- Len Lye, one of the original experimental animators, has rarely gotten the acclaim from the animation community that he has certainly deserved. Rarely is his name mentioned in animation books or articles. As a matter of fact, in more than 50 years of reading about animation, I can only remember two significant magazine articles about the man and his work that appeared in animation magazines. (If you really go looking you’ll find a lot written in art publications – not animation mags.)

Here, I’m posting one fof those two that I think is a significant and clear article, and I hope it will give the man another five minutes of your attention. The article was written by Joseph Kennedy for the February 1977 issue of Millimeter Magazine.

Len Lye – Composer of Motion

by Joseph Kennedy

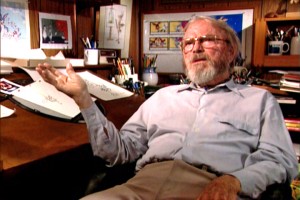

Len Lye‘s Greenwich Village loft is an airy workshop, filled with the tools of the artist’s trade: machine saws, diagrams, models of projected works, and several silvery kinetic pieces glistening in the summer afternoon’s light. Len Lye himself is the Renaissance Man of the avant-garde, his prolific skills having manifested with equal success in diverse media: sketches and paintings, eel animation, paint of film, live-action films, essays and kinetic sculpture. Always the innovator, he has never bound himself to one mode of expression, choosing instead that which best suits his creative need.

Len Lye‘s Greenwich Village loft is an airy workshop, filled with the tools of the artist’s trade: machine saws, diagrams, models of projected works, and several silvery kinetic pieces glistening in the summer afternoon’s light. Len Lye himself is the Renaissance Man of the avant-garde, his prolific skills having manifested with equal success in diverse media: sketches and paintings, eel animation, paint of film, live-action films, essays and kinetic sculpture. Always the innovator, he has never bound himself to one mode of expression, choosing instead that which best suits his creative need.

For more than 50 of his 75 years he has pursued his quest of motion composition. As a teenager in Wellington, New Zealand, he had his first glimpse of the potential of this art form while delivering newspapers at sunrise. His attention was caught by the movement of clouds and he began to ponder creating artificial clouds to achieve that same quality of motion. “I thought then and there, ‘Why clouds? Why not try to compose motion yourself? — compose motion!”

After this “revelation”, he found the idea was not so easy to implement. “I tried to control motion, and I nearly broke my back. Christ, how do you? So I worked out shafts and handles that could be turned and stuck through shafts so the turning shaft could turn the particular stuff you’d stuck to it; and it was a crazy kind of attempt to control motion and compose it. I was having a ball nevertheless.”

Hoping to learn more about film, Lye moved to Australia in 1922, because New Zealand had no cinematic equipment. He worked at a Sydney studio that made animated advertising shorts. “I learned animation in Sydney, not too much because I was doing storyboards. But I took the job just to be around where people were handling film, just to see.”

Here he chanced upon the concept of “cameraless animation”: “I didn’t invent scratching on film. I saw some guys that had made some marks on it and I rather liked the way they went (through the projector) wiggling like that, you see. I scratched a few feet of film myself, so I kept that in the back of my mind. And then I saw something like it again from a German film crowd. I think it was also some kind of scratching that they did on film. I kept that in mind too.”

Here he chanced upon the concept of “cameraless animation”: “I didn’t invent scratching on film. I saw some guys that had made some marks on it and I rather liked the way they went (through the projector) wiggling like that, you see. I scratched a few feet of film myself, so I kept that in the back of my mind. And then I saw something like it again from a German film crowd. I think it was also some kind of scratching that they did on film. I kept that in mind too.”

These experiments inspired him to adapt his own kinetic works to cinematic technique: “I suddenly realized that films had cuts and sequences. Editors can chop it where they want to. So, instead of having handles and shafts to control motion, I could just swing (objects) on a string or hold them in a black velvet glove against black velvet or whatever; you could really control and make things happen in terms of sequential motion.”

The Russian Revolution had at first created an amazingly fertile environment for the arts, and for the first time film was being considered from an artistic rather than a commercial viewpoint. Later came barbaric suppression. Lye originally planned to travel to Russia, where he hoped to get a job with the Meyerhold Theatre. He worked his passage from Sydney to London on the White Star liner EURIPEDES as a stoker, arriving in 1926. Some fortunate events enabled him to remain in London to work on his first film, TUSALA VA. “I got all sorts of fabulous help that nobody would get now. For example, as a kind of caretaker, I got a rent free barge to work on, plus the use of part of a studio to which the barge was moored on the Thames. I got a promise from the first film society in the world (London Film Society) that they would pay for the photography. And so I settled down for two years worth of animation drawings.”

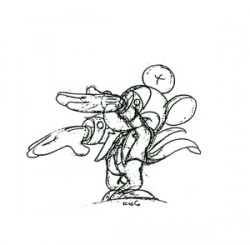

One of Lye’s early stylistic influences was primitive African and South Seas tribal art. “When I first came to London I didn’t quite know what sort of imagery would carry my figures of motion. I had lived in Australia and often wondered what on earth an Aussie ‘aboe witchitty grub’ dance looked like. To get the spirit of the imagery I also imagined I was myself an Australian aboriginal who was making this animated ritual dance film.” The articulated grublike forms in TUSALA VA are reminiscent of designs on aboriginal shields, but they are dynamic moving forms. The animation was painstakingly tedious. “These goddam grubs were animated sideways, like cogs in a bicycle chain. Each cog had to be animated separately. And there were about 20 of these bloody cog-links, they all had to be animated. Why the hell I picked on that I don’t know. Well, I just plodded on, about 16 hours a day; it turned out to be both the slowest motion and the slowest animation on God’s earth!”

TUSALA VA was received rather coolly after its 1928 premiere. “Except for the art critic Rogar Fry, there was just a big silence, a complete and utter silence.” Lye found himself without the means or the support to produce another film by eel animation, and he began to consider animating without a camera, recalling his Australian experiences. “I had already used up all my goodwill stuff with the Film Society. I didn’t have much spare cash and I used to go out to some friends in Baling Studios, London, and hang around — anything to get a job in films. I used to get the old n.g. sound takes, that is, clear film with just a skinny track on one side. I would then scratch and paint and mess around with these bits of film. I would join them together and take them up the GPO Film Unit where I had some friends and run it. All this was done under the counter, you know, on lunch hours.

“I hit some marvelous effects (with) wet paint on a strip of clear film; for instance, you take an ordinary fine tooth comb and just wriggle it as you go down the length of film in the wet paint and it makes a lot of striated wavy lines. So you run it. With all these fancy abstract designs going on, the film had a very peculiar abstract quality. I was very taken by it, but didn’t have much chance of developing it.”

With the help of a composer named Jack Ellit whom Lye had met in Australia (“he was the only fellow there of the whole lot of people I knew who had any understanding of contemporary art”), he ran his film to a catchy recording of a Cuban beguine. He presented it to John Grierson and Alberto Cavalcanti at the British Government’s Post Office Film Unit. He suggested they add some slogans to the end of it. Then, with the help of Ellit, he synchronized his painted film and turned it into a public service film; and so COLOUR BOX was released in 1935, informing delightful audiences about new low parcel post rates. “A Utopian bit of public service,” thinks Lye.

The success of COLOUR BOX resulted in subsequent films for the GPO: RAINBOW DANCE (1936), TRADE TATTOO (1937), and MUSICAL POSTER ttl (1939); as well as several advertising films: KALEIDOSCOPE (1935), for Churchman’s Cigarettes and COLOUR FLIGHT (1939) for Imperial Airways. All these films have in common the abstract “cameraless” technique used in COLOUR BOA’as well as an infectious synchronized score taken from classic jazz and Latin recordings.

The success of COLOUR BOX resulted in subsequent films for the GPO: RAINBOW DANCE (1936), TRADE TATTOO (1937), and MUSICAL POSTER ttl (1939); as well as several advertising films: KALEIDOSCOPE (1935), for Churchman’s Cigarettes and COLOUR FLIGHT (1939) for Imperial Airways. All these films have in common the abstract “cameraless” technique used in COLOUR BOA’as well as an infectious synchronized score taken from classic jazz and Latin recordings.

TRADE TATTOO is Lye’s most ambitious film (“That one’s got to be the most complex film ANYBODY’S ever done”). Lasting but six minutes on screen, it employs some of the most sophisticated editing, montage and processing effects yet seen. Using black-and-white footage from GPO documentaries, Lye combines stencilled patterns, titles and animated effects to form a brilliant montage. Each of the four layers of images that make up the final print had to be exposed three times via the old 3-color Technicolor process, requiring a total of 12 separate processes to arrive at the final color print (“the lab went crazy”). In addition, the footage was tightly edited, employing jump cuts and color reversal to synchronize with the highly percussive Rhumba and Conga beat of the score; once again, Lye was assisted by Jack Ellilt as music director. As one can imagine, the total effect is startling. Even today, some 40 years after its conception, its avant-garde approach still seems fresh and contemporary, capable of rousing an audience to cheers.

Len Lye turned his hand to live action films, directing several shorts for the GPO. In 1944, he was invited to America to direct films for the “March of Time”. Although his 1958 short abstract film FREE RADICALS won the Silver Medal at the Brussels World’s Fair, Lye began devoting more of his time to kinetic sculpture. “My type of film, which is a short film, might take me eight months; and it’s very definitely fine art, not folk art in any shape or form. I take eight months to make five minute’s worth of film. Nobody is going to pay me for any of those eight months. And in any case, it’s a pain in the neck to have a five-minute film. How’s it going to be laced up and tied in with the rest of the program? People go to a movie house to see a program of at least ninety minutes, and they couldn’t care less whether they miss a five-minute fine art job. So my films were a complete anomaly.”

Len Lye turned his hand to live action films, directing several shorts for the GPO. In 1944, he was invited to America to direct films for the “March of Time”. Although his 1958 short abstract film FREE RADICALS won the Silver Medal at the Brussels World’s Fair, Lye began devoting more of his time to kinetic sculpture. “My type of film, which is a short film, might take me eight months; and it’s very definitely fine art, not folk art in any shape or form. I take eight months to make five minute’s worth of film. Nobody is going to pay me for any of those eight months. And in any case, it’s a pain in the neck to have a five-minute film. How’s it going to be laced up and tied in with the rest of the program? People go to a movie house to see a program of at least ninety minutes, and they couldn’t care less whether they miss a five-minute fine art job. So my films were a complete anomaly.”

Nevertheless, Len Lye is still deeply involved in the creation of a new iconography, encompassing all the arts — a new understanding of the relationship mankind, myth, and creativity have in the scheme of life. “I think Art is the only way you can isolate the creative essence of humanity. This essence, like happiness, is individuality. Civilizations and religions may fall down the drain, but their arts remain. It takes the avant-garde to best symbolize the vitality of creativity. There are a lot of great parallels between great, or everlastingly evocative, happiness and great art. This relationship is mainly about value — human value, and it can teach us how to get the most out of ourselves, and life, that we can.”

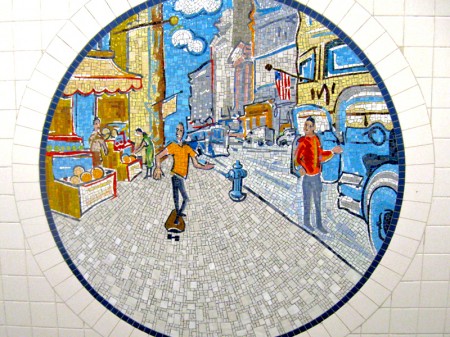

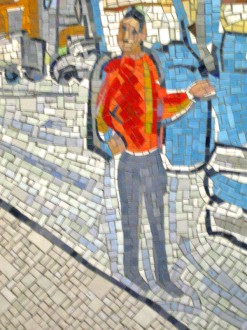

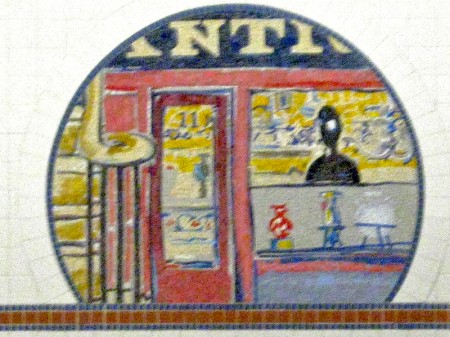

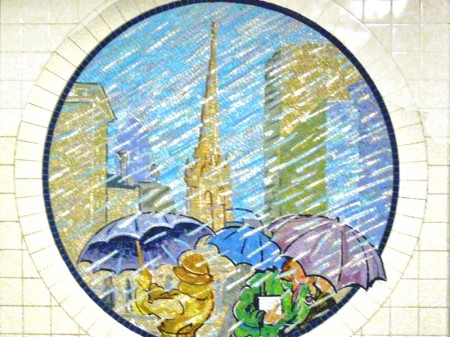

Photos:

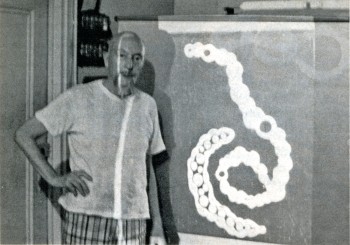

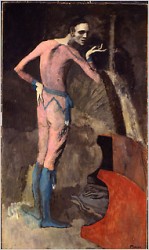

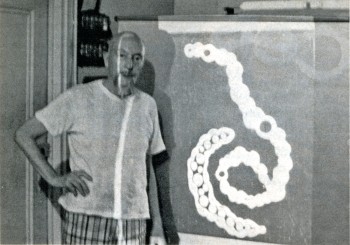

1. Len Lye and a slide from Tusalava (1928) (Photo by John Canemaker)

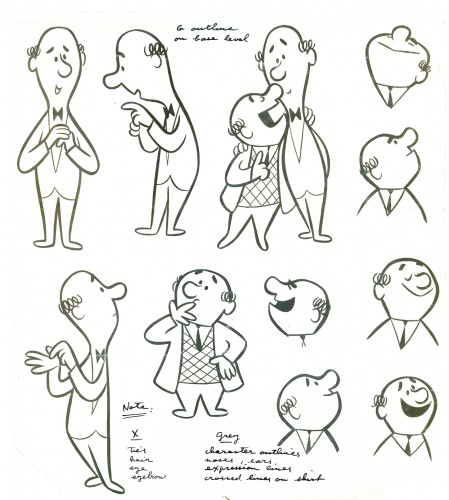

2. Trade Tatoo by Len Lye (Courtesy of Cecile Starr)

3. Rainbow Dance by Len Lye (Courtesy of Cecile Starr)

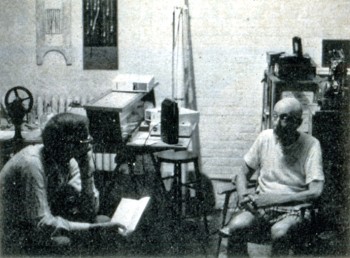

4. Joseph Kennedy (L) interviews Len Lye (photo by John Canemaker)

_____________

Joseph Kennedy is a New York City schoolteacher and a freelance writer. He has taught film history at Regis High School and he reviews films for Film news.

The magazine gave the above short bio about Mr. Kennedy in the Contributors column. Joe is a friend, and I am aware of how limited this makes his work seem (given that it was written in 1977.) He subsequently became a public relations executive and now has his own corporate communications practice; he worked with John Canemaker and Peggy Stern on The Moon and the Son and Chuck Jones: Memories of Childhood.

There is more information about Len Lye at several websites.

The Govett-Brewster gallery gives some good information about the man and his work.

Senses of Cinema offers an extensive bibliography of books and articles about the man.

Several of his film are available on YouTube (of course) in slightly degenerated versions:

Color Box

Swinging the Lambeth Walk

Particles in Space

Kaleidescope

I had a job. It paid $10 less than unemployment. I was a runner for the company. This meant I would help out editing as much as I could (they were doing a lot of work for ABC films.) My first job was to cut the commercials out of 120 episodes of The Smokey the Bear cartoon shows that were going to be sent to South America. By the end of that day I knew how to hotsplice, and my wrists were sore.

I had a job. It paid $10 less than unemployment. I was a runner for the company. This meant I would help out editing as much as I could (they were doing a lot of work for ABC films.) My first job was to cut the commercials out of 120 episodes of The Smokey the Bear cartoon shows that were going to be sent to South America. By the end of that day I knew how to hotsplice, and my wrists were sore.