- Here is an article about Ronald Searle pulled from a copy of Cartoonist Profiles issue #4. It dates back to November 1969.

RONALD SEARLE

Writes from

FRANCE

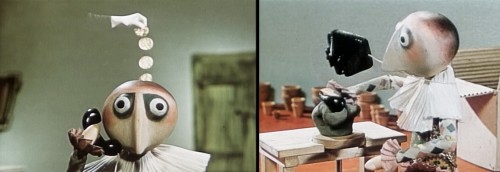

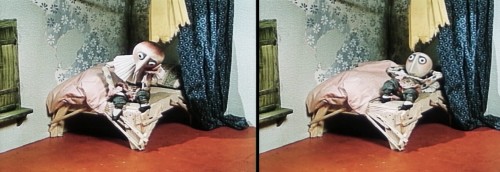

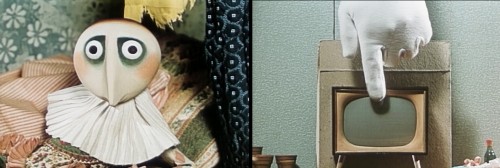

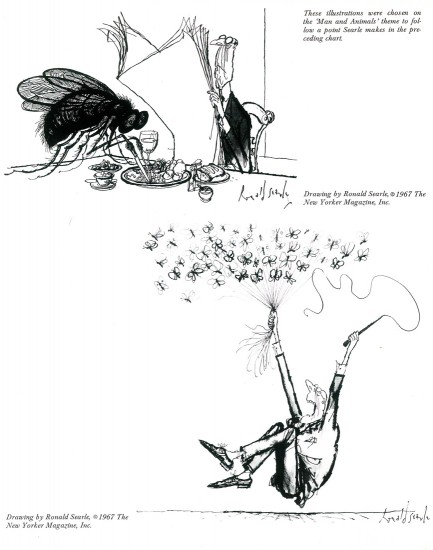

The following article, and the accompanying ‘ideas chart’, were written for CARTOONIST PROfiles by RONALD SEARLE, the noted European cartoonist who makes his headquarters in Paris. He created St. Trin-ian’s, which has become a part of English folklore, has illustrated more than 40 books in the past 23 years, has designed sets and costumes for films, made his own cartoon film John Gilpin’, and constantly does work for American, French and German magazines. One of his publishers describes him as Europe’s most accomplished cartoonist — a macabre black humourist, a lynx-eyed reporter, a gagman of genius, a draughtsman of the stammering line and the delirious arabesque that inimitably characterises his world.

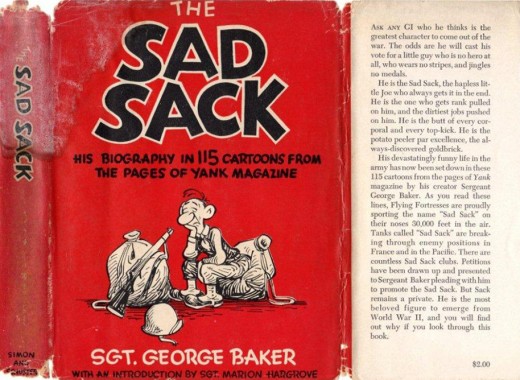

My childhood was unremarkable apart from the fact that I was born and brought up in one of the most beautiful and ancient university towns in England. I drew before I could write legibly (I am left-handed), and I swapped comics in the school yard; no doubt gathering supplementary festering sores in the process. The dog-eared sheets which passed from filthy hand to filthy hand, were hardly recognizable as copies of “Comic Cuts”, “Film Fun” and “Chips ” — the most desirable titles at that time. The more pictures there were to a page and the less text, the happier I was, like all lazy-minded kids. My imagination was almost entirely visual and only faintly literary. However, my great love was books. I devoured everything in our town library, beginning with the infant shelves and graduating at the age of twelve to the adult library. My thirst was insatiable. I frequently took out five books in a day; making my way through A-B: “British Butterflies in Colour”(c. 1894)to Y-Z: “Zjululand, The journal of my encounters in” (c. 1901, I guess). By the time I was 13 I wanted my own library and I began to haunt the secondhand bookstalls and barrows in Cambridge. I earned, begged, and scraped together every penny I could and within five years I had accumulated some 500 volumes for a few pennies apiece. At the outset of my buying, one Saturday, I tumbled onto two or three volumes about caricature, at 6d. each. One of these volumes was Spielmann’s “History of Punch”. I had already decided I would be either an artist or an archeologist and with juvenile confidence I now added the intention of being a “Punch “cartoonist.

That Autumn I enrolled for evening classes in the Cambridge Art School. This had caused some argument between my mother and father for the fee was 7s.6d. a term (about $1.50 then), and we could not afford it. But the money was scraped together somehow. I can guess now that my mother probably put a thicker piece of cardboard in her shoe.

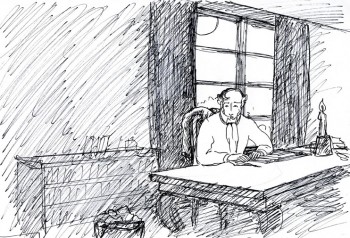

I was obsessed with drawing, and scratched away incessantly. I scrambled through the day at school and my homework afterwards and then rushed off at six in the evening, for three hours of art. By the time I was fourteen I had graduated from the plaster Discobolos into the life class, and painfully shaded my way through several years of floppy-breasted nudes with blue toes and purple legs. It was difficult to keep the fen winds, which blew across the North Sea from Siberia, out of our life-room. Side by side with my art-school work I scribbled comic drawings. The next year, when I was 15, the cartoonist of the local paper left for London and higher things. I stuck a cartoon through the letterbox of the “Cambridge Daily News”, utterly confident that the editor would take it, and that this would solve an important economic problem for me. He did take the cartoon and asked me for more at 10s.6d. a week (about $2.00 then). This represented all the drawing materials I needed, a bit for the family and something over for me.

I continued with those weekly cartoons from 1935 until the war, almost without a break. They were dreadful, but they taught me how to draw for reproduction.

By 1938 the local council had awarded me a full-time art scholarship, and I sweated away for over a year, as a “real, full-time artist”. Lautrec was more precocious, but he was never as happy as I was then. By the time I went into the army, at the outbreak of war in 1939, I had completely saturated myself in anatomy, perspective, history of costume, architecture, life drawing, and all subjects required for passing the Min. of Ed. Drawing Diploma. I missed failure by 2%, but achieved the solid Bolshi-Academic grounding characteristic of Cambridge in the ’30′s.

Also in 1939, I found on a secondhand bookstall, a small monograph by Marcel Ray on the work of George Grosz. It cost me 2s. and changed my artistic direction. I had already established a pedestal for Picasso as the foremost of my living heroes, and I was still grinding my teeth at being unable to raise the $35.00 he was asking then for a pen drawing at a local gallery. Forain I marvelled over, despite his loaded anti-semi-tism, and he had joined the line with Gillray, Rowlandson and Cruikshank, as my self-appointed guardian angels. Daumier’s work was difficult to find, and I had not been able to form an opinion of him then. Goya, however, was one of my gods, and I still day-dream that one day the Prado will drop me a note during a period of stocktaking, to say that they wonder whether I might be interested in accepting a couple of drawings of which they have duplicates.

If anyone influenced me in my work it was on the basis of draughtsmanship, rather than painting. I saw in line then, as I still mainly do now. Above all I admired “Roly’ Rowlandson, with his wit, genius, ability to handle line, ability to range from the broadest and most clownish grotesque to a cunning subversive charm. I cannot say that I have ever consciously had the desire to copy anybody. But if I have been influenced, it is by Rowlandson. And Grosz. Although I had known little about Grosz until I got the Marcel Ray book. I had seen the occasional Munchen album from the ’20′s, and had heard of his flight to America. From time to time I had come across a drawing of his in “Esquire”. But now he fitted into place for me. Grosz exposed the rotting military mind; the filth of war and the stench that lingered after it — and, how he could draw! With this book of his I headed off for my seven years as a soldier.

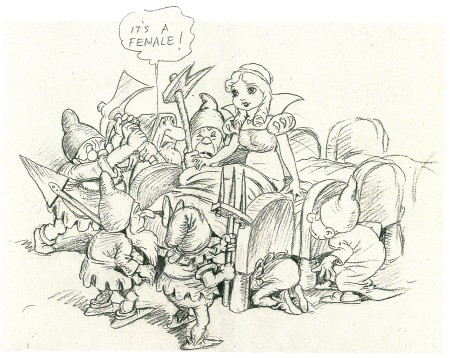

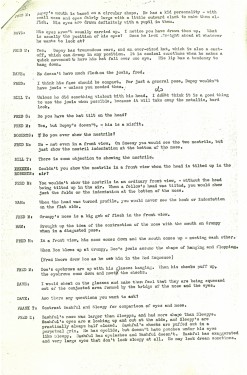

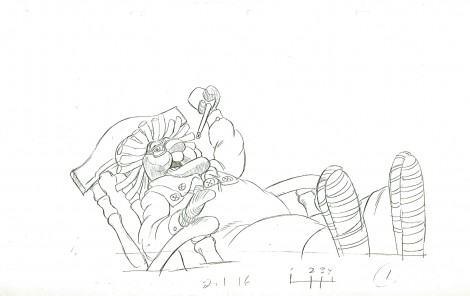

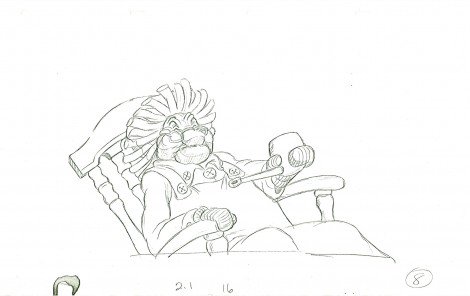

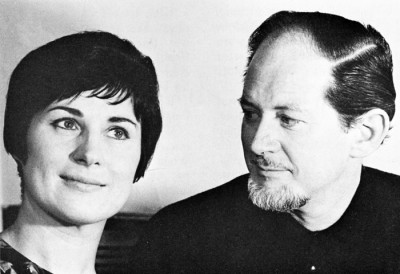

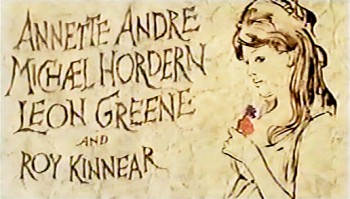

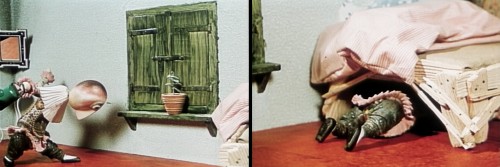

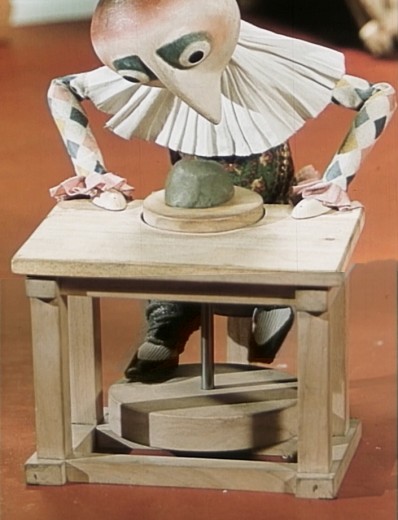

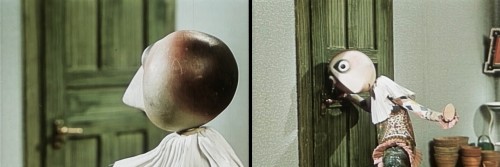

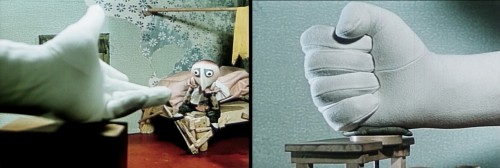

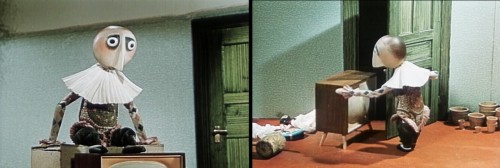

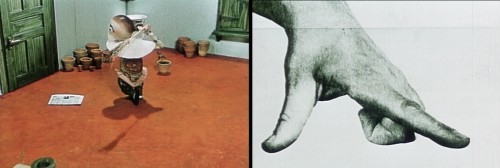

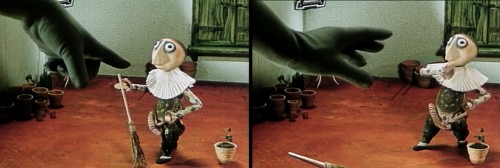

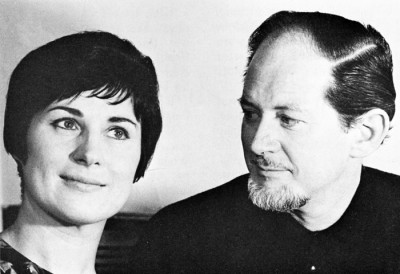

Searle and Monica on location in Rome last year, during the

filming of Paramount’s “Those Daring Young Men in their Jaunty Jalopies”,

for which he designed the animated credits sequence. Searle had previously

designed a similar sequence for the 20th Century Fox film “Those

Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines”. Working with Searle was

the lively young English group “Trick-film”, who made the very successful

“Yellow Submarine”, and with whom Searle is now associated in the

formation of an animation workshop in London.

During those seven years I never stopped drawing. I was a conventional art-student when I went into the army. Before 1939 I had rarely left the town in which I was born. When I came out of a Japanese prison in 1945, after four rough years, I had enough experience of humanity and inhumanity to provide me with a measuring-stick for a considerable part of my life. I also had the facility of seven years of practical application with my drawing. I had documented almost every move I had made, from my first miserable night in the army to the other side of the world and back.

I had been isolated from the world for almost four years; but had also developed in that isolation.

It was then that I was faced with earning my living. I had nothing but fantasies in my head, and a small army pension between me and the post-war wolves at the door while I was getting rehabilitated and thinking about long-term plans for the future. It seemed to me that the only fast and easy way of keeping myself fed was to sell cartoons. So I sold cartoons. This I rapidly discovered needed no particular ability apart from being able to communicate a personal way of looking at things; and apart from having enough nose to smell out the flavour of what was going on and putting it to use. Coming as I did from an atmosphere of stinking cells, wasted bodies and grim humour, my humour was ‘Black’. But so was the post-war climate of rationed England, and my work found a ready market there. I cannot say that I ever thought of cartooning as an ultimate career. All I knew was that I wanted to eat and that I wanted to draw, and this was one way of being able to get some of the disgust I felt for human behavior into print (comically wrapped-up for public consumption). At that point I became a part-time cartoonist. I still am.

Drawing for me has never been a case of therapy because I was shy, or not outstanding in physical activities, or anything else. It was a compulsion. I carried a sketchbook day and night, because I could not stop drawing. To sell a sketch was a pleasure, because it meant a little less economic worry and more freedom to explore. But if I had not sold, I still would not have stopped.

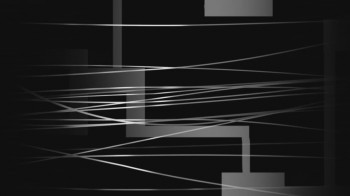

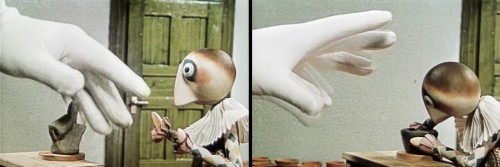

To me line is something which one can explore endlessly, and which keeps me in a constant feeling of excitement and adventure. I know I shall never live long enough to say and do all I want in line. I can only hope to get up each day, bursting to push the exploration a little further. But line is useless if one has nothing to say with it. The artist must be driven with the desire to express something, and use any device to achieve it. He must be perverse. Everybody will want to mould him to their pattern. But in the end he has to satisfy himself — or spend his life trying to please other people.

If satisfaction with one’s work creeps in, the time has come to give up and take to prostitution. A sure sign that there is still hope is when one is miserable at not having met one’s own demands.

The hand is feeble and the artist has still to express with exactitude what his brain conjures up.

Some day it may be possible

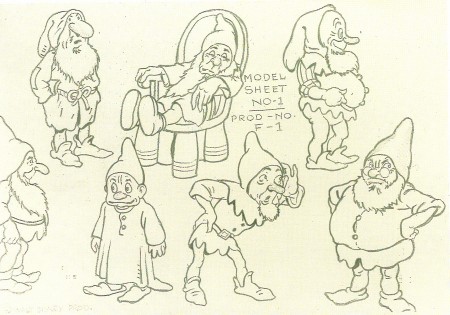

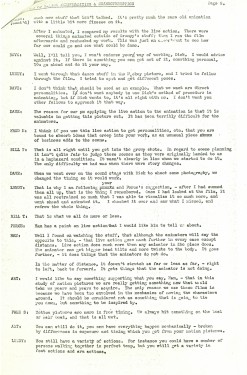

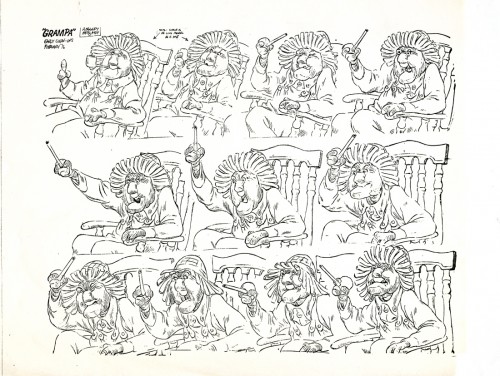

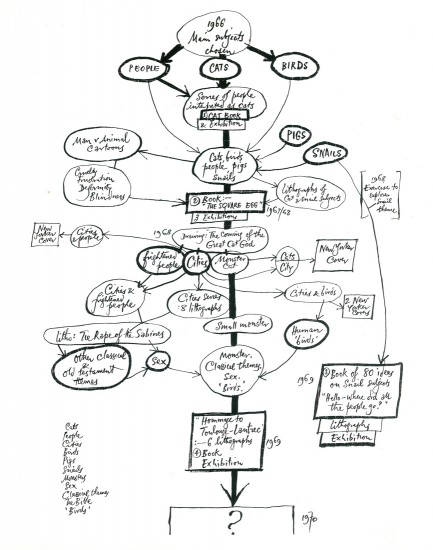

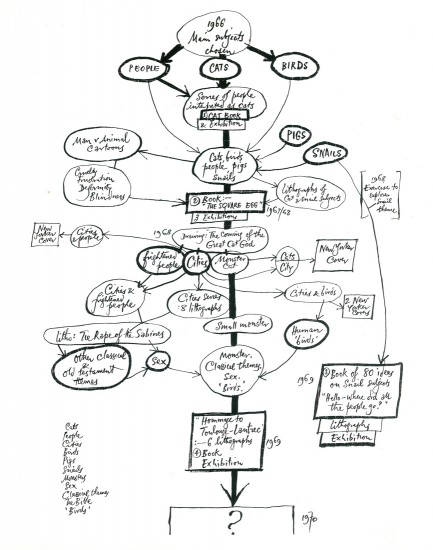

The apple tree on the opposite page was compiled out of curiosity in an attempt to answer the editor’s question: “What routine do you go through to dredge up ideas?”.

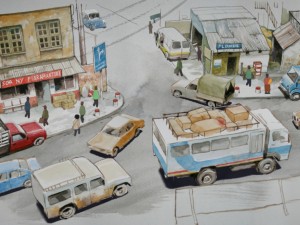

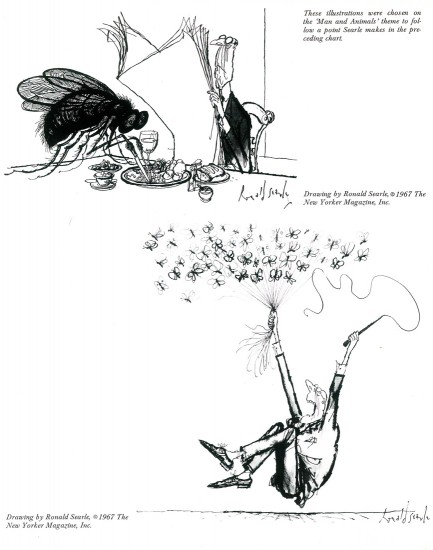

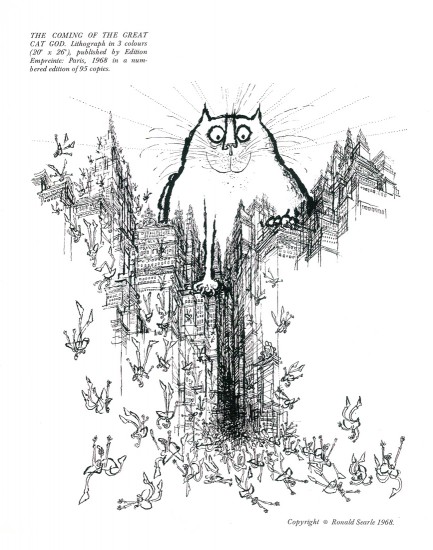

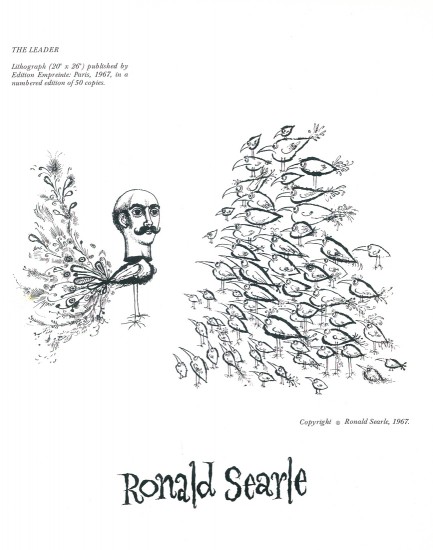

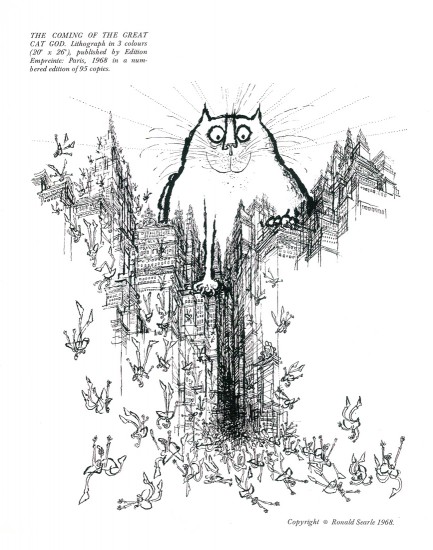

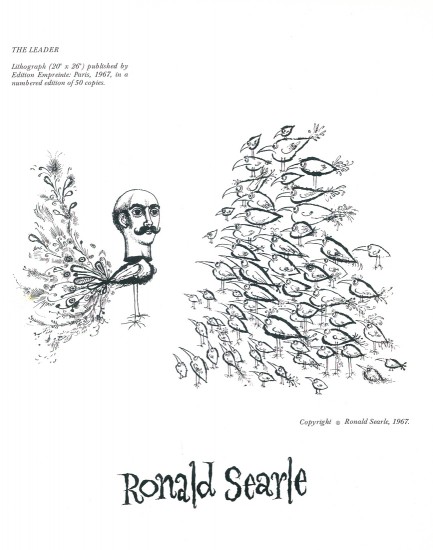

It covers the period 1966-1969, and covers the area of ideas only, as opposed to other work made alongside: Book illustration, cinema animation and so on. In 1966, I set out with three main themes as subjects: Cats, Birds, and People. Subsidiary themes, such as Pigs, and Snails crept in soon after. The first four subjects led me to three books, and the Snails led me to a fourth. Lithographs, New Yorker covers and cartoons, and a series of exhibitions developed alongside. As is apparent from the confusion above, I do not attempt to force ideas, but rather to let them drift inconsequentially — and frequently into a dead end. In this case I started out with Cats in 1966, and arrived at Toulouse-Lautrec in 1969. Some drift! I work with no fixed market in mind. Some ideas may best be expressed in lithography, others as large water-colours, others in pen. When they have been sufficiently developed I start worrying about placing them. The outcome of the three years in question was: some 30 large lithographs; 12 New Yorker cartoons and four covers; four books: “Searle’s Cats” (1966/67), “The Square Egg” (1967/68), “Hello – where did all the people go?” (1968/69), and “Hommage to Toulouse-Lautrec” (1969). In addition, 19 exhibitions in galleries in France, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Switzerland and England were arranged for 1966-1970. Here, either the originals or series of lithographs are for sale. Exhibitions are aided by the fact that, to publish books of this sort at an economic price, they need to be captionless and published in simultaneous co-production in England, France, Germany and America. Most of the material in these books has not been previously published — apart from the occasional sale of serial rights. As a working method it is not particularly scientific, or organized. The only factor I watch is: that whatever I do is thought of as an international idea — that it will have equal appeal in any of half-a-dozen countries. Or be equally rejected.

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

the cover of the issue

1

1