- Back in the enlightened Eighties, Independent animation actually took note of gender in the making of animated films. In The Art of the Animated Image, An Anthology edited by Charles Solormon included an article about Women Animators in the medium. The article by Lauren Rabinovitz was part of a series published in conjunction with the Walter Lantz Conferences on Animation held June 12th thru 14th, 1987 at the American Film Institute in LA.

I reprint the article here, and I consider that, to my knowledge, it’s nice to know that all but one of these women mentioned are still making Independent films. I wonder if the record is as strong for the “Independent” male animators of the same period.

Women Animators

and

Women’s Experiences

BY LAUREN RABINOVITZ

Histories of American animation have most often located the form within the confines of the Hollywood cinema and television system. Over the seventy-five years or so of its existence, that system has seldom proven hospitable to women filmmakers, or animators, whether they were working in film or, later, in television.

Outside Hollywood, the medium of animation has flourished in the work-a-day world of education, industrial and advertising films, and in those arenas women animators have found opportunities not available in Hollywood (especially over the past twenty years). Of even greater significance, the growth of avant-garde film after World War II nurtured female, as well as male, animators, filmmakers dedicated to individual artistic expression and to the creation of new film syntaxes within an alternative economic support system.

As independent cinema became increasingly tied to college and museum institutional frameworks in the late 1960s, so too did the individual filmmakers. In that period and thereafter, they typically became identified with academic training and teaching positions, the aesthetic vocabularies of vanguard art movements, and the apparatus of an American avant-garde cinema. In the 1970s and 1980s, rising from those antecedents, feminist filmmakers and animators have participated in independent cinema networks.

However much independent cinema may be viewed as a “marginal” practice within the Hollywood hegemony, women filmmakers—and animation as a cinematic form—lie at the outskirts of those heterogeneous cinematic margins. As neither women filmmakers nor animators have extensive showcases, distribution outlets, and production monies available to them, their short works are known largely through a variety of exhibition practices: film festivals; distributors’ animation packages (often collected for and exhibited at schools and film societies); cable TV “fillers”; and individual (and often visiting) artist screenings at museums, colleges and media centers.

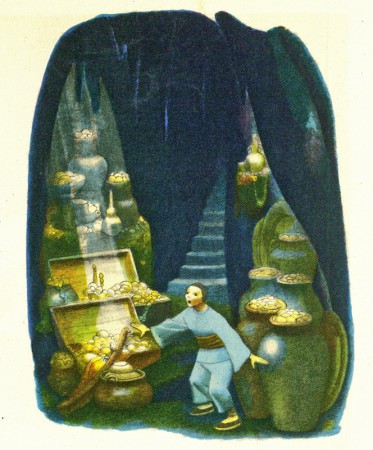

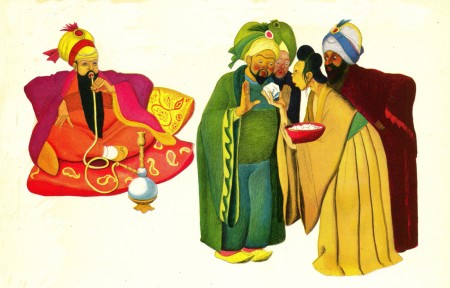

Within this somewhat limited and restricted production, distribution and exhibition network, women animators have created a broad spectrum of work, utilizing a range of animation techniques, styles, and subjects. Line animation, cut-outs, xerography, photos, computer-generated imagery, sand-on-glass, have all been used by woman animators. Some have chosen to explore formal and spatial relationships; others delve into the “serious” art of highly abstracted, non-representational animation. Some have relayed children’s stories and folktales, personal experiences and feelings; others have created humorous narratives and political satires. Many have chosen to construct animated tales that comment on the artistic process itself. There is no “women’s animation” any more than there is one unique form of women’s film or video.

Nonetheless, just as male filmmakers have frequently exposed intimate, often sexual experiences from a subjective point-of-view, women animators tend to explore women’s experiences from an equally subjective perspective. Such subject matter takes on a dual political dimension—in the increased visibility and expression of gender identities and experiences, and in the recognition of the systematic repression of women’s subjective experiences within the Hollywood cinema. A significant number of contemporary women animators rely on cartoon animation— figuration in short narratives—as a means of recasting their relationship to the ideology of representational cartoons.

There is a long list of recent films by women animators that address women’s experiences in this fashion. They run the gamut, from Tanya Weinberger‘s tiny naked woman who carouses on and then arouses a sleeping giant in Gulliver Comes to Lilliput (1983) to Suzan Pitt‘s Asparagus (1978), an elaborate eel-animated psychodrama that intertwines a woman artist’s creative process with metaphors of sexual activity.

Christine Panushka‘s The Sum of Them (1983), line portraits set against a familiar collage of sounds, depicts many women as an absorbing poem of humanity. In Another Great Day (1980), Jo Bonney and Rugh Peyser dramatize the important inter-relationships among popular cultural forms, fantasies, and women’s labor through a housewife who moves freely between the cartoonesque world of her chaotic household and the photographic world of television soap opera and romance photo-novels. Women have also collaborated to celebrate collectively their experiences as’ women who are not always “solitary” animators. Lisze Bechtold, Lesley Keen, and Candy Kugel, My Film, My Film, My Film (1983); Caroline Leaf and Veronica Soul, Interview (1979).

Some artists portray an autobiographical female subject notable for her physical metamorphoses, which approaches self-induced schizophrenia. In turn, this state of fluid change can often provide a positive catharsis. For example, Karen Aqua‘s Vis-a-Vis (1983) turns the artist/character into two connected halves of one person—the animator at her storyboard and the woman gazing out the window. When the halves split, the artist animates kaleidoscopic images while the woman passes through richly colored sea and mountains. When the woman returns to the artist, she empties radiant color into the drawings.

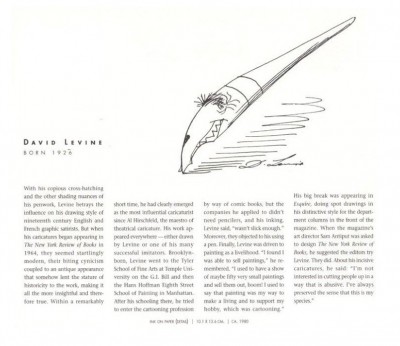

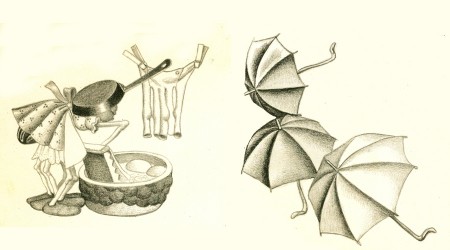

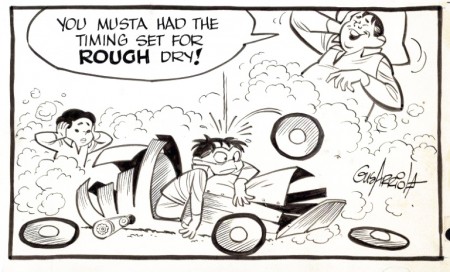

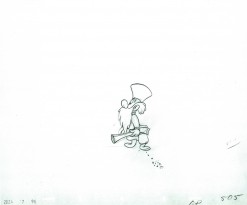

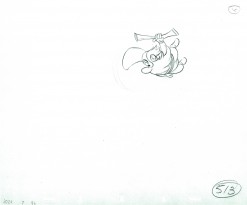

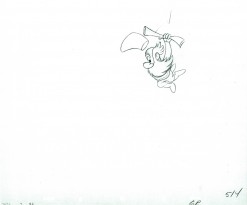

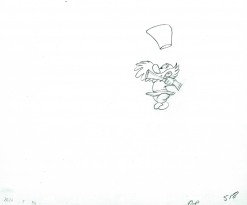

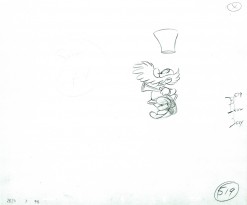

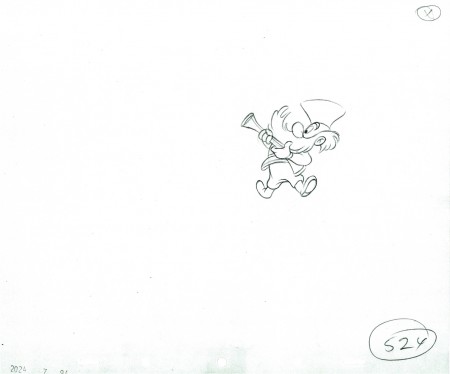

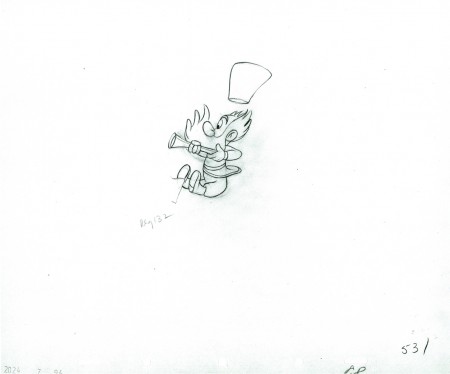

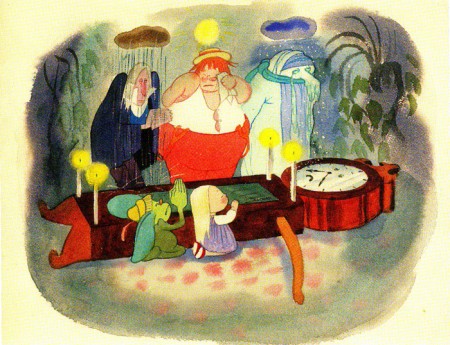

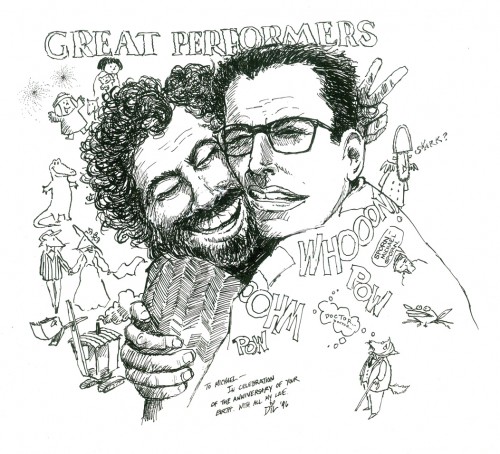

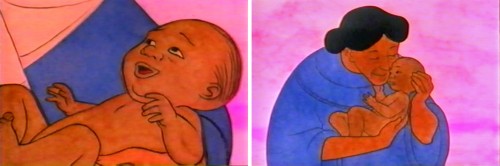

Kathy Rose’s Pencil Booklings (1978)

Kathy Rose also plays with the magical transformations of an animator character. Mirror People (1974) and The Doodlers (1975) both rely upon the protagonist’s constantly evolving physical shapes in an eerie, surrealistic world. In Pencil Booklings (1978), the artist/character (who resembles Rose) is represented more naturalistically through rotoscoping. Within the narrative she is pulled into the world of her imaginative creation and eventually back out of it, her identity assured by her exploration of the creative process itself.

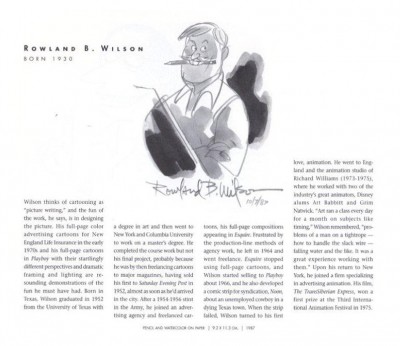

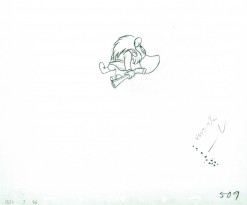

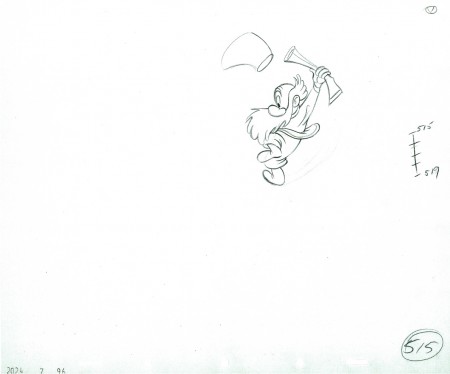

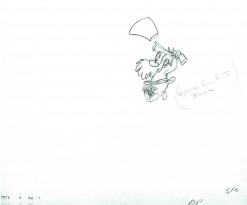

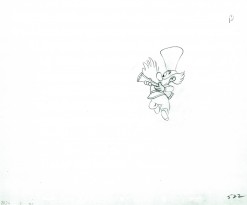

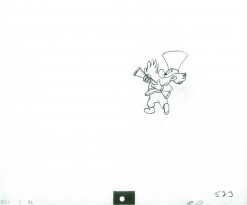

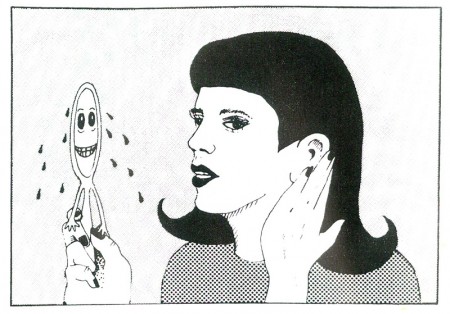

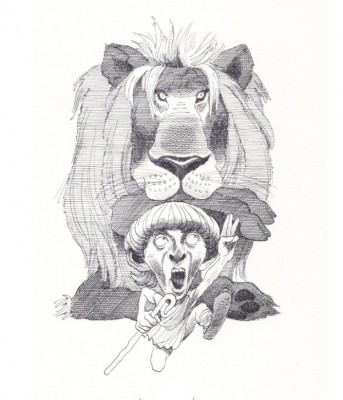

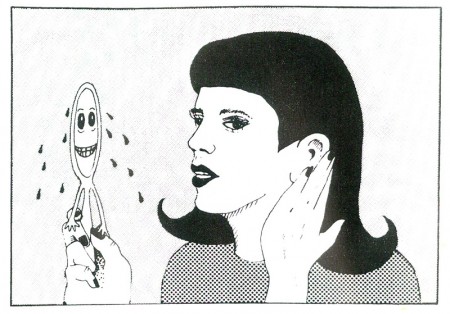

Joanna Priestley‘s Voices (1985:) also relies upon the artist’s physical presence as well as her v ice to comment on her self-image. As a likeness of the filmmaker addresses an anthropomorphic (and smart-alecky) mirror, she describes first her bodily-related fears of aging, gaining weight, and wrinkles. As she succumbs to her preoccupation with fear itself, she gives vent to increasingly cataclysmic horrors that are visually portrayed— things that go bump in the night, monsters of the id, nuclear holocaust. The background prattle provides a counterpoint to the character’s self-absorbed fears creating a tongue-in-cheek commentary that suggests women’s fears about themselves are a culturally induced neurotic obsessiveness.

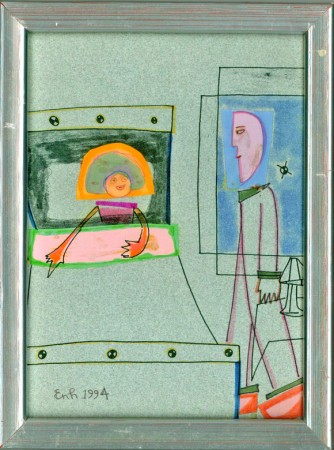

Joanna Priestly’s Voices (1985)

It is important to note that these artists depart from the traditional Hollywood use of sound, the acoustical enhancement of nature. Although the cartoon world may always be seen as inherently fantastic, the animation studio’s use of sound helped reinforce the notion of a spatial and physical world. These animators employ layers of sound effects and music to destabilize the spectator and to stress the fantastic itself.

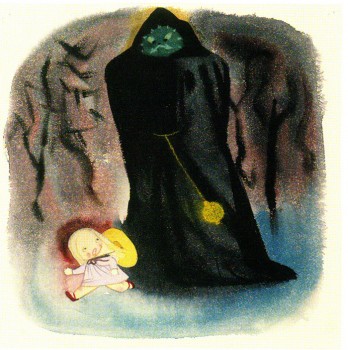

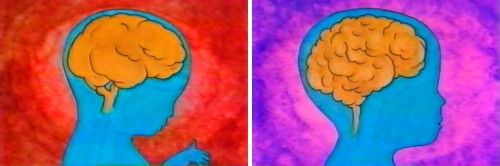

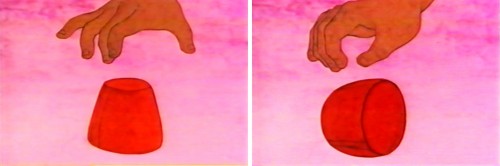

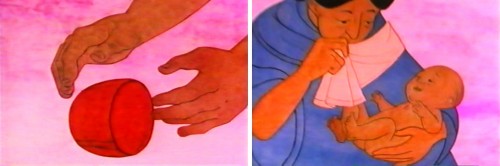

Emily Hubley, the daughter of animators John and Faith Hubley, carries the metamo-phosing, autobiographic subject to new intensities. In Delivery Man (1982), she presents a simply drawn, ever-changing abstract self in an equally volatile, abstracted world. Less the object of whimsical artistic introspection than the subject of her fearful dreams relived, the constant visual metamorphosis supports a remembered vision of personal traumas. The woman’s personal narrative of five key dreams involving her birth, her mother’s surgery, and her father’s death during surgery visualize the crisis of familial relationships, development and sexual identity that comprise the subjects of many patients’ transactional analysis.

Kathy Rose has extended the woman animator’s autobiographic involvement to a redefinition of the medium itself. Her Primitive Movers (1982) is a 30-minute piece that combines animation and Rose’s dance performance in front of the moving images. The animation is a constantly moving, colorful backdrop of lifesized dancers who evoke series of art styles—from Egyptian to Cubist to Art Deco. Their relentlessly rhythmic, angular movements provide not so much a chorus line for Rose’s sharply expressive movements but a fluid commentary on changing spatial relations, perspective, and Rose’s intertwining of 2 and 3 dimensions, as well as her bodily interaction with them.

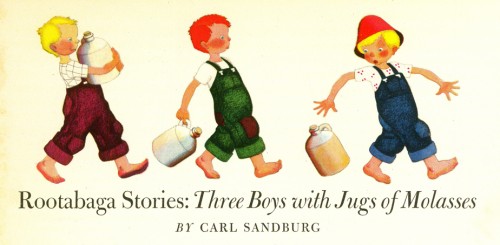

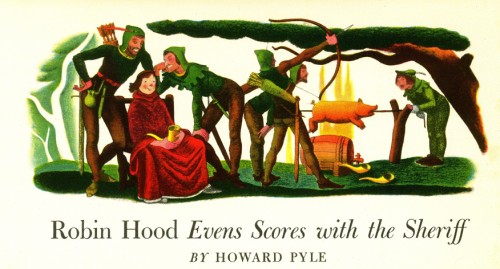

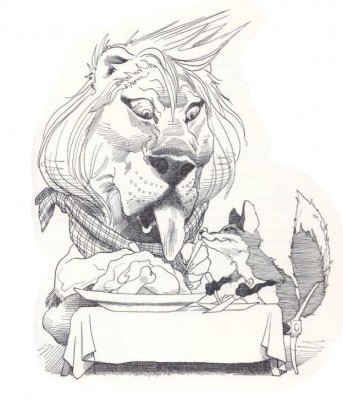

In this regard, several women animators connect their work to the history of art in ways that allow them to reconstitute woman’s place—no longer the object of male desire, but as the controlling subject. Maureen Selwood‘s Odalisque (1981) is, perhaps, the best example. In a humorous inversion of the history of western painting, Selwood portrays her odalisque as the subject who imagines and controls the flow of images. This female is no longer the prisoner of other artists.

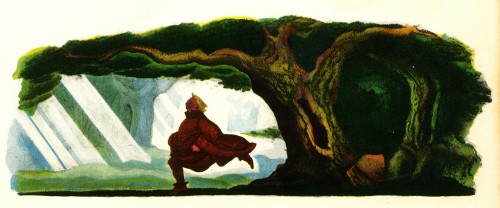

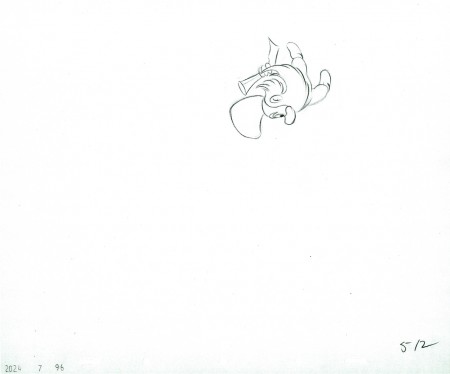

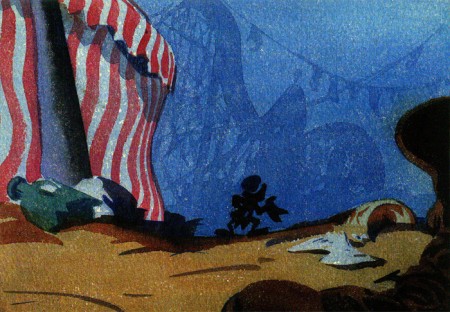

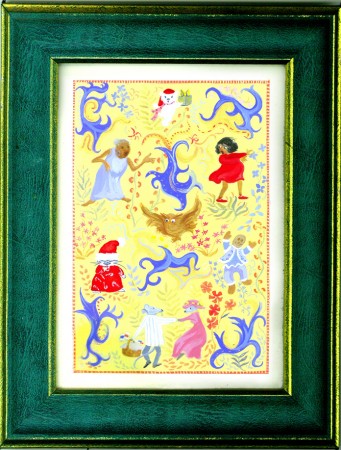

Maureen Selwood’s Odalisque (1981)

Selwood calls attention to a more naturalistic figuration as the basis for a realism regarding women in Western art. By juxtaposing two styles in a jarring fashion, she poises fluid, graceful motion associated with the feminine against the disintegration and evaporation of form associated with the cartoon world. Made with the aid of romance and adventure—as a cafe artist and an opera singer—in these dreams, she deflates as male fantasies the romantic conventions usually associated with these constructs. In each sequence, she escapes the conventional confines of the fantasy that would relegate Woman to passivity or death and flows back to her living room, her visually nurturant world.

Whether there is an inherently feminine language in these works as well as in women’s writing, visual arts, and other expressive arts has been a topic of much feminist discussion in the 1970s and 1980s. Some critics maintain that even acknowledging the existence of feminine language does not insure that such “inscriptions of women’s voices” will be necessarily heard by all audiences. Female filmmakers frequently rely upon existing codes and conventions no matter how much they are filtered through their own vocabulary. In addition, their audiences may choose to interpret the films within the confines of already established canons, an act sometimes amplified by the films’ marketing and critical reviews.

What is at stake here is not the discovery of a feminine or feminist aesthetic running through women’s animated films, but the ways in which contemporary animators collectively construct feminist experience. They rely upon devices usually associated with expressive animation—physical metamorphosis, strongly-defined character personalities, and dream-like fantasy logic. But they represent these processes by defining women as their subjects, presenting specifically female sexual and non-sexual fantasies, and imagining self-identity and fears through one’s physical changes and fluidity as well as through controlling the environment outside oneself.