- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

- The following article was printed in Sight and Sound, Spring 1974 issue. It begins with Art Babbitt‘s 1934 character analysis of Goofy and is followed up with Dick Williams’ 1974 analysis of Art Babbitt. Dick’s comments aren’t always on the money: Babbitt animated a good share of Rooty Toot Toot, but he didn’t animate most of the film. (As a matter of fact, Grim Natwick’s animation of Nellie Bly on the witness stand is, to me, the standout animation of the film.) Babbitt animated the bartender and the trial lawyer.

You can see the film on YouTube, here.

I previously posted the first half of this article with all the Goofy model sheets that it accompanied. You can see that here.

(The original, unfortunately, contains the “N” word instead of “coloured boy” as this edited version offers.)

__________________________

.

Goofy and Babbitt

by Art Babbitt and Richard Williams

.

Two of the great artist-animators of the golden years of the Disney Studios, Art Babbitt and Grim Natwick, were working and teaching at the Richard Williams Studios in London last summer. To parallel Babbitt’s 1934 character analysis of Goofy, which has not previously been published, Richard Williams gives an impression of the animator himself.

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE GOOF—JUNE 1934

In my opinion the Goof, hitherto, has been a weak cartoon character because both his physical and mental make-up were indefinite and intangible. His figure was a distortion, not a caricature, and if he was supposed to have a mind or personality, he certainly was never given sufficient opportunity to display it. Just as any actor must thoroughly analyse the character he is interpreting, to know the special way that character would walk, wiggle his fingers, frown or break into a laugh, just so must the animator know the character he is putting through the paces. In the case of the Goof, the only characteristic which formerly identified itself with him was his voice. No effort was made to endow him with appropriate business to do, a set of mannerisms or a mental attitude.

It is difficult to classify the characteristics of the Goof into columns of the physical and mental, because they interweave, reflect and enhance one another. Therefore, it will probably be best to mention everything all at once.

Think of the Goof as a composite of an everlasting optimist, a gullible Good Samaritan, a half-wit, a shiftless, good-natured coloured boy and a hick. He is loose-jointed and gangly, but not rubbery. He can move fast if he has to, but would rather avoid any over-exertion, so he takes what seems the easiest way. He is a philosopher of the barber shop variety. No matter what happens, he accepts it finally as being for the best or at least amusing. He is willing to help anyone and offers his assistance even where he is not needed and just creates confusion. He very seldom, if ever, reaches his objective or completes what he has started. His brain being rather vapoury, it is difficult for him to concentrate on any one subject. Any little distraction can throw him off his train of thought and it is extremely difficult for the Goof to keep to his purpose.

Yet the Goof is not the type of half-wit that is to be pitied. He doesn’t dribble, drool or shriek. He is a good-natured, dumb bell what thinks he is pretty smart. He laughs at his own jokes because he can’t understand any others. If he is a victim of a catastrophe, he makes the best of it immediately and his chagrin or anger melts very quickly into a broad grin. If he does something particularly stupid he is ready to laugh at himself after it all finally dawns on him. He is very courteous and apologetic and his faux pas embarrass him, but he tries to laugh off his errors. He has music in his heart even though it be the same tune forever, and I see him humming to himself while working or thinking. He talks to himself because it is easier for him to know what he is thinking if he hears it first.

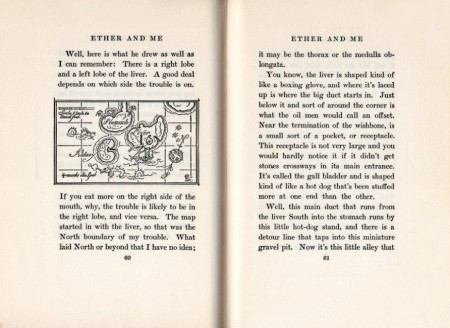

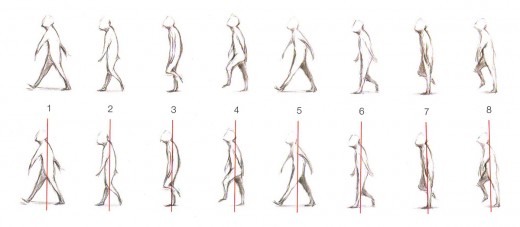

His posture is nil. His back arches the wrong way and his little stomach protrudes. His head, stomach and knees lead his body. His neck is quite long and scrawny. His knees sag and his feet are large and flat. He walks on his heels and his toes turn up. His shoulders are narrow and slope rapidly, giving the upper part of his body a thinness and making his arms seem long and heavy, though actually not drawn that way. His hands are very sensitive and expressive and though his gestures are broad, they should still reflect the gentleman. His shoes and feet are not the traditional cartoon dough feet. His arches collapsed long ago and his shoes should have a very definite character.

Never think of the Goof as a sausage with rubber hose attachments. Though he is very flexible and floppy, his body still has a solidity and weight. The looseness in his arms and legs should be achieved through a succession of breaks in the joints rather than through what seems like the waving of so much rope. He is not muscular and yet he has the strength and stamina of a very wiry person. His clothes are misfits, his trousers are baggy at the knees and the pant legs strive vainly to touch his shoe tops, but never do. His pants droop at the seat and stretch tightly across some distance below the crotch. His sweater fits him snugly except for the neck, and his vest is much too small. His hat is of a soft material and animates a little bit.

It is true that there is a vague similarity in the construction of the Goof’s head and Pluto’s. The use of the eyes, mouth and ears are entirely different. One is dog, the other human. The Goof’s head can be thought of in terms of a caricature of a person with a pointed dome—large, dreamy eyes, buck teeth and weak chin, a large mouth, a thick lower lip, a fat tongue and a

bulbous nose that grows larger on its way out and turns up. His eyes should remain partly closed to help give him a stupid, sloppy appearance, as though he were constantly straining to remain awake, but of course they can open wide for expressions or accents. He blinks quite a bit. His ears for the most part are just trailing appendages and are not used in the same way as Pluto’s ears except for rare expressions. His brow is heavy and breaks the circle that outlines his skull.

He is very bashful, yet when something very stupid has befallen him, he mugs the camera like an amateur actor with relatives in the audience, trying to cover up his embarrassment by making faces and signalling to them.

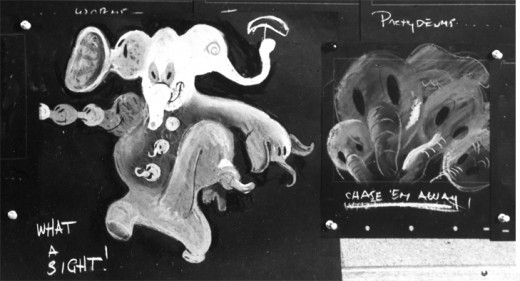

He is in close contact with sprites, goblins, fairies and other such fantasia. Each object or piece of mechanism which to us is lifeless, has a soul and personality in the mind of the Goof. The improbable becomes real where the Goof is concerned.

He has marvelous muscular control of his bottom. He can do numerous little flourishes with it and his bottom should be used whenever there is an opportunity to emphasise a funny position.

This little analysis has covered the Goof from top to toes, and having come to his end, I end.

ART BABBITT

.

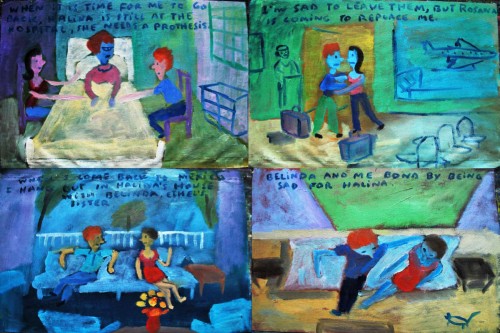

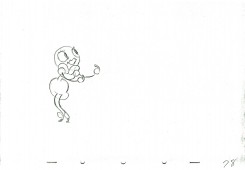

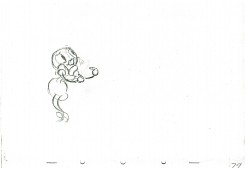

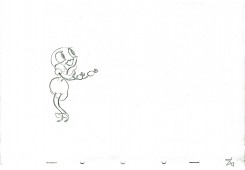

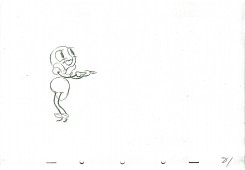

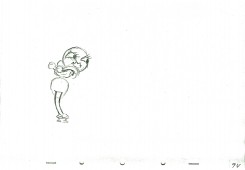

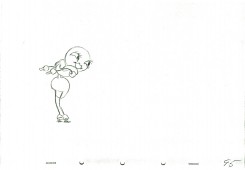

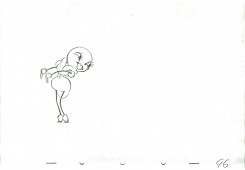

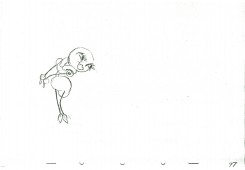

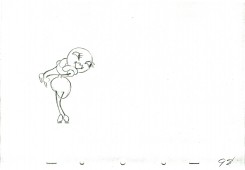

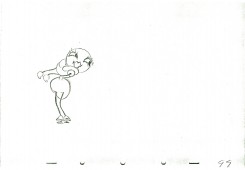

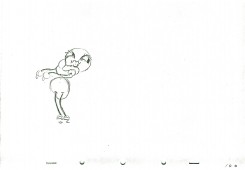

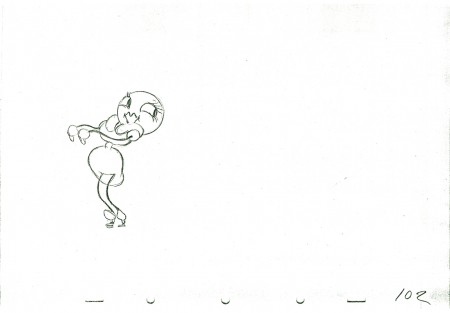

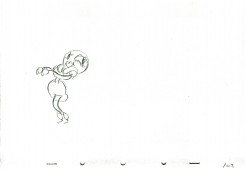

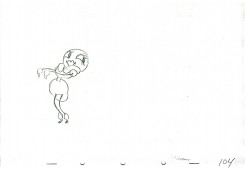

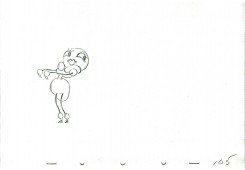

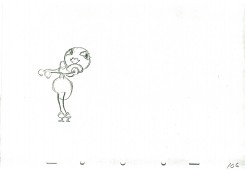

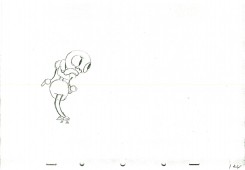

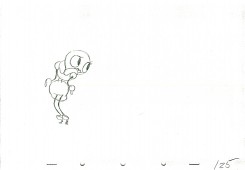

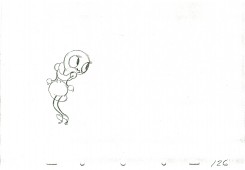

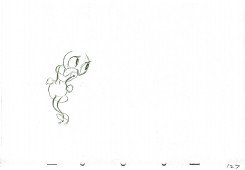

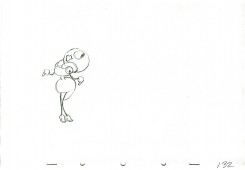

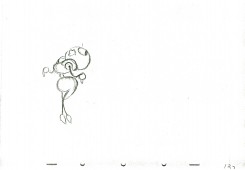

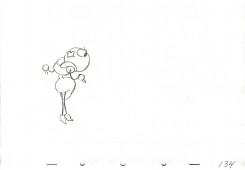

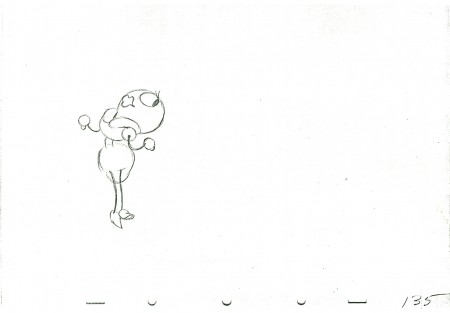

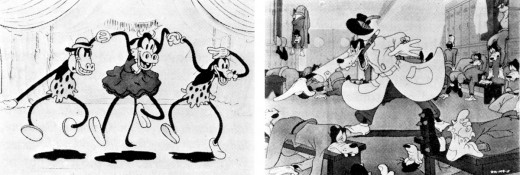

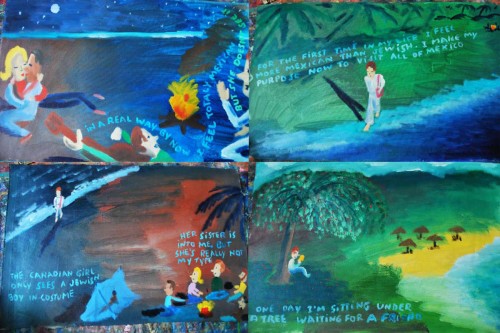

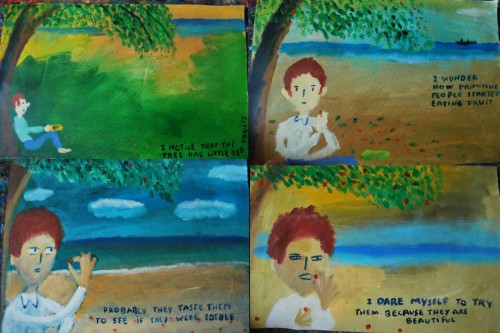

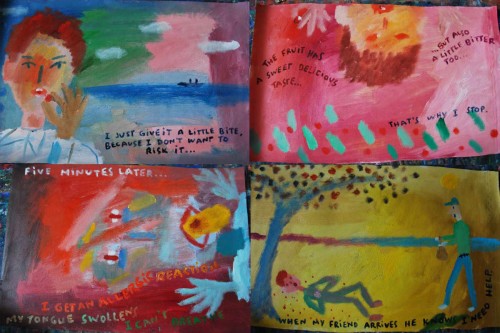

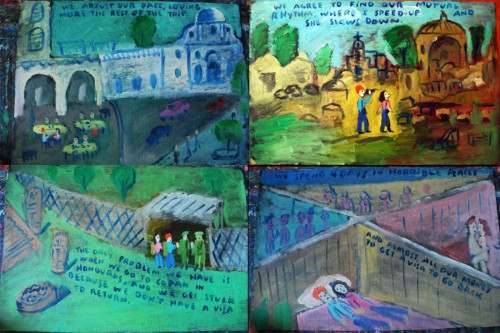

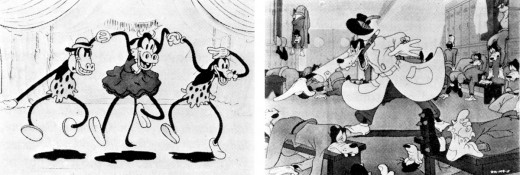

‘Orphans’ Benefit’ (1934). The Goof after Babbitt: ‘How to Play Football’ (1944)

.

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF THE ANIMATOR—JANUARY 1974

.

He is a funny mixture. He has the bearing of a Marines sergeant (which he was during the war, after leaving Disney following the strike in which he was the principal figure); but he has the mind of a Viennese doctor—which is what he wanted to be. In his youth he always wanted to go to Vienna and study psychiatry; but he couldn’t because he was a poor boy from Iowa with relatives to support. So he went to New York and taught himself to be a commercial artist; and gradually got into animation—starting, I think, through Paul Terry.

Arriving at Disney, he was one of four animators on Three Little Pigs; and of course that was the great breakthrough in personality animation. Then he animated Goofy, and worked on shorts in preparation for Snow White. In the first Disney feature he animated the Queen where she was beautiful, up to the point where she is transformed into the hag. In Pinocchio he did most of the animation of Gepetto, and Gepetto almost looks like him. He had that sort of versatility, to characterise the horrid queen or the sentimental wood-carver. Then in Fantasia he did primarily the mushroom dance; but he was animation director on a lot of other material. On Dumbo he was a supervising animator.

The strike came in 1941. Babbitt had had a personal confrontation with Disney over the low payment of assistants; and Disney ill-advisedly fired him, giving as a reason his u-nion activities. This was directly in contravention of the Wagner Labor Relations Act, and the

U-nion took a strike vote. Babbitt fought Disney through all the courts; and they were obliged to reinstate him, for an uncomfortable period during which Disney would pass him in the corridor without speaking or even looking at him. He stood it for a year; then he quit.

After the war he and Natwick were with Hubley at UPA – Art did most of Rooty Toot Toot. Later he was with Hanna and Barbera. I had heard about him for years before I finally came to meet him. He had seen some of our work, and though he’d not exactly liked it (it was pretty slick) had decided that ‘here are some people trying to do an honest job, and that’s the first time I’ve seen that in ten years.’ He wasn’t all that impressed, but he went to the heart of it.

It turned out he was very interested in teaching people. He was thinking of writing a book to instruct people; and he’d done a course at U.S.C. of which we had copies of students’ notes. As it happened he had a fire at his house and all his own lecture notes were burned. So we were able to send him these student notes. He said they were all wrong; but it was something. Then finally I asked him straight out if he would come over and teach us, because we had gone as far as we could go on our own.

He is a great teacher. He has an astonishing lucidity. Most animators are completely incoherent; they are unable to tell you what they are doing. But Art doesn’t have any difficulty in showing you how a thing works. He just says: ‘Did you notice that that worked because such and such . . . and Hubley did this thing this way?’ And when Art says something is wrong, he’s invariably right—if you want it to work. He’ll say: ‘If you want the wheel to go round, this is the way to make it go round. This is the way to make a cypher for making it go round. And this is another way they used to give the impression of it going round. And your problem is that you are to do it with square wheels.’ He is completely eloquent. I’m sure that at Disney they created a language about what they were doing; and I’m equally certain that it was he who largely gave a verbal form to it, so that the others could understand it. He has a surgeon’s mind; which, I gather, Disney had also.

When he taught in our studio he insisted that people take the course. He started off by saying: ‘Please, in my lectures, do not be British. Be crude, be revolting; ask stupid questions. Please do not be polite; otherwise I’m wasting my time.’ He’s as tough as nails; yet it literally hurt him when someone couldn’t get a thing right, couldn’t understand it. Then when they got it right, he would dissolve in warmth. His patience was beautiful.

He knows so much about everything— about symphony construction, about the visual arts, about everything to do with the medium. He once decided he would teach himself to play the piano. He’s the one in the famous Disney story —when he was learning to play the piano, and Disney said, ‘What are you—some kind of fag or something ?’ He hated Disney for that, because he wanted to understand music to apply it to animation. He knew that Fantasia or something like it was inevitable.

On the course he told us: ‘An animator must possess a curiosity about everything that exists or moves . . . must be a student of everything that might or does exist. From the shiver of a blade of grass—affected by an invisible breeze—to the behaviour of a starving hobo eating the first steak he has had in years. From a baby, tentatively trying to walk for the first time—to an elephant doing the can-can.’

I just saw Fantasia again and the Dance of the Mushrooms; and he was doing things there—treating perspective as a subsidiary action—that no one else was doing at the time. And he does not do it by feel, as I might, but because he’s worked it all out and analysed it. On the course he would say: ‘This is the cliché. This is the formula. And this is how to break it.’ He would set up the rules and then make you bust them.

And as well as the analytical capacity and the intelligence is the ability to start from basics—to deal with the most minute detail. He knows how the labs process the material; the way celluloid is made, the way the pencil is made. People who know that kind of thing don’t usually have artistic ability into the bargain. The ability to discern basics extends to his gift for statements that seem entirely simple and yet reveal vital things one often has not recognized : ‘We must learn to create movements if necessary that are caricatures of reality— but done with such guile they are always convincing.’ ‘We must expand our sense of caricature—to realise that we are not simply exaggerating external appearances— but more important, the inner character, the mood, the situation. A caricature is a satirical essay, not just doubling the size of a bulbous nose.’

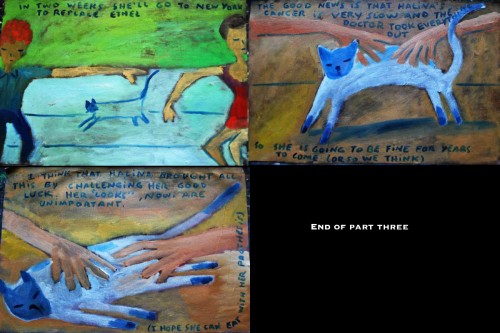

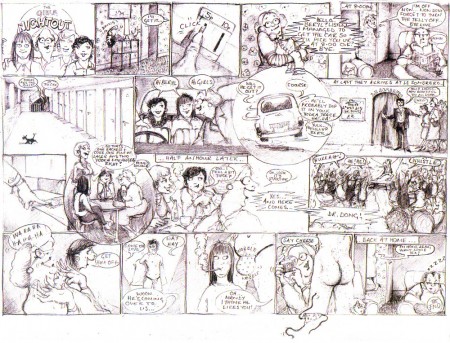

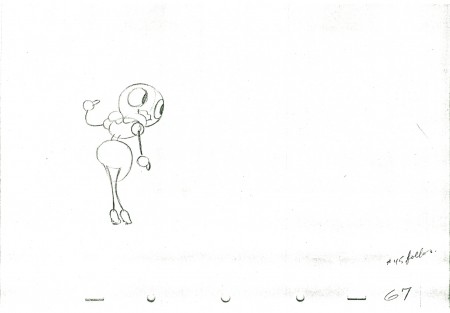

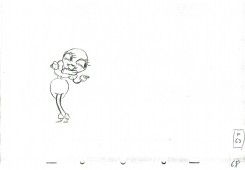

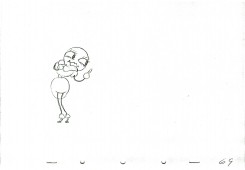

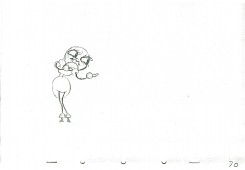

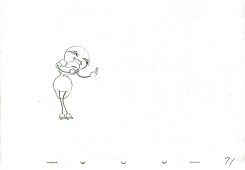

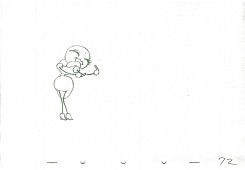

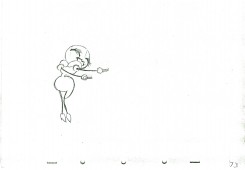

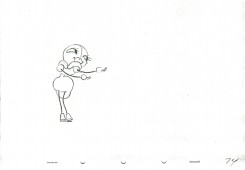

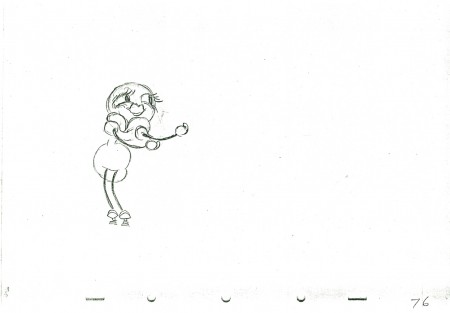

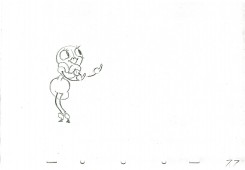

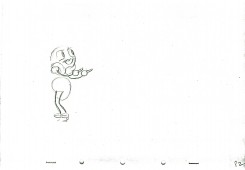

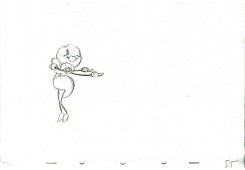

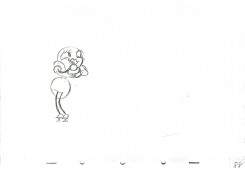

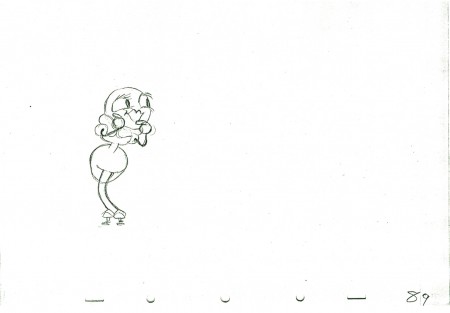

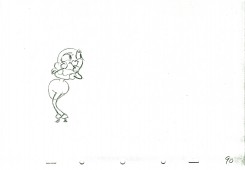

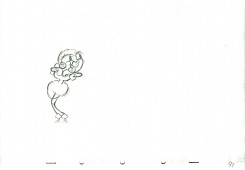

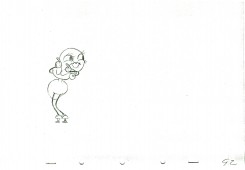

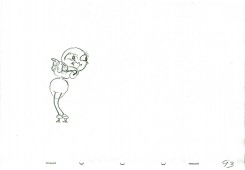

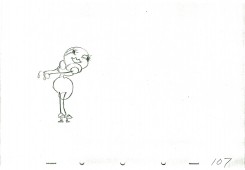

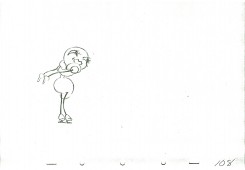

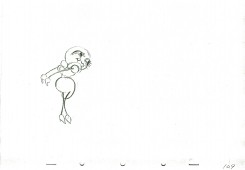

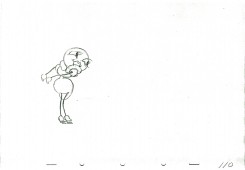

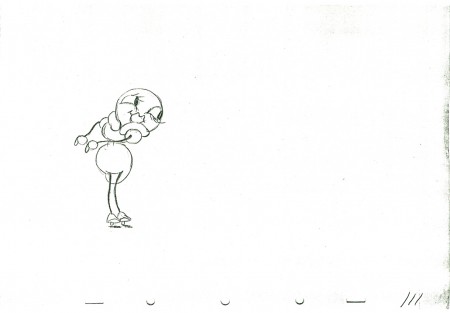

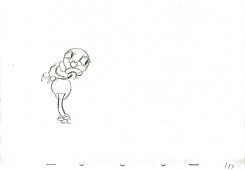

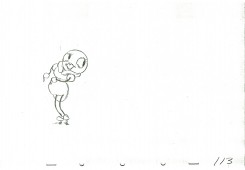

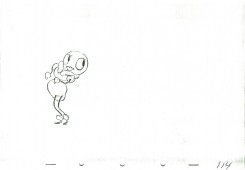

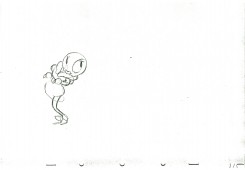

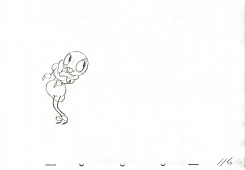

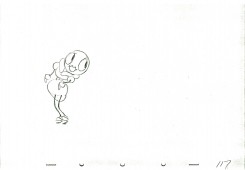

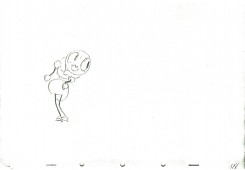

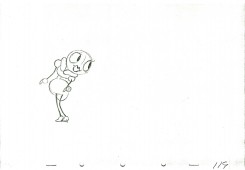

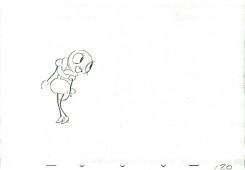

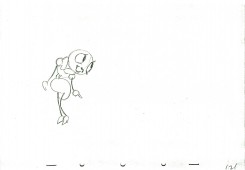

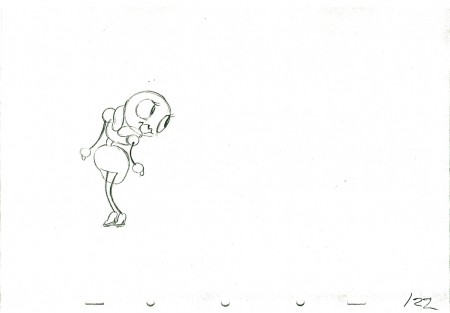

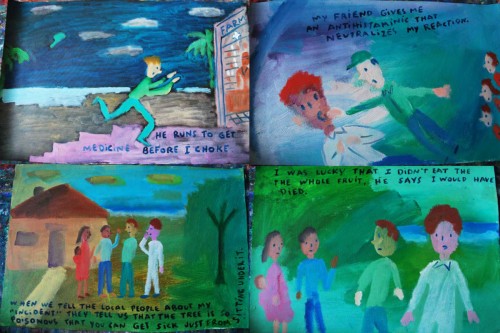

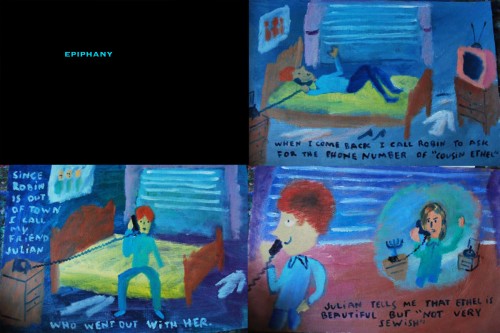

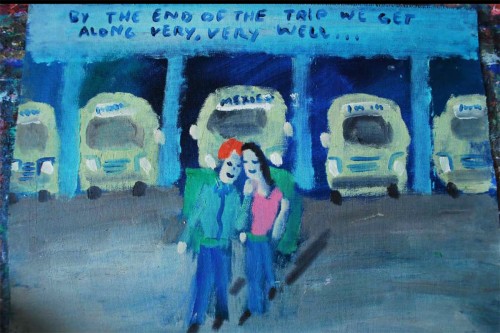

A Babbitt scene from Williams’ Cobbler and the Thief..

My portrait is idolatry, maybe; but how do you not idolize someone who after more than forty years work in his and your medium still can find it ‘wonderful, exciting, exacting … A medium that has barely been discovered, let alone explored. A medium that can be an art form that encompasses practically all other art forms. A medium that can gratify aesthetically, that is not earth-bound, that can be an invaluable aid in teaching everything from elementary chemistry to the Theory of Relativity.’

RICHARD WILLIAMS

1

1