Action Analysis &Animation &Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary &Disney &Illustration &Richard Williams &Rowland B. Wilson &SpornFilms &Story & Storyboards &Tissa David 10 Jun 2013 03:31 am

Illusions – 3

I’ve written two posts about Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston‘s book, The Illusion of Life the last couple of weeks. I came to the book only recently and realizing that I’d never really read the book, I thought it was time. So in doing so, I’ve found that I have a lot to write about. The book has come to be accepted almost as gospel, and I decided to give my thoughts.

There were two major complaints I’ve had with what I’ve read in their book so far, and I spent quite a bit of time reviewing those.

- First out of the box, I was stunned to read that these two of Disney’s “nine old men” said that they’d originally believed that each prime animator should control one, maybe two characters in the film. Then, later in life they decided that an animator should do an entire scene with all of the characters within it. This is not what I’d seen the two (or the nine) do in actual practice. post 1

Secondly, they argue for animating in a rough format, and they give solid reasons for this. As a matter of fact, it was Disney, himself, in the Thirties who demanded the animators work rough and solid assistants who could draw well back them up. Then much later in the book the two author/animators suggest that it’s better for an animator to work as clean as possible with assistants just doing touch-up. This helped out the Xerox process, but didn’t necessarily help for good animation. post 2

The book starts out sounding like it’s going to be a history of Disney animation, but then starts getting into the rules of animation (squash and stretch, overlapping action and anticipation and all those other goodies) exploiting Disney animation art in demonstration. Soon the book moved into storytelling and how to try to keep the material fresh and interesting. It all becomes a bit obvious, but you keep hoping that some great secret will be revealed by the two masterful oldsters.

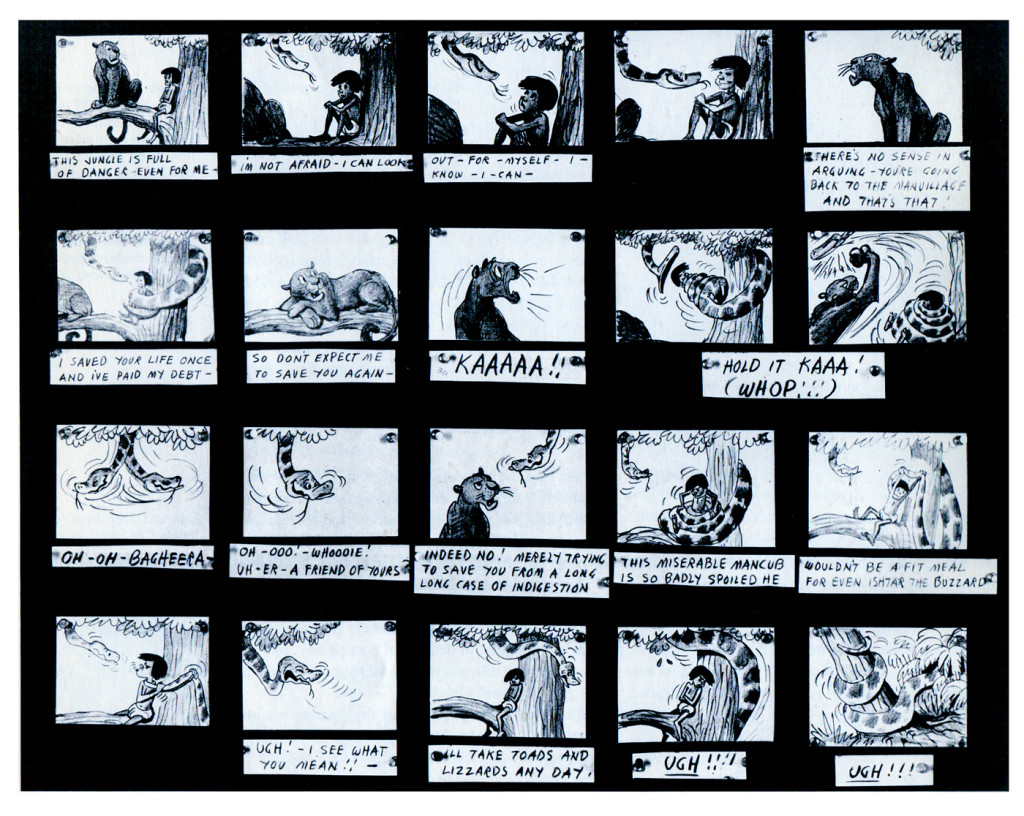

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

They do go into depth about how to develop characters when making animated films. They offer lots of examples from Orville, the albatross in The Rescuers to the three fairies in Sleeping Beauty, but their greatest attention goes to Baloo the Bear in The Jungle Book. They were having a hard time with this guy; they had been trying to do an Ed Wynn type character, until Walt Disney, himself, suggested Phil Harris. Once they auditioned Harris, they knew they were on the right track, and the character kept grabbing more screen time and grew ever larger. In the end, audiences just loved him.

Personally, I’ve always hated Phil Harris’ performance in this film. What was it doing in Rudyard Kipling’s book? When I was a kid, Harris and Louis Prima were the perfect examples of my father’s entertainers. He loved these guys and spent a lot of time in front of the family TV watching the Dinah Shore Show______Tom Oreb designs for Sleeping Beauty.

and other such entertaining Variety Shows with

lots of little 50′s big-band jazz-type acts. I hated it; this was my parent’s kind of music and humor and had nothing to do with me. I was the kid who paid his quarter to see the Walt Disney movies (that was the children’s price of admission in 1959.)

In their book they say they knew he was perfect because generations of kids later (who have no idea who Phil Harris was) still take joy from Baloo. What they forgot is what I knew all along. This was The Jungle Book. If they had been truly creative, they would have developed a character in line with Kipling’s material that would have been an original, not an impersonation of Doobey Doobey Doo, Phil Harris. The same is true of Louis Prima as a monkey. (There was a time when Disney said that they should never animate monkeys because monkeys are funny on their own, in real life. Animation wouldn’t make them funnier.) Sebastian Cabot, as Bagheera, works as does George Sanders as Shere Khan.

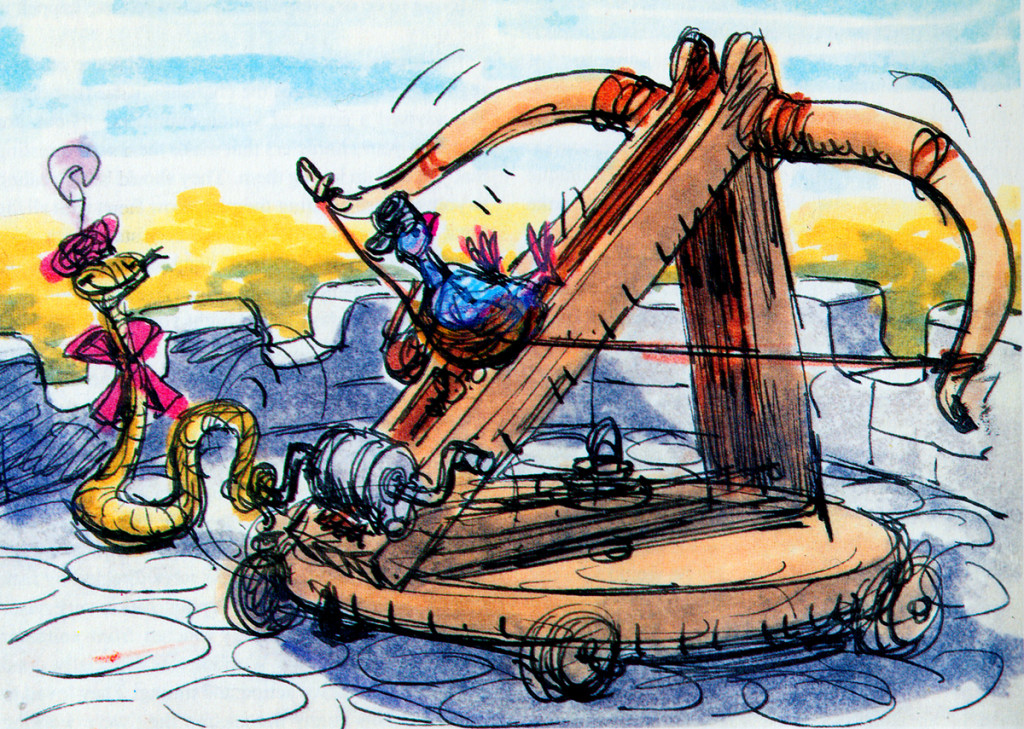

- Right: A discarded sequence from Robin Hood showed a messenger pigeon so fat and heavy he had to be shot into the air. This gave the animators the beginnings of The Albatross Air Lines in The Rescuers.

Phil Harris was so successful, they dragged him into Robin Hood as well. Robin Hood. The very same character from The Jungle Book is now Little John! All those cowboy voices in Robin Hood don’t work either, especially when you mix them up with Brits like Peter Ustinov and Brian Bedford. When these two thespians work against Pat Buttram, Andy Devine and George Lindsey, it’s one thing. Throw in a Phil Harris, and you have something else again. Where are we, the audience, supposed to be? Is it “Merry Ol’ England”? Or is it the lazy take on character development by a few senior animators who have taken license to jump away from the story writers for the sake of easy characters of the generation they’re familiar with. Robin Hood is a mess of a story – even though it’s a solid original they’re working from, and I find it hard to take written advice from these fine old animation pros who take an easy way out for the sake of their animation; shape shifting classic tales to fit their wrinkles.

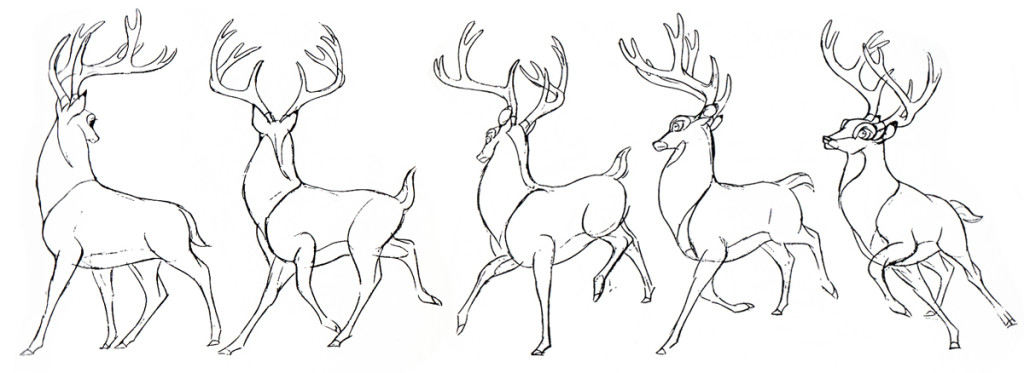

At least, that’s how I see it – saw it. And perhaps that’s why it’s taken me so long to read this book. I felt (at the age of 14 when these films came out) that the Disney factory had turned into something other than the people who’d made Snow White and Bambi and Lady and the Tramp.

They had, in fact, become the nine old men.

The Jungle Book was the last film Bill Peet worked on. He left

before the film was done. He’d had a long, contentious relationship

with Disney. He never felt he’d gotten the respect he deserved.

They were incredibly talented animators, and they certainly knew how to do their jobs. The animation, itself, was first rate (sometimes even brilliant as Shere Khan demonstrates), but try comparing the stories to earlier features. Even Peter Pan and Cinderella are marvelously developed. Artists like Bill Peet and Vance Gerry knew how to do their jobs, and they did them well. When Peet quit the studio, because he felt disrespected, Disney’s solid story development walked out the door.

The animators were taking the easy route rather than properly developing their stories. The stories had lost all dynamic tension and had become back-room yarns. Good enough, but not good.

Today was Nik Ranieri‘s last day at Disney’s studio. He’s definitive proof, in the eyes of Disney, that 2D animation is dead as an art form. This is the end result of some of the changes Thomas and Johnston suggest in their book. The medium took a hit back then; it just took this long for the suits to catch up. Good luck to Nik and the other Disney artists who no longer work steadily in what is still a vitally strong medium.

on 10 Jun 2013 at 9:48 am 1.Luke said …

Spot on. The animator a weren’t being challenged–and the storytelling and writing were lazy. This is what happens when animators get too much control–they get lazy. Not until the late ’80′s, when story material began once again to challenge the animators did the characters they contributed to come to life.

on 10 Jun 2013 at 12:12 pm 2.Milton Gray said …

Wow, Mike, you stated it perfectly. I began working at the Disney studio during Jungle Book, and was disappointed by the very things that you articulated. Then Walt died and things got only worse. I had a very open opportunity to stay on at Disney throughout the 1970s and with a good chance to becoming a full animator, but the movies themselves were getting so bad that I left, hoping to find something better, even if I had to open my own studio (which I eventually did, for a while). I don’t recall if I mentioned this to you before, but while I was at Disney working on Aristocats, I listened in on a meeting conducted by Woolie Reitherman and his layout artists, going over the storyboards for Robin Hood, and Woolie’s primary focus of that meeting was on taking out anything that had any guts at all, and making everything as bland as possible. I was rather shocked that this was so intentional, not just accidental. I have always wanted to be an animator to make characters come alive (rather than just “move”), but I’ve also always been aware that characters first have to come alive in the story stage.

on 10 Jun 2013 at 1:52 pm 3.Roberto Severino said …

Yet another excellent analysis and exploration into the origin of lazily using celebrities as a way to avoid coming up with any original ideas. The practice still persists to this day.

I do not have a problem with using celebrities to voice certain characters as long as their voices are actually distinct and fit the personalities of the characters well. It just becomes arbitrary when overdone when there are countless voice actors who can provide interesting, distinct voices too!

on 10 Jun 2013 at 2:57 pm 4.the Gee said …

I’ve read a lot about the lack of daring and the reuse issues with Woolie Reitherman.

There was no other seasoned vets making counterpoints?

on 10 Jun 2013 at 5:52 pm 5.Nat said …

Studio decay can be a hard thing to avoid. So when something is both commercially and critically successful, it is indeed worth celebrating.

on 10 Jun 2013 at 7:41 pm 6.Shane (Fighting Seraph) said …

To Milton Gray: It seems that you have explained why John K has a strong dislike towards Disney. I wonder if you’re willing to share anymore studio horror stories from the seventies?

To Michael: Great essay as the last two posts on The Illusion of Life. I’ll look forward to the next one.

on 11 Jun 2013 at 10:50 am 7.Milton Gray said …

To Shane: I left the Disney studio in 1971 and never went back, even though the management asked me a few times later to come back. So I don’t have too many firsthand horror stories.

on 11 Jun 2013 at 6:39 pm 8.Chris Webb said …

While I feel bad for Nik Ranieri, the man was employed for 25 years at the same company, which is practically unheard of these days.

“He’s definitive proof, in the eyes of Disney, that 2D animation is dead as an art form.”

I think what is dead as an art form is the “2D Disney movie.” But not 2D.

There is a big difference, and that difference has yet to be completely explored.

on 11 Jun 2013 at 10:02 pm 9.Michael said …

Chris, You’re saying the same thing as me: “. . . in the eyes of Disney, that 2D animation is dead as an art form.â€

on 12 Jun 2013 at 5:20 pm 10.Chris Webb said …

To elaborate further, I guess what I mean is that 2D Disney acting is dead. Or needs to be.

At the risk of offending people, I’ll just flat out say it – in watching Nick Ranieri’s test for Wreck It Ralph, my overwhelming feeling was that Ralph is acting *like a character in a Disney film,* not like something original.

Any of my adult friends who criticize 2D movies state that the character acting in these films is simplified to the point of being uninteresting. Sure the tools of the medium are anticipation, squash and stretch, clear silhouettes, etc. But why in this age can’t Disney acting grow up a little?

In Sylvain Chomet’s movies, the characters don’t indicate nearly as much. Same with Richard William’s animation. Or The Iron Giant. So what happens at Disney that turns every single character into a performer instead of a character you can believe in?

I hate to say this, but in the long run, this may be good for 2D animation as a whole. I think 2D’s been strangled by Disney for way too long. Let’s hope that new and surprising developments are on the horizon. There’s certainly enough talent out there to keep 2D going forever.

on 12 Jun 2013 at 5:21 pm 11.Chris Webb said …

BTW, my comments are by no means a bash on Nick or his abilities. For all I know, he was directed to have Ralph act that way. Just wanted to say that to be fair to him.

on 02 Feb 2015 at 11:30 pm 12.Best Website To Have An Affair said …

It’s hard to come by experienced people about this subject, but you sound

like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks