Here’s another survey of the year in animation for the March/April issue of Print Magazine circa 1976. Leonard Maltin did the surveying. Interesting that you don’t see many of this type article anymore.

An Animation

Overview

by Leonard Maltin

British animator Bob Godfrey has said, “Animation is a medium that deserves masters worthy of it. I’d like to see animation Picassos or Matisses, and we haven’t had any so far.”

Of course, Matisse never had to raise two million dollars in order to create one of his paintings, and Picasso didn’t have to oversee a staff of inkers and painters to make sure his newest canvas would turn out right.

The artist who chooses animation as his medium must endure certain realities: that films cost money, that extensive filmmaking becomes expensive filmmaking, and that except for the most monastic souls filmmaking is a collaborative process. This is not to eliminate the possibility of individual artistic expression in animation, but there are simpler ways known to man.

Once the artist has made his film, another set of realities comes to the fore: trying to find a distributor, or at least an audience, and with any luck, establishing a way of recouping the monetary investment of making the film. Since individual backing is hard to come by, to examine “the state of the art” of animation is to examine “the state of the industry” at the same time; it’s nearly impossible to separate the two.

In this country—as around the world— animation means so many different things that even the most cursory observations can expand to extreme lengths. “Animation” covers a lot of ground, from high-school kids filming paper cutouts with a Super 8mm camera to major Hollywood factories turning out Saturday morning drivel by the carload, but there are some significant outposts along the way.

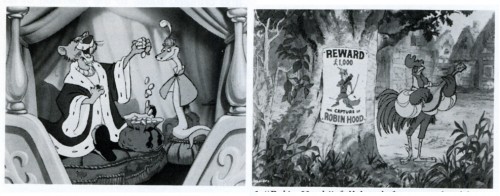

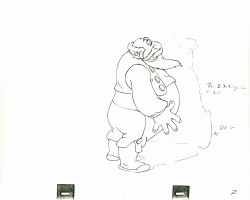

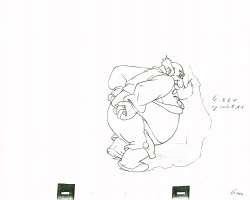

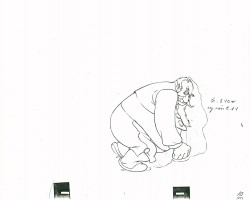

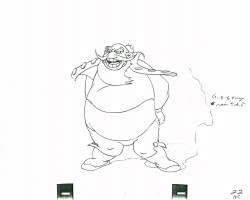

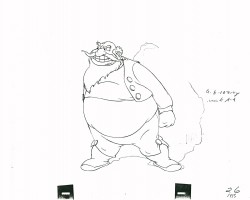

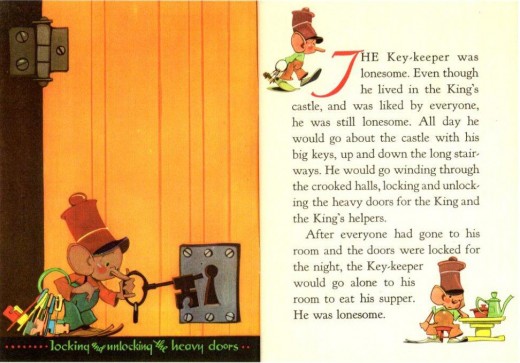

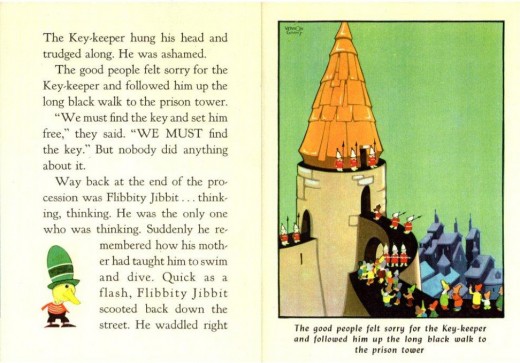

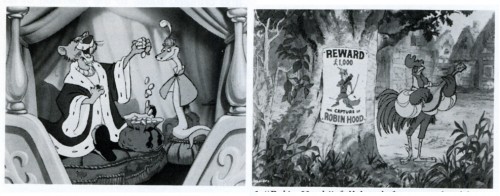

“Robin Hood” full length feature produced by Walt Disney Prods.

Producer/Director Wolfgang Reitherman.

Rumors of the Walt Disney Studio’s abandonment of cartoons are greatly premature. There was a time several years ago when the future of animation at the studio was in doubt, but the whopping worldwide success of the animated Robin Hood is just one reason that animated features are an ongoing project in Burbank.

The studio’s current endeavor is The Rescuers, which concerns two detective mice who head a society of do-gooders. Like other recent Disney features, it will comprise some four years of work— anywhere from three to four times as much as most competitors spend on similar projects. Rescuers is being aimed for Christmas of 1977, but there’s no guarantee that it will be completed on time. No one rushes this group of craftsmen.

The two main objectives in any Disney feature are a strong story line, the backbone of the film, and equally strong personality development, which gives the film its heart. Unfortunately, the approaches to these objectives have become increasingly routine in the 1960s and 70s at Disney, with much of the personality emanating from big-name stars doing character voices, and not so much from the animator’s pencil, although character animation is still superbly handled.

Practically everyone working on The Rescuers in a major capacity has been at the studio for 30 to 40 years, and Frank Thomas, a senior member of the team, admitted to John Canemaker, “We are less experimental. [With Walt] every picture was completely different. We were always pushed into things that were exceedingly difficult to do. He was always asking us to rise above ourselves. Well, when he left it up to us, we quit that. We got old. We decided we were going to do the things that were fun to do.”

The quality is still there, and the years of care and precision that go into a Disney feature show up on the screen. But somehow, the magic is missing, and that has nothing to do with time or money.

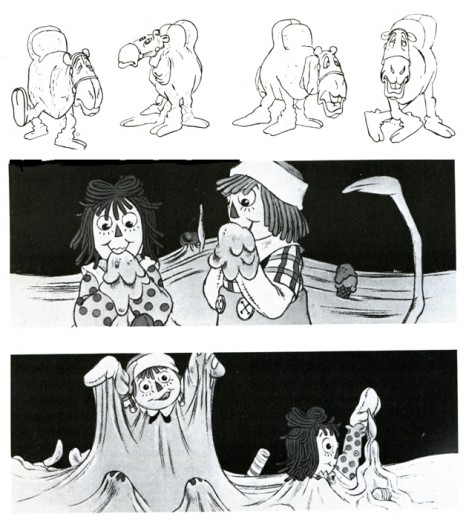

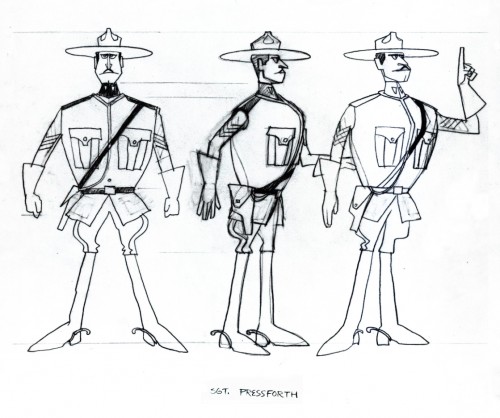

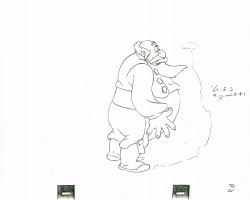

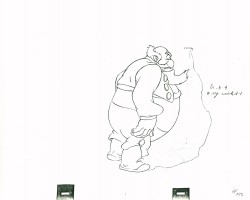

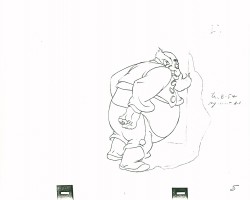

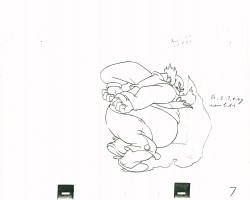

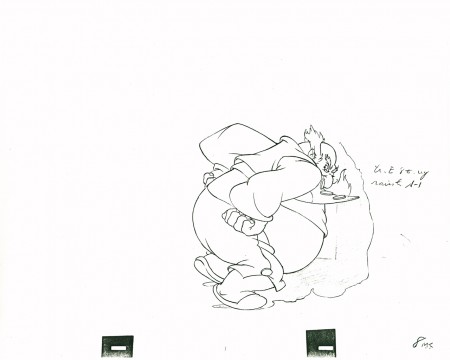

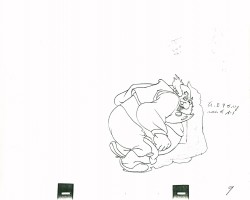

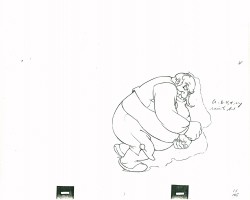

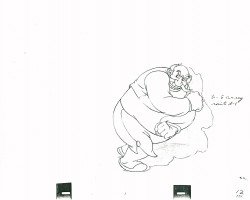

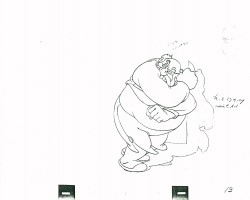

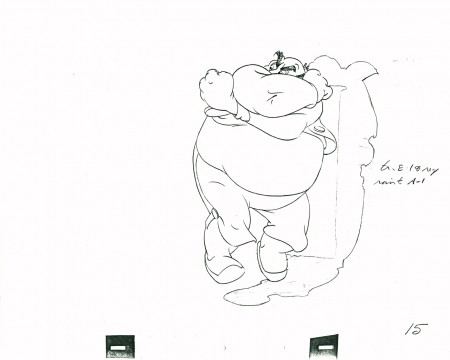

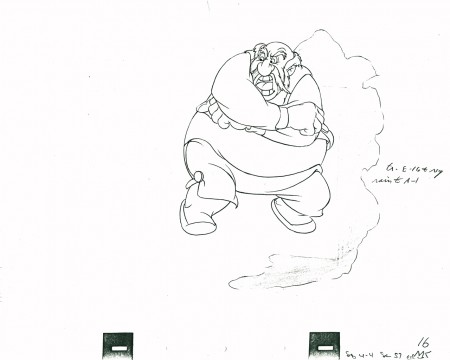

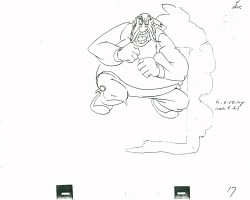

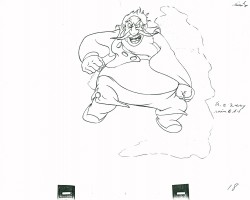

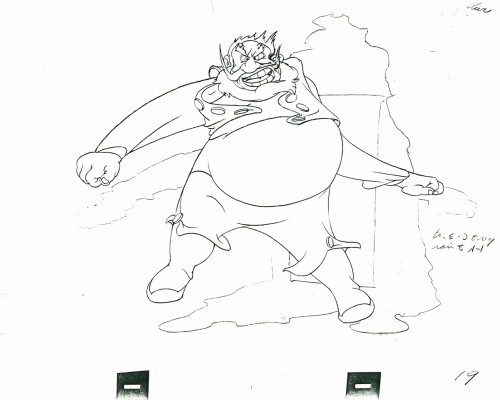

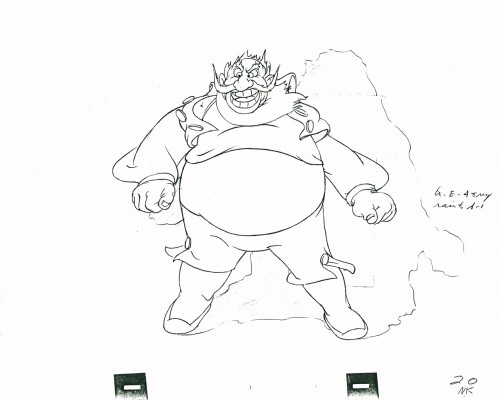

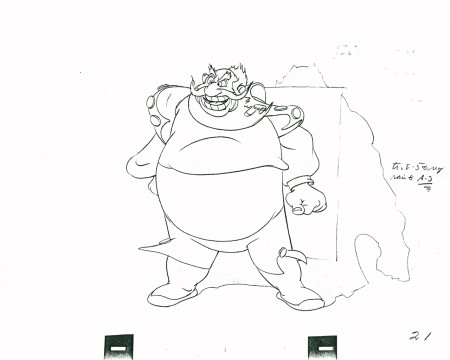

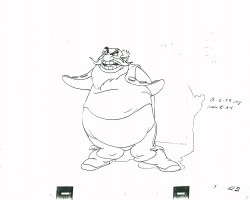

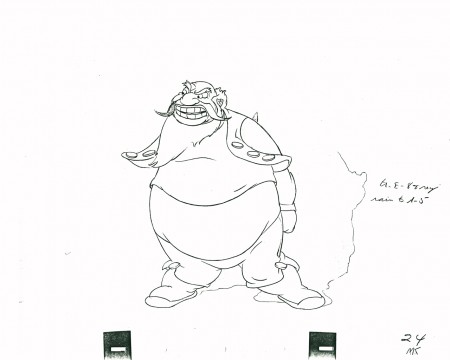

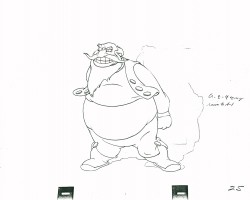

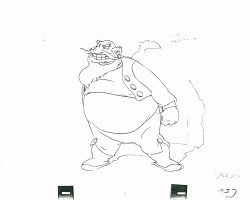

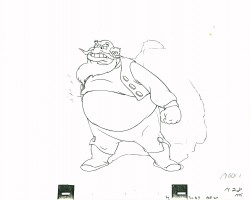

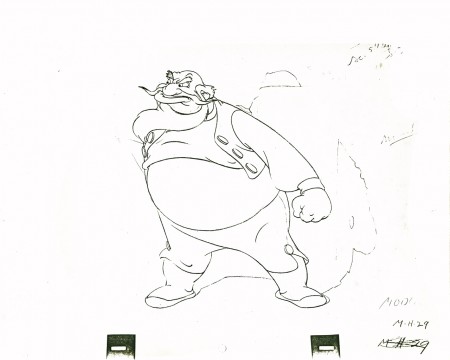

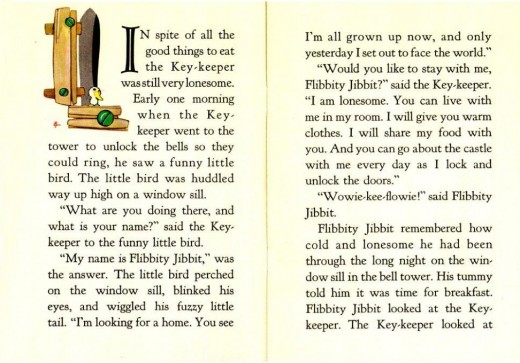

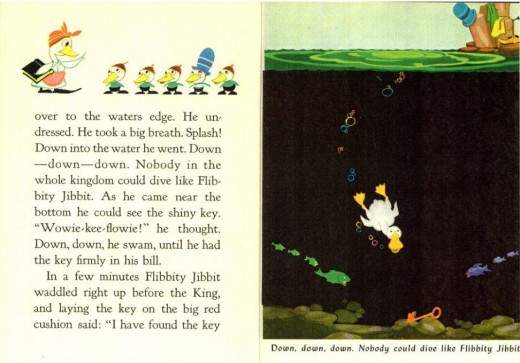

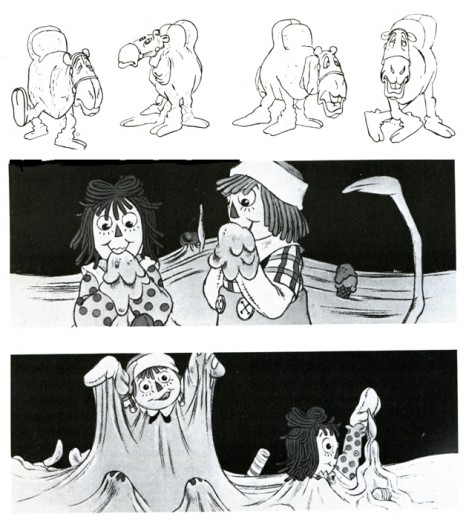

“Raggedy Ann & Andy” upcoming feqture based on Johnny Gruelle’s characters.

Production company: Lester Osterman Prods. Supervisor/director: Richard Williams.

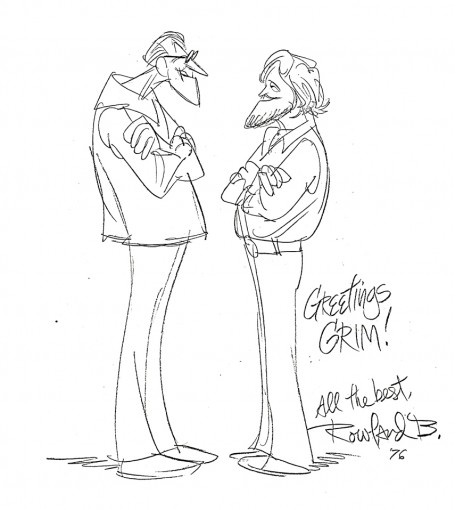

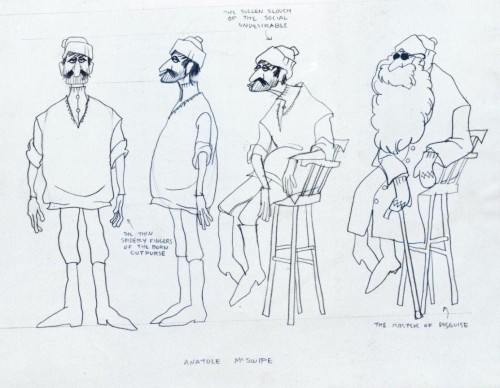

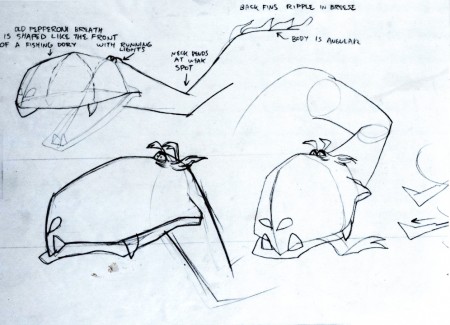

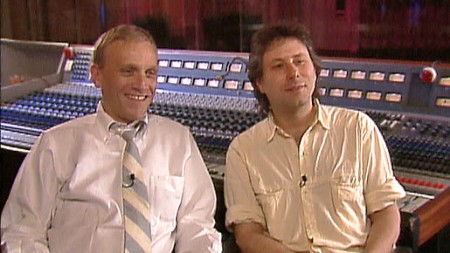

Into the breach steps a young man who has been hailed as “the new Disney,” Richard Williams. Canadian-born, British-based, he has impressed the animation world with his main titles for feature films (Charge of the Light Brigade, Return of the Pink Panther), theatrical shorts (“Love Me, Love Me, Love Me”), television specials (A Christmas Carol), and commercials.

The comparison with Disney is apt, because Williams has devoted himself tirelessly to the improvement of his work. Several years ago he began recruiting veteran Hollywood animators to come to London and work with his staff, as artists-in-residence, teachers, and colleagues. These men, in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, have all contributed to Williams’ pet project, an animated feature entitled The Cobbler and the Thief, which has been in progress for the better part of a decade. Williams and his people work on this when there is time, between commercial assignments. Among the distinguished Disney, Fleischer, and

Warner veterans who have pitched in are Art Babbitt, Shamus Culhane, Grim Nat-wick, and Ken Harris. It’s a two-way love affair, a happy collaboration between men of age and experience and younger animators with fresh ideas and outlooks.

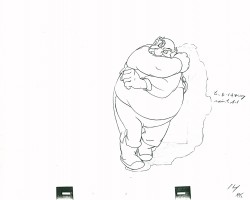

Now Williams is hard at work on an ambitious American project, a musical feature version of Raggedy Ann and Andy set for release at Christmastime this year. He has gathered a hand-picked staff in New York and supplemented it with freelancers from places as far off as Arizona.

Oher animated features are also on the way. It took Fritz the Cat to convince distributors and theater-owners that animated films shouldn’t be regarded as kiddie-show fodder and nothing more. Now John Hubley is directing a cartoon version of the bestseller Watership Down, while Fritz’s director, Ralph Bakshi, is working on his fourth feature film (the third, Hey, Good Lookin’, is about to be released). Producer Lee Men-dohlson and director Bill Melendez are working on a third Peanuts feature in California, while a New York operation has completed a feature-length remake of Tubby the Tuba. Other features are in production and planned for the near future.

But feature films tell only part of the story. Many filmmakers, amateur and professional, work in the realm of short subjects, and bringing these to the attention of an audience, not to mention a distributor, can be a long and wearisome process. One splendid showcase is the annual awards competition sponsored by the New York branch of ASIFA, the international animation society. Their recent screenings of this year’s winners revealed much about trends, goals, and styles in current films.

In the Student Film Category were three astoundingly professional products: Eduardo Damino’s “Hello,” a slick, imaginative treatise on the history and impact of telephones, using colorful cutout animation and an abstract soundtrack; Stephen Ciodo’s “Cricket,” a finely crafted stop-motion film for children about a cricket who is ostracized by his peers because he’s unable to jump; and Linda Heller’s “Album,” a most intriguing series of vignettes based on flashbacks and flash-forwards in a photo album of a woman’s life.

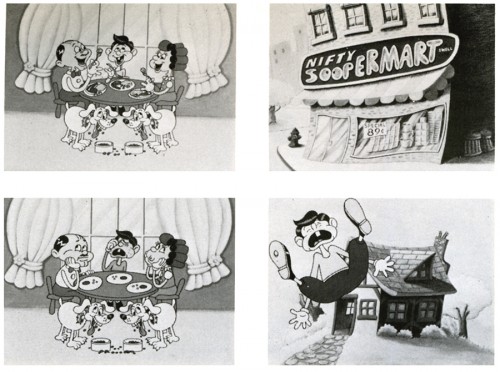

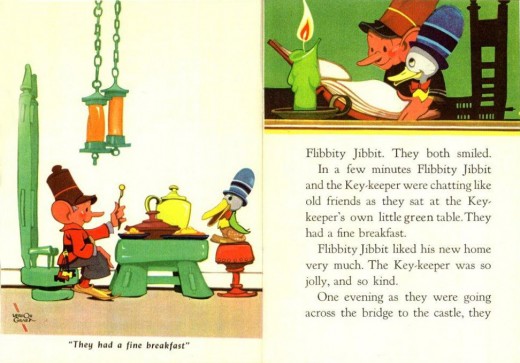

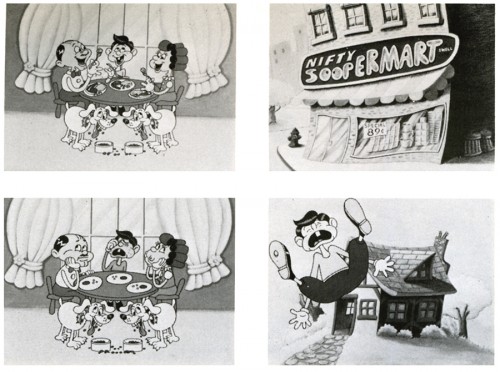

“A Dog’s Life” Due to soaring food prices, a family eats less while their dogs eat more.

Production company: Perpetual Motion Pictures | Producer: Marshall Patinkin

Director/designer: Hal Silvermintz | Animator: Vince Cafarelli

.

A vital category for prizes at ASIFA East is the Non-Sponsored Professional Film. Chapter president Dick Rauh explains that this category is intended to encourage members to take the time to make personal films, apart from their daily assignments; indeed, the five winners showed a wide range of highly individual styles and goals.

Mary Beams’ “Going Home Sketchbook” has an interesting visual concept, combining sketches, line animation, and what seems to be a rotoscope technique to create an impressionistic view of a trip home; unfortunately, there is no development within the film to give it any real interest beyond that technique. “Deep Sleep” is a feminist-oriented film by Peggy Tonkonogy that details a woman’s long, weird symbolic dream; again, an aimless-ness is somewhat compensated for by excellent visual effects. Both of these films received Honorable Mention.

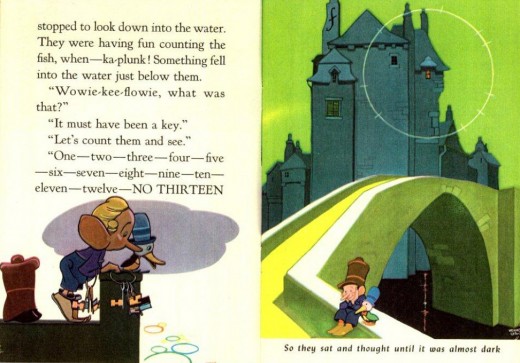

George Griffin’s “L’Age Door” is an irresistible film that perfectly meshes form and content as a man is confounded and swallowed up by an endless succession of doors. Short, sweet, and quite funny. Griffin’s film won Third Prize in this category.

“Quasi at the Quackadero,” Second Prize-winner, is one of the most bizarre animated films I’ve ever seen. Sally Cruickshank’s visual extravaganza bears repeated viewings, just to absorb everything that’s happening on-screen; the style might be described as freaked-out George Herriman. Significantly, Cruickshank labels her film “a cartoon,” showing strikingly-designed characters attending a futuristic amusement park where the games and rides are based on time- and life-warps.

First Prize was awarded to Kathy Rose for her quiet and enjoyable film “The Doodlers,” the basic premise of which is that drawings beget drawings.

In the general categories, awards were divided according to soundtrack, technique, script/concept, humor, design, animation, and direction. Most of these were commercial and/or sponsored films, including several delightful commercials from Phil Kimmelman and Associates, a funny NBC “Weekend” gag-film by Ovation Films, some dazzling 7-Up graphic spots by Goldsholl Associates, and two fine shorts by the Wantu Studio headed by the talented James Simon.

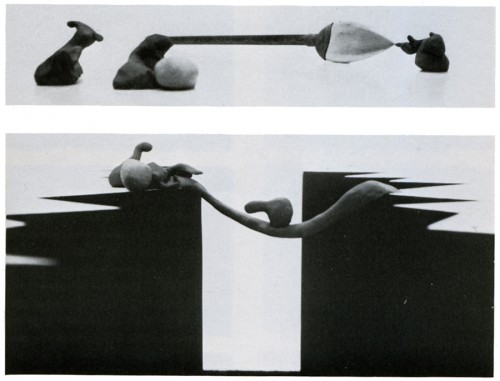

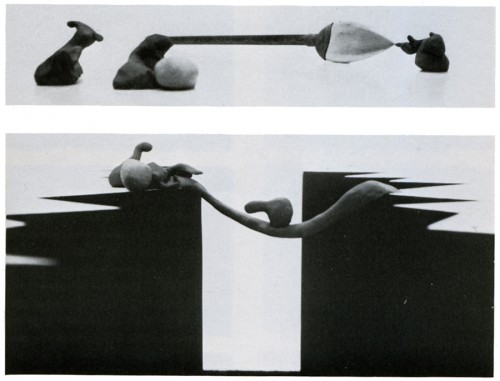

“Whazzat” Clay figure animation based on blind man and the elephant

Sponsor: Encyclopedia Britannica |Production company: Crocus Pictures

Producer: Tel C. Determan | Director: Art Pierson.

Awards for Best Animation and Best Direction went to Arthur Pierson and his associates Ron Lasner and Alan Baker for a disarming stop-motion clay film called “Whazzat?” (which had already won Spe-cialJury Prize for Best Film at the New York Animation Festival). The premise of “Whazzat?” has six clay objects assuming vivid personalities, although they have no faces or identifying features; together, they travel and enjoy each other’s companionship, until they come upon a strange being unknown to them. Through sophisticated and knowing animation, camera placement, and ingenious use of soundtrack, “Whazzat?” makes something special out of something elegantly simple.

Best Film in ASIFA’s competition was another repeater from the New York Festival, Stan Phillips’ “Water Follies,” produced as a soft-sell promotional film for the Denver Water Commission. An entertaining series of blackout gags on uses and abuses of water, this straightforward film quietly goes about its business and scores a bull’s-eye with its entertaining point of view and uncluttered animation style.

One may be hesitant to accept the idea of slick, professionally sponsored films competing with more personal, individual works. But the ASIFA screening brings out something very important about animated films. They come from individuals and they come from large companies; they range from utter simplicity to overstuffed detail, from quietude to clutter. But each film stands on its own, with its own set of goals to be met, and if it fails, all other considerations become worthless.

Not every professional film is better than an amateur effort. There are films made by eight- or nine-year-olds which burst with imagination and daring visual ideas; they put some professional filmmakers to shame. Likewise, some one-minute TV commercials are so outstanding in every respect (animation, design, humor) that they overpower more “serious” artistic works shown alongside them.

But does the film succed on its own terms? Be it Disney, Bakshi, commercial or collegiate, that’s the only question that really counts.

1

1  2

2  3

3

1.”Teeth Care” Sesame Street – Prod/Dir: James Simon Animator: Jack Schnerk

2. “The Strike” Morris Funk Foundation Prod/Dir: James Simon

Animators: Cosmo Anzilotti, Lu Guarnier, Ed Smith, Sal Faillace

3. “I Want My Avis” Prod Co: PK&A | Prod: Hal Hoffer

Designer: Mordi Gersteion | Animator: Jack Dazzo

4

4  5

5  6

6

4. “Water Follies” Sponsor: Denver Water Dept | Prod/Designer: Stan Phillips

5. “Ou Hound” CTW | Prod/Dir/Anim: John Strawbridge

6. “French T-Shirts” Bloomingdales | John Gati Film Effects

7

7  8

8

7. “Carton Graphics” 7-up | Goldscholl Associates

Designer: Morton Goldscholl Dick Greenberg

8. “No More Puckers” Yoplait Yogurt | PK&A producer: Sid Horn

Director: Phil Kimmelman | Designer: Bill Peckmann | Animator: Lu Guarnier

Leonard Maltin teaches the history of animation at the New School for Social Research, New York City, and is author of The Disney Films, among other movie books. He is currently guest programmer for the Museum of Modem Art’s “Salute to Film Comedy.”

1

1

Left

Left 1

1

2

2

4

4

6

6

8

8

10

10

– Back in 1973, the Hubleys produced

– Back in 1973, the Hubleys produced