Animation &Commentary &Daily post &Errol Le Cain &Richard Williams 25 Feb 2013 05:28 am

POV

Next Friday, at the invitation of filmmaker-editor-director, Kevin Schreck, I’ll have the pleasure of seeing his recently completed documentary, Persistence of Vision. This is the story of the making of Richard Williams‘ many-years-in-the -making animated feature, The Cobbler and the Thief. I’m not sure of the film maker’s POV, but I somehow expect it to be wholly supportive of the insistent vision of Richard Williams in the making of this Escher-like version of an animated feature. A work of obsession.

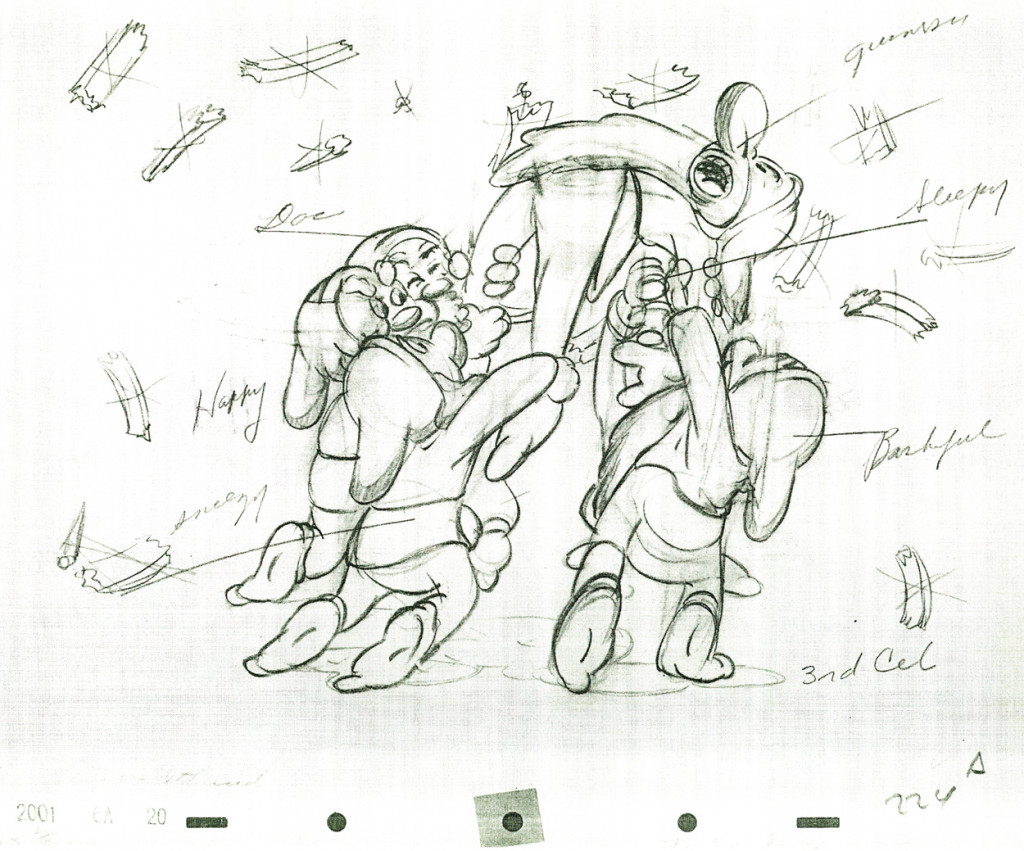

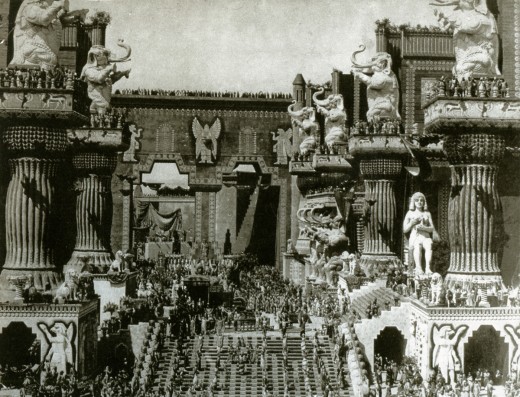

It’s the tale of an “artist”, someone who sees himself as an artist, and continually pushes through the world with what would seem to be evident proof of such. After all, this man had single-handedly altered the face of 2D animation in a world that was about to throw it away with all its rich history and artistry and strengths. A medium that had developed through the years of Disney with giant, filmed classics such as Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia and even Sleeping Beauty. A medium that had drastically changed to 20th century graphics under the hands of people like John Hubley, Chuck Jones, George Dunning and many others and had just about reached a zenith where it was moving toward something wholly new, something adult.

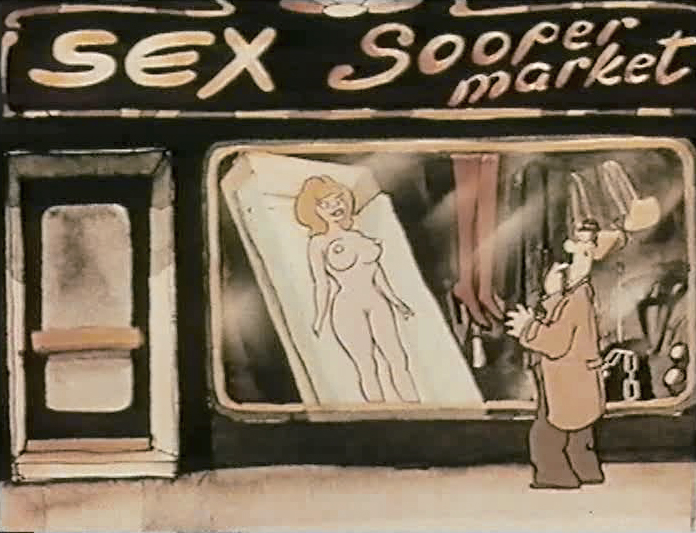

Instead the medium took a turn in the wrong direction. The economics of television brought us back almost 100 years as films became more and more simplistic and simpleminded in the rush to be cheap. Even the Disney studio went for the poorest subject matter using cost-saving devices to sell their films. Films became shoddier and shoddier, and the economics ruled. The closest the medium would come to art was Ralph Bakshi‘s Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic, low budget movies that traded on racy material in exchange for an attempt at something adult, stories barely held together with editing tape. Animation was getting a bad name from every corner whether it was the sped-up graphics of Hanna-Barbera, the reach to the lowest common denominator with poor animation from Disney, or the shock and tell of Ralph Bakshi‘s filmed attempts at what he saw as art.

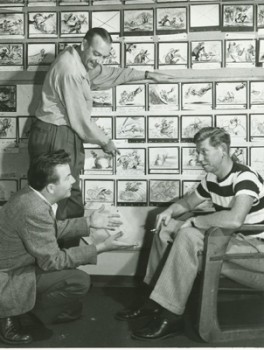

Williams took a different turn. He went back to the height of animation’s golden era, inviting artists such as Grim Natwick, John Hubley, Ken Harris and Art Babbitt to his London studio to lecture on the rules and backbone of the animation. He brought some of these people to work on a feature that he’d decided to create within his studio on the profits of commercials. These very same commercials financed the training of Dick and his young staff.

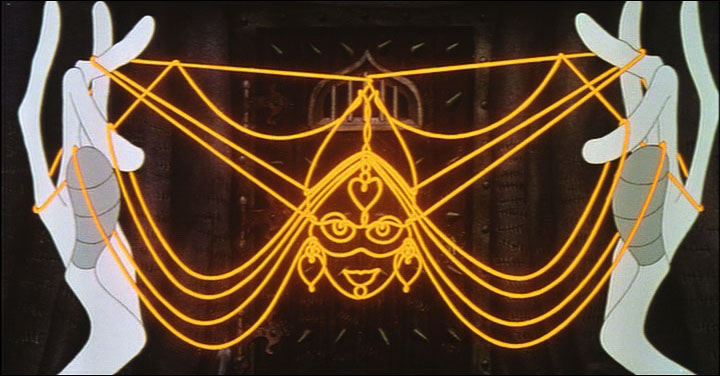

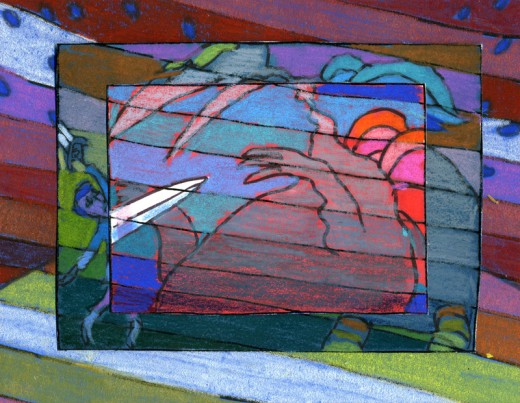

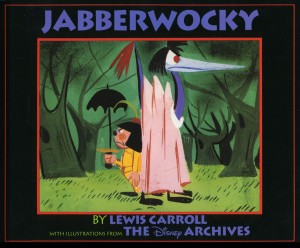

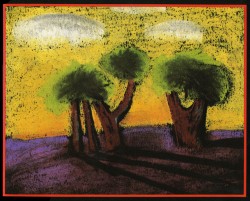

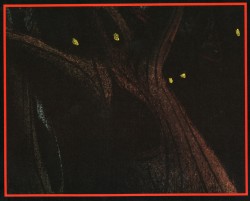

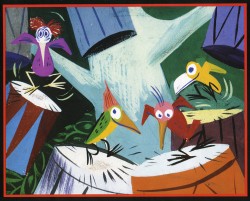

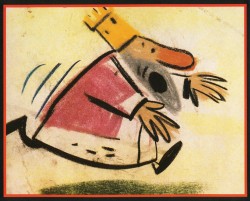

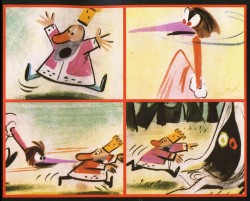

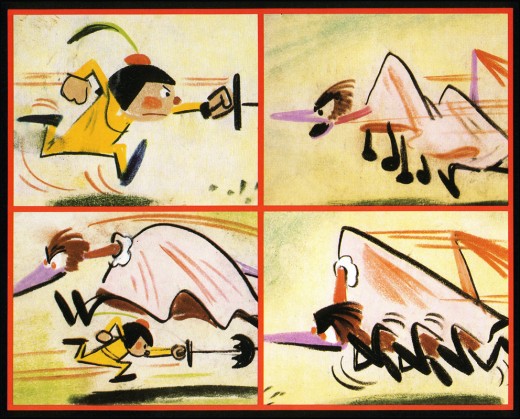

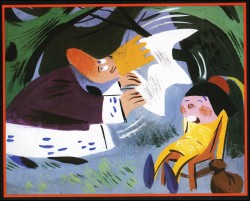

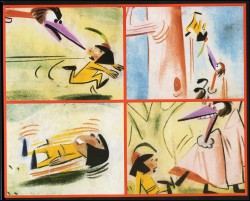

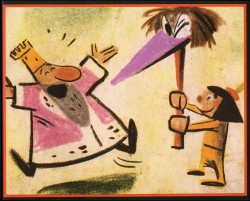

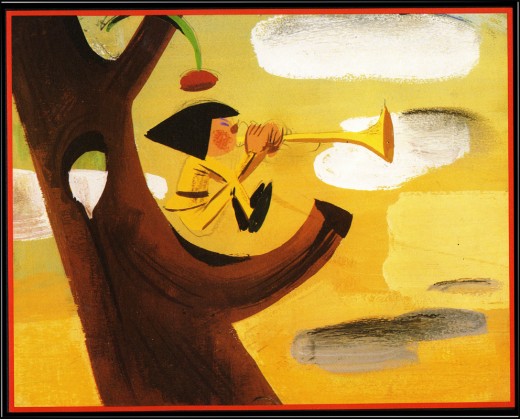

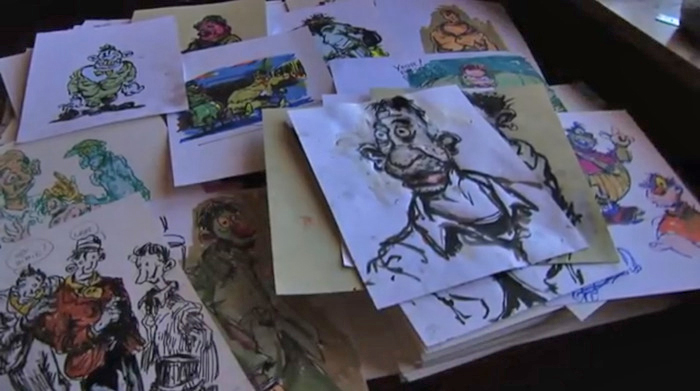

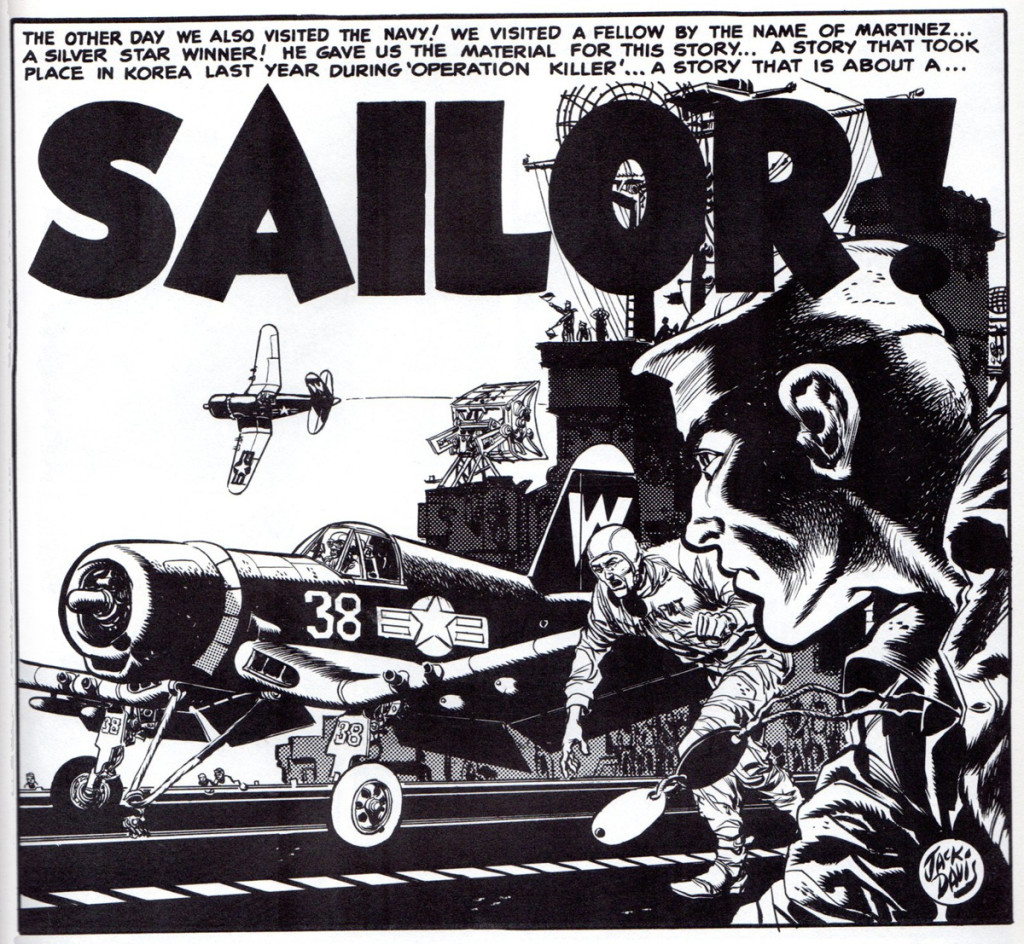

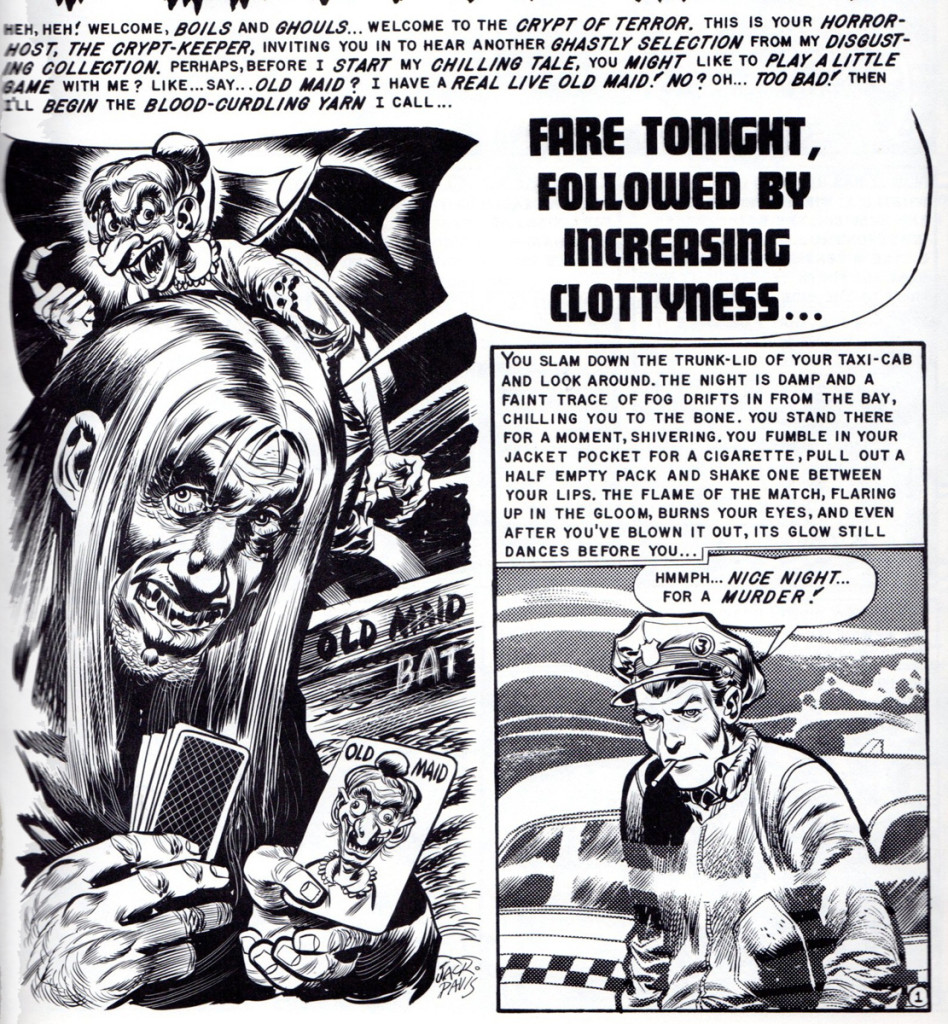

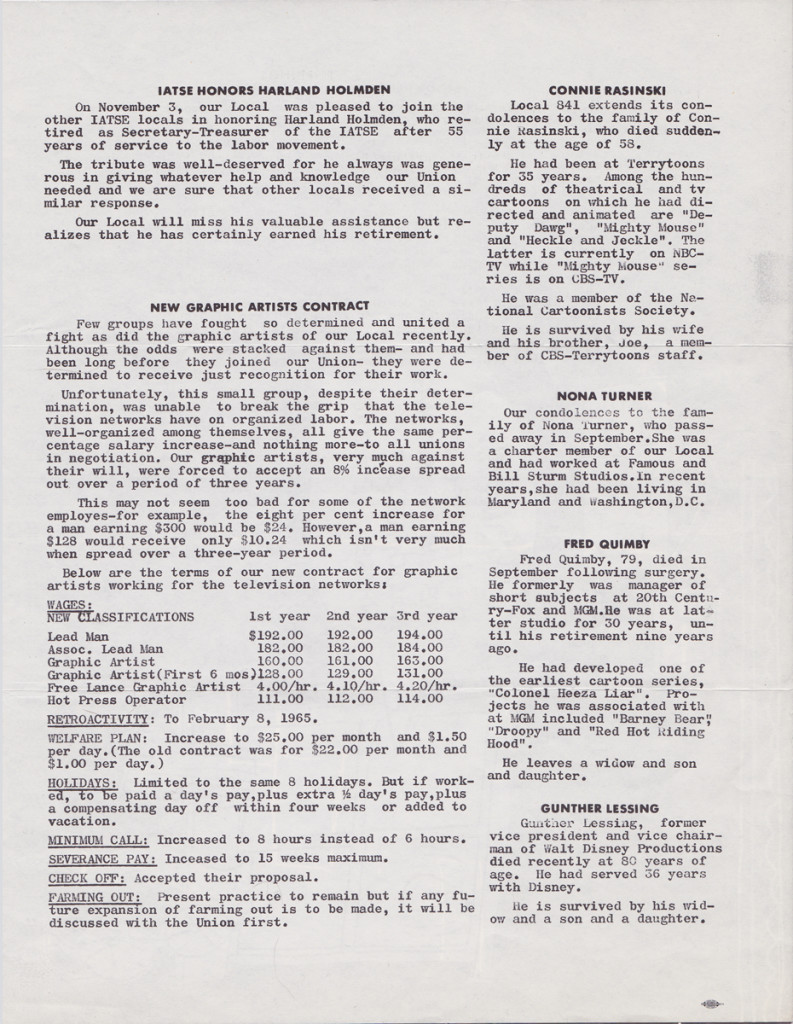

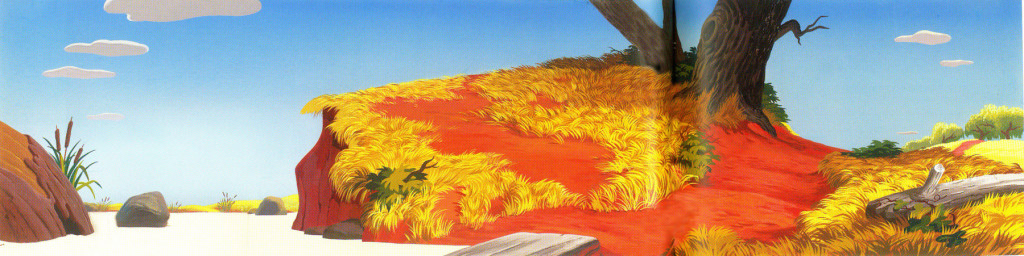

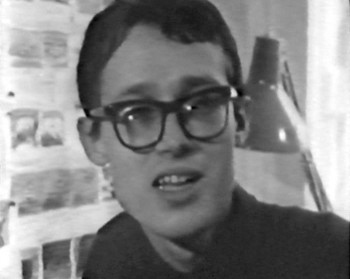

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

A documentary done in 1966, called The Creative Person: Richard Williams offers an excellent view of his studio. We see snippets of shorts Dick made with his own coin: Love Me Love Me Love Me (1962) or The Sailor and the Devil (1967) wherein we see the training of a young and brilliant illustrator named Errol le Cain. (Le Cain became known for his magnificent, glimmering children’s book illustrations. He was doing most of the backgrounds for The Cobbler and the Thief, and had certainly had a large part in its design.)

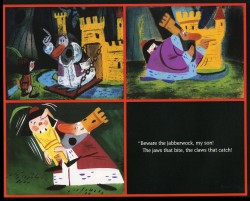

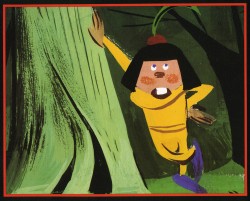

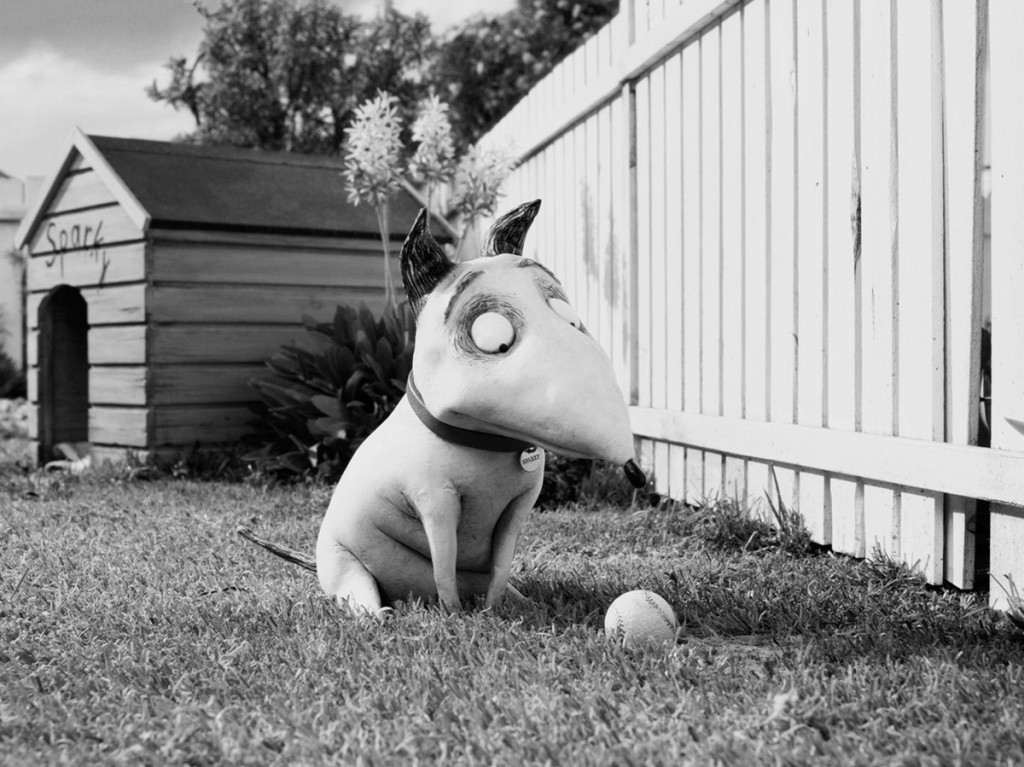

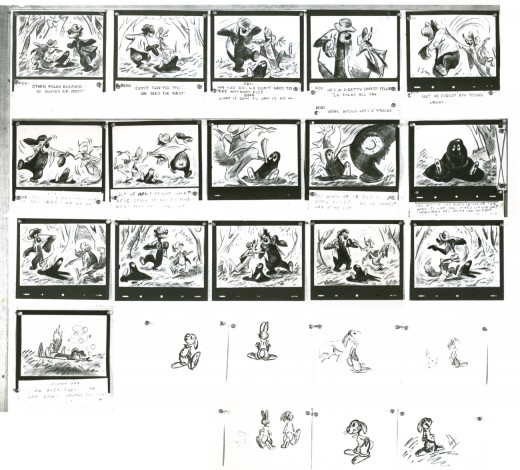

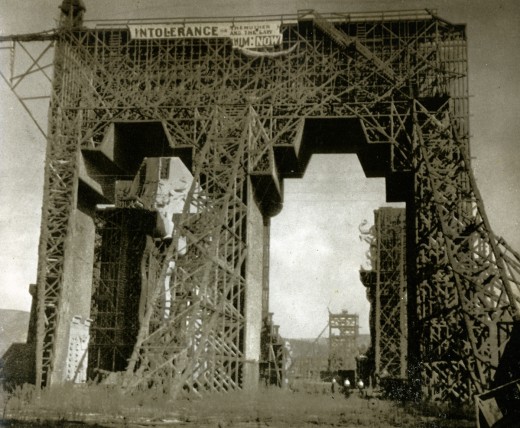

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

We see in this documentary the first hint of The Cobbler when it was called Nasruddin. It was based on a book of middle eastern tales of a wise fool whose every short story tells a new and positive anecdote. Dick had illustrated several books of these tales with many funny line drawings. The book was written by the Idres Shah who had undertaken a role within the Willams studio finding funds for the feature. Eventually, the two had a falling out, and Idres Shah left with his property. Williams took the work he had done as Nasruddin and reworked it into The Cobbler and the Thief. ________________________________Errol le Cain

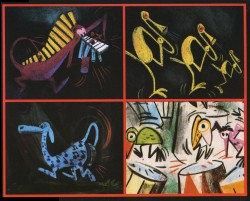

Meanwhile the work within his studio continued to develop, growing more and more mature. The commercials became the highlight of the world’s animation. Doing many feature film titles such as What’s New Pussycat (1965), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) led to Dick’s directing a half-hour adaptation of The Christmas Carol (1971). Chuck Jones produced the ABC program, and it led to an Oscar as Best Animated Short.

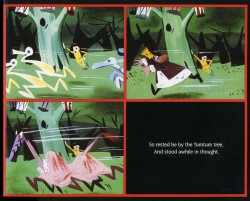

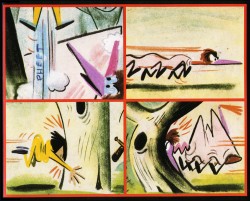

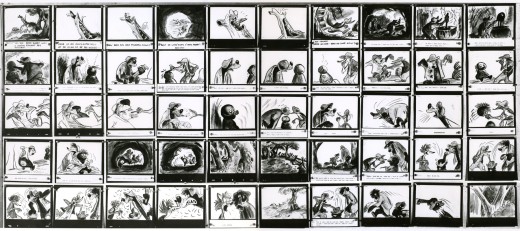

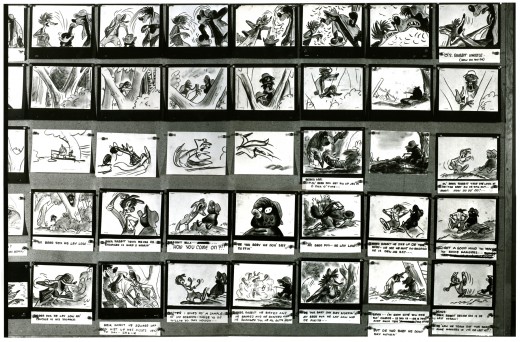

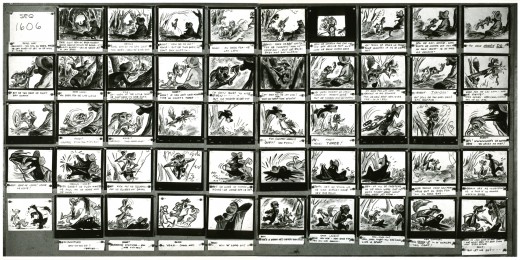

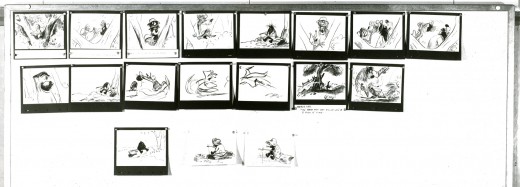

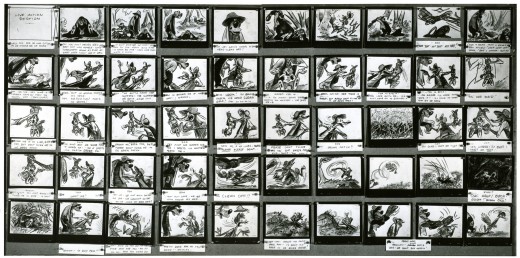

Through all this The Cobbler and the Thief continued. Many screenplays changed the story and the stunning graphics that were being produced for that film were often shifted about to accommodate the new story.

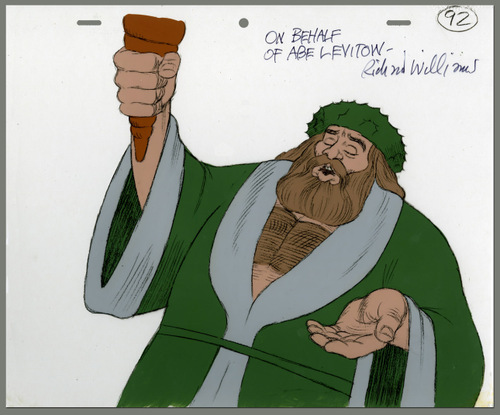

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

By this time, Williams had developed something of a name within the world of animation. Strong and important animation figures went to his studio to work for periods of time. Someone like Abe Levitow taught and animated for the studio. (His scenes for The Christmas Carol are among the most powerful.) Many of the Brits that worked in the studio and then left to start their own companies were now among the world’s best animators.

Williams had the opportunity of doing a theatrical feature adaptation of the children’s books The Adventures of Raggedy Ann and Andy and took it. A large staff of classically trained animation leaders such as Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, Tissa David, Hal Ambro, Emery Hawkins and many others worked out of New York or LA as the company set up two studios to produce this film. Working for over two years, Dick’s attention was diverted to work away from his London studio, where commercials and some small devotion was given to The Thief by a few of the key personnel working there. Dick spent a good amount of his time in the air flying from NY to LA to NY to London and back again and again. He concentrated his animation efforts on cleaning up animation by some of the masters, rather than allow proper assistants to do these tasks. By doing this he was able to reanimate some of the work he didn’t wholly approve of. Entire song numbers were reworked by Dick as the film flew well behind its budget and schedule.

Eventually, the film finished in confusion and mismanagement, and Dick moved to his LA studio where he continued commercials and began Ziggy’s Gift, a Christmas Special for ABC.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

From this he went back to his London studio and did the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit for producer/director Robert Zemeckis. He hoped that work on this feature, which won three Academy Awards, including a special one for the animation, would be the triumph he needed to help him raise the funds for The Thief and the Cobbler. Now that he was safely back in his own studio in Soho Square he felt more focused.

A contract came from Warner Bros., and the work began in earnest.

Dick’s history wasn’t the best working on these long form films. Chuck Jones replaced him on The Christmas Carol to get it finished when work went overbudget and schedule. Dick was putting too much into it. Gerry Potterton finished Raggedy Ann when the budget went millions over with less than a third completed. Eric Goldberg took over Ziggy’s Gift, the Christmas Special for ABC, to get it done on time. On Roger Rabbit, the live action director stayed intimately involved in the animation after his shoot was complete. When it became obvious that things weren’t going well, he stepped in to complete that film.

In all cases of all of these films, Dick never left. He stayed on working separately on animation or assisting to try to keep a positive hand in the quality of the work that was done.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

When The Cobbler and the Thief ran into very serious trouble, there was no secondary Director or Producer to come in and complete the work. Instead that job fell to the money men. The completion bond company, essentially an insurance company for Warner Bros. to make sure they wouldn’t lose their money if things didn’t go well, stepped in. They closed Dick’s studio and removed Dick from the premises. The boxed up and carted off all animation work done or in progress. It was all moved back to Los Angeles.

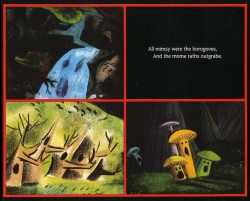

The Weinsteins, through their company, Miramax bought the film at auction and completed it with a poor excuse of an animation outfit they set up in LA. Work was also sent to Taiwan. The script was reworked trying to capitalize on the success of Disney’s Aladdin that had recently opened in the US. If Robin Williams‘ ad libbing could be such a success, imagine how well Jonathan Winters could do repeating that for a character who, in Dick’s original version, had no voice. Now he didn’t stop talking.

The new film failed miserably and deserved to do so. The primary audience, I would suspect, was the entire world animation community coming to look down on the artificially breathing corpse.

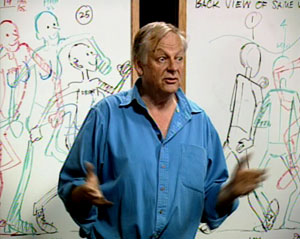

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

Richard Williams, himself, retired and moved far from the mainstream. He continues to work on small animation bits, but his primary work has been in making a series of DVD lectures revealing how animation should be done. This accompanies a well-received book he wrote and illustrated. Meanwhile, the animation community still hopes that something will emerge from that corner.

Dick turns 80 years old on March 19th. He’s still an amazing forceful and exciting personality. I wish I had more access to him (as does most of those who knew him back then.) He’s had probably the greatest effect on the animation industry of anyone since the late sixties. There are still studios thriving today on information they learned from Dick and his teaching.

If you’re unfamiliar with the blog, The Thief, I suggest you take a look.