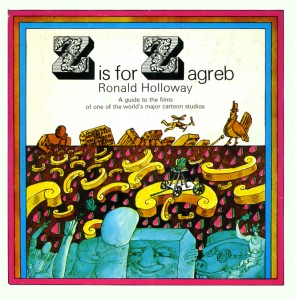

- Last week I posted a short bit from the excellent book by Ronald Holloway, Z is for Zagreb. We saw the bio of one of the principal leaders of this studio/school. I wanted to jump a couple of years and give the bios of two others in Zagreb whose work I particularly like. One, Zlatko Grgic, did one of my favorite Zagreb shorts, Tup Tup.

I precede those bios with another short piece from Holloway’s book.

Individuality

Was it really a “school”? Or a group of people who liked working together? Perhaps there’s no distinction, but the Zagreb cartoonists are proud of their individuality and even today work as free agents. Most of their films bear an individual mark, and despite tempting offers from abroad they prefer the climate of a free atmosphere to exchange ideas and seek help when they need it. The Zagreb studio is not a “school” but a “family.” No other loose climate of friendship and trust exists in animation—and the Zagreb artists had to fight to keep it that way.

Was it really a “school”? Or a group of people who liked working together? Perhaps there’s no distinction, but the Zagreb cartoonists are proud of their individuality and even today work as free agents. Most of their films bear an individual mark, and despite tempting offers from abroad they prefer the climate of a free atmosphere to exchange ideas and seek help when they need it. The Zagreb studio is not a “school” but a “family.” No other loose climate of friendship and trust exists in animation—and the Zagreb artists had to fight to keep it that way.

Soon after the balmy days of the Cannes Festival and an awakening among their own critics to the importance of their work, the management of Zagreb Film changed and instead of increased support they were greeted with open envy and distrust. Suppose the animation department became strong enough to take over the entire company? As preposterous as that sounds, it makes sense in light of the fact that animation was the first international breakthrough for the Yugoslav fiirn industry. The cartoonists were celebrated in every national newspaper. And so to forestall any possible insurrection, the management brought in “artistic directors” to keep a tight rein on the real artists in the studio.

A further argument could be made for the “artistic director” by pointing out the directorial posts of non-designers Mimica and Kostelac. Mimica was to distinguish himself in the future through Marks, and Kostelac was to do the same through Kostanjsek. Who were actually responsible for these films: the director or the designer, or possibly the team together? And in the Vukotic-Kolar team it was even more difficult to decide, because they both were designers. In any case, the management overlooked the fact that each of these individuals gave as much as they took, and decided that all an “artistic director” had to do was find an idea and pull the work out of a designer. Animation was as simple as that.

It was an unfortunate phase, and one that even today appears confused and knotty. Vukotic and Mimica remained essentially unaffected and both worked in complete harmony with the units under them. Two other directors, Dragutin Vunak and Ivo Vrbanic, were not exactly new to the ranks and for the most part were successful in forming new units. The Neugebauer Brothers had left for Germany, and some new blood was needed to replace them. The designers were not confident to start out on their own, and didn’t always mind if someone else took all the risks. The trouble arose when two young graduates of the theatrical academy. Mladen Feman and Bohslav Mrksic, were brought in by the management to run their own show without any previous experience at ail. It is worthwhile to compare the careers of Vunak, Vrbanic, Feman and Mrksic.

Vunak came from Interpublic and fitted in well with Zagreb Film’s advertising department. He had previously worked with Dovnikovic and they collaborated on the picture-book A Small Train. Later he brought in an artist friend, Aleksandar Srnec. to help create the experiment film The Man and His Shadow. He gave young Ante Zaninovic his first start with Cow on ihe Frontier, appearing at a crucial time in Zagreb’s history and saving the studio from total eclipse. He fitted a superb idea to the offbeat talents of painter-sculptor Zvonimir Loncaric and made the credible Between Lips and Glass. In between he made a few bad films. The interesting factor is that each of Vunak’s successful films is in a completely different style, which leads to the conclusion that Vunak is only as good as his designer. But he nearly always picked the right designer lor the right idea, and they got along well together. Th^films could not have been completed without him.

Ivo Vrbanic is not quite in the same category. He made too many films too quickly, and most of them turned out badly. His name first appears as a co-writer of Vukotic’s satire on the horror film, The Great Fear, and he surprisingly enough has the same credit on Mimica’s Alone. He formed a brief partnership with Dovnikovic on Romeo and Juliet, and then seemed to hit the right combination with painter-designer ivo Kaiina on children’s films; A Ballad. All the Drawings of the Town, and Dance on the Hoof. He was the perfect answer for the departing Neugebauers, but he was never able to reach the heights of A Ballad and All the Drawings of the Town again. The team of Vrbanic-Grgic—Adam and Eve, Love and Film, The White Mouse, and The Rivals—shows a general discomfort with satire, although there are many nice touches throughout. The biggest mistake of Vrbanic’s career was coming into contact with the volcanic Vlado Kristl. They are billed as co-directors of La Peau de Crfagrin. but Vrbanic has very little to do with the cartoon as a whole and they were in constant disagreement from beginning to end. Vrbamfi as an artist always seems to be out of his depth in the adult cartoon but he probably would have been successful in the old Duga days.

Mladen Feman was also assigned to satire—and was the first to run headlong into the temper of Kristl. Kristl, one of the country’s leading abstract artists, had just returned from a trip through Europe and South America, and was not about to be suppressed by young graduates from the theatrical academy. They battled throughout The Great Jewel Robbery, a follow-up parody on Vukotic’s successful Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun that turned out to be better artistically and commercially than the first one. He next tried to supervise the formidable Marks in a follow-up to Vukotic’s Cowboy Jimmie, and again it was clear who was really in control of the film. He made one last attempt to prove his own worth on the doomed Inspector Mask series by directing, designing and animating independently, then left the feature cartoon for good. It can be argued in his favour that Feman never really had a chance to prove his worth under the prevailing system.

The worst case of artistic suicide was the strange career of Borislav Mrksic. He was matched with veteran designer Ismet Voljevica on the ill-fated The Kite, which is in the running for the ugliest film ever made and should be shown at the Annual Congress of Artistic Directors. After this disaster Mrksic disappeared from the studio, and Feman and Vrbanic were eventually to follow him.

Toward the end of the Fifties articles began to appear in the newspaper condemning the policy of suppressing the studio’s leading talent. Fadil Hadzic led the crusade, and he even went so far as to include Vukotic and Mimica among the guilty parties. All the credit for animation should go to the designer, he contended—an equally fallacious argument- But after a while the management went through another change and the integrity of the artists was restored. An axiom was adopted at the studio: an animated film is an author’s film. The ideal situation was for an author to be responsible for everything, from first conception through design and animation. Direction and animation need not necessarily be separated. It is an axiom that has lasted until today.

Only it’s too bad it had to cost the talents of the studio’s best artist.

________________

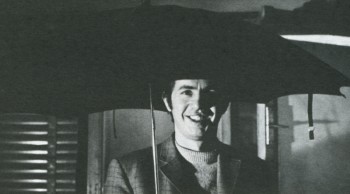

Zlatko Grgic

(Born 1931 in Zagreb).

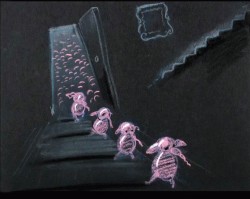

Studied journalism and law before turning to cartoons in 1951. He contributed some cartoons to Kerempuh and assisted as animator on Kostelac’s Opening Night (1957) and Encounter in a Dream (1957). He was the chief animator on Norbert Neugebauer’s The False Canary (1958), and Vukotic’s The Great Fear (1958) and Revenger (1958). He was Vukotic’s designer and animator for Cow on the Moon (1959), and later directed under Vukotic’s supervision A Visit from Space (1964) and The Devil’s Work (1965). He formed a team with Vrbanic in 1 960 and designed and animated for him Adam and Eve (1960). Love and Film (1961), and The White Mouse (1961), and animated his Rivals (1962). He was the animator on Vrbanic-Kristl’s La Peau de Chagrin (1960). He began as an independent director on an advertising film in 1960. designed and animated Branko Ranitovic’s children’s film Nisu Znaii jer su Mali (1960) for Zora Film, and directed in the Case (1961) and Inspector Mask (1962) series. Forming a team with Stalter they co-directed The Fifth (1964) and Scabies (1969). Staiter was Grgic’s background painter on The Musical Pig (1965) and Grgic was Stalter’s animator on Boxes (1967). Grgic also helped Dovnikovic on his script for Krek (1967), after Dovnikovic assisted him on the script for The Musical Pig.

Studied journalism and law before turning to cartoons in 1951. He contributed some cartoons to Kerempuh and assisted as animator on Kostelac’s Opening Night (1957) and Encounter in a Dream (1957). He was the chief animator on Norbert Neugebauer’s The False Canary (1958), and Vukotic’s The Great Fear (1958) and Revenger (1958). He was Vukotic’s designer and animator for Cow on the Moon (1959), and later directed under Vukotic’s supervision A Visit from Space (1964) and The Devil’s Work (1965). He formed a team with Vrbanic in 1 960 and designed and animated for him Adam and Eve (1960). Love and Film (1961), and The White Mouse (1961), and animated his Rivals (1962). He was the animator on Vrbanic-Kristl’s La Peau de Chagrin (1960). He began as an independent director on an advertising film in 1960. designed and animated Branko Ranitovic’s children’s film Nisu Znaii jer su Mali (1960) for Zora Film, and directed in the Case (1961) and Inspector Mask (1962) series. Forming a team with Stalter they co-directed The Fifth (1964) and Scabies (1969). Staiter was Grgic’s background painter on The Musical Pig (1965) and Grgic was Stalter’s animator on Boxes (1967). Grgic also helped Dovnikovic on his script for Krek (1967), after Dovnikovic assisted him on the script for The Musical Pig.

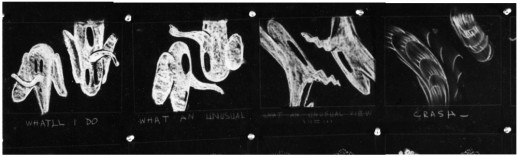

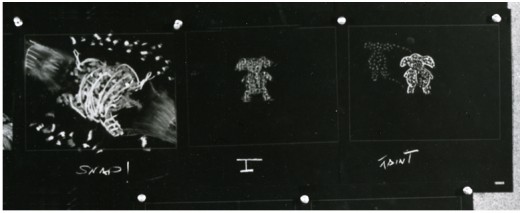

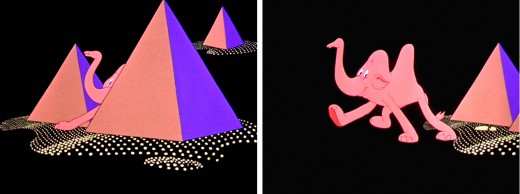

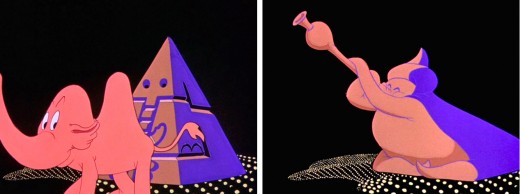

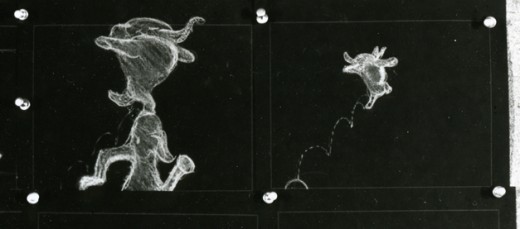

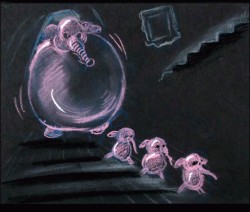

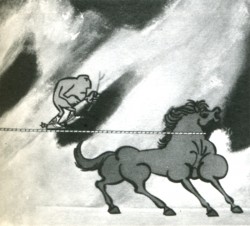

After The Musical Pig Grgic has directed independently Little and Big (1966), Inventor of Shoes (1967). and Twiddle-Twaddle (1968), and co-directed with Branko Ranitovic Tolerance (1967) and The Suitcase (1969) (for Viba Film). Inventor of Shoes prompted the Professor Balthasar series (1969), the studio’s first successful adventure into a series and the combined work of Grgic. Kolar and Zaninovic. His mini mini creation is Maxi Cat. A master of free, dynamic animation with numerous twists, witty gags and unexpected turns. Grgic is one of the subtlest poets in the animation business.

After The Musical Pig Grgic has directed independently Little and Big (1966), Inventor of Shoes (1967). and Twiddle-Twaddle (1968), and co-directed with Branko Ranitovic Tolerance (1967) and The Suitcase (1969) (for Viba Film). Inventor of Shoes prompted the Professor Balthasar series (1969), the studio’s first successful adventure into a series and the combined work of Grgic. Kolar and Zaninovic. His mini mini creation is Maxi Cat. A master of free, dynamic animation with numerous twists, witty gags and unexpected turns. Grgic is one of the subtlest poets in the animation business.

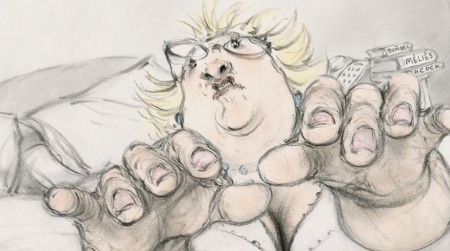

Nedeljko Dragic

(Born 1936 in Paklenica).

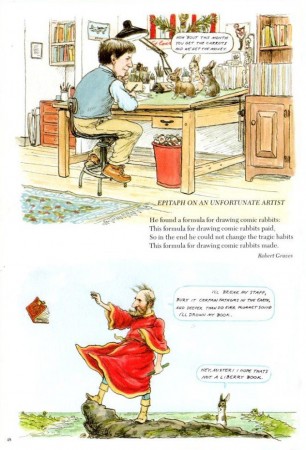

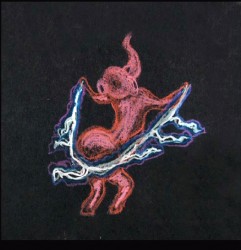

Studied law in Zagreb and worked from 1953 for a number of newspapers and journals as cartoonist. He published in 1964 a book of his cartoons, Alphabet for Illiterates, and has won awards for his “anti-” comic strips. His first contribution to the Zagreb studio was as designer for Ranitovic’s The Dreamer (1961), Kostelac’s Cupid (1961), and Vrbanic’s Rivals (1962). He designed and animated in the Inspector Mask series (1962), and returned to the studio again in 1 964 to design Pejakovic’s Once upon a Time There Was a Dot. His first independent cartoon was Elegy (1965), taken out of a page of his cartoon book, and from a Mimica script he created

Studied law in Zagreb and worked from 1953 for a number of newspapers and journals as cartoonist. He published in 1964 a book of his cartoons, Alphabet for Illiterates, and has won awards for his “anti-” comic strips. His first contribution to the Zagreb studio was as designer for Ranitovic’s The Dreamer (1961), Kostelac’s Cupid (1961), and Vrbanic’s Rivals (1962). He designed and animated in the Inspector Mask series (1962), and returned to the studio again in 1 964 to design Pejakovic’s Once upon a Time There Was a Dot. His first independent cartoon was Elegy (1965), taken out of a page of his cartoon book, and from a Mimica script he created

the impressive Tamer of Wild Horses (1966). But the pure Dragic is to be found in Diogenes Perhaps (1967) and Passing Days (1969), winners of numerous international awards. He scripted Blazekovic’s The Man Who Had to Sing (1970) and did the backgrounds for Dovnikovic’s The Flower Lovers (1970). He did the first mini mini films. Per Aspera ad Astra and Striptease (both in 1969), to introduce the studio’s annual production and started the creative one-minute fad. Dragi6′s satirical slams are unmatched in animation, stemming from his rich newspaper experience. He balances his sharp criticism of the world’s inhumanity with poetic touches of melancholy and nostalgia for a saner life.

the impressive Tamer of Wild Horses (1966). But the pure Dragic is to be found in Diogenes Perhaps (1967) and Passing Days (1969), winners of numerous international awards. He scripted Blazekovic’s The Man Who Had to Sing (1970) and did the backgrounds for Dovnikovic’s The Flower Lovers (1970). He did the first mini mini films. Per Aspera ad Astra and Striptease (both in 1969), to introduce the studio’s annual production and started the creative one-minute fad. Dragi6′s satirical slams are unmatched in animation, stemming from his rich newspaper experience. He balances his sharp criticism of the world’s inhumanity with poetic touches of melancholy and nostalgia for a saner life.

The unfortunate part of the book is that it was written in 1972 and doesn’t detail, as a result, the most important part of both of these artists’ careers.

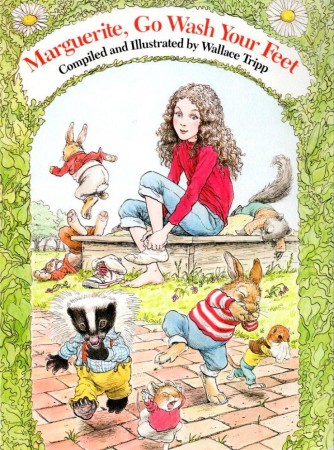

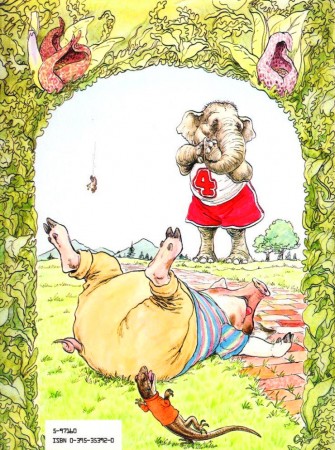

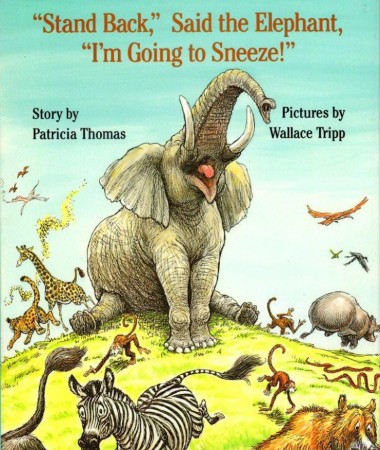

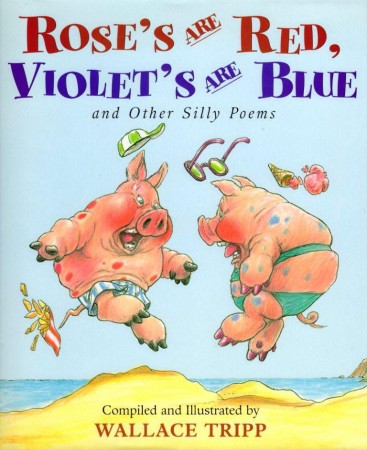

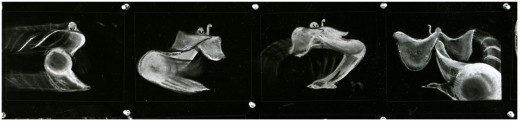

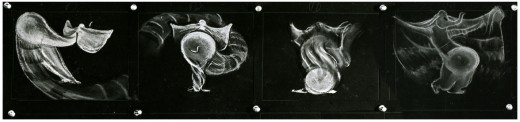

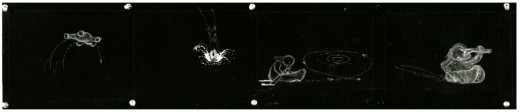

Images:

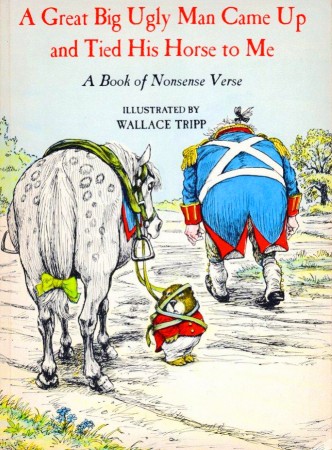

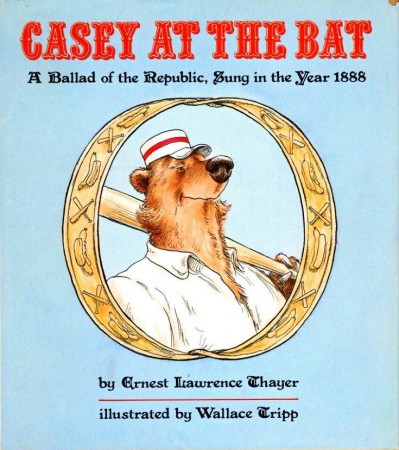

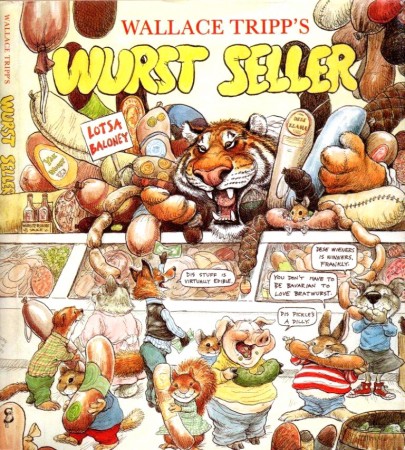

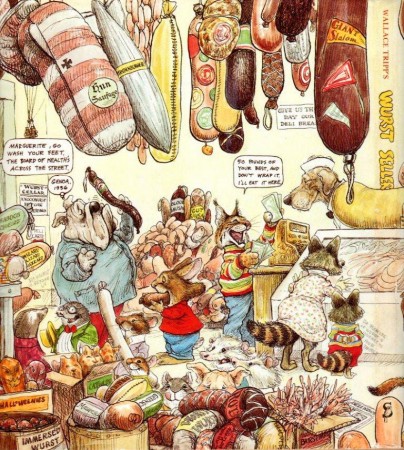

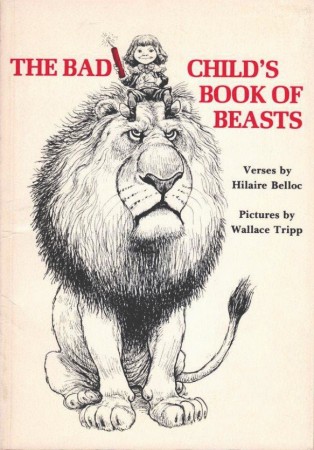

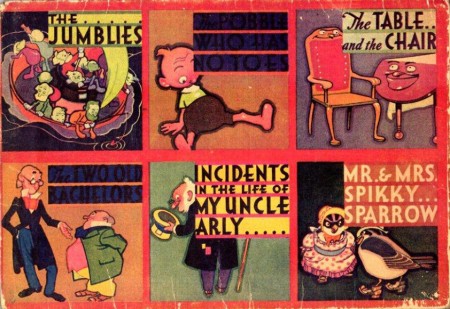

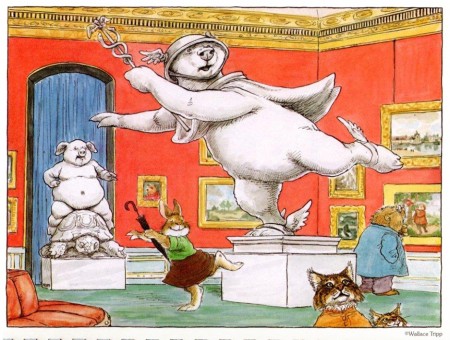

1. Book cover – Z is for Zagreb

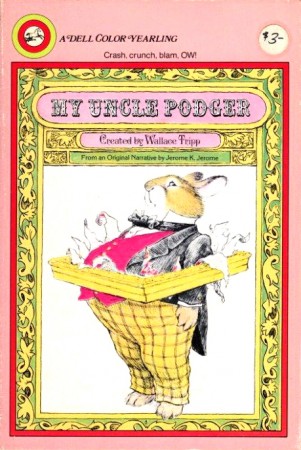

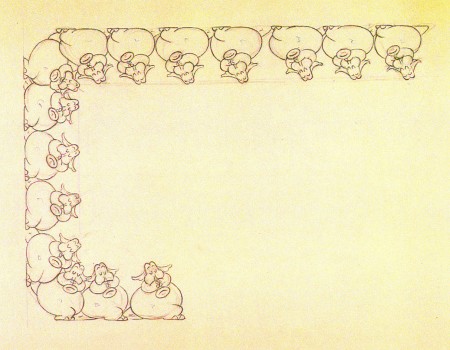

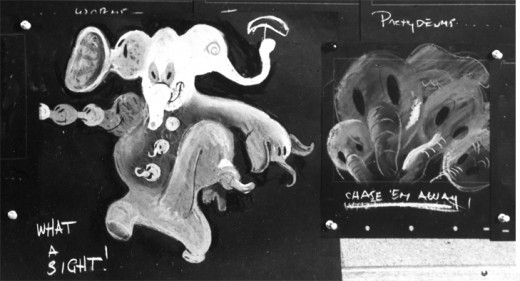

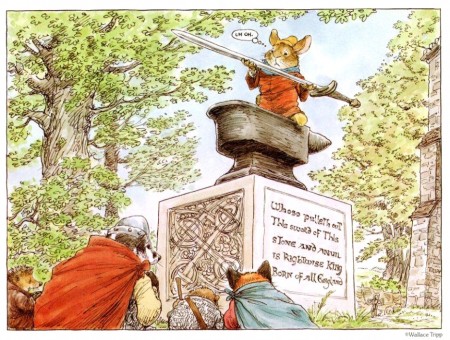

2. Zlatko Grgic

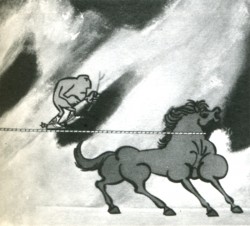

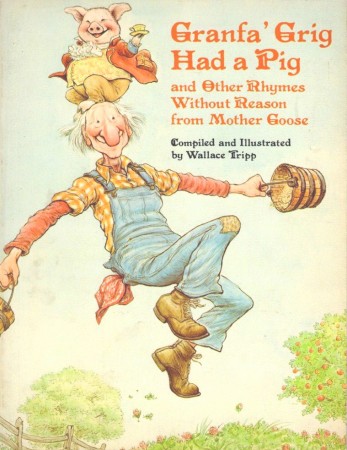

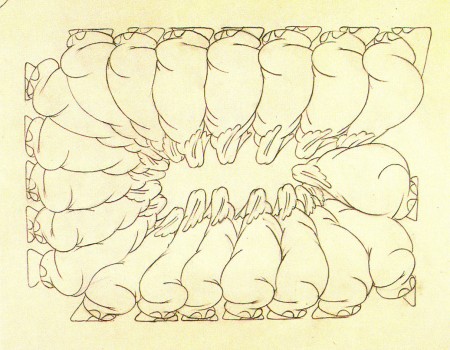

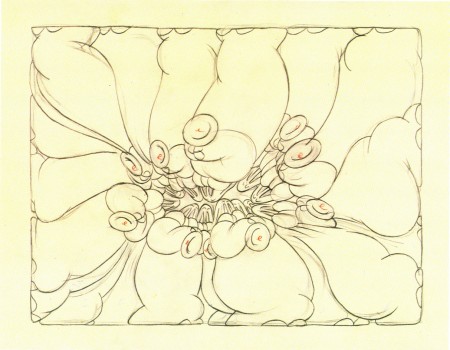

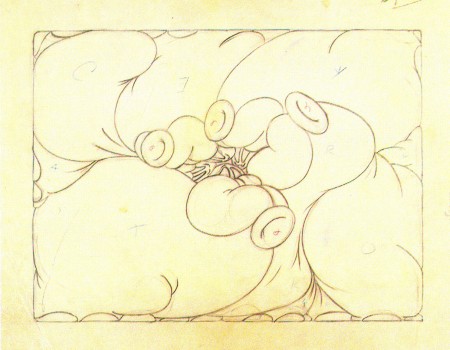

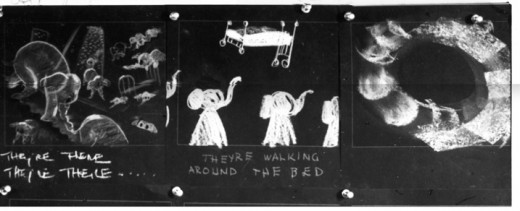

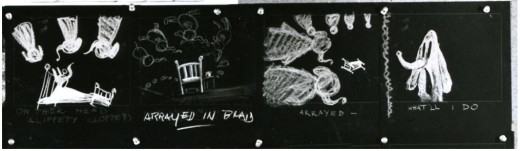

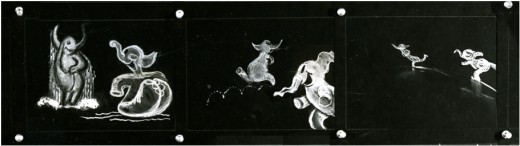

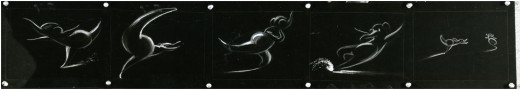

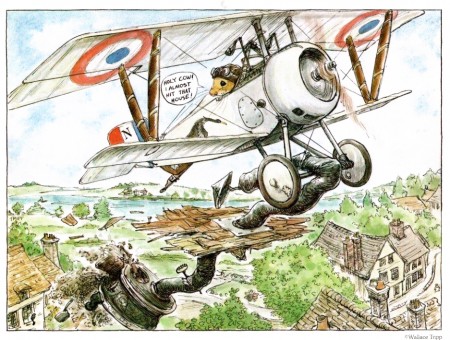

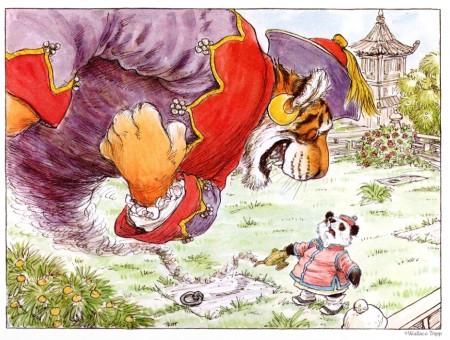

3. The Inventor of Shoes

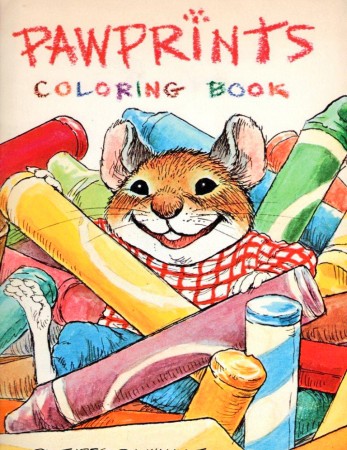

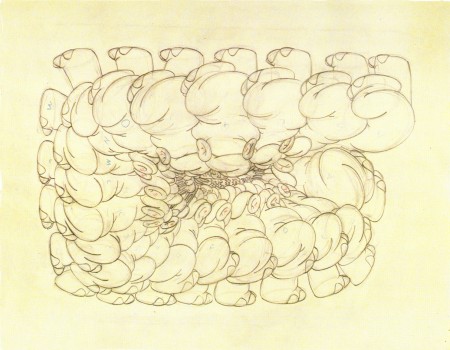

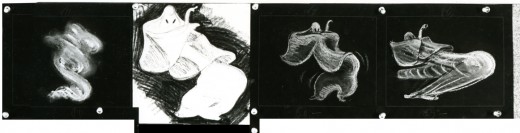

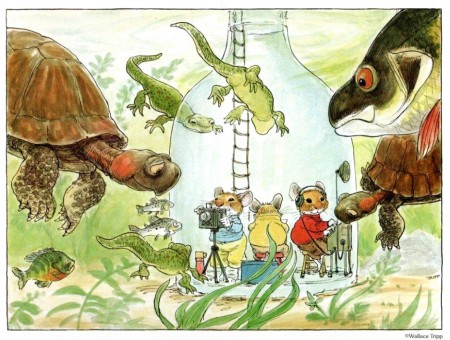

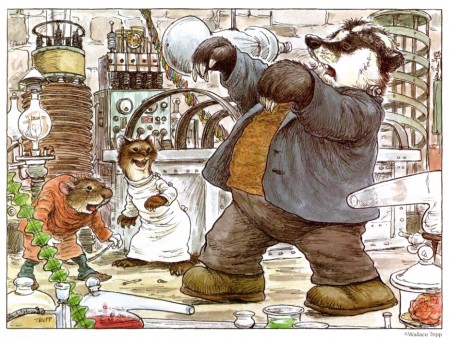

4. Nedeljko Dragic

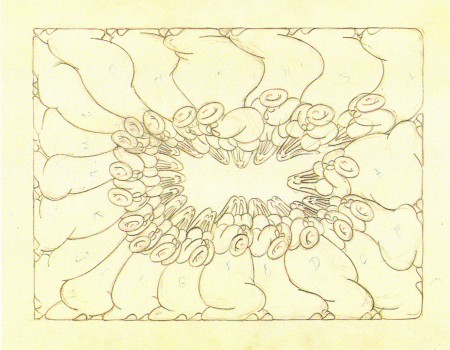

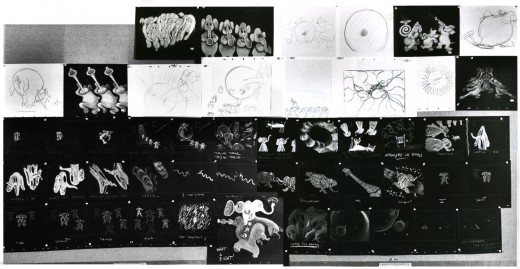

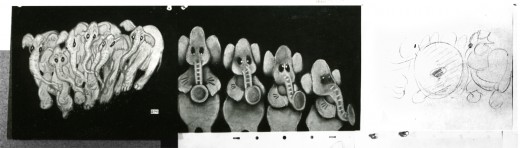

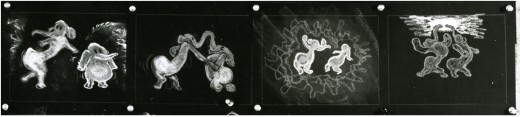

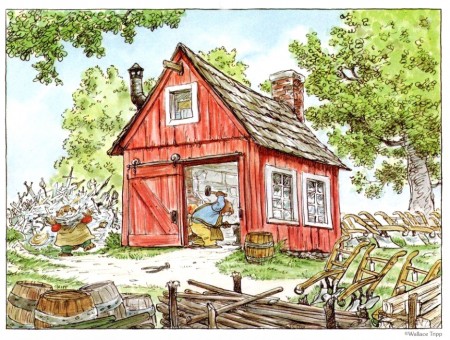

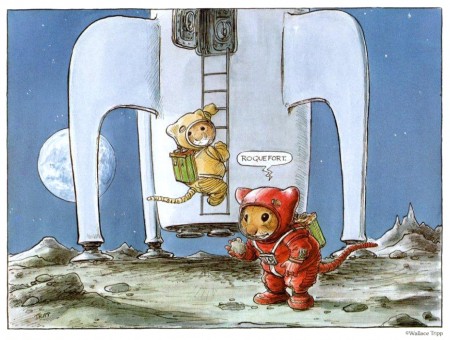

5. Tamer of Wild Horses

1972

1972

The photography by the great Gregg Toland has to be second only to his work on Citizen Kane. The deep focus imagery is used to pull strong emotion and tell the story more simply. As Homer (Harold Russell) and Butch (Hoagy Carmichael) play chopsticks in the foreground, we’re watching Fred (Dana Andrews) make a desperate and sad phone call far in the distance of the bar. While Homer and Wilma marry to the right of the screen, Fred, in the foreground, is watching Peggy (Teresa Wright) in the distance. There are those scenes of Fred walking among the detritus of the Air Force as hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of fighter planes line up for destruction.

The photography by the great Gregg Toland has to be second only to his work on Citizen Kane. The deep focus imagery is used to pull strong emotion and tell the story more simply. As Homer (Harold Russell) and Butch (Hoagy Carmichael) play chopsticks in the foreground, we’re watching Fred (Dana Andrews) make a desperate and sad phone call far in the distance of the bar. While Homer and Wilma marry to the right of the screen, Fred, in the foreground, is watching Peggy (Teresa Wright) in the distance. There are those scenes of Fred walking among the detritus of the Air Force as hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of fighter planes line up for destruction.

In writing his piece, Mike gets it right, I think, about changes in Pixar (post sellout to Disney) and Disney animation. It hasn’t been all good, and it looks like Bird is looking to improve his profile and financial fortunes by leaving animation behind. The same is probably true of Andrew Stanton who is now scheduled to direct a live action John Carter of Mars for Pixar. (Remember the animated tests Clampett did of this story back in the ’30s? It looked like the Fleischer Superman, years earlier.) Although in directing live action for Pixar, Stanton puts his toes in the water rather than jumping.

In writing his piece, Mike gets it right, I think, about changes in Pixar (post sellout to Disney) and Disney animation. It hasn’t been all good, and it looks like Bird is looking to improve his profile and financial fortunes by leaving animation behind. The same is probably true of Andrew Stanton who is now scheduled to direct a live action John Carter of Mars for Pixar. (Remember the animated tests Clampett did of this story back in the ’30s? It looked like the Fleischer Superman, years earlier.) Although in directing live action for Pixar, Stanton puts his toes in the water rather than jumping.