Yesterday I posted this very same article by giving the PRINT Magazine layout. Today I offer an alternate version, since I think it’s an important piece, wherein the text would be html and the illustrations could be posted larger. Hence, I’ve decided to post it twice, for whatever that’s worth. At least it allows me to keep it running for second day.

.

.

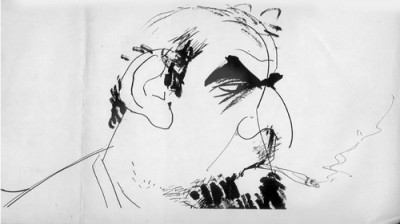

by John Canemaker

Animation innovator, John Hubley was slated to design and direct a film version of the Broadway hit, Finian’s Rainbow. But this was the fearful 50s and the witch-hunting zeal fo the time doomed the project. All that remains are 400 storyboard sketches which recently surfaced and are sampled here.

.

On January 10, 1947, the musical Finian’s Rainbow opened on Broadway to rave reviews, precipitating a successful run of 725 performances. In the fall of that same year, the U.S. Congress-approved House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began a long-running show of its own: the official sanctioning of an “Inquiry into Hollywood Communism.”

On January 10, 1947, the musical Finian’s Rainbow opened on Broadway to rave reviews, precipitating a successful run of 725 performances. In the fall of that same year, the U.S. Congress-approved House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began a long-running show of its own: the official sanctioning of an “Inquiry into Hollywood Communism.”

Amid the wreckage of lives and careers cut short during a decade of insidious HUAC-inspired fear and persecution were numerous film and TV projects fated never to see completion, including a feature-length animated cartoon version of Broadway’s Finian’s Rainbow.

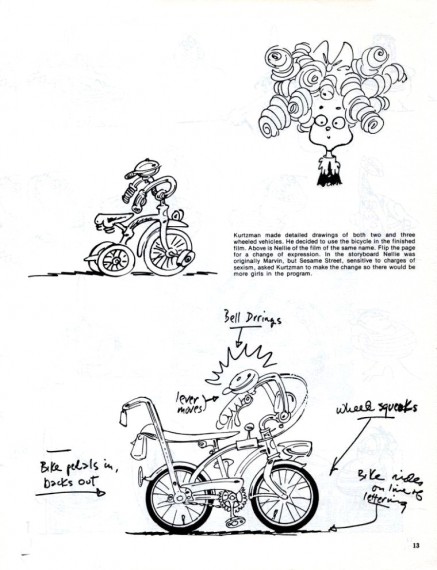

Information about this intriguing production (abruptly halted in February 1955) has been scant; in Euclid tiled Drawings: The History of Animation (Knopf, New York, 1989), Charles Solomon mentions Finian’s as part of the career of John Hubley, the project’s director/designer: “Some animators believe Hubley’s politics were the source of many of the problems that surrounded his ill-fated effort to make an animated feature based on the

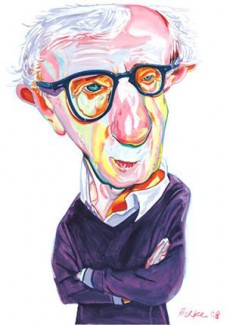

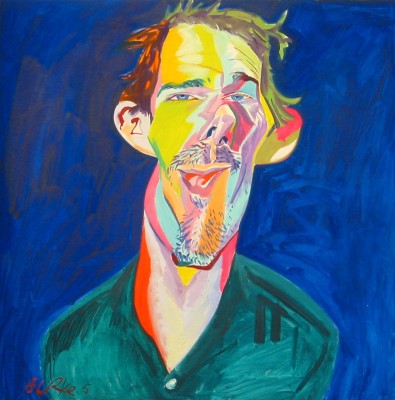

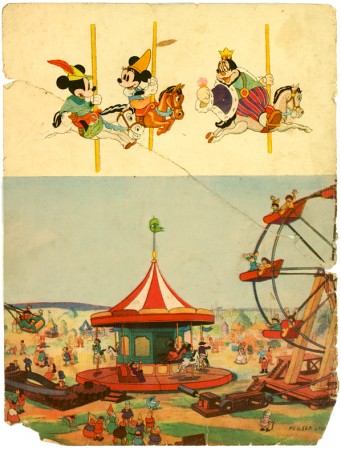

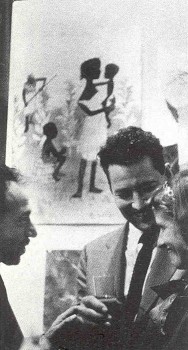

Gregorio Prestopino (L) one of ___ musical Finian’s Rainbow.”

many art directors who worked

on the animated Finian’s Rainbow

talks with John & Faith Hubley

Within the animation industry, there have been rumors of an inspired Hubley-designed color storyboard (alleged to be lost), and of a “dream” soundtrack recording (never publicly released), featuring a stellar cast that included Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Oscar Peterson, Barry Fitzgerald, Jim Backus, David Burns, and two stars from the original Broadway cast, David Wayne and Ella Logan.

Recently, over 400 sketches from the Finian’s storyboard surfaced after nearly four decades of careful storage by Fred J. Schwartz, president of the film’s financing company; in this issue, PRINT is publishing examples of artwork from the animated Finian’s Rainbow for the first time ever. Interviews with Schwartz and other survivors of the project led this writer to a copy of the director’s original script and a reel of the now-legendary soundtrack recording. A detailed history of the “lost” film follows, making it possible to conclude that Finian’s Rainbow would have been an important con-tibution to the history of animated features, opening up the Disney-dominated, child-oriented genre to new sophistication in content and design.

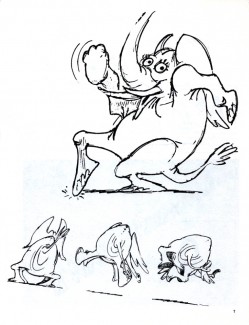

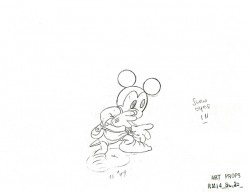

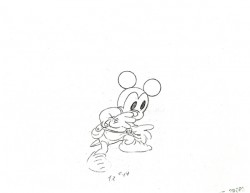

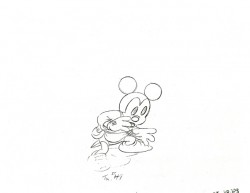

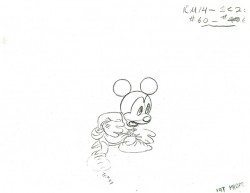

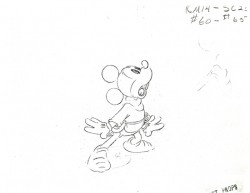

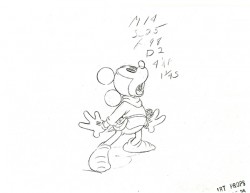

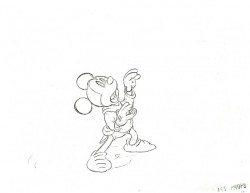

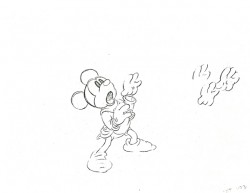

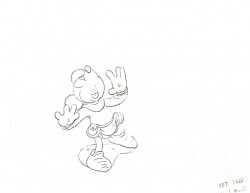

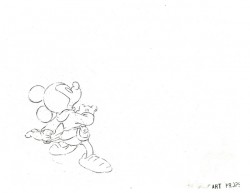

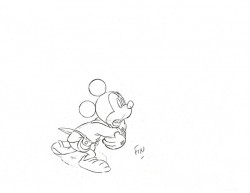

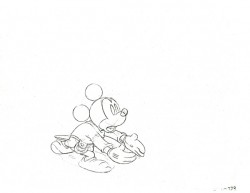

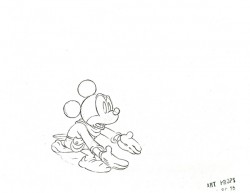

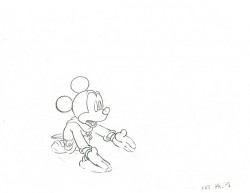

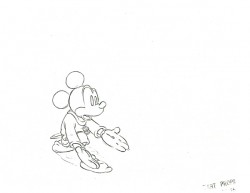

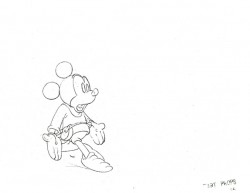

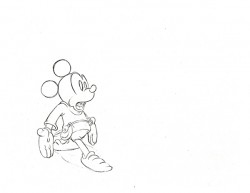

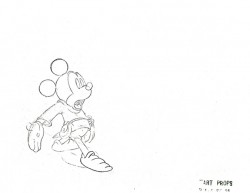

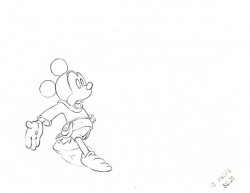

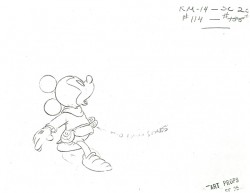

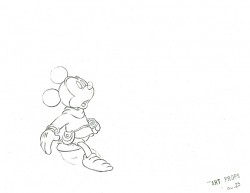

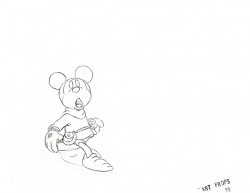

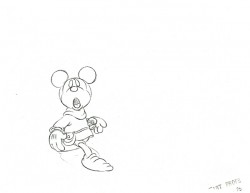

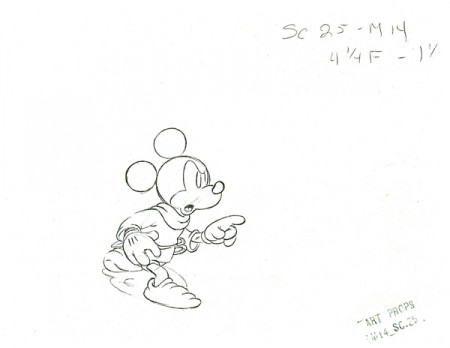

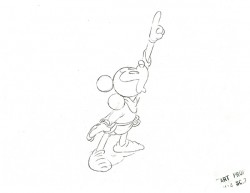

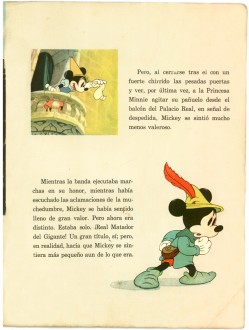

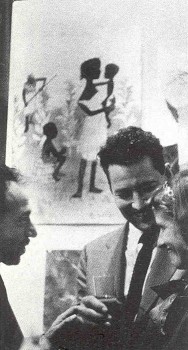

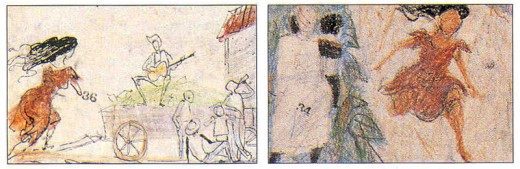

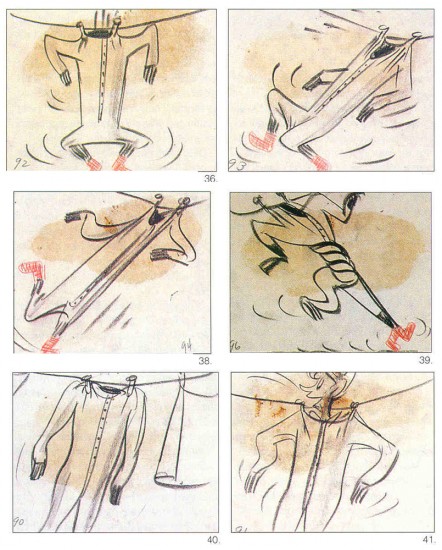

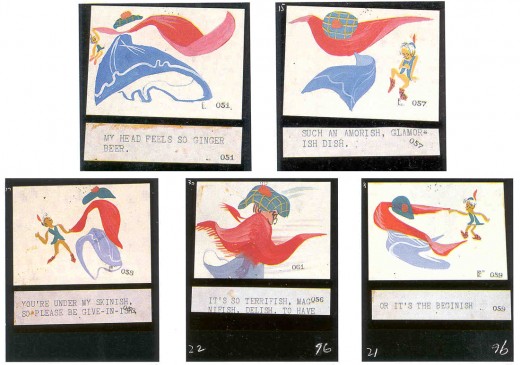

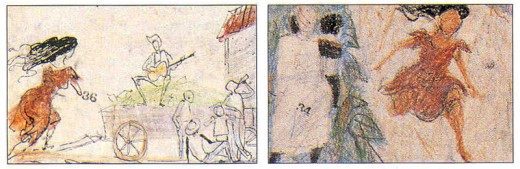

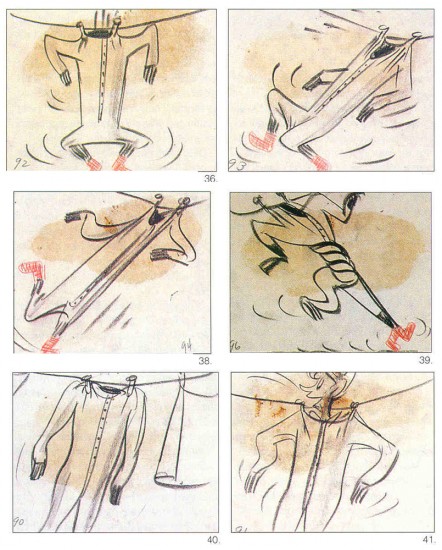

A sequence of color story continuity sketches by John Hubley for the

musical number “Something Sorta Grandish” sung by the love-struck

leprachaun Og as he dances with anthropomorphic laundry. .

Animation was the medium chosen to bring

Finian’s Rainbow to the screen simply because Hollywood’s live-action studios were reluctant to take on the property. (Eventually, in 1968, Fred Astaire starred in a leaden live-action film version directed by Francis Ford Coppola.) “The motion picture industry refused to make a movie of this smash musical because of its story content,” says Michael Shore, the entrepreneur who started the ball rolling toward an animated production in 1953. The show’s composer, Burton Lane, agrees: “The studios were a little fearful of the subject of racial discrimination.”

.

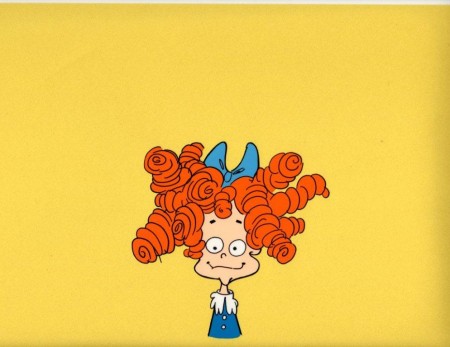

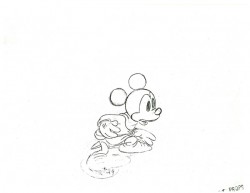

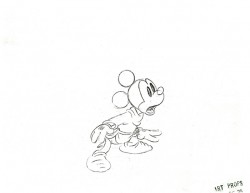

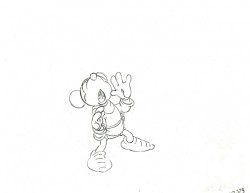

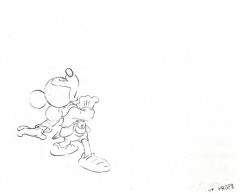

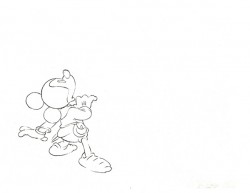

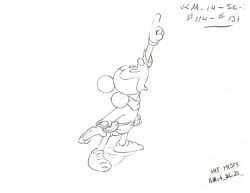

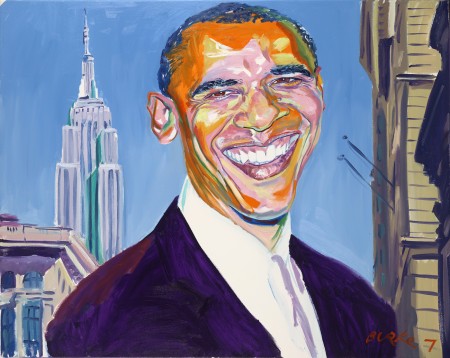

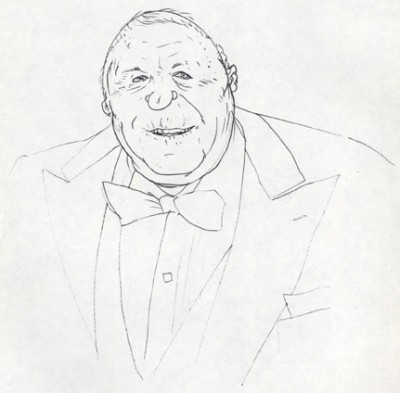

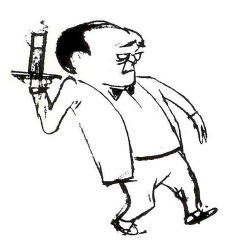

Finian’s Rainbow begins in Ireland, where wily old Finian McLonergan steals a pot of gold from the leprechaun Og. Finian travels with his daughter, Sharon, to America’s Rainbow Valley, a rundown tobacco plantation near Fort Knox, worked by black sharecroppers, where Finian believes the “peculiar nature of the soil lends an additional magi cal quality to gold.” He leases a parcel of land to bury the gold from Woody Mahoney and his sister, Susan the Silent, who dances to communicate (“foot-talkin”‘). Woody and Sharon fall in love. The tiny land parcel is also coveted by Judge Rawkins, a wealthy Southern bigot (“My family’s been having trouble with immigrants ever since we came to this country!”), who goes ballistic when a geologist discovers “an amazing concentration of gold” on the property. In the meantime, the leprechaun Og, who followed Finian to Rainbow Valley, is slowly becoming mortal as a punishment for losing the gold; he helplessly falls in love with both Sharon and Susan. Judge Rawkins attempts to dispossess Finian with a ___A color character model of

Finian’s Rainbow begins in Ireland, where wily old Finian McLonergan steals a pot of gold from the leprechaun Og. Finian travels with his daughter, Sharon, to America’s Rainbow Valley, a rundown tobacco plantation near Fort Knox, worked by black sharecroppers, where Finian believes the “peculiar nature of the soil lends an additional magi cal quality to gold.” He leases a parcel of land to bury the gold from Woody Mahoney and his sister, Susan the Silent, who dances to communicate (“foot-talkin”‘). Woody and Sharon fall in love. The tiny land parcel is also coveted by Judge Rawkins, a wealthy Southern bigot (“My family’s been having trouble with immigrants ever since we came to this country!”), who goes ballistic when a geologist discovers “an amazing concentration of gold” on the property. In the meantime, the leprechaun Og, who followed Finian to Rainbow Valley, is slowly becoming mortal as a punishment for losing the gold; he helplessly falls in love with both Sharon and Susan. Judge Rawkins attempts to dispossess Finian with a ___A color character model of

phony writ condemning the sharecroppers’ dwellings; but ____“himself,” Finian McLonergan,

when Sharon wishes (inadvertently over the magic gold) that_the film’s protagonist who was

Rawkins was in the sharecroppers’ shoes, his skin promptly __voiced by Barry Fitzgerald.

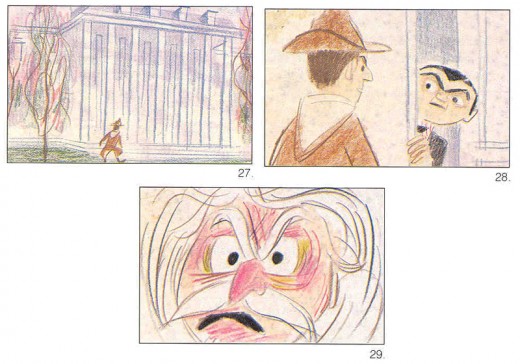

turns black.

The reviews for the Broadway production lavishly praised the performers, Michael Kidd’s choreography, the sets and lighting by Jo Mielziner, Burton Lane’s music, and E. Y. (Yip) Harburg’s lyrics (the show’s hit songs include “Old Devil Moon,” “How Are Things in Glocca Morra?,” “Look to the Rainbow,” and “If This Isn’t Love”), but they were less glowing about the book, which some critics faulted as an uneasy mix of fantasy and reality.

“Among other things,” wrote Richard Watts, Jr., in the New York Post, “Finian’s Rainbow is equipped with what may well be the most elaborate plot since War and Peace. Taking in its stride handsomely diversified elements from pseudo-Irish mythology, complete with an oversized leprechaun and a mystic pot of gold, to left-wing social criticism, embracing sharecroppers, the poll tax, anti-Negro senators, atomic energy, the gold at Fort Knox, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the economic future of mankind, the book mingles the authors’ imagination with their politics amid much abandon…. If some of the political comment were just a little less blatant, the plot just a bit more inventive… the tale of the leprechaun’s mission to America would have been even happier.” Brooks Atkinson of the New York Times found the “stubborn shot-gun marriage of fairy-story and social significance… not altogether happy. The capriciousness of the invention does not last throughout the evening.”

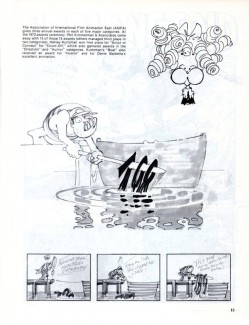

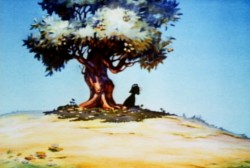

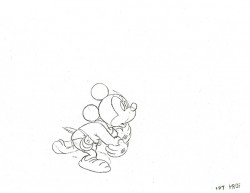

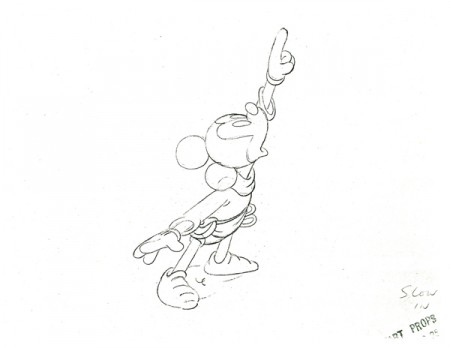

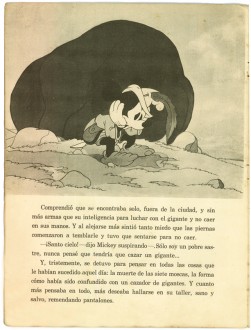

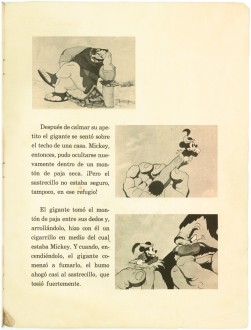

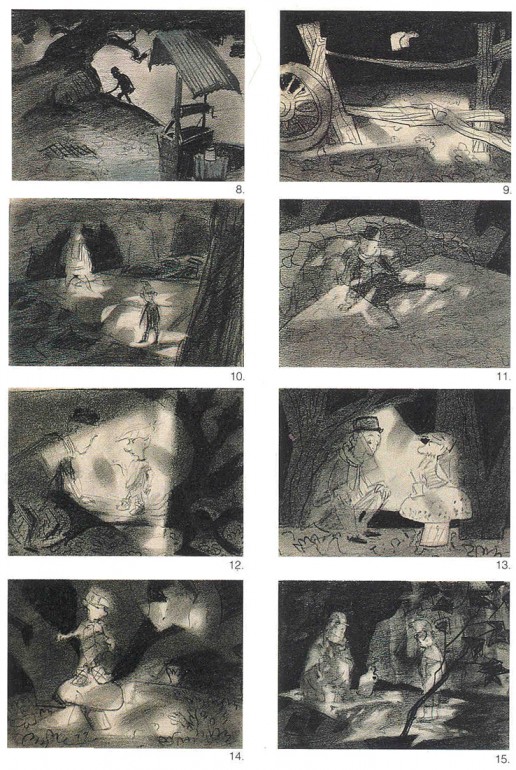

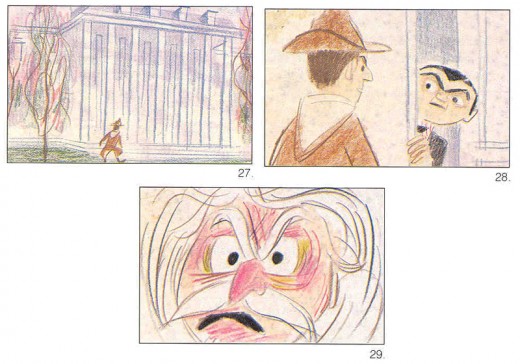

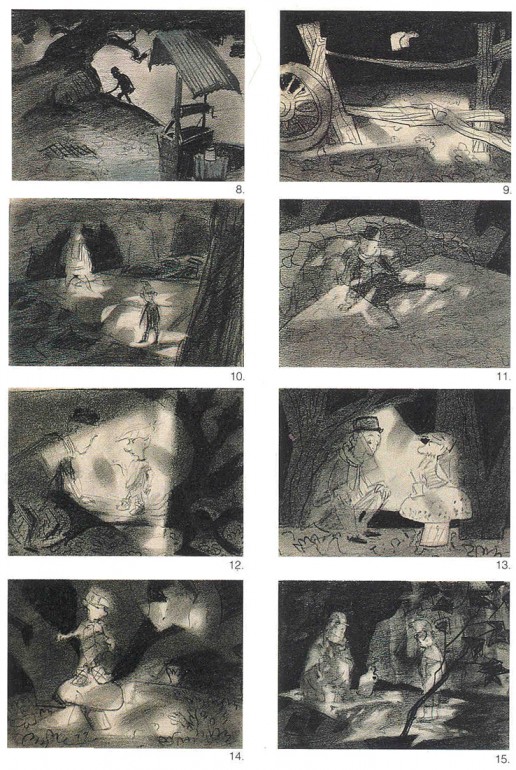

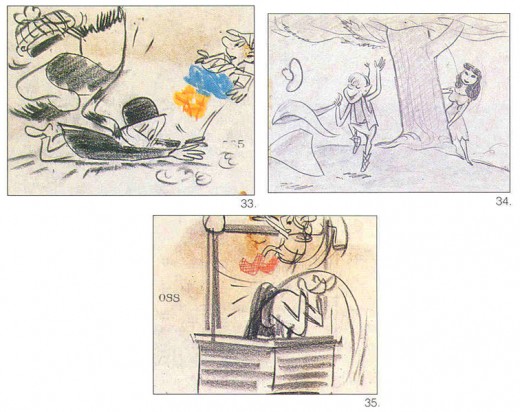

Exquisite charcoal story-continuity sketches, delicately rendered

by John Hubley, depict a sequence of moonlit magic wherein Finian

buries the stolen crock of gold – on which the plot of Finian’s Rainbow

hinges – and is confronted by Og. The voice of Og was supplied by David Wayne,

who originate the role in the Broadway production.

.

“It’s heavy-handed,” says Michael Shore, now 75. “I told Yip [co-author of the script with Fred Saidy] what bothered me about the property. It tells you that a terrible person turns black because he’s so bad, and then redeems himself and they reward him by making him white again.

“It occurred to me the story line could be made more palatable if it were done in animation. I had met Hubley. I was in the advertising business and had done some commercials with him. He was a towering genius! I made a deal with Yip to option Pinion’s for $10,000.1 underwrote the pre-production development of the property and paid Hubley to single-handedly do this remarkable storyboard. The story line became lighter and more acceptable.”

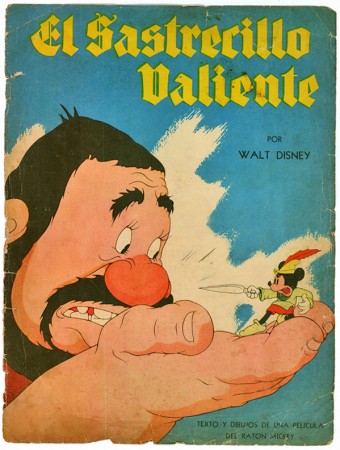

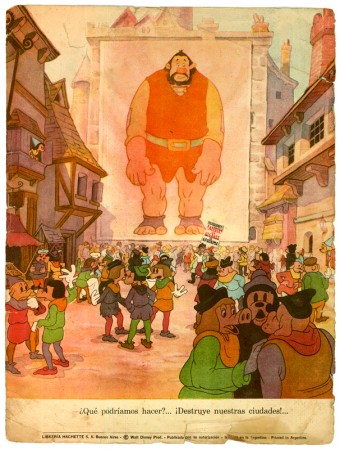

John Hubley (1914-1977) began his career in animation at age 22 at the Walt Disney Studio painting backgrounds for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). [See PRINT, November/December 1981: "The Happy Accidents of the Hubleys."] He was an art director on Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), Dumbo (1941), and Bambi (1942) before participating in the acrimonious workers’ strike at Disney’s in 1941.

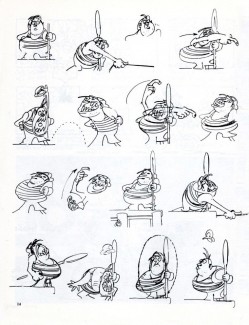

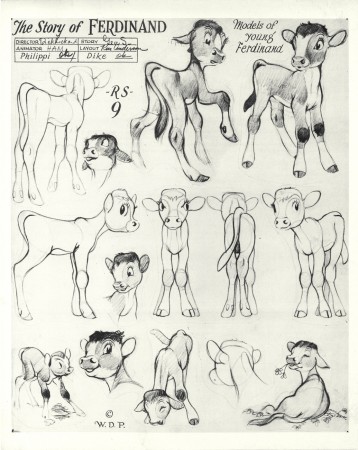

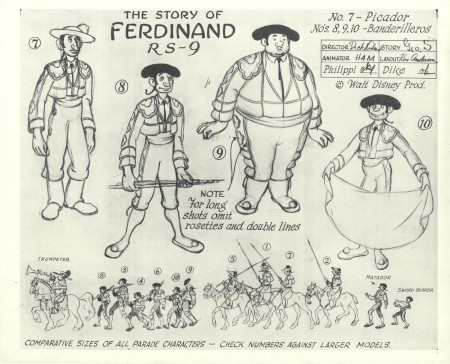

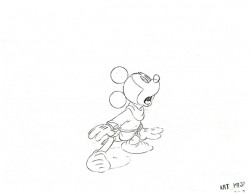

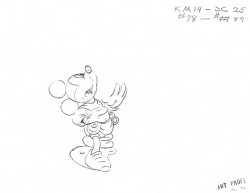

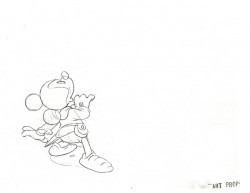

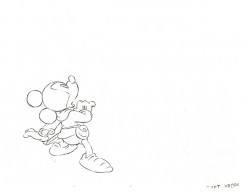

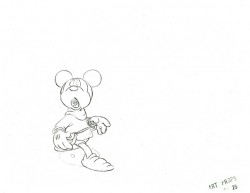

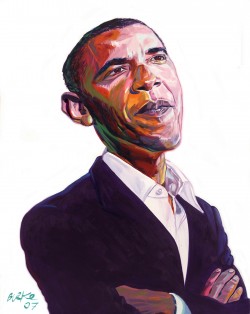

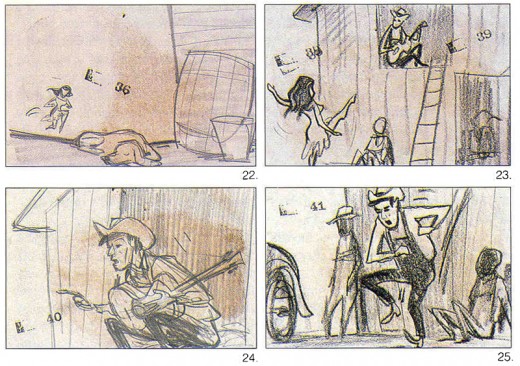

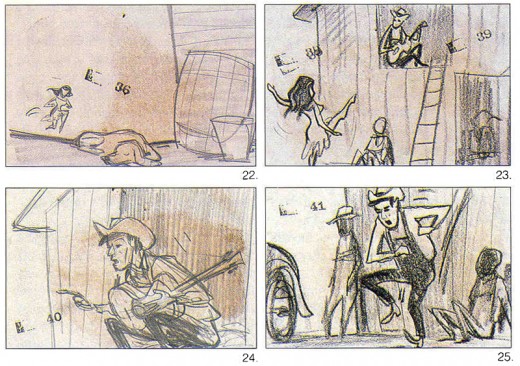

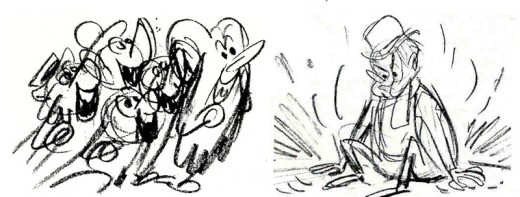

Color character sketches of Buzz, henchman and gofer for Judge Billboard Rawkins,

the story’s racial villain; a US geologist, and Howard, Judge Hawkin’s butler.

Finian’s Rainbow is an odd combination of fey fantasy and social commentary. .

Walt Disney, who took the strike as a personal attack, found the opportunity to exact revenge on his renegade employees when he testified as a “friendly witness” before HUAC on October 24, 1947. He painted them bright Red. The strike, said Disney, was organized by “a Communist group trying to take over my artists and they did take them over.” Disney named names, including that of David Hilberman. Hilberman was a partner in the formation of a new animation studio, United Productions of America (UPA), staffed by dissident Disney artists, one of whom was John Hubley.

UPA’s design sensibility veered far from Disney naturalism into a modern art esthetic, and Hubley, from 1942 to 1952, was the studio’s most innovative supervising director. “In the early days,” he recalled many years later, “it was Picasso, Dufy, Matisse who influenced the drive to a direct childlike flat simplified design, rather than a Disney 18th-century watercolor. I also always had a terrific rebellion against the sweet sentimental chipmunks and bunnies idiom of animation, saying, ‘Why can’t these be human caricatures and get that same vitality in animation that still drawings have?’”

Earl Klein, an artist who worked with Hubley on storyboards and backgrounds for TV  commercials in the ’50s, recalled in a 1990 interview with animation historian Michael Barrier that Hubley would ask his animators to volunteer to return to the studio in the evening. “[He] would play … a particular kind of music and have the animators go like a conga line around and around the room, listening to the music and trying to feel the rhythm and act out the emotions…. [He] said he wanted to break them away from the old established routine, the rubbery action movements that were so prevalent in those days… to influence them to be more creative in how they would see the human body in terms of animation.”

commercials in the ’50s, recalled in a 1990 interview with animation historian Michael Barrier that Hubley would ask his animators to volunteer to return to the studio in the evening. “[He] would play … a particular kind of music and have the animators go like a conga line around and around the room, listening to the music and trying to feel the rhythm and act out the emotions…. [He] said he wanted to break them away from the old established routine, the rubbery action movements that were so prevalent in those days… to influence them to be more creative in how they would see the human body in terms of animation.”

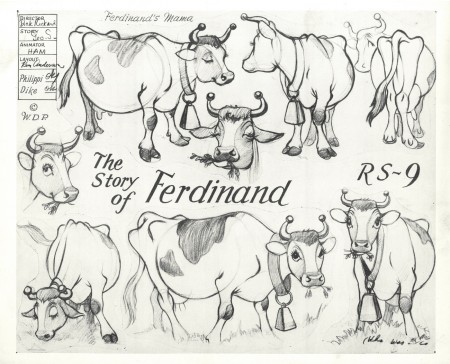

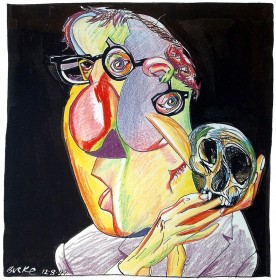

Colored pencil story sketches by Gregorio Prestopino

.

At UPA, Hubley co-created Mr. Magoo, supervised the studio’s first Academy Award-winning short, Gerald McBoing Boing (1951), and was nominated for an Oscar for his sassy stylized design and direction of Rooty Toot Toot (1952). “McBoing was a huge hit,” said Hubley. “The word started spreading that there was a new look to animation and Disney was finished!”*

Then the withering shadow of HUAC fell across UPA. “The Committee investigators dropped in and wanted the payroll book,” recalls animation director William Hurtz. “They went through names of anyone who worked there, checked some off and gave it to Columbia [UPA's film distributor], who came back and said these people have to be out of the studio or we yank the release. Most of the guys, including Hub, resigned rather than torpedo the studio. Least it could go on and some guys could have jobs. We were all on the Disney strike. I made the motion for the strike. It was a tight little club.”

“John didn’t leave voluntarily. He was kicked out!” comments Faith Hubley, John’s widow, who continues today to produce animated films at the Hubley Studio in New York City. Hubley freelanced for a nerve-racking year in Los Angeles, designing and directing animated TV commercials and, according to William Hurtz, “[making] himself scarce while the HUAC subpoenas were flying around.” Michael Shore was so concerned about Hubley’s mental state when he commissioned Hubley to create the Finian’s Rainbow storyboard in 1953, he ensconced the artist in a rented Sunset Plaza Drive house, “an isolated, beautiful setting with a 360-degree view of Los Angeles, where he could work uninterruptedly.”

“John was in love with Finian’s Rainbow,” says Faith Hubley. “It was to be the work of his life.”

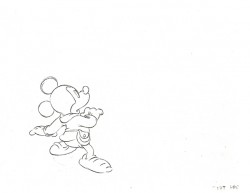

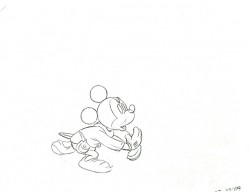

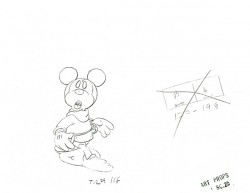

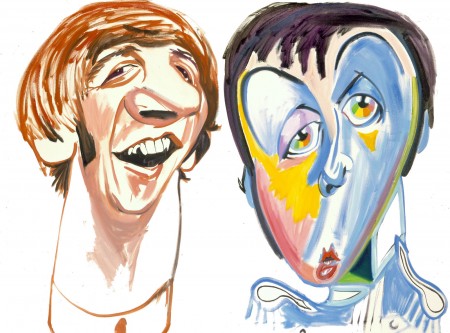

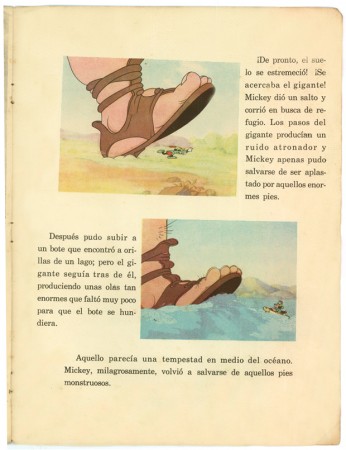

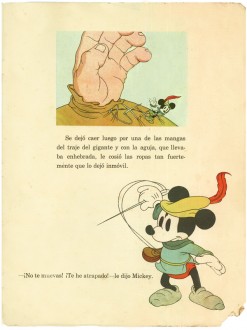

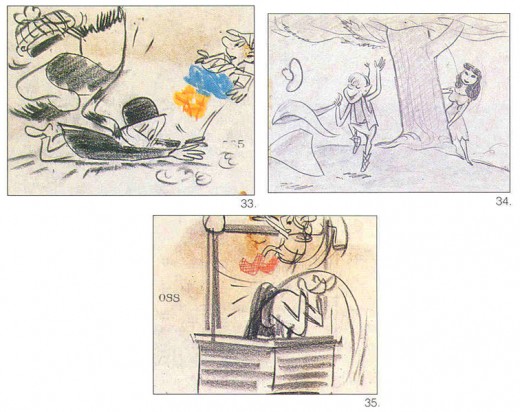

Story sketches (artist unknown) of Susan the silent rushing to tell her brother, Woody,

about trouble in Rainbow Valley, the rundown tobacco plantation located near

Fort Knox, KY. Woody’s voice was provided by Frank Sinatra. .

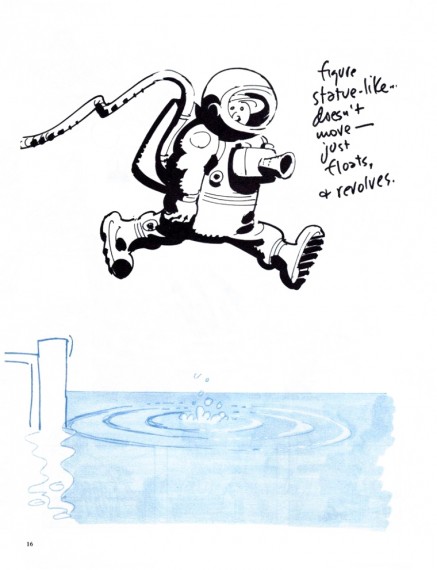

The director’s script and surviving story sketches indicate how Hubley used the medium of animation—in which the impossible is made plausible—to wrest the narrative from the confines of live-action and release it into cartoon fantasy. Preceding the title and credits, for example, Finian McLonergan distracts the leprechaun Og from guarding a crock of gold by releasing a beautiful butterfly, onto which the tiny Og leaps, “soaring off into the misty woods.” As Og gradually becomes mortal throughout the film, eventually experiencing love for two human women, he expresses this new “glow-ish, kind of perculiarish sensation” by appearing and disappearing whole and in part throughout the film, and in one charming sequence, by performing a ballet-like dance with anthropomorphic wash from a clothesline.

Leprechauns aside, most of the cast is human, traditionally the most difficult type of character to animate convincingly. But Hubley caricatures the cast, even the romantic leads (Sharon and Woody), and the exaggeration works within the film’s overall art direction. The resultant visual freedom allows for stylish treatments of potentially deadening song duets: For “Old Devil Moon,” for instance, Hubley’s script notes an “abstract sequence and Boy and Girl symbols dancing with the moon.”

Hubley once stated that his impulse with Finian‘s was to “develop the visual art even further than the UPA films had.” He felt a “need to break through and to play around with more plasticity… to get a graphic look that was totally unique to animation, that had never been

seen before.” Rooty Toot Toot, made a couple of years before Finian‘s, demonstrates Hubley’s superbly imaginative blending of caricatured humans with impressionistic settings. Tender Game (1958), a short he designed three years after Finian‘s, shows a further development of adventurous graphic experimentation using segmented, semi-abstract figures weaving into and out of translucent backgrounds. Michael Barrier once noted that Hubley’s graphic devices “… all serve, in the end, not to explicate ideas but to delineate character… .These films are as much concerned with personality as are the best Disney films… .They have sprung from the same seed, the urge to create new life.”

seen before.” Rooty Toot Toot, made a couple of years before Finian‘s, demonstrates Hubley’s superbly imaginative blending of caricatured humans with impressionistic settings. Tender Game (1958), a short he designed three years after Finian‘s, shows a further development of adventurous graphic experimentation using segmented, semi-abstract figures weaving into and out of translucent backgrounds. Michael Barrier once noted that Hubley’s graphic devices “… all serve, in the end, not to explicate ideas but to delineate character… .These films are as much concerned with personality as are the best Disney films… .They have sprung from the same seed, the urge to create new life.”

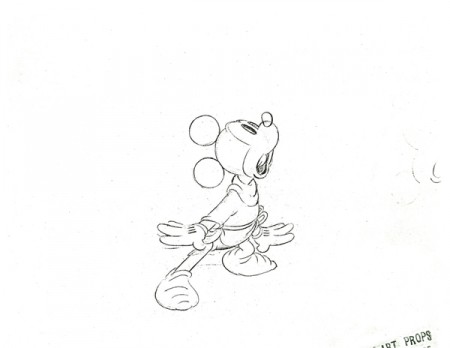

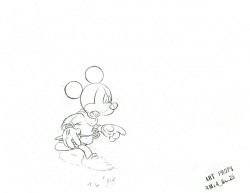

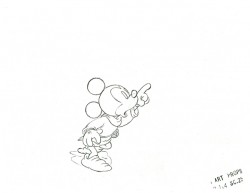

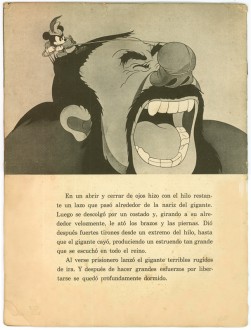

Story sketch samples from a sequence at the colonial estate

of Judge Rawkins. The judge’s voice is that of Jim Backus..

As Hubley continued to work happily on the

Finian’s storyboard, Michael Shore was having “a lot of trouble raising funds. I brought on Maurice Binder, who later became well-known for making film titles, to seek other funding sources while I concentrated on Warner Brothers.”

Binder found the newly formed Distributors Corporation of America (DCA) in New York City, headed by Fred J. Schwartz. “We were intrigued by the project,” recalls Schwartz, now 81, whose father, Abraham H. Schwartz, founded the Century Theater movie circuit and initiated the anti-trust law suit that eventually broke up studio-owned theater circuits. “We made a deal and started to put everything together. We made the deal with Yip Harburg, Saidy, and Lane, who were wonderful people. You enjoyed and loved being with them. We started to make deals with all the artists.”

“When we had the DCA money,” recalls Shore, “we started to put the soundtrack together. I was friendly with Sinatra’s accountant and with Ella Fitzgerald’s manager. Sinatra was wildly excited. It was these two great names in music together for the first time. Then we attracted all the others.”

The dialogue and song tracks were recorded in five sessions in November and December 1954 on the Samuel Goldwyn lot in Hollywood, according to Ed O’Brien, coauthor with Scott P. Sayers, Jr., of Sinatra: The Man and His Music. The Recording Artistry of Francis Albert Sinatra 1939-1992 (TSI) Press, Austin, TX, 1992). “Sinatra was at the apex of his career,” says O’Brien. “He was filming Guys and Dolls [1955], he was in The Tender Trap [1955]. It was right at the beginning of the great Sinatra period at Capitol Records. In February of 1955, he recorded ‘The Wee Small Hours,’ which many consider the greatest ballad album ever recorded.” (Ironically, that is the same date Finian’s shut down.)

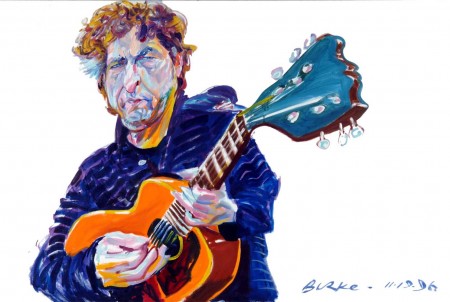

Listening to the surviving sections of the nearly 40-year-old track brings the project to exuberant life. Sinatra is indeed in top form, his voice confident and vital as it combines with Nelson Riddle’s distinctive brass and string arrangements and Lyn Murray’s conducting. Sinatra’s full-out, driving version of “That Great Come and Get It Day” is particularly exhilarating. The improvised “Ad Lib Blues” duet with Louis Armstrong offers one of the few times Sinatra sang “scat.” “I was there at the recording whenTouis Armstrong did The Begat,’ recalls Burton Lane. “The shape of the number was slightly altered to make it work for what Hubley had in mind for how the number would be shot.”

“On December 2, 1954,” says O’Brien, “Sinatra recorded ‘Old Devil Moon’ with Ella Logan [star of the Broadway Finian's], full orchestra, and the Jazz All-Stars: Red Norvo, Ray Brown, Herb Ellis, Oscar Peterson, and Frank Flynn. The vocal runs eight minutes, 20 seconds. There’s a jazz riff in the middle in which Peterson challenged Norvo. It’s extemporaneous and absolutely marvelous!” By contrast, a Sinatra duet with Ella Fitzgerald on “Necessity” swings lightly with only guitar, bass, and drums for accompaniment. The change from big-band arrangements into jazz throughout the film score got full approval from John Hubley, a longtime jazz enthusiast. “I used to go out with him some evenings to listen to live jazz,” recalls Earl Klein. “We went one night to hear Prez Prado. I was very impressed with his knowledge of music.”

Faith Hubley recalls: “Sinatra wrote out the words of Tenderly’ [a song not from Finian's] for Ella, who didn’t know all of them, for a lunch-time improv with Oscar Peterson, Ray Brown, and Herb Ellis.” The extemporaneous song was recorded and used in John and Faith Hubley’s 1958 short, Tender Game, making it the only trace of the Finian’s recording sessions currently available to the general public.

A studio was opened in Hollywood to house the animation crew Hubley began hiring to create additional story sketches, color background concepts, character design models, and animation layouts. “Hub tended to drop something on an artist,” says William Hurtz, “let him explore stuff, see what he came up with. Spent a lot of money that way. Very admirable. Hub spent so much on the track that there was hardly anything left to make the picture. That is a persistent story.”

Among the Finian’s Rainbow crew were production manager Les Goldman, the painter Gregorio Prestopino, and Disney/ UPA alumni Paul Julian, Aurelius Battaglia, Ray Sherwin, and Leo Salkin. “We had more art directors on that film than I can count,” Julian told Michael Barrier in 1986. “Everybody came on hired as an art director….

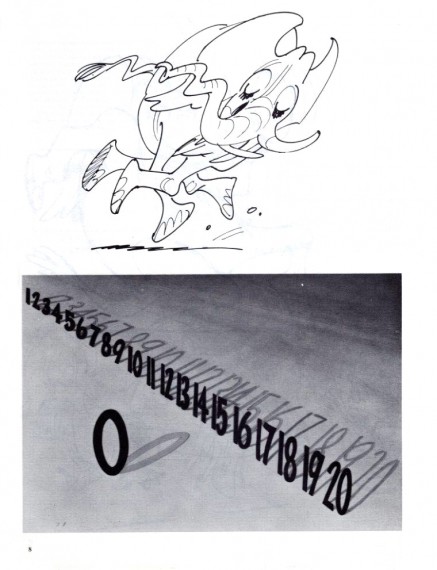

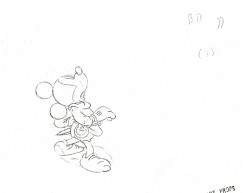

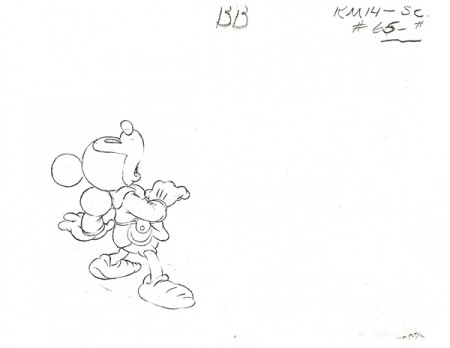

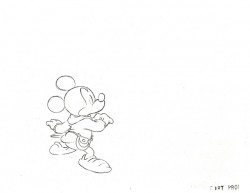

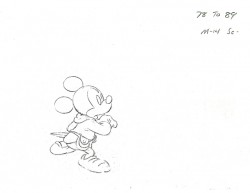

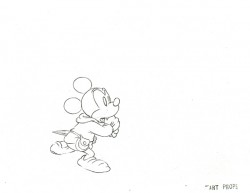

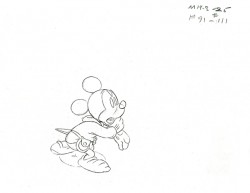

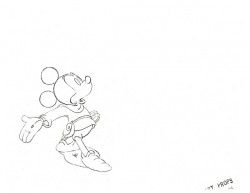

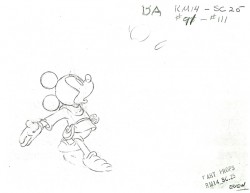

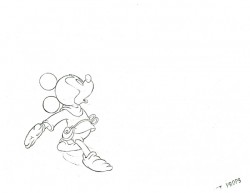

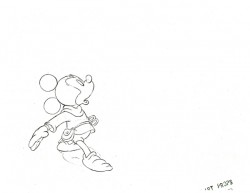

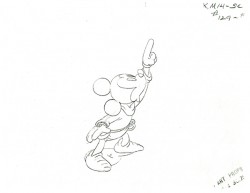

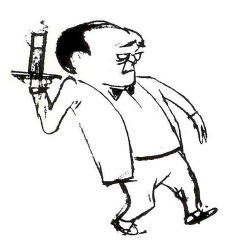

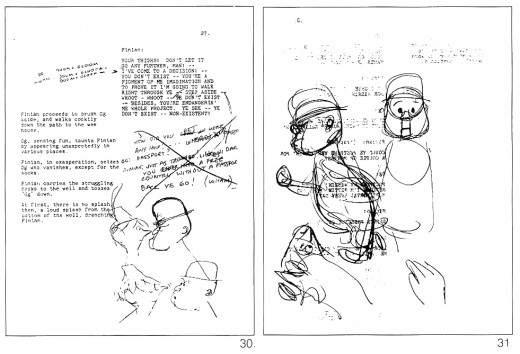

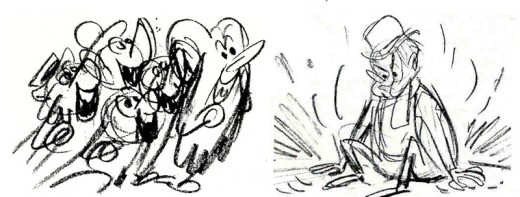

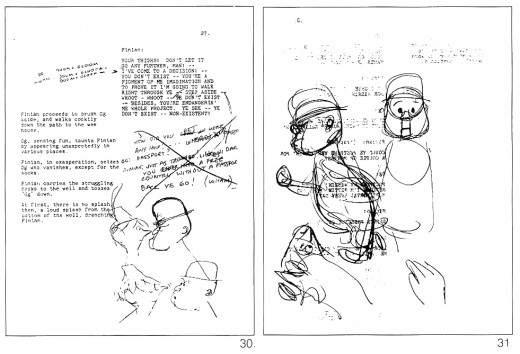

Two pages from director John Hubley’s script contain spontaneous doodles in the margins -

ideas for animation bits such as a nose wiggle for Og and a belligerent walk for Finian.

Finian’s basic shape recalls that of Mr. Magoo, a character co-created by Hubley..

Hubley had put a knife in his teeth and started climbing the rigging. In order to sell the package to the kind of really upstairs talent he wanted, he promised everybody 50 per cent of whatever there was. That is not much of an oversimplification.”

Slated to animate on the film were Bill Littlejohn and Art Babbitt, one of the Disney strike leaders. Work would also be farmed out to animator/Disney striker William Tytla in New York. Anita Alvarez, the original Susan the Silent in the Broadway Finian’s, danced in a reference film shot as an aid for the animators. Maurice Binder prepared a “Leica reel,” a film of the story sketches synchronized to the soundtrack.

According to Earl Klein, Hubley’s easygoing manner made him “hard to work with because he wasn’t very disciplined.” When they worked together on TV commercials, Klein discovered that tight production schedules did not unduly trouble Hubley. “Instead of getting the storyboard out, he would be interested in something else. But then he would come in and work all night long … [and] in the morning … he had a beautiful storyboard that he had just come up with, this wild idea.” Klein feels that “of all the people I worked with in a span of 30 years, John Hubley was probably the most talented . . . most creative person I ever knew… almost a genius. He was a superior designer, also a writer. He understood music and timing beautifully. I’ve seen him direct recording sessions with musicians.”

Faith Elliott, a film/music editor and script supervisor, arrived from New York in the fall of 1954 tb work as John Hubley’s assistant. John and Faith had been friends since the war years in Los Angeles; she saw the Finian’s boards the previous year at the Algonquin Hotel in Manhattan, where Hub-ley was briefly in hiding from the Hollywood HUAC. In 1955, they were married, leading Yip Harburg to comment ruefully that “the only people who got anything out of Finian‘s was you two!”

“There was a lot of tension in the studio,” Faith Hubley recently recalled. “Johnny had a tiny room with a piano and a sofa and an ocean of paper. He’d play the piano and get ideas and noodle around. Then there was that other room where all the people worked. The track was being recorded and edited, layouts were being made. The power situation was very, very complicated. Yip and Burton had a problem with all the jazz. Yip would complain, ‘You can’t hear the lyrics.’” Michael Shore recalls: “We had some trouble with Yip. He kept questioning Hubley’s drawings of a leprechaun. He stuck his nose in everything.” “In a sort of combination of jeers and fears,” Paul Julian recalled to Michael Barrier, “the people who were putting up the heavy loot were totally ignorant of animation, as a working process, and they kept asking to see yesterday’s dailies’ [footage developed overnight].”

“There was a lot of tension in the studio,” Faith Hubley recently recalled. “Johnny had a tiny room with a piano and a sofa and an ocean of paper. He’d play the piano and get ideas and noodle around. Then there was that other room where all the people worked. The track was being recorded and edited, layouts were being made. The power situation was very, very complicated. Yip and Burton had a problem with all the jazz. Yip would complain, ‘You can’t hear the lyrics.’” Michael Shore recalls: “We had some trouble with Yip. He kept questioning Hubley’s drawings of a leprechaun. He stuck his nose in everything.” “In a sort of combination of jeers and fears,” Paul Julian recalled to Michael Barrier, “the people who were putting up the heavy loot were totally ignorant of animation, as a working process, and they kept asking to see yesterday’s dailies’ [footage developed overnight].”

“Johnny was the director with creative control,” says Faith Hubley, “and Johnny was very strong. There was a certain amount of tension about where the picture was going—would it be too advanced for the great American public?”

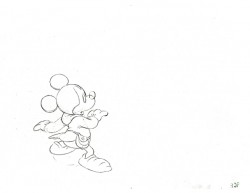

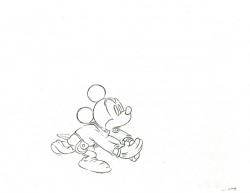

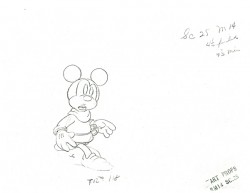

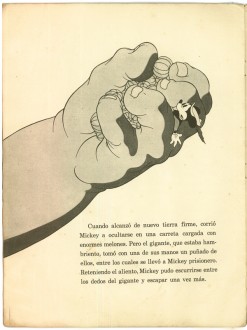

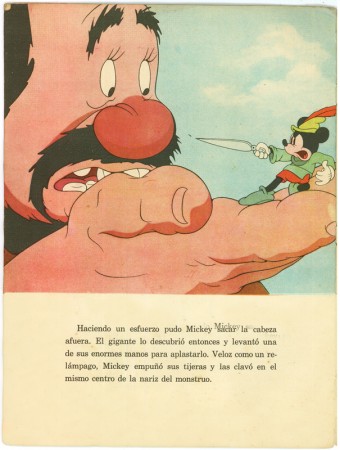

Og pursues Susan the Silent and escapes Finian, who falls down a well,

in a series of rough story sketches by John Hubley..

During this intense, anxious period, Michael Shore, the man who had conceived of the production as animation, had paid for the pre-production storyboard, and had put together elements for the spectacular soundtrack, found himself “on the outside looking in. I couldn’t even get into the office.” Angry, he went to Binder, who said, “Don’t rock the boat.” “I couldn’t bother Yip,” says Shore. “He turned his back on me.” Finally, he confronted Hubley, meeting with him “across from Schwab’s drugstore. I said, ‘I don’t want to bother anybody, but I’m being treated shabbily.’ To my surprise, John was very doctrinaire. He may have had more leftish leanings than I thought. He said, ‘I don’t give a damn. I can only think of the picture. To hell with emotions. I’ve got a job to do!’ I said he was being less than reasonable. This was my project. From day one, I had brought it to a certain point and I was going to re-introduce myself to the project. My lawyer met with DCA and we managed to shut down the production for two days while they negotiated an agreement that acceded to my involvement—a promise to return monies, an assurance of screen credit, and so on. Of course, it turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory.” Earl Klein recalls: “Hubley got so involved with the problems of Finian’s Rainbow that he began to turn a little sour and become unpredictable.”

.

.

“Another pressure,” says Faith Hubley, “was the complicated representative situation. SCG [Screen Cartoonists Guild] was not IA [IATSE: International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees]. It had to be IA, otherwise Finian’s couldn’t play in theaters.” Bill Little-John, who was the first president of SCG, recalls he was told “I’d have to become a member of the IATSE, which had taken over Disney, UPA, MGM, Lantz, Warner’s. SCG still had contracts with the smaller studios that did TV commercials and special projects. I said the studio doesn’t select the representative of choice. It’s up to the employees. Well, that hit the fan. The backers of the film were deeply entrenched with the IATSE element; that got their backs up and created complications.”

Just how involved the IATSE was became clear when Fred J. Schwartz got a phone call from Roy Brewer, leader of the IATSE, chairman of the AFL Film Council, and chairman of the executive committee of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. In A Journal of the Plague Years (Atheneum, New York, 1973), author Stefan Kanfer describes Brewer as one of Hollywood’s toughest “stainless-steel” anti-Communists, a man who “no longer played the ruthless prosecutor,” preferring “the part of father-confessor, guide to the tortured and lorn.” William Hurtz recalls a command visit to Brewer’s office during the UPA purge to “listen to him lecture us on the error of our ways for being duped  by Reds, by associating with Hub and a number of the other guys.”

by Reds, by associating with Hub and a number of the other guys.”

Brewer told Schwartz he thought he was “in trouble. You’ve got a problem. Let’s meet.” The problem turned out to be John Hubley, who Brewer said “is suspect and refuses to appear before the Hollywood Committee. If he doesn’t appear and clear himself, you lose your money, you lose everything.” A shaken Schwartz met with Hubley.

“This was a very distasteful conversation for me, but I had no choice but to go through with it,” Schwartz recalls. “I said, ‘John, I got this call and I have to ask you a question. I have to swallow hard before I ask it. I want you to know I don’t believe in it, but I’m faced with a terrible situation with many individuals at risk.’ I asked, ‘Were you ever a member of the Communist party?’

“He said, ‘No. Definitely not! I will admit that like many other artists in Hollywood, I belonged to some organizations that had high-sounding names and when I found out they were fronts for the Communist party, I left them. That’s as far as I ever went.’

“I said, ‘John, we have $365,000 in the project.’ Forty years ago, that was substantial. I said, There are other people involved. Go before the Committee and clear yourself, so we can go ahead.’ He said, ‘I would be happy to, but Freddy, they’re going to ask me to name other names, and that I won’t do!”

Upon learning of Hubley’s refusal to testify, DCA’s parent company, Century Film, and their lender, Chemical Bank, decided to drop financial support of the film. But Schwartz did not give up. He sought and found $75,000 in backing from RKO, about a third of the amount needed to finish the film. Check in hand, Schwartz again approached Century. The company still refused. “And Chemical Bank said, If your own company turned you down, we can’t lend you the money,” says Schwartz, who with great sadness instructed DCA’s West Coast representative, Milton Pickman, to close the studio.

To the filmmakers, unaware of Schwartz’s desperate month-long search for money, the closing of the studio came with shocking suddenness. “It was electric!’ recalls Faith Hubley. “They impounded everything,” says designer Paul Julian, “including my stopwatch.”

“The banks refused to put up the money and it all fell apart,” says Burton Lane. “The McCarthy era was one of the worst periods. Half of my friends acted with honor and half acted with dishonor, so I gave them up. John Hubley acted with honor.” The blacklist tarred Burton’s colleague Yip Harburg, leading to, among other things, the revoking of his passport and a 12-year gap in his employment as a lyricist for movies. Earl Klein believes that word of a Harburg/Hubley collaboration originally alerted IATSE, and Hubley’s non-cooperation with HUAC doomed the production: “. . . word got around that you weren’t supposed to touch it. It was actually a blacklist and a boycott situation…. [Hubley] was in a position where the lab technicians wouldn’t handle any of… the pencil tests or anything like that. This made it impossible for them to proceed and the project had to be dropped.”

The letdown was enormous for all the parties involved. “My heart ached when it didn’t happen,” says Michael Shore. Paul Julian calls it “tragic.” “A big disappointment,” says Burton Lane. Years later, even Sinatra’s music arranger, Nelson Riddle, commented to Ed O’Brien, “It is a tragedy what happened to Finian’s.”

“What happened to me? Trouble,” says Fred Schwartz. “I was in a terrible position. The company [DCA] went under, but I had to stay with it. I didn’t have to, but I felt it was right because we owed the bank a lot of money. While I wasn’t personally liable, the company was. The bank loaned the money in part because they believed in the venture and had confidence in me. I couldn’t walk away. So I stayed with it for six years till I paid off the bank. My partners both left their jobs. They were angry at the circumstances. One had two small children at the time. You know what that made me feel like?”

“The blacklist was that powerful,” Schwartz continues. “This is an example of what happens when you squelch talent. Which is directly against everything we stand for, such as freedom of speech. This could have been a classic that would live forever.”

“The blacklist should never happen again. It certainly affected the history of animation,” asserts Faith Hubley. “If Finian’s had been finished, we’d have seen wonderful animated films of substance and content.”

HUAC eventually caught up with John Hubley; he testified for two hours and ten minutes on July 5,1956, but refused to name names, invoking his Constitutional privilege under the First and Fifth Amendments. By that time, however, HUAC and the blacklist’s power were fading; the Hubleys moved to New York, and over the years produced a series of personal animated shorts, which eventually garnered three Oscars, among other awards. “It was sad for me that Finian’s was never finished,” says Faith Hubley, “but it enabled a number of us to grow up and become strong, mature people who made all those good movies. If John had had a career doing Hollywood features, he would never have become an independent.”

Rights to the animated Finian’s and the shards of the aborted production went to a New York company, Transfilm Productions. Ironically, David Hilberman, whose name Walt Disney had put before HUAC in 1947, was hired by Transfilm, as he recently explained in a letter, to “look into how much of the picture was completed and how much time it would take to finish it.” Hilberman had been directing films in “self-imposed exile in England” after his New York studio, Tempo, was blacklisted and closed in late 1953. Consequently, he says he “was not aware of what happened in the industry…. I don’t recall any discussion about who [would work on the project] and where the project would be completed. I see now I should have checked with John Hubley, but I guess I thought that might be awkward— I am very disturbed that the Hubley production was stopped by HUAC/Brewer/black-list. Had I known, I wouldn’t have touched the assignment with a 10-foot pole!” In any case, Transfilm did not pursue the project further.

Some years after the Finian’s Rainbow debacle, entrepreneur Michael Shore approached Fred Schwartz about an animated production of Don Quixote to be storyboarded by none other than Picasso. But that’s another story.

Acknowledgment: Besides the individuals mentioned in his article, the author would like to thank the following for their help and cooperation: Michael Sporn, David Hilberman, Ernie Har-burg.Jean Gordon, Jim Logan, Nick Markovich, Brian Mainolfi, Camille Dee, Mayann Chach, Adrienne Tytla, and Amanda Deitsch (Sotheby’s, New York).

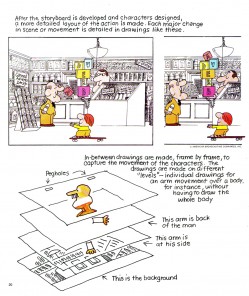

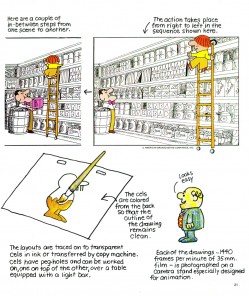

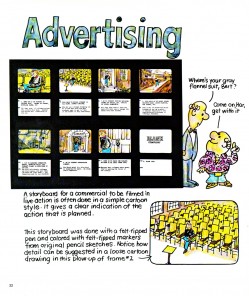

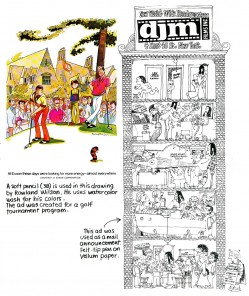

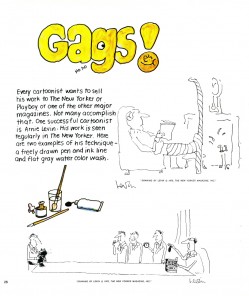

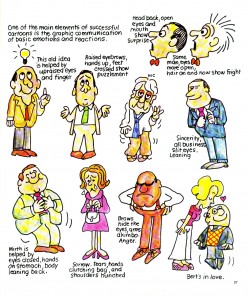

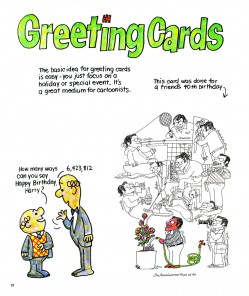

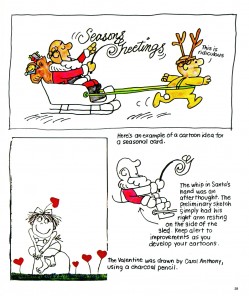

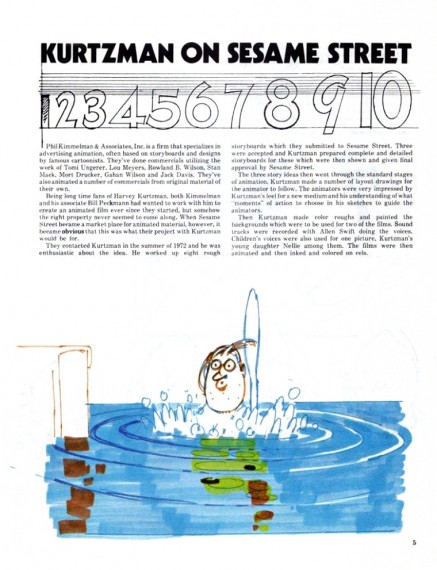

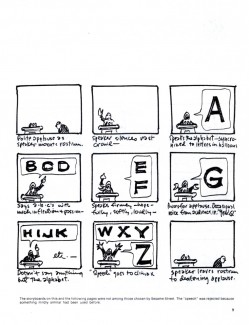

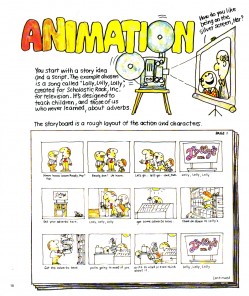

- It seems like ages ago that I posted the first half of this book. It was written by art director/designer, Jack Sidebotham who had a large presence in the making of the original Piels Bros. campaign done by UPA NY. He also was closely involved with the Scholastic Rock films.

- It seems like ages ago that I posted the first half of this book. It was written by art director/designer, Jack Sidebotham who had a large presence in the making of the original Piels Bros. campaign done by UPA NY. He also was closely involved with the Scholastic Rock films. 18

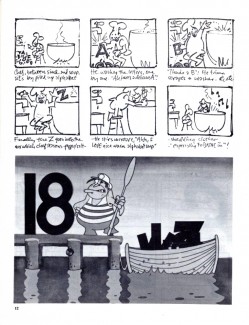

18 19

19