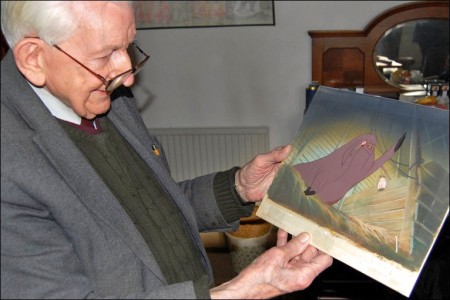

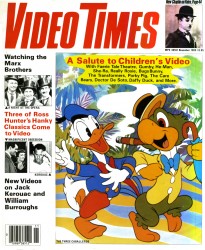

- The following interview with Mel Blanc appeared in the Nov, 1985 issue of Video Times Magazine. By this time, Mel Blanc was on automatic pilot. He’d answered these same questions hundreds of times, so there may not be much original information here. I think it’s informative and entertaining just the same.

- The following interview with Mel Blanc appeared in the Nov, 1985 issue of Video Times Magazine. By this time, Mel Blanc was on automatic pilot. He’d answered these same questions hundreds of times, so there may not be much original information here. I think it’s informative and entertaining just the same.

The Man of

A Thousand Voices

Mel Blank Croons a Looney Tune

Editor’s Note: We could think of no better way to end our special report on children’s video than to chat with the one man whose name has become synonymous with some of the most-beloved cartoon characters: Mel Blanc, better known as the voice of Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, and many other zany cartoon characters. Gregory Cat-sos recently caught up with this 77-year-old Tasmanian devil (who is still working a full schedule) for a short conversation.

VIDEO TIMES.- Who is your favorite cartoon character?

Mel Blanc: Bugs Bunny. Bugs is the closest to me. He’s my favorite character because, without him, I don’t know what might have happened. He’s been more or less my main leading character. Not long ago, Warner Brothers conducted a poll among 10,000 children to determine what cartoon characters they liked best. Bugs Bunny came out number one. That made me realize how popular this “cwazy wittle wabbit” is. I hope it continues on that way.

Mel Blanc: Bugs Bunny. Bugs is the closest to me. He’s my favorite character because, without him, I don’t know what might have happened. He’s been more or less my main leading character. Not long ago, Warner Brothers conducted a poll among 10,000 children to determine what cartoon characters they liked best. Bugs Bunny came out number one. That made me realize how popular this “cwazy wittle wabbit” is. I hope it continues on that way.

VT: What character that you do is your real voice closest to?

MB: I’d say Sylvester, the cat, is the closest to my straight voice. I almost sound like him in real life.

VT: Each cartoon character you ‘ve created is different from the other.

MB: I always tried to make each character different or unusual. These characters have their own peculiarities, their own unique personalities. Like Daffy Duck’s crazy laugh, Bugs Bunny’s style of talking, Porky Pig’s stuttering, and the “spraying” sound of Sylvester when he talks.

VT: Warners has released a series of classic cartoons on videotape: Bugs Bunny’s Wacky Adventures, Daffy Duck: The Nuttiness Continues, A Salute to Mel Blanc, and others. How do you feel about this?

MB: I’m happy about it. People with video machines can now collect some of their favorite cartoons. The Salute to Mel Blanc tape contains some of my personal favorites: “The Rabbit of Seville” (1950), “Robin Hood Daffy” (1958),

“Ballot Box Bunny” (1951), and “Bad O1* Putty Tat” (1949).

VT: How many cartoon voices have you provided these past 50 years?

MB: For Warner Brothers alone I did about 700 different voices. I can also do 400 more different voices and dialects. So when they call me, The Man of 1000 Voices, they’re not kidding.

VT: Besides Warner’s cartoons, who else have you worked for?

MB: I’ve done the voices of Barney Rubble and Dino the Dinosaur in The Flintstones. I’m doing voices again for The Jetsons, with Penny Singleton. I also provided the original voice of Woody Woodpecker in 1936. Walter Lantz had asked me to create a voice for his woodpecker character. 1 did a few cartoons for his studio. But I had to stop doing Woody’s voice when I signed an exclusive contract with Warner Brothers. After that, a woman named Grace Stafford did the voice. I guess Walter Lantz didn’t want to lose her, so he wound up marrying her (laugh).

VT: Are there any voices that you Haven’t provided in the Warners’ cartoons?

MB: I did practically everybody except Granny (in the Sylvester and Tweety Pie cartoons). And in the beginning, I didn’t do Elmer Fudd. His voice was done for many years by Arthur Q. Bryan. After Bryan died in 1958, I began doing Elmer. But I didn’t want to imitate Bryan’s voice. 1 did my own interpretation of Elmer’s voice. I don’t like to imitate. I’m a creator of voices, not an impersonator.

.

.

VT: When did you start doing cartoon voices?

MB: In 1936. I did a drunken bull character in a cartoon called “Picador Porky.” Initially, I had some difficulty getting into the cartoon business. I tried many times to get an audition at Warner Brothers, but I was always told, “Sorry, but we have all the voices we need.” I kept going back for over a year and a half, but the man in charge still said, “No.” Finally, this man died. So I went over to Treg Brown, who was the head of the sound-effects department of animation, and asked for a job.

Treg listened to my audition and liked it. He even had me audition for some directors and producers at the studio. One director, Tex Avery, said to me, “Can you do a drunken bull?” I said, “I think so.” And Tex asked, “What would he sound like to you?” So 1 did my impression of what I considered to be a loaded bull, hiccuping and slurring my speech. He said, “That’s perfect! What are you doing next Tuesday?” Well, I wasn’t doing a damn thing. But I said, nonchalantly, “Oh, I think I can make it” (laugh). That’s how it all started.

VT: Did you also do Porky Pig’s voice in “Picador Porky”?

MB: No, I didn’t do Porky Pig at the time. The studio had a man there named Joe Dougherty, who actually stuttered in real life, who was then doing Porky. But this guy had problems coming in on cue and doing the dialogue properly. So the studio asked me if 1 could stutter on cue, to do Porky’s dialogue with the right timing, I did my interpretation of Porky’s voice for them, and they liked it.

VT: What was the first cartoon in which you did the voice of Porky Pig?

MB: 1 think I did Porky’s voice for the first time in “Porky’s Romance” in 1937.

VT: Did you have scripts for the cartoons?

VT: Did you have scripts for the cartoons?

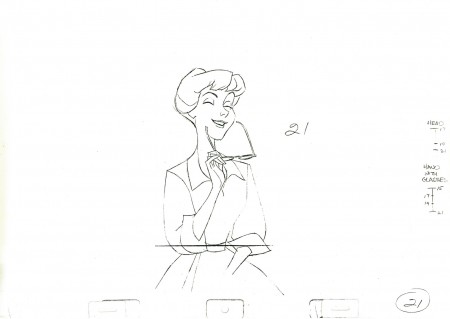

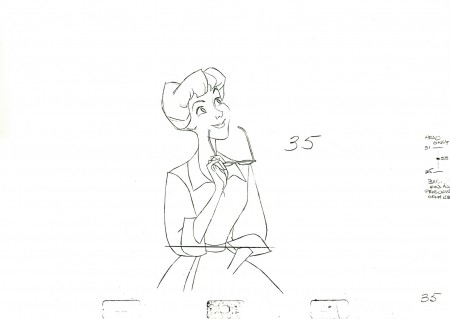

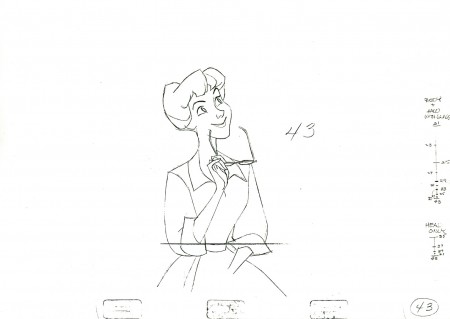

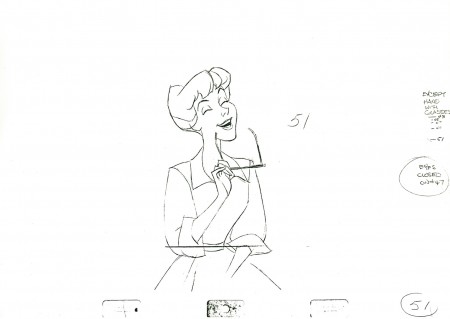

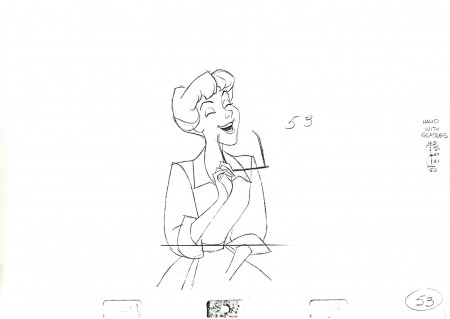

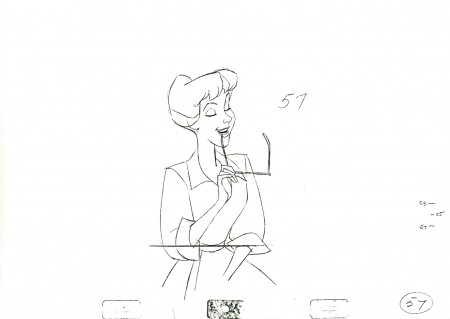

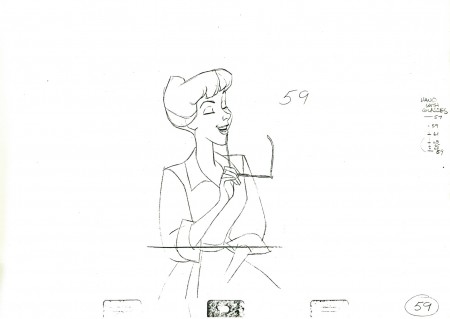

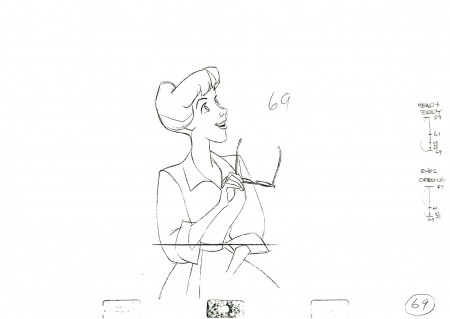

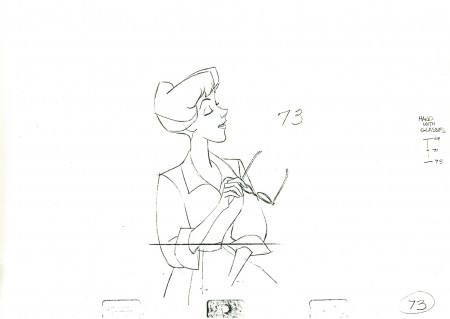

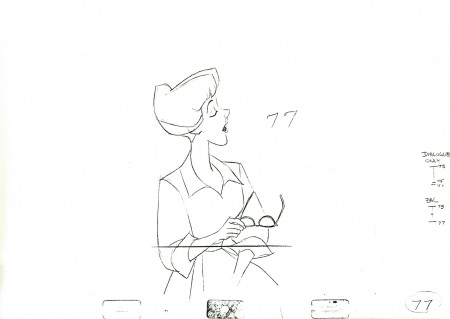

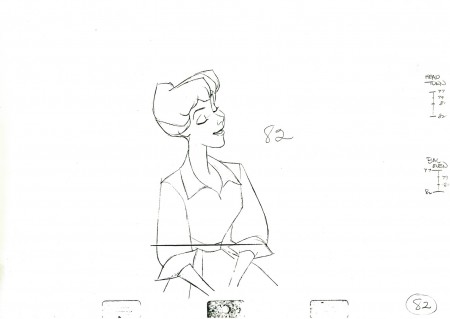

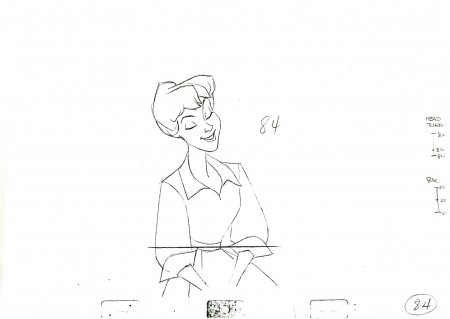

MB: Absolutely, but first the writers showed me the storyboard. Through a series of pictures, the storyboard showed what the cartoon was about and what the characters would say and do. Then I created the voices.

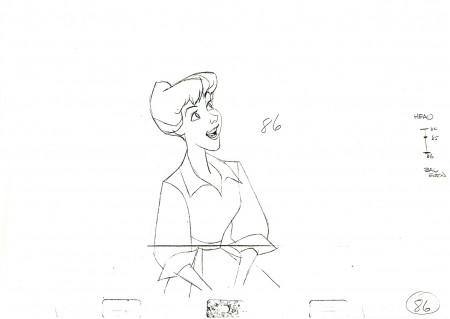

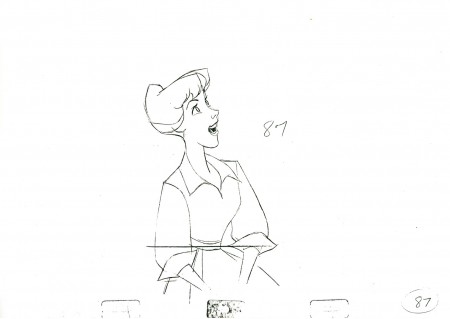

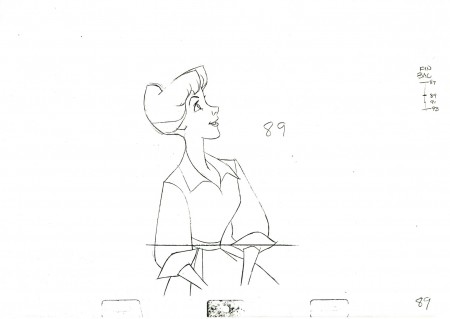

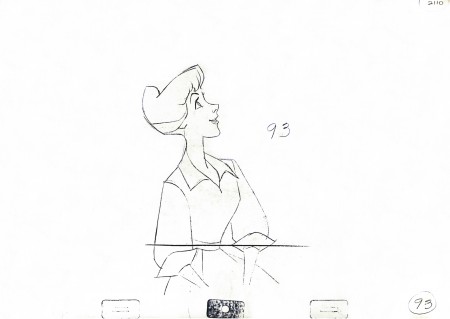

VT: How long did it take the animators to make one cartoon?

MB: It would take 125 people about 9 months to make one 6-1/2 minute cartoon. Of course, they all worked on more than one cartoon at a time. These animators were all specialists. One would draw Bugs Bunny; another would create Daffy Duck; another would do the backgrounds, and so on.

VT: How long did it usually take you to do the voices for one cartoon?

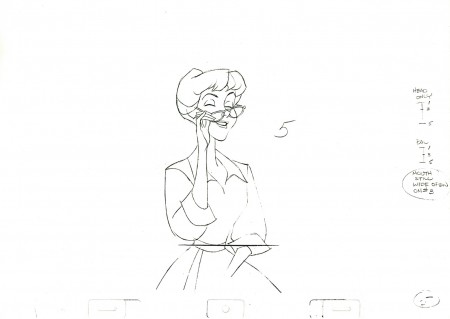

MB: About an hour per voice. Originally it would take me about a day and a half to do all the voices. The voice is done first, you know. From the voice the animator draws pictures to fit the mouth movements. The animator looks in the mirror and copies his own mouth movements on the character and captures the right facial expressions. My dialogue is also timed with the footage.

Eventually, I suggested to the directors, “Why don’t you record each character individually? Let me do each voice first!” This way, I didn’t have to jump back and forth anymore. So they recorded each character’s lines individually. It saved a lot of time and money for the studio, and it was a lot easier for me this way.

VT: How much freedom did you have in contributing to the characters or the dialogue?

MB: I was given a lot of freedom with the cartoon characters, especially in contributing to their dialogue. I sat in on the story conferences and gave the writers and directors some of my own ideas. In many of the cartoons, I more or less ad-libbed a lot. My ad-lib was timed to the exact second. If I didn’t feel that certain dialogue was appropriate for Bugs Bunny, I ad-libbed something better or more in character for him, or I suggested substituting another line. And 99 times out of 100, the director agreed that my ad-lib or change in dialogue was better than what was in the script. For example, they were originally going to have Bugs say, “Hey, what’s cooking?” in all the cartoons. I said, “Instead of that corny expression, can’t we use a funny expression that’s been going around, What’s up, Doc?” The writers agreed that sounded better, and we used that catchphrase instead. I also ad-libbed something in “Knighty Knight Bugs” (1958). King Arthur sent out Bugs Bunny, the court jester, to take away a singing sword from the Black Knight (Yosemite Sam). After recapturing the sword, Bugs was supposed to say, “So this is the singing sword? How do you like that?” But instead, I said, “So this is the singing sword? Big deal!” 1 ad-libbed, “big deal!” It sounded better than the original line, and Friz Freleng, the director, kept it in.

VT: When Bugs Bunny chews on a carrot and says, “What’s up, Doc?” are you really chewing on a carrot?

VT: When Bugs Bunny chews on a carrot and says, “What’s up, Doc?” are you really chewing on a carrot?

MB: Yes, I actually chewed on a carrot. We had originally tried potatoes and celery but discovered the only-things that made the sound of a carrot was me chewing on a real one. But when 1 got a mouthful of carrot, I couldn’t swallow it all in time and then talk like Bugs. So, we’d stop recording for a moment, and I’d spit the carrot out in the wastebasket. Then, I would go on with the rest of the dialogue. I used to fill a few waste-baskets a day in order to do a little dialogue.

VT: Why does Bugs Bunny kiss Elmer Fudd on the lips in many cartoons? What’s that all about?

MB: The writers had put it in to get some more laughs in the cartoon. They thought this would be funny. At the time, we didn’t think anything of it. It was just an unexpected thing for Bugs to do. Elmer Fudd is pointing his shotgun at Bugs. Instead of being afraid, Bugs grabs Elmer and kisses him! Now, a rabbit kissing a man, in itself, was ridiculous. It got a good laugh and they kept using the gag. Warners had some marvelous and inventive writers in those days. They experimented with a lot of gags for Bugs that would look absurd. This was one of them, When I talk at colleges, some students will ask, “How come you never know what Bugs is? He keeps kissing Elmer and the other guys.” And 1 answer, “Bugs is not gay.” It’s just a gag that worked, and the writers used successful gags over and over. VT: What other gags were used a lot? MB: They had several running gags. Like the funny little signs Bugs or Daffy held up saying, “Funny isn’t he?” In one Road Runner cartoon, “Gee Whiz-z” (1956), the coyote falls off a cliff and holds up a sign saying, “How about ending the cartoon before I hit?” Another gag is, Bugs opens a door and finds another door behind it, followed by another door, and so on. Or Elmer Fudd points his shotgun at Bugs. Then, Bugs bends the barrel of the shotgun back the other way, so now it’s pointing at Elmer instead.

VT: When was Daffy Duck introduced?

MB: Daffy Duck was introduced in “Porky’s Duck Hunt” (1937). The cartoon was very funny and ended with Daffy hopping up and down, laughing over the “That’s all, folks” title card.

VT: When were Tweety and Sylvester introduced?

MB: In two separate cartoons. Tweety, the canary bird, was introduced in “Birdy and the Beast” (1944). Sylvester, the cat, made his debut in “Life with Feathers” (1945).

VT: How did they come up with Tweety Bird’s expression, “I taw a puttytat”?

MB: I said that phrase at one of the meetings—one of our story conferences. The writers thought it was a catchy line, and we used it in the Tweety cartoons. The same thing happened for Sylvester’s expression “suffering succotash.” We developed all these kinds of lines at our meetings.

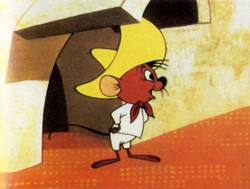

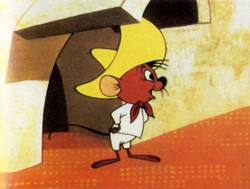

VT: How about Pepe le Pew, foghorn Leghorn, Yosemite Sam, and Speedy Gonzalez? When were they introduced? MB: Pepe le Pew made his first appear-ance in “Odor-able Kitty” in 1945, Foghorn Leghorn in “Walky Talky Hawky” in 1946, and Yosemite Sam in “Hare Trigger” in 1945. Speedy Gonzalez’s first cartoon was “Cat Tails for Two” (1953). That shows you how long these characters have been around.

VT: How about Pepe le Pew, foghorn Leghorn, Yosemite Sam, and Speedy Gonzalez? When were they introduced? MB: Pepe le Pew made his first appear-ance in “Odor-able Kitty” in 1945, Foghorn Leghorn in “Walky Talky Hawky” in 1946, and Yosemite Sam in “Hare Trigger” in 1945. Speedy Gonzalez’s first cartoon was “Cat Tails for Two” (1953). That shows you how long these characters have been around.

VT: How about the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote?

MB: The Road Runner and the Coyote made their first appearance in “Fast and Furry-ous” (1949). This was the first time the Coyote chased the Road Runner in the desert. Chuck Jones was responsible for creating this series. I didn’t do the voice in the first Road Runner cartoon. The studio used a Klaxon horn to make the beep sound. I started doing the cartoons after the first one was made. One day, the studio couldn’t find their Klaxon and asked me to do the sound.

VT: What kind of director is Chuck Jones?

MB: Chuck Jones is a great director. When Chuck directed me he told me exactly what he wanted to convey in the cartoon. He’d also do some of the dialogue beforehand to demonstrate what he wanted me to do with the lines, the voice inflection, and the pauses between the lines. All of Chuck’s cartoons are well structured. In his Bugs Bunny cartoons, Chuck usually showed a reason for Bug’s mischievous behavior. Bugs Bunny is usually minding his own business in the rabbit hole. Then Elmer Fudd or somebody else comes along and bothers him. So Bugs says, “Of course, you know this means war!” and fights back. VT: What, in your opinion, are Chuck Jones’ funniest cartoons? MB: I think many of his Road Runner cartoons are very funny, such as “Zoom and Bored” (1957) and “Hook, Line, and Stinker” (1958). Warner Brothers has released a videotape titled, A Salute to Chuck Jones. On it are some of his greatest cartoons: “Duck Dodgers in the 24′/2 Century” (1953), “For Scentiment-al Reasons” (1949), and “What’s Opera, Doc?” (1957).

VT: Musical backgrounds are prominent in Warners cartoons, aren’t they?

MB: Yes, music was an important ingredient. Carl Stalling—and later on, Milt Franklyn—musical directors, used many popular melodies to advance the plot of the cartoons. They tried to make the melodies fit the situations. For example, if there was a lady in a red dress, their orchestra played “The Lady in Red.” If a character was leaving on a trip, you’d hear “California, Here I Come.” Something about Hollywood or movie stars would be “You Oughta Be in Pictures” or “Hooray for Hollywood,” and so on.

VT: Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck do a lot of singing in the cartoons. Why?

MB: The studio knew I could sing pretty well and that I was also a musician. So the directors asked me to do some singing in the different voices I did. In Bugs and Daffy’s voices I sang bits and pieces of songs like “Someone’s Rocking My Dreamboat” or “Singing in the Bathtub.” In the “Rabbit of Seville” (1950), 1 had Bugs sing “Figaro.” In fact, Carl Stalling even wrote a special song for Bugs to sing called “I’m Glad I’m Bugs Bunny.”

VT: Do you get residuals when your cartoons are shown on TV?

MB: Yes, I do. It’s in my contract with Warner Brothers.

VT: For most of your career not many people knew it was Mel Blanc doing ait those cartoon voices. Did that bother you?

VT: For most of your career not many people knew it was Mel Blanc doing ait those cartoon voices. Did that bother you?

MB: Yes, 1 kind of felt bad because the cartoon characters themselves had become so popular. When I finally did the American Express commercial a few years ago, people became aware of who I was. But I used to go to restaurants and nobody recognized me. Now, 1 can’t walk down the street or into a restaurant without somebody asking me, “Hey, have you got your American Express card with you?” And I answer, “Yes, I don’t leave home without it!”

VT: What’s next for Mel Blanc?

MB: All I can say is, “That’s not all folks!”

— GREGORY J. M. CATSOS

1

1  2

2

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 18

18 19

19 20

20 21

21 22

22 23

23 24

24 25

25