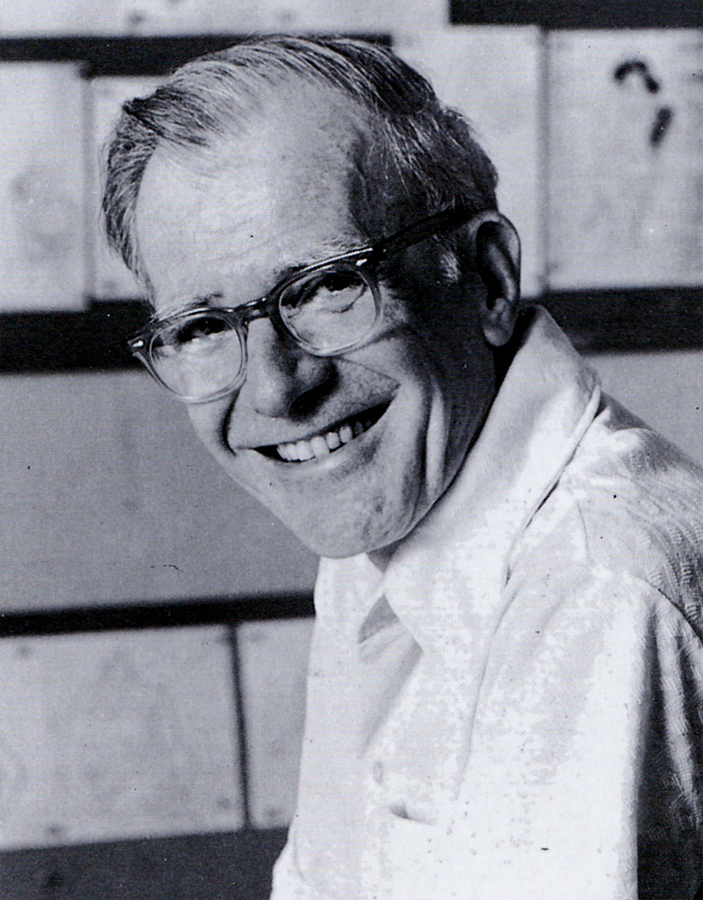

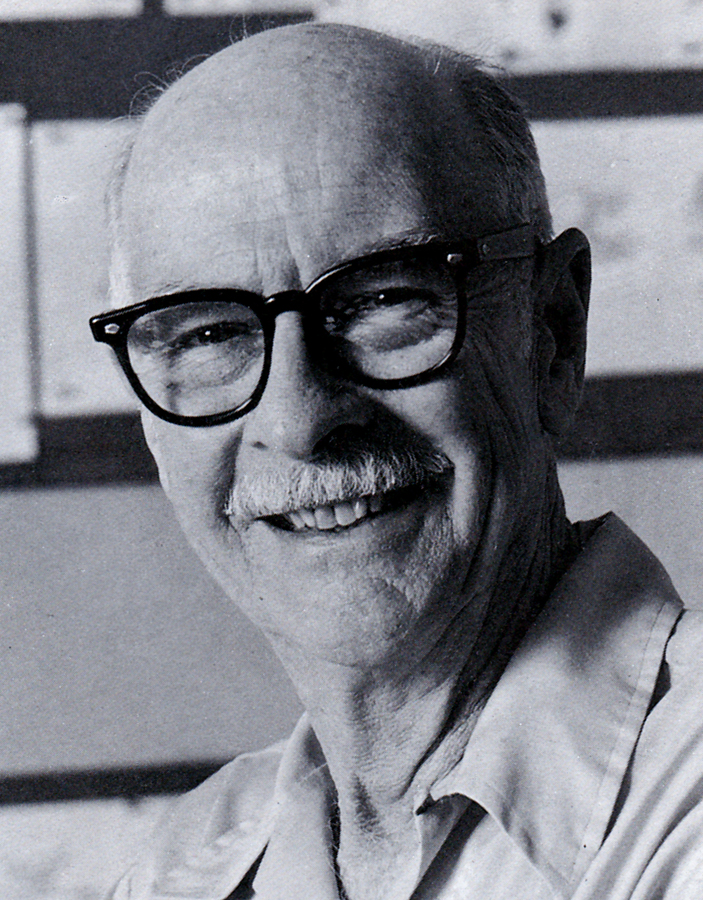

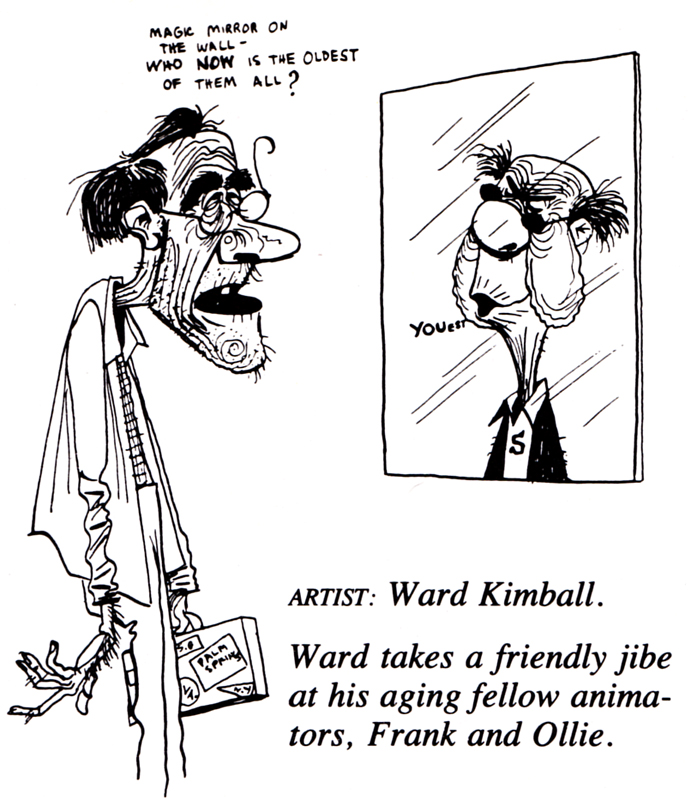

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

- The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston was first published in 1981. The book came out with a large splash and overwhelming acceptance by the animation community. It’s since remained the one bible that animation wannabees turn to as a source of inspiration and an attempt to learn about that business.

I admitted a couple of weeks back that though I must have been one of the very first to have bought the book, I’d never actually read it. I spent hours poring over the many pictures and the extensive captions, but the actual book – I didn’t read it. I can’t say why, but this was my reality.

Then not too long ago, Mike Barrier wrote that he was not a supporter of the book and its theories, I wondered about that writing and decided to reconsider reading it. I knew I had to go back to find out what I’d stupidly ignored, so I started reading.

The book starts out with a lot of history of animation, something routine and expected from the two animators that lived through a good part of the story. As a matter of fact Thomas and Johnston were at the center of the history. It didn’t take long for the animation “how-to” to kick in. For the remainder of the book, using that history, the two master animators explained how and why Disney animation was done, in their opinions. They write about processes and systems set up at Disney during their tenure there. They write about theories and methods of fulfilling those theories. There’s a lot for them to tell and they’ve succinctly organized it into this book, as a sort of guide.

However, at two points they go wildly into a divergent path from the one that they started building. Their methods altered and, to me, seemed to be about the finances of doing the type of animation they did, rather than the reason. Impractical as those original theories were, I’d believed in the myth all those years to start changing now. So I want to review these two stances instead of outwardly reviewing the book. Besides it’s too long since the book has stood in its own royal space for me to pretend that I could properly review it.

The growth of animators at the Disney studio relied on a system wherein each of the better animators was assigned one character. Unless there was a minimal action by some external character, the one animator ruled over the character.

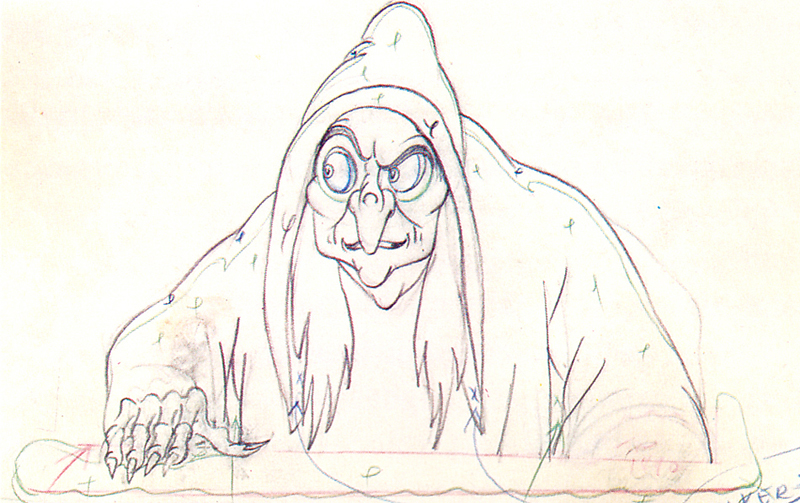

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

- Bill Tytla did Stromboli in Pinocchio. He did principal scenes of Dumbo in that film. He handled the Devil in Fantasia (as well as all his twisted mignons within those scenes.) Tytla worked on the seven dwarfs but was the principal animator of Grumpy.

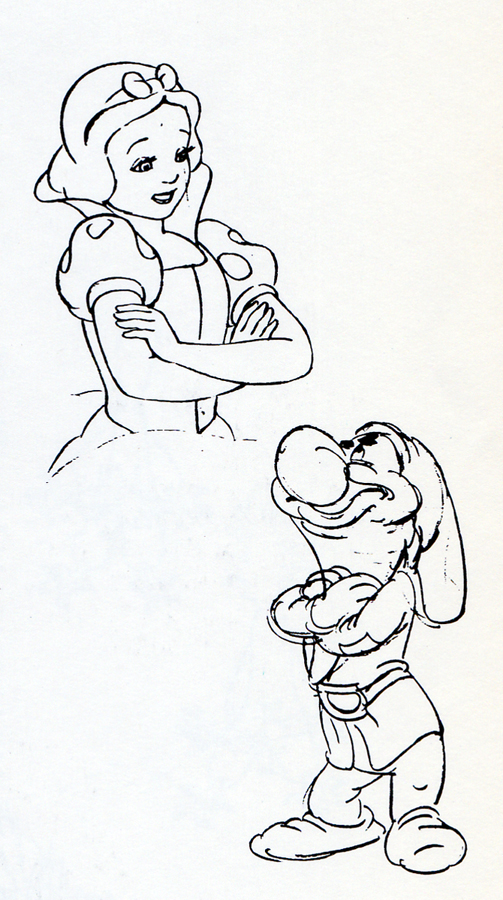

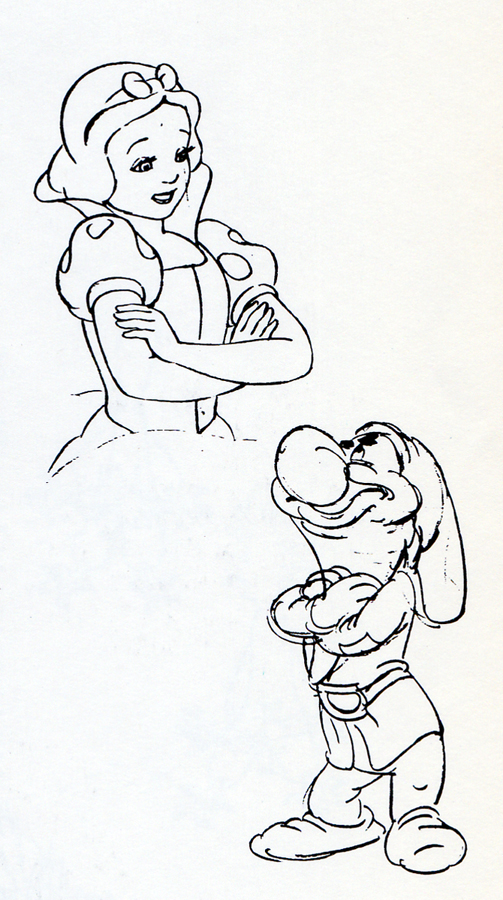

- Fred Moore also did the dwarfs in Snow White but seemed to focus on Dopey. He did Lampwick in Pinocchio and Mickey in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

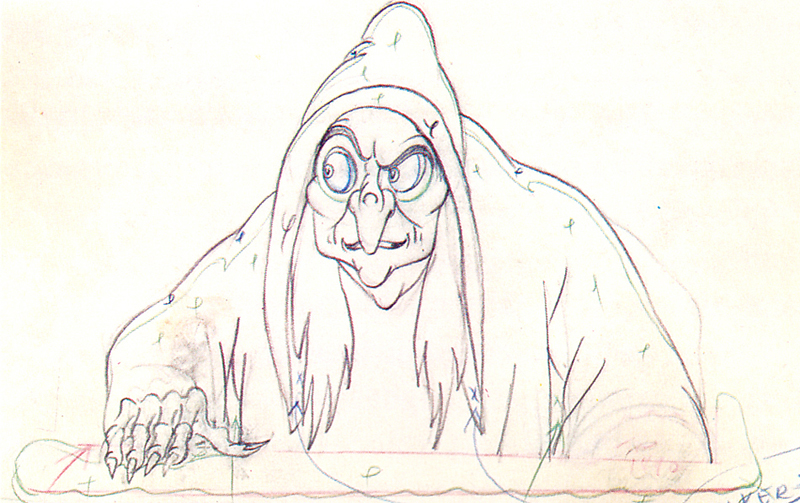

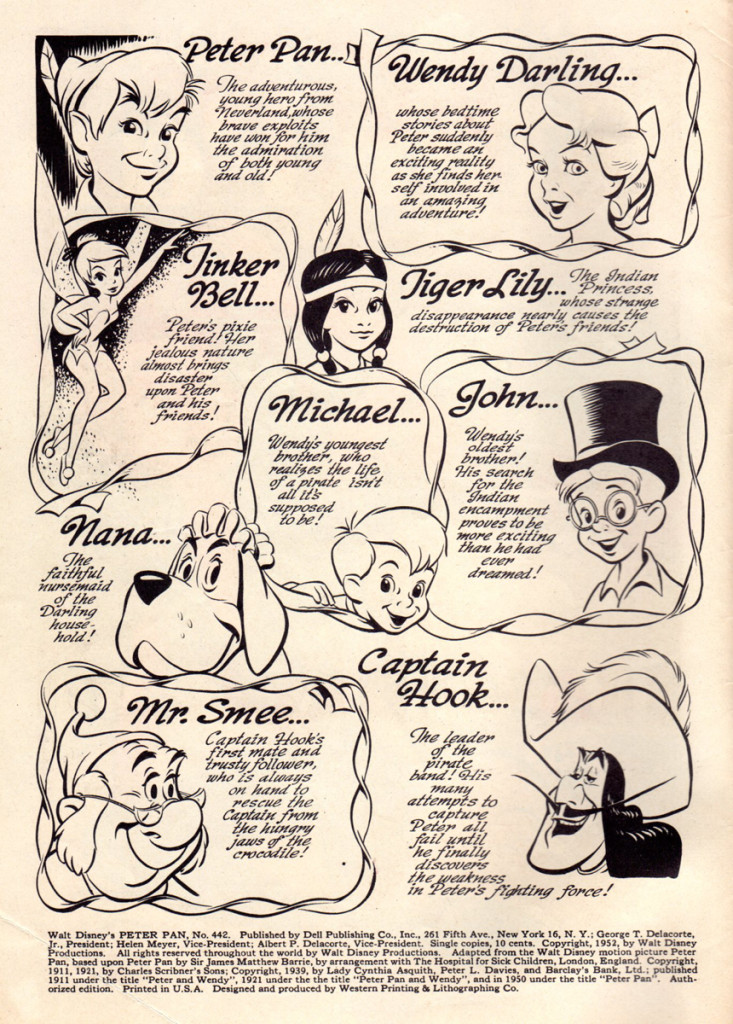

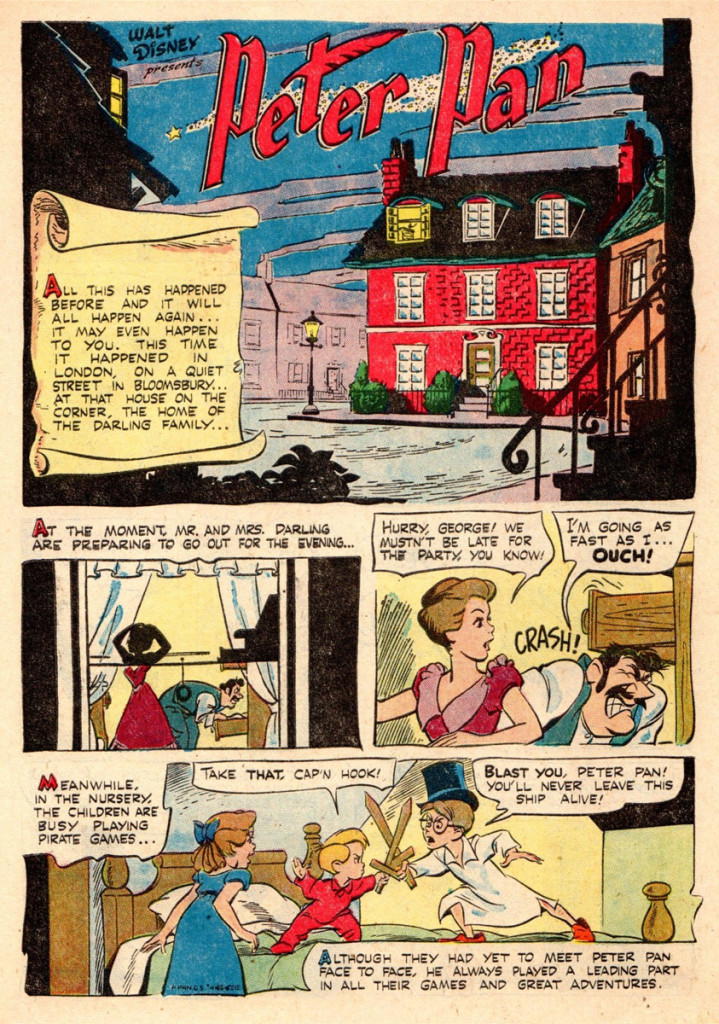

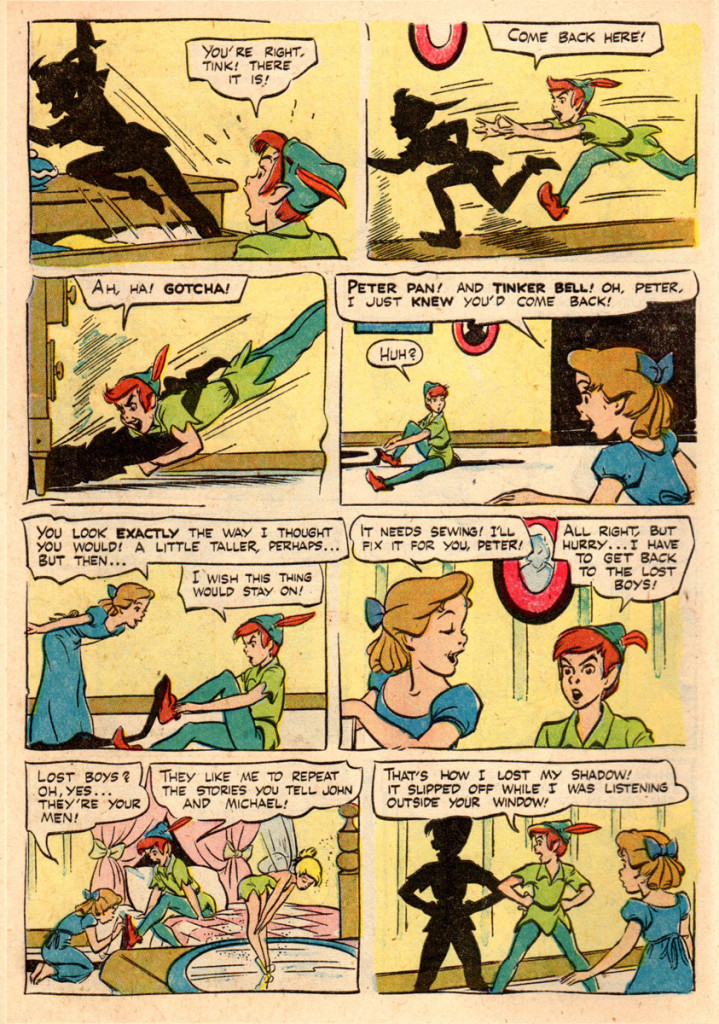

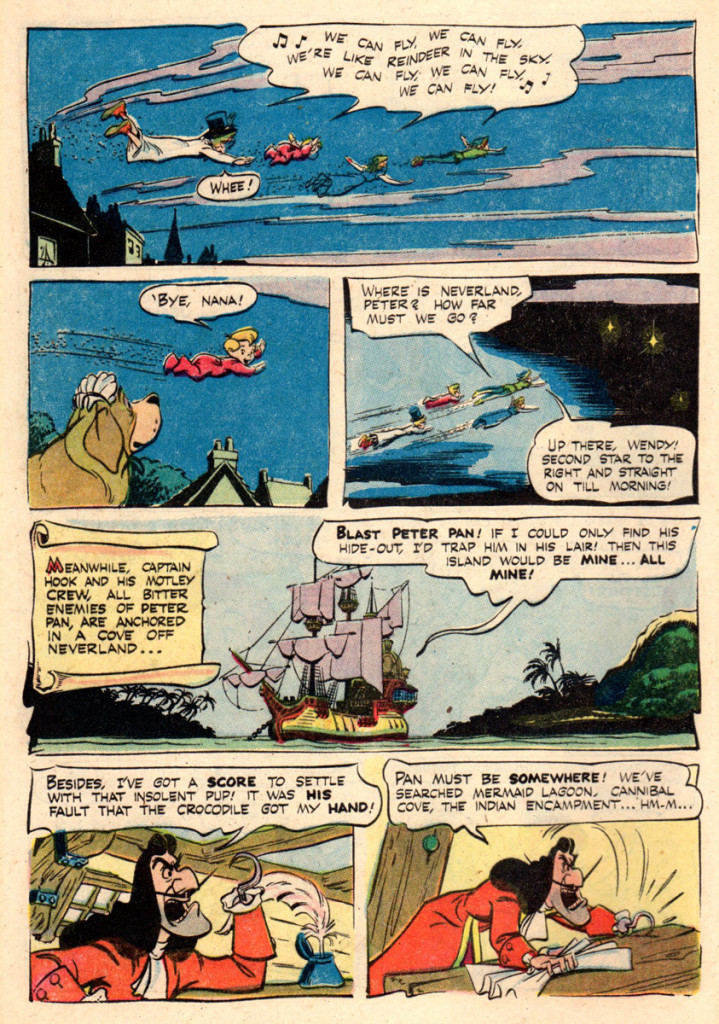

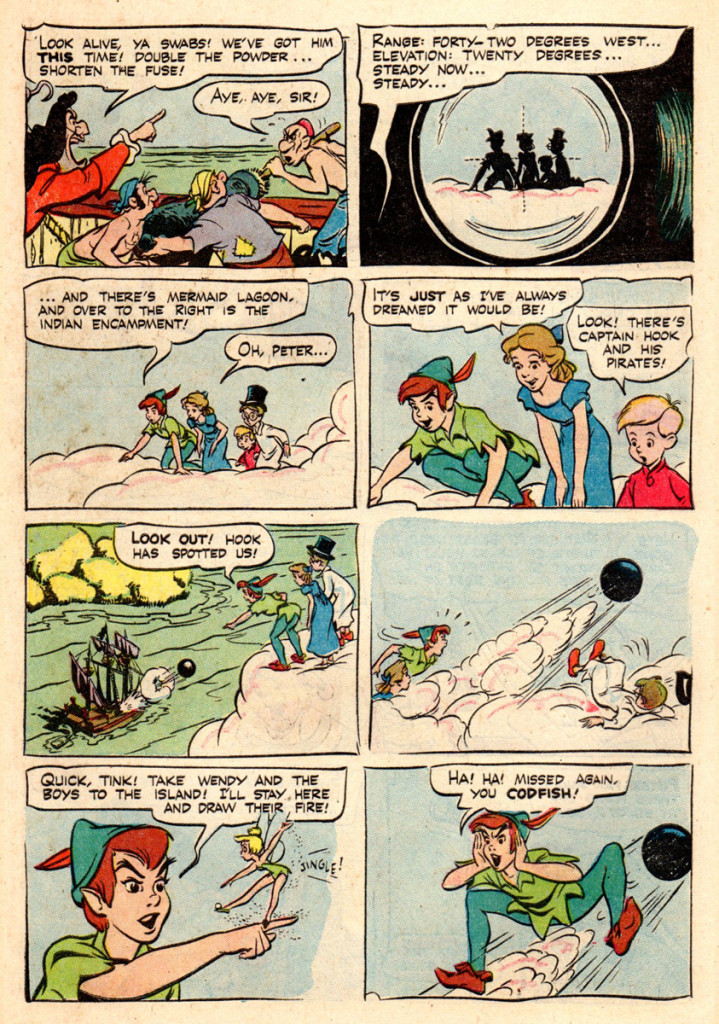

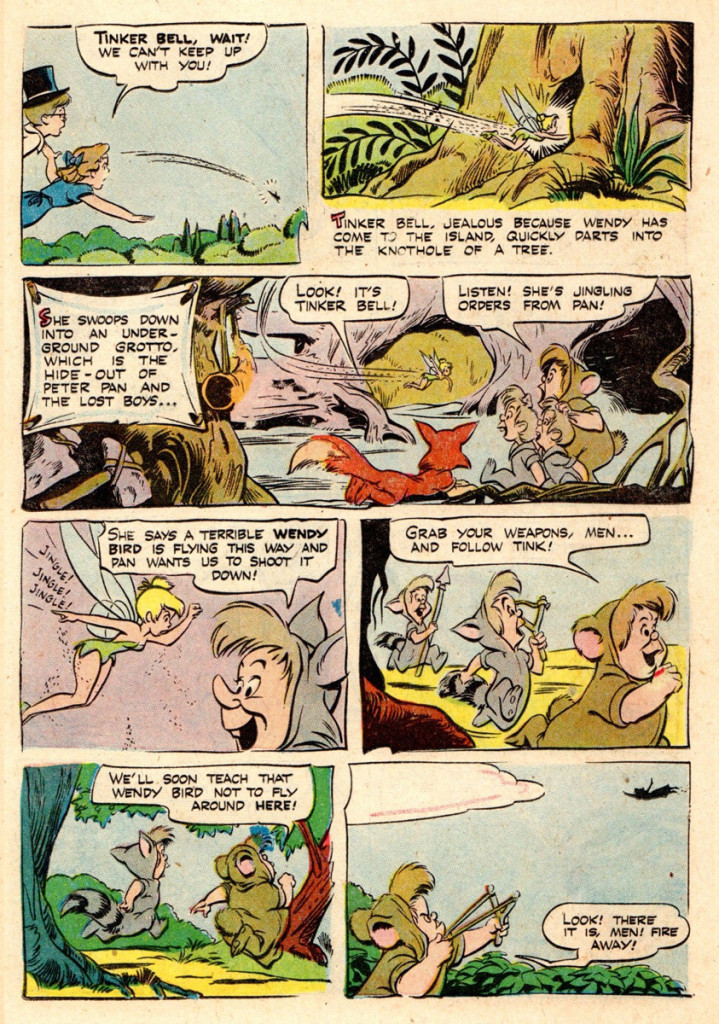

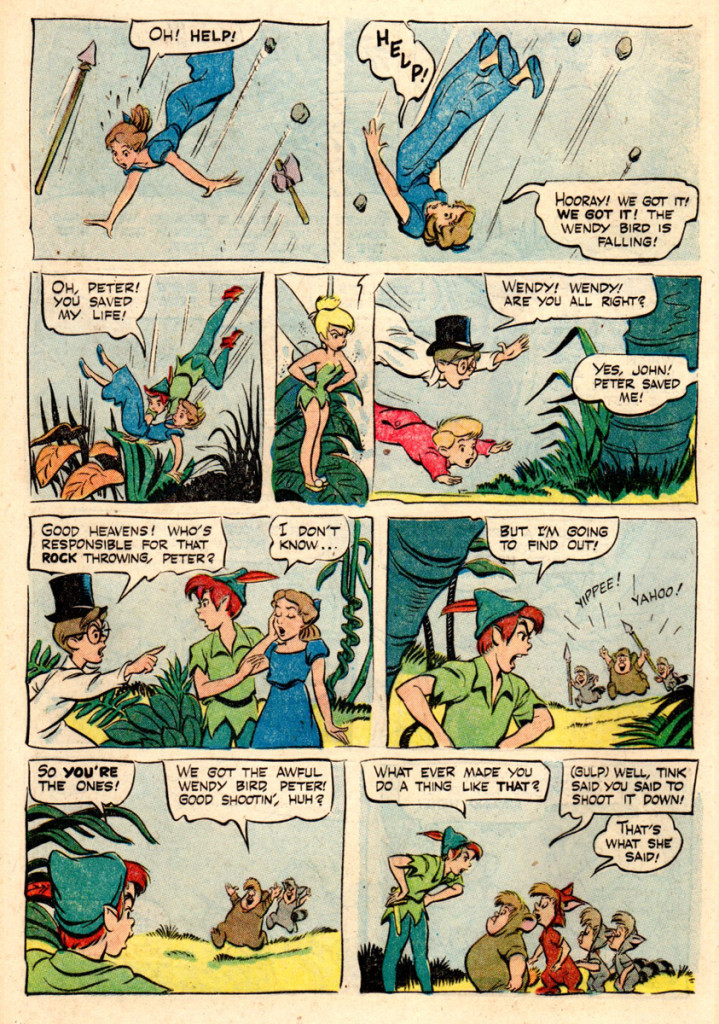

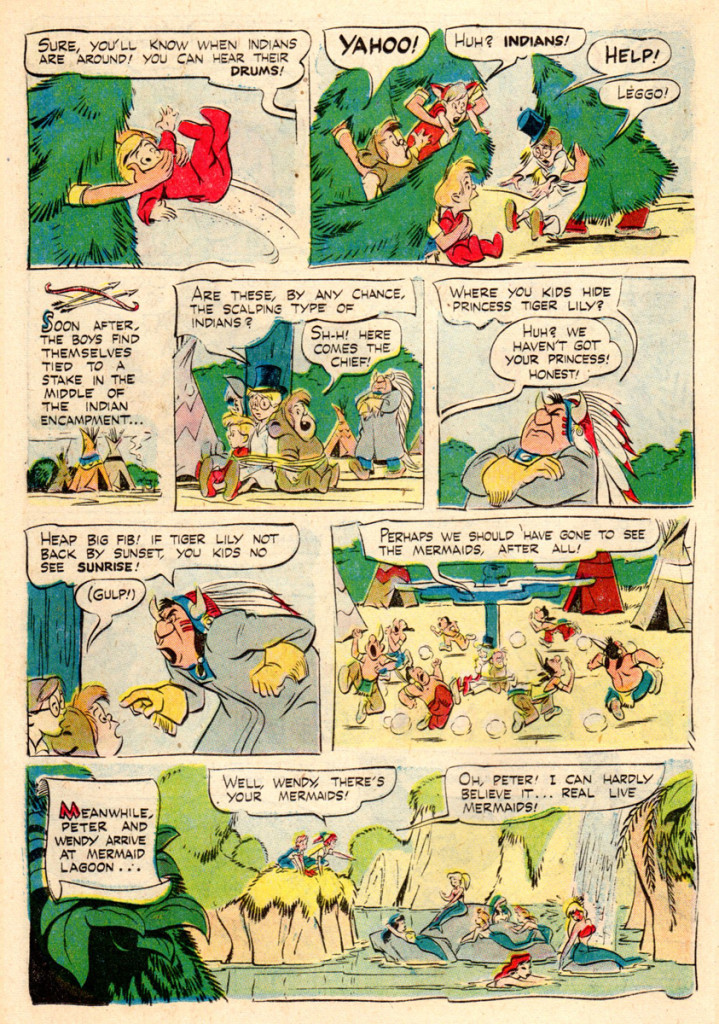

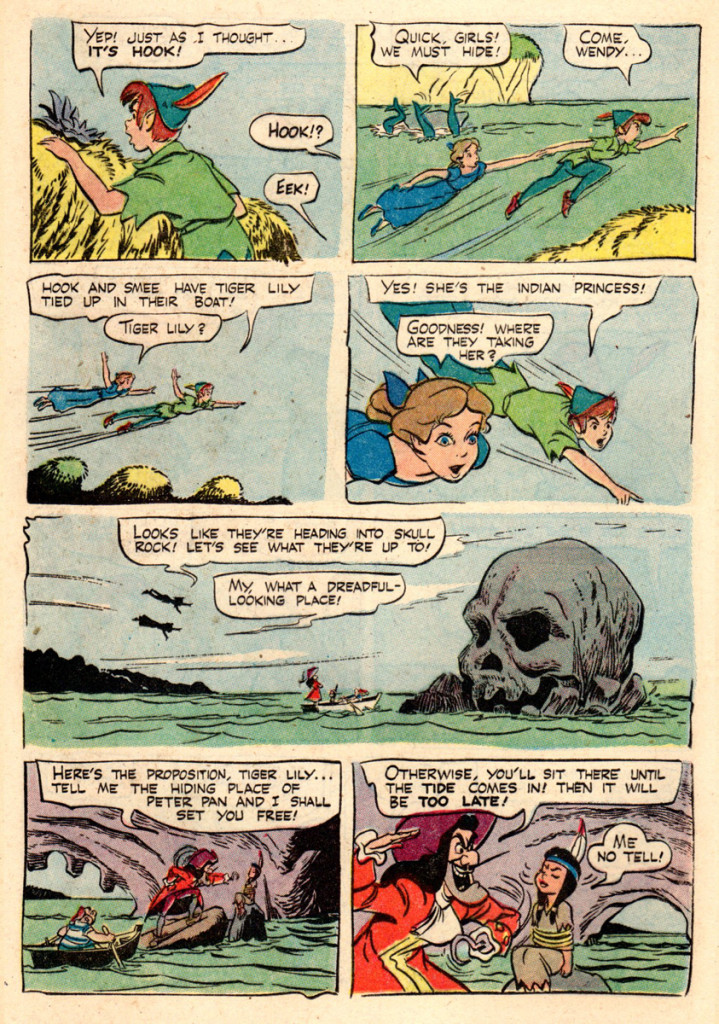

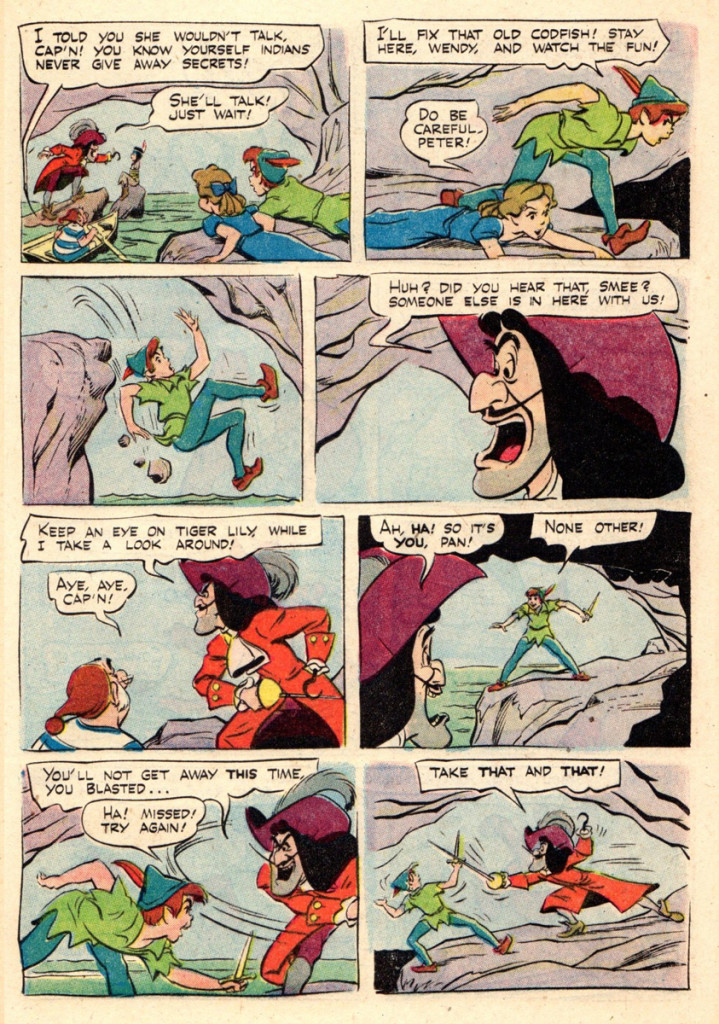

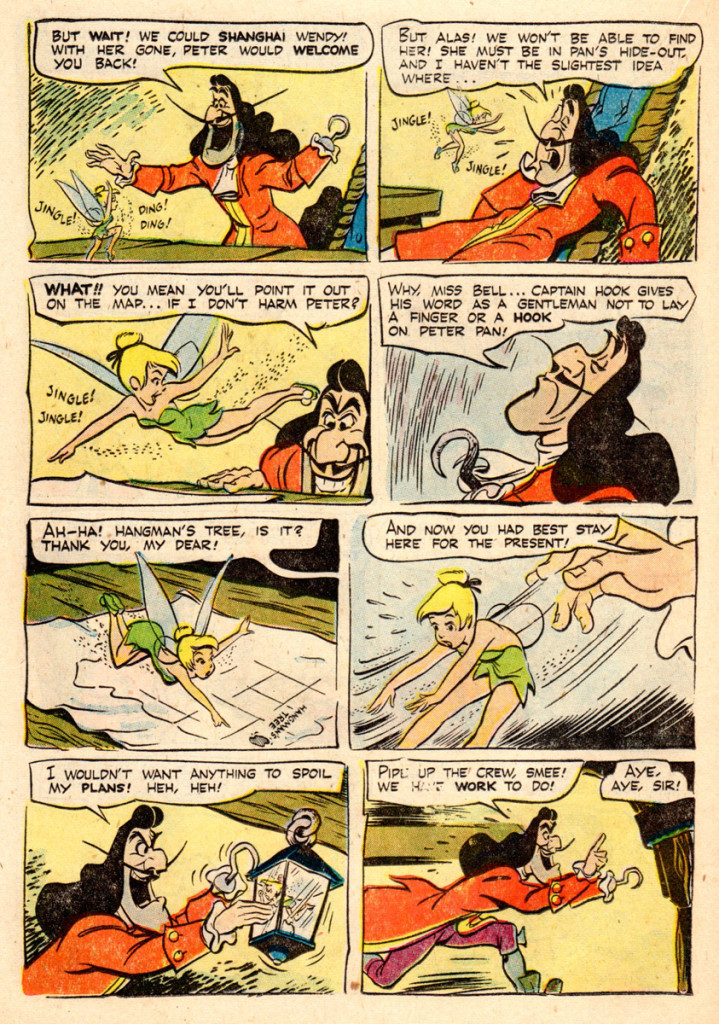

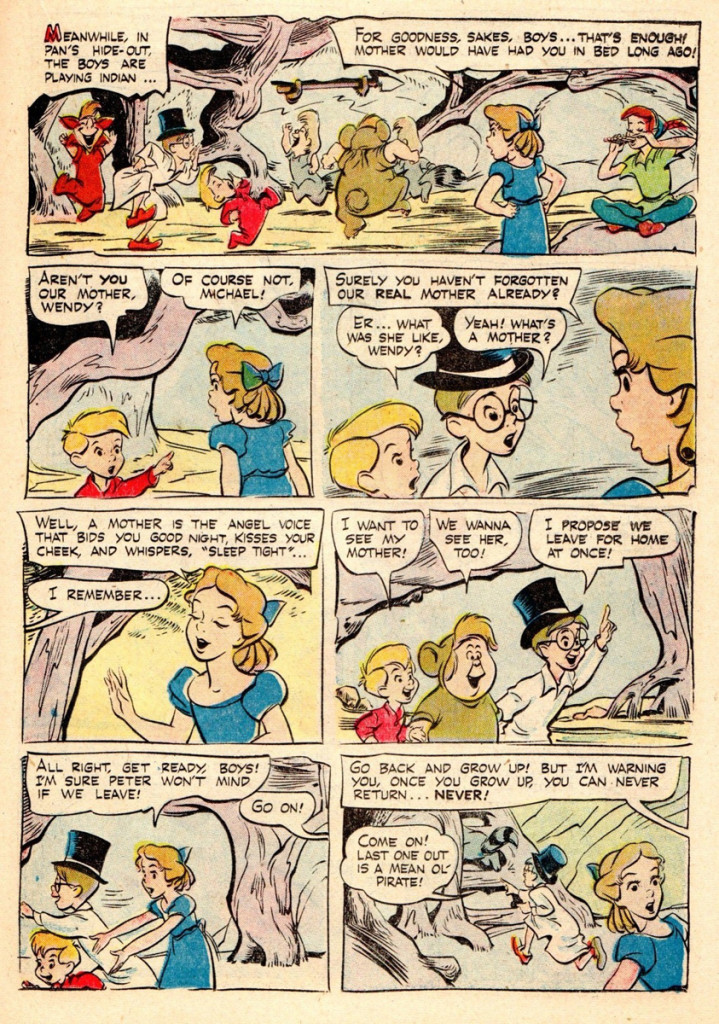

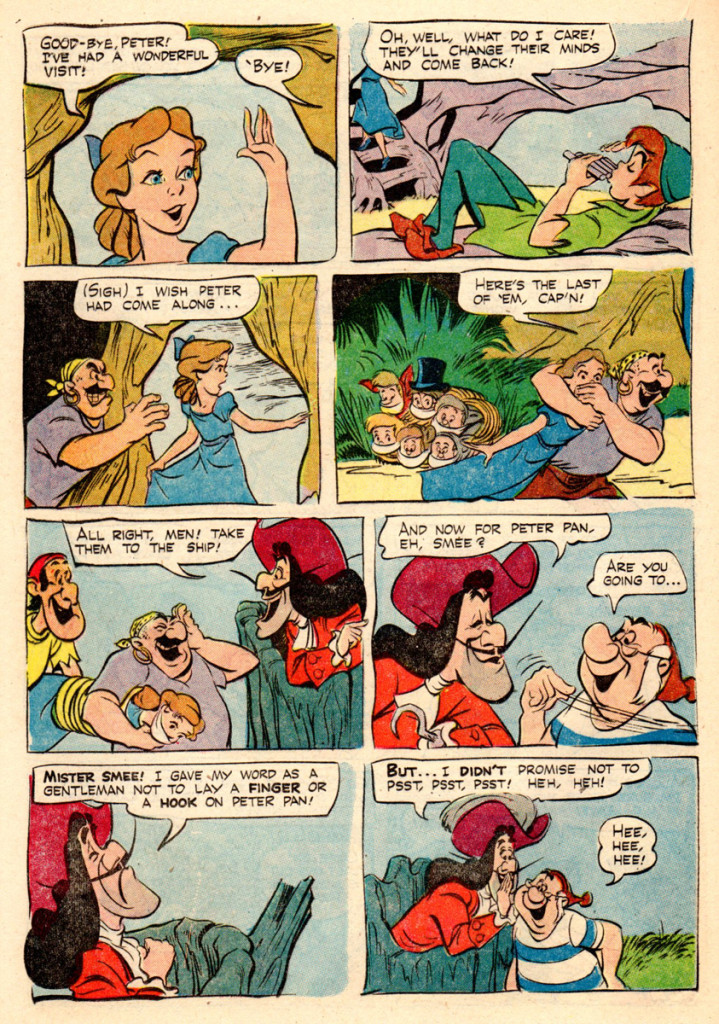

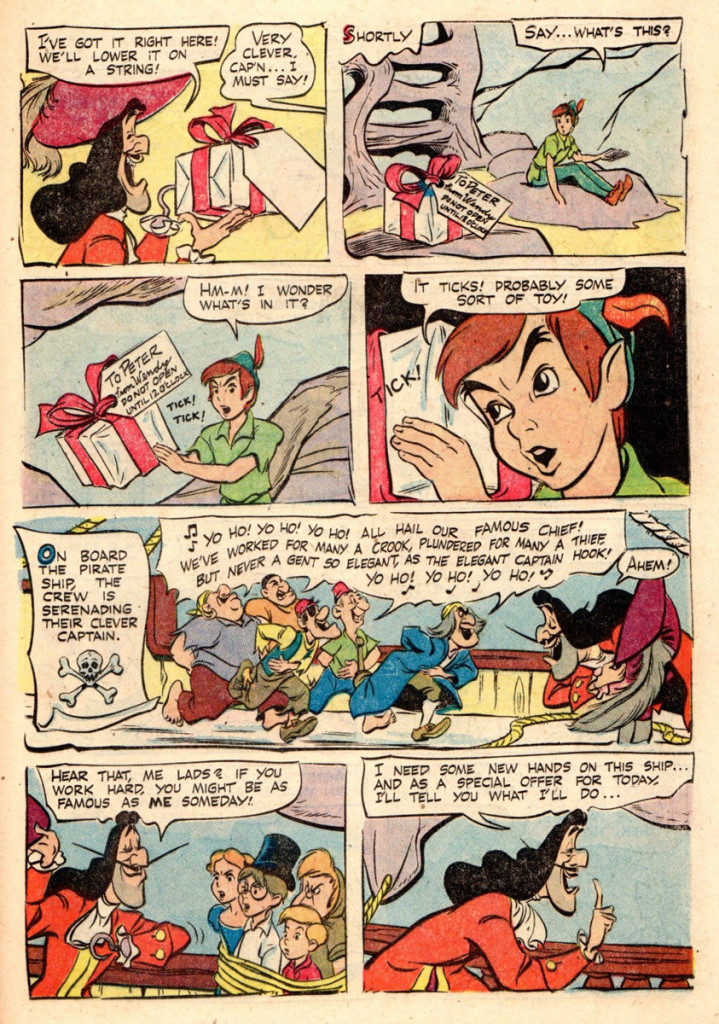

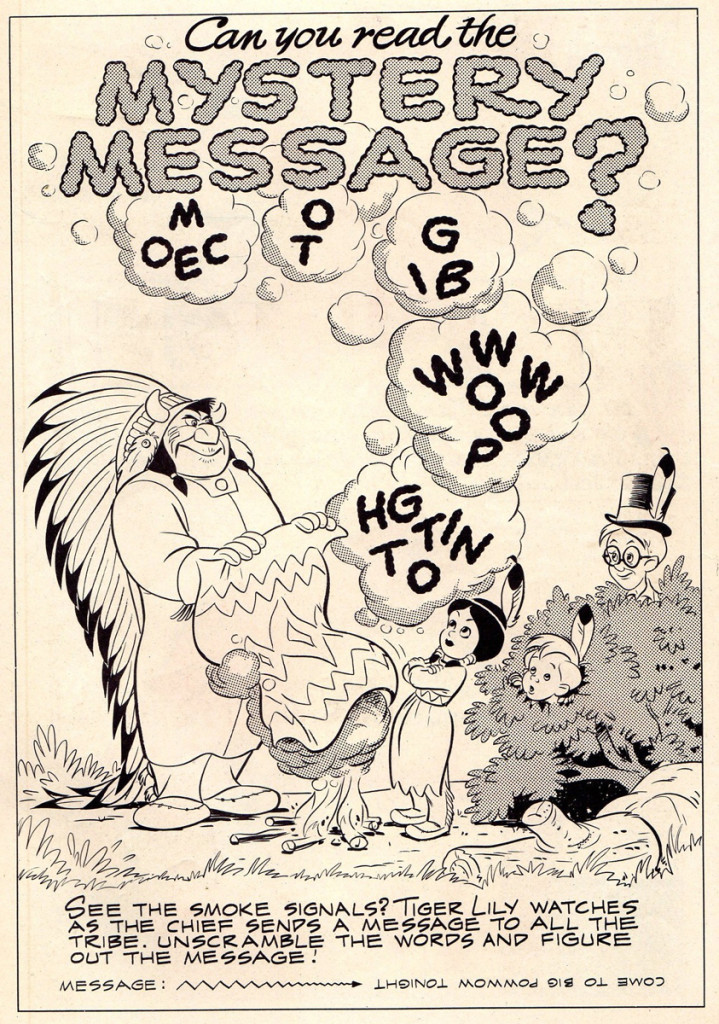

- Marc Davis started as an assistant under Grim Natwick on Snow White. He became the Principal artist behind Bambi, the young deer. He did Alice in Alice in Wonderland, Tinkerbell in Peter Pan, Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty and Cruella de Ville in 101 Dalmatians.

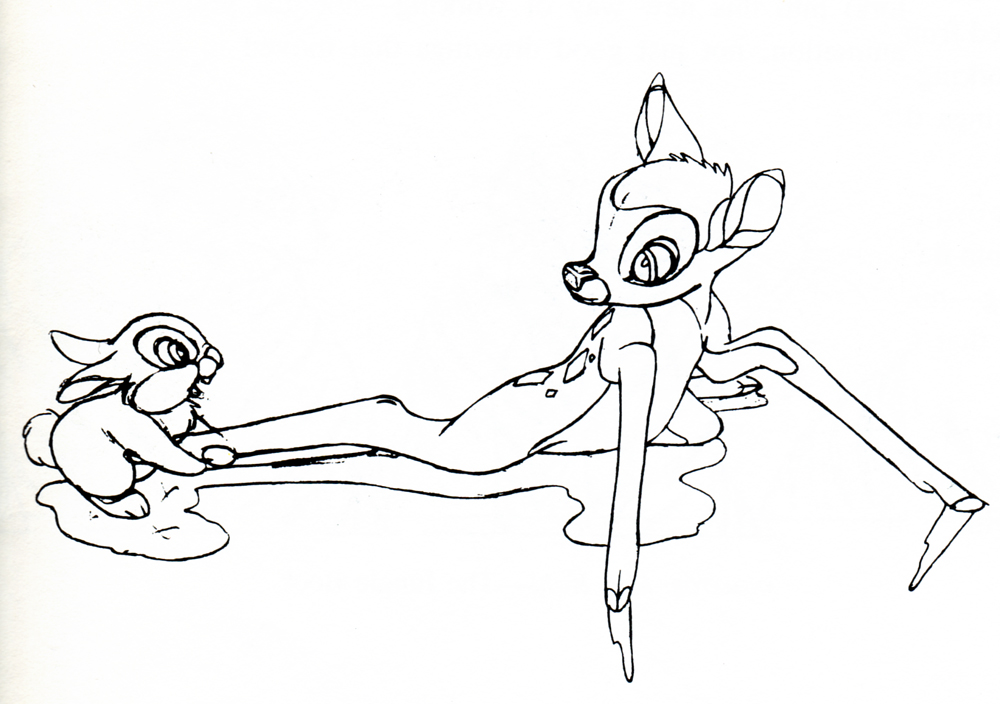

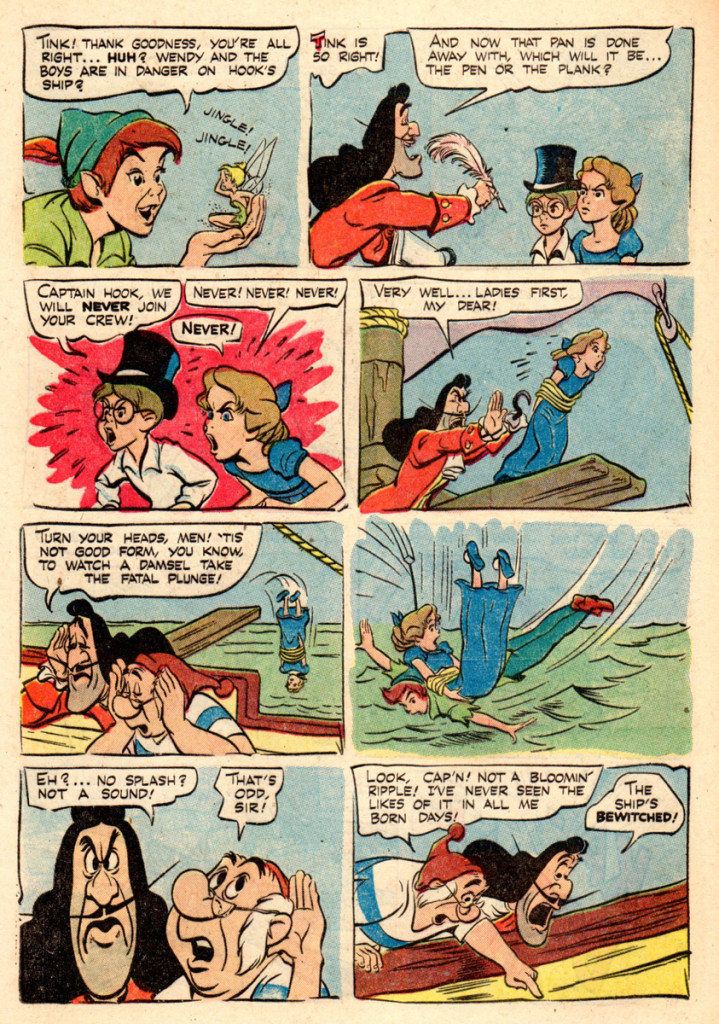

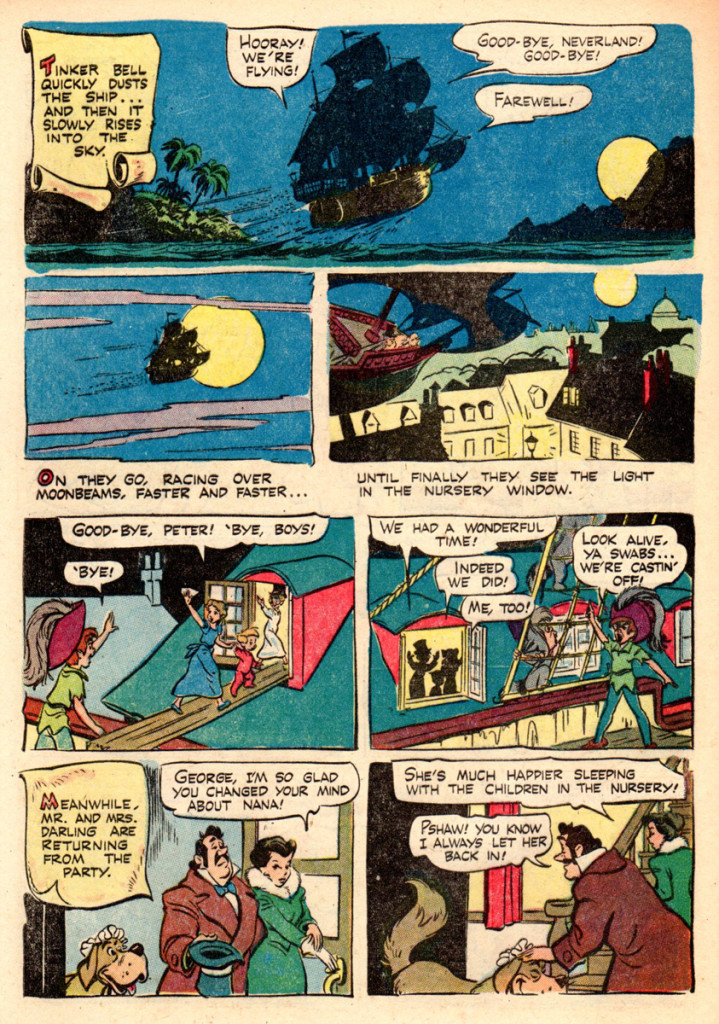

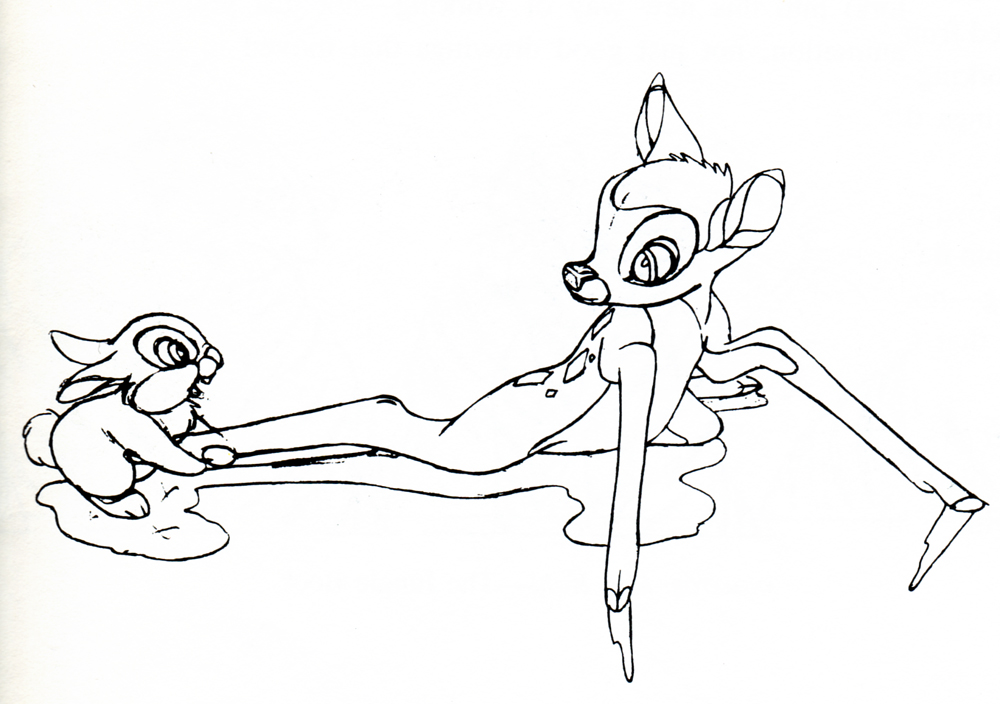

- Frank Thomas did Captain Hook in Peter Pan, the wicked Stepmother in Cinderella, Bambi and Thumper on the ice in Bambi.

- Ham Luske and Grim Natwick did Snow White. The two sides of her personality came about because of conflicts between the two animators. This was a way for Walt to complicate Snow White’s character; he employed two animators with different strong opinions about her movement. By putting Ham Luske in charge, he was sure to keep the virginal side of Snow White at the top, but by having Natwick create the darker sides of the character, Disney created something complex.

Many animators fell under these leaders’ supervision and tutelage, also working on one principal character in each film. This system was something they swore by and broadcast as their way of working at the studio. It would allow the individual characters to maintain their personalities as one animator led the way.

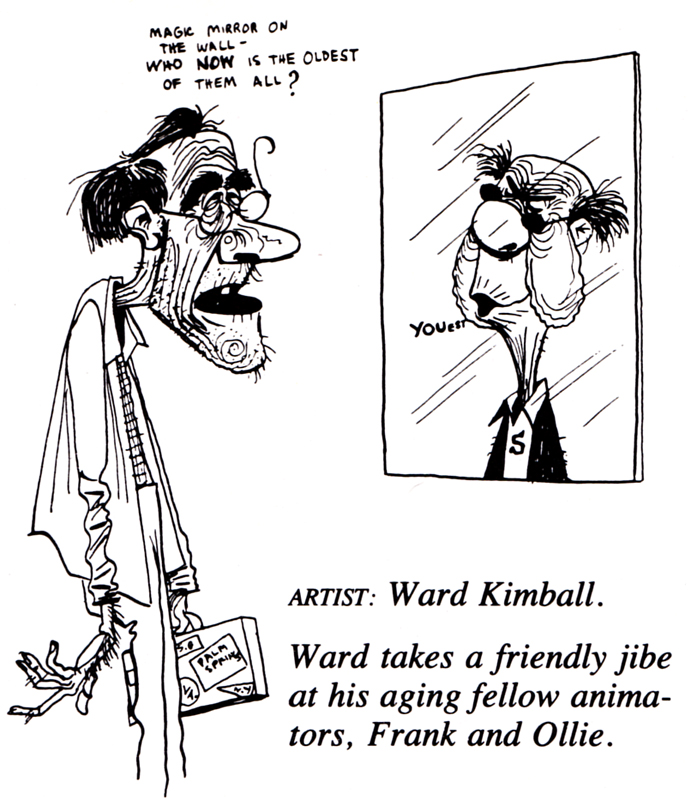

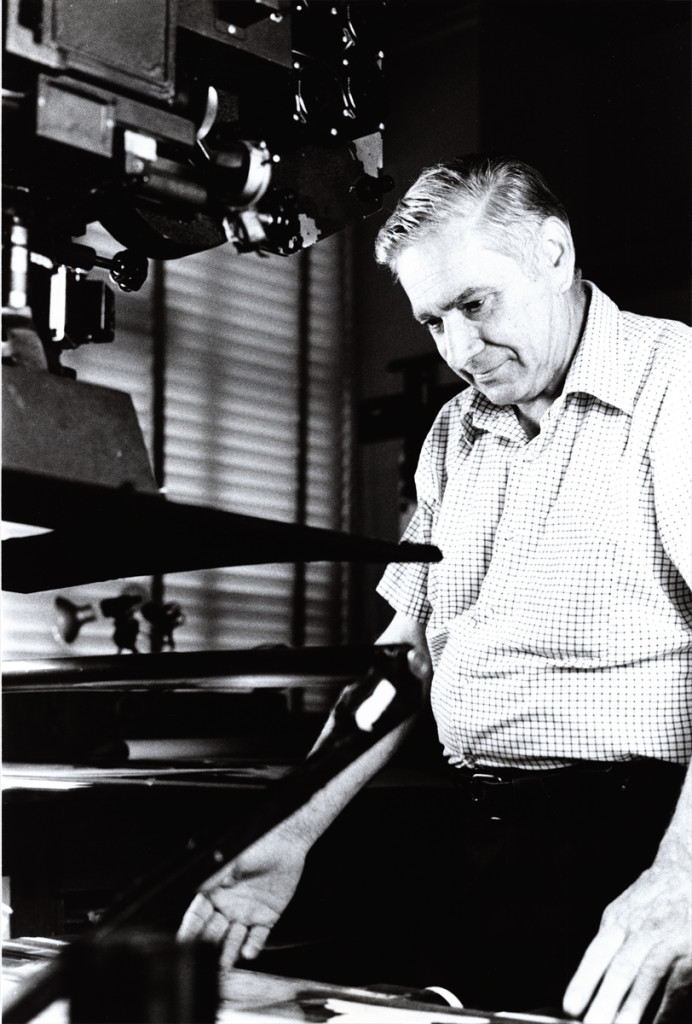

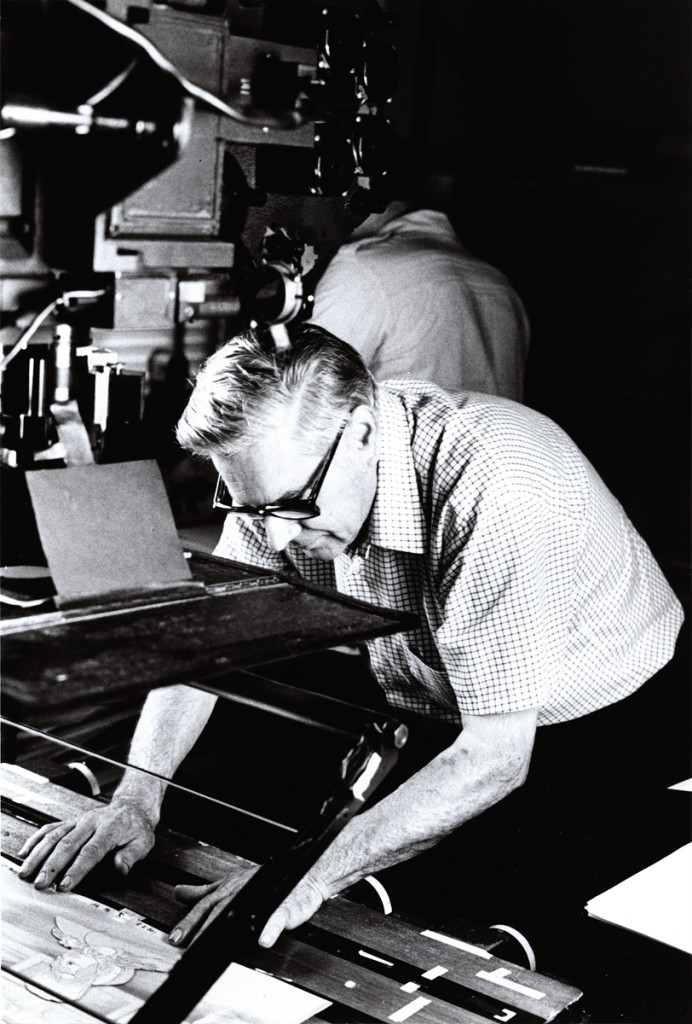

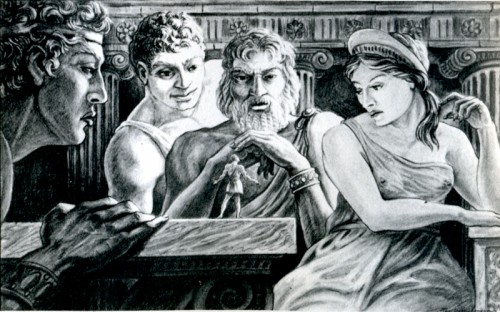

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

But as Walt grew more involved with his theme park and his television show and the live action movies that were doing well for the studio, things changed at the animation wing of the studio. It became clear, with the over budgeted spending on Sleeping Beauty and the new demands for a different look once xerography entered the picture in 1959. The rhythm and personality of the productions changed, and their methods of animation changed. Walt also sorted out nine loyalists to be his “Nine Old Men” thus dividing the animators into groups, a hurtful way of setting up competition among the animators. ________________________Kahl, Davis, Thomas, Walt, Jackson, Johnston seated

Thomas and Johnston get to justify this

in their book.

Let me read a section from the book to you:

“Under this leadership, a new and very significant method of casting the animators evolved: an animator was to animate all the characters in his scene. In the first features, a different animator had handled each character. Under that system even with everyone cooperating, the possibilities of getting maximum entertainment out of a scene were remote at best. The first man to animate on the scene usually had the lead character, and the second animator often had to animate to something he could not feel or quite understand. Of necessity, the director was the arbitrator, but certain of the decisions and compromises were sure to make the job more difficult for at least one of the animators.

“The new casting overcame many problems and, more important, produced a major advancement in cartoon entertainment: the character relationship. With one man now animating ever character in his scene, he could feel all the vibrations and subtle nuances between his characters. No longer restricted by what someone else did, he was free to try out his own ideas of how his characters felt about each other. Animators became more observant of human behavior and built on relationships they saw around them every day.”

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

The question is, now, what are we to make of this statement? Do Thomas & Johnston mean for us to believe that they do more than the single character per film? Does it mean that, like all underprivileged animators everywhere, they now receive scenes rather than characters? Are they trying to tell us that the old, publicized method of animation they did during the “Golden Days” no longer exists?

To be honest I don’t know. Also when are they talking about? At the start of the Xerox era? In the days since Woolie Reitherman has been directing? Do they mean ever since they’ve retired and started writing this book?

Let’s go back a bit.

- In 101 Dalmatians, Marc Davis did Cruella de Vil. That’s it. That’s all he was known for in that film. Oh wait, there were a couple of scenes where he did the “Bad’uns,” Cruella’s two sidekicks. He did these ging into or out of a sequence. In Sleeping Beauty (if we’re going back that far) Davis did Maleficent. Oh, he also did her raven sidekick.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

- Milt Kahl did Prince Philip in Sleeping Beauty – and every once in a while his father. He did key Roger and Perdita scenes in 101 Dalmatians. He did Shere Khan in The Jungle Book.

Kahl also seems to be the go-to-guy when they’re looking to have the character defined. The closest thing to Joe Grant’s model department in the late Thirties. If you weren’t sure how Penny might look in a particular scene, you might go to Kahl who’d draw a couple of pictures for you. But that was Ollie Johnston‘s character. You’d probably go to him first, but Johnston would go to Kahl if he needed help.

Kahl also did Robin and some of Maid Marian in Robin Hood. I could keep going on, but let’s take a different direction.

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

Look at one of Thomas’ greatest sequences, the squirrels in the tree. Starting with Seq.006 Sc.23 and almost completely through and ending with Seq.06 Sc.136 Frank Thomas did the animation. That’s a lot of footage. Yes, that represents four characters: Merlin and Wart as squirrels, as well as the older and younger female squirrels. He did the whole thing (and it’s one of the most beautifully animated sequences ever.)

But when he was done with that and needed work, he didn’t stop on this film; he also did a bunch of scenes in the “Wizard’s Duel” between Merlin and Mad Madame Mim. Another big chunk.

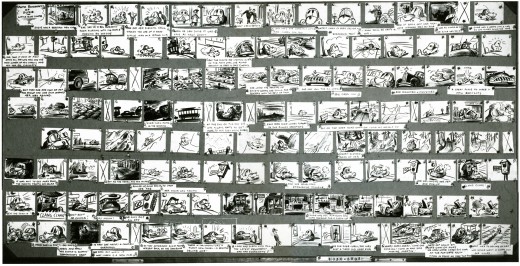

Hans Perk has done a brilliant service for all animation enthusiasts out there. On his blog, A Film LA, he’s posted many of the animator drafts of feature films. You can find out who animated what scenes from any of the features.

However as Hans posts the batches of sequences, he gives little notes about what we’ll find when we open the drafts. In my view, Hans’ notes are also a treasure.

You can read remarks such as, “Masterful character animation by Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas, action by John Sibley and a scene by Cliff Nordberg.” That seems to tell us everything.

In Sleeping Beauty we can read, “This sequence shows, like no other, the division between Acting and Action specialized animators. Or at least it shows how animators are cast that way. We find six of the “Nine Old Men”, and such long-time Disney staples as Youngquist, Lusk and Nordberg, each of them deserving an article like the great one on Sibley by Pete Docter.”

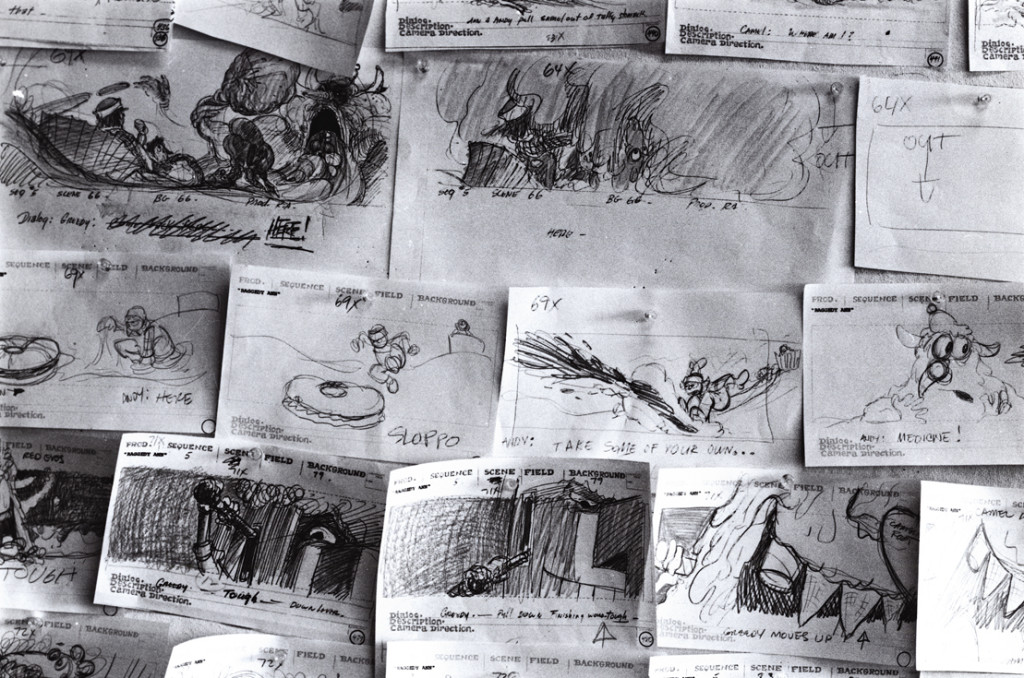

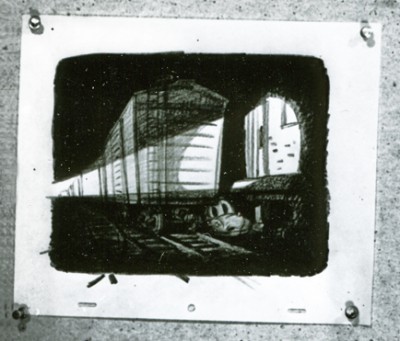

Or in The Rescuers we read, “Probably the most screened sequence of this movie, the sequence where Penny is down in the cave was sequence-directed by frank and Ollie. They would plan their part of this sequence in rough layout thumbnails, then continue by posing all scenes roughly as can be seen in this previous posting.

“They relished telling the story that Woolie told them the animatic/Leica-reel/work-reel was JUST the right length, and when they posed out the sequence and showed it to Woolie, he said: “See? Just as I said: just the right length!” They kept to themselves that the sequence had grown to twice the length!”

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

The work, right to the retiring of all of the “Nine Old Men,” would seem to me to prove that these guys, regardless of whether they added one or two other characters to the scenes, did, in fact, take charge of the one starring character.

This continues past the retirement of all the oldsters: Glen Keane animated the “beast” in Beauty and the Beast. He animated Tarzan in Tarzan, Aladdin in Aladdin, Ariel in The Little Mermaid, and Pocahontas in Pocahontas. Andreas Deja animated Jafar, the Grand Vizier in Aladdin, Scar in The Lion King, Lilo in Lilo and Stitch, and Gaston in Beauty and the Beast. Mark Henn animated Belle in Beauty and the Beast (from the Florida studio), Jasmine in Aladdin, young Smiba in The Lion King, and Mulan and her father in Mulan.

Need I go on? What are Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston talking about in their book? I’m confused.

I have a lot left to say about this book, much of it good, but next time I want to write about something else that confuses me with another somewhat contradictory statement in the book.

This has gotten a bit long, and I have to cut it here.

1

1

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 18

18 19

19 20

20 21

21