- It’s been a while since I’ve posted anything about stop-motion animation, and seeing an attractive poster for Coraline made me realize it was time. I’ve recently posted some articles from the Millimeter/1975 animation issue which was edited by John Canemaker. This is another excellent piece from the same magazine, and I think it a good one.

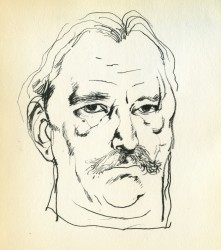

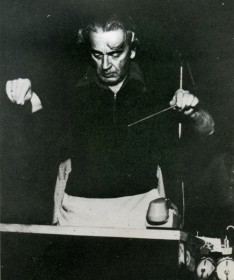

Ray Harryhausen

An Interview with the Master of Stop-Motion Animation

by Mark Carducci

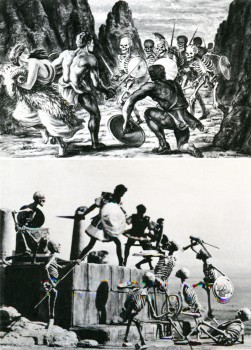

Film history records the earliest three-dimensional animator as George Melies, the showman-turned-filmmaker of A TRIP TO THE MOON fame. Melies, unlike many special-effects men of today, realized the value in using several different effects processes at the same time. Thus he would utilize stop-action, animation, miniature photography and mechanical effects all in the same frame. Melies was a pioneer in the field of effects animation in three dimensions, and he paved the roads other animators would one day travel. One such traveler was Willis H. O’Brien. O’Brien single-handedly elevated the techniques of three-dimensional model animation to a fine art, beginning in the silent era with short subjects and continuing through the 1925 classic THE LOST WORLD to KING KONG a mere eight years later. As Kong was king of Skull Island, so O’Brien was king of model manipulation, and tike Melies before him, O’Brien never missed an opportunity to add drama, atmosphere or pathos by mixing effects together. Witness the clash between Kong and a flying reptile atop Kong’s mountain lair: Kong and the pterodactyl are jointed foot-high foam rubber models; the mountain’s ledge is a plaster recreation; the sky background is a painting on glass; the flying reptiles in the sky are double-printed eel animation. It was this intelligent and intentional combining of effects that allowed O’Brien to achieve the marvelous sense of reality he did in KING KONG, a reality so intense as to make a thirteen-year-old named Raymond Harryhausen choose the field of special effects animation as his life’s work.

Film history records the earliest three-dimensional animator as George Melies, the showman-turned-filmmaker of A TRIP TO THE MOON fame. Melies, unlike many special-effects men of today, realized the value in using several different effects processes at the same time. Thus he would utilize stop-action, animation, miniature photography and mechanical effects all in the same frame. Melies was a pioneer in the field of effects animation in three dimensions, and he paved the roads other animators would one day travel. One such traveler was Willis H. O’Brien. O’Brien single-handedly elevated the techniques of three-dimensional model animation to a fine art, beginning in the silent era with short subjects and continuing through the 1925 classic THE LOST WORLD to KING KONG a mere eight years later. As Kong was king of Skull Island, so O’Brien was king of model manipulation, and tike Melies before him, O’Brien never missed an opportunity to add drama, atmosphere or pathos by mixing effects together. Witness the clash between Kong and a flying reptile atop Kong’s mountain lair: Kong and the pterodactyl are jointed foot-high foam rubber models; the mountain’s ledge is a plaster recreation; the sky background is a painting on glass; the flying reptiles in the sky are double-printed eel animation. It was this intelligent and intentional combining of effects that allowed O’Brien to achieve the marvelous sense of reality he did in KING KONG, a reality so intense as to make a thirteen-year-old named Raymond Harryhausen choose the field of special effects animation as his life’s work.

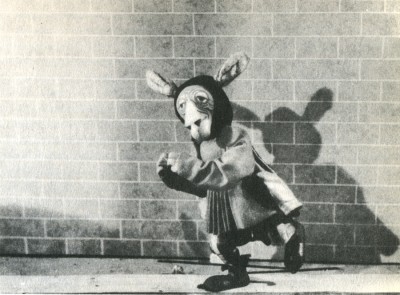

From the time he saw KING KONG in 1933, until the mid-40′s, the youthful Harryhausen animated in what might be called a highly animated fashion.

He even managed, on several occasions, to gain an audience with his future mentor. Though Ray’s fledgling efforts were crude, O’Brien saw in them a promise of future greatness, and he was quick to offer constructive advice to his precocious- protege whenever he was asked. In 1946, impressed by Ray’s solo efforts in producing a series of animated fairy tales; O’Brien offered him encouragement of a more concrete nature: a position as an animator on the Merian C. Cooper production MIGHTY JOE YOUNG. Of this opportunity-of-a-lifetime Harryhausen recalls: “It was, of course, the climax of a long-awaited dream come true. I had a magnificent two-year period of working with O’Brien, during the long pre-production and design stage, up to the end of animation photography. He was so involved in production problems that I ended up animating aboul 80% of the picture.”

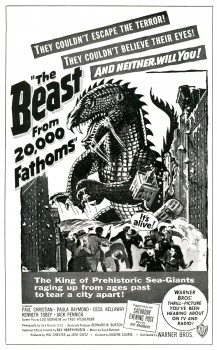

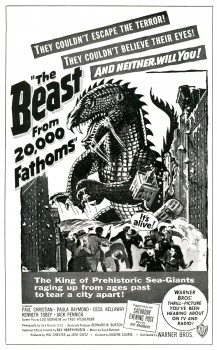

In 1952, as a result of his Oscar-winning work on MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (Best Special Effects of 1949) Ray was approached by Jack Dietz and asked to create the effects for THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. These he executed ably, employing an innovative front-projection system of his own design, as the preferable but more expensive rear-project ion equipment the work called for was outside the boundaries of Dietz’s budget. THE BEAST came in at $200,000, a remarkably low figure considering the expertise and high quality of Ray’s animation and effects. Audiences of 1952 flocked to the picture in droves, making it the unexpected sleeper of the year for Warner Brothers. Completing THE BEAST left Ray on the brink of a long, creatively satisfying and financially rewarding association with a then-youthful producer, Charles Schneer.

In 1952, as a result of his Oscar-winning work on MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (Best Special Effects of 1949) Ray was approached by Jack Dietz and asked to create the effects for THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. These he executed ably, employing an innovative front-projection system of his own design, as the preferable but more expensive rear-project ion equipment the work called for was outside the boundaries of Dietz’s budget. THE BEAST came in at $200,000, a remarkably low figure considering the expertise and high quality of Ray’s animation and effects. Audiences of 1952 flocked to the picture in droves, making it the unexpected sleeper of the year for Warner Brothers. Completing THE BEAST left Ray on the brink of a long, creatively satisfying and financially rewarding association with a then-youthful producer, Charles Schneer.

Schneer wished to produce a script about a giant octopus that terrorizes San Francisco, and after meeting hirn^ {Schneer, not the octopus) Ray agreed to work on the picture. The result was IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA, the first of a series of ten feature films produced by Schneer with special visual effects by Ray Harryhausen. Along the way, Ray has freelanced twice: once in 1958 to animate the dinosaur sequences in Irwin Allen’s THE ANIMAL WORLD, and again in 1966 to handle effects on Hammer Film’s OWE MILLION YEARS B.C.

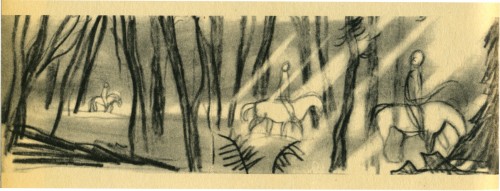

A comparison of the work of Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien yields some interesting observations. One of O’Briens trademarks throughout, his career was his use of glass paintings. The three-dimensional effect of the jungles of Skull Island was achieved through the painting, on glass, of dense trees and vines. By animating his models behind several layers of these realistic depictions of forest, O’Brien was able to achieve an illusion of depth that added tremendously to the dramatic impact of the entire film. O’Brien was a dramatic romantic, and a stickler for any detail •haqlbuld romanticize. Harryhausen, on •hefOtner hand, is a realist, and in his Jiifork there is a sense of reserve; of a wpjehful eye on the cost of each particular effect. No layers of intricate glass paintings for him—too expensive. For Ray’s purposes a simple but effective matte painting will suffice. The net result is always a little less atmospheric than O’Brien’s work and ultimately less powerful. To compensate for this Harryhausen outshines his master in the fluidity of his animation. His smoothness of movement of his foam rubber creatures is the most striking difference between his and O’Brien’s digital prestidigitation. In this area the pupil could have taught his teacher.

A comparison of the work of Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien yields some interesting observations. One of O’Briens trademarks throughout, his career was his use of glass paintings. The three-dimensional effect of the jungles of Skull Island was achieved through the painting, on glass, of dense trees and vines. By animating his models behind several layers of these realistic depictions of forest, O’Brien was able to achieve an illusion of depth that added tremendously to the dramatic impact of the entire film. O’Brien was a dramatic romantic, and a stickler for any detail •haqlbuld romanticize. Harryhausen, on •hefOtner hand, is a realist, and in his Jiifork there is a sense of reserve; of a wpjehful eye on the cost of each particular effect. No layers of intricate glass paintings for him—too expensive. For Ray’s purposes a simple but effective matte painting will suffice. The net result is always a little less atmospheric than O’Brien’s work and ultimately less powerful. To compensate for this Harryhausen outshines his master in the fluidity of his animation. His smoothness of movement of his foam rubber creatures is the most striking difference between his and O’Brien’s digital prestidigitation. In this area the pupil could have taught his teacher.

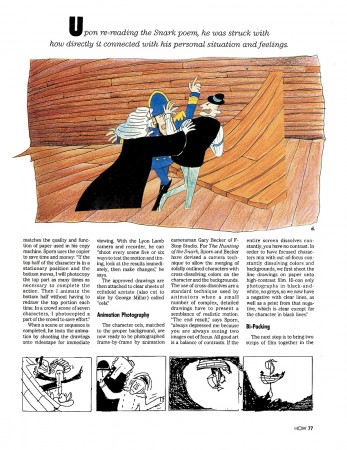

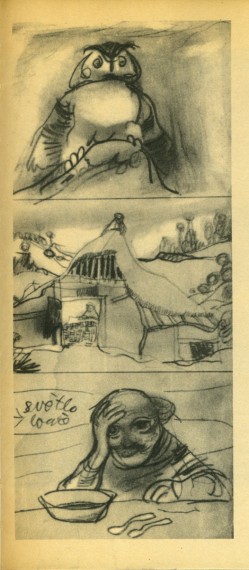

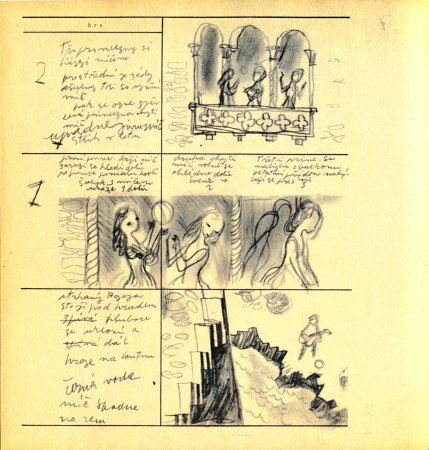

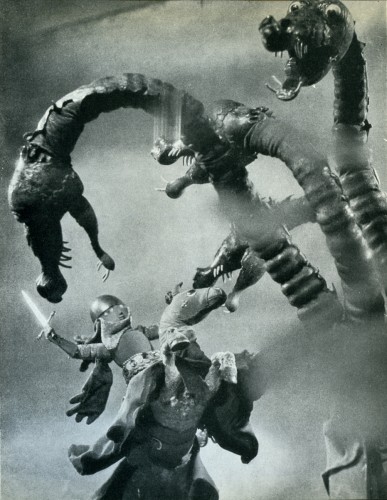

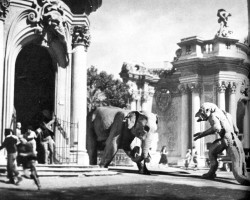

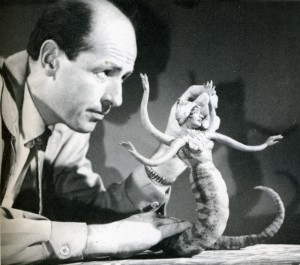

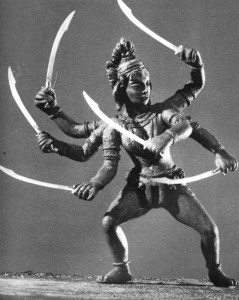

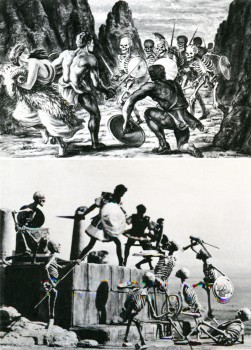

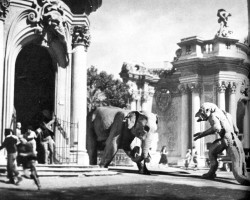

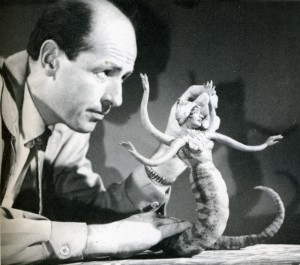

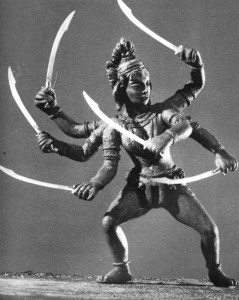

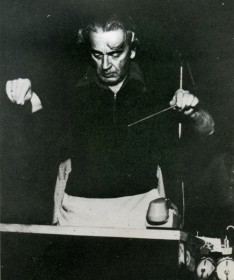

The exact processes by which Harryhausen combines his animated models with live actors are ones he prefers to anyone with a basic of animation can grasp the*1 rudiments of what Schneer and Harryhausen have dubbed “Dynarama.” Let us take an example from Harry-hausen’s latest film, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. The script called for a battle between Sinbad and a giant one-eyed centaur. The first step in creating the illusion of a human dueling with a mythical monster was to film the actor, in this case John Philip Law, leaping to and fro fighting with an imaginary creature. The resulting footage is loaded onto a rear-screen projector which has been modified to move a frame at a time instead of at sound speed. In front of this rear screen, Harryhausen constructs a miniature set, which corresponds to the full-size one on the film in the projector. Placing his foot-and-a-half tall centaur into this miniature setting, Harryhausen animates it a frame at a time, being careful to similarly advance the rear-projected image of Sinbad. Re-photographing this entire set-up with a locked down animation camera produces the desired effect. This description can only serve to illustrate the bare bones of the Dynarama process. Many sequences have required much more complex techniques of Ray and his equipment. As a result the time element involved in the production of a Dynarama picture is staggering. Pre-production lasts six months to a year. Principal photography lasts several months and the animation photography consumes an incredible year or more! But the results, which speak for themselves, have always seemed to justify the commitment of two or three years of Ray Harryhausen’s life; at least in the past they have.

The exact processes by which Harryhausen combines his animated models with live actors are ones he prefers to anyone with a basic of animation can grasp the*1 rudiments of what Schneer and Harryhausen have dubbed “Dynarama.” Let us take an example from Harry-hausen’s latest film, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. The script called for a battle between Sinbad and a giant one-eyed centaur. The first step in creating the illusion of a human dueling with a mythical monster was to film the actor, in this case John Philip Law, leaping to and fro fighting with an imaginary creature. The resulting footage is loaded onto a rear-screen projector which has been modified to move a frame at a time instead of at sound speed. In front of this rear screen, Harryhausen constructs a miniature set, which corresponds to the full-size one on the film in the projector. Placing his foot-and-a-half tall centaur into this miniature setting, Harryhausen animates it a frame at a time, being careful to similarly advance the rear-projected image of Sinbad. Re-photographing this entire set-up with a locked down animation camera produces the desired effect. This description can only serve to illustrate the bare bones of the Dynarama process. Many sequences have required much more complex techniques of Ray and his equipment. As a result the time element involved in the production of a Dynarama picture is staggering. Pre-production lasts six months to a year. Principal photography lasts several months and the animation photography consumes an incredible year or more! But the results, which speak for themselves, have always seemed to justify the commitment of two or three years of Ray Harryhausen’s life; at least in the past they have.

At present Ray is involved in yet a third film about the adventures of the swashbuckling Sinbad, though he characteristically refuses to give details about the project. This is understandable, since at the time we spoke he didn’t even have a story-line. This, too, is characteristic; perhaps unfortunately so. For it is in this area, the script, that Ray’s films have shown their vulnerable underbellies. Starting as they do with Ray’s sketches of the fantastic monsters involved, most Dynarama films are built around a monster or monsters on the loose. Plot, dialogue and characterization have always played second fiddle to special effects in Harryhausen’s films, and this is nowhere as painfully obvious as in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. Although his cart-before-the-horse method of scripting has always netted Harryhausen films of a very satisfying financial nature, it has never netted him a film with the impact and scope of KING KONG, and never will. One can only hope that as he has more say in his productions than any effects animator on earth, (he is a co-producer) Harryhausen will one day put as much creative energy into his script, casting and choice of director, as he does into his visuals. Perhaps then the day may yet come when Dynarama films will have some saving graces beyond their impressive opticals. Be that as it may, for anyone at all interested in animation and effects cinematography, the words of the grandmaster of Dynarama paint a fascinating portrait of a seldom glimpsed phase of film production.

At present Ray is involved in yet a third film about the adventures of the swashbuckling Sinbad, though he characteristically refuses to give details about the project. This is understandable, since at the time we spoke he didn’t even have a story-line. This, too, is characteristic; perhaps unfortunately so. For it is in this area, the script, that Ray’s films have shown their vulnerable underbellies. Starting as they do with Ray’s sketches of the fantastic monsters involved, most Dynarama films are built around a monster or monsters on the loose. Plot, dialogue and characterization have always played second fiddle to special effects in Harryhausen’s films, and this is nowhere as painfully obvious as in THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD. Although his cart-before-the-horse method of scripting has always netted Harryhausen films of a very satisfying financial nature, it has never netted him a film with the impact and scope of KING KONG, and never will. One can only hope that as he has more say in his productions than any effects animator on earth, (he is a co-producer) Harryhausen will one day put as much creative energy into his script, casting and choice of director, as he does into his visuals. Perhaps then the day may yet come when Dynarama films will have some saving graces beyond their impressive opticals. Be that as it may, for anyone at all interested in animation and effects cinematography, the words of the grandmaster of Dynarama paint a fascinating portrait of a seldom glimpsed phase of film production.

M.C.: Have you ever considered remaking the film which first inspired you, KING KONG?

R.H.: Yes, but KONG couldn’t be re-made today without spending vast amounts of money. The time and cost involved in doing all those glass paintings would be astronomical. You know O’Brien really developed the technique of glass painting single-handedly. In a way his use of them was a forerunner of Disney’s multi-plane camera. On KONG Obie had animation tables sandwiched between the glass paintings, and on these tables he’d place his models. He needed a tremendous amount of light for the camera to record through all those panes of glass. Often a light would blow in the middle of a scene, ruining a shot he had worked on for days. To remake KONG would be much too complex a thing to get into today.

M.C.: Some hold the opinion that your films have little merit aside from their impressive effects. I don’t mean to criticize, but I tend to agree with that, excepting MYSTERIOUS ISLAND, a Him I feel could stand alone if the footage of the monsters was cut.

R.H.: Really? I don’t think you would feel that way about MYSTERIOUS ISLAND if you actually did cut that footage. Pick up an 8mm version some time and try it. (Laughs) The original Jules Verne novel was really just a tale of survival on a desert island. The survivors in the story saw rather mundane things, so we modified their adventures a bit by adding Capt. Nemo and his giant creatures.

M.C.: With newer and better emulsions now available in 16mm, have you considered working in that gauge?

M.C.: With newer and better emulsions now available in 16mm, have you considered working in that gauge?

R.H.: No, I have no reason to work in 16mm. With 16 you don’t have the options and accuracy of 35mm and the optical printer. Certain subjects might show up quite well on a blow-up from 16, but my work is much too complicated to further complicate it by working in a smaller gauge than 35mm.

M.C.: What about 70mm?

R.H.: We released FIRST MEN IN THE MOON in 70mm, but that was a blow-up from 35. Shooting on a 70mm negative is too costly a proposition, necessitating the use of too many specialized pieces of equipment.

M.C.: FIRST MEN was shot in Panavision. What effect did shooting wide screen have on your usual methods?

R.H.: I was forced to re-design many things, because certain techniques are impractical in Panavision. I relied more heavily on traveling matte work in FIRST MEN, whereas normally I might have used front or rear projection.

M.C.: you are quite active in other areas of production besides animation photography. Have you ever considered directing an entire film?

R.H.: Oh, yes, I would very much like to direct if I find the right subject. But it’s a big job just to keep track of the special effects. There’s a limit to how much one man can do.

M.C.: Didn’t you once remark that you were unhappy with the animation of the miniature horse in THE VALLEY OF GWANGI? If so, why?

R.H.: No, what I did say was that it was a sequence I ‘dreaded doing because the horse really didn’t have anything dynamic to do. It just had to sit there and look coy. It’s always difficult to decide what to have the creature do in scenes like that. An action sequence involving a giant animal is much more impressive. So I let that scene go until last.

M.C.: Box-office-wise your films have usually done quite well. How can you account for the relative failure of THE VALLEY OF GWANGI?

R.H.: It was released at a time when Warners was being sold and it received very poor distribution. There was no advertising to speak of and nobody knew what the picture was about.

M.C.: Alternately, THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD has really hit big with audiences here.

R.H.: You must remember the time when GWANGI was released. Everyone was on a sex binge then, and we only had sexy dinosaurs. Warners didn’t push the picture at all. Columbia, on the other hand, has put a great deal of effort into their campaign for GOLDEN VOYAGE. That and word-of-mouth really paid off.

M.C.: In the past you have utilized the talents of film composer Bernard Herrmann for your scores. Why was he not used on GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: There were many reasons. Sometimes people are tied up, and sometimes the situation just isn’t conducive to getting the people you would prefer. I think the composer we did use, Miklos Rozsa [SPELLBOUND], writes a different kind of music than Herrmann, and that he did a very good job for us.

R.H.: There were many reasons. Sometimes people are tied up, and sometimes the situation just isn’t conducive to getting the people you would prefer. I think the composer we did use, Miklos Rozsa [SPELLBOUND], writes a different kind of music than Herrmann, and that he did a very good job for us.

M.C.: Taking his past efforts into account, why was Gordon (THE OBLONG BOX) Messier chosen to direct GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: Again, there were many reasons, and I can’t go into them here. I think Hessler has a very good sense of direction. You must remember that the quality of each picture a director works on depends largely on how much money is in the budget. Some people think we have carte blanche to make a picture any way we please. Except for a David Lean or a Stanley Kubrick, this is not the case. We make a commercial product, and though there are many things we might like to do on a picture, it always comes down to whether or not the money is there.

M.C.: All told, how long were you at work on the effects for GOLDEN VOYAGE?

R.H.: About a year. All the work was done here in London at Gold Hock Studios.

M.C.: Did British Museum sculptor Arthur Hayward assist you in constructing the animation models, as he had on ONE MILLION YEARS B.C. and GWANGI?

R.H.: No, I had others assist me. Molding and casting are very time-consuming jobs, so I farm some of it out to certain individual. I can’t do all the models myself, because I don’t have the time.

M.C.: Do you paint your own matte paintings?

M.C.: Do you paint your own matte paintings?

R.H.: No, I don’t. In fact nowadays I try to avoid using them. There are very few people who can do them well enough so that you don’t have to cut away from them right away. Today it’s practically a lost art, unfortunately. Most of the ones in my other films were done by staff matte painters at Shepperton Studios.

M.C.: I found there was quite a bit of grain in GOLDEN VOYAGE. Why was this?

R.H.: We worked with dupes quite a lot. There are shots in the film where you’re looking at a third-generation dupe, so naturally there’s an increase in grain. Another reason you might have spotted some excess grain was because we printed several optical zones and dolly shots on the printer.

M.C.: What can you tell me about your next film project?

R.H.: It’s called SINBAD AT THE WORLD’S END, and that’s about all I can say. We have a formal company which releases information to the public, and at the moment I’m not at liberty to say anything more. Does that pacify you? (Laughs)

M.C.: Not really. Will John Philip Law again play Sinbad?

R.H.: That depends on his availability, and the characterization in the script, which we don’t even have yet. There have been several Sinbads—Douglas Fairbanks, Kerwin Mathews, Guy Williams. We would like to give him a different quality each time. The irony is that when you knock yourself out to make a picture different, the critics chastise you for not putting in the expected cliches. One reviewer said of GOLDEN VOYAGE that he missed the dancing girls. Now that is a typical Arabian Nights cliche that we avoided on purpose.

M.C.: I have one final question concerning THE SEVENTH VOYAGE OF SINBAD. There is a sequence in that film which depicts Sinbad’s crew walking up the beach loaded down with fruit. There is a black man in the crew, and he’s carrying a watermelon.

R.H.: Oh no…(torrents of laughter at this) only a member of today’s generation would notice something like that. I assure you it was all accidental as to who got what prop.

Thus satisfied that THE 7th VOYAGE OF SINBAD contained no racist undertones, I bid Mr. Harryhausen a fond farewell, leaving his Kensington High Street home for the bleak and foggy streets of London. As I ambled towards the nearest Underground I gave additional thought to the question of Mr. Harryhausen’s responsibility for the over-all quality of his films. Approached on an adult level they are rather silly entertainments. But for a child they create a vivid fantasy world where skeletons come to life and fire-breathing dragons battle with cyclops. I was a child once, and the marvels of Harryhausens monsters, both mythic and imaginary, overwhelmed me. There is a definite place in cinema for this type of film. The adult critical eye must squint a bit to watch THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD, but if that’s not enough, one can always leave the theatre to the little people, whose eyes Ray Harryhausen’s films are created for.

PROGRAM:

PROGRAM: