Animation Artifacts 17 Oct 2006 12:22 pm

Iwerks’ work

- From my earliest days, as soon as I’d learned who he was, I was a fan of Ub Iwerks.

Ub Iwerks.

I began to wonder if it was just the publicity and myth of Iwerks which had followed with him all these years. We read about all those 1930′s East coast animators moving to the West, not to work for Disney but to seek out Iwerks – it was well known that he was the “true artist” behind those Disney shorts.

With Bob Thomas’ 1958 book, The Art of Animation, I read, for the first time, about Iwerks and his importance. Only recently did I begin to wonder how responsible Iwerks actually was to Disney’s success. Was this just that myth being carried over the years? Or was he brilliant?

A quick look at the animation done at the time and we see some basics not yet developed.

A quick look at the animation done at the time and we see some basics not yet developed.

There weren’t many stories written before Disney, so animators divided up their pictures. For example: They’d decide to do a film where Mutt & Jeff would go to Hawaii. One animator would start on the beach and end with them on surfboards. The animator would make it up as he went along until he turned out the required footage – maybe 2 minutes of work. The next animator would pick up Mutt & Jeff on surfboards and take them to being washed up on the beach, etc.

Obviously, the lead animator doled out rudimentary plot points, but a lot was left to the individual animator. Look at the book, Walt In Wonderland by Russell Merritt & J.B. Kaufman to see how Disney started developing stories during this period.

Obviously, the lead animator doled out rudimentary plot points, but a lot was left to the individual animator. Look at the book, Walt In Wonderland by Russell Merritt & J.B. Kaufman to see how Disney started developing stories during this period.

The same was true for animation techniques and methods. Animation burst out of its seams with the creation of Mickey Mouse. Disney had initiated a lot of ground work, but the medium really started growing with the enormous success of Steamboat Willie. Iwerks led the way, not only by the amount of work he did but the quality.

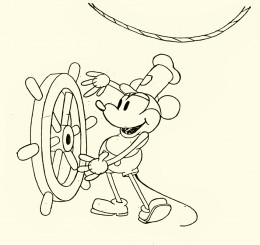

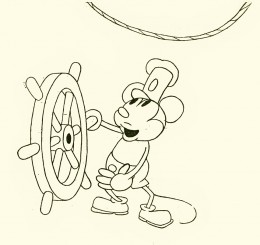

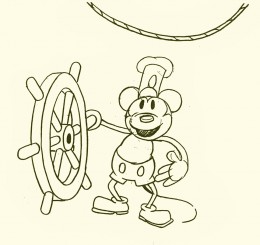

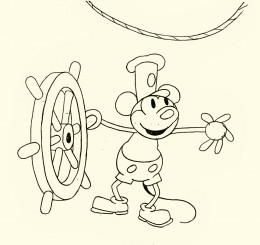

Take a look at these five Iwerks drawings from that short.

Take a look at these five Iwerks drawings from that short.

One of the first lessons an inbetweener learns is that a face turn shouldn’t have a direct middle in it. The middle drawing (#3 here) shouldn’t be straight on; it should favor, slightly, one side or the other.

Despite the simple drawings of Mickey, Ub Iwerks seemed to understand this instinctively. He didn’t really get lessons from anyone. As a matter of fact, he was creating the rules. This comes close to being straight on, but the mouth gives it away. The face is facing screen left.

Another simple inbetween lesson is to offset the inbetween (usually an animator or good assistant will set this up for the inbetweener.)

Another simple inbetween lesson is to offset the inbetween (usually an animator or good assistant will set this up for the inbetweener.)

Here Mickey is standing upright on #1 and he’s upright on #5. Drawing #3 has him with knees bent, beating in tempo to the sound. Even though this is from the first sound cartoon, done in 1928, the offset rule is in effect.

I think it’s pretty clear that some sophistication has entered the animation that Iwerks was drawing. This same sophistication isn’t in other animator’s work.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Add to this the fact that Iwerks was probably the fastest producing animator, and you probably have good reason for knowing he was the genius behind Disney.

This, of course, didn’t remain that way. After Iwerks left, leaving behind enough animators trained by him, their work developed exponentially. Better artists were entering the studio and bringing their talents to the work, and they started making a serious attempt to improve the work.

Iwerks stopped animating and stopped trying to improve the character animation. Instead, he tried to improve the camera – actually developing the mulitplane camera in his own studio. Animation, under Iwerks, didn’t develop.

The book by John Kenworthy, The Hand Behind The Mouse, gives some solid information that wasn’t previously published and puts a lot of material into perspective. Someday we’ll get another voice on this great subject with more critical insight.

on 18 Oct 2006 at 1:24 pm 1.Stephen Worth said …

Grim Natwick told me that Gregory LaCava used a rudimentary storyboard system at Hearst. He would draw the whole story as a comic strip, then number the scenes and cut up the comic, handing panels to each animator to animate. This was almost a decade earlier than Disney’s “invention” of the storyboard.

Iwerks was a great innovator and animator, but it’s hard to see why Mickey was such an success in the early years when you compare the 1929-1930 Mickey cartoons to the Fleischer cartoons of the same period. Fleischer’s techniques for animating to music were light years ahead of Disney’s at the time and the cartoons are more cinematically sophisticated.

The Fleischers addressed the problems of animating to a musical beat in the silent era with the Bouncing Ball cartoons, and later with the first seven sound cartoons they produced using the DeForest Phonofilm process, three years before Steamboat Willie was made. The superiority of the Fleischer cartoons is also due in large part to the imaginative and expressive animation of Grim Natwick. Even Iwerks himself recognized this, handing over the direction of the films at his own studio to Grim on the Flip, Willie Whopper and Comicolor shorts.

The one who is truly unappreciated is Bill Nolan. Natwick spoke very highly of his abilities in the time they worked together at Hearst, and the early Lantz Oswald cartoons are MUCH funnier than any of Disney’s Ozzie cartoons. I’d like to know more about Bill Nolan.

See ya

Steve

on 18 Oct 2006 at 2:42 pm 2.Michael said …

When Grim Natwick went out to LA, he didn’t seek out Bill Nolan. He sought out the one he thought was the best in the businees – Ub Iwerks. And he took a pay cut to do it (Disney had offered him much larger salary.) All I know about Bill Nolan was that he was extremely fast. None of the animation I’ve seen of his stands out from anything else at the time, yet it can’t be denied that Nolan was one of the giants.

on 19 Oct 2006 at 1:13 am 3.Stephen Worth said …

Disney’s offer to Grim is here.

See ya

Steve

on 20 Oct 2006 at 4:39 pm 4.Dan said …

Hey Steve, goo job parroting exactly what John K. always says. And by the way, the storyboard technique, and the comic strip techniques of making animation stories are different. Anyway, Ub Iwerks animation is leagues better than the crude animation of Grim Natwick (many of the Ub Iwerks cartoons of the thirties are unwatchable because of his presence.) in my opinion.

on 20 Oct 2006 at 4:53 pm 5.Michael said …

Boy, are you off the mark, in my opinion. By the time Natwick was working for Iwerks, the boss had stopped growing as an animator. Natwick continued to develop and produced miles of brillliant animation (just take a look at True Blue Sue in Rooty Toot Toot; there’s no way Iwerks could ever have come near animating that!)

Oh well, to each their own.

on 21 Oct 2006 at 2:33 pm 6.Stephen Worth said …

Hey Dan, goo (sic) job answering my supported argument with a completely subjective blanket dismissal.

By the way, I have copies of a section of storyboard by Gregory LaCava from a Hearst Krazy Kat cartoon, and it sure looks like a storyboard to me. The staging, action and scene cuts are all drawn out. It even has indications where iris ins and dissolves go.

As for parroting… Guess who it was who sat down with John K over ten years ago and showed him Grim’s Bouncing Ball cartoons and shared his theories on Grim’s importance and the general superiority of the Fleischer cartoons in the early 30s? I’ll give you three guesses and the first two don’t count.

See ya

Steve

on 24 Oct 2006 at 12:09 pm 7.John Kenworthy said …

I think the reason that Mickey was so successful compared to the contemporaneous Fleischer’s product is because of some oddity in the design of the character. There is no question that Fleischers were light years ahead in animation – that’s the reason why Ub hired Grim, Culhane, Berny Wolf and Al Eugster to his studio later on. He wanted the very best and he got them. No question that he thought the world of Grim in particular (as Grim did Ub in return.) And you can see a definite leap in quality the moment Grim arrived.

But there’s no denying that doggoned Mouse had something special in his early iteration. Perhaps all those psychobabblists are right when they claim that Mickey appeals on a preternatural level (Chuck Jones always talked about the universality of the Mouse’s circular design, and the eye size and all those kid-appeal aspects). I don’t know. I do know that Mickey is very appealing in those early shorts in a way that he isn’t later on – circles or not. Likewise, Betty and KoKo are great designs and animated wonderfully – and stylish as heck, (Betty certainly has lasted the years as an icon) And like Steve says – they were very cinematically sophisticated – but somehow they don’t have that childish appeal as does early Mickey. They appeal more to a more mature, intellectual (for lack of a better word) crowd. Even Superman and Popeye have different aesthetics to them. They are not as innately warm or as earth-bound. There is a bit of Brechtian distance to them. Mickey I think in those early shorts appeals to almost a pre-intellect of sorts.

But that being said, Flip the Frog was pre-intellectual in the same way as Mickey early on and was not at all appealing as a character or design. When Grim changed him later on, he moved more to the Fleischer-style of comedy and character (as the Comicolors moved toward Fleischer-style sophistication thanks to Grim), but never attained warmth. He (and stablemate Willie Whopper) would never have had that insane allure as did Mickey from those early fanatical days.

Just my two bits worth…

on 24 Oct 2006 at 12:51 pm 8.Michael said …

John, your two bits were worth much more. Nothing I can disagree with. I do think that Iwerks had already tired of animation by the time he’d started his own studio, and was more interested in the process.

I think it was much like the story in your book about Iwerks getting hooked on bowling until he hit a 300 score, then he never bowled again. His mind was faster than his hands and couldn’t be entertained by merely animating/acting.

on 26 Oct 2006 at 11:57 pm 9.Thad Komorowski said …

I think Irv Spence had more to do with the appealing look at Iwerks than Grim did. Just my two cents.

THAD

on 27 Oct 2006 at 7:48 am 10.Michael said …

Thad, have you read about Iwerks’ studio (see John Kenworthy’s book – or watch the documentary), or are you just making that decision off the top of your head because you know a lot about and like Irv Spence?

There’s just too much speculation and opinion going on about history and facts. It’s one of the primary problems with the Internet. I’m as guilty as anyone. I have to learn to temper my “facts.”

on 27 Oct 2006 at 4:16 pm 11.Thad Komorowski said …

Hmm, I don’t know a lot about the Iwerks studio, I was just told by a few animators that Spence did all the scenes that I thought were the best looking.

Quite frankly I’m not a big fan of Grim. His animation on the Lantz cartoons looks like something that he’d have done for Fleischer or Iwerks a decade earlier – old school drawing in the worst way and very sloppy animation. It looks like he just doesn’t care and I resent his poor animation despoiling the otherwise excellent Lantz cartoons (especially Abou Ben Boogie).

THAD

on 27 Oct 2006 at 4:23 pm 12.Thad Komorowski said …

To follow up on Spence, a lot of his animation ( specifically in the phrasing of actions) for Avery at Warners in the late 30s looks similar to animation in the later Flip the Frog shorts (Room Runners especially).

THAD

on 27 Oct 2006 at 6:46 pm 13.dan said …

A storyboard is posted on a wall. A comic book is not. Is whatever you are describing a comic book or a storyboard. Even if Disney did not invent the storyboard, they put it to better use than Mr. LaCava did. And I don’t care if Ub Iwerks liked Grim Natwick’s animation. The Flip teh Frog, Willie Whopper and ComiColor cartoons are horrible.

on 28 Oct 2006 at 2:51 pm 14.dan said …

The assertion that the Fleischer’s animation was “light years” ahead of Disney’s is pure nonsense. Fleischer’s, to my knowledge, did not even adopt cel animation until 1930. Disney pioneered cel animation in the early twenties. The Mickey cartoons of twenty eight do look relatively crude, but the animation from Fleischer’s at that time looked much more primitive. If you compare Disney’s 1929 cartoon Jungle Rythm, or Mickey’s Choo-Choo to the Fleischer cartoons of the same era, Disney is leaps ahead. When Natwick joined Fleischer’s in 1930 the quality became better, but Disney’s was much better, as it improved year by year.

on 30 Oct 2006 at 12:59 pm 15.Michael said …

Hi Dan:

The fact that you think the Fleischer films hadn’t adapted to cel animation prior to 1930, shows that you haven’t even seen the films that you’re criticizing. Since the Fleischers worked for J.R.Bray, they were obviously using cels – probably earlier than Disney.

Though I’m not the biggest fan of the Fleischer work and realize how advance Disney started getting after 1930, I’m not about to compare, criticize or attack either of them.

I suggest you see films that you’d like to criticize.

Thanks.

on 03 May 2010 at 2:18 am 16.Anonymous said …

Animation Cel patented by Earl Hurd and John Bray in 1914.

on 24 Oct 2024 at 11:24 pm 17.Mejo Kallamthanam said …

“Quite frankly I’m not a big fan of Grim. His animation on the Lantz cartoons looks like something that he’d have done for Fleischer or Iwerks a decade earlier – old school drawing in the worst way and very sloppy animation. It looks like he just doesn’t care and I resent his poor animation despoiling the otherwise excellent Lantz cartoons (especially Abou Ben Boogie).”

I like Grim but to each his own (even if you are a bit too harsh and mean on your opinions)