Articles on Animation 04 Dec 2008 08:48 am

Kurtz & Stott

- Last Saturday I featured a “Close Up” article from Millimeter Magazine circa 1976 which showcased two NY producers. To be fair, I’d like to post these two portraits of LA producers also featured in Millimeter.

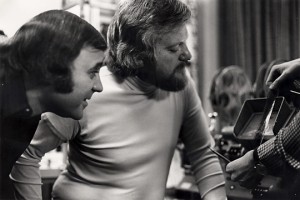

BOB KURTZ

Bob Kurtz, of L.A.’s Kurtz and Friends, is clearly one of the brightest stars in the animation firmament. Bob, a slim, beared fellow with an elfish face and flashing eyes, operates out of 18 compact rooms housed in two charming bungalows enclosed in a small, idyllic courtyard just seconds from the noise and commotion of Hollywood Boulevard. 1728 Whitley Court used to be a private residence, but Bob and his “Friends” have put the bungalows to excellent use: the shelves of the large kitchen cupboard are stocked with jars of cartoon color paint; the living room is now a most handsome reception area and the second-floor master bedroom has been magically transformed into a cozy, intimate projection/screening space.

Bob Kurtz, of L.A.’s Kurtz and Friends, is clearly one of the brightest stars in the animation firmament. Bob, a slim, beared fellow with an elfish face and flashing eyes, operates out of 18 compact rooms housed in two charming bungalows enclosed in a small, idyllic courtyard just seconds from the noise and commotion of Hollywood Boulevard. 1728 Whitley Court used to be a private residence, but Bob and his “Friends” have put the bungalows to excellent use: the shelves of the large kitchen cupboard are stocked with jars of cartoon color paint; the living room is now a most handsome reception area and the second-floor master bedroom has been magically transformed into a cozy, intimate projection/screening space.

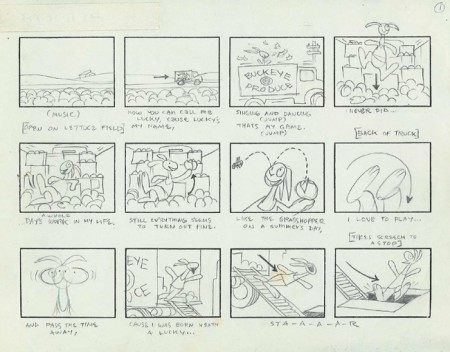

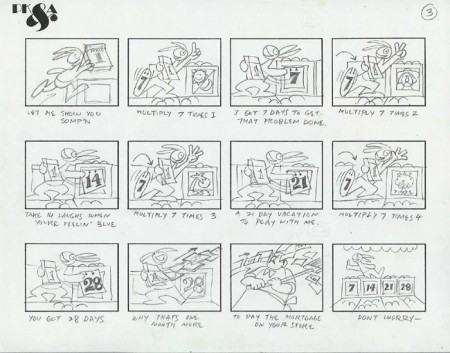

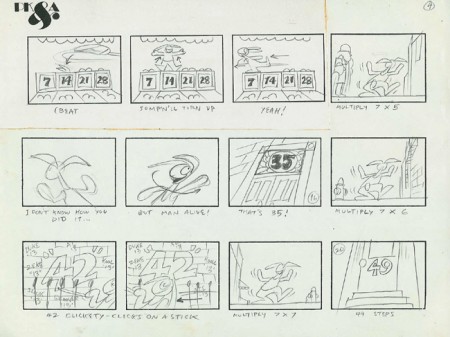

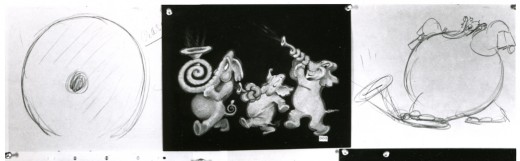

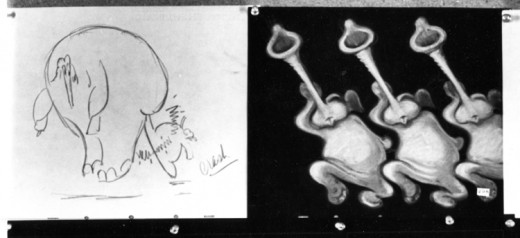

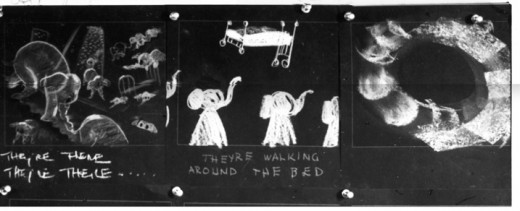

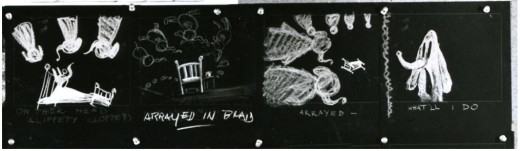

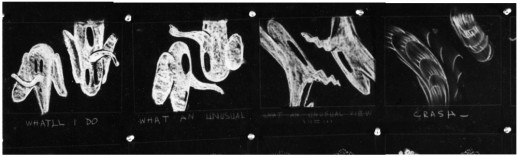

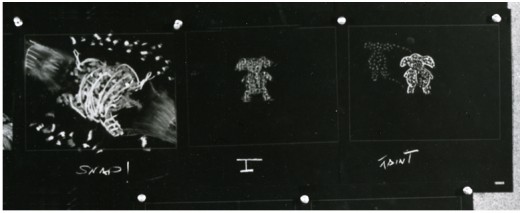

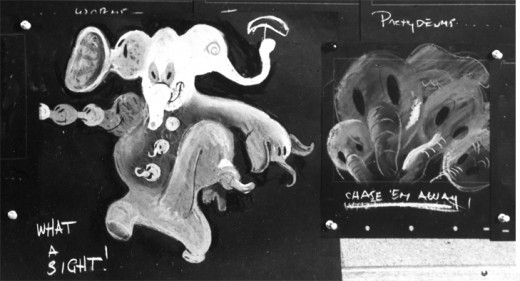

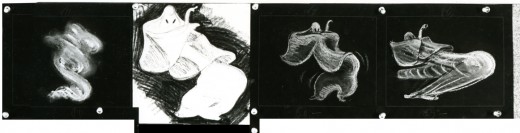

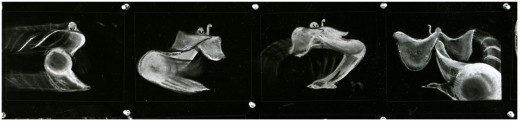

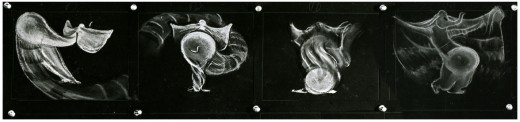

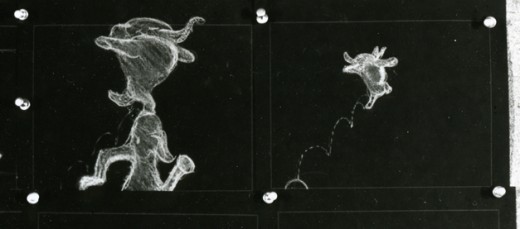

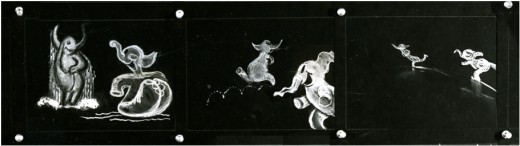

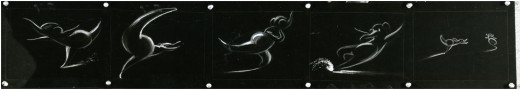

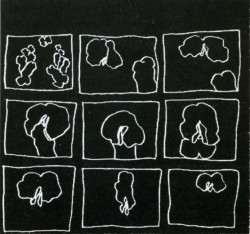

It is here that Bob shows us his sample reel. “The sample reel is what enables—or denies—the animator the opportunity to get work; it’s his resume and must be continually updated and kept current.” Bob’s fertile imagination and liquid creativity are showcased vividly in spots for Levi Strauss, Chevron, Seven-Up, Log Cabin and Sunbeam. (The latter spot won a Clio in 1972 and was shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art as part of an “Art in Advertising” exhibition).

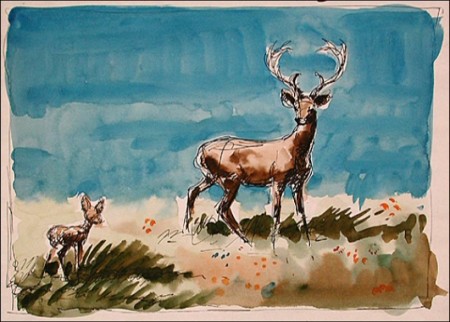

Bob’s art school background and his year as a trainee writer/director at the Walt Disney Studios are distinctly evident in the accomplished agility and precision of his work. A graduate of Los Angeles’ celebrated Chouinard Art Institute (now, sadly, defunct, but once considered – the “Cooper Union of the West”), Bob, in his sparkling, inventive brush strokes and consummate pencil drawing, displays the results of his long years of intense, dedicated art studies. After his stint with Disney, he returned to teach at his alma mater for two years before striking out on his own. He is still, however, very much involved with education: every year he hires a recent art school graduate for on-the-job training and “pencil testing,” as he jokingly calls it, at Kurtz and Friends.

Bob and his wife, Glenna, (who is also his producer) feel very strongly that new blood and fresh ideas should be continually channeled into the company to keep the output brisk and vigorous. Also, they want to try to eliminate as many bureaucratic roadblocks and union restrictions as possible in order to provide an opportunity for young people to get started in the animation business. “I’m trying to create the kind of atmosphere for these kids that I know I would have wanted and needed when I was first starting out.”

Bob and his wife, Glenna, (who is also his producer) feel very strongly that new blood and fresh ideas should be continually channeled into the company to keep the output brisk and vigorous. Also, they want to try to eliminate as many bureaucratic roadblocks and union restrictions as possible in order to provide an opportunity for young people to get started in the animation business. “I’m trying to create the kind of atmosphere for these kids that I know I would have wanted and needed when I was first starting out.”

Of course that means that the young trainees must be willing to work the same kind of endless, grueling hours that are regularly put in by Bob, Glenna, Bob Peluce (Kurtz and Friends’ designer) and the other eleven staff members. “What I’m really offering these trainees,” Bob explains with a mischievious grin, “is the chance to work their asses off . . . but, you know, that’s the best kind of training they can get.”

Kurtz and Friends has always worked exclusively in animation—does Bob foresee the possibility of any live-action shooting in the near future? “No, I really don’t think so,” he answers without hesitation. “In live-action there is just too much that is uncontrollable and time-wasting. Things like negotiating to get the talent, trying to make an animal “act,” ego trips by people involved—all of that can distract you from your real work: telling a short but memorable story. Animation, compared to live-action, is pure and clean. After all, in animation you’re only limited by your imagination.”

After a couple of hours with Bob at Kurtz and Friends we can assure you that ole Mr. Imagination is alive and kickin’ at 1728 Whitley Court, in the heart of Hollywood.

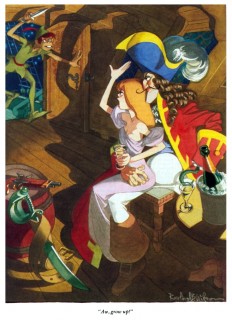

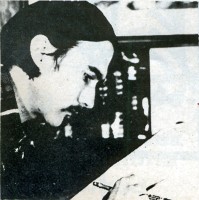

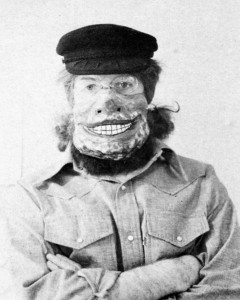

HERB STOTT

The offices of Herb Stott’s Spungbug-gy Works are located at perhaps the most glamorous spot in all Los Angeles, the corner of Sunset Boulevard and La Cienega, not more than a stone’s throw from Dino’s Lodge, for all you 77 Sunset Strip devotees and just a hop, skip and a jump from The Source, L.A.’s best organic restaurant, for all you health food nuts. Herb is a bearded, sandy-haired fellow of 42 who looks more like a trim, fit 32. He began his career at Disney Studios in the early Fifties; after a stint in the service he did some L.A. free-lancing before forming Spungbuggy in 1963. For the first ten years it was all animation for the company but within the last three years Herb has branched out into live-action. Now it’s 50-50: the Spungbuggy staff does animation under the capable leadership of Animation Directors Gary Katona and Randy Akers and Herb himself shoots the live-action spots. Despite this Herb still considers animation his metier and first love. He remembers his early, formative years at Disney with great affection: “Working there was like going to a small, rural liberal arts college. (Herb himself attended Ohio State.) There was a sports league comprised of members of the various departments that competed against each other in volleyball, tennis and softball. The employees used to have their lunch all together on the studio lawn, like one big picnic, executives and third assistant editors. There was this amazing camaraderie. Lots of genuine affection and respect, especially for Walt himself. Do you know that the studio has kept Walt’s office exactly as it was the day he died?”

The offices of Herb Stott’s Spungbug-gy Works are located at perhaps the most glamorous spot in all Los Angeles, the corner of Sunset Boulevard and La Cienega, not more than a stone’s throw from Dino’s Lodge, for all you 77 Sunset Strip devotees and just a hop, skip and a jump from The Source, L.A.’s best organic restaurant, for all you health food nuts. Herb is a bearded, sandy-haired fellow of 42 who looks more like a trim, fit 32. He began his career at Disney Studios in the early Fifties; after a stint in the service he did some L.A. free-lancing before forming Spungbuggy in 1963. For the first ten years it was all animation for the company but within the last three years Herb has branched out into live-action. Now it’s 50-50: the Spungbuggy staff does animation under the capable leadership of Animation Directors Gary Katona and Randy Akers and Herb himself shoots the live-action spots. Despite this Herb still considers animation his metier and first love. He remembers his early, formative years at Disney with great affection: “Working there was like going to a small, rural liberal arts college. (Herb himself attended Ohio State.) There was a sports league comprised of members of the various departments that competed against each other in volleyball, tennis and softball. The employees used to have their lunch all together on the studio lawn, like one big picnic, executives and third assistant editors. There was this amazing camaraderie. Lots of genuine affection and respect, especially for Walt himself. Do you know that the studio has kept Walt’s office exactly as it was the day he died?”

While free-lancing Herb also put in time at Hanna-Barbera when they were in their infancy as animators. He loved it there—”Animators are a different breed, they’re far more affable, accessible and sincere than their counterparts in live-action. Perhaps it’s because we’re filled with an awful lot of whimsy. It might also be because ours is a one-on-one business, an animator really depends upon himself and his own imagination. Also there are no star trips or ego problems; animators create their own stars.”

Art school graduates are constantly coming to Spungbuggy seeking jobs, even if it’s only as a “gofer.” “Maybe one out of twenty-five has something special,” Herb reports. “If it’s something truly special I’ll find a spot for them, if not here than hopefully with another animator.” Herb stays in constant touch with his fellow L.A.-based animators and is, in fact, a close friend of Bob Kurtz, who was the subject of a February ’76 Close-Up. Herb is quick to praise and give credit to other practitioners of the art of animation; there seems to be none of the professional jealousy or rabid backbiting that is so commonly found among major Madison Avenue agencies. Perhaps it’s due to all that “whimsy” that Herb was talking about…

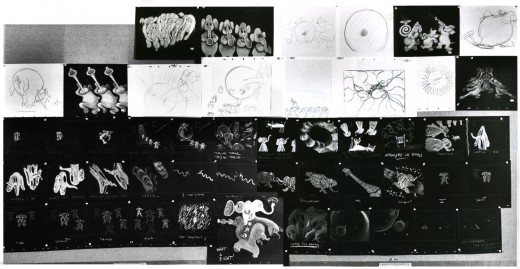

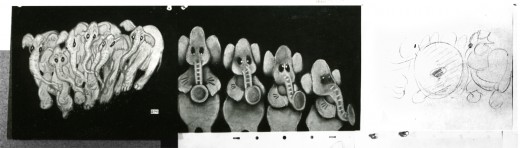

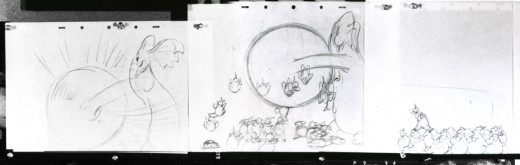

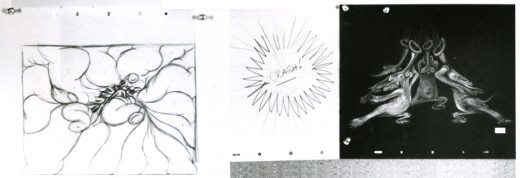

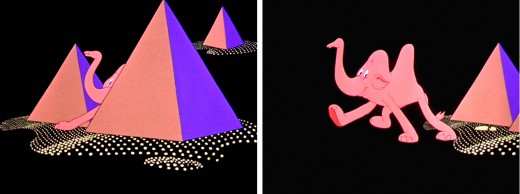

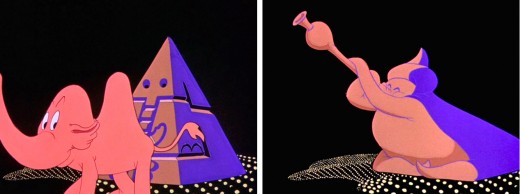

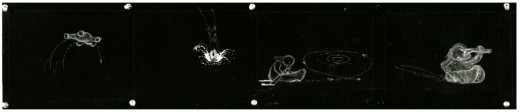

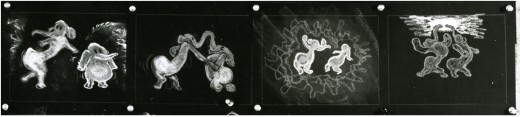

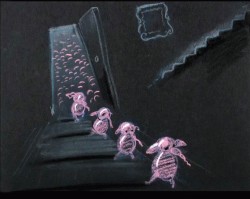

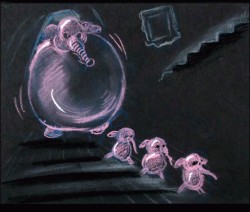

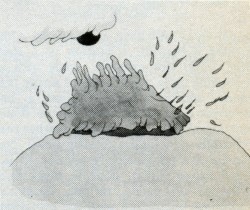

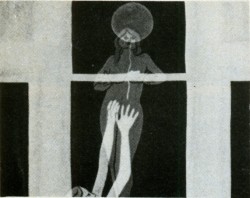

In looking at Herb’s reel one soon realizes that Spungbuggy’s client list reads like a veritable Who’s Who of television commercials. Among the clients represented are Levi-Strauss, Clairol, Raid, Nestle’s, Kellog’s, Mr. Clean and a series of spots for American Cyanimid of which Herb is particularly proud. Among our own personal favorites were a wickedly clever Tootsie Roll spot where a child’s tongue has an argument with his teeth about who gets first taste of the chocolate center, is it better to suck or chew?? And a wildly imaginative Illinois Bell spot extolling the virtues of touch-tone telephoning. This spot, not surprisingly, picked up a Clio in 1972. Perhaps the most visually impressive spot is for United Airlines: an outlandishly animated map of the U.S. complete with geographic landmark caricatures for each distinct section of the country. (Example: Marina Towers in Chicago doing a spirited version of a kind of “skyscraper Hustle.”) It is a vivacious and memorable one minute look at this diverse land of ours; yet it still succeeds most admirably in getting across United’s “friendly skies” message.

Herb’s future plans for Spungbuggy? “Nothing grandiose—I just want to continue the way we’re going. I look forward to another strong, successful year. I’m just grateful that we’re able to stay alive and healthy in such a competitive field.”

Spungbuggy is, indeed, alive and well and thriving in L.A.. Just stop by the corner of Sunset and La Cienega and see for yourself.

The Bob Kurtz article came from Millimeter Magazine, Feb/1976

The Herb Stott article came from Millimeter Magazine, Feb/1977