Books &Commentary &Disney &Story & Storyboards 02 Aug 2010 10:08 pm

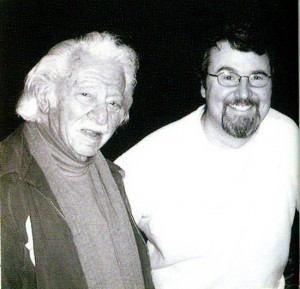

Joe and Joe

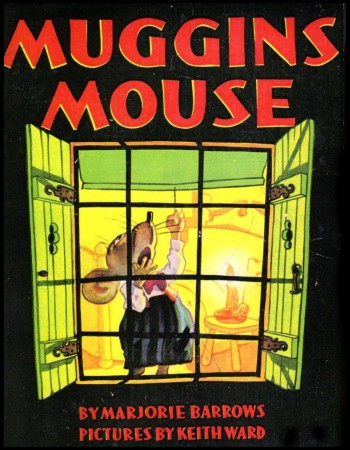

- Today is the day that John Canemaker‘s book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft officially hits the stores. I urge you to take a look and go for it. The book is great.

- It was about nine months ago that John Canemaker let me read the galleys of his new book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft. I’d been aware of the book for a couple of years now, and whenever I’d heard John talk about it I wondered how the two guys fit in together to make a book. When I was handed the galleys, I moved slowly ahead with some trepidition.

- It was about nine months ago that John Canemaker let me read the galleys of his new book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant and Joe Ranft. I’d been aware of the book for a couple of years now, and whenever I’d heard John talk about it I wondered how the two guys fit in together to make a book. When I was handed the galleys, I moved slowly ahead with some trepidition.

I basically knew who the two Joes were from my reading and my NY attempts to keep up with the Hollywood system. Joe Grant was an old timer who’d dominated the Disney modelling department (the only time there was a department exclusively for model sheets), and he’d come back to act as one of the wizened artists helping to shape the new “Renaissance” in the animation community. Joe Ranft was one of the key CalArts guys who’d gone through the Disney system on his way to Pixar where he helped to shape that studio. There’s no doubt he was key to Toy Story, A Bugs Life and Monsters Inc.

What connection would John Canemaker have for tying these two together? Would that connection be enough to fill a book?

Of course, all such conjecture was stupid on my part. The book, as it turned out, is one of John Canemaker‘s finest, and that’s saying a lot. John, after all, is one of the best of our animation historians. His material is well researched, his facts are accurate, and his information is always pertinent and absorbing. He is also a good writer. He tells a story and reveals his information as any good writer would. There’s a solid construction to all of his books, and he lets you into the book in a comfortably relaxed way so that you’re absorbing the story and facts all together, and you are pulled into the book. This is the greatness of Two Guys Named Joe.

As for the connection, John explains that well. Not only, of course, within the book, but he had this succinct statement to make in an interview with Amid Amidi: “I saw the possibility of an overview of the history of storytelling at Disney and Pixar through a very human story of two artists straddling the 20th and 21st centuries.” And that’s exactly what John uses the book to do. He wants to really upchuck the earth of the story departments of both Pixar and Disney, and he does a good job of it.

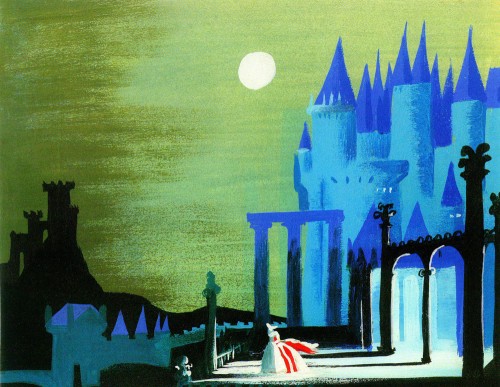

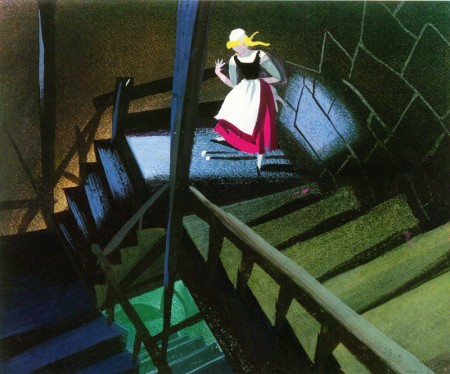

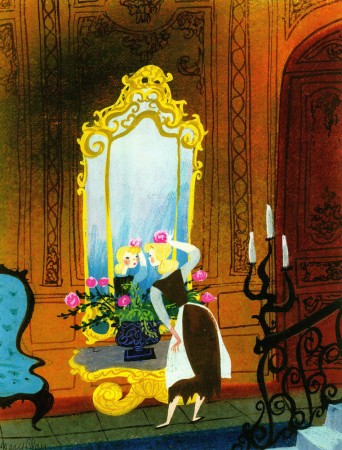

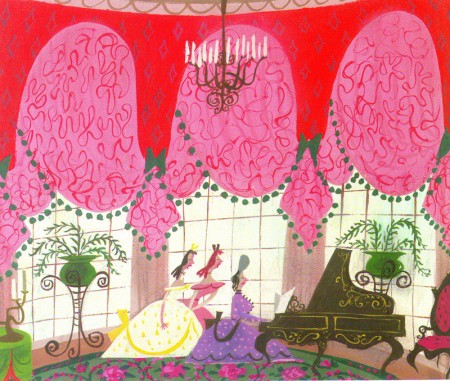

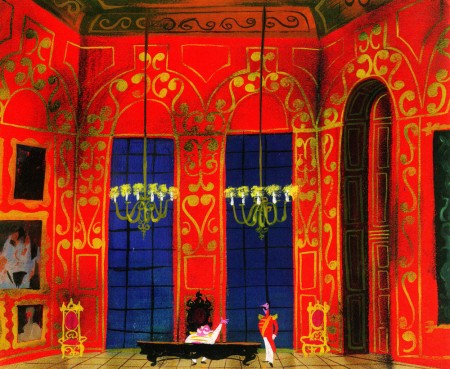

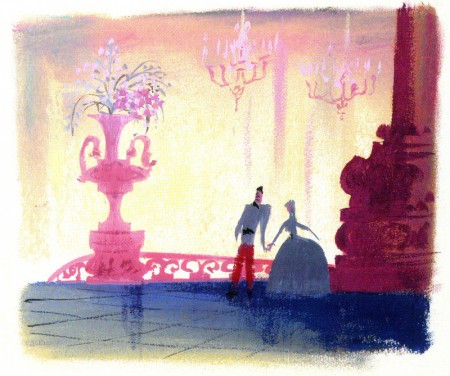

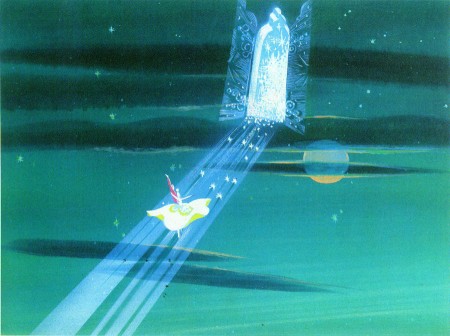

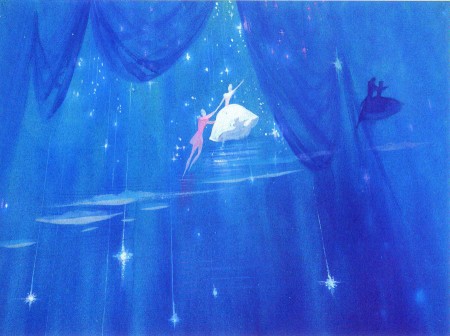

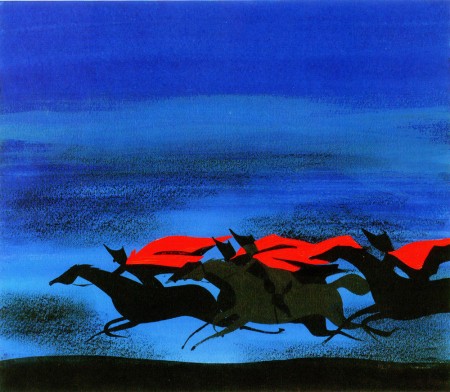

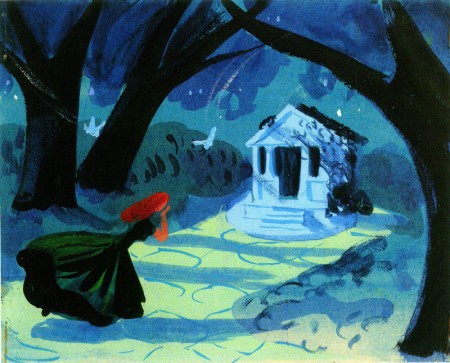

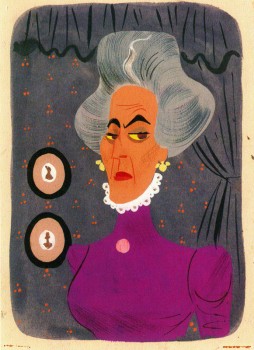

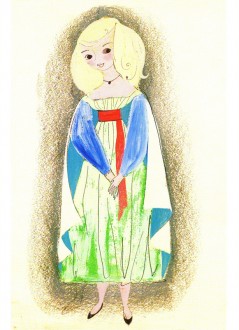

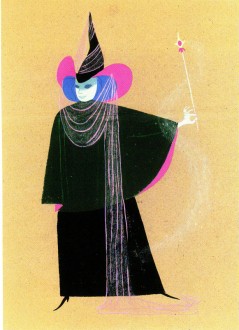

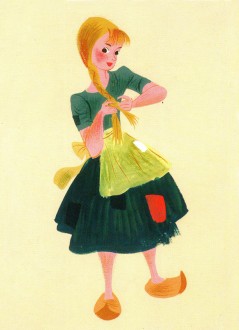

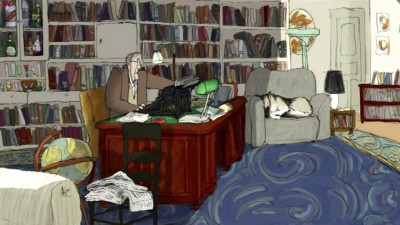

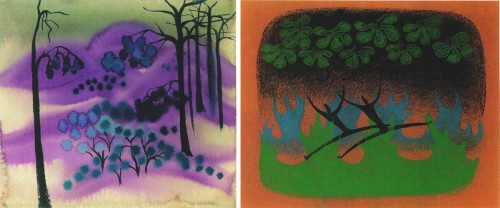

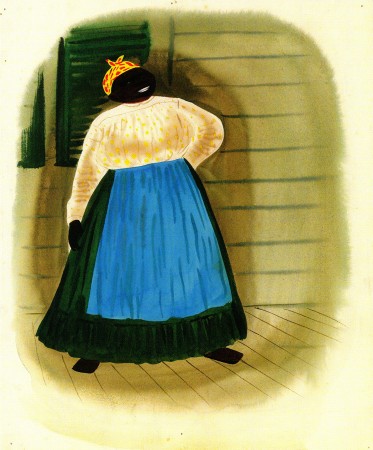

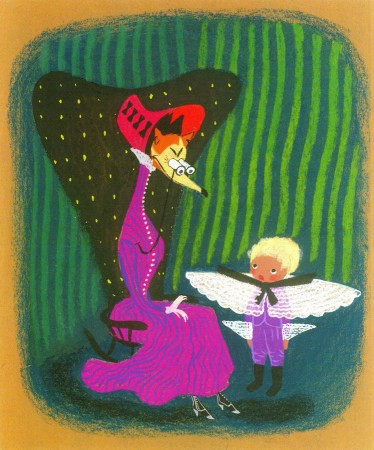

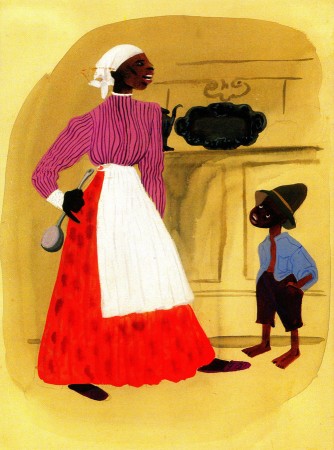

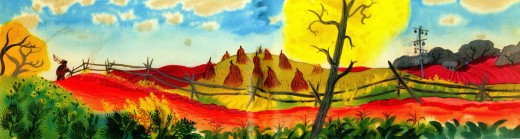

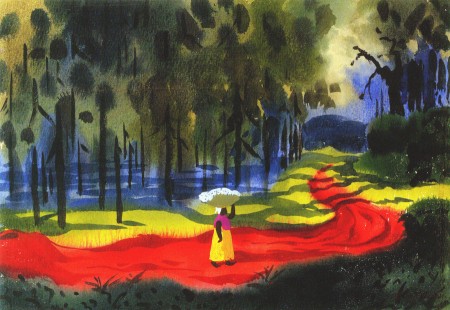

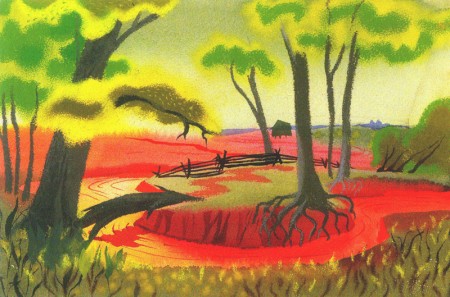

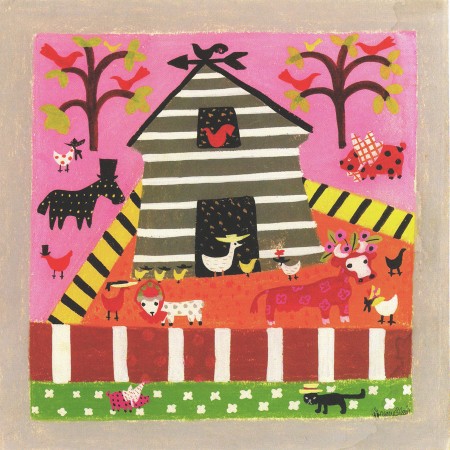

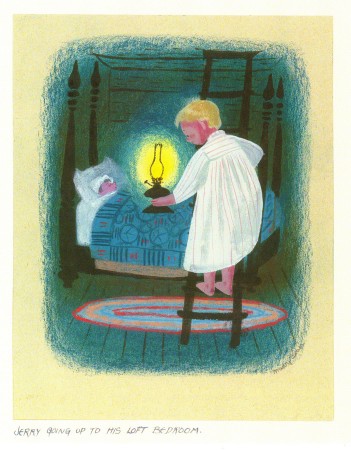

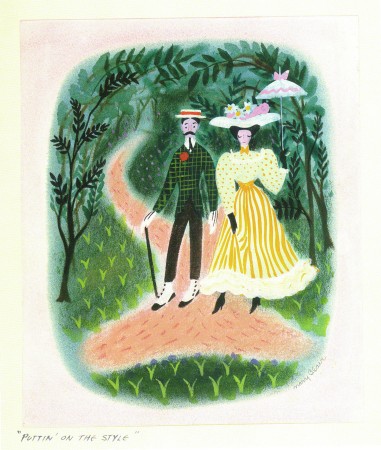

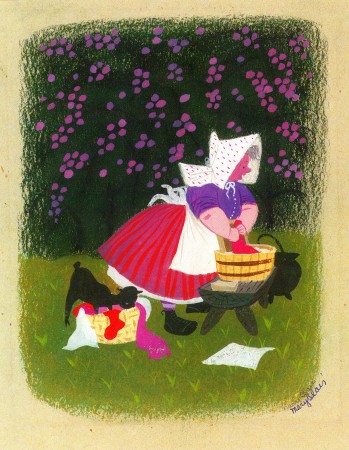

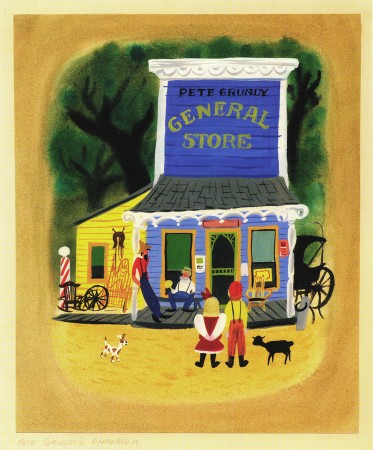

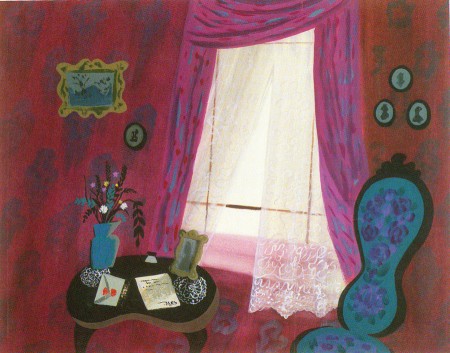

I’ve now read the book twice. Once in galley form, once in final book form. The book is a rich-looking item full of the finest artwork from storyboards, printed material and developmental art. It’s a gorgeous book.

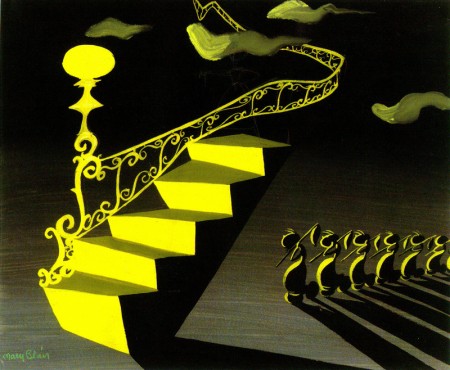

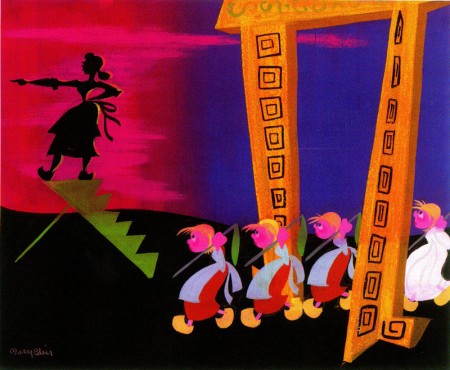

However, the real gold is in some of the writing and treasured bits that John has dug up to support his material. Here, for example is a small piece about Alice In Wonderland’s story development:

A March 15, 1939, story conference transcript reveals Walt’s frustration with the project:

A March 15, 1939, story conference transcript reveals Walt’s frustration with the project:WALT: (To Joe) Have you been through A//ce in Wonderland lately?

JOE: No. I’ve been through the script though. I think there are some pretty good situations in this.

WALT: Yes, and some, too, that are not so good.

JOE: I like the stuff on the disappearing cat—swell possibilities in that.

WALT: Yes. Let’s see. What are the good situations?

JOE: The tea party stuff is good.

WALT: Yes, the tea party is to me the best. . . You

know, I think we’re missing a hell of a lot in the stuff that is our medium. . . everything isn’t dialogue. Talk, dialogue business that depends on dialogue, hinges on dialogue.

Disney then tore into an unfortunate writer named Dana Coty.

WALT: I’m saying that to you because I think maybe

you’re the one that’s responsible for a lot of silly business that has no basis on anything funny.

DANA: Well, in the duchess’s house, I wrote that very loosely to begin with, Walt.

WALT: I don’t give a damn how you wrote it. It’s what we’re driving at. If it hasn’t got a basis for something funny, don’t write it! There’s no use writing the thing and then alibi-ing for it afterwards. It just throws us off the, track. Don’t just write anything to fill up some pages. We had the same criticism, the last time we were together.

John uses this anecdote to not only say something about Disney, himself, but the way he communicated with Grant and the hostility he might display for others. He did not mince words or waste time where he thought it was wasted. They were trying to solve the problms they saw in Alice In Wonderland, but we learn that Grant, Huemer and others felt that Disney was the problem. They felt he didn’t quite understand the Victorian humor of the original and tried to gag it all up. It’s just one wonderful excerpt dug deep in the book.

Another gem of a sequence involves Joe Ranft. It’s the point just when the Pixar artists are trying to sell Toy Story to the Execs at Disney. They’re doing everything in their power to make the film story good while placating the Disney people, and they’re having a hard time of it.

- Disney insisted the production move to Los Angeles so the studio could oversee things. “And give us more notes,” Ranft lamented.

Lasseter, whose “heart was broken,” begged for a two-week reprieve to turn things around. After obtaining Disney’s skeptical permission, Lasseter, Ranft, Docter, and Stanton resolved to “make the movie we want to make!”

. . .

The process included writing, gathering more material, constant meetings, weeding out, refocusing, and . . . more meetings. “Two or five heads are better than one,” Ranft believed. “If you can work together without killing each other, you an accomplish a lot.”

Going forward, Pixar gladly accepted notes from Disney and welcomed participating in brainstorming sessions with their artists. “But,” Ranft said, “we’d go away and really think about [the notes]. A lot of times we’d go, ‘No. Here’s the real problem!’ And it was even deeper than the notes. ‘And here’s how we’re going to fix it.’”

Regarding the creative process, Ranft once said, “It’s a challenge. The final product is the goal you’re searching for. [Your little sequence is] gonna get smashed, trashed. It’s gonna come apart for the good of the final film . . . it’s a paradox. You’ve got to put yourself into it, and then you’ve got to take yourself out of it. Be objective and not be hurt.”

And that’s the point of the two guys. They understood the value of the story and the center of the films they worked on and over. Nothing mattered, including personal insult, as long as the story came out right. They were film artists and knew how to get what they needed to complete their goals.

My personal preference is to want to know more about the old timer and to learn more about the golden age. However, it’s totally my bias, and the proof of this book’s success is that I was completely absorbed by all that was written about both men.

This is more than a good book. Anyone in love with animation should own a copy and read it carefully. There’s a lot there, and it’s all good. It’s stunningly designed with beautiful animation art treasures well displayed.

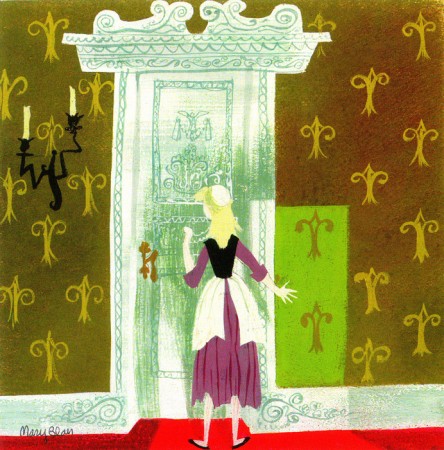

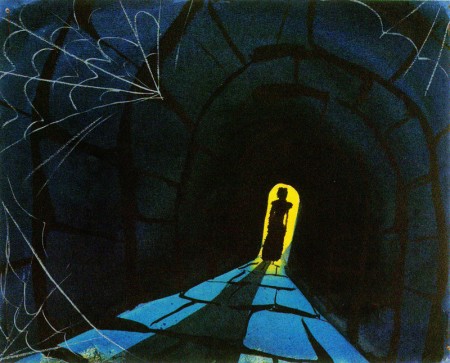

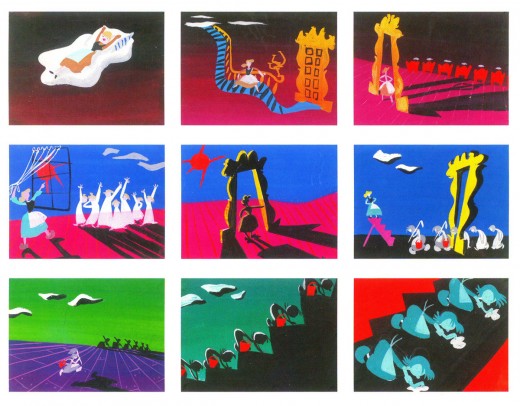

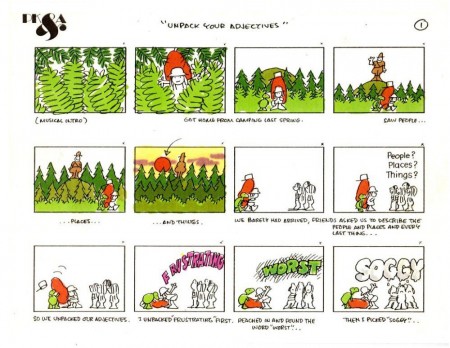

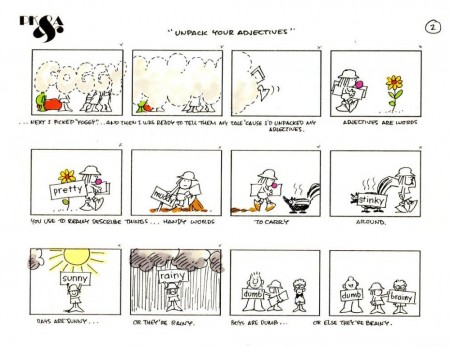

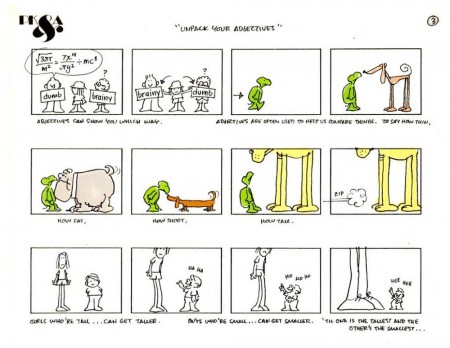

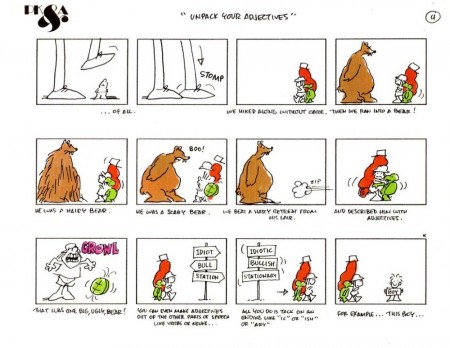

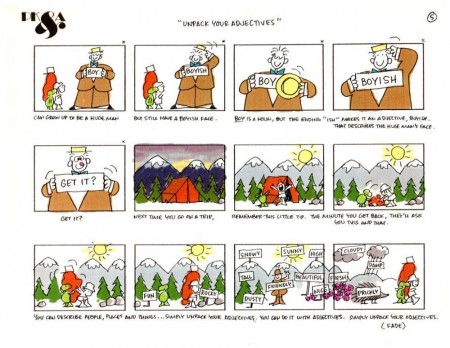

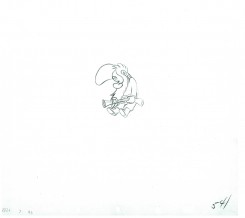

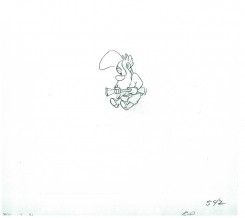

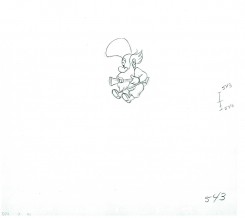

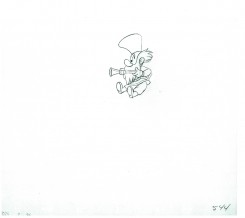

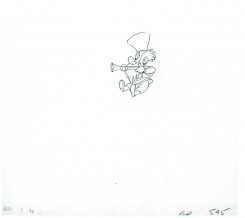

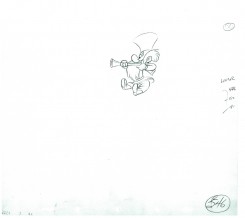

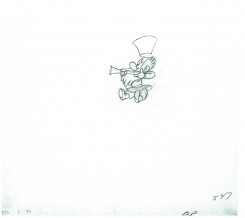

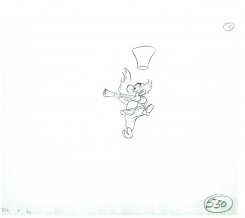

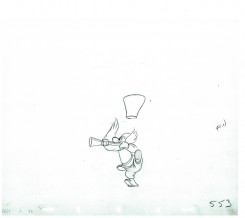

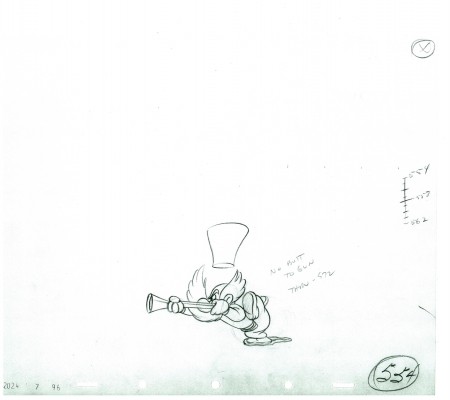

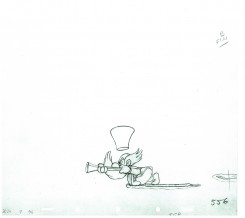

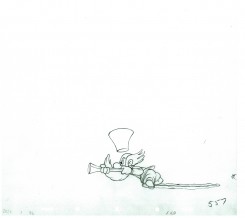

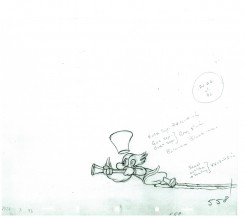

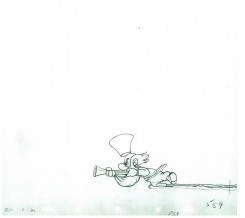

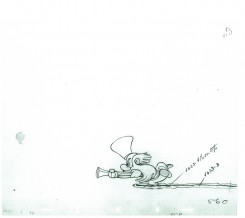

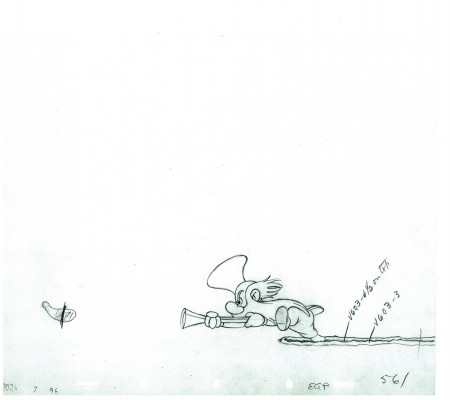

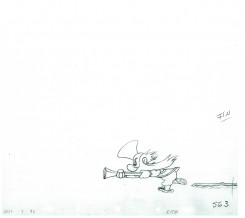

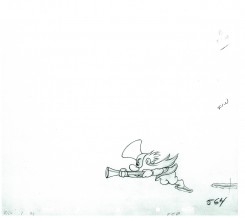

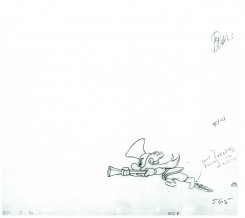

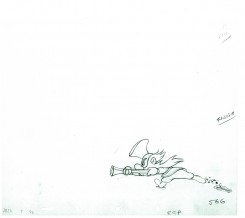

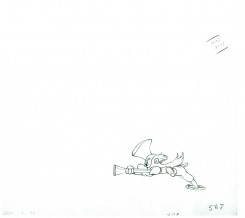

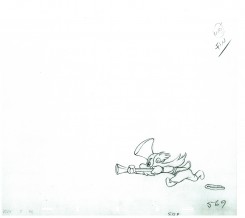

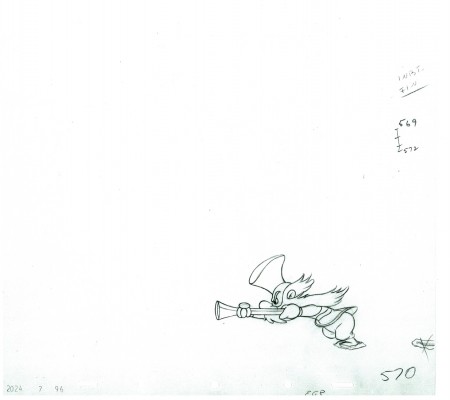

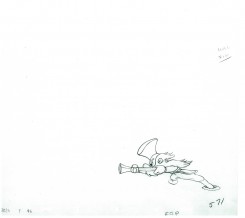

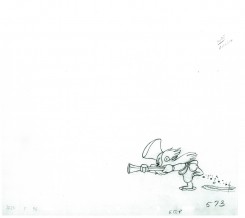

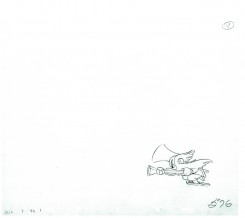

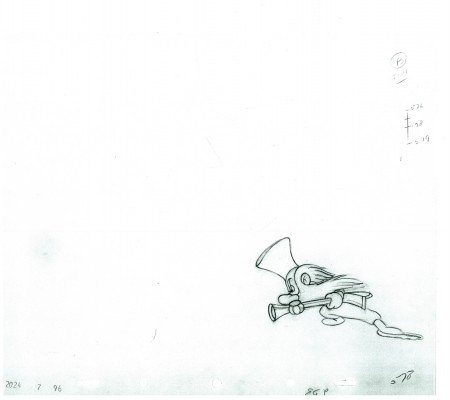

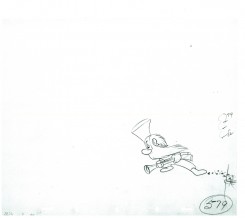

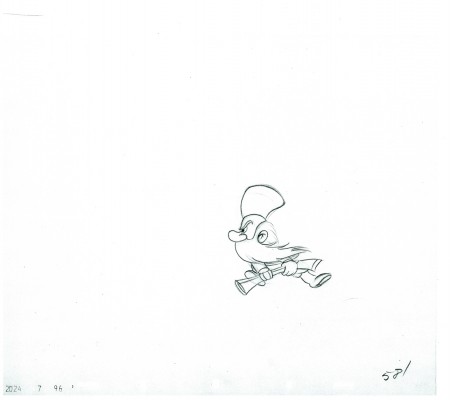

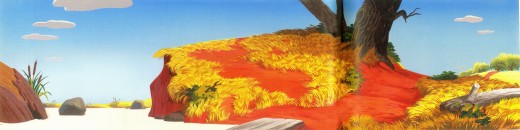

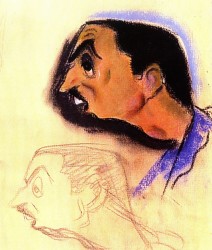

A telling board by Ranft.

________________

Amid Amidi offers an excellent interview with John Canemaker on the subjects of the book at his Cartoon Brew site. I recommend you all read it.

There’s also a video promo you can catch on YouTube if you’re more visually oriented.