Here’s an interview with another International Independent master of animation. Again, many of you may not have heard of him, but let me assure you that his work bordered on genius. His film, Pojar, kept me inspired for years after I saw it in Annecy in 1976. Just check out the body of work done prior to 1980; by 2007 he’d done about 60 short films. He was prolific and smart. If you can find his films, watch them.

This interview comes from Animafilm #5, March 1980.

To Start from Material

Marcin Gizycki talks with

Witold Giersz

MARCIN GIZYCKI: How many films have you made?

WITOLD GIERSZ: I have never compiled statistic, but they said once at the Studio of Film Miniatures that there were about forty.

M.G.: The fruit of the twenty odd years of your activity.

W.G.: I started to work with the film illustry as early as 1950, at the Cooperative of Animated Cartoons in Bielsko.

M.G.: You were among the pioneers of the animated film in Poland.

W.G.: That was long ago.

M.G.: You made your debut in 1956 when you did “The Mystery of the Old Castle”. But the turning point in your career was “The Neon Trifle” and “The Little Western”.

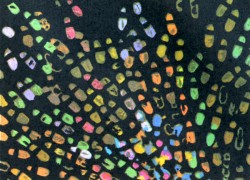

W.G.: Indeed. “The Neon Trifle” was my first, very timid, attempt to abandon conventional drawing, i.e. contours filled with colour. I did my drawings with a brush, which created the impression that the characters were made of neon tubes. In “The Little Western” I made use only of patches of colour which 1 put with a brush straight onto the celluloid.

M.G.: You were the first film-maker in Poland and, if I am not mistaken, in the world, to use this technique, namely, painting on the celluloid without a whole staff of assistants.

M.G.: You were the first film-maker in Poland and, if I am not mistaken, in the world, to use this technique, namely, painting on the celluloid without a whole staff of assistants.

W.G.: I tought so, too, but, to my surprise, when I showed “The Little Western” at the Festival in Annecy, George Dunning presented his “Flying Man”, made in a very similar way. We arrived at similar results independently and it does not really matter who was the first. Let’s be quite clear about it: both films used the traditional celluloid technique; the only innovatory thing was the form of drawings: contours were by patches of colour.

M.G.: It seems that you have tried all possible forms of animation, you gave even made a puppet film, “Expectation”. However, your name evokes associations primarily with “dynamic painting”, i.e. the gradual transformation, through the addition and erasure of painted elements, of a single picture done in a thick layer of wet paint. Do you agree that this is the most characteristic undercurrent in your art?

W.G.: People call it the most characteristic because, apart from Piotr Szpakowicz, no one uses this technique in Poland. Naturally, our methods are somewhat different. Szpakowicz deals, on the main, with static painted surfaces that evolve as a result of interpenetration. When he introduces animation, it is less complex than with me. But to be quite frank, I have used this method in three films only: “The Horse”, “The intellectualist” and “The Fire”. Nevertheless the story goes that this is my technique. Generally, I have worked quite traditionally. I am especially fond of animation on the celluloid if it is in “The Little Western”.

M.G.: What I particularly appreciate in your films such as “The Little Western” or “The Red and the Black” is the wit based on purely visual efffects. For instance, a clash of two figures, yellow and blue, which leads to the emergence of single huge green figure. This gag could only be born as a result of thinking in terms of pictures, and only in an animated film.

W.G.: This sort of ideas came to me when I was already working on the film and that is why they could not be the starting point for the script. I regret that they did not occur to me earlier, then I could have subordinated the entire plot to them. I think that the starting point should lie in the material. I tried to follow this path in “Expectation”. There, from the very beginning I kept thinking about a plot in which to involve the figures made of tissue paper made by Ludwik Perski. What drama, what tragedy can be designed for a tissue ballerina? Crumpling, tearing or, in the worst case, burning? What can her sensations be? Light, banal, for she is only a paper dancer. This gave rise to the whole plot.

M.G.: You have once said: “I made myself all my films that I find fairly satisfactory (…) all those made in collaboration have turned out mediocre. How do you explain it?

W.G.: Group work hinders one’s approach in the visual sphere. If Lenica had had to work with a group, he would have never made “New Janko the Musician” or the “Labyrinth”. If we work with a dozen, however talented designers, and we do not want to come up with a conglomerate of a dozen, however good, diverse works, we must restrain ourselves and fall into line. One’s own individuality must be given up in favour of a homogeneous final effect. One’s individual mark may be imprinted only in the way we develop the plot, on the dramatic quality, but visually, there is no room for shining out.

M.G.: And yet, you have made films in collaboration with others.

W.G.: Let me explain. In Bielsko. I went through a good traditional school of classical animated cartoons, cultivated there until today. I thought that I had become quite skilful at this technique and originally I planned no other methods. However, as time went by, I ceased to be satisfied, I came to the conclusion that all I knew about workmanship did not mean much, that what really counted in animation and was pleasing to the eye was novelty. After a good deal of research, I finally arrived at something that gave me some satisfaction. I mean the series of films from “The Little Western” to “The Fire”. But from time to time I go back to traditional cartoons, which I regard as my duty towards the company. Certain films are commissioned and I have to carry them into effect. However, I have not made a film with a group of animators for a very long time now. “Please, Elephant” is no exception, as this full-length film uses the material shot for a serial eleven years ago, with only junctions and some other little things done now. I did all the alternationas practically myself, assisted by one animator.

W.G.: Let me explain. In Bielsko. I went through a good traditional school of classical animated cartoons, cultivated there until today. I thought that I had become quite skilful at this technique and originally I planned no other methods. However, as time went by, I ceased to be satisfied, I came to the conclusion that all I knew about workmanship did not mean much, that what really counted in animation and was pleasing to the eye was novelty. After a good deal of research, I finally arrived at something that gave me some satisfaction. I mean the series of films from “The Little Western” to “The Fire”. But from time to time I go back to traditional cartoons, which I regard as my duty towards the company. Certain films are commissioned and I have to carry them into effect. However, I have not made a film with a group of animators for a very long time now. “Please, Elephant” is no exception, as this full-length film uses the material shot for a serial eleven years ago, with only junctions and some other little things done now. I did all the alternationas practically myself, assisted by one animator.

M.G.: Animated film lies on the borderline of two disciplines: the visual art and feature film. Do you agree that an animated film d’auteur has more of the former, whereas an animated film produced by a team is more like the latter?

W.G.: There are films that can obviously pass as works of the visual arts, like for instance, all Szpakowicz has done. Nevertheless, I think that animation has worked out means of expression original enough to be distinguished as an autonomous discipline. Anyway, it is so unique among the multifarious film genres that a maker of animated films finds it easier to communicate with a representative of the fine arts who does not make films than with someone who makes feature films or documentaries. For that reason it may be better to opt for the term “animated visual art”, i.e. produced not solely by means of a brush and canvas but also a cine-camera, a projector, and a screen.

M.G.: You have designed settings for all your films. Does it make you feel an artist?

W.G.: Quite a blunt question. All my artistic experience is subordinated to the film. I do not practice art in any other form. Hence I feel at once an artist and a film maker, one inseparable from the other. I would have no time for painting, graphic art or drawing. Film making is very timeconsuming. Maybe I am not very well organized, but it takes all my time.

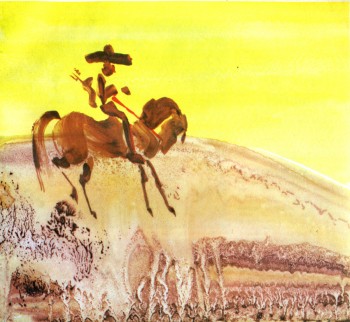

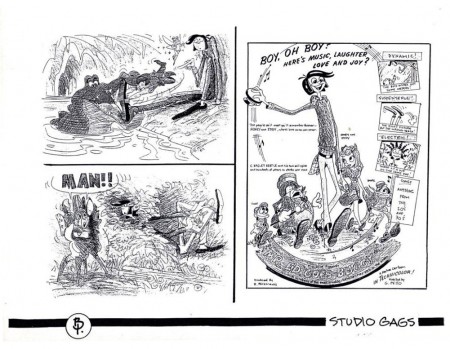

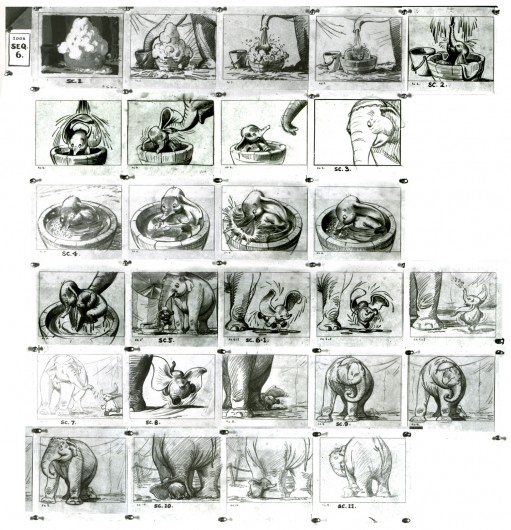

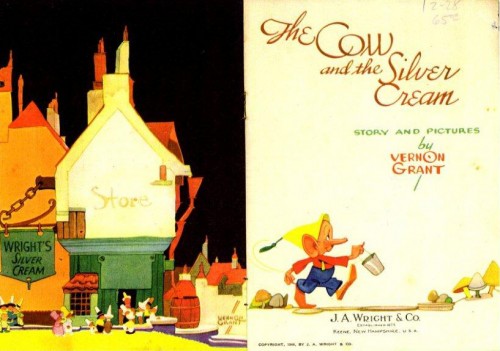

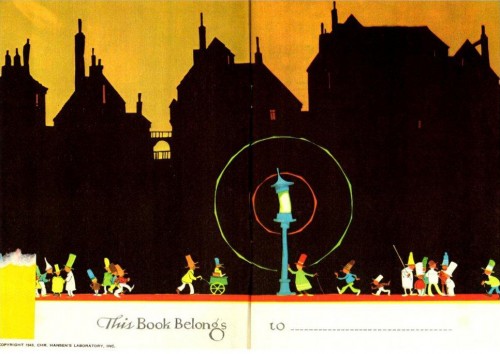

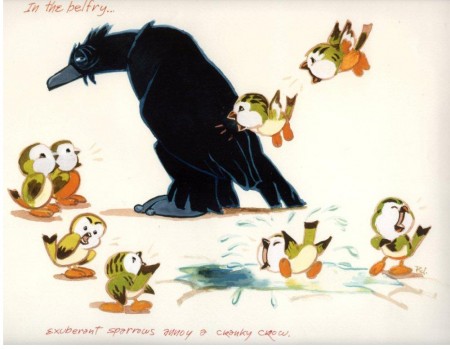

Illustrations:

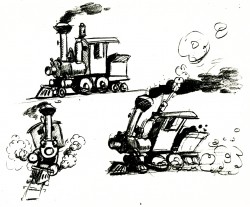

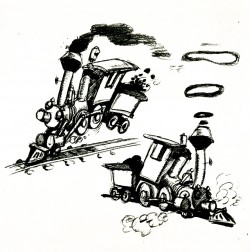

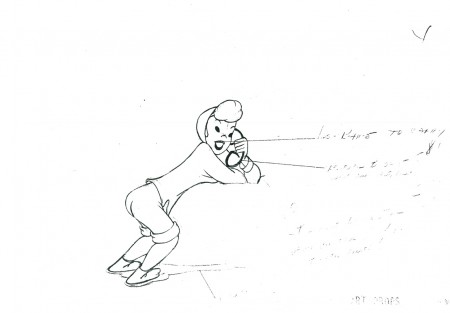

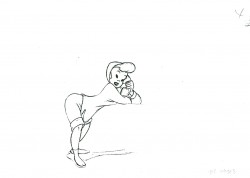

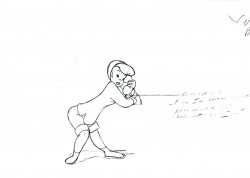

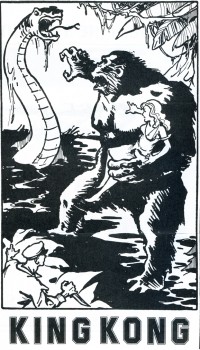

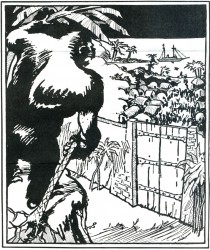

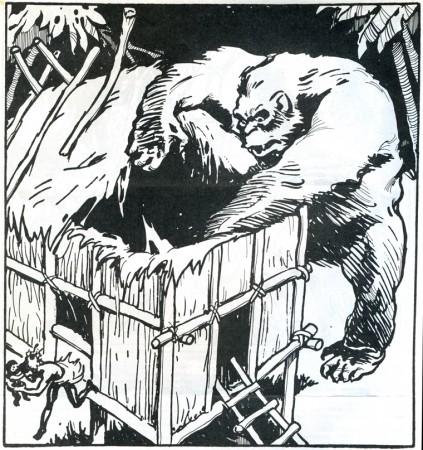

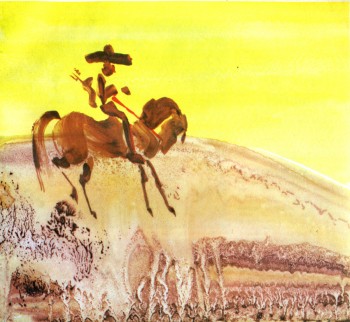

1. The Old Cowboy

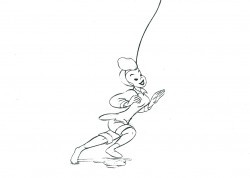

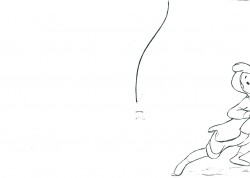

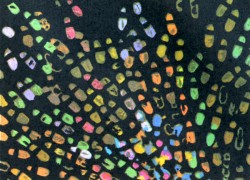

2. Footprints

WITOLD GIERSZ: FILMOGRAPHY

1956: TAJEMNICA STAREGO ZAMKU (The Mystery of the Old Castle),

1957: W DZUNGLI (In the Jungle),

1958: PRZYGODY MARYNARZA (A Sailor’s Adventures),

1959: WIOSENNE PRZYGODY KRASNALA (A Dwarf’s Spring Adventures), NEONOWA FRASZKA (The Neon Trifle),

1960: MALY WESTERN (The Little Western-prizes: Turin, Leipzig, Cracow; honorary mentions: Cork, Necochea; diplomas: San Francisco, Melbourne, Oberhausen),

1961: SKARB CZARNEGO JACKA (Black Jack’s Treasure,

1962: OCZEKIWANIE (Expectation — prizes: Cannes, Moscow; diploma: Edinburgh), PODARTA KSIA.ZKA (A Torn Book), DI-NOZA UR Y (Dinosaurs – prizes: Cracow, Alexandria),

1963: W PIASKACH PUSTYN1 (In the Sands of the Desert), CZERWONE I CZARNE (The Red and the Black – prizes: Oberhausen, Cracow, Cannes, Bratislava, Santa Barbara; honorary mention: Montevideo; diplomas: London, Turin, Edinburgh, Cork, Melbourne, Oberhausen; the prize of the “Film” weekly), MADAME SOPRANI,

1964: KLOPOTY Z CIEPLEM (Troubles with Heat – prizes: Lodz, Cracow), LADIES AND GENTLEMEN (an honorary mention La Felguera),

1965: KORZEN (The Root),

1966: KARTOTEKA (The Card-Index),

1967: KON (The Horse -prizes: Cracow, Mamaia, Adelaide, Honolulu; diplomas: Melbourne, Edinburgh),

1968: ADMIRAL (The Admiral), WYCIECZKA ZA MIASTO (The Journey out of the City – prize: Poznah), PRZE-PROWADZKA DOMINIKA (The Removal of Dominik),

1969: INTELEKTUALISTA (The Intcllc-ctualist – prize: Paris, diploma: Venice), ROZBIT-KOWIE (The Castaways), OTO ZYCIE (That is Life -both films done in Yugoslavia with Milan Ljubic),

1970: WSPANIAtY MARS7 (The Maenificent March – prize: foznanj, iy/i: (The Perfect Driver), 1972: KASKADER (The Stunt-man – diploma: Cracow),

1973: RODZINA IN-DONEZYJSKA (An Indonesian Family – commissioned in Norway), STARY KOWBOJ (The Old Cowboy – prizes: Poznan, Cork),

1974: SLADY (Footprints),

1975: POZAR (The Fire – prizes: Cork, Poznan, Teheran; honorary mention: Jelenia Gora; diploma: Oberhausen; the special prize of the President of the Board of Culture),

1976: WIELKIE KOTY (The Big Cats – commissioned in the USA),

1978: SKANSEN (Ethnographical Museum), PROSZE SLONIA (Please, Elephant; full-length – prizes: Poznan, Varna; the Zenon Wasilewski prize).

1

1 7

7 8

8