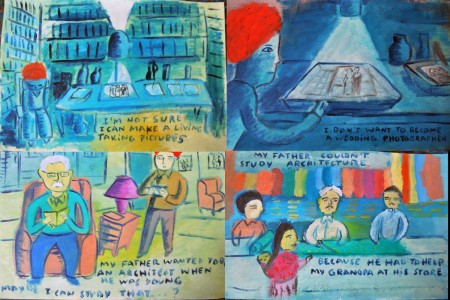

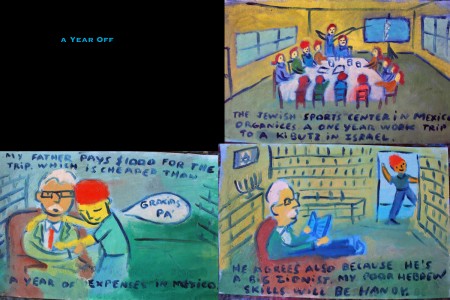

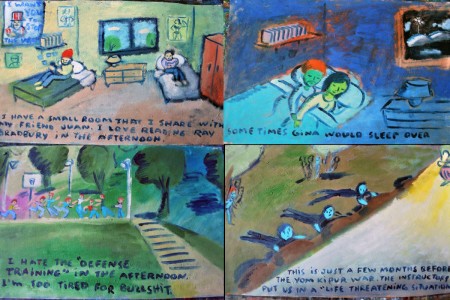

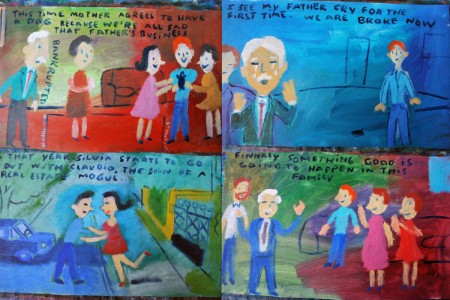

Animation &Articles on Animation &Disney 22 Oct 2010 07:46 am

Oskar Fischinger at Disney

The following article appeared in the 1977 Anmation Issue of MILLIMETER MAGAZINE as edited by John Canemaker. (Some of those commercial magazines were just excellent back then, and we never seemed to notice or properly appreciate them.)

or, Oskar in the Mousetrap

by William Moritz

Oskar Fischinger at work at the Walt Disney Studio in 1939

Courtesy of Mrs. Elfriede Fischinger, all rights reserved

The official Disney account of the origin and making of FANTASIA has been told many times — from the early press releases, programs, and Feild’s wide-eyed, idolatrous book from 1942, THE ART OF WALT DISNEY (all united by the “official studio policy”/ mannerism of discussing primarily Walt Disney himself as if he had conceived and designed the films almost single-handedly), down to the more reasonable, carefully-researched materials published recently, such as the article by Disney archivist David R. Smith for MILLIMETER’S 1976 animation issue, and Bob Thomas’ new biography, WALT DISNEY, AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL.

I have already given an outline of another side to this story in my bio-filmo-graphy of Oskar Fischinger (FILM CULTURE 58-59-60-, 1974, pp. 61-65), but Fischinger’s tale bears re-telling since clearly a full understanding of the matter lies in discovering all that went on behind the scenes and in Fischinger’s heart-of-hearts.

Oskar Fischinger, who was a year older than Walt Disney, devoted his major energies throughout his life to abstract animation. In the early Twenties, while the Disney brothers assembled Ub Iwerks and a remarkable collection of talents to form an animation studio for production of Alice and Oswald cartoons, Fischinger, working on his own, struggled with radical experiments in non-objective imagery — from sliced wax to multiple-projector light shows. Even before sound film became available, Fischinger synchronized his abstract films to phonograph records and live musical accompaniments, because he found that the analogy with music (i.e., abstract noise well-developed and widely-accepted non-objective art form) helped audiences to grasp and accept the nature and meaning of his “universal”, absolute imagery. Oskar never meant to illustrate music, and often screened his “sound” films silently for already sympathetic audiences.

At the same time Iwerks/Disney’s Mickey Mouse and SILLY SYMPHONIES (and clever mass-marketing techniques) began to gain world-wide acclaim for the Disney Studios, Fischinger also enjoyed a moderate international renown as well, with his black-and-white STUDIES playing as novelty shorts with features from Uruguay to Japan. And while Disney began to win Academy Awards for his shorts, Fischinger also won grand prizes at film festivals in Brussels and Venice.

By 1935, Fischinger had made at least 35 abstract animated shorts, and stated as his New Year’s wish in the Berlin trade paper FILM KURIER that he wanted most to create an animated feature composed entirely of non-objective imagery and diverse music (he had used jazz, toyed with experimental electronic music and his own synthetic drawn soundtracks as well as classical music).

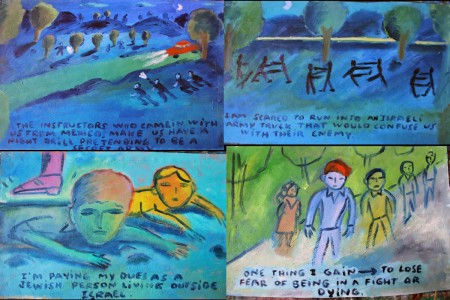

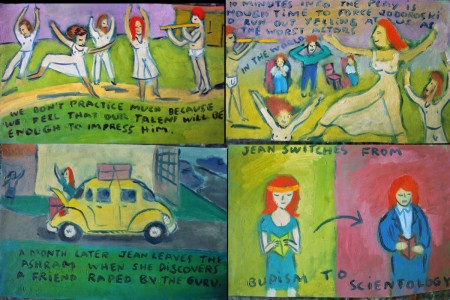

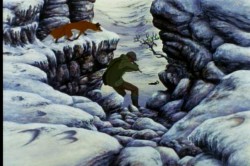

A scene from Walt Disney’s FANTASIA (1940)

Unfortunately for Fischinger, political events militated against him for much of his life, but he still produced a body of work that plays increasingly in theatres and museums as several full-evening programs.

The Nazi government had banned abstract art as degenerate, and was officially outraged that Fischinger’s COMPOSITION IN BLUE won festival prizes. Oskar in turn happily accepted a contract with Paramount and sailed for Hollywood in February, 1936, never to return to Germany. Unfortunately he spoke no English and encountered tremendous, frustrating difficulties in his early studio jobs. He assumed Paramount wanted him to pursue the style of his prize-winning COMPOSITION IN BLUE, but instead they wanted more representation and cuter work like his Muratti cigarette commercials. After he had completely painted and photographed a color abstract sequence (later called ALLEGRETTO), the director Mitchell Leisen insisted the piece be re-done in black-and-white with representational images of musical instruments and other pop trick effects overlayed. The resulting studio version disgusted Fischinger and he quit Paramount only half-a-year after he started there.

His second American film, AN OPTICAL POEM, made for MGM under William Dieterle’s aegis, proved one of Oskar’s finest works, and though not exactly a box-office sensation, played prestige bookings with first-run features, and was mentioned by one critic as a likely Oscar nominee (which caused Fischinger to quip, “Why bother giving me Oscar? I am Oskar!”).

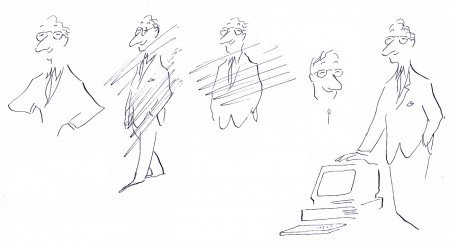

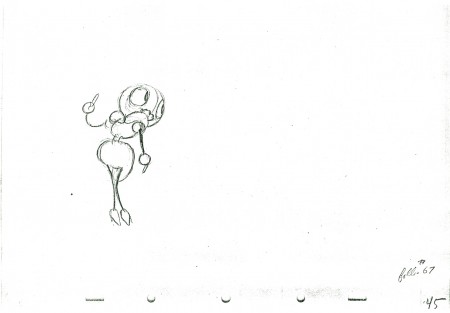

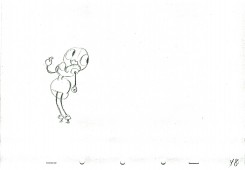

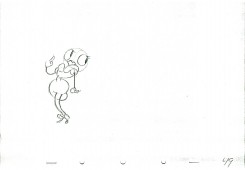

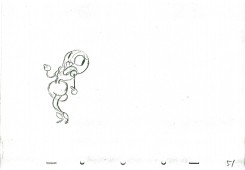

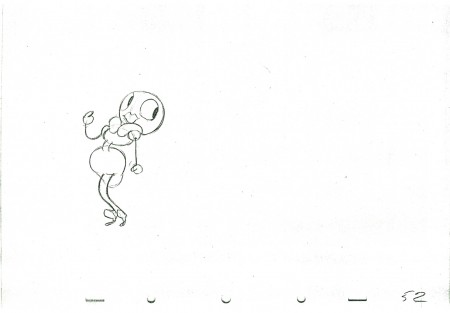

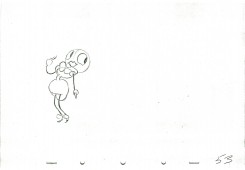

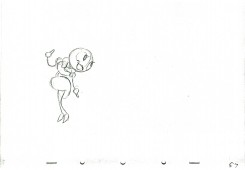

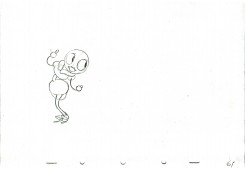

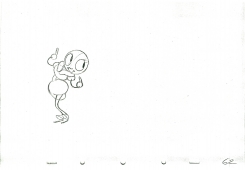

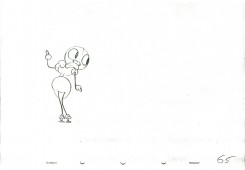

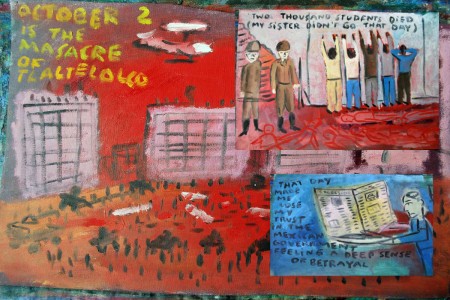

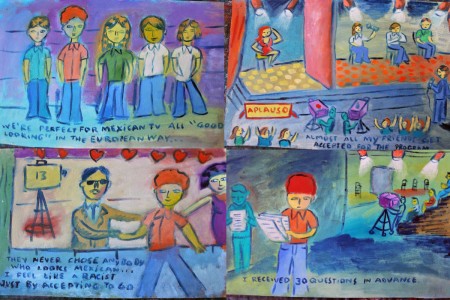

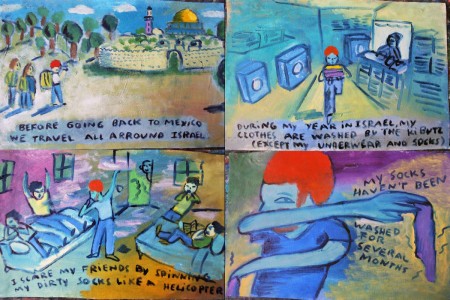

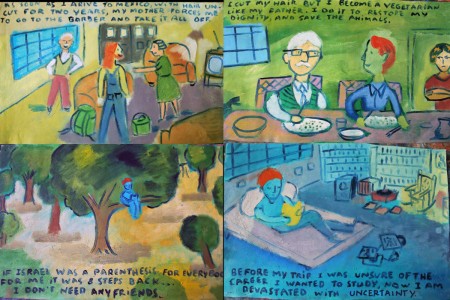

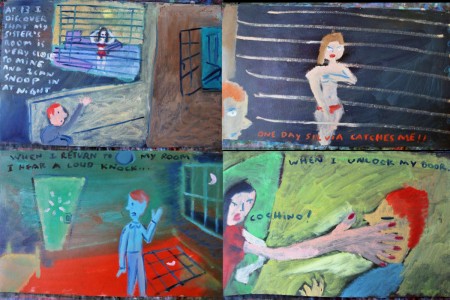

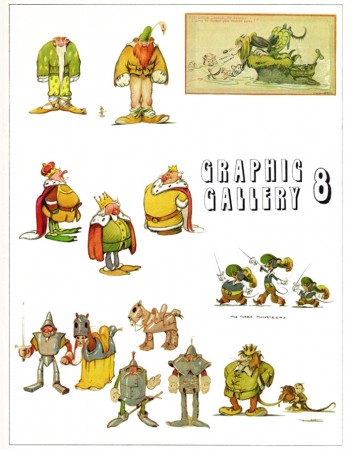

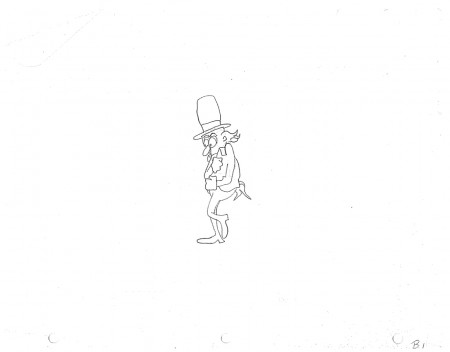

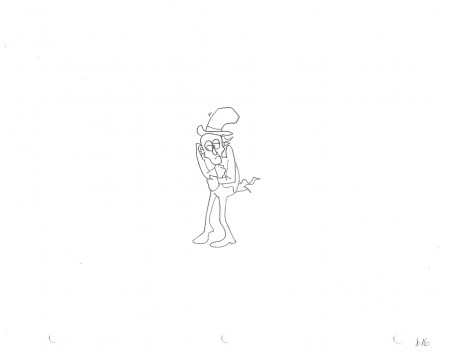

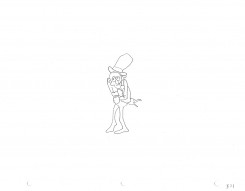

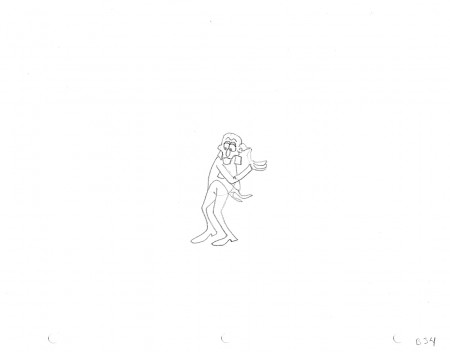

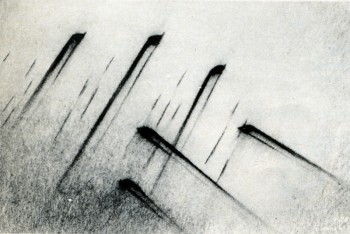

A Fischinger pencil sketch (with numerical

motion-phase breakdowns) for “Toccata and

Fugue” section of Disney’s FANTASIA.

After his MGM option was not picked up, Fischinger drove to Detroit and New York seeking backing for a feature-length animated film based on Dvorak’s “NEW WORLD” SYMPHONY, which he hoped to be able to present at the World’s Fair. Although this project never materialized, Oskar dallied in New York because he discovered a new ambiance there: unlike Hollywood, he was treated as a major artist in New York, invited to screen his films and exhibit paintings, dine with leading filmmakers, critics and painters, spend weekends at the country estate of Guggenheim Foundation curator Hilla Rebay. He returned to Hollywood only when his agent cabled that he had a job for him at Disney.

What a rude shock Fischinger received upon his return! Already in Berlin, Oskar had been attracted to Leopold Stokow-ski’s grand orchestral arrangements of Bach and had tried to get music rights to some of his pieces. When Fischinger found that Stokowski was his co-worker at Paramount, he once again proposed a series of shorts or an anthology feature. Stokowski was initially quite receptive and wrote Fischinger (October 9, 1936, on Paramount stationery), “I should be very happy if we could work together — you doing what is seen, I doing what is heard.” And he received from Fischinger such elaborate ideas as (November 15, 1936, in German):

“If you are here at Christmas, I’d like to make a full-length shot of you in such a way that the visual part of the film could begin with you conducting the first few bars of the music, and then the eyes of the viewer would glide with a movement of your hands off into endless space where the rest of the visuals would unfold. ”

Nevertheless, after several conferences, Stokowski decided that the project would be too expensive and complex for Oskar to animate alone, and suggested that they seek support from a major studio, perhaps Disney. Fischinger held little hope for satisfactory help from Hollywood, especially after his experiences, and furthermore he knew from gossip that Disney, despite his successes, was under severe strain, borrowed and mortgaged to the hilt. And Oskar’s worst fears were seemingly confirmed when he returned to Hollywood in November, 1938, to find that while Stokowski was being honored as Disney’s major collaborator on “The Concert Feature”, Fischinger was being hired for $60-per-week (Paramount had paid him $250) as a “Motion picture cartoon effects animator”.

Fischinger accepted the job since work was scarce and he had four children to support, but for him the Disney episode proved a nightmare which so angered him that he conspicuously avoided talking about it in later years. Only once did he write a note on his Disney adventure (in a letter to a friend), and it expressed well his chagrin:

“I worked on this film for nine months; then through some “behind the back” talks and intrigue (something very big at the Disney Studios) I was demoted to an entirely different department, and three months later I left Disney again, agreeing to call off the contract. The film “Toccata and Fugue by Bach” is really not my work, though my work may be present at some points; rather it is the most inartistic product of a factory. Many people worked on it, and whenever I put out an idea or suggestion for this film, it was immediately cut to pieces and killed, or often it took two, three or more months until a suggestion took hold in the minds of some people connected with it who had their say. One thing I definitely found out: that no true work of art can be made with that procedure used in the Disney Studio.”

At first, Fischinger threw himself whole-heartedly and good-naturedly into the project. He gave prints of his films to be screened weekly for the entire Disney staff, so his influence was pervasive (spilling over onto other films like DUMBO, the South American films, and PINOCCHIO, for which Oskar actually animated the magic wand of the Blue Fairy). In the mimeographed transcript of the story meeting for February 28, 1939, Walt Disney says (p. 1): “Everything that has been done in the past on this kind of stuff has been cubes, and different shapes moving around to the music. It has been fascinating. From the experience we have had here with our crowd — they went crazy about it. If we can go a little further here and get some clever designs, the thing will be a great hit. I would like to see it sort of near-abstract, as they call it — not pure. And new.”

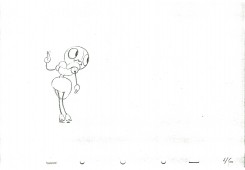

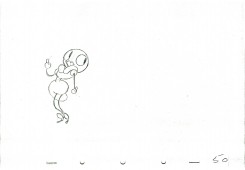

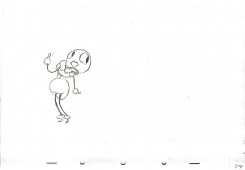

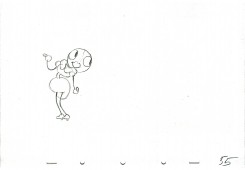

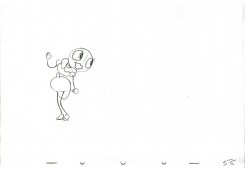

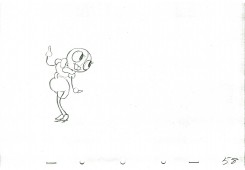

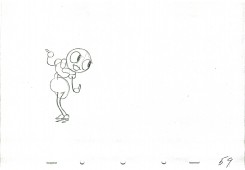

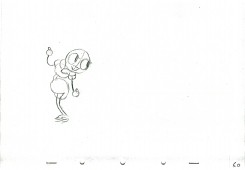

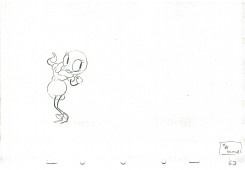

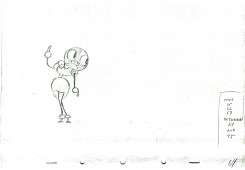

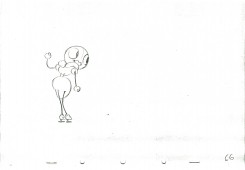

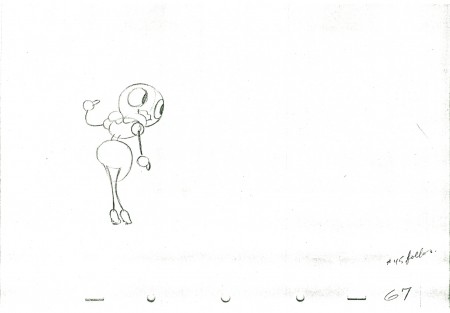

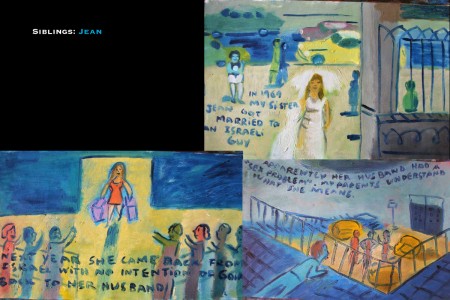

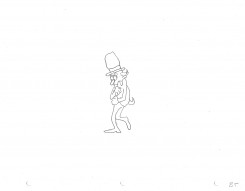

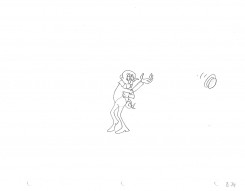

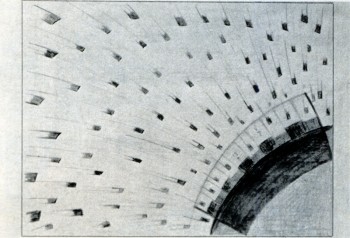

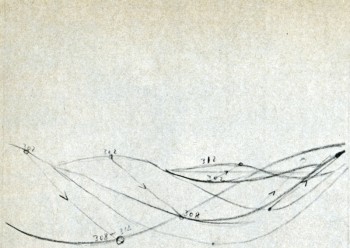

Fischinger’s numerical motion-phase breakdown

for “the Wave” scene in “Toccata and Fugue”

section of FANTASIA.

© Fischinger Trust, all rights reserved.

Perhaps because of the uneasy proximity of Fischinger, Walt exhibits a certain suspiciousness about abstraction, accompanied by a rather defensive attitude towards the prospective audience.

January 24, 1939, p. 2:

Walt Disney: You should give something that the audience will recognize. I don’t think the average audience will fully appreciate the abstract; but I may all be wrong —

Stokowski: Yes, they may be way ahead of us.

or, January 24, 1939, p. 7:

Walt Disney: What will Bach lovers think of this?

Stokowski: They will be against it, I think; but the public will love it.

Walt Disney: Well, the general idea here looks good to me. I only wonder if we’re going a little too gypsy in the color—

or, February 28, 1939, p. 5:

Walt Disney: If we can get a little connection behind this, the public will take to it. It would be better than some wild abstraction that you can’t get anything out of at all. Right there is where the music sounds most like an organ, so the public decides it represents an organ.

or, February 28, 1939, p. 8:

Walt Disney: Do you think we ought to have pictures in mind through this thing? Then we won’t get a conglomerate mess — an abstraction.

or, JuneS, 1939, p. 1:

Walt Disney: There’s a theory I go on that an audience is always thrilled with something new, but fire too many new things at them and they become restless.

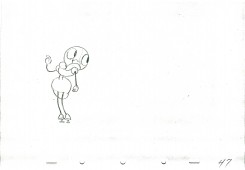

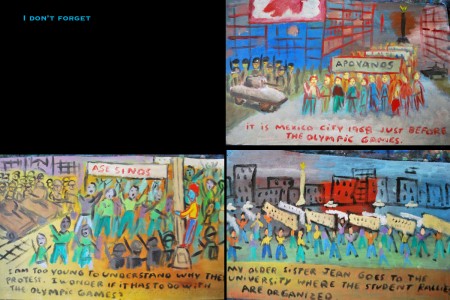

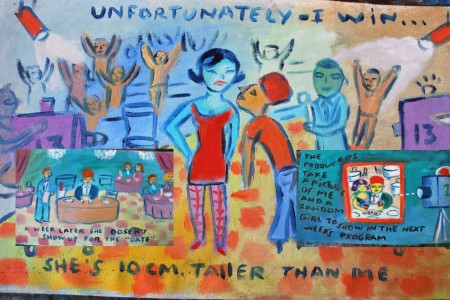

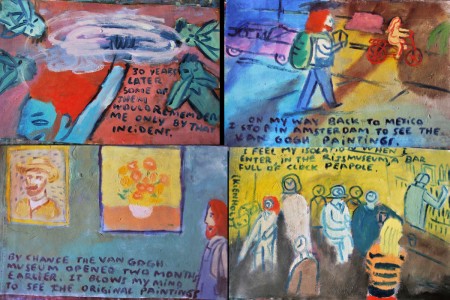

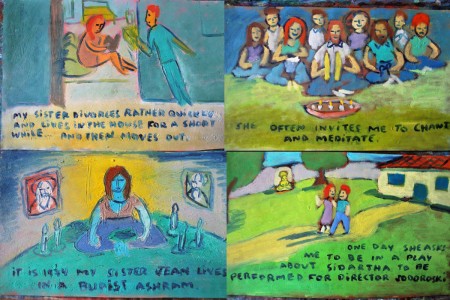

The “wave” scene as it appears in FANTASIA.

©Walt Disney Productions.

Fischinger’s assertions about the unhealthy competitive committee work at Disney would seem to be borne out by the conference notes in which we see during nine month’s of work on the “story” incredible floundering, dreary discussions and re-discussions of each scene, groping and pushing without any controlling factor besides making an entertaining film.

Because he knew little English, Fischinger never spoke up during these story conferences (neither did Kay Nielsen), and further became the butt of endless practical jokes on the part of his jealous co-workers. Some fun-loving boys of the Disney staff, unwilling to deal maturely with the plight of a refugee artist, pinned a swastika on Oskar’s office door September 1, 1939, the day the Nazi armies invaded Poland. Fischinger applied for a release from his contract and after two months of red tape, terminated his employment at Disney, October 31, 1939, Halloween.

Fischinger kept about 100 of his sketches and drawings for the Bach “Fugue”, including some lovely pastels showing melting meanders and supple lozenges much as they appear in the final FANTASIA, as well as half-a-dozen beautiful images that were probably never realized on film. The most extensive unit involves twelve poster-color and 60 pencil drawings (with numerical motion-phase breakdowns) that detail the sequence in which alternating left-and-right-hand “waves” surge toward the viewer. While this turned out to be one of the more impressive moments in the Disney film, a comparison with Oskar’s original sketches shows how much more powerful, subtle and imaginative the sequence might have been if Fischinger’s intentions had been honored — with his choice of monochromatic turquoise and celadon hues for the (somewhat flatter) wave motion overlayed with scintillating geometric figures in browns, Chinese red, and graduated yellow/oranges, all of the elements flowing cogently and vigorously out of each other, as opposed to the simplified Disney image of fat, melon-ribbed waves slightly off-balance in shades of flagrant purple distractingly at constrast in “realism” to the (needlessly) clouded sky behind. All in all, the Disney version of the “Fugue” seems painfully close to the Paramount adulteration of ALLEGRETTO.

Much of Fischinger’s work seems entirely lost. After looking at some of Oskar’s sketches (August 21, 1939, p. 3), Walt Disney comments, “I think the contrast of black and white, and then a little color coming in, would stand out. ” but I don’t think such an effect reached the final version of FANTASIA. Evidently some of Fischinger’s own animation was filmed at least in the pencil test stage, since after viewing some material on a moviola Disney comments (August 21, 1939, p. 7) “Oskarhas a pulsing effect in his test.”

To me, Disney was actually the loser in the matter. Each year Fischinger’s genius and the sincere consistencly of his films becomes more widely acknowledged, while every year the moments of unbearable kitsch, lapses of taste, questionable values, and hodge-podge of stylistics that mar most of the Disney Studio product are becoming more obvious to everyone. For all its considerable virtues of self-parody, rich color and design, etc., FANTASIA falls easily victim to its own shortsightedness so that the burlesque of Bozetto’s ALLEGRO NON TROPPO carries devastating bite.

At least Fischinger had a few of the last laughs in the matter. After leaving the Disney Studios, he devised a set of seven superb collages, among his most charming and highly prized works, showing Mickey and Minnie Mouse (cut from comic books) “reacting” to reproductions of abstract paintings by Kandinsky and Bauer (cut from a 1938 Guggenheim Museum catalogue). And years later, when Disney made the documentary TOMORROW THE MOON, they inadvertantly honored Oskar by using a clip of his pioneer special effects of the rocket launching from Fritz Lang’s FRAU IM MOND, made a quarter of a century earlier.