Bridget’s Art

It’s time to put up some more Sporn Studio art. I had a couple of posts that celebrated BG art of Bridget Thorne. I’m putting a couple of these together and posting anew. Personally, I love this stuff and can’t get enough of it. I want to see Bridget doing BGs again; it’s been a while.

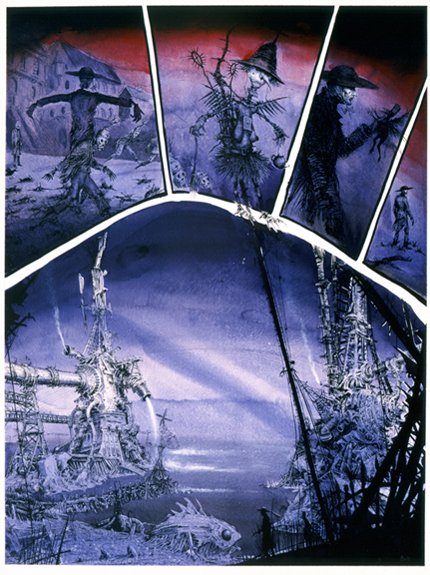

Bridget Thorne did the storyboard for

The Hunting of the Snark with me back in 1980.

We didn’t finish the film until 1989. She also painted the

backgrounds for the last third of the movie.

Bridget Thorne is someone who has been an invaluable part of the history of my films.

She has been an extraordinary Art Director and Background painter on quite a few of my favorite films produced within the studio, and I’ve put together a random sampling of some of those films.

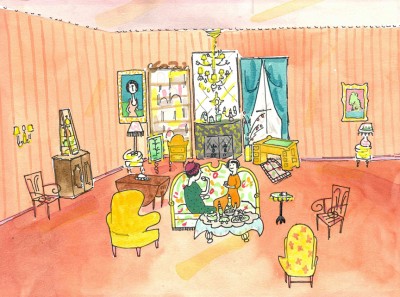

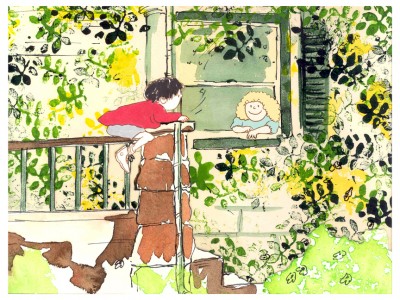

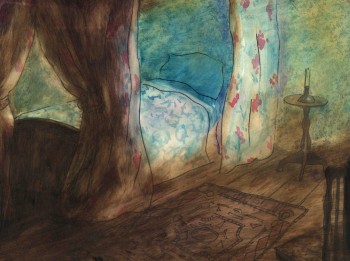

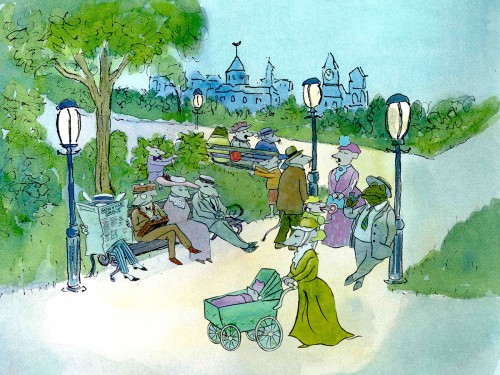

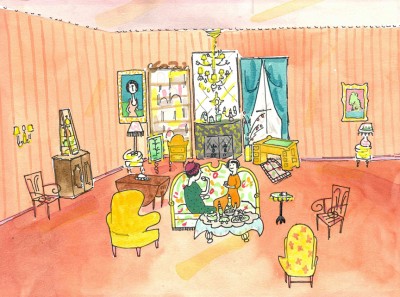

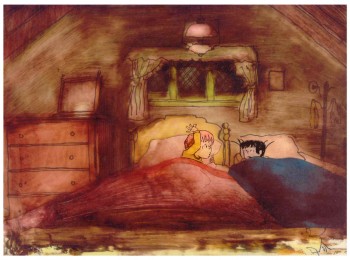

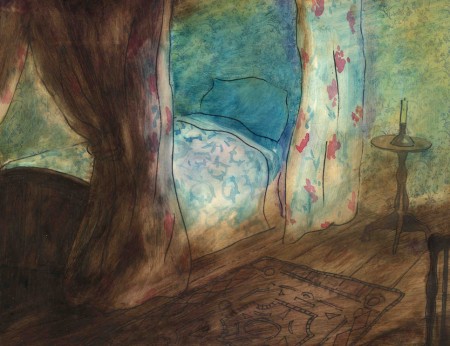

(Click image to enlarge) Lyle, Lyle Crocodile (1987)

This painting is a key transition point in Lyle, Lyle Crocodile. The film had a looseness  that Bernard Waber‘s original book art had engendered. I felt very much at home in Waber’s style, and I think Bridget did as well.

that Bernard Waber‘s original book art had engendered. I felt very much at home in Waber’s style, and I think Bridget did as well.

She worked out a color scheme for the film, and we both agreed to follow it closely through the film. Liz Seidman lead the character coloring. Bridget, of course, had a strong hand in all those character models, as well.

The scene pictured above follows the introduction of Autumn on “East 88th Street”, and the background brings us full force into it as we get “the girl’s first song” – Mrs. Primm’s report on what it’s like to have a crocodile living in your house.

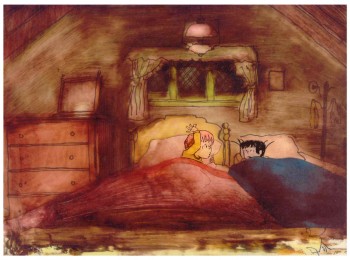

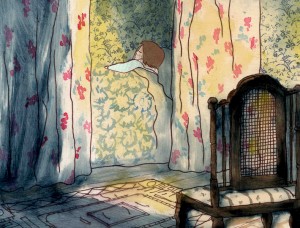

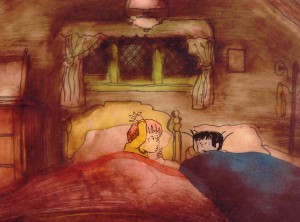

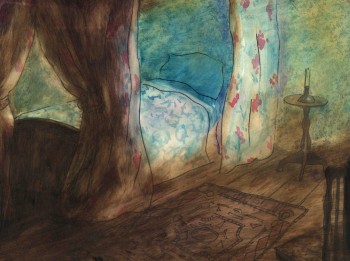

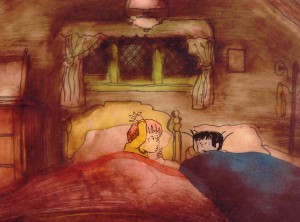

– Ira Sleeps Over was the second children’s book by Bernard Waber that we adapted. This is a very sweet story which involves a sibling rivalry; it focusses on a teddy bear and a sleep-over party. I pulled composer, William Finn, into the film and he wrote some great tunes for it. Prior to doing the script, I gave him the book and asked him to figure out where he would like the songs. In a week he had already written all the songs for the film, and they were brilliant. It turned out he used all the words of the book in his songs, and now I had to find a way of telling the same story using past, present and future tenses, as he did in the songs. It was a good challenge that worked out well and created a fabulous construction for the story.

– Ira Sleeps Over was the second children’s book by Bernard Waber that we adapted. This is a very sweet story which involves a sibling rivalry; it focusses on a teddy bear and a sleep-over party. I pulled composer, William Finn, into the film and he wrote some great tunes for it. Prior to doing the script, I gave him the book and asked him to figure out where he would like the songs. In a week he had already written all the songs for the film, and they were brilliant. It turned out he used all the words of the book in his songs, and now I had to find a way of telling the same story using past, present and future tenses, as he did in the songs. It was a good challenge that worked out well and created a fabulous construction for the story.

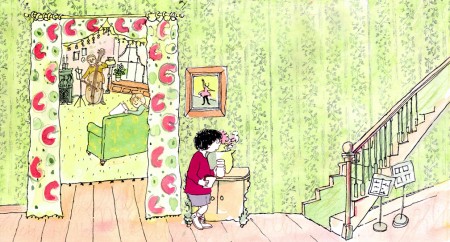

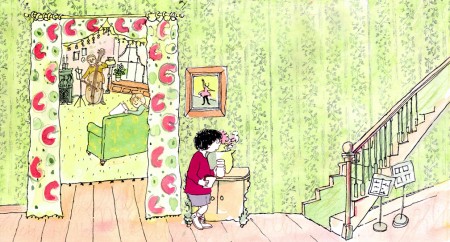

The style in this book was, if anything, looser than in Lyle. Waber did a lot of his illustration featuring duplicating printing techniques. Lino cut enabled him to repeat decorations throughout the settings. Bridget played with the lino cuts and was able to succesffully duplicate the technique in the backgrounds. In this one bg, at the beginning of the film, the foliage is a good example of this technique, printed over watercolors. The characters are markered paper drawings cut out and pasted to the cel overlays.

The style in this book was, if anything, looser than in Lyle. Waber did a lot of his illustration featuring duplicating printing techniques. Lino cut enabled him to repeat decorations throughout the settings. Bridget played with the lino cuts and was able to succesffully duplicate the technique in the backgrounds. In this one bg, at the beginning of the film, the foliage is a good example of this technique, printed over watercolors. The characters are markered paper drawings cut out and pasted to the cel overlays.

The book, like Lyle, featured a lot of white space, so we followed suit. When a book’s been in circulation for over 25 years, you have to realize there’s been a reason for it; find the reason and the heart, and take advantage of it. This use of white space made the actual backgrounds oftentimes little more than abstract shapes of color with a solid object on the screen. Here, for example, we see Ira and his friend, Reggie, playing against a blast of green and a bicycle.

– At the end of the film, Ira and Reggie talk in the dark at the sleep-over. To get the look of the dark Bridget had to come up with something clever. The book resorted to B&W washes of gray and wasn’t very helpful. She came up with some dyes that were used for photo retouching. By quickly painting these lightly onto cel levels with a wide brush, she was able to get translucent cels with the brush strokes imbedded in the color overlays. By placing these overlays over the characters and backgrounds, we got the desired effect that let it feel connected to the very loose style of the film.

– At the end of the film, Ira and Reggie talk in the dark at the sleep-over. To get the look of the dark Bridget had to come up with something clever. The book resorted to B&W washes of gray and wasn’t very helpful. She came up with some dyes that were used for photo retouching. By quickly painting these lightly onto cel levels with a wide brush, she was able to get translucent cels with the brush strokes imbedded in the color overlays. By placing these overlays over the characters and backgrounds, we got the desired effect that let it feel connected to the very loose style of the film.

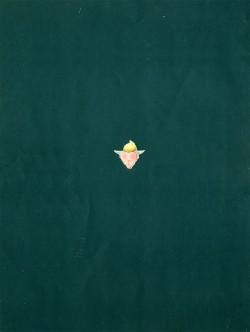

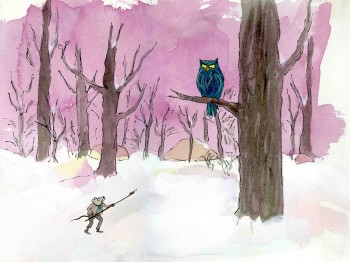

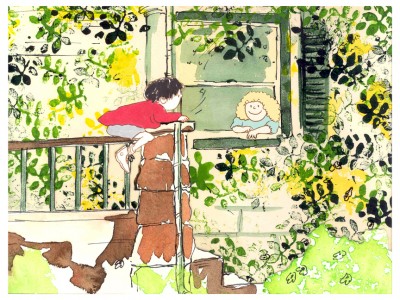

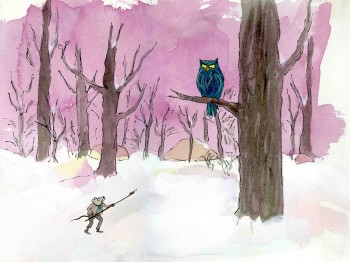

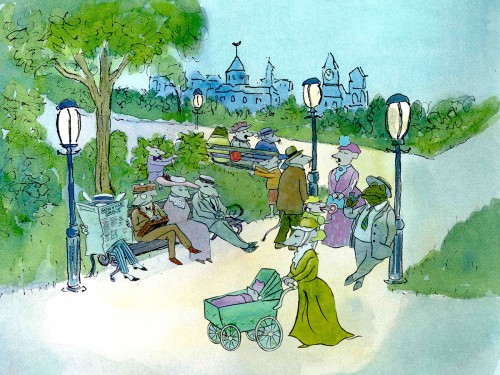

-Abel’s Island is one of the few films we did that I treasure for its artwork. Bridget’s work on the backgrounds was, to me, extraordinary. The looseness I love was developed into enormously lush backgrounds using shades of green that I didn’t know could be captured in the delicate watercolors.

-Abel’s Island is one of the few films we did that I treasure for its artwork. Bridget’s work on the backgrounds was, to me, extraordinary. The looseness I love was developed into enormously lush backgrounds using shades of green that I didn’t know could be captured in the delicate watercolors.

This film was a complicated problem that seemed to resolve itself easily and flow onto the screen without much struggle. The book had won a Newberry Award as best children’s writing of its year. It was not a picture book but a novel. The more than 120 pages featured fewer than 20 B&W spot drawings by author/illustrator, William Steig. We were on our own with the color.

However, we had adapted Doctor DeSoto and The Amazing Bone as shorter films and could use what we’d learned from Steig on Abel. Bridget topped herself.

However, we had adapted Doctor DeSoto and The Amazing Bone as shorter films and could use what we’d learned from Steig on Abel. Bridget topped herself.

Several of the animators gave us more than I could have expected. Doug Compton‘s animation of Abel sculpting his statuary and living in his log was heart rending; Lisa Craft‘s animation of the big pocket watch, the big book and the leaf flying sequences was nothing short of inspired; and John Dilworth‘s animation of the owl fight was harrowing. This was all set up and completed by Tissa David‘s brilliant animation of Abel in the real world with wife, Amanda. She established our character.

– At the end of the film, Abel, who has been separated from his new bride, trapped on an island for over a year, finally gets to come home. He sees Amanda in a park at twilight but decides to hold back. He races on ahead of her to greet her, privately, at home. The park sequence has a busyness as an acute counter to the lonliness we’ve watched for the previous 90% of the half-hour program. Setting it at early evening gave an opportunity for rich, royal colors. Bridget took full advantage of the opening, and underscored it all with a regal green not seen earlier. It was stunning and is one of my favorite backgrounds in the film.

– At the end of the film, Abel, who has been separated from his new bride, trapped on an island for over a year, finally gets to come home. He sees Amanda in a park at twilight but decides to hold back. He races on ahead of her to greet her, privately, at home. The park sequence has a busyness as an acute counter to the lonliness we’ve watched for the previous 90% of the half-hour program. Setting it at early evening gave an opportunity for rich, royal colors. Bridget took full advantage of the opening, and underscored it all with a regal green not seen earlier. It was stunning and is one of my favorite backgrounds in the film.

Here are two more films Bridget Thorne designed for me.

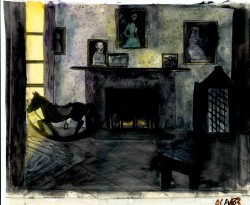

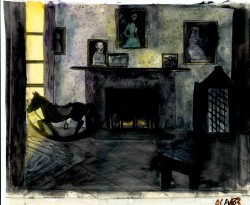

A Child’s Garden of Verses presented new and different problems to explore.

A Child’s Garden of Verses presented new and different problems to explore.

It was a project generated by HBO. Charles Strouse and Thomas Meehan were going to write the book and song score. We met several times trying to discover a way into the book of poems. I’d suggested we use the verses in Robert Louis Stevenson‘s book to illustrate the author’s early childhood.

(Click on any image to enlarge.)

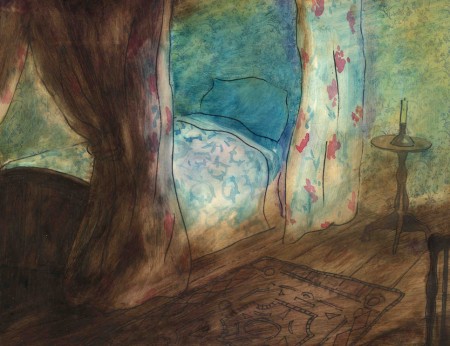

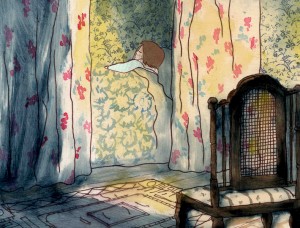

Stevenson was a sickly boy who was always confined to his dark room. He was not expected to live long. The only visitor for days on end was his overprotective mother.

Stevenson was a sickly boy who was always confined to his dark room. He was not expected to live long. The only visitor for days on end was his overprotective mother.

For much of the film, we had only the dark, child’s bedroom to explore. Artistically, I asked Bridget to delve deeper into the photgraphic dyes that she had discovered and used so well in Ira Sleeps Over. These dyes would allow us to keep the style, once again, loose while exploring dark areas and brush strokes to simulate the darkness “Robbie” lived in.

For the wallpaper throughout the house, Bridget used real wallpaper which was photostated; scaled down and reshaped to fit the backgrounds. Then watercolor washes colored these backgrounds and overlays were mixed and matched to get the desired results.

I was never quite pleased with this film. The elements that worked well worked really well. Bridget’s work was a highlight. The acting was extraordinarily good. Heidi Stallings performed with an enormous amount of emotion yet barely raised her voice above a whisper. Jonathan Pryce was brilliant as Robert Louis Stevenson, the narrator and even sang a song when asked at the last minute. Gregory Grant as the young “Robbie” was vulnerable, sweet and all we could have hoped for.

I was never quite pleased with this film. The elements that worked well worked really well. Bridget’s work was a highlight. The acting was extraordinarily good. Heidi Stallings performed with an enormous amount of emotion yet barely raised her voice above a whisper. Jonathan Pryce was brilliant as Robert Louis Stevenson, the narrator and even sang a song when asked at the last minute. Gregory Grant as the young “Robbie” was vulnerable, sweet and all we could have hoped for.

However, there was too much of a rush given the delicacy of the piece, and the exterior backrounds done by me for the end of the film are poor. The animation is also hit and miss. Oddly enough, my favorite sequence used little actual animation but intense camera work. Ray Kosarin was the animator in charge of it, and it’s an impressive sequence.

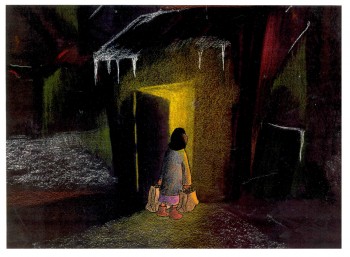

- The Talking Eggs was done for a PBS series called Long Ago & Far Away. It was an adaptation of a Creole Folk Tale which Maxine Fisher updated for me. (Lots of discussion between WGBH, Maxine & me about what distinguishes a Folk Tale from a Fairy Tale. It seriously impacted the story we were telling and I wanted what I wanted and got.)

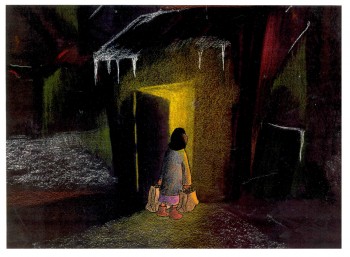

Bridget chose to use pastels and we searched for a paper that would bring out the most grain. I loved the end result. The characters, to match the look of the Bgs, were xeroxed onto brown kraft paper and colored up from there with prismacolor pencils. This was cut out and pasted to cel.

Danny Glover was the narrator, and we chose to make him an on-screen character appearing intermitently in the film. His narration was recorded on a rush as he stopped off in LA from SF on his way to direct a film in Africa.

Danny Glover was the narrator, and we chose to make him an on-screen character appearing intermitently in the film. His narration was recorded on a rush as he stopped off in LA from SF on his way to direct a film in Africa.

There’s a focus in these backgrounds that matches the content and mood of the piece, and it worked wonderfully for my purposes. I always like it when the medium is front and center; I want audiences to know that they’re watching animated drawings, and texture usually helps to do this. Of course, I also want the films to have a strong enough story that the audience gets past the point of knowing, to enter the film. It works some of the time, and I’m in heaven when it does.

Bridget altered the color of the paper on which she was coloring with the chalks, and the different colored papers represented varied moods from sequence to sequence.

Bridget altered the color of the paper on which she was coloring with the chalks, and the different colored papers represented varied moods from sequence to sequence.

Naturally, there were some problems with the chalks under camera. All the fixative in the world didn’t stop the chalks from bleeding onto the cels or platen on the camera. (Lots more cleaning involved than usual.) We heard constantly from our cameraman, Gary Becker. The extra effort was worth it; the look was unique and successful.

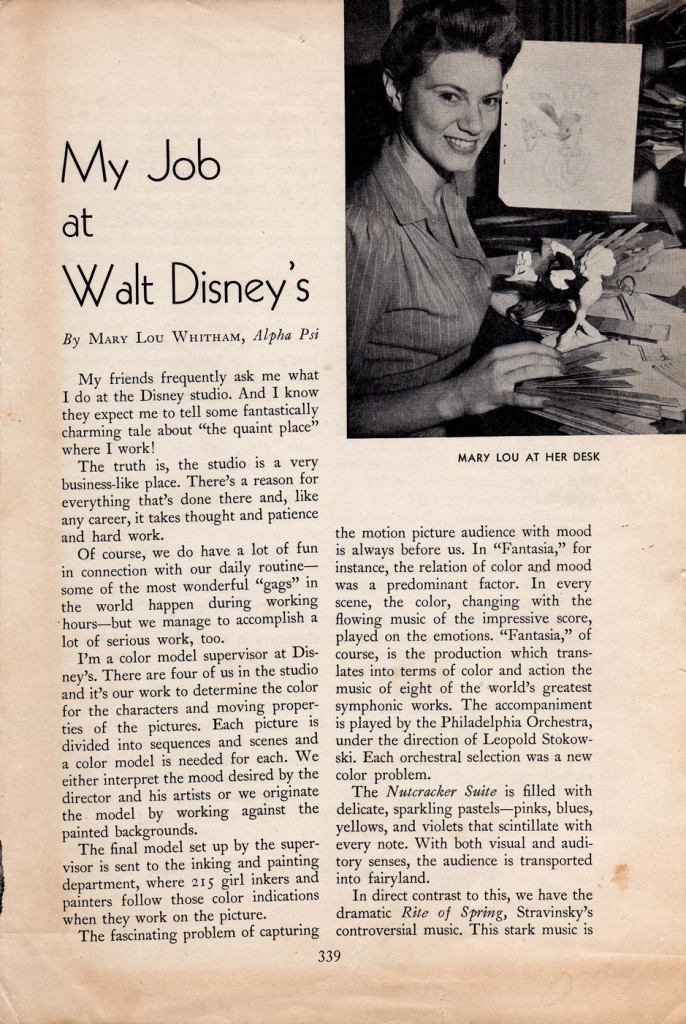

The following is a short interview that we did in a publication I generated back in the ’80s.

Background Information:

Behind the Scenes with

Bridget Thorne

Interview by Denise Gonzalez

Bridget Thorne is a background designer who has been an important part of Michael Spom Animation for more than fifteen years. In that time she has enhanced the look of MSA films with beautiful backgrounds that are, in a way, part of the characters rather than just a scenic backdrop.

DG: How long have you been working with Michael Sporn?

DG: How long have you been working with Michael Sporn?

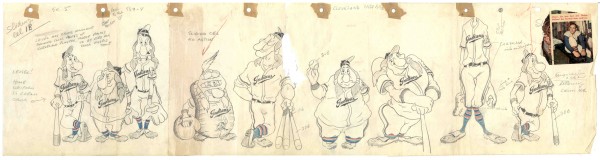

BT: I first started working for Michael in 1979 on Byron Blackbear And The Scientific Method, a fifteen minute short for the Learning Corporation of America. It is actually one of my favorites. I started out as a scenic painter for plays. I worked with a designer and basically dressed the set. We’d paint the exteriors, lay in wallpaper, marbleizing floors, etc. I started at Williamstown and at Playwright’s Variety in New York, I did a lot of off Broadway and off-off Broadway.

DG: Do you see background painting as a complete picture or as a supplement to animated artwork?

BT: It’s a supplement.

DG: How do you take that into consideration when you start the backgrounds?

DG: How do you take that into consideration when you start the backgrounds?

BT: Ideally, I take into consideration how the characters are designed. I like the characters to be part of the picture, not stand out like they do in Saturday morning cartoons. It all fits into a stylistic sensibility or pace more than anything else. I’m not a cartoon snob, I’m more of a two dimensional artist than a filmmaker. I design my backgrounds and line style according to the way the characters are designed. What I used to try and do was color the backgrounds, to match the colors of the characters. You work out of your home rather than at the studio. What are the benefits or drawbacks of working this way? I’ve just started doing this and yes, there are benefits. I can get into my own head, and I take off more with ideas because I’m not interrupted as much. But I like being in the studio and staying with the rest of the production as it goes along.

DG: Do you prefer working on original stories or from an existing book?

BT: It depends on the story. Let’s say IRA SLEEPS OVER, it was great working out here on that because with an existing story you have a style to imitate, and it is easy for a whole bunch of people to follow that when they’re all working in different places. So as far as production goes, that makes it easier. The great thing about original scripts is that they allow for an incredible amount of individual input. What do you take into consideration when designing the look of a film and what preparation is involved? It depends on the story. I tend to have a knee jerk reaction at first or an impulse. I have a Fine Arts background, and I tend to rely on painters. I find fine artists are more in tune stylistically with Michael’s films than the more hard-edged graphic cartoons. (Though I will look at Disney inspirational drawings.)

BT: It depends on the story. Let’s say IRA SLEEPS OVER, it was great working out here on that because with an existing story you have a style to imitate, and it is easy for a whole bunch of people to follow that when they’re all working in different places. So as far as production goes, that makes it easier. The great thing about original scripts is that they allow for an incredible amount of individual input. What do you take into consideration when designing the look of a film and what preparation is involved? It depends on the story. I tend to have a knee jerk reaction at first or an impulse. I have a Fine Arts background, and I tend to rely on painters. I find fine artists are more in tune stylistically with Michael’s films than the more hard-edged graphic cartoons. (Though I will look at Disney inspirational drawings.)

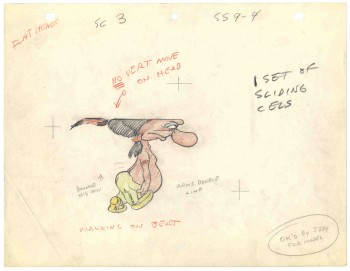

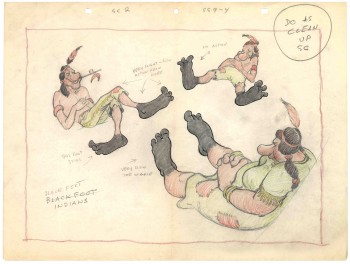

Then I look at the layouts and the character design, so I sort of work on intuition and impulse. Then I look at the existing elements and put those all together and come up with a design. As far as preparation goes, what I consistently do is make 5×4 sketches of design ideas. For ABEL’S ISLAND I did lots and lots of little paintings of winter and fall and spring.

First three illustrations pictured above:

1. BYRON BLACKBEAR AND THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD.

2. A CHILD’S GARDEN OF VERSES.

3. IRA SLEEPS OVER

DG: When designing the film do you take into consideration that this will be seen by a child?

BT: I’m not a cartoony person so I don’t think about that. I tend to think more — sometimes I run into trouble this way — I think of it in a frame and ideally what I really want is a balanced look on the screen. A lot of times that’s hard because what I see in front of me is so different when it is filmed.

DG: What do you consider to be the best example of your work thus far?

BT: I guess ABEL’S ISLAND. I was able to abstract a little. I wasn’t confined to chairs and bureaus. I was able to match the mood of the movie to the backgrounds. If Abel was in trouble, I could put colors that indicated that, or I could abstract it. If something was calm I could paint it calmly. Abstraction, or looseness, is more my personal style. This is true of Michael’s style, as well.

A scene toward the end of ABEL’S ISLAND.

DG: Have you ever worked on a film you couldn’t connect with?

BT: I’d say yes. It’s a hard question to answer off the top of my head. I sort of think of movies like they were kids; they are either noisy or funny or quiet or sad. They all have their own characteristics, and it is really the process of making the movie that attracts me to animation. I tend to have different feelings about each movie. But yes, sometimes a story irritates me or something comes in and it doesn’t suit my style or what I imagined. It can be very difficult. That’s an interesting thing about animation; there is really a sense of compromise; you are compromising all the time.

A scene of the narrator at the end of THE TALKING EGGS.

A background from A CHILD’S GARDEN OF VERSES.

home from school in WHITEWASH.

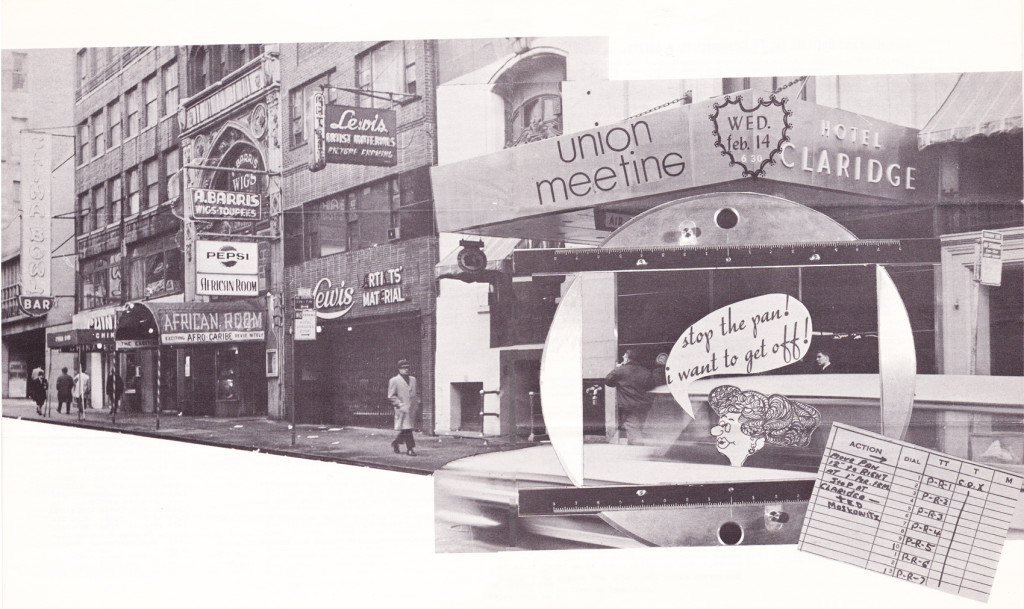

- Back in the olden days, films were released very differently.

- Back in the olden days, films were released very differently.  1

1  2

2 9

9  10

10