Mike Barrier, on his website, uses a photograph of Walt Disney talking in a corridor to Eric Larson to discuss the state of current day Disney. In the photo, both Walt and Eric are obviously tired at the end of a long and arduous day. Larson remembered, to Mike Barrier, that they were discussing the recently completed feature, Sleeping Beauty, and Walt surmised that at the current expense, he wouldn’t be able to continue to make animated features. That film had cost a bit more than four million dollars in 1958, a whopping sum. (Compare that to the $260 million Tangled cost in 2010.)

Mike Barrier, on his website, uses a photograph of Walt Disney talking in a corridor to Eric Larson to discuss the state of current day Disney. In the photo, both Walt and Eric are obviously tired at the end of a long and arduous day. Larson remembered, to Mike Barrier, that they were discussing the recently completed feature, Sleeping Beauty, and Walt surmised that at the current expense, he wouldn’t be able to continue to make animated features. That film had cost a bit more than four million dollars in 1958, a whopping sum. (Compare that to the $260 million Tangled cost in 2010.)

Mike Barrier‘s point in this article is that features, from that point on, took a slow dip in quality and never recovered. Mike says that he found a falseness setting in to the “sincerity” that Disney requested of his animators, with The Sword In the Stone and Jungle Book being virtually swallowed up by this false “sincerity”:

“I think the falseness I saw was rooted, paradoxically, in that Disney shibboleth ‘sincerity.’ As Walt used the term, during work on the first great features, it was the characters who were to be sincere, that is, to seem to move of their own volition. Over the years, sincerity came to be valued less in the characters than in their animators (and, at one step removed, their directors), until now we are supposed to admire animation because its practitioners—assuming a high level of technical skill—are conspicuously earnest, in a way that many of the great early Disney animators were not.”

I have to agree, for the most part, with this theory. I think it most obvious in the Jungle Book. With The Aristocats, to me, they’d sunk completely and hopelessly off the map. I’ve sat through this film at least half a dozen times and have not been able to stay awake throughout it. The film is not one of my favorites.

Mike Barrier takes The Sword In the Stone as the first full on example of this problem, whereas I love that film, though I admit that it has significant problems. I agree with him on the next one, The Jungle Book, but Andreas Deja would disagree heartily – it was this film that convinced him to become an animator.

I remember discussing Beauty and the Beast with John Canemaker and my saying that I had trouble enjoying it, finding an ugliness in most of the characters – those townspeople cannot be drawn more poorly. But then John asked me if I didn’t think that this would be a film that would encourage lots of young people to want to become animators just as we had been inspired by some of the films of the fifties. It was obvious that I had to agree immediately.

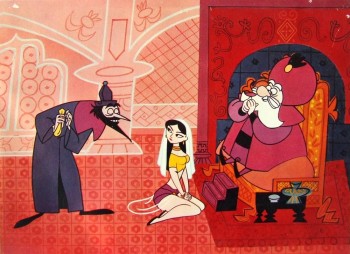

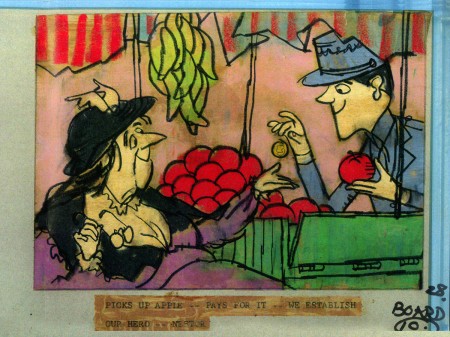

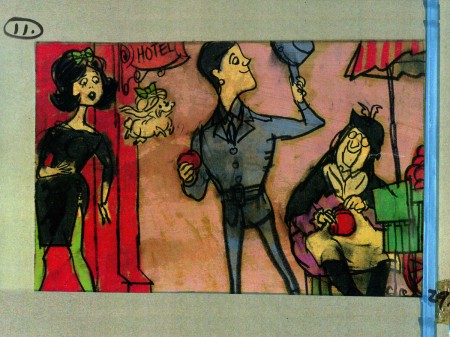

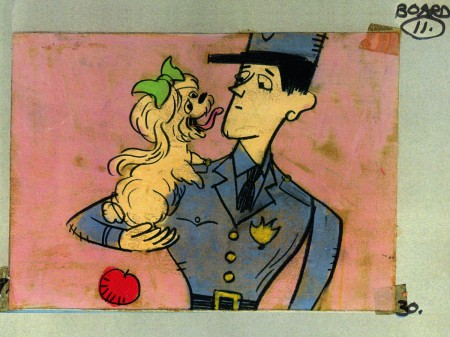

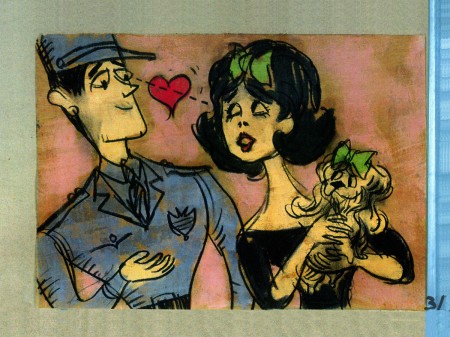

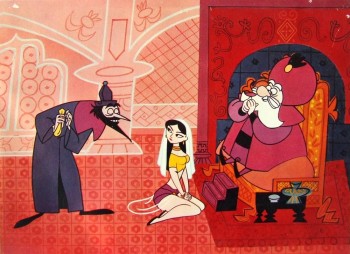

I recognize that The Sword In the Stone was right at the time that I was in love with most of the fare coming out of Disney’s studio, as a matter of fact out of most studios. 1001 Arabian Nights with Mr. Magoo was certainly an influence on me.

I recognize that The Sword In the Stone was right at the time that I was in love with most of the fare coming out of Disney’s studio, as a matter of fact out of most studios. 1001 Arabian Nights with Mr. Magoo was certainly an influence on me.

One of those commenting on Barrier’s column, Garry Apgar, points to Ichabod and Mr. Toad as one of the best of the Disney films, “I was enthralled by the magic of both, and to this day consider the Toad half of that combo picture, “pound for pound” . . . the greatest Disney cartoon ever. I still have the Giant Golden Book edition of that story.”

Personally, except for the ride of the Headless Horseman, I find very little inspiring in that feature. I’d guess that Mr. Apgar was influenced because he saw the film at a time when he was strongly influenced by it, just as I saw The Sword In the Stone at a susceptible time in my life. However, despite that, I have difficulty finding much bad in the film. Yes, I hear odd echos in some of the voice track; the music is completely anachronistic, and some of the animation is not up to the work of the past. I’ll even say that I have a major problem with the wizards’ duel in that the mad Madame Mim is introduced late in the film just for the sake of the set piece, the duel. She’s then dismissed. I have always found that a wart in the storytelling. Somehow the late introduction of the squirrel females doesn’t bother me. Perhaps because they’re squirrels.

Basically, I’m saying that we’re all affected by our influences – not necessarily the quality of the actual film. Those who have seen The Aristocats at a vulnerable time in their lives, probably like that movie, and I can’t really fault them though I know it’s not a benchmark in Disney animation, and, in fact, is definitive proof of Barrier’s theory about the false “sincerity” in the animators’ work and, more to the point, the director’s work. (I can remember Ken Anderson, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston talking about the disco-lights used in the jazz-in-the-attic section of the film. Woolie Reitherman could not be coaxed out of the 70s effect despite the fact that it was already dated when the film was released.)

Basically, I’m saying that we’re all affected by our influences – not necessarily the quality of the actual film. Those who have seen The Aristocats at a vulnerable time in their lives, probably like that movie, and I can’t really fault them though I know it’s not a benchmark in Disney animation, and, in fact, is definitive proof of Barrier’s theory about the false “sincerity” in the animators’ work and, more to the point, the director’s work. (I can remember Ken Anderson, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston talking about the disco-lights used in the jazz-in-the-attic section of the film. Woolie Reitherman could not be coaxed out of the 70s effect despite the fact that it was already dated when the film was released.)

But back to the comments section of Mike Barrier’s site. Jim Korkis was surprised while teaching Animation History to a number of young interns at the Disney studio. “They had no acquaintance with any silent animated cartoons that were the foundation nor any of Walt’s competitors in the Thirties and Forties like Paul Terry, Warner Brothers, MGM and others. Even as the class approached the beginning of computer animation, they had no clue how and why computer animation developed.”

But back to the comments section of Mike Barrier’s site. Jim Korkis was surprised while teaching Animation History to a number of young interns at the Disney studio. “They had no acquaintance with any silent animated cartoons that were the foundation nor any of Walt’s competitors in the Thirties and Forties like Paul Terry, Warner Brothers, MGM and others. Even as the class approached the beginning of computer animation, they had no clue how and why computer animation developed.”

This has become the state of the world. It’s not only animation. Just focusing on the Arts, I see it everywhere.

- There’s no knowledge of Vaudeville among the young performers and creators trying to sell their wares to theatrical shows. When Stephen Sondheim, Charles Strouse and John Kander die so will the history of the theater.

- I wonder how many architecture students have read Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead.” Certainly not for the confused libertarian views, but for the threat of two different architectural forces that dominated the world in the early Twentieth Century.

- How many Fine Artists explore early Renaissance Art, except within their Art History classes? Do they question why and how Daumier painted as he did? What about Turner, do they understand what he was trying to do? Or David? This is our history; it’s the foundation of the future. Only by going through his apprenticeship to Thomas Hart Benton could Pollock paint his splatter paintings.

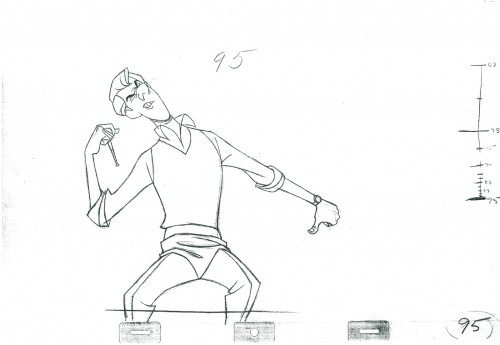

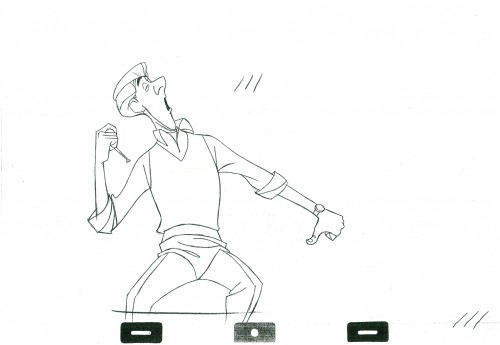

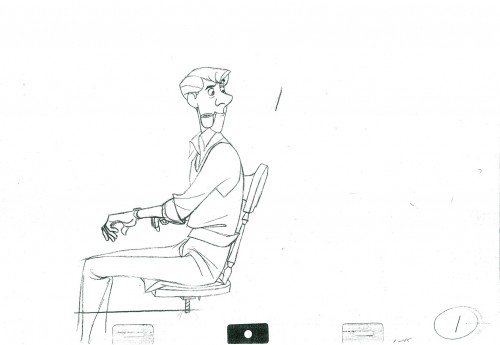

Animation students should do more than study scenes that have already been animated. By limiting yourself to how Milt Kahl or Tex Avery did something, you’ve eliminated the world. This is what you’re caricaturing in your animation, I should think. Regurgitated Jim Tyer is not only not art but it’s not Jim Tyer. And it’s not good. Art Babbitt, while at the Disney studio, took piano lessons and dance lessons knowing that it would help his animation, and undoubtedly it did. It’s more important to take those dance lessons (and more fun, too) than it is to study all of Tytla’s scenes.

I’m not saying that animators shouldn’t study past animation, but what I am saying is that it’s the world outside your body that is shaping any artistry within you. Imitating Chuck Jones’ blinks won’t help you other than knowing that Jones did it that way.

I’m not saying that animators shouldn’t study past animation, but what I am saying is that it’s the world outside your body that is shaping any artistry within you. Imitating Chuck Jones’ blinks won’t help you other than knowing that Jones did it that way.

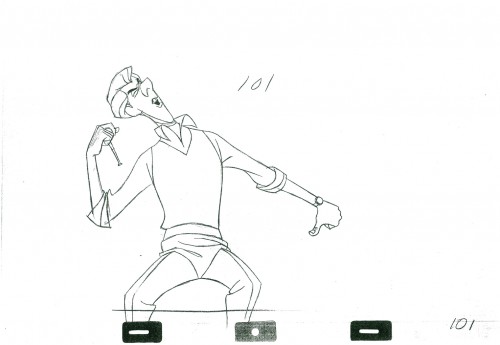

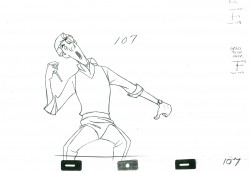

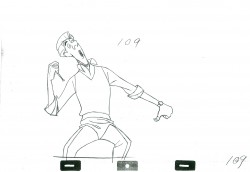

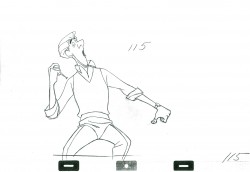

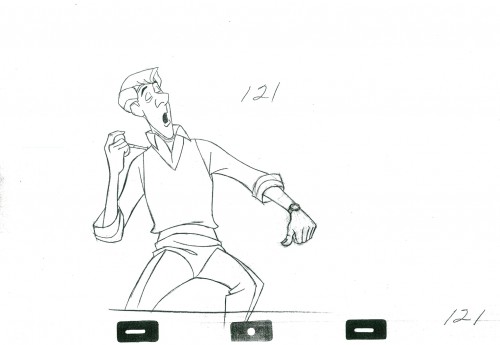

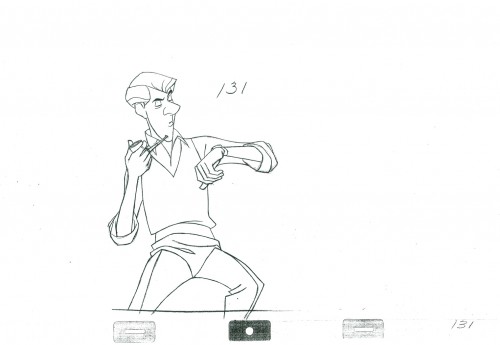

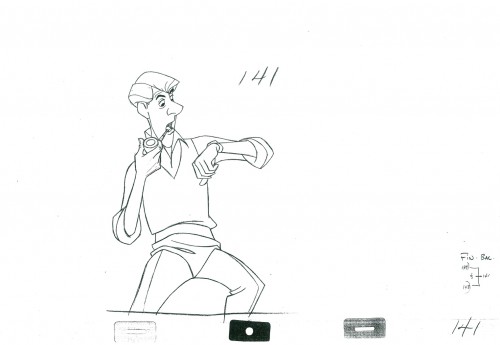

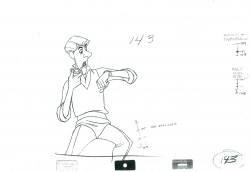

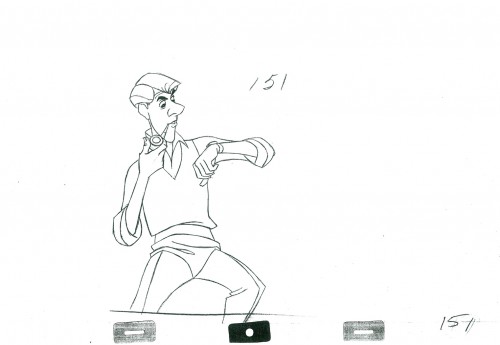

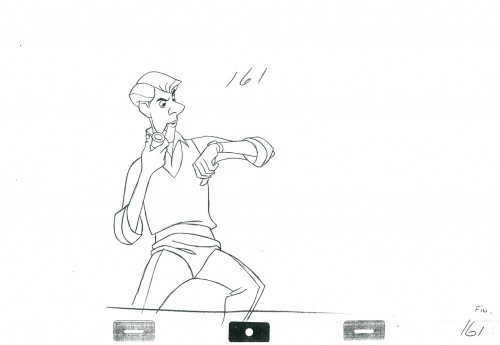

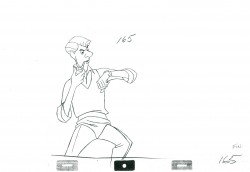

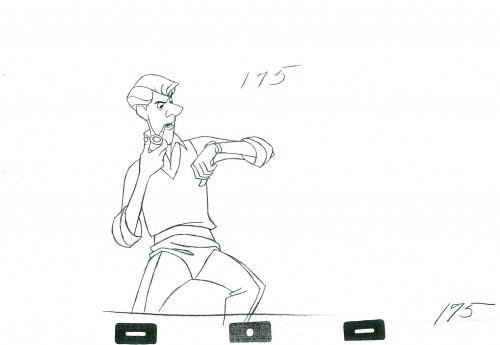

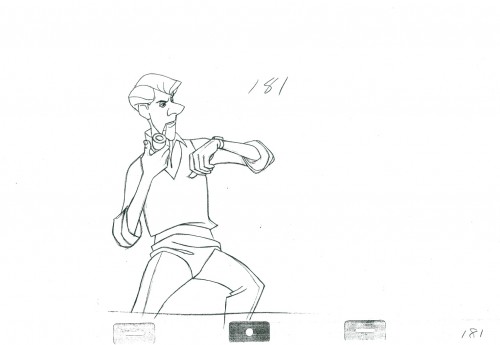

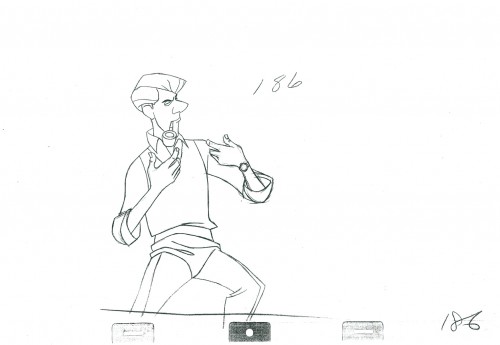

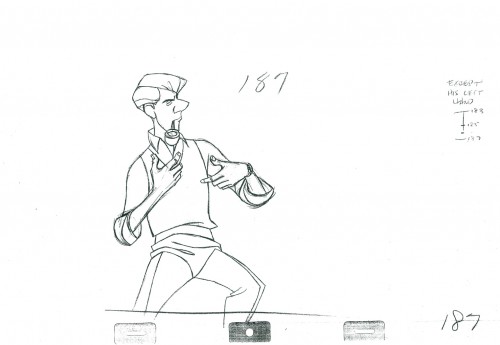

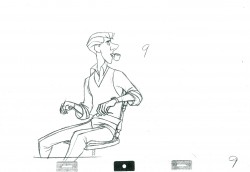

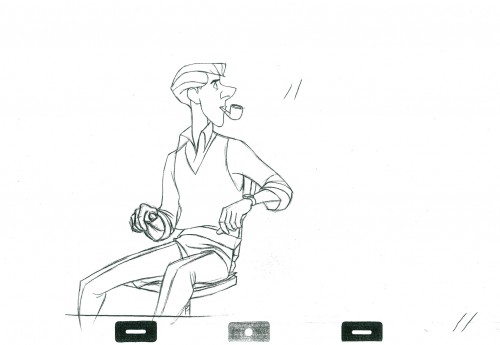

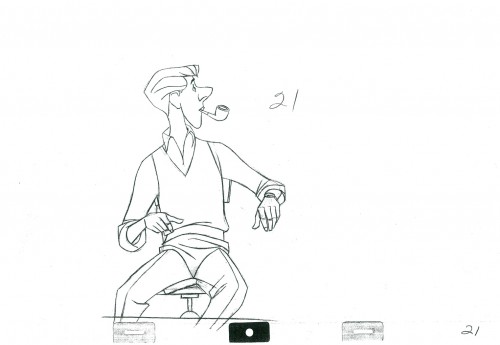

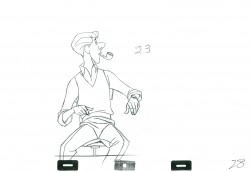

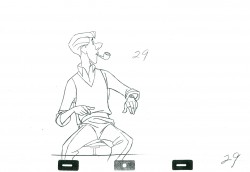

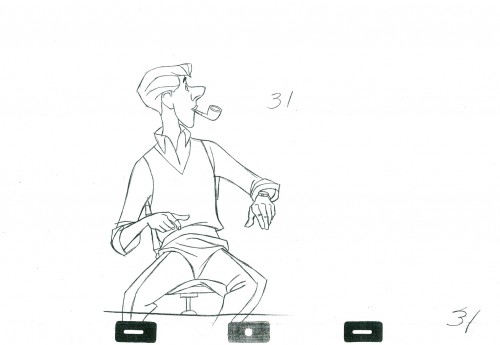

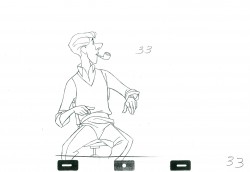

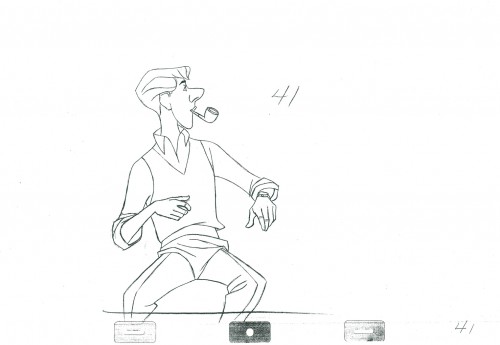

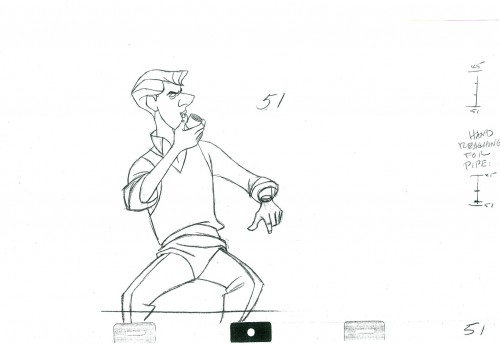

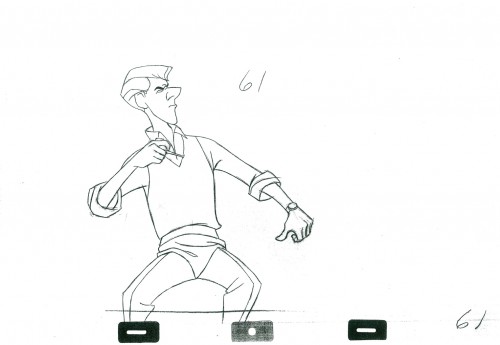

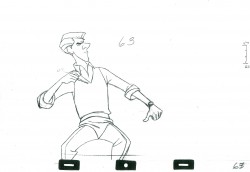

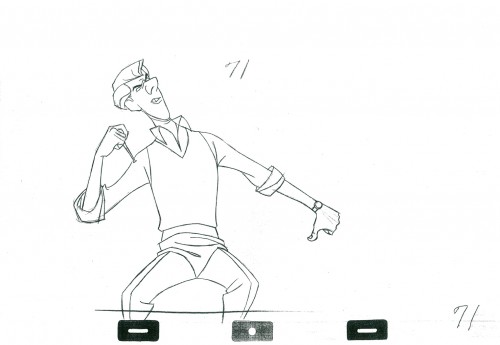

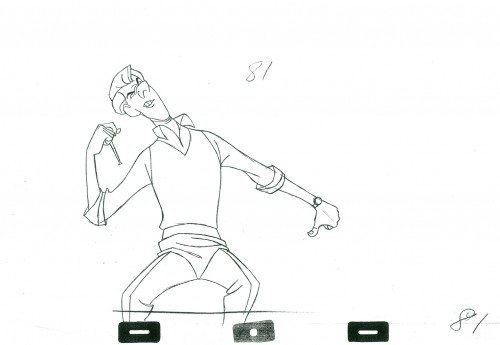

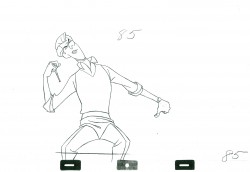

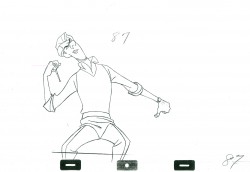

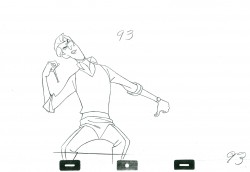

Learn about your business, but also learn about the world. That’s the only way you can relate to how your character should think and emote. All of the Disney drawings on this site and other ones really won’t help you figure out YOUR character’s development. Only you can do that.