- Earlier this week, I’d posted an excellent piece by Mike Barrier on the work of the Hubleys. This article was taken from a 1977 Millimeter Magazine animation issue. In that same issue, is an article about the history of the TV commercial. There’s a lot of good information in the piece and the shortened history of a lot of important studios that many of you are unfamiliar with. Unfortunately, it also mentions a lot of ads you may not be familiar with. But there’s plenty there in the packed piece. So I thought it a good idea to put this info out there.

Here’s the piece by Arthur Ross.

The Animated Comercial:

A Retrospective View

by Arthur Ross

ANIMATE, according to the time-honored Webster’s definition, means “to give natural life to; to give spirit to; to stimulate; to rouse; to prompt; to impart an appearance of life, as to animate a cartoon.”

And that is exactly what animated TV commercials have been doing for the past 30 years. They have given life, spirit, and verve to the selling of thousands of products both in America and abroad.

Psychologically speaking, they work by expanding the fixed limits of reality, by creating new and exciting worlds of fun and fantasy, and by captivating the viewer with fresh perspectives that reinforce our basic drives and motivations for love, success, beauty, comfort, and self-esteem.

During the course of a single 60 second spot, we see 1,440 individual pictures, or frames, come to life! Often with the kind of humor, or whimsy, or charm that speaks to our unguarded and childlike selves, and in some instances, even to the deepest recesses of our unconscious.

That is precisely why they are so potent a sales tool for industry, an educational device for schools, and an entertainment vehicle unto themselves. They work by playfulness, destroying all logical opposition to the messages they may contain.

They dazzle our senses and charm us into belief. Or, at least, they help suspend our disbelief in the ideas they put forth. They are 20th century dreams — dreams that money can buy!

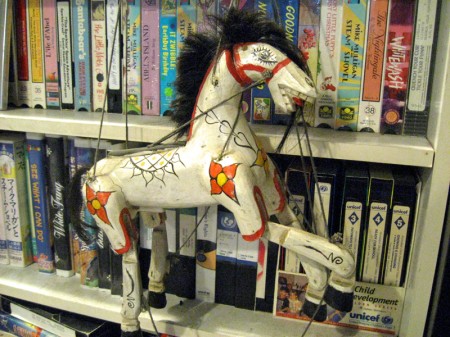

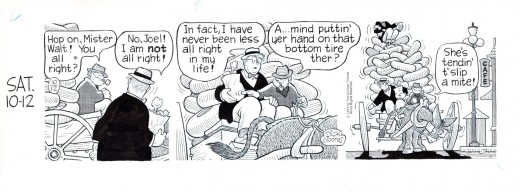

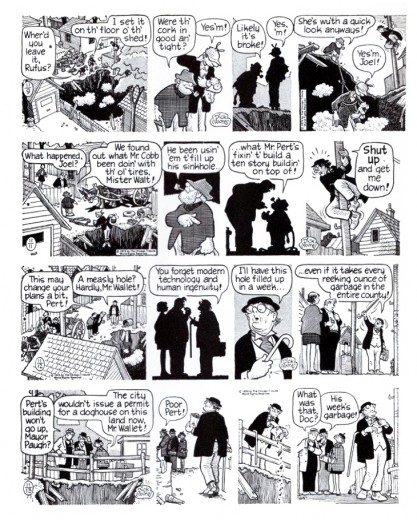

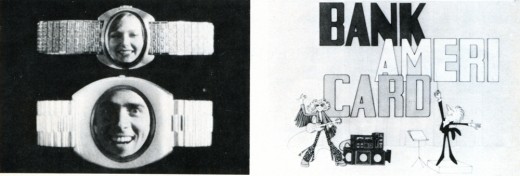

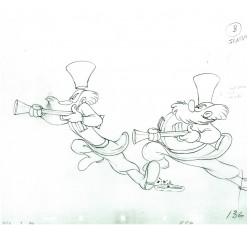

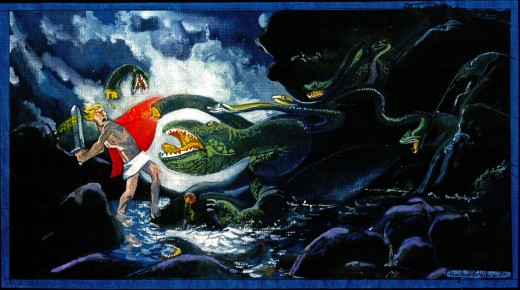

1. Object Animation: Speidel’s “Faces In The Watches”

created by John Gati of Action Pictures.

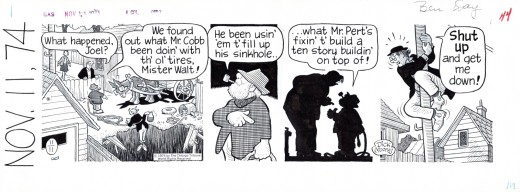

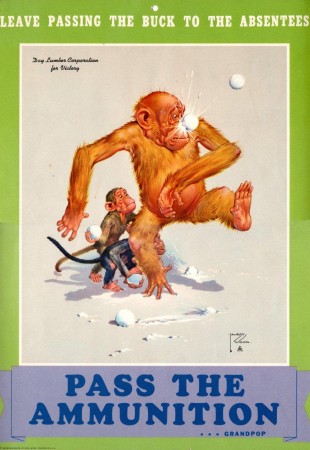

2. West Coast animation: Bank Americard (FilmFair) 1961-1976

While they operate on our most primative emotional level, animated commercials are highly sophisticated forms of art — employing words, graphics, color, motion, sound, music and symbols to activate the sale of goods and services.

Some of America’s foremost art talent has worked in the field at one time or another, including Saul Steinberg, John Hubley, William Steig, Saul Bass, to name a few.

The earliest animation in the forties was generally quite conventional — literally cartoon commercials of the straight Disney school of animation. It was essentially an extension of theatrical animation such as characterized the products of Warner Brothers, Paramount, MGM, and Disney at the time. Its novelty was successful and proved animated characters could sell products as well as live spokespeople. Everything was executed in glorious black and white, since color on TV was still years away. Commercial studios began to emerge in the late ’40s and early ’50s to supply the demand for animated spots — among them Academy Pictures, Shamus Culhane, Bill Sturm Studios, Film Graphics turning out such early “hall of famers” as the Ajax “Down the Drain” Bubbles and Mott’s “Singing Apples”.

In the early “50s a new trend entered TV commercials when UPA, creators of Gerald McBoing-Boing for theaters, introduced its unique avant-garde style of animation breaking away from the more conventional school of Disney design and execution.

We had the pleasure in the early ’50s of working personally1 with ex-UPA star John Hubley on some of the most successful of these avant-garde spots, including those for Speedway 79 gasoline, Altes Golden Lager Beer and Faygo Beverages (for the W.B. Doner agency in Detroit) as well as Chevrolet (for Campbell-Ewald, again in Detroit.) Other notable avant-garde entries during this period included the famous Saul Steinberg Jello “Busy Day” spot, as well as the classic Bert and Harry Piels spots (for Young and Rubicam).

Continuing through the mid ’50s, two trend-setting studios emerged when John Hubley formed Storyboard Inc. and Abe Liss joined forces with Sam Magdoff to start Elektra Films. Hubley continued his classic style with such winners as Heinz Worcestershire Sauce’s “Tongue-tied Spokesman”, Ford “It’s a Ford” series, and Maypo’s “I Want My Maypo” commercial. Elektra came forth with highly experimental works, creating new breakthroughs in photo-animation, multiple image and optical effects, and totally fresh avenues of design. During this time Elektra spawned such outstanding animation and graphics talents as Jack Goodford, Pable Ferro, Cliff Roberts, the Canattas, Lee Savage, Phil Kimmelman, and Hal Silvermintz, as well as Arnie Levin, Howard Beckerman, and Mordi Gerstein. Among the outstanding Elektra efforts of this era were the NBC Peacock, the legendary “Talking Stomachs” Alka Seltzer spot designed by R.O. Blechman, as well as award-winners for Chevron, Esso, Chevrolet, and Alcoa. One notable achievement, I fondly recall, was a 60-second spot done for the United States Army “Great Moments” series (which I had the pleasure of writing and producing) in which Elektra’s people (including the late Len Appleson) recreated the entire Louis-Schmelling Championship fight with stills quick-cut to the rapid beat of music and crowd cheers. It was a montage breakthrough that Sergei Eisenstein would have been proud of.

Following the success of Storyboard, Inc. and Elektra, more top studies and talent emerged in commercial animation. Pelican films emerged under the able leadership of Jack Zander and did notable work for American Motors, Volvo (designed by Mordi Gerstein) and Alka Seltzer (“The Blahs” designed by cartoonist Willilam Steig.)

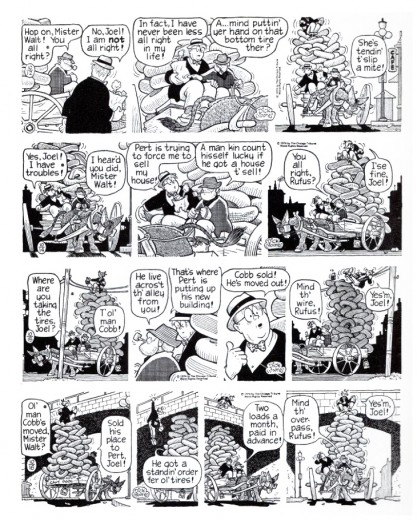

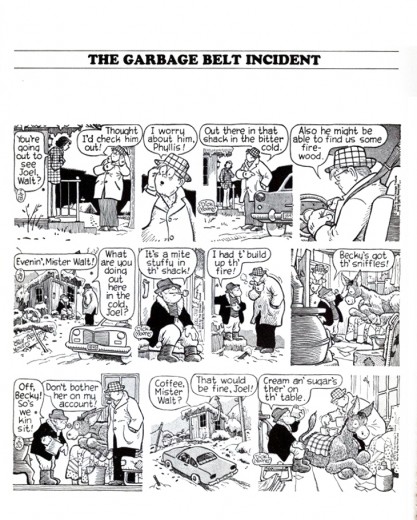

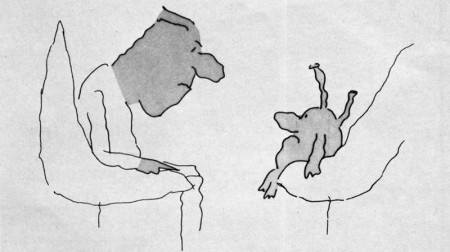

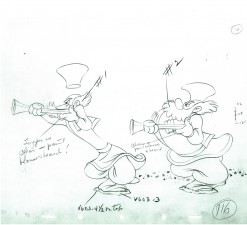

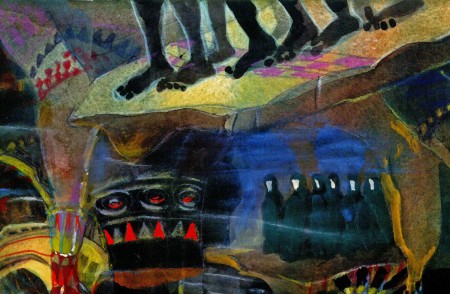

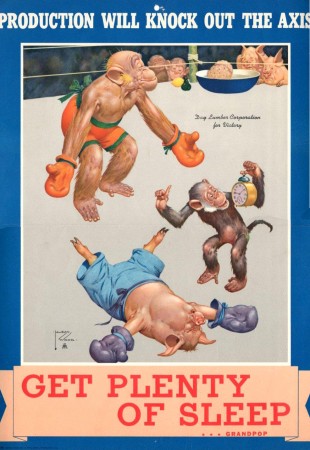

Use of famous cartoonists and illustrators in TV Commercials:

Still from a commercial made in the 60s by Elektra Productions,

utilizing cartoonist Bill Steig.

Other fine studios of the fifties were those begun by Lars Calonius, Transfilm, Kim-Gifford, Robert Lawrence and Ernest Pintoff — the latter going on to win an Academy Award for “The Critic” some years later. Arnold Stone was a heavy contributor in those years to the Pintoff output, which included excellent animated spots for Proctor-Silex appliances, Yoo-Hoo Chocolate Drink, and The Bell Telephone Company.

These proved to be the “golden years” for commercial animation with many studios maintaining large staffs to cover the growing need for their excellent product. At one point, there was even a shortage of talent available to handle the work load and one had to “wait on line” for delivery.

In the ’60s, the trend increased towards graphics and we saw a sharp decline in traditional animation. New techniques were perfected — like the super quick cuts of Elektra and Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz. The latter also held the industry in marvelous disbelief at its outrageously “insane comic inventions” such as the award-winning “Crazy Hat” commercial for County Fair Bread (which we had the pleasure of producing with them).

Continuing the trend to more limited animation, which UPA orginated as an economical move to cope with the high cost of full animation, studios in the ’60s experimented with photomatics, “squeeze”, semi-abstracts, paper sculpture, and technique of combining live photos with animated bodies (perfected by Paul Kim of Kim-Gifford in a prize winner for the National Safety Council on preventing highway accidents.) Tighter budgets, a declining economy, and a swing away from animation to greater use of realism created massive layoffs in the commercial animation field in the late ’60s and early ’70s — and many good, long-established shops passed from the scene. Smaller one and two-man companies emerged to take their place and this trend continues up to the present day.

It should be pointed out that throughout the ’50s and into the ’60s traditional animation continued as a popular communications tool for many agencies and companies. Outstanding among these was William Tytla Associates. The late Bill Tytla was one of the foremost Disney animators, contributing greatly to the success of such Disney immortals as FANTASIA, PINOCCHIO, SNOW WHITE and DUMBO. In the ’50s, Bill took his talents into the commercial arena and did some outstanding work in the more conventional animation forms. We had the pleasure of working with him in the animation development of the worldwide symbol for Esso, “Happy the Oil Drop,” a fantasy figure that Bill brought to wondrous “life” through his skills as an animation director.

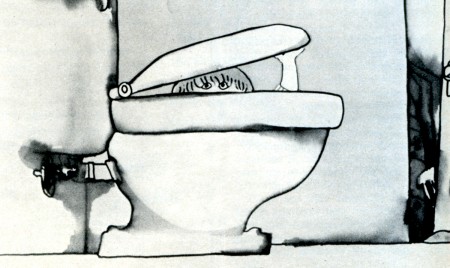

Simplicity of design in 50s & 60s; Still frame from the famous Blechman

“Talking Stomach” Alka Seltzer commercial produced by Elektra in the 60s.

In spite of downtrends in the economy, the late ’60s and early ’70s saw a brilliant new bursting forth of creative energy in animation influenced by Peter Max and the worldwide success of “The Yellow Submarine.”

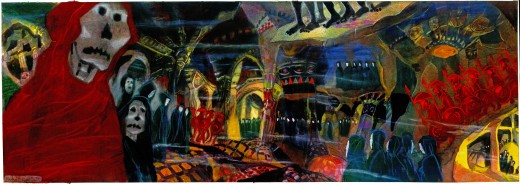

Among the many fine companies that emerged were Focus Productions, which turned out such award-winners as Vote Toothpaste “Dragon Mouth,” designed by Rowland Wilson; Gillette’s “Moveable Features,” designed by Tomi Ungerer, and the Utica Club Beer series designed by Jack Davis and Mort Drucker. In 1972, Phil Kimmelman left Focus to open his own shop, Phil Kimmelman & Associates. Here, along with Bill Peckman, he has turned out some outstanding efforts including the Cheetos Mouse campaign, the Exxon Tiger, and the delicately sensuous Clairol Herbal Essence commercial.

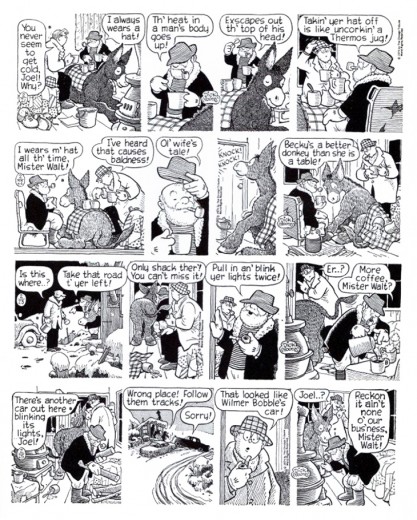

Horror Fantasy in TV commercial animation (1976): Avis Rent-A-Car;

Designer/Director: Mordi Gerstein; Producer Phil Kimmelman & Associates.

Other exciting breakthroughs in the ’70s include the highly graphic look of computer animation, perfected by such companies as Dolphin Productions for use as station and program attractions; rotoscope animation brought to brilliant maturity by Ovation Films in New York and Snazelle Films on the West Coast. The Levi campaign is an outstanding example of rotoscope animation, bringing a fresh new excitement to the field.

On the West Coast, throughout the ’50s and ’60s animation led by UP A, and Storyboard, Inc., continued to expand along with the fine efforts of such companies as TV Spots for Johnson’s Wax, Lucky Lager Beer and L&M Cigarettes; John Sutherland Productions (“A 1580 Atom”); Playhouse Pictures (Ford, Falstaff Beer, H.J. Heinz) Quartet Films (Western Airlines); Animation, Inc. for Oscar Mayer, Soho Boron Gasoline and Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer; and Five Star Productions whose animation department headed by Howard Swift (another ex-Disney man) created some of the earlier TV and cinema commercials for Ford, Pabst, F.T.D., Coca-Cola, as well as bringing Speedy Alka-Seltzer to “life” via the George Pal puppet-type stop motion use of a series of replaceable heads. Interestingly, after a decade of experimenting with other creative directions, Alka Seltzer has just reverted back to using “Speedy” again in its current advertising.

It is an outstanding example of how things come creatively full-circle and how each generation rediscovers the “great ideas” of the past.

Joop Geesink continued to perfect the puppet type animation throughout the fifties, working in Holland for American companies through Transfilm in the United States. His “Brewster, the Goebel Rooster” and Heinz Aristocrat Tomato were two fine creations in this genre.

The use of “stylized” animation-type settings in which live action unfolds was another outgrowth of animation in the late ’50s. S. Rollins Guild whom we had the pleasure of working with at McCann-Erickson in the ’60s contributed greatly to the perfection of this commercial art form for such companies as Nabisco and Coca-Cola. Both series were produced by Bill Sturm Productions in New York.

Black-Lite, while basically a live photographic technique, creates a unique “animation” look to commercials. We had the opportunity of creating and producing the first such black-lite commercial in 1955 for Flagg Brothers Shoes (“Dancing Shoes”) which won numerous Art Director Club Awards for originality and effectiveness. The producing company was Sundial Films, headed by the multi-talented Sam Datlowe. It marked the first commercial assignment for young and talented Jerry Hirshfeld, who later became the ace of the MPO Productions staff, before turning to feature films.

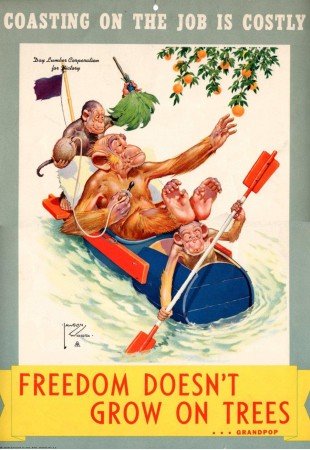

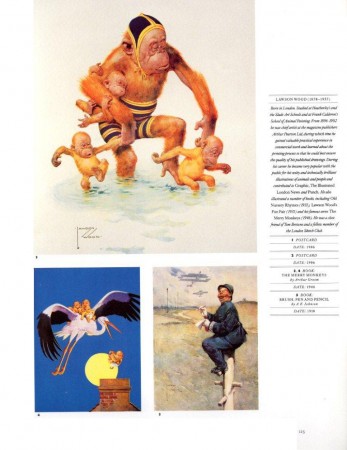

One of the continuing trends in animation today, largely aided by Elektra and Jack Zander in the ’50s, is the use of well-known cartoonists and illustrators from outside the industry. Among the best are Bill Steig, Frank Modell, Charles Saxon, Seymour Chwast, Milton Glaser, and Peter Max, all contributing greatly to the resurgence of animation in the “70s.

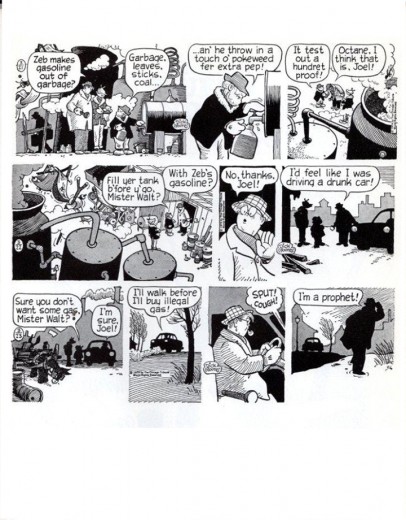

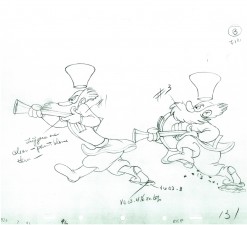

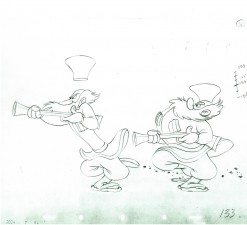

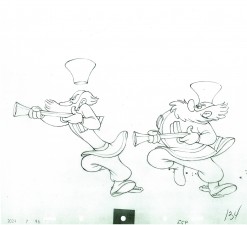

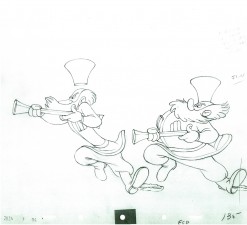

Other outstanding work in animated commercials was achieved on the West Coast by Ray Patin, whose chief animator (another Disney graduate) was Gus Jekel, now the head of Film Fair, Inc. They accomplished some fine efforts for Y&R on Jello in the early ’50s through Jack Sidebotham, one of the really great art directors in the advertising field. These include such classics as “Banana-ana,” and “Chinese Baby.” Ray Patin also turned out the NY AD gold medal Bardahl series, aping Dragnet, as well as noteworthy campaigns for National Bohemian Beer and Jax Beer.

In passing, one must not forget to include in the pantheon of animation producers such fine organizations as Cascade Productions, Playhouse Pictures, Quartet, Imagination, Inc. all of whom executed award-winning series in the ’50s and ’60s.

In the ’60s, Gus Jekel’s Film Fair did noteworthy series for BankAmericard and Bardahl which won the Cannes and Venice Awards. Today, Film Fair does exceptional work with continuing characters, such as Peter Pan (Peanut Butter). Charlie Tuna, Tony Tiger, and the Snap, Crackle and Pop trio for Kellogg’s Like Elektra in the East, Film Fair nurtured a great deal of the best West Coast talent including Art Babbitt, Bob Cannon, Dick Van Benthem, Ken Walker, Fred Wolf, Norm Gottfredson, Ken Champin, and Corny Cole. It is one of the reasons the West Coast continues to do such exciting creative work in the field along with its East Coast counterparts.

One of the long-standing successful animation partnerships in the East has been Paul Kim and Lew Gifford, doing fine work in the field since 1958. Among their top creative efforts are award-winners for Piels Brothers, and the Emily Tipp series. Their Modess a delicate subject with taste, simplicity, and artistry. And their famous Winston “Montage” introduced a 14 way split screen in constant movement to the Winston jingle — breaking exciting new ground in the use of matte work and animation design.

Another top West Coaster is veteran animator Herbert Klynn, President of Format Productions. Herb served 16 years as designer and then Executive Production Manager for UPA, before organizing his own animation company. His Format Productions is active in entertainment series such as the Alvin Shows, the Lone Ranger and Popeye programs, as well as creating titles for such TV shows as I Spy, Smothers Brothers, and The Mothers-In-Law. Among his fine animated TV commercials are those for Max Factor, Post Cereals, Wells Fargo Bank, and Dreyfus Investments. During his tenure with UPA, Herb worked on such classic film cartoon short subjects as “Madeline,” “Mister Magoo,” and “Gerald McBoing-Boing.” Our own particular favorite is his treatment of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” for UPA.

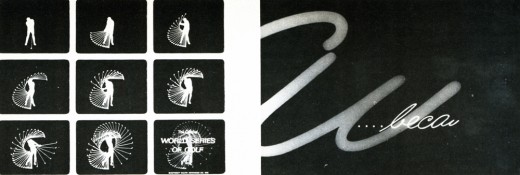

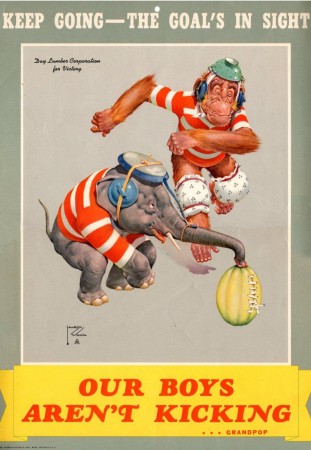

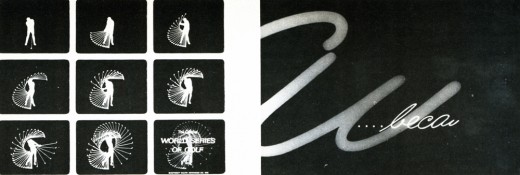

1. Graphic animation of a “strobe” like image of a golfer, made with 90 kodalith negatives

in registration. (World Series of Golf” Show opening by Goldsholl Associates.

2. The Unspoken Spoken Message: Modess “Because” (1962) Kim & Gifford Productions

Some fine animation has come out of the Midwest, too, in recent years. A key contributer from that area is Goldsholl Associates, an Illinois-based house that has brought fresh innovative graphics and experimental style to animated TV spots. In such commercials as 7-UP’s Sugar-Free “Carton Graphics” they infuse “life” into abstract dots to create a rich new imagery on screen. Colors, shapes, and textures all impart a “meaning” experi-entally to the message.

One of the more prolific of New York’s animators is Jack Zander. He began his career in 1946 at Willard Pictures doing an animated Chiclets commercial in which he animated Chiclets’ boxes like a choo-choo train to a music track taken off a 78 rpm radio transcription. In 1948, he started up the animation department at Transfilm, where he created the first animated Camel Cigarette commercials and helped develop the paper “cut-out” technique. In 1954 he and Joe Dunford opened Pelican Films and did successful commercials for over 16 years, along with Mordi Gerstein, Lars Colonius, Paul Harvey, Wayne Becher and Dino Kata-polis. During this period, Jack utilized the service of several wellknown cartoonists, including Charles Saxon for American Airlines, and later Bill Steig and George Price of “New Yorker” fame. It was also during this period that Jack did the famous Nichols and May “Jax Beer” animated series, as well as some of the early Bert and Harry Piels spots.

In 1970, Jack moved across the street and launched Zander’s Animation Parlor with his son Mark. He has created his share of “hits” in recent years, too, including the exceptionally fine Freakies campaign, beautifully animated by Preston Blair.

Another fine New York animation talent is Art Petricone who today heads up Ovation Films. In addition to his fine work for Eastern Airlines, his brilliant use of rotoscope can be seen in his work for Levi Strauss and Clairol Herbalessence.

In the area of object and figure animation and stop motion, John Gati, the Director of Special Effects, for Action Pictures in New York is unsurpassed. John has been working at his craft for 26 years and has won many awards for technique and innovation.

The art of Object and Figure Animation requires enormous craftsmanship. Basically, it resembles conventional (drawn) animation in that it follows the rule of “creating the movement” by the process of frame by frame photography. But as opposed to eel animation, which occurs on a two dimensional (acetate) surface, Object Animation is similar to live action photography taking place in a three-dimensional area.

John Gati’s creations succeed in making the product itself (the object) become the hero of the commercial, which is one of the basic tenets of good “sell” advertising. Complicated rigs and special dimensional lighting are required to make this form of animation truly work. It requires enormous intricacy to sustain the fantasy of “life” for these objects. John works with such materials as foams, wires, rubbers, vinyls, plastics, silks, clays and waxes to create the illusion of “reality.” Working in the tradition of the great artists and artisans of the past, John — like McLaren and Trnka and Geesink — has created a wondrous world of living and moving objects that reflect a “life all their own. Among his most recent successes are Fleischman’s “Egg Beaters” and Speidel’s “Faces In the Watch-bands. ”

In passing, we would also like to salute the following fine practioners of the art: Snazelle Films and Kurtz and Friends for their fine Levis efforts; Bill Melendez (Bill Melendez Productions); Hal Silvermintz (Perpetual Motion); Carlos Sanchez (IF Studios); William Littlejohn (William Littlejohn Productions); and Art Babbitt (Hanna-Barbera Commercials.)

The boundaries of animation are limitless. They defy time and space. They fuse reality with fantasy. They create new life out of old forms. Most animators believe the future will see the development of completely new and exciting techniques for the art. More use of famous illustrators and designers from the non-animation world. New developments in computer animation. More combinations of live action and animation within the same frame. More sophisticated “selling” within the framework of fantasy and humor. New breakthroughs in stop motion object animation. Fresh combinations of tape and film in animation. Unusual variations on dimensional and multi-plane animation effects.

For the most part animators strongly feel animation commercials can achieve greater results than live action, because “they can be funnier and they can be controlled absolutely” (Lee Savage); “You can get information across quicker” (Bob Godfrey);” ” “Animation makes an incredible statement real… In animation, sweeping moves are totally acceptable as opposed to the heaviness of human action (Mort Goldsholl).”

What is evident, too, is that small teams are creating the most significant new work in animation today. While the Disneys and Hanna-Barberas continue to produce a great volume of praise-worthy animation for film and TV, the breakthroughs are, for the most part, coming from the isolated artists and small creative teams working throughout the country.

And bridging the gap between these artists and the advertising agencies are producers like Harold Friedman of The Directors Circle, who fully understand the needs of both parties for creative expression, on the one hand, and sound selling messages, on the other. In the final analysis, an animated commercial to be successful must motivate the consumer to buy the product, or the service, or the idea put forth by the commercial. That is its major raison d’etre. It should be charming, to be sure, and filled with fun and fantasy — but it must ultimately sell its clients’ products in the marketplace to achieve its truest objectives.