- Amid Amidi in Animation Blast #8 printed a brilliant interview with Ed Benedict. There was another interview in the European magazine Animafilm 6, 1980. It was written by Dana B. Larrabee.

Ed Benedict on Animation

We have often dealt in our journal with the prospects of computer animation. We believe that also the views of an advocate of the traditional methods of animated film deserve popularization.

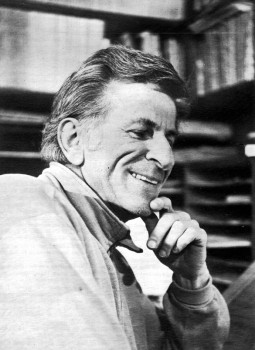

Ed Benedict first spoke to me on the telephone about an animated tv spot I had done for a local car dealer. When 1 learned of his extensive hack-ground in animation, I asked it” we might meet and talk further. Shortly thereafter we met twice at his home in Carmel, California.

Ed Benedict first spoke to me on the telephone about an animated tv spot I had done for a local car dealer. When 1 learned of his extensive hack-ground in animation, I asked it” we might meet and talk further. Shortly thereafter we met twice at his home in Carmel, California.

We talked mostly of the views Ed has developed during his forty-plus years in the animation business. From those interviews I have assembled the following for those interested in a personal ac-count of the craft and business of animated filmmaking as it has evolved in the United States.

It wasn’t a business. It was a group of guys that had to organize themselves for eight hours of the day basically.

In 1930 Ed went to work for the Walt Disney Studios as an apprentice inbetweener. The Mouse was an established cartoon character then, and Walt trying to launch a new kind of cartoon series that did not feature a regular character. These were the “Silly Symphonies”.

Ed recalled: – When I first worked at Disney’s (show you how thorough that guy was), we were required to make our own little animation tests. This is when we were just assistants. We’re not animators yet. I did a horrifying job when I think of it now, of a guy taking a horn and blowing it. That sounds pretty damn simple . . . and it could look like it too. And you could do it and it would look like, “Oh, brother! Is that keen!” A guy big, full of air: then blowing out, turns thin, you know. No animation. Just going from A to B. But we had to do it our own way. Start with nothing. No instructions. Just a blank piece of paper, and how many drawings we took to do it, that was our own thing.

We had to take all of our test papers in to the test-camera which was a little Tinker Toy baling wire rigged-up thing. This was at the first studio on Hyperion. He wasn’t making cameramen out of us. He was just rubbing our noses in the business.

So you got kind of an overview – I interjected.

So you got kind of an overview – I interjected.

Yes. An appreciation for every department. Then the cameraman would take it out and develop it – and not print it. We’d just look at the negative on the Moviola. We would get our strip of film and that was it. At the end of the day Walt would come around and look at it with us and just go over it.

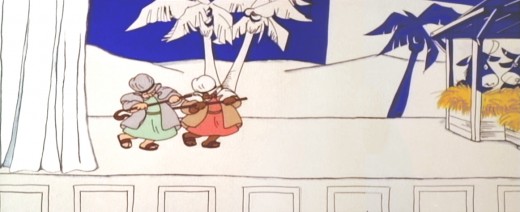

There was one of the early “Silly Symphonies ” called “The China Plate” (1931) when I was assistant to Rudy Zamora. One of the scenes was trucking in on one of these plates with Chinese scenes painted on it. Rudy had this scene and he was quite delighted to have thought to do this himself; I remember him leaning over to me, flipping the animated drawings saying: “Hey, how do you like this?”

You know these little Chinese girls with the little Chinese bobs? Straight bobs. Whether they ever had them or not, I don’t know. That’s the way we thought of them at the time. This little girl was to turn from left to right – but when she turned, the hair trailed across her face. That had never been done before. That’s a first beginning to loosen up things. Not only animating the figure from here to herc~but there’s little things on them too, where a thing will trail an action and then come back again and then settle down. It was just sort of lifelike.

He also worked under Wilfred Jackson {who had previously been an assistant to Ub Iwerks) doing breakdown, clean-up and inbetweening.

I’d been there a couple of months and we were working on this picture that had an Indian character ot a fox fighting with another character. I noticed that in this particular scene the fox’ tail was missing. When I remarked on it to Jackson, he said there was so much action that no one would miss it. I guess you could say that was my first experience with the “facts of life”.

He chuckled and continued: – Jackson was to later become a first class triple-plus director . . . and he was the last guy in the place that looked like it. A wonderful guy . . . straight . . . and he didn’t appear to have a sense of humor. He just didn’t look like he belonged in that business. But I guess he was the first genius of the directing end who knew to get the “Disney” out of the Disney Product.

In 1933 Benedict went to work for Walter Lantz at Universal as an assistant animator. Then he worked for Charles Mintz at Columbia for a year-and-one-half before returning to Universal where he became a full fledged animator. It look an average of four years to make animator, Ed recalls.

Then on the side with a co-worker at Lantz’, he set up an independent company. They first tried to interest Richfield Oil in the idea of animated billboards – a project Ed describes as “successfully unsuccessful”. Then he hit on the notion of selling commercial ideas to independent theatres. But without a distribution set-up, the idea “took a long time to develop into a state of nothing”.

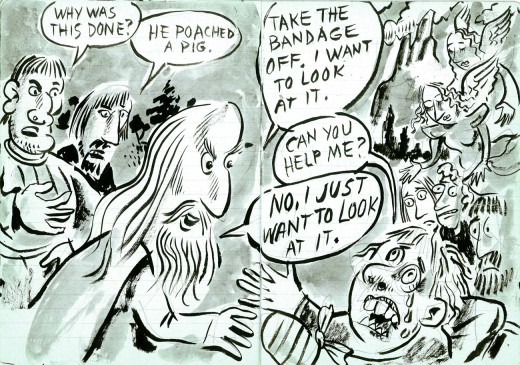

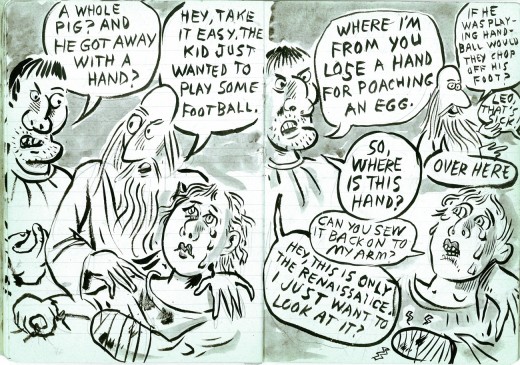

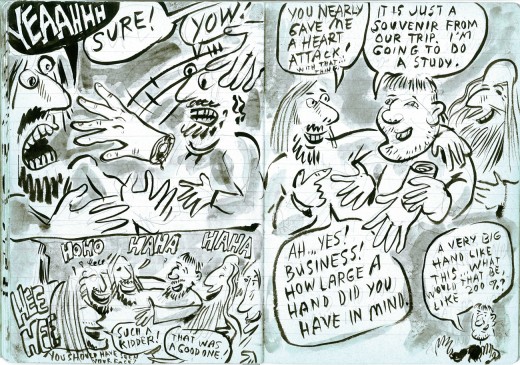

.

.

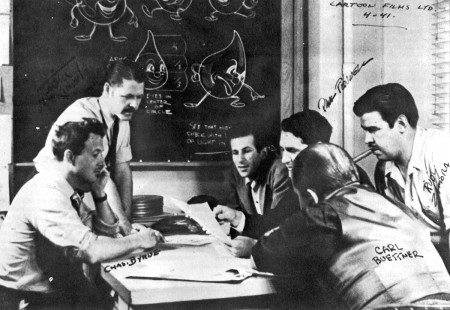

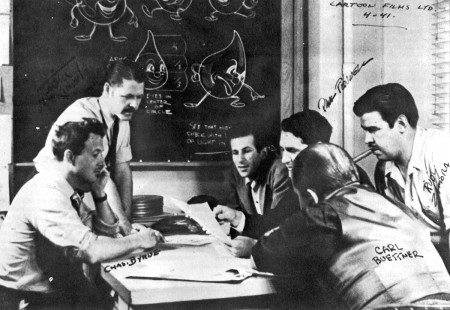

From 1938 Ed worked with Paul J. Fennel at Cartoon Films, Limited making commercials for Borden’s, Shell Oil, Rinso, etc. He returned to the Disney organization in 1942.

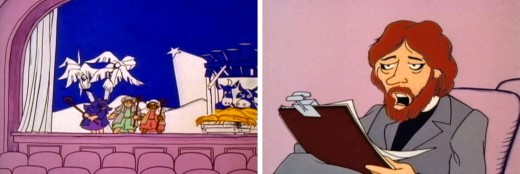

Did you work on “Willie, the Operatic Whale”? I asked.

Yeah. I worked with Ken O’Connor on that. An excellent artist.

Ed went on to explain about the drawing materials used by the animators.

The paper that everybody used to use was called Management Bond.

What kind of ink did they use on the cells? I asked.

I can tell you back then it was India. And there were Gillot pens and there were other kinds of pens for certain widths. And then they started getting these spread lines and working with brush. The girls had to be pretty sharp with a brush. You couldn’t just take any girl, like with a pen. A girl had to be trained with a pen for tracing before she’d get into brush. Ed was kept busy at Disney’s doing “war stuff”. He worked on an aerology series for the Navy and Victory Through Air Power as well as educational films. This period of employment with the Disney organization lasted three years. After the war, he took a leave of absence to help Paul Fennel found his own cartoon studio.

About this time United Productions of America, better known as U.P.A. was getting under way.

Now U.P.A. was my idol. U.P.A. was the greatest – Ed enthused. Steve Bosustow was living down in Santa Monica on the beach and one time I visited with him. And in one of the rooms on the wall was a bunch of story sketches that he wanted to show me, things they were working on. They were a little weird-ish compared with the typical bulb-headed looking things. They were attractive and intruiguing. And that was the beginning of U.P.A.

It was later taken over by a different outfit – made a garbage can out of it. Like the Dusenberg. gone. Period. End. Fin.

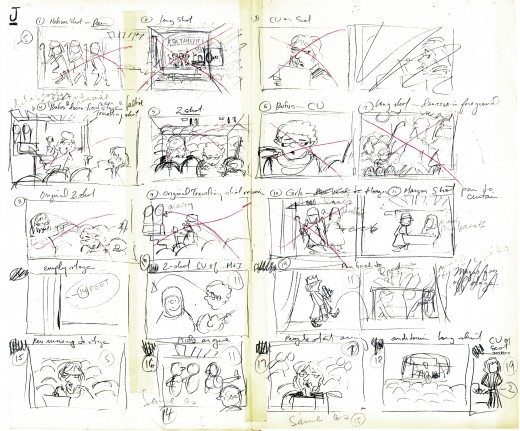

Later Ed called Tex Avery at M.G.M. (whom he knew from his days at Universal) and asked him if he needed a layout man. In animation “layout” refers to the design and relation of the cartoon characters to the backgrounds and to the total visual concept of the film as a whole.

Ed explained: – You see when I left Universal I was an animator. But with Paul I was laying out and doing the models – everything. So I got away from animation – animation bored me. I don’t know. I wasn’t a good animator. But my inclination ran towards more drawing. So laying out and models got to be my thing from then on.

By models, do you mean model sheets? For the characters?

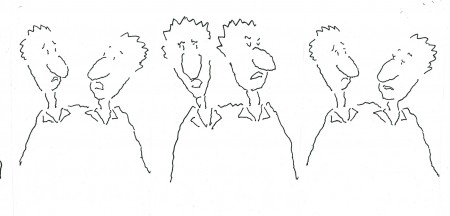

Not model sheets – models. Just a drawing of the one character . . . and overall three-quarter thing showing what it’s all about. Model sheets are based on models.

The model sheets are referred to by the animators as they work on their scenes. They show the characters in multiple views, different poses, expressions, etc., and their proportion to other characters they may be working with. By doing models Ed was designing cartoon characters.

At M.G.M. Tex Avery gave me a model sheet of Droopy to see what I would do to modernize it. He liked what I did and said; – Okay, come to work.

Later M.G.M. started cutting down. And TV started to cut in. So Tex’ unit was cut out. But Bill and Joe (Hanna-Barbera) wanted me to stay there and work for them. I didn’t work on “Tom and Jerry” – but other special pictures they were doing. Then the thing got cut way down. I left the place and was home doing comic books for awhile. And then I got a eall from Quimby (Fred Quimby was in charge of the cartoon units at M.G.M) to come in and talk to him about doing the set-up for this Gene Kelly thing. This was a whole picture -not just a sequence. It could have been really good-looking but they were all too sissy about it.

.

.

In the meantime Tex established his own commercial unit, Tex Avery Cartoons, and is sending over model jobs for me to do via one of the animators that worked at M.G.M. who was doing outside work for Tex. Hell, I was making more working a half-hour on a model (for Tex) on M.G.M.’s time than I made a whole day sitting there for M.G.M.!

Things were getting pretty hot over here, beginning to fold up. And Joe and Bill are working on things of their own. I did the Ruff ‘n’ Reddy models for’em. Anyway, we’re doing commercials over at M.G.M. for a while. For Schlitz, S-H stamps, and then the thing folded. Meanwhile I’ve been doing models and commercial layout for Tex. Hell, I’m making a minimum of twice what I was getting at M.G.M. I was doing all the H-B models “Huckleberry Hound”, “Quick Draw Me Graw”, “Flintstones”, etc. as well as the layouts. Now when they get loaded down at H-B, I get a call.

I asked Ed about working with the numbering system I’d heard was used at Hanna-Barbera. He called it a “file and number system”.

It was driving me crazy – he sighed. You would spend more time getting up from the board here and going over checking the files and numbers to see where you’re going . . . or looking up the right background. It would’ve been less work if I’d done the whole thing myself.

What about the u-nions? I asked. What’s the difference between the two, if any?

I can’t say what he is now – he emphasized. I can say of the middle era (The ‘forties and ‘fifties). The screen Cartoonists ‘Guild was considered a “Liberal” u-nion. The Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists was part of the I.A.T.S.E. It was considered the more moderate of the two.

If you’re looking for work in Hollywood, do you have to belong to the u-nion to get in down there?

Yeah. Furthermore, they’re not that long on work. So all the u-nion guys would have to come first.

I moved up here in ‘sixty-one. If the work followed me -fine. If it didn’t, the Hell with it! I’d had it. And I’d never liked it since I’d been in the business anyway. There were very few “talented” guys in the business. But the ones that had it – like Art Babbitt, Tom Oreb, John Hubley, Bob Cannon and Norm Ferguson – they were real geniuses! But many of the guys couldn’t draw their own breath. In the earlier days, the business was made up of cartoonists more than artists. Had there been more artists, there might have been a different picture.

Where did you think the future of animation lies?

I think it’s walking towards its grave. I can’t tell you how far it is between here and the grave. It’s like centuries ago when guys were carving with chisels, these ultra-fine hunks of lettering and sculpting in marble. The exactness. The fantastic things they were doing then. A guy could stand off and say: “Gee, that’s what I’m going to be when I grow up.” And you can go and keep saying it ’cause it was so beautiful, it was so superb-what’s better? But is it? There ain’t none of it. None. It’s just an old dead art.

Is that analogy valid for animation?

Sure it is.’

Why? Look at some of these television commercials…

That’s not animation. That’s using the animation medium … To me, most of it has no advertising value whatsoever… It’s just a lot of talk that somebody is trying to sell somebody and they’re not. The ad agencies are all wrapped up in their own immediately constructed little world. And they turn to each other and all of ‘em think: “This is ours”. Completely losing the total picture of whether it’s ours or yours or the next-door-neighbors’ . . . What’s it doing? What’s it supposed to do?

You don’t see any future in the business?

No.

Do you think it’s stupid to try getting into it?

Well, I can afford to be wrong. But for the most part . . . I would say “yes”. Stupid from the standpoint if you think you ‘re ever going to make something out of those things. But not stupid from the standpoint if you’re fascinated with it. If you’re intrigued to the point that nothing else will do, no, you’re not stupid. You’re smart. Go through and milk it . . . Being in the business was beautiful. Being in the business was keener than Hell. Informal! Friends of mine that had to work in offices – oh, they envied the Hell out of me. And I didn’t blame them!

With regard to the dollars and cents end of animated film making, Ed felt that the producer “might make a couple of bucks.” He cited ever rising labor and material costs as the main reason the profit potential in animation is lessened all the time.

Together we examined some “how to” books on animation by Eli Levitan and Roger Manvell. Later, Ed had this to say about them:

- Much of this stuff in the books was too much analysis. That never was done at all. That attitude just wasn ‘t there. It was more a natural reaction to things that they were seeing, or doing, or thinking.Finally we discussed “contemporary animation”. Ed took a pretty dim view of it all.

I was looking at these things on channel nine. And every one of ‘em are done in Yugoslavia or Arabia or some other place where the guys don’t make ten cents an hour. A gay is sitting down at a drawing board and doing anything that comes through his mind…I don’t even put it in the category of drawing. Animation? No such thing.

Have you seen any computer animation? I asked.

I have no use for it – he answered quickly. I have nothing but utter, unadulterated contempt for it.

Are you sure you’re not a little afraid of it?

Not in the least. It will never in your time touch animation. They are still a mathematically run machine. It hasn’t an iota of looseness. They’re finding out that computers have their limitations . . . It always has the same flavor, same attitude. It’s always there as a graph.

One can take issue with some of Ed’s opinions about animation as apart form and as a business. But what makes his remarks so compelling is his first-hand knowledge of the craft itself and of the many personalities who made the business of animation a “business”. His sentiments concerning the current “state of the art” are disconcerting to the animation enthusiast. But they are the outcome of his having been caught up in the rise and fall of the theatrical cartoon studio operations as well as the growth of a never, and to him, less satisfying sort of production geared to television.

I also suspect that this attitude stems from his own genuine concern for the craft – his frustration ai what animation has come down to as opposed to this notions of what it should be.

To some, Ed’s opinions may seem overly pessimistic. But before Ed would consent to this interview in preparation for this article, he forewarned me that he would not “romanticize the cartoon business”. He explained that this was his pet peeve with most of the articles and books that dealt with the history of his craft. And Ed Benedict was not about to further that sort of misrepresentation.

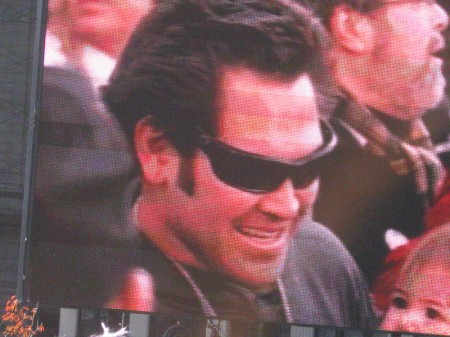

photos:

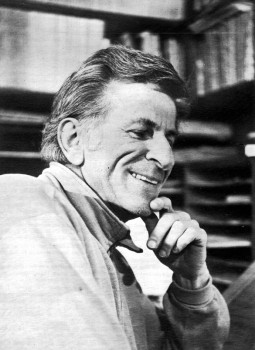

1. Ed Benedict

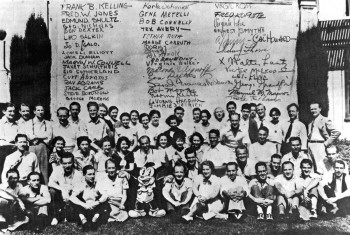

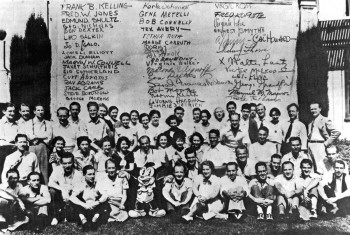

2. The Oswald the Rabbit team at Lantz

3. Ed Benedict among his collaborators

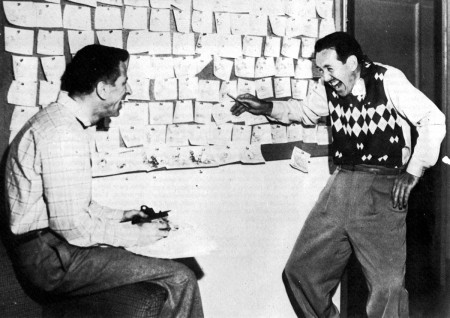

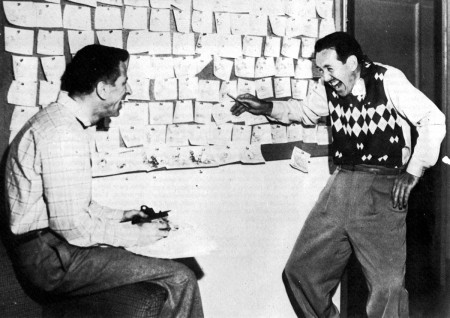

4. Ed Benedict and Mike Lah

_________________

A couple of comments.

- Sorry, I had to write the word “u-nion” that way because WordPress (on several different computers wouldn’t allow me to save that word. (Secret conspiracy?)

It’s unfortunate that Ed wasn’t asked more about his brilliant work at Hanna-Barbera. That’s where he truly came into his own and had such an enormous effect on the world of animation.

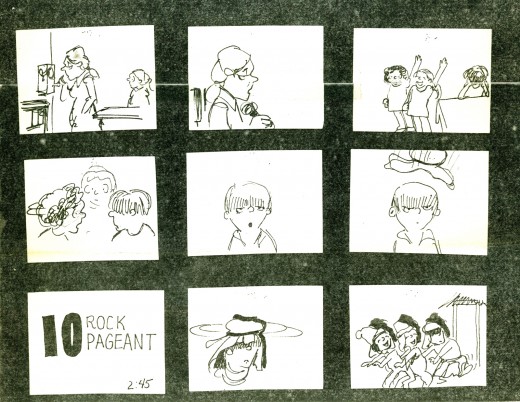

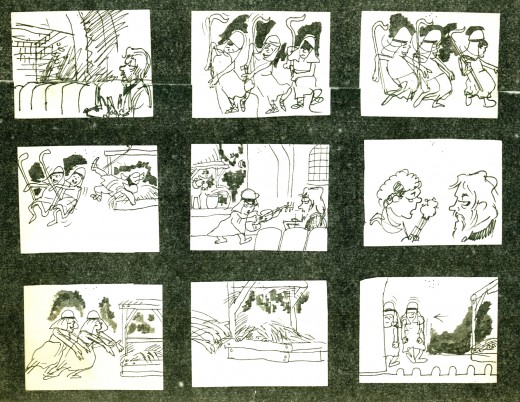

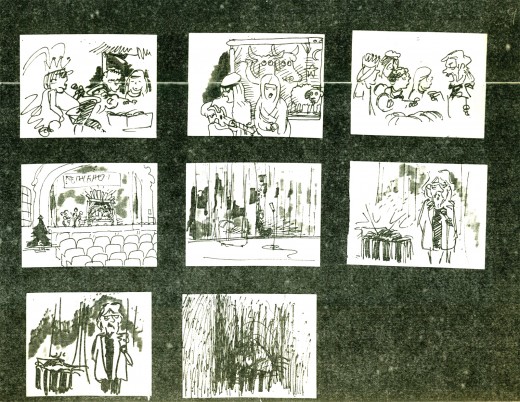

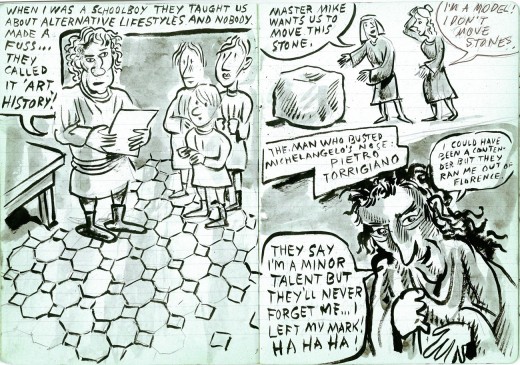

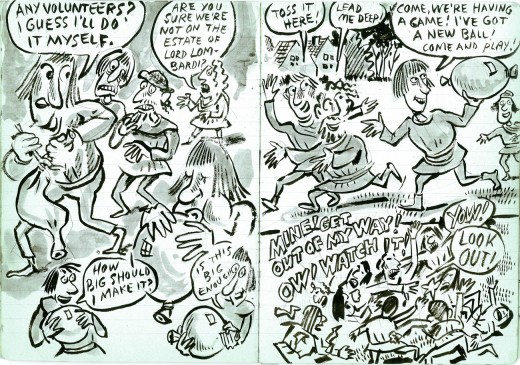

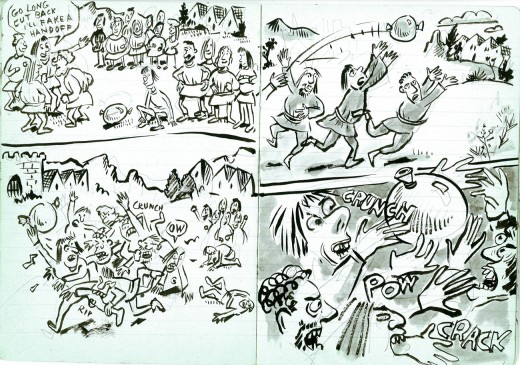

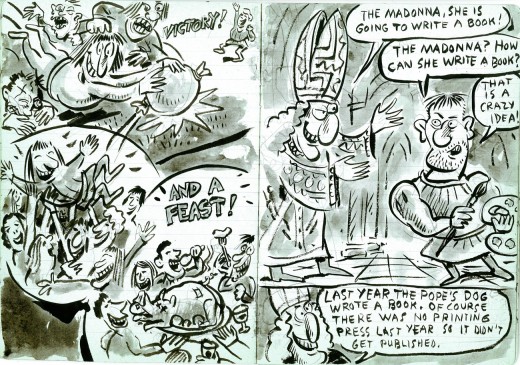

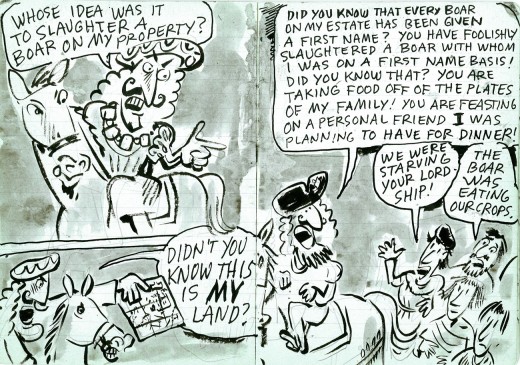

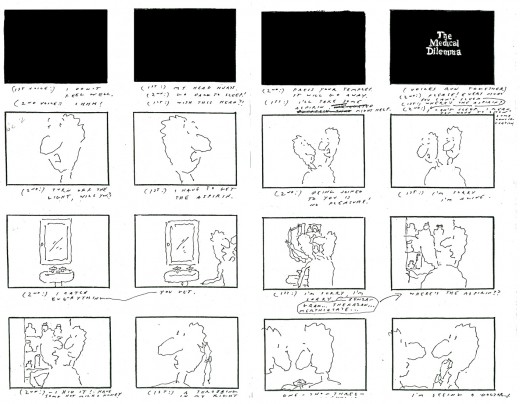

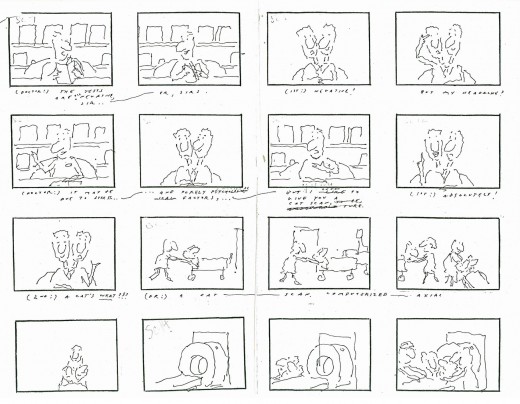

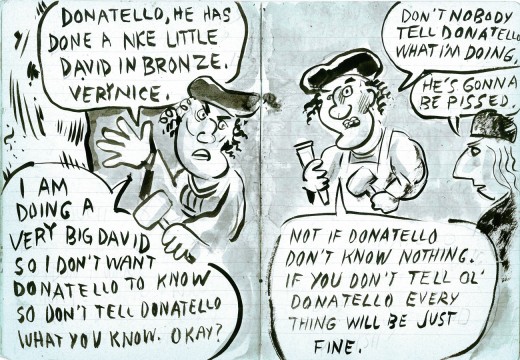

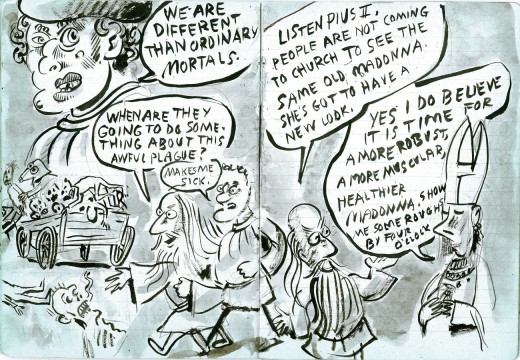

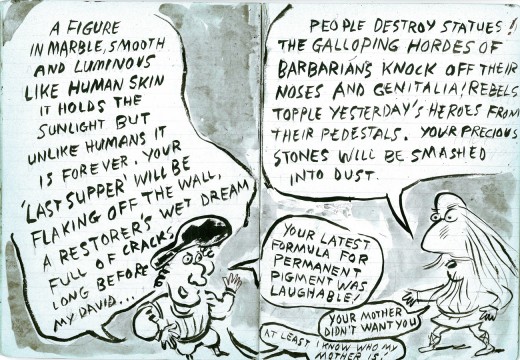

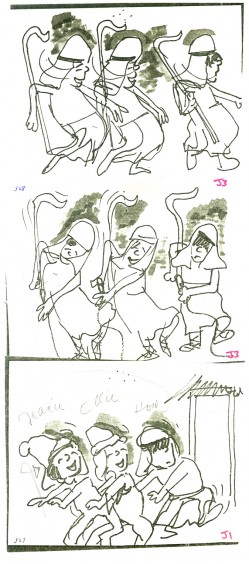

Cov

Cov J1

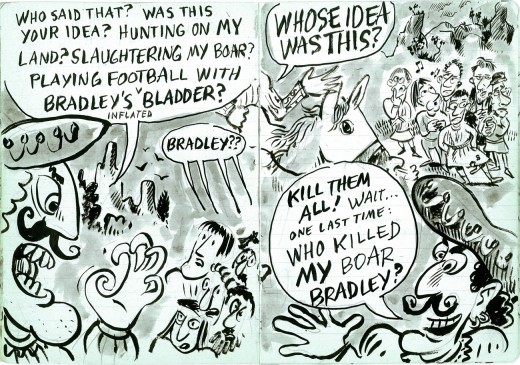

J1 J2

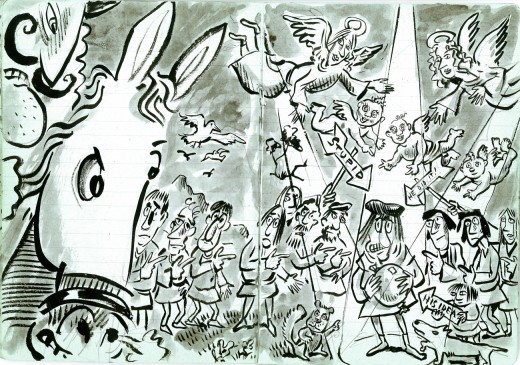

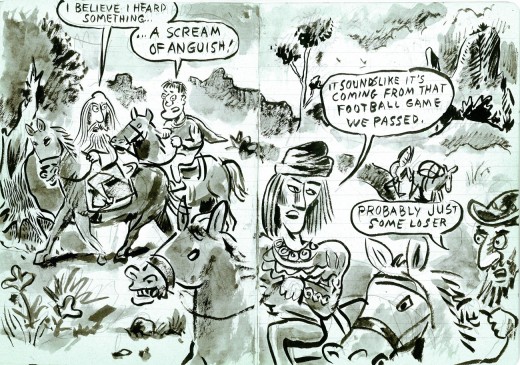

J2  J3

J3

J1

J1