberant style of M.G.M.’s ‘Tom and Jerry’ and others who work in similar vein, and as far as the feature field was concerned, Walt Disney, with his lavish and technically superb productions, reigned supreme. Instead, the concentrated on an entertaining series of educational and sponsored subjects with a definite adult flavour.

In late 1951, American producer Louis de Rochemont (‘The House on 92nd Street,’ ‘Boomerang,’ and ‘The March of Time’ series) asked the Halas and Batchelor studios to prepare an animated version of George Orwell’s sharp-edged political satire, Animal Farm. De Rochemont felt the studios to possess a style markedly different from their American counterparts – a style eminently suited, moreover, to what was, to all intents and purposes, a paradox, a ‘serious’ cartoon.

Above: Winter landscape. The half completed windmill

and the farmhouse are shown in this sketch suggesting

the starkness and economy of the settings.

When the studios first embarked on the subject, I was, as a designer, faced with many new problems. For although I possessed considerable experience of short films, Animal Farm was the first feature cartoon to be produced in this country and in length alone, was something completely new to me.

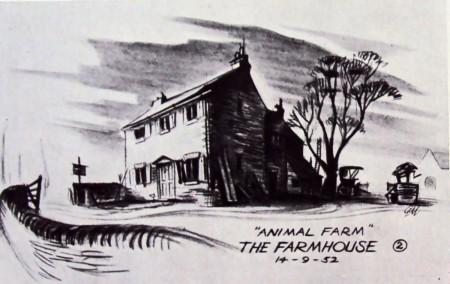

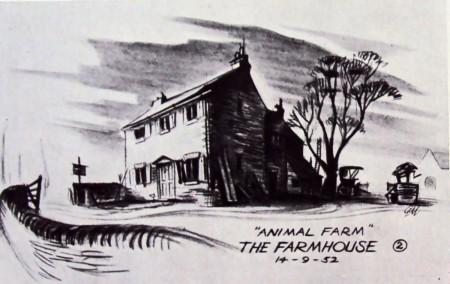

A first attempt to specify the

general style of the farmhouse.

After discussing the story with John Halas and Joy Batchelor, I made a considerable number of atmosphere sketches and rough plans. In these, I attempted to embody our many ideas regarding the conception of the farm in relation to the story.

On reading the book, I had been impressed by the windswept starkness of the farm-qualities contrasting strongly with the warm normality of the local Inn and the village, representing the outside world. We decided that the coulour would eventually go a long way towards emphasizing the contrast between those two main locations.

Since much of the designer’s work is dependent on other departments, I feel that at this point it would be well to describe the production processes of a cartoon studio. Firstly, a word here about animation, itself. In the layman’s view the animator merely ‘makes the characters move’. He does more than that, in effect, he is the very ‘life’ of the film. To make a character move does one thing, but to invest him with the spark of life and a distinct personality is a major achievement, and an element nowadays too often taken for granted.

Audiences have become accustomed to such miracles. Without character there can be no story; the characters within a play are the play. A cartoon film needs a gifted team of animators to bring life and conviction to the characters, and on their work it stands or falls.

To return to actual production, however, the story is broken down into convenient sequences to facilitate handling. In Animal Farm, we have 18 sequences, varying between three and four minutes of screen time each; this represents some 6,400 feet of film in all.

The animation director, who is to the cartoon what the choreographer is to the dance, must then time the action of each scene with stopwatch and metronome. The entire action is planned against a musical score, and to various tempi: so many bars per minute and hence per foot of film.

It is here that the designer enters the picture again. He must work to present the action the director has visualized in the most direct way possible. His department must produce the layout of each scene and the finished drawings of the settings – including sketches of the characters and their size in relation to their settings and notations as to camera movements within the scene.

A panoramic view of the farm – used to establish

the relationship of the outbuildings to the farmhouse.

Sets of the drawings are then passed to the animation team responsible for the sequence. On completion of the work, a test shot is made of their rough drawings.

This test is checked and corrected to refine and smooth out the action. I no drastic alterations are required, the layout drawings are passed to the background department who render them in colour. The animation is traced on to sheets of celluloid and coloured with opaque paint, and the characters on the ‘cells’ are finally united with their appropriate backgrounds under the Technicolor camera.

In planning the finished layout of each scene and staging each individual piece of action, we sometimes found that perhaps the story-line demanded a change in the location of a basic set. Having solved such a problem quite happily, we might then have to rearrange our set as it was originally a demand imposed, perhaps by a later sequence.

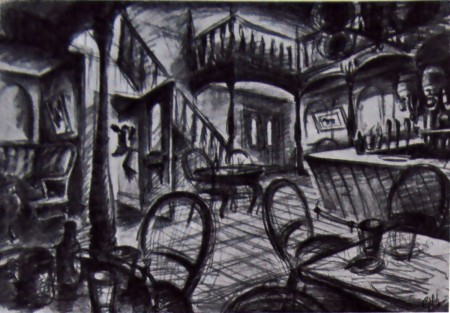

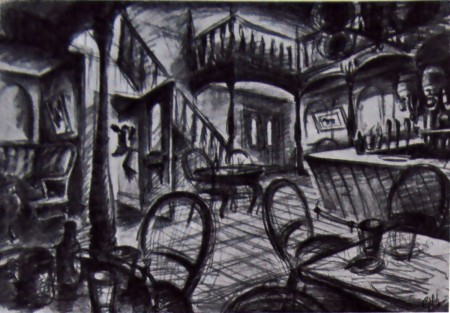

Tentative design for the interior of the village inn.

There is, in fact, a period in every cartoon film when the settings are in a continual state of change and compromise. The designer must bear in mind all the miscellaneous action which takes place in any given location throughout the film and work with this in mind.

The live-action film director is at an advantage in that once his sets are built, the are constant. He can modifu his ideas about camera angles as he goes along. But for us, any slight change of angle withina setting means a new drawing and it is quite possible to accumulate ten or fifteen layouts featuring the same doorway from various angles -made simply in order to stage differing pieces of action.

Such a process involves problems of continuity, for in each drawing ever stone and subtlety of texture must be identical from each angle. Inevitably, it becomes necessary to simplify in order to reduce the amount of work in reproducing every detail; pet ideas are swept away, and like any artist, one is sometimes reluctant to change what one feels to be an eminently satisfactory piece of design. But hard as this may be, there s the final satisfaction of knowing that one’s sets are completely workable.

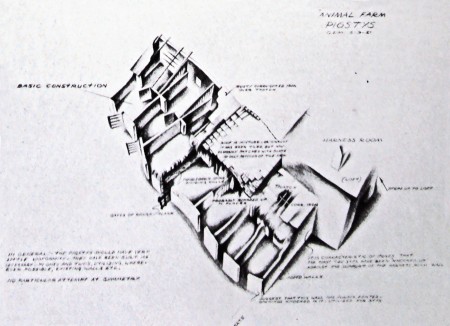

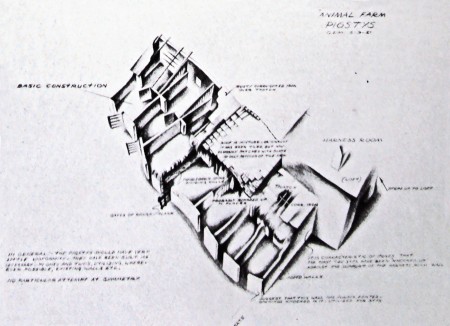

Another atmosphere sketch depicting

the general appearance of the pigstys.

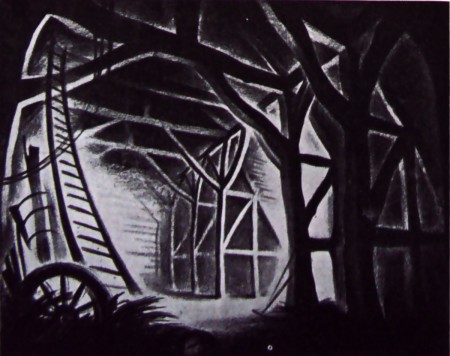

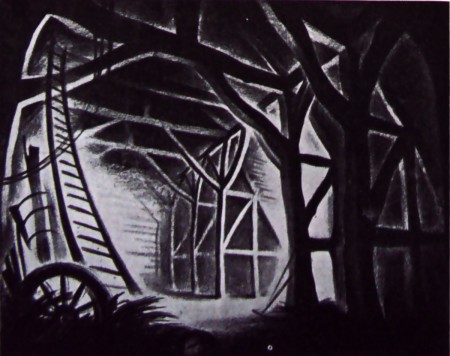

Interior of the great barn, the mise-en-scène

for the planning of the revolution.

Adaptability is, I feel, the first requisite of any setting, whether for stage, film or cartoon. Admittedly, it must carry the fight amount of atmospheric quality, but this must never hamper or dominate the actors – it is essentially a mounting, yet strong enough to be felt by the audience.

Designs establishing the appearance of farm outbuildings

and a detail of one of the mangers.

One of the main problems of designing for Animal Farm has been that the action takes place over a period of years. We have been faced with the problem of reproducing the same settings time and time again – sometimes in bright sunshine, and sometimes, in the depth of winter. It is here that the designer depends very greatly on the background department, and in Matvyn Wright, the principal background artist ont he production, we have been very fortunate. He has a reat feeling for mood and overal texture – qualities with which each of his paintings is invested. It is ovious, of course, that the background painters can make or mar the designer’s work; the effects striven for can be over-stated or lost completely. As an artist he is in the unenviable position of having to work on second-hand ideas. The initial conception is not his, only the interpretation. So often our first rough sketches have a life and excitement that is hard to reproduce.

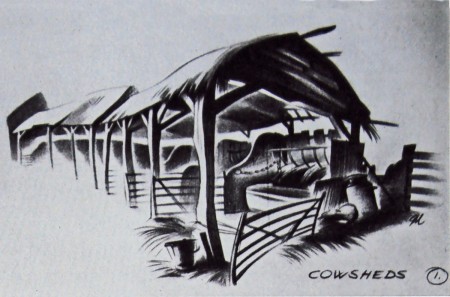

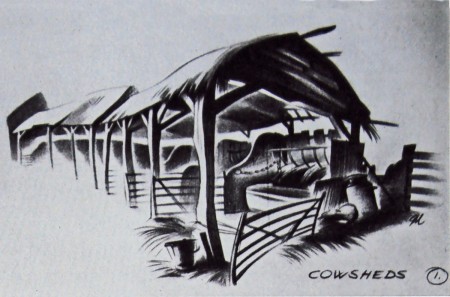

Sketch finalising the type of structure used for housing the cows.

Sketch indicating constructional details of the pigstys.

The reader may now begin to understand that the cartoon studio is a closely integrated unit. It is, in fact, an essentially co-operative art. Although each and every person working on the production is an artist in his own right, we are all, to greater or lesser extent, interpreters, each of us contributing towards the achievement of a common idea.

The designer is dependent on a basic idea, and depends yet again on others to finalize his own individual contributions. The designer depends on the background artist; the animator depends on his assistants to refine his rough drawings, and the people who trace and colour his work. No one thing appearing on the screen can truly be claimed as any artist’s sole property, since we all of us have had a hand in it to a greater or lesser degree. The original conception came from George Orwell’s story – we have interpreted his ideas to the best of our several abilities. The final assessment of the studio’s work rests, as always, with the public.

.

Thanks, again, to Chris Rushworth for passing this article on.

I wasn’t even aware of its existence, but find it quite valuable.

.

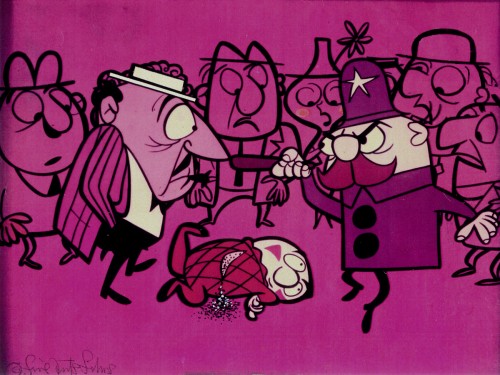

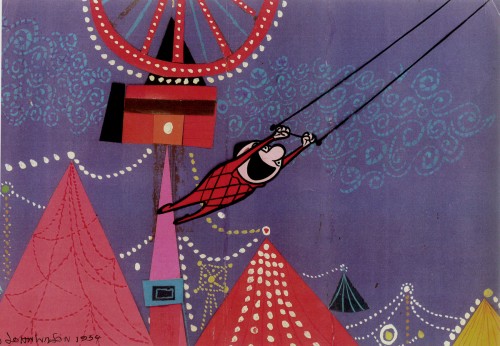

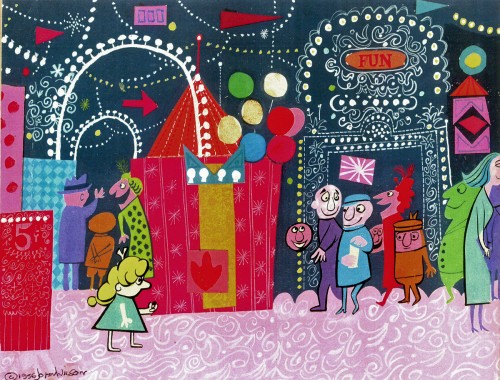

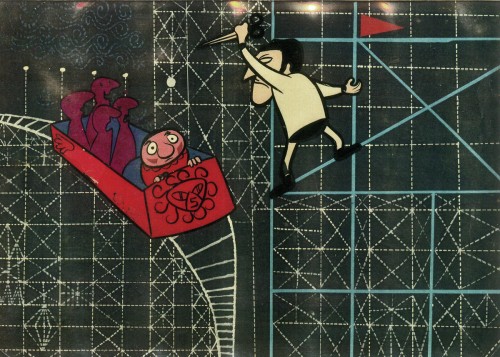

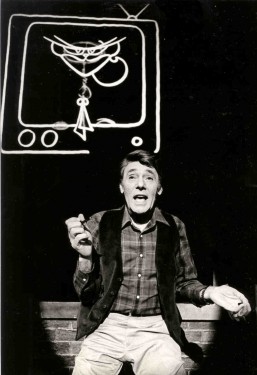

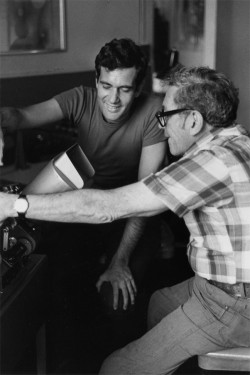

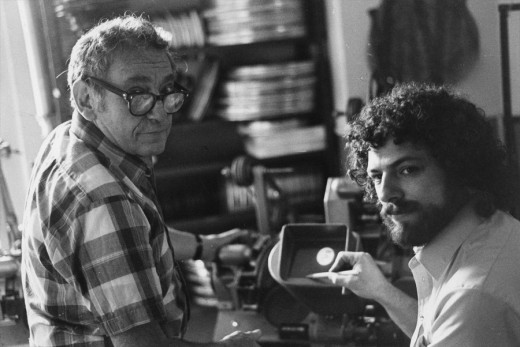

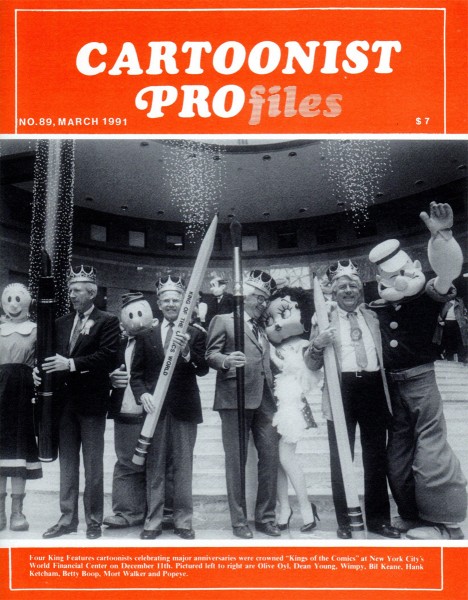

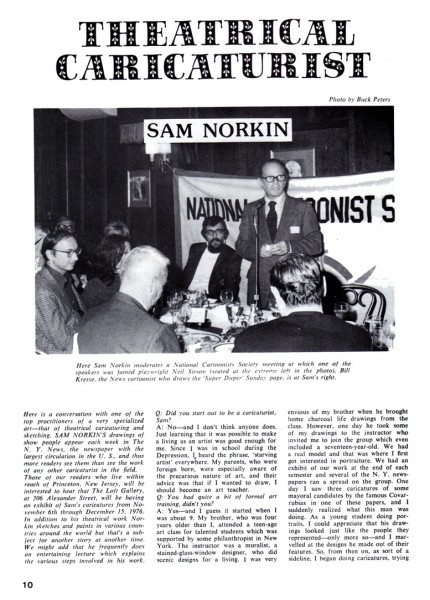

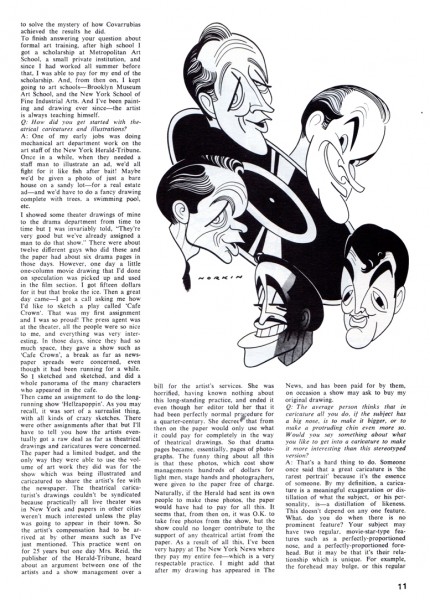

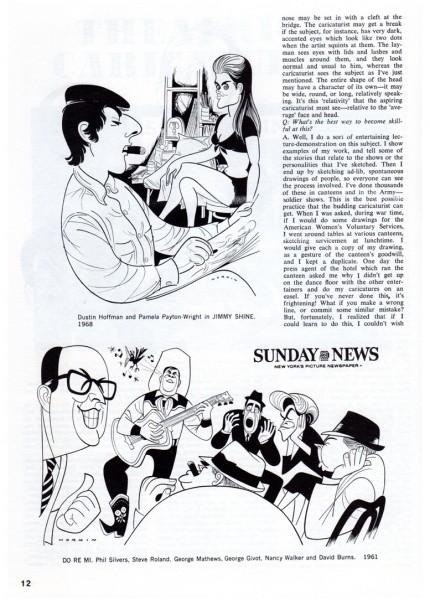

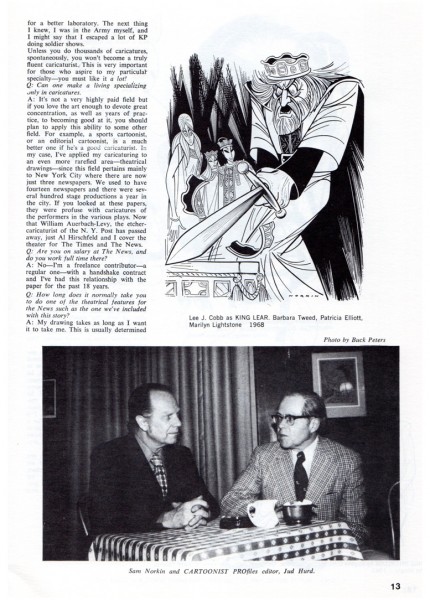

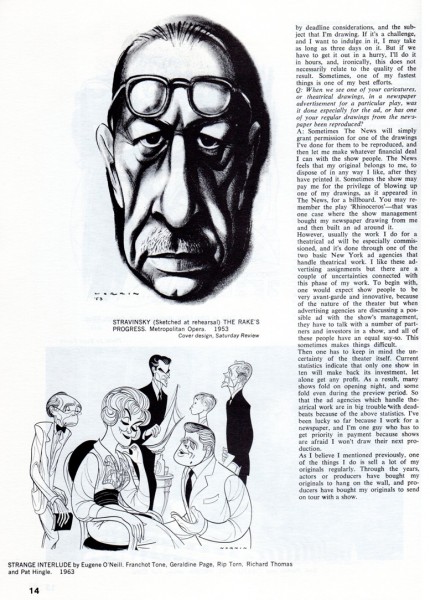

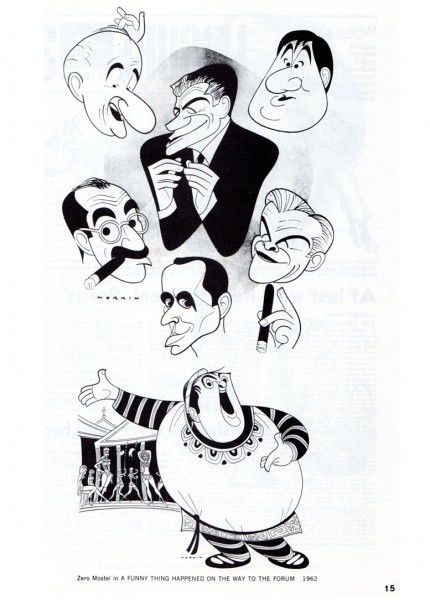

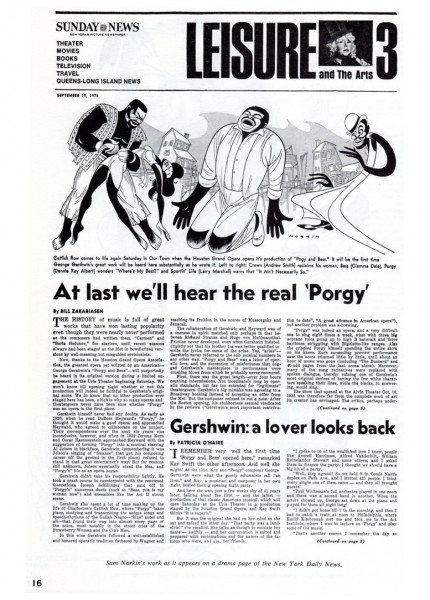

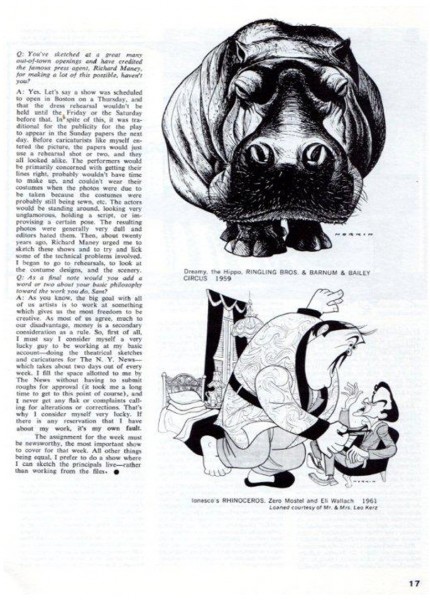

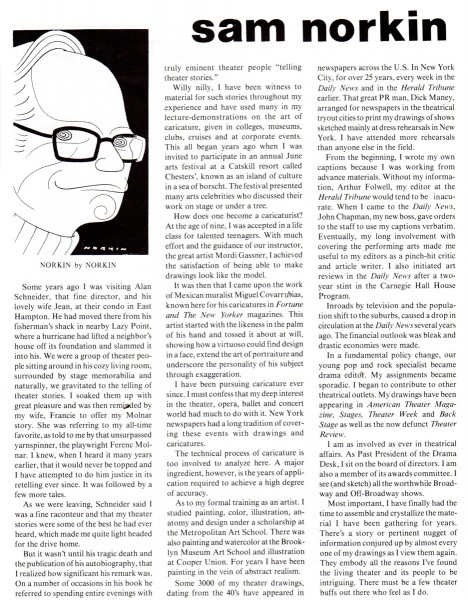

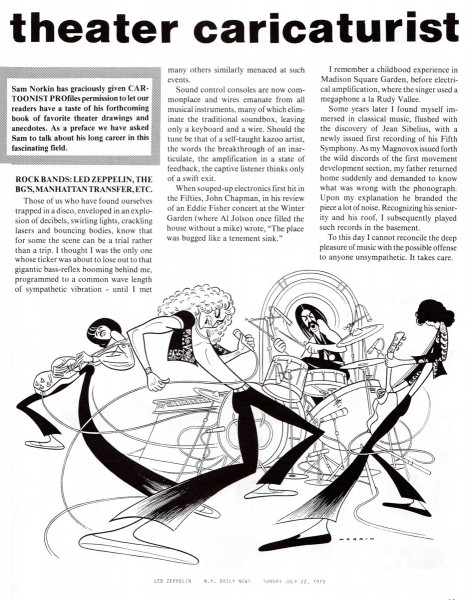

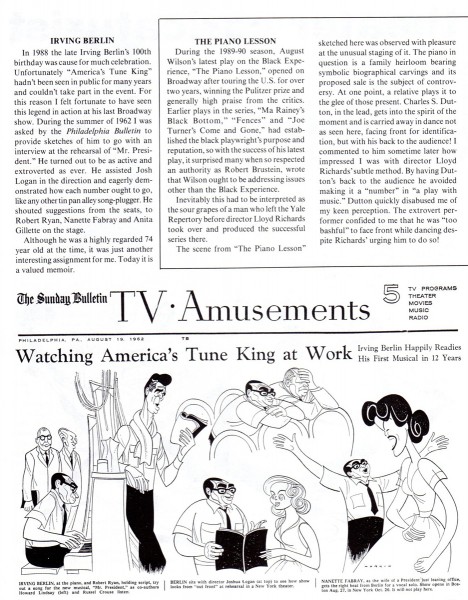

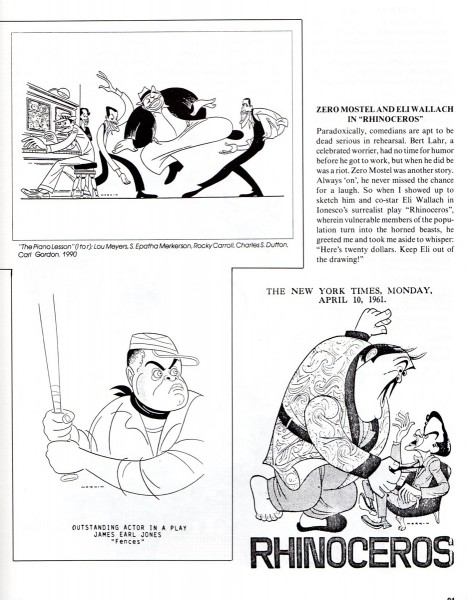

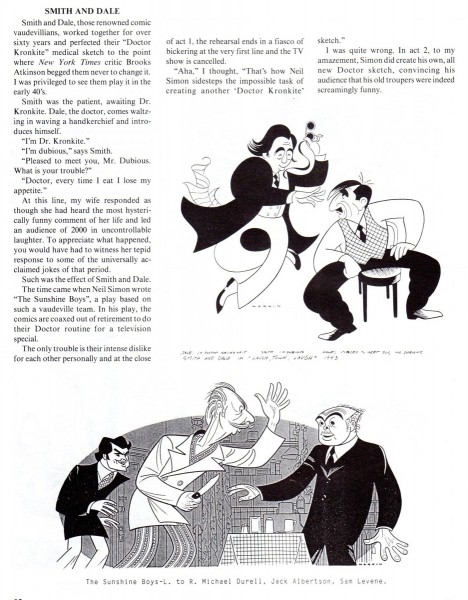

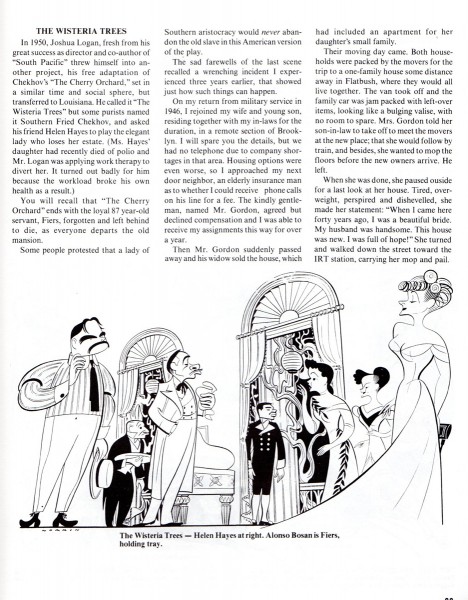

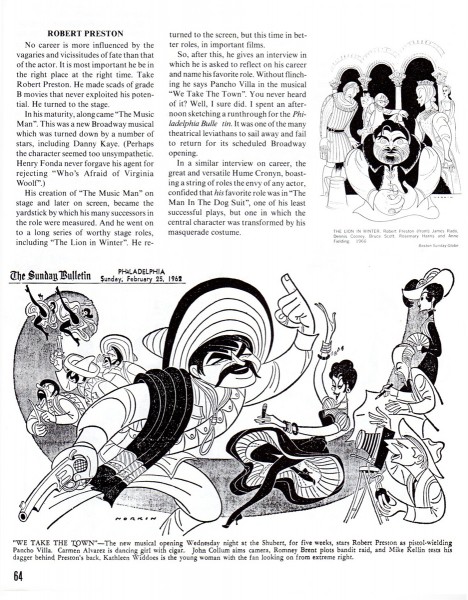

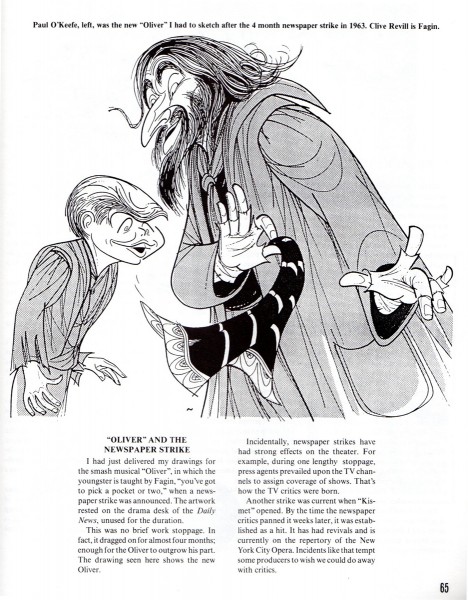

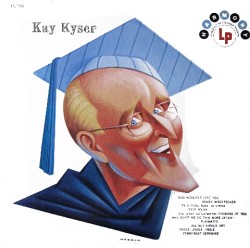

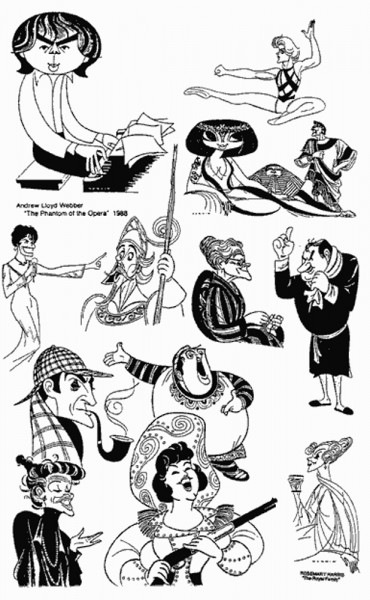

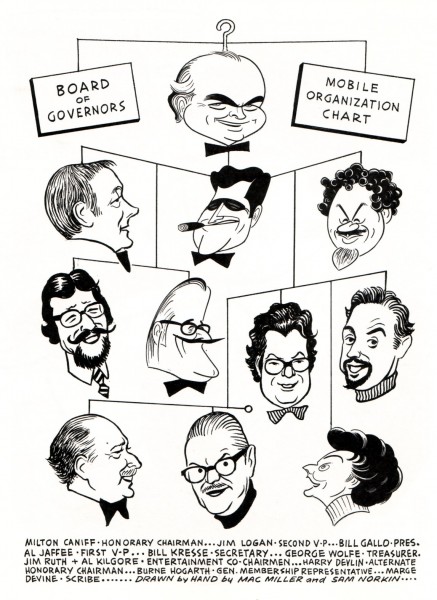

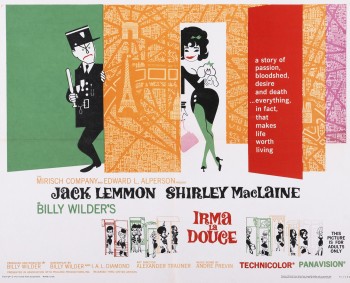

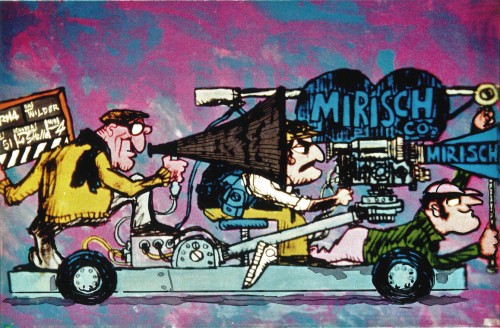

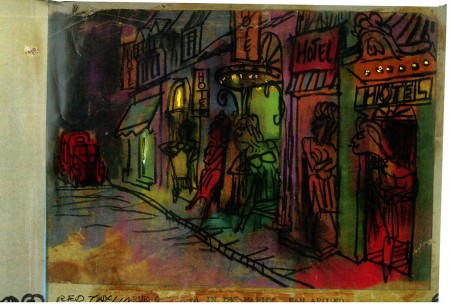

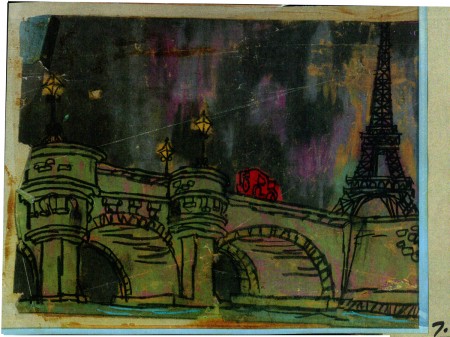

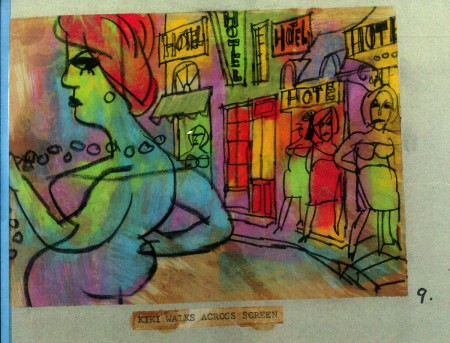

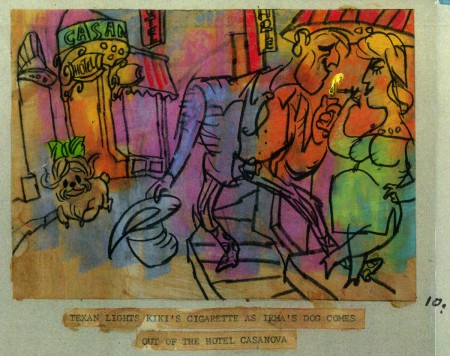

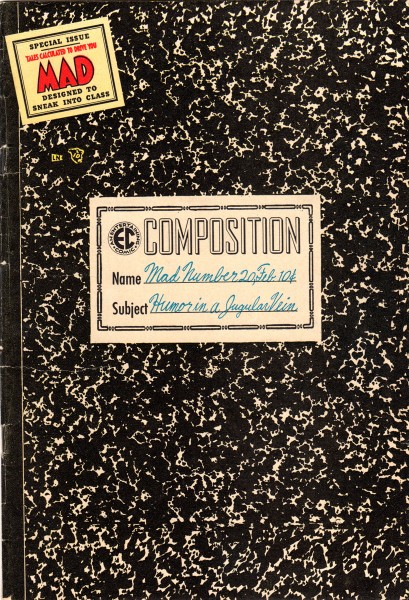

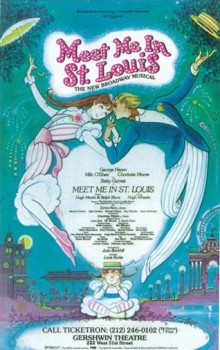

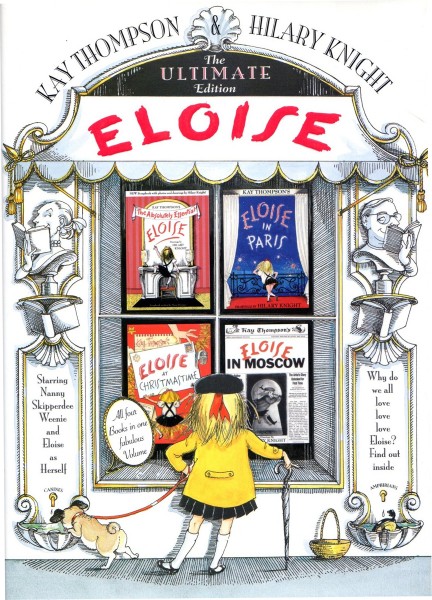

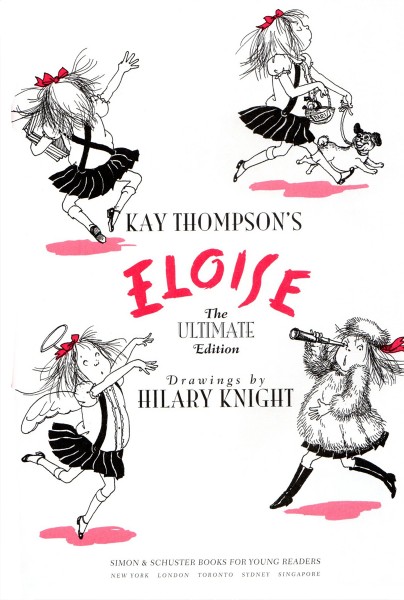

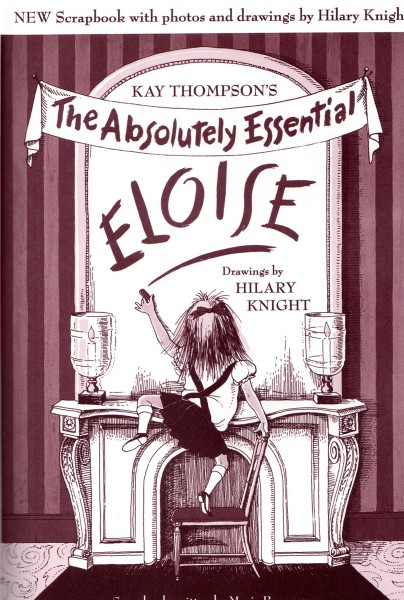

- Sam Norkin was a theatrical caricaturist in the mode of Hirschfeld. Norkin was the house cartoonist for the NY Daily News for many years. Bill Peckmann recently sent me two articles from the Dec. ’76 and the March ’91 issues of Cartoonist Profiles.

- Sam Norkin was a theatrical caricaturist in the mode of Hirschfeld. Norkin was the house cartoonist for the NY Daily News for many years. Bill Peckmann recently sent me two articles from the Dec. ’76 and the March ’91 issues of Cartoonist Profiles.

1

1

1

1

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

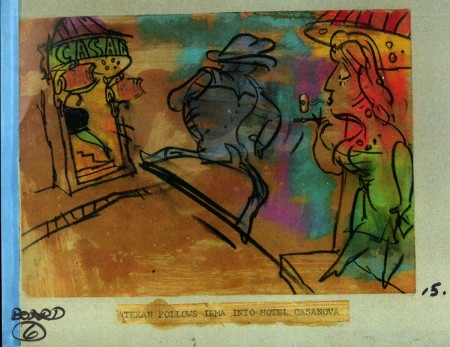

14 15

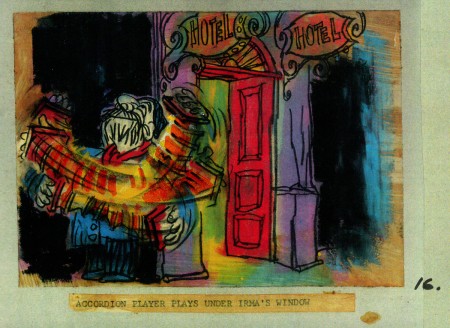

15 16

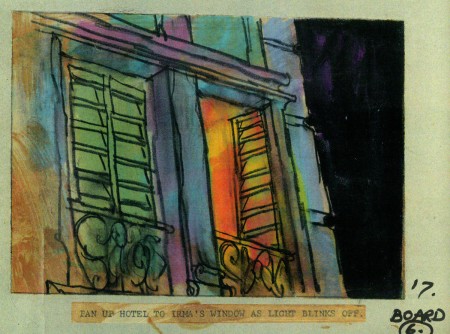

16 17

17 18

18 1

1 2

2

4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 18

18 19

19 20

20