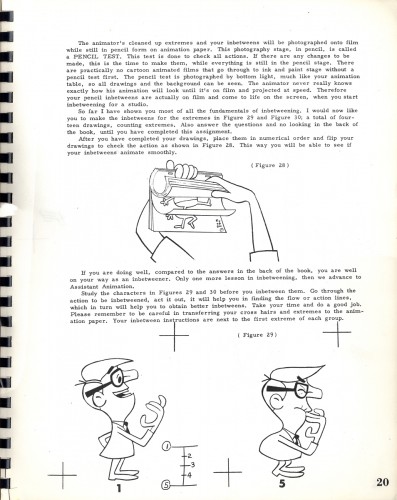

Action Analysis &Animation &Books &Commentary 06 Dec 2012 07:03 am

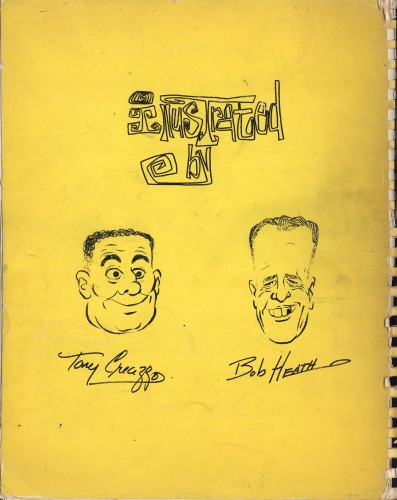

The McKimson Brothers

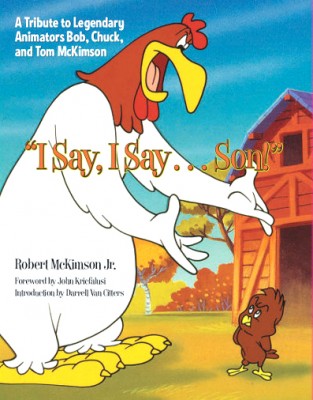

I Say, I Say . . . Son! This is the title of a book by Robert McKimson Jr. Any ideas what it might be about?

I Say, I Say . . . Son! This is the title of a book by Robert McKimson Jr. Any ideas what it might be about?

Sound anything like Foghorn Leghorn?

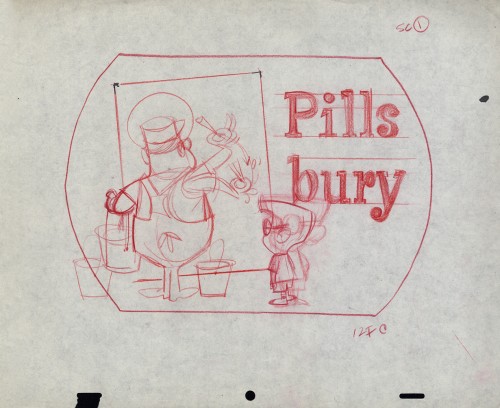

Yes, it’s a tribute to Bob McKimson with a big nod to Chuck and Tom McKimson, as well. This, to me, is something of a feat in its own right. The book is a workhorse of a picture book with lots of valuable images that you haven’t seen before. It’s not like the big glamour picture books that come out of Disney or Dreamworks. The Art of Whatever. It’s not one of those heavyweight oversized books that cause coffee table legs to bowl outward under their weight. No, this is a go to book on good paper; it’s solid. There are lots of drawings and photographs, frame grabs, newspaper clippings, and posters. Just looking at the pictures will give you a pretty good idea of the story the book is telling.

And it’s a valuable story – the part of the jigsaw puzzle that’s been left missing.

There have been about a half dozen books by and about Chuck Jones, one enormously expensive tome on Friz Freleng with lots of key references to him in most animation histories. Bob Clampett did a lot to promote himself; he gave us films and videos, not books. There are at least three Tex Avery books. This is the first on Robert McKimson – the other Warner’s director. And it was written by his son.

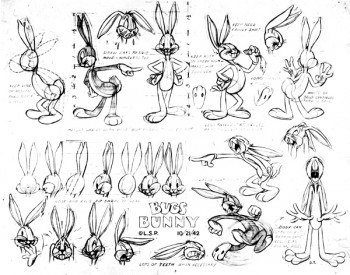

McKimson was loved by Leon Schlesinger who tried to make him a director early on. Yet, Bob didn’t feel that he was ready. He became the head of all animators in the studio, responsible for solidifying the style of all the different variations of the characters. He helped tie Jones’ Bugs Bunny to Freleng’s or Clampett’s Porky Pig to Tashlin’s. When Schlesinger sold the studio in 1944 and Eddie Selzer took charge, McKimson pushed himself into the directorial position, and he gave us meat and potatoes films with characters that were all his: Foghorn Leghorn, the Tasmanian Devil, Sylvester Jr., and some of the Speedy Gonzales work.

Before reading this book I was certainly well aware of Bob McKimson‘s work, and I was not quite as familiar with the other McKimson brothers. I’m not sure much has changed about that. As an animator Bob McKimson was brilliant, but as a director I never quite saw the lyricism that we saw in some of his best animation. McKimson was the Milt Kahl of the WB studios. He could draw like dynamite and knew every trick in the

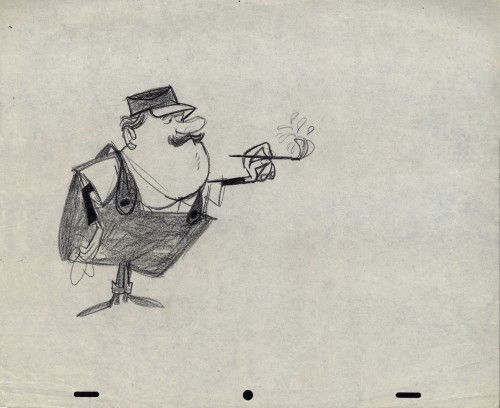

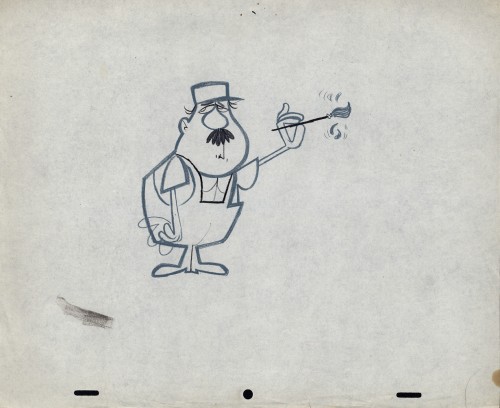

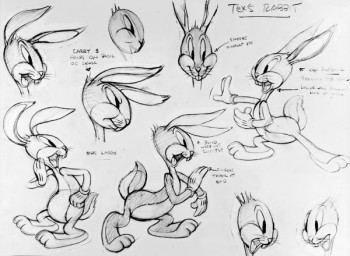

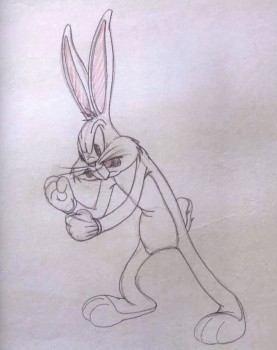

Before reading this book I was certainly well aware of Bob McKimson‘s work, and I was not quite as familiar with the other McKimson brothers. I’m not sure much has changed about that. As an animator Bob McKimson was brilliant, but as a director I never quite saw the lyricism that we saw in some of his best animation. McKimson was the Milt Kahl of the WB studios. He could draw like dynamite and knew every trick in the  service of giving the tightest, sharpest animation possible. When you look at his scenes you’ll see beautifully drawn animation with solid timing and a muscular approach. Go to an extreme and take the pose as far as you can, and then go farther still, and then go even farther still. Bob not only did that, but his brilliant draftsmanship held the characters together in those unrelenting poses. It was near miraculous how _____2 of many Bugs model sheets drawn by Bob McKimson

service of giving the tightest, sharpest animation possible. When you look at his scenes you’ll see beautifully drawn animation with solid timing and a muscular approach. Go to an extreme and take the pose as far as you can, and then go farther still, and then go even farther still. Bob not only did that, but his brilliant draftsmanship held the characters together in those unrelenting poses. It was near miraculous how _____2 of many Bugs model sheets drawn by Bob McKimson

he pulled that off. Animators

like Rod Scribner or Jim Tyer would go as far as he did, but their drawings blew up into funny. Bob’s artwork just got more solid. Bobe Cannon was probably the only other person at WB that could match him for drawing ability. Even still Cannon would purposefully distort his drawings more than McKimson would. Bobe was interested in the 20th Century Art, Bob was interested in the artistry.

As may be obvious, I’m not the greatest enthusiast when it comes to Bob’s direction. It all shows so little panache that I must say I’ve easily dismissed it. The work is just that, a solid bit of work. The backgrounds are cartoon realistic. No flair the way you’d find in Maurice Noble‘s art, no personality as in Paul Julian‘s paintings. Dick Thomas, Cornett Wood and Robert Gribbroek did most of the design and background painting. All of the effort was put into the animation and little concentration seemed to focus on the design of the films. I can remember Mike Barrier talking about McKimson’s work. His layouts and the stacks of animation drawings that came from his cartoons far outweighed the piles of art from work by the other directors. Jones’ impeccable poses, Freleng’s exquisite timing. McKimson worked the funny into his cartoons and he got the same from his animators. He used drawings and more drawings. The style came from good, hard solid work, not timing or poetry.

As may be obvious, I’m not the greatest enthusiast when it comes to Bob’s direction. It all shows so little panache that I must say I’ve easily dismissed it. The work is just that, a solid bit of work. The backgrounds are cartoon realistic. No flair the way you’d find in Maurice Noble‘s art, no personality as in Paul Julian‘s paintings. Dick Thomas, Cornett Wood and Robert Gribbroek did most of the design and background painting. All of the effort was put into the animation and little concentration seemed to focus on the design of the films. I can remember Mike Barrier talking about McKimson’s work. His layouts and the stacks of animation drawings that came from his cartoons far outweighed the piles of art from work by the other directors. Jones’ impeccable poses, Freleng’s exquisite timing. McKimson worked the funny into his cartoons and he got the same from his animators. He used drawings and more drawings. The style came from good, hard solid work, not timing or poetry.

There are all those stories about Rod Scribner and his wildly artistic period under Clampett. He was a different guy under McKimson. It’s hard to see the same animator in the two different phases. There’s pure delight in the animation under Clampett and solid workmanlike craft under McKimson. No doubt this was also because Clampett probably was off leaving Scribner on his own to do what he wanted. McKimson kept Scribner under his thumb and, in my opinion, didn’t get that great and wild personality that had been available. As a matter of fact, I suspect this was true of all the artists McKimson controlled. It probably worked well with the two brothers, Chuck working under Bob’s direction, but I’m not convinced it was the best way for most artists to work.

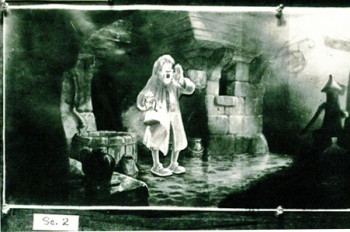

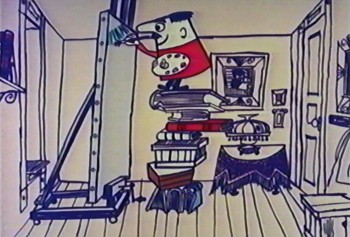

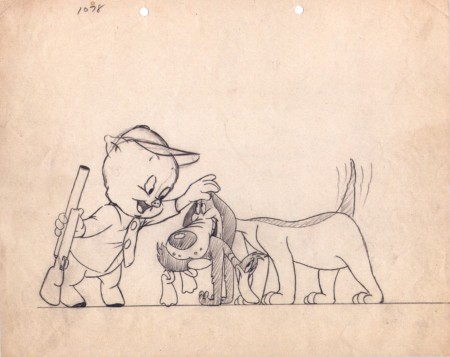

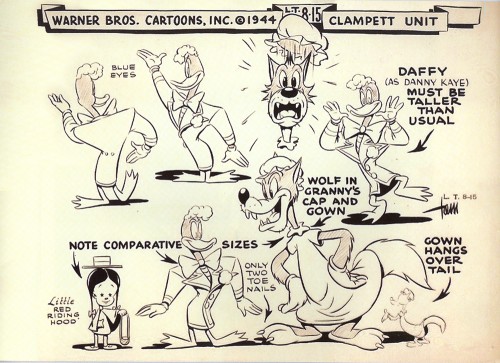

A Bob McKimson Layout for “daffy Duck Hunt” (1949)

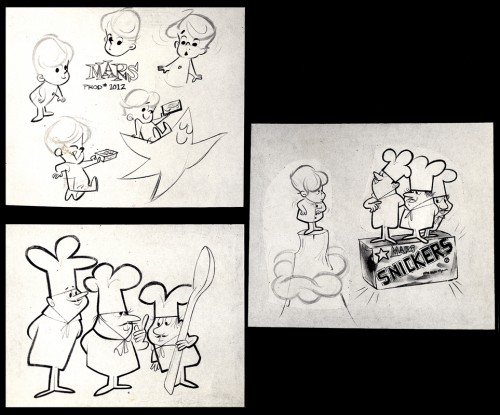

For this book, there can be no doubt that a major source of information had to have been Mike Barrier‘s excellent interview with McKimson. (Go here if you want to read that – and you should have already read it.***) I’m afraid there is no interview with Tom or Chuck McKimson readily available. I would have liked to see more of them in this book. Toward the end of the book, we see roughs and stills from the illustration work the two have done for comics and coloring books. Robert McKimson certainly dominates the bulk of this volume.

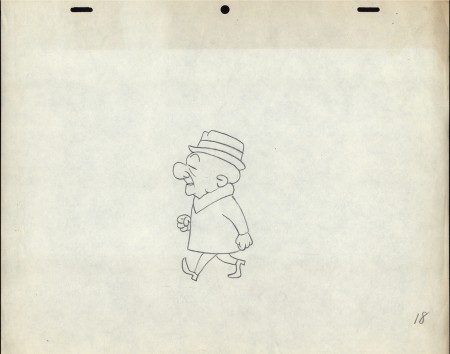

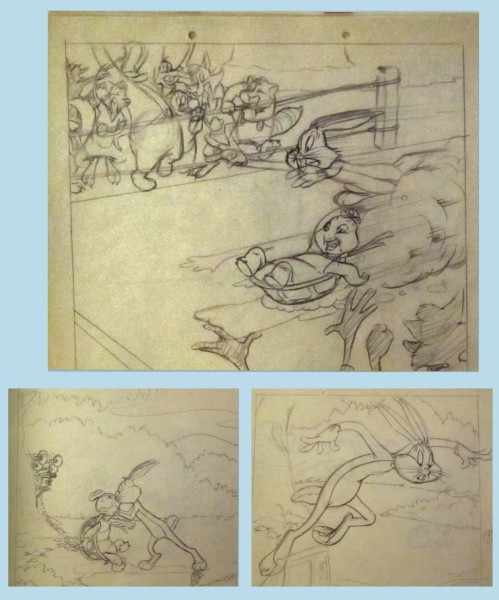

It is the visual materials available here that shows the real value of the book and makes it important to own. For anyone who recognizes the importance of WB cartoons and wants the whole picture recognized this is the reason for this book. The artwork. There are some beautiful early drawings printed, especially, the pages of clean-roughs done by Bob that were animated by Tom. Excellent poses once again from Bob with no sign of Chuck’s drawing. Again, it’s only toward the end, when we get into the comic books and other print material, that we see some of Chuck and Tom’s artwork. These are definitely not up to that of Bob’s drawing, but if the focus is to be on all three, we need to see all three on display.

I appreciated the photos throughout as well as a reprint of the few articles about any and all of the brothers. Perhaps more of an analsis from the author about the variance from one artist to another. Despite their being brothers, they do have very different talents and we can see, despite the limited amount of art from Tom & Chuck, that Bob was the obviously the strongest draftsman of the three, but there for the lack of drawings goes this book.

Regardless, I’m glad to have what I do have. The excellent WB art of Bob McKimson and the familiar comic book covers of Tom. Both broght back memories of differing kinds. Chuck, he was the animator, he worked within his brother’s unit at WB, and there isn’t much sign of his drawing. But the films are there, and we can enjoy those films and the talent that went onto their making. I wonder if ever there were a conversation or a statement by Bob about his brothers’ work. Perhaps someday, that curtain will be opened a bit more. Until then, I’m grateful for this book.

*** Actually if you want to go the heart of animation history just go through Mike Barrier‘s archives and interviews, and you’ll have a good solid base. Take a tour of MichaelBarrier.com. Spend a lot of time there.} Perhaps someday we’ll get Mike Barrier’s article about the three brothers. Maybe a review of this book will bring him out on the subject.

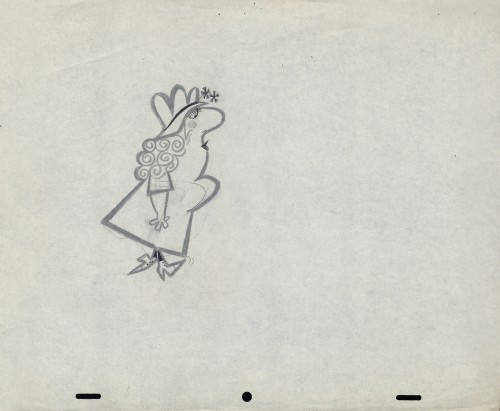

Bugs Bunny and the Tortoise

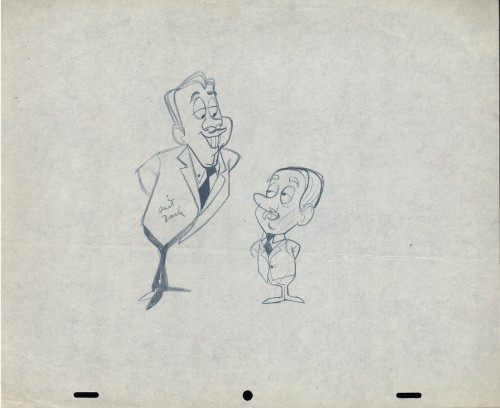

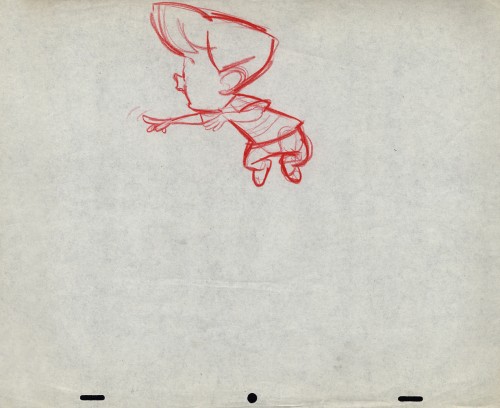

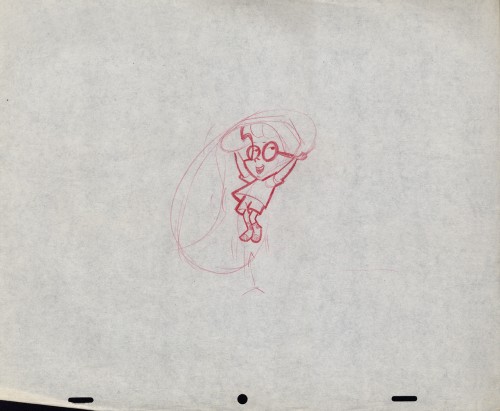

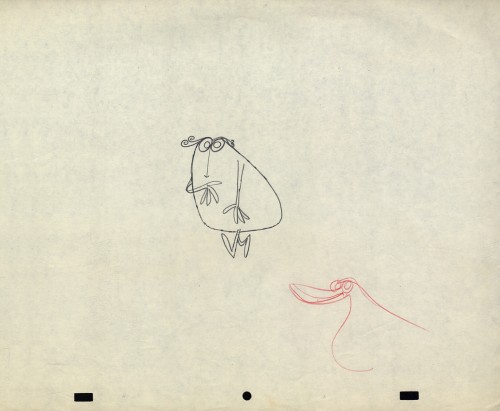

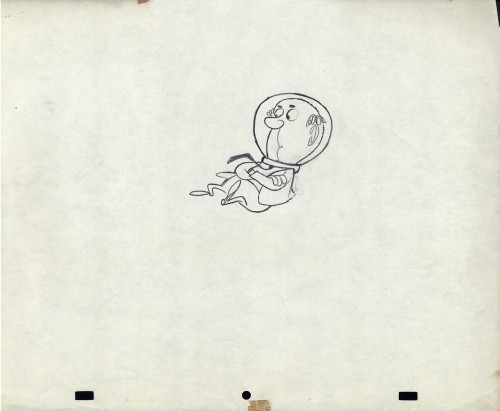

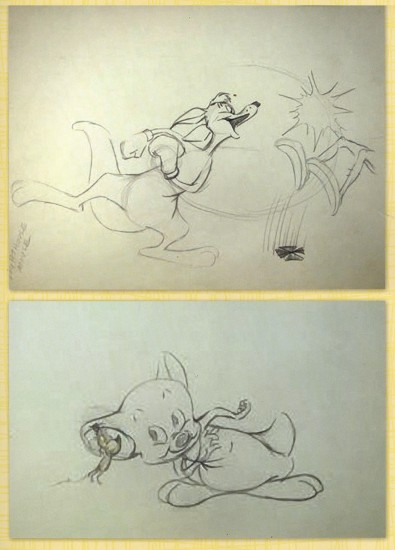

Some roughs for a 1948 book by Bob McKimson.

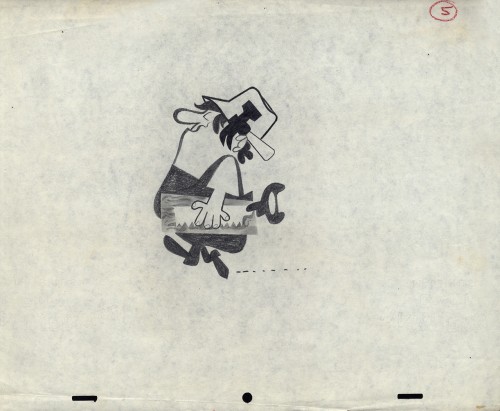

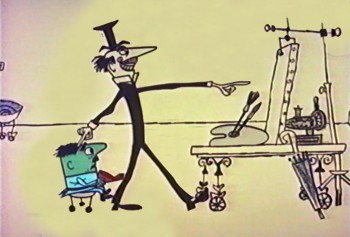

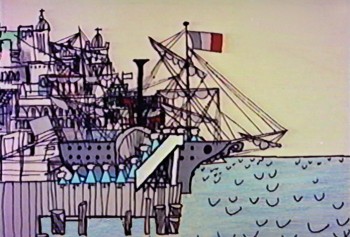

Top – Layout for “Hippity Hopper” (1949) Bob McKimson

Bot – Layout for “Lighthouse Mouse” (1955) Bob McKimson

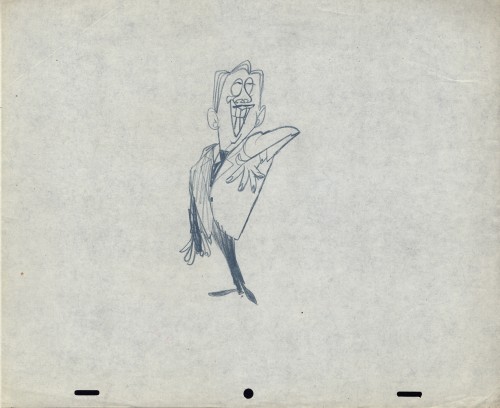

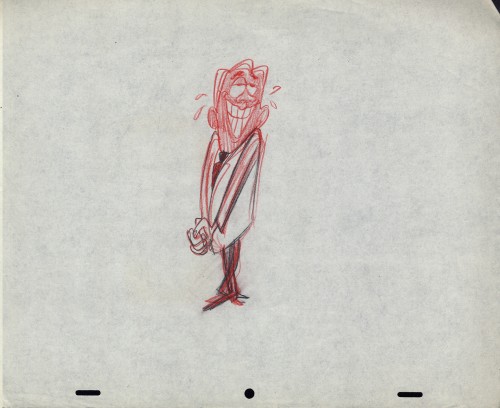

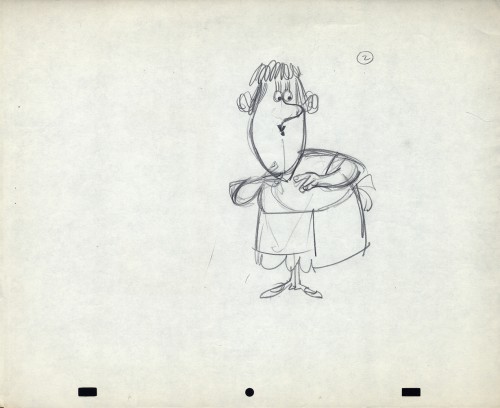

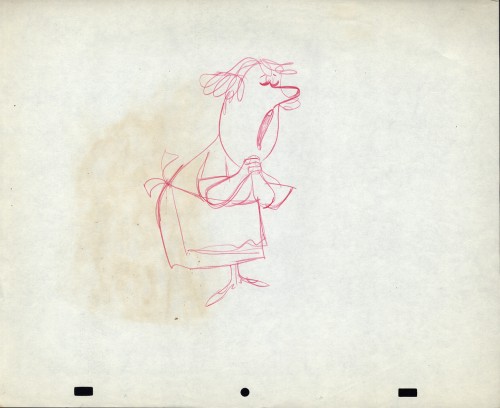

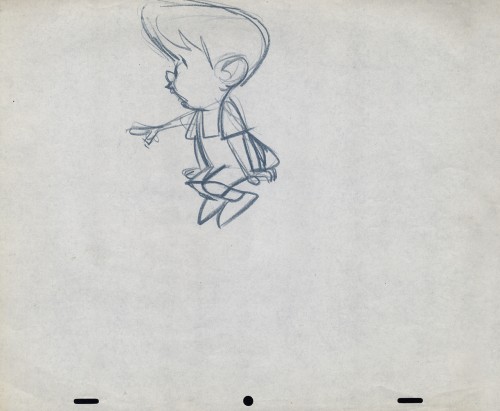

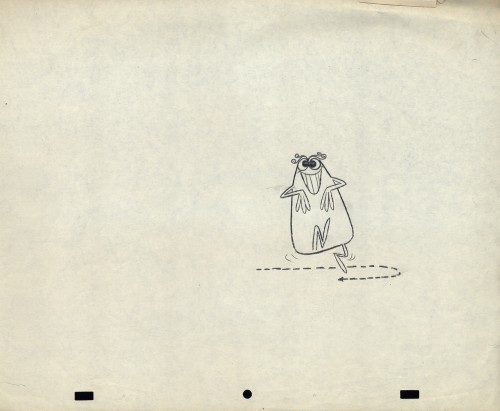

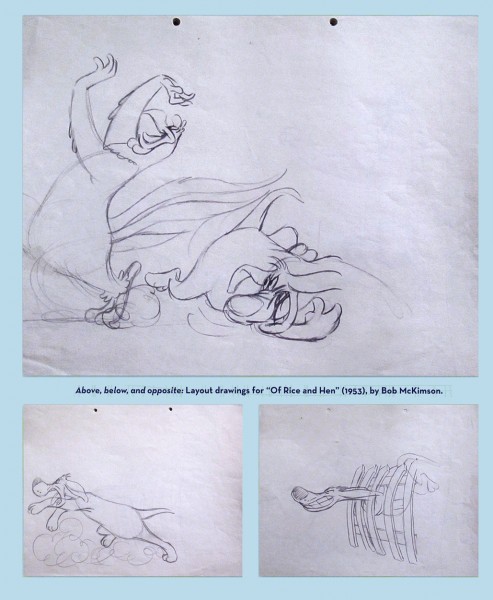

Some beautiful roughs for Layouts by Bob McKimson

for “Of Rice and Hen” (1953) directed by him.

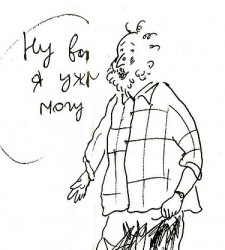

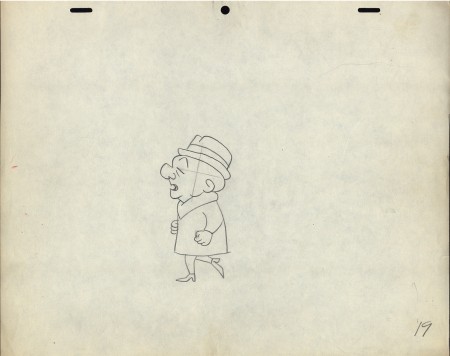

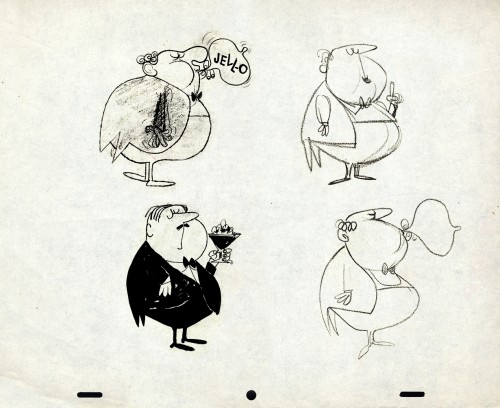

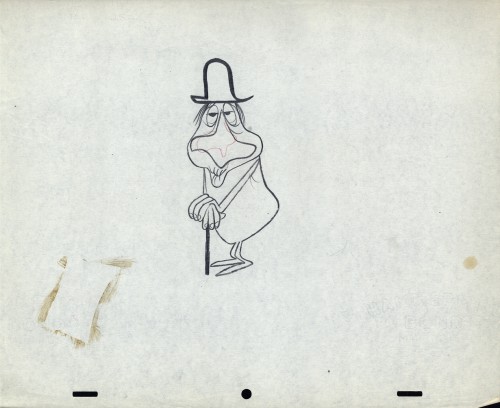

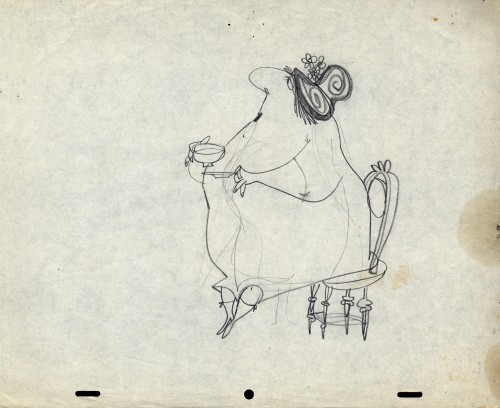

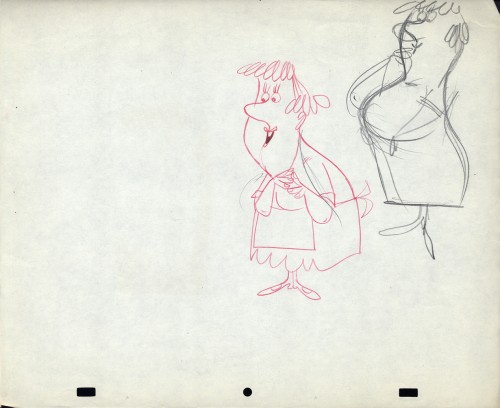

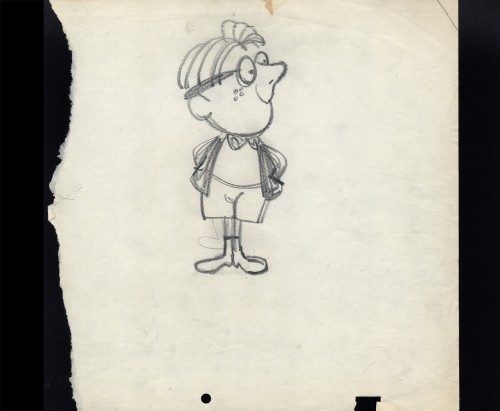

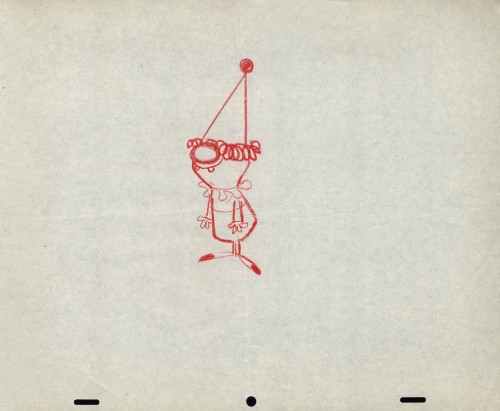

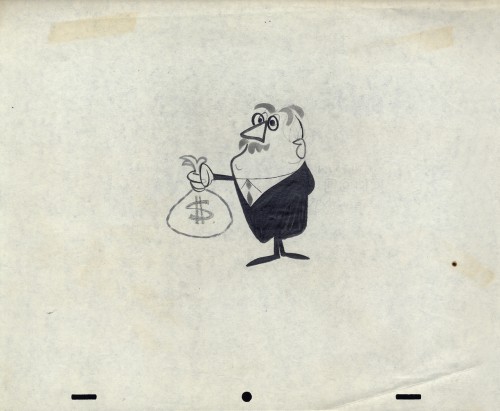

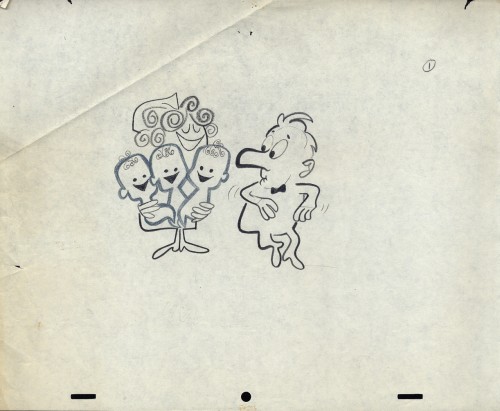

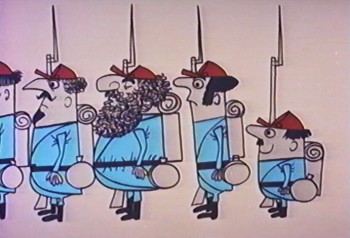

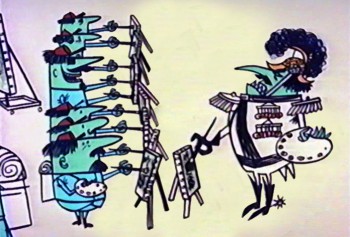

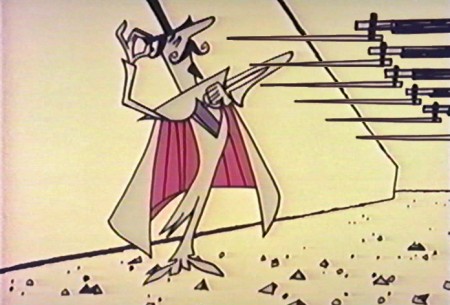

A model sheet by Tom McKimson. One of a few in the book.

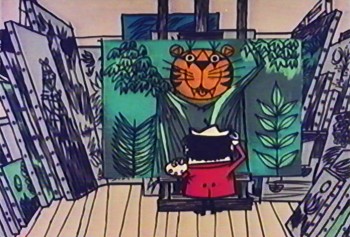

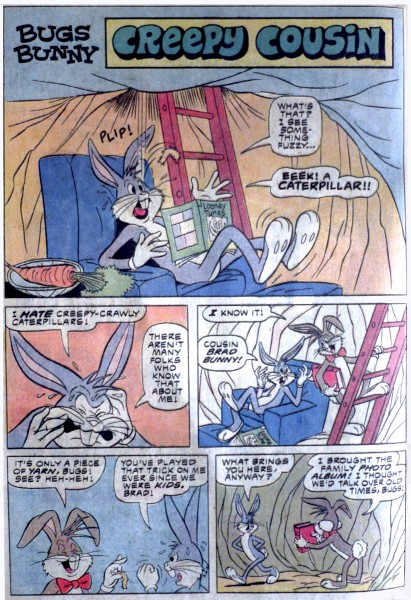

A comic book page by Tom McKimson

A very different model than Bob would have drawn.

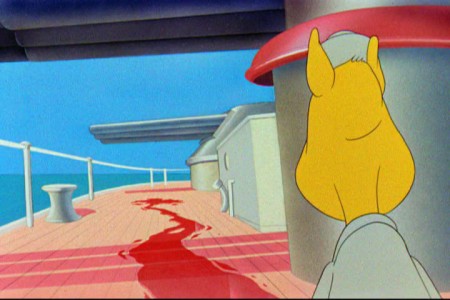

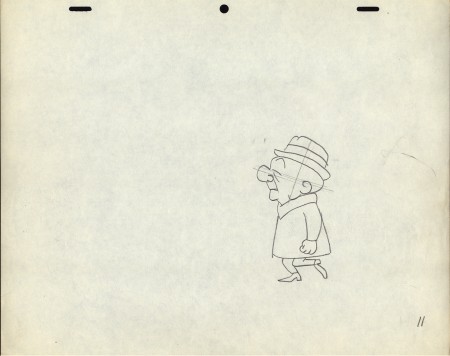

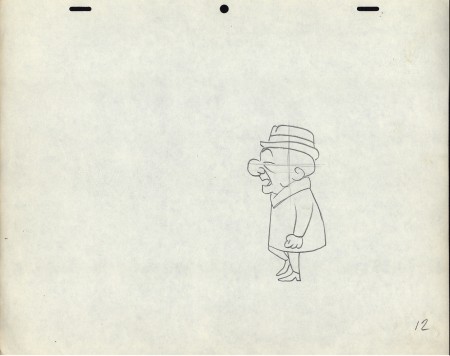

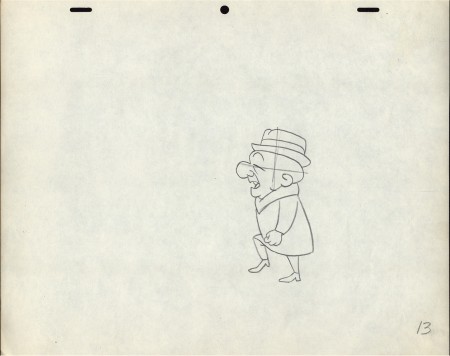

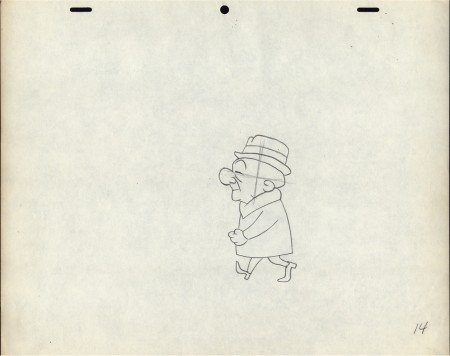

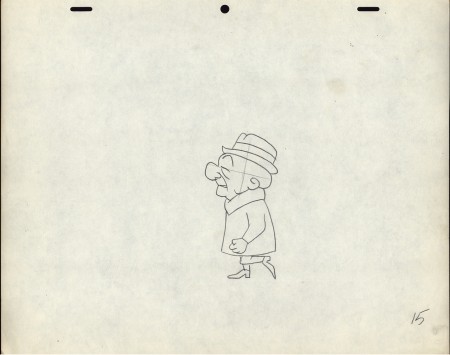

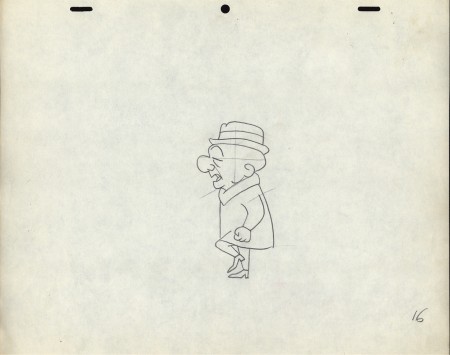

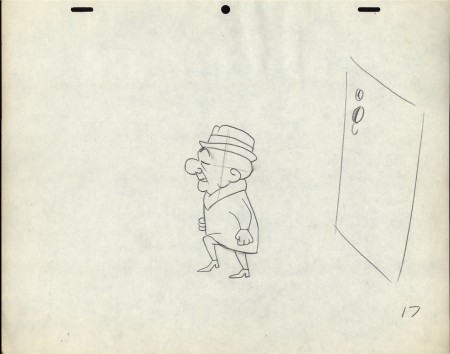

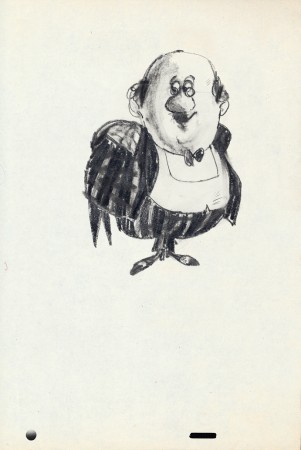

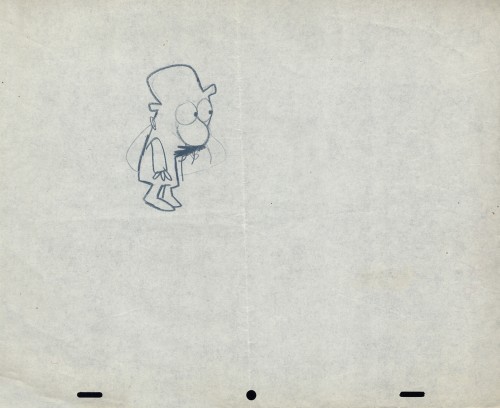

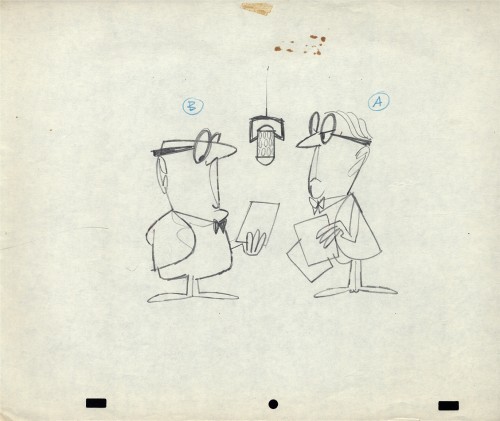

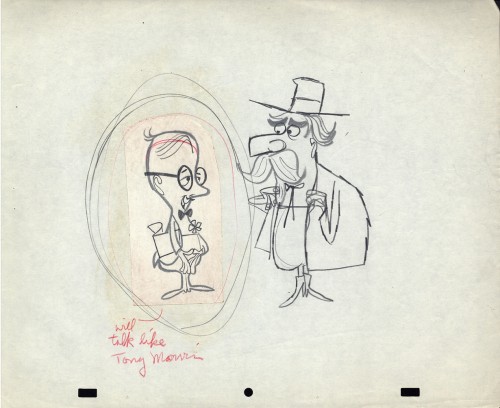

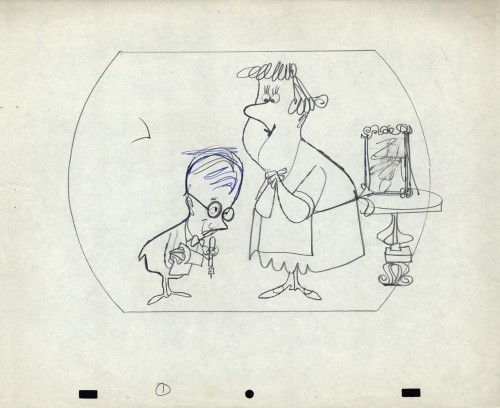

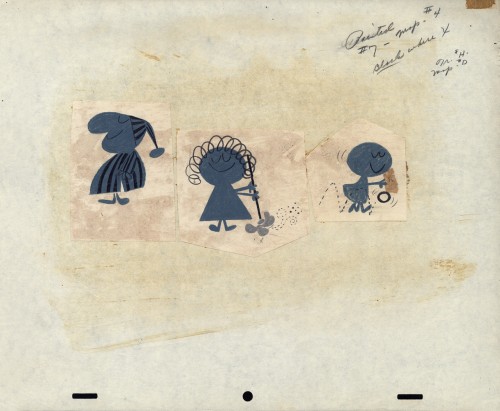

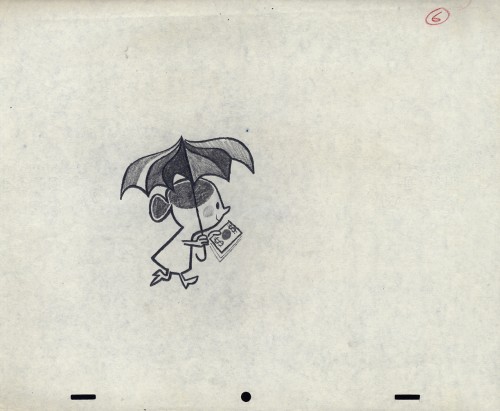

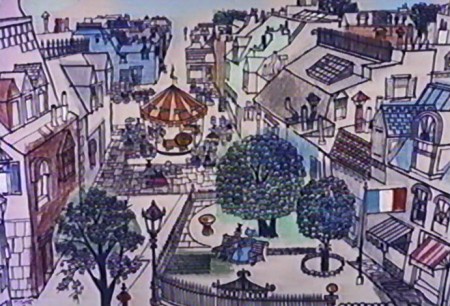

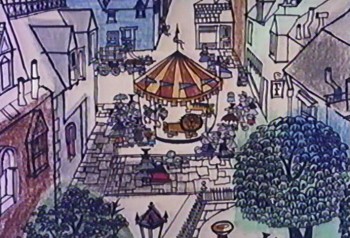

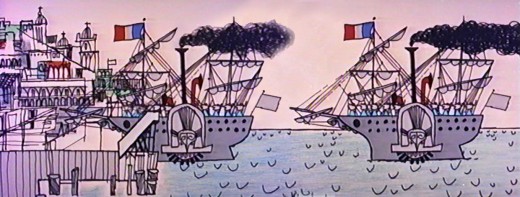

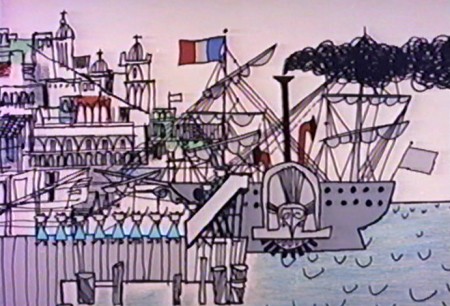

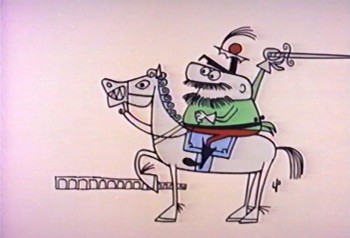

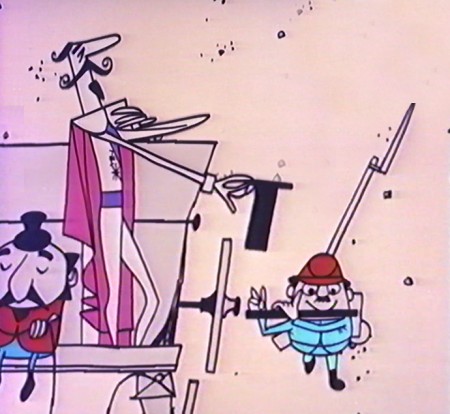

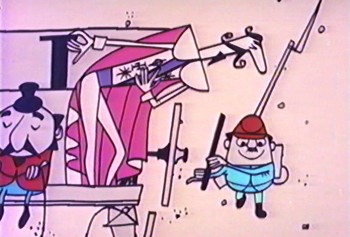

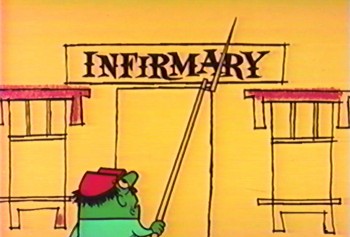

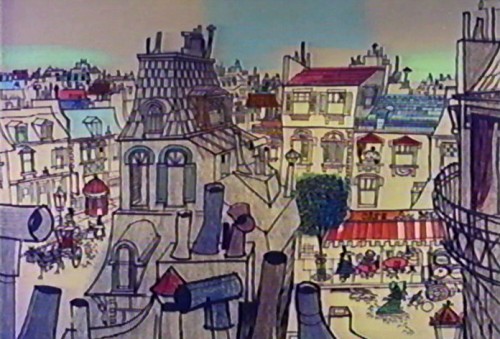

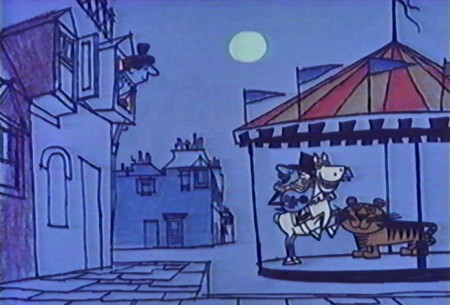

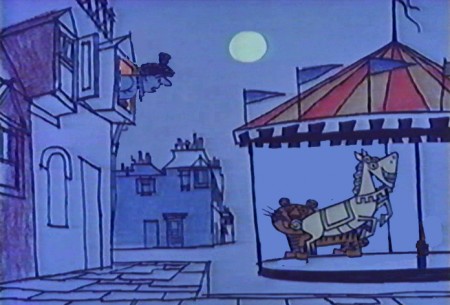

A setup from “Calvin and the Colonel” directed by Chuck McKimson (1962)