Articles on Animation 11 Aug 2009 07:24 am

Jules Engel on Teaching / 1976

- Here’s an article from the Feb. 1976 issue of Millimeter. It’s part of an article written by three separate Animation instructors: Yvonee Anderson (Yellow Ball Workshop), Greg Shelton (J.Marshall High School, Ind.), and Jules Engel (CalArts).

This is the piece written by Mr. Engel:

________________________________ by Jules Engel

When the Polish animator Jan Lenica toured America last year, he ended up in Los Angeles and came to visit California Institute of the Arts. After seeing a program of films made by the animation students at the Institute, he exclaimed in astonishment, “But these are not student films; they are films by artists! And here in Hollywood! Who would have thought?”

When the Polish animator Jan Lenica toured America last year, he ended up in Los Angeles and came to visit California Institute of the Arts. After seeing a program of films made by the animation students at the Institute, he exclaimed in astonishment, “But these are not student films; they are films by artists! And here in Hollywood! Who would have thought?”

Lenica is not the only one to have said this about Cal Arts and its animated “student” films, but the comments of so great an artist are particularly gratifying—and particularly revealing.

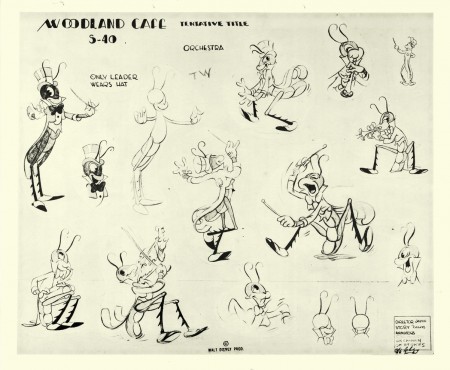

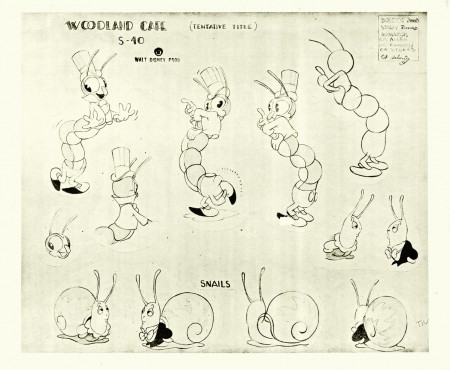

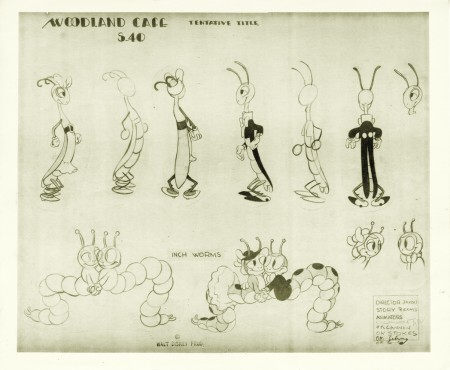

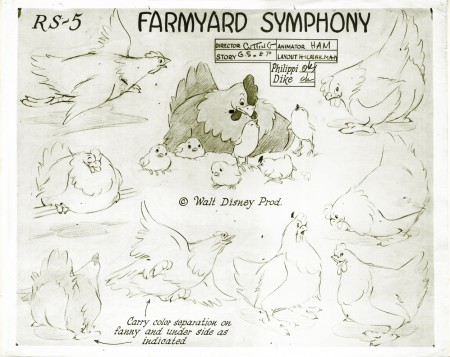

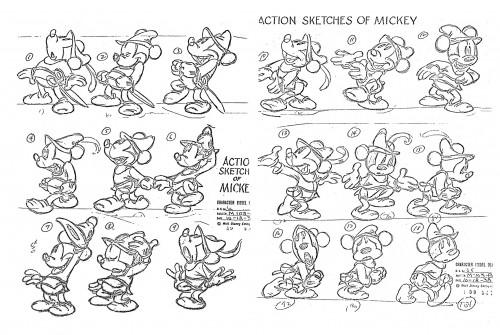

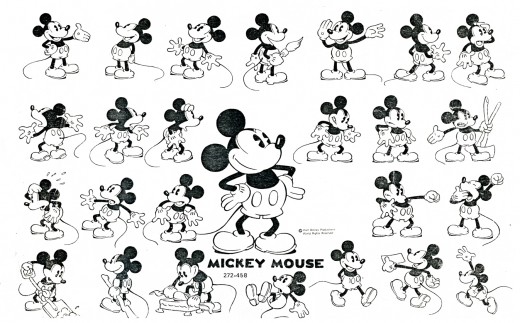

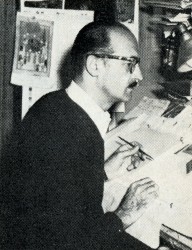

I began working with animation at the Disney Studios in the 40′s when FANTASIA was under production. I was one of about I200 people employed in the Disney

________ Jules Engel ___________ Studio—many of whose names are never recorded, though their contributions to the artistry of the films was considerable. I was hired as a choreography consultant for the Chinese and Russian dancers in the “Nutcracker Suite,” but

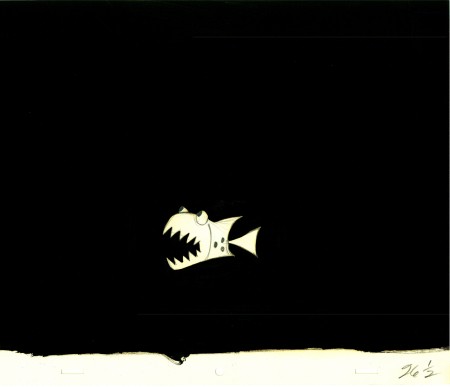

I drew out exacting choreography sketches for both sequences—up to 50 pictures for a one-minute movement—which were then passed on through countless hands (background artists, character animators, in-betweeners, eel painters, etc., etc.) before the finished film was able to be seen. Miraculously, many of my original conceptions—for example, the pure black backgrounds for the low-angle perspectives on the twirling Russian flowers—and the choreography on the Chinese and Russian dance actually survived into the final product!

I drew out exacting choreography sketches for both sequences—up to 50 pictures for a one-minute movement—which were then passed on through countless hands (background artists, character animators, in-betweeners, eel painters, etc., etc.) before the finished film was able to be seen. Miraculously, many of my original conceptions—for example, the pure black backgrounds for the low-angle perspectives on the twirling Russian flowers—and the choreography on the Chinese and Russian dance actually survived into the final product!

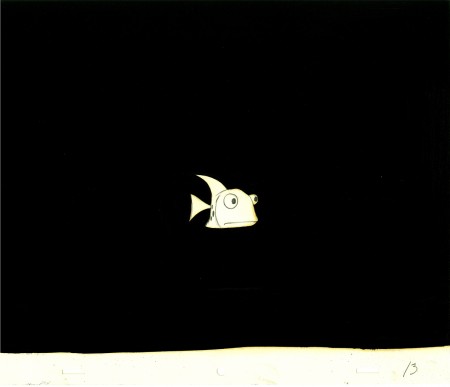

Later we founded UPA and opened up other possibilities of this much-maligned medium. With only about a handful of people, we were able to produce artistically integrated works. As a measure of our success, people quickly came to regard American animation in terms of two poles — ________ Engels “Accidents”

the Disney style, and the UPA style (always different,

with a range of subject matter and visual technique as broad as Modern Art itself). And “Disney” soon enough came under the influence of UPA by introducing more stylized elements into their previously realism-oriented product.

After UPA, I produced animation films independently with my own Format Films, including, in addition to Popeye cartoons and various commercials, a film based on a Ray Bradbury story, Icarus, which won an Academy Award nomination and a Gold Medal at the Atlanta Film Festival.

I had been offered jobs teaching painting and sculpture many times, but I had always refused, because I don’t really believe you can teach “art.” The ideas, feelings and meanings of artwork must come from inside the artist. You learn concepts and attitudes, techniques and materials of production. It is always better for the artist to learn about his art by trial and error. We learn through experience and experiencing.

But Cal Arts is different. When Anais Nin recommended me to Herb Blau, and then Robert Corrigan asked me to develop an animation program there, I accepted because I knew I wouldn’t be expected to teach “how” or “what” since the school is conceived as an artists’ conglomerate, as a co-operative workshop where painters and dancers, musicians and actors, philosophers and filmmakers could share their talents and experiences with each other. If one learns by a “how to do” method, one does not reveal one’s self, one only reveals the skill for doing.

Don’t take—search!

I don’t call myself a teacher, and I don’t consider the people I work with as students. They are “talents” or “artists” or “friends.” I hate to hear people say, “I taught him everything he knows.” That’s not education. In the first place, if “everything he knows” can be measured and categorized so easily, “it” must not be too much or too complex, and in the second place, education should be a process of opening and broadening horizons, so if “everything” has supposedly already been “taught,” the process must have been one of closing off possibilities rather than opening them up. Furthermore, a “student” must always have the feeling that he is working for and by himself, developing his own potentials, his own initiatives, his own ideas—not being obliged to or dependent on a “teacher.”

At Cal Arts I have something of an ideal situation. The working environment is not classroom oriented—but more like a working artist’s studio. It is an environment in which experiencing can take place. Studio is open 24 hours and seven days a week. An artist has no limits of working hours! Almost all of the exchange between me and my “talents” is on a one-to-one basis, since out of the 30-or-so talents I work with each year, there are maybe 20 different directions they want to go in.

I never discourage people, and I never force them. Work with the talent where he is, and not where you think he should be. I like to take chances on people and let them find out how they feel about animation. I encourage them to play around with the medium, and some fall in love with it while others learn that it’s not really a vehicle they find satisfying or profitable for their ideas or capabilities. In addition to my 30 full-time talents, I usually have I0 or I5 other talents who come in from other schools (dance, music, design, art) to try out animation. I never say no to anyone, because, after all, with young talent who can say which one is going to develop into something great? I end up working with a Jot of talents. I’m looking for the innovators, (as well as for the craftsman), the dreamers, the leaders. The great artists of animation—the Lenicas, the Fischingers, the Kuris, McLarrens, Hublys, Disney, undoubtedly weren’t model students (and maybe weren’t even pleasant people) because their genius was too eccentric. They broke all the rules, and invented new ones, and that’s precisely why we admire them.

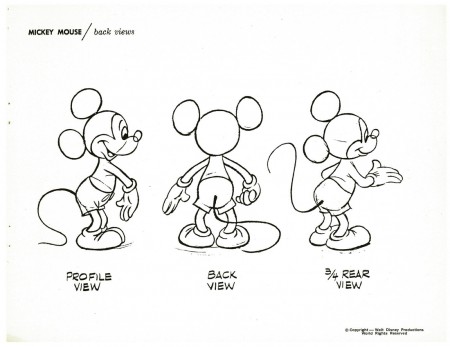

The talents I have come to me from widely varying backgrounds, too. Dennis Pies, for example, had four years of art school behind him and wanted to explore film as a means of adding a controlled time dimension to his paintings, which he did beautifully in films like Aura Corona. Kathy Rose, with a background of a dancer, came on as one of the most intuitive creative artists, winner of the Gold Hugo—at Chicago International (Mirror People). Jane Kirkwood had no experience at all with drawing, yet she produced a superb, award-winning film, drawing for An Exhibition, proof once again that animation is far from synonymous with drawing. Disney himself couldn’t draw all that well. So what!? He was an entertainer. He had the instinct of an actor—and an inspired director. He needed the craftsmen to complete his dreams.

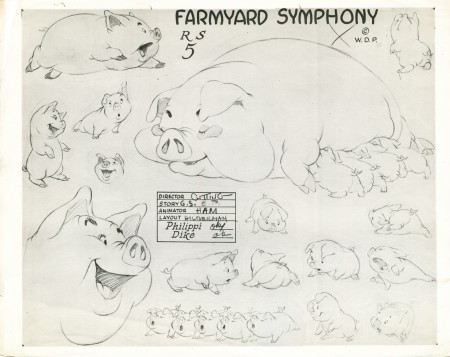

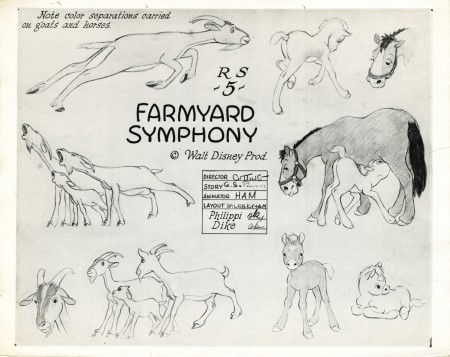

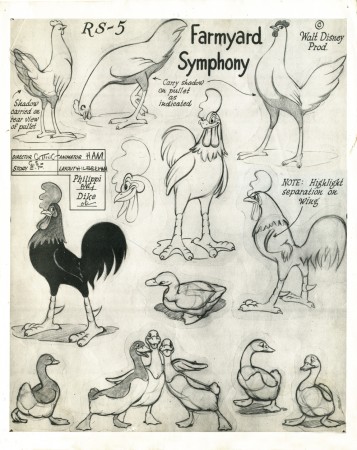

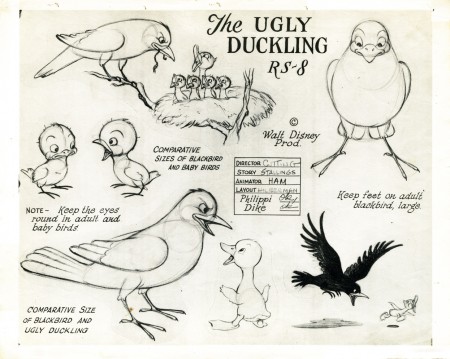

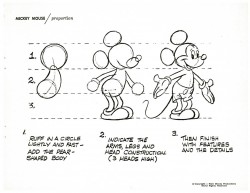

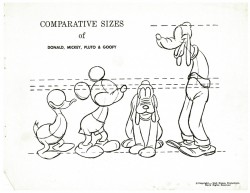

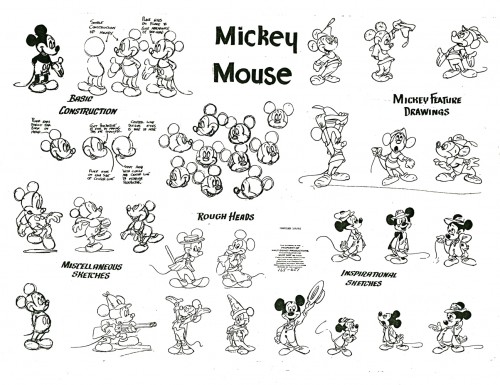

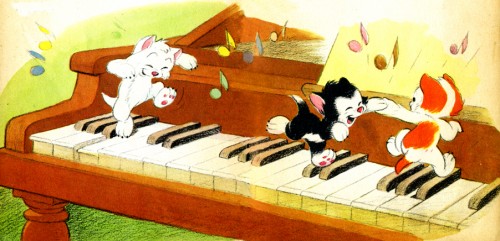

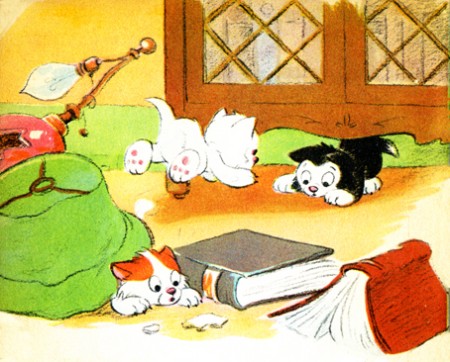

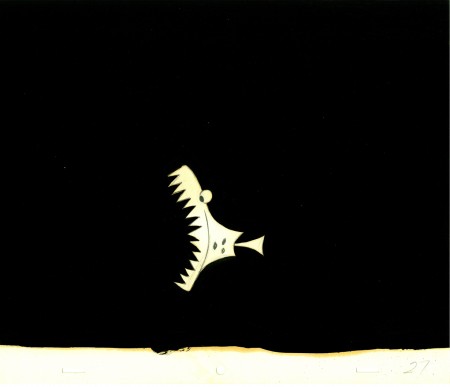

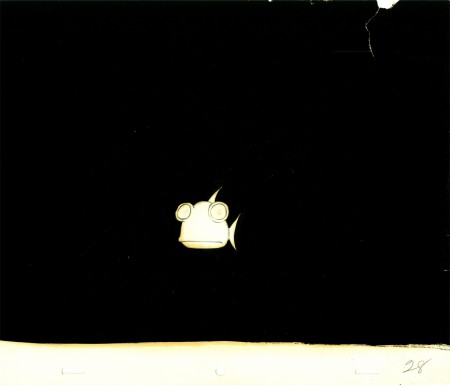

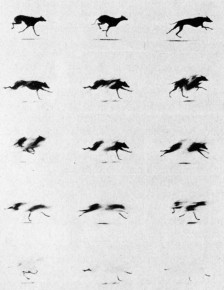

Films produced by students at California Institute of the Arts

Each talent has his own rhythm as well. It takes some people months to get acclimatized to the kind of freedom that I offer in order to find themselves on all levels: intellectual, spiritual, and intuitive. The artist has to discover for himself his own road. Then some talents work very slowly or irregularly, while others like the prodigious Adam Beckett have spent hundreds of hours laboring every day on the drawing board, the Oxberry and the optical printer for each of his five films. The most important part of teaching is not in reading and lecturing or even looking at films, but the actual “doing” of the film.

There is no competition in our classes, either. Competition creates a false sense of artificial tension which might be all right in sports where competitive performance is the only way to demonstrate your skill, but not in art where individuality and individual expression is supremely important. I don’t bother pointing up the talents’ bad points, since they stumble over those soon enough by themselves; I prefer to point up the good points and build on them—to give the talent a confidence in-themselves.

We have excellent equipment and I put together a fine collection of animation films which I show to the talents, and later they can study them for themselves, frame by frame, if they want, on the viewer in the library. We also have guest animators—Americans Mary Ellen Bute and Elfriede Fishcinger, Dragich and Matko from Yugoslavia, Richard Williams and Bob Godfriend from England, Yoji Kuri from Japan, and Dale (Further Adventures of Uncle Sam) Case, Leo Salkin, Herb Klynn, from right here in Hollywood.

Is our program successful? I think our films attest to that. And our talents have had no trouble finding jobs. Joyce Borenstein, for example, is already working for the National Film Board of Canada. If she had tried to learn animation through the studios, she would have spent five years as an in-betweener and five more years as an assistant animator before getting that precious director’s status-symbol, the stopwatch, which they can get the first day in my class and learn to use it at their own pace and in their own way. One day a beginning talent came to me and said, “Oh, I’m sorry about this; look at the mistakes I’ve made!” “No,” I told him, “you can’t make mistakes at this early stage. Mistakes you make later when you know better.” But strange to say, they don’t seem to get around to making too many mistakes later either.