- Animated features, like some of the shorts, come and go. While working on it, there’s often an expectation that THIS will be the film to catch gold and change history. It doesn’t happen often.

Looking back on a puff piece from some past feature is oftentimes ludicrous; sometimes it’s just sad. Here’s a 1981 story from Millimeter Magazine about Hanna Barbera’s upcoming feature, Heidi’s Song. It sounds like it may be the future, but really it’s even hard to remember the film. It certainly didn’t change the world.

Hanna-Barbera:

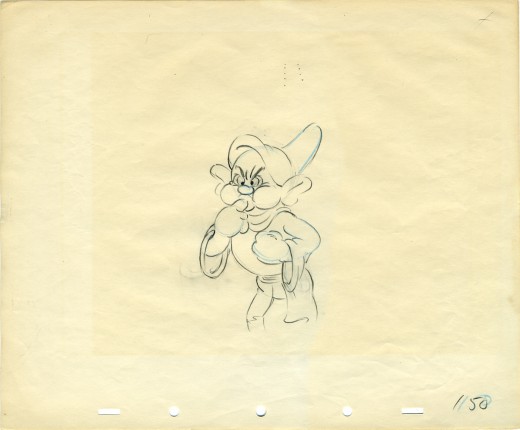

Will HEIDI’S SONG be its SNOW WHITE?

by John Canemaker

Hanna-Barbera Productions Inc. is such a giant corporate entertainment entity that it prompts the old joke: What does a two-ton canary sing? Any damn thing it wants! This Hollywood “canary” tias expanded since 1957 to become the wold’s largest producer of animated TV series andspecials; more recently Hanna-Barbera has become involved in themed amusement parks and live action movies for television.

Now H-B is eager to enter and conquer the sacred Disney domain of fully animated, “quality” feature-length animated films for theatrical release. William Hanna and Joseph R. Barbera hope to do so with an expensive flourish this summer when they will premiere HEIDI’S SONG, a $9 million cartoon feature that has been in production for five years. The film’s staff of 200-plus includes 12 background painters, 60 assistant animators, eight layout people, and 18 top character animators. All cut their teeth years ago at the Disney studio, or at MGM, working with Hanna and Barbera during their halcyon days in the 1940s and ’50s producing Tom and jerry shorts and animated segments for live action features such as Jerry the Mouse dancing with Gene Kelly in ANCHORS AWEIGH.

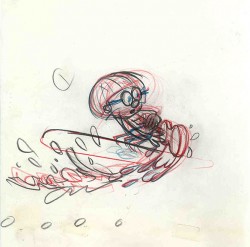

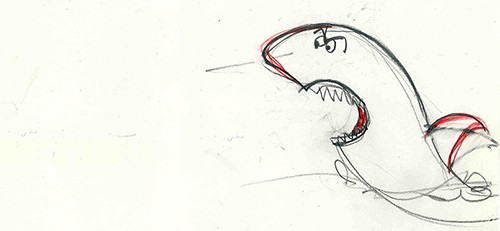

A moment of menace for Heidi whose voice is dubbed in by

Broadway actress Margery Gray in the Hanna-Barbera feature.

Joseph Barbera claims HEIDI’S SONG will be “a step forward in animation that’s very exciting.” But perhaps it will actually be a welcome artistic step back—a comeback of sorts—for Hanna and Barbera, who were once considered by their peers and the public to be superior cartoon craftsmen, winners of seven Academy Awards for two decades of beautifully timed and fully animated Tom and Jerry cartoons. In the 23 years since forming their own company—a factory geared to the production of “limited” animation series, a reduced form of animation that, as an H-B publicity release points out, “ignored the time-consuming and expensive detail that would not be visible on the dimly lit video screen”—Hanna and Barbera have produced over 20 TV specials and some 60 series (“Huckleberry Hound,” “Yogi Bear,” “The Flintstones,” “The Jetsons,” “Scooby & Scrappy Doo,” and so on).

In other terms, H-B produces more film footage in a week today than it did in a year at MGM. The principals’ choice to, as they say, “exploit a niche Disney had missed in family entertainment, with low cost cartoons for television,” has made the two men cartoon tycoons, rich beyond their dreams. They claim “there is not one hour out of every 24 that a Hanna-Barbera cartoon is not entertaining some segment of the world’s population.”

When, in 1967, Taft Broadcasting Company of Cincinnati acquired H-B, the company expanded its operations into five themed amusement parks, including Kings Island (Cincinnati) and Marineland (Los Angeles), where life-sized replicas of H-B characters—Yogi, Huckleberry et al — roam about greeting visitors. More than 1500 licensed manufacturers world-wide turn out 4500 different products bearing likenesses to H-B characters, for example, Flintstone window shades, Scooby-Doo pajamas.

In 1978, H-B won an Emmy, this time for a live action TV movie, “The Gathering,” starring Ed Asner and Maureen Stapleton; more live action films are planned for theatrical release and TV. With all this success, why would Hanna-Barbera bother pouring money into turf that is traditionally Disney’s and has proved to be a producer’s graveyard, from GULLIVER’S TRAVELS (1939) to RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY (1977)?

Company is built on cartoons

One should not forget that cartoons are the heart of the H-B corporate structure (as they are at the Disney studio). And it must be noted that as popular as the TV series are with small children, there is, to Hanna and Barbera’s distress, a persistently vocal, mostly adult contingent that just plain doesn’t like their cartoons! Veteran animator/director Chuck Jones, for instance, dismisses the whole breed of limited animation TV fare as “illustrated radio!” Writer Leonard Maltin once denounced H-B cartoons as “consciously bad: assembly-line shorts grudgingly executed by cartoon veterans who hate what they’re doing.”

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

Years of this kind of criticism (and worse from TV critics, parents groups and, most painfully, professional peers) has hit Hanna and Barbera right in their pride of craftsmanship. Witness Bill Hanna’s responses during an interview with Eugene Slafer: “Are you accomplishing what you believe is good TV animation?” asked Slafer. “No, I do not,” came

__Director Robert Taylor states that HEIDI’S SONG has _______Hanna’s candid reply.

__“a style unto itself, more like a live action picture in_______ To a further probe, “Have

__the staging, as opposed to what you’d see in animation.”____you ever been ashamed of your work, especially since parents have ranted about the general lack of quality on Saturday morning cartoon shows?” Hanna admitted, “Actually I feel like I should crawl under a seat sometimes.”

Joe Barbera recently spoke with Millimeter about his partner’s abilities to recognize the difference between good and bad quality animation and their alleged lack of craftsmanship. “We had to get that stuff out for Saturday morning,” he explains. “That’s a budget problem. Believe me, I don’t stand still for people saying, ‘Oh, they’re doing junk! They don’t know how to do…. ‘We’re not doing that. We only do it because you don’t get the money to do it differently. When we get the money —and you’re talking about millions—we doajob!”

So perhaps the initial thrust for the HEIDI feature came from Hanna’s and Barbera’s desire to prove they haven’t forgotten how to produce animation in the “classical” style, or how to create memorable characters that affect more than an audience’s funny-bone. Of course, Hanna and Barbera are too business-wise to produce a full-animation feature merely to assuage pain dealt their pride; there also had to be a bedrock of financial motivation behind the move and, sure enough, there was. “The thrust,” states Barbera, “was to do one every year and to build a superb perennial library, which Disney had for years.”

The Disney animated features, from SNOW WHITE (1937) to THE RESCUERS (1977), are re-released like clock-work every seven years, just in time to greet a new generation or to remind an older group of their existence. “They are,” says Barbera admiringly, “forever pictures;” that is, films that keep the Disney empire well-oiled with money derived from box office returns (pure profit, since there are no production costs on re-releases), and from lucrative merchandising spin-offs, like comic strips and dolls for themed amusement park rides. This money-making machine depends upon the public’s continuing affection for the cartoon characters and their “classic” stories found in the Disney features. Hanna and Barbera have not yet fully entered this profit arena, but they have been working on it.

Previous animated features

HEIDI’S SONG is not H-B’s first attempt to produce an animated feature. There was, for example, HEY THERE, IT’S YOGI BEAR in 1964 and A MAN CALLED FL1NTSTONE in 1966, both low-cost, limited animation, based on the one-dimensional characters from TV. Neither film was a “forever” picture.

There was,”in 1973, an H-B version of E.B. White’s book Charlotte’s Web, but this, too, suffered from the taint of limited animation and questionable production values. Reviewer Vincent Canby of The New York Times said of the film, “Parents will survive it, and so will the children.” Barbera acknowledges there was “a problem” with CHARLOTTE’S WEB, but to him it was a misjudgment of the financial potential of the material. “Charlotte’s Web,” says Barbera, “is an American classic. It is not an all-world classic. Germany ended up calling it Zuckerman’s Pig, after the name of the man who owned the pig in the story, because who ever heard of a Charlotte’s Web? The film version is recouping some of its money on Home Box-Office TV, on video cassettes and in non-theatrical markets, a fate H-B hopes to avoid for HEIDI’S SONG.

While Disney can produce almost any project known or unknown because of the sales value inherent in the name, “Disney,” Hanna-Barbera is not yet in that sublime position. To the general public, “Disney” means full-animation, perfect technological craftsmanship, beloved characters in stories containing mythic or nostalgic associations. To the same public, “Hanna-Barbera” means limited animation of flat characters on redundant television series. H-B seeks to improve its image with HEIDI’S SONG.

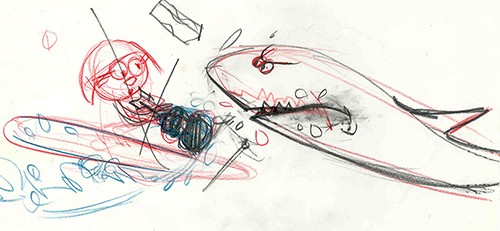

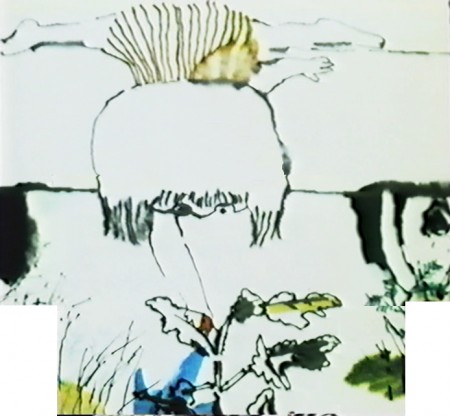

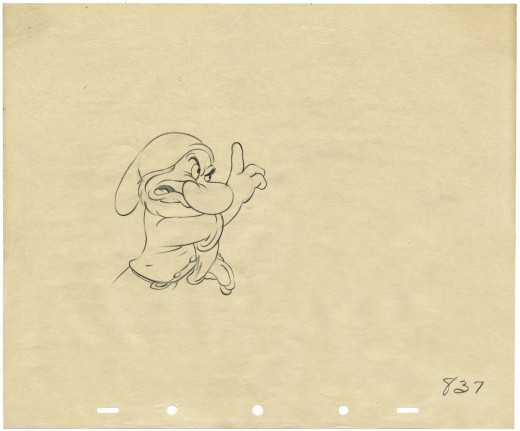

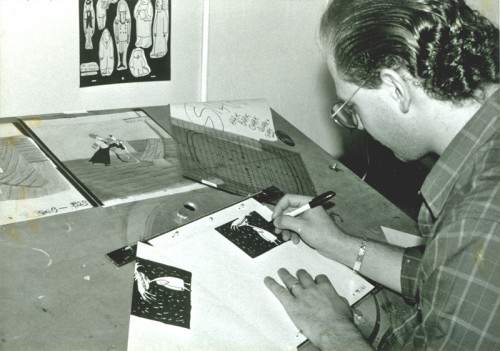

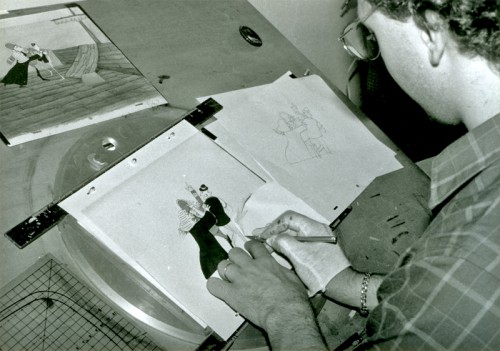

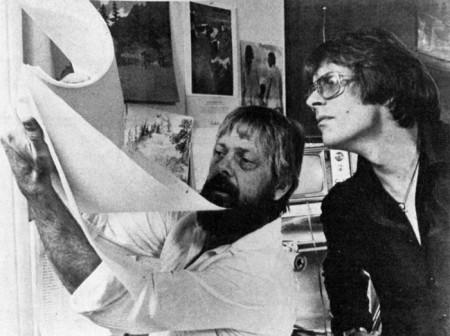

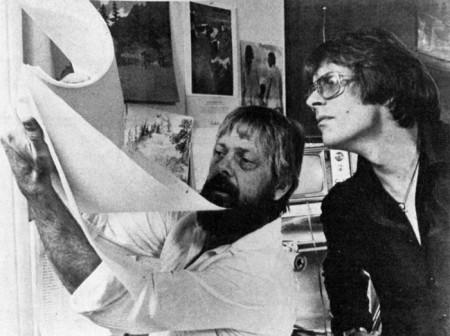

Animator Charlie Downs (left) flips drawings for director Bob Taylor.

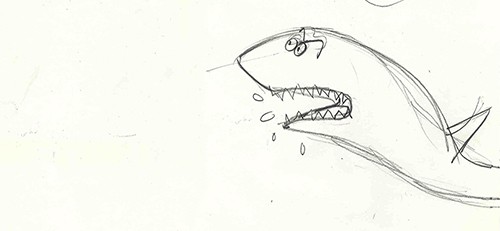

HEIDI’S SONG is the story of an orphan girl, based on Johanna Spyri’s 100-year-old, internationally known book. The cartoon feature contains a”Broadway” score of 16 songs by veterans Sammy Cahn (lyrics) and Burton Lane (music). The characters’ voices include Lome Greene as Heidi’s reclusive grandfather, Broadway actress Margery Gray as Heidi, and Sammy Davis, Jr. as King Rat, leader of a band of rodents. Other characters include a “mean and scary ancient housekeeper,” Fraulein Rottenmeier; Sebastian, “the butler who helps Rottenmeier be miserable to Heidi”; Clara, a lonely girl “confined to a wheelchair”; Peter, “a young goatherd, agile as the animals he tends.”

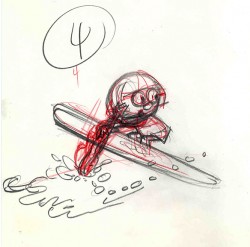

Off-setting the human characters is a gaggle of animals; Spritz, Heidi’s “feisty” pet goat; Hooter, a baby owl who “warns Grandfather of Heidi’s imprisonment in the cellar”; Gruffle, Grandfather’s “gruff old hound”; Schnoodle, a “nasty little dachshund who is rotten like his mistress, Fraulein Rottenmeier.” There is also a “crusty” German Schnauzer, a white mare, a white kitten and the aforementioned royal rat, “the power-loving and peppy leader of the rats in Sebastian’s basement, who spurs his clownish rodents into a strong force to attack Heidi.”

“We do have our animals,” points out Barbera. “My gosh, if we don’t have animals, we’re in big trouble,” he notes with an eye toward audience appeal and merchandising. “But we do have humans and some marvelous dancing,” he continues. “We are not rotoscoping,” he says, referring to the technique of animators tracing frame-by-frame projections of live-action. “I don’t care for rotoscoping at all.”

Choosing talent

Hanna and Barbera have instead hired a team of 20 top character animators—”Let’s use the word humbly and respectfully: the old-timers, “adds Barbera—people like Hal Ambro and Charlie Downs, both of whom specialize in human figure animation and have worked on films such as Disney’s PETER PAN and Richard Williams’ RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. There are also master animators of animal caricatures and comic timing, such as Irv Spence and Ed Barge, veterans of the fine Tom and ]erry shorts. Th’e great Disney/MGM animator, Preston Blair, was also involved with HEIDI for a time.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

One might assume that the difficult task of manipulating the drawn human form in full animation is what kept the film in production for five long years. Barbera, however, offers this explanation: “When we are in the slow season, which happens in television all the time, everybody has to be laid off. We were going to keep people busy on the feature. We found that doesn’t work. The kind of people you use on a feature are the old super-pros of our industry, and there are few of them left.

“Secondly, we wanted to use HEIDI’S SONG as a training ground for new animators. The first three or four years the picture would go into production and stop, then go back into production and then stop. That was not good for the picture. We were losing momentum, the enthusiasm of the artists and the excitement we wanted to build up. So finally, about a year and a half ago, we marshalled the last remnants of

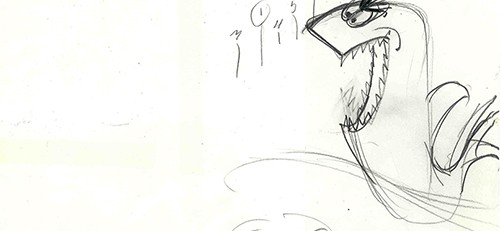

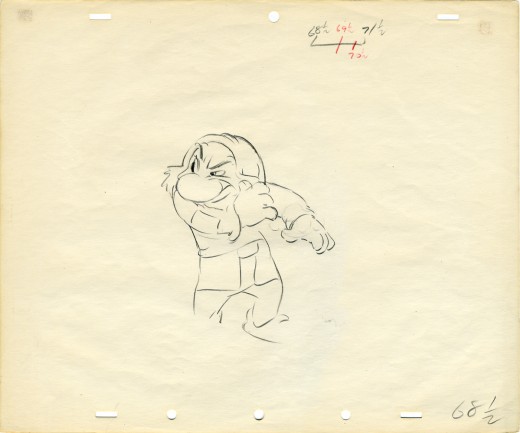

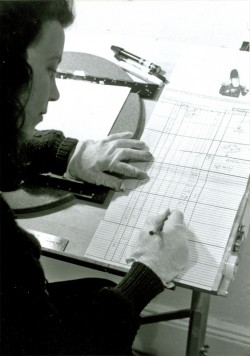

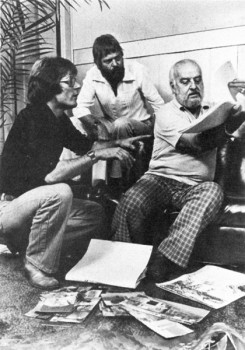

__Bob Taylor, director, and animators____ what we think are the best people in the

__Charlie Downs and Hal Ambro. ________business. When we brought these people in we had to change directors. We had a fine guy, but he had forgotten how to go back and really work these old-timers — really get the good animation! We then hired a brilliant young director, Bob Taylor, who is dynamite!”

Prior to rejoining H-B a couple of years ago (he had first worked there in 1966 for one year), Robert Taylor worked for Ralph Bakshi, Steve Krantz, DePatie-Freleng and Murakami-Wolf. “I always seem to come in on things that are hopeless,” he commented recently, “and we try to turn them into hopeful. I think we’ve done it with this picture. For me and the whole crew, and for Joe and Hanna-Barbera and Taft, this is our entrance into real good quality stuff!”

It has not been a piece of cake for Taylor. When he took on the HEIDI assignment, the script was written and the tracks were already recorded. “It was a hang-up for me,” he admits. “That’s the albatross around my neck. The story is episodic. If I had written it, I would have made it a little stronger in terms of her emotions and some of the dialogue. But,” he adds brightly,

I “my whole trip is to keep the audience entertained—get people to go to animated films and make them feel when they come out that they’ve seen something they can’t see anyplace else. It isn’t so much the tools;

i it’s what the hell I’m trying to do with it.”

Trying to elicit a description of the film’s style from both producer and director is difficult. According to Barbera, “The results have been what I call a Hanna-Barbera feature. It is not going to look like a Disney picture, or a FRITZ THE CAT or a RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY. We have our own style.” When pressed, Barbera cites “some very imaginative pieces of business.” Pressed further: “We’re not holding back. When they lock Heidi in the cellar, that’s a scary place—to be locked in a basement in a house in Frankfurt in the 1880s, that’s enough to put you away. We’re not holding back, yet we’re keeping it in good taste throughout.”

New wave animation

Taylor was a bit more specific: “I hate to opportunity for the guys to get back into what it’s really all about. We take as many new animators as we can bear—the ones that have the enthusiasm and are really interested in what we’re calling a ‘renaissance.’ But even more important, we are just interested in making great animated films and updating them into the 1980s.”

The HEIDI unit has already begun production of its next two animated features, ROCK ODYSSEY (which Barbera describes as “a marvelous treatment of music from the 1950s, ’60s and 70s. A rock-FANTASIA, if you want to call it that”), and NESSIE COME HOME, a tale about the Loch Ness monster. Again, the thinking behind the choice of both projects is carefully calculated toward maximizing box office. “If you are going to do a feature,”reasons Barbera, “you must have something people will identify with. You can’t do ‘Willie the Glowworm!’ That’s why HEIDI is so great. It’s always a problem finding material. Watership Down is a marvelous book, but we would have hesitated to do it because it’s just not that well known. It’s a gamble. You have to put four to five million dollars into something like that.”

Marketing concepts for animated features

At a time when Disney films are attempting to woo an older (“PG”) audience, one wonders why Hanna-Barbera appears to be aiming toward a traditional, family-oriented “G”-rated audience with its animated features. Barbera explains: “First of all, anything that Disney has done is going to play forever, so he will have that constant market in every media. Secondly, the theater audience isn’t going to be the only audience. There are going to be cassettes, a perennial that will run forever. And thirdly, we are going to have our own style. We’re not going to have a picture that will be only for kids. We will get the adults with this one.”

“ROCK ODYSSEY,” continues Barbera, “will appeal to those between the ages of 18 and 35, but we will not lose the kids because of the animation. And we will have the adults that remember those ’50s and ’60s songs. NESSIE will have a great, I hate to use the word, ‘environmental’ appeal, but we will be protecting a character that’s getting it. If there are monsters in that lake, they get bothered—by submarines, depth bombs, cameras—more than any character in the world. We have a very unusual twist that will make it appealing.”

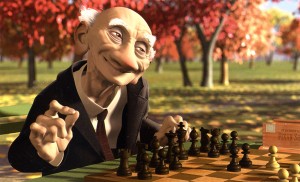

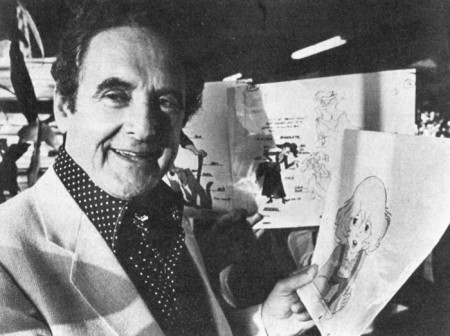

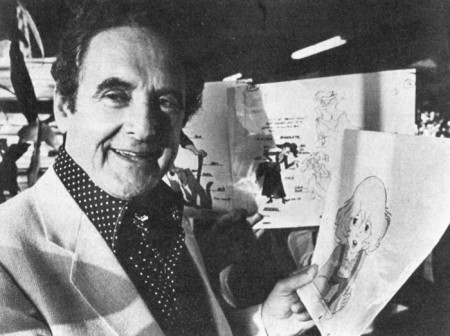

Joseph Barbara, executive producer, displays color models that some

150 animators used for reference while working on HEIDI’S SONG.

Asked whether the future might see Hanna-Barbera producing adult-oriented features a la Bakshi, Barbera answers, “Oh yes, very much! We had a recent all-day meeting where the thrust was the fact that we can’t depend on the children audiences to pay for these things. We must attract the adults, too. Statistics show there are less children around now. So whatever we do, we must attract the adults.” Barbera must have been thinking of a recent Bakshi product, i.e., LORD OF THE RINGS, for when asked if he would produce an unquestionably adult cartoon such as HEAVY TRAFFIC or FRITZ THE CAT, he replied, “No! I don’t think we would do that! We certainly wouldn’t shy away from a gutsy project, but it must bring in the kids, too. So there would be no bad taste.” For the time being, it is significant that Hanna-Barbera is training an enthusiastic crew in the techniques of full, character animation, one form of the art that for the last two decades has seemed to teeter constantly on the brink of extinction. It is enough for now that H-B is producing with integrity and care a film like HEIDI’S SONG, which will attract and appeal to large audiences.

The success of Hanna-Barbera will keep an avenue open for future animated features, and hold the public’s awareness of and interest in the medium of animation itself. With an increase in the number of future animated features will come diversity in form and content. Animation

as a vital and viable entertainment medium will then come closer to realizing its potential, as it did in 1968 when George Dunning directed YELLOW SUBMARINE, and in the early 1970s, when Ralph Bakshi excited audiences, and, indeed, as in 1937 when a struggling young producer named Walt Disney redefined the genre.