Action Analysis &Animation &Books &Commentary &Disney 20 May 2013 05:54 am

Illusions – of Life

I started discussing some of the thoughts put forward in The Illusion of Life, the book by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. I had some major problems with some of the discrepancies in that book. Here’s the second, a continuation of that post.

It cannot be doubted that without the speedy roughs, there would never have been the brilliance of Tytla‘s best work or Ferguson’s great comic animation.

It cannot be doubted that without the speedy roughs, there would never have been the brilliance of Tytla‘s best work or Ferguson’s great comic animation.

- On page 39 of the book, we read, “Walt introduced two procedures that enabled the animators to begin improving. First, they could freely shoot tests of their drawings and quickly see film of what they had drawn, and, second, they each had an assistant learning the business who was expected to finish off the detail in each drawing. Walt was quick to recognize that there was more vitality and imagination and strength in scenes animated in a rough fashion, and he asked all animators to work more loosely. The assistant would ‘clean up’ these drawings that looked so sloppy, refining

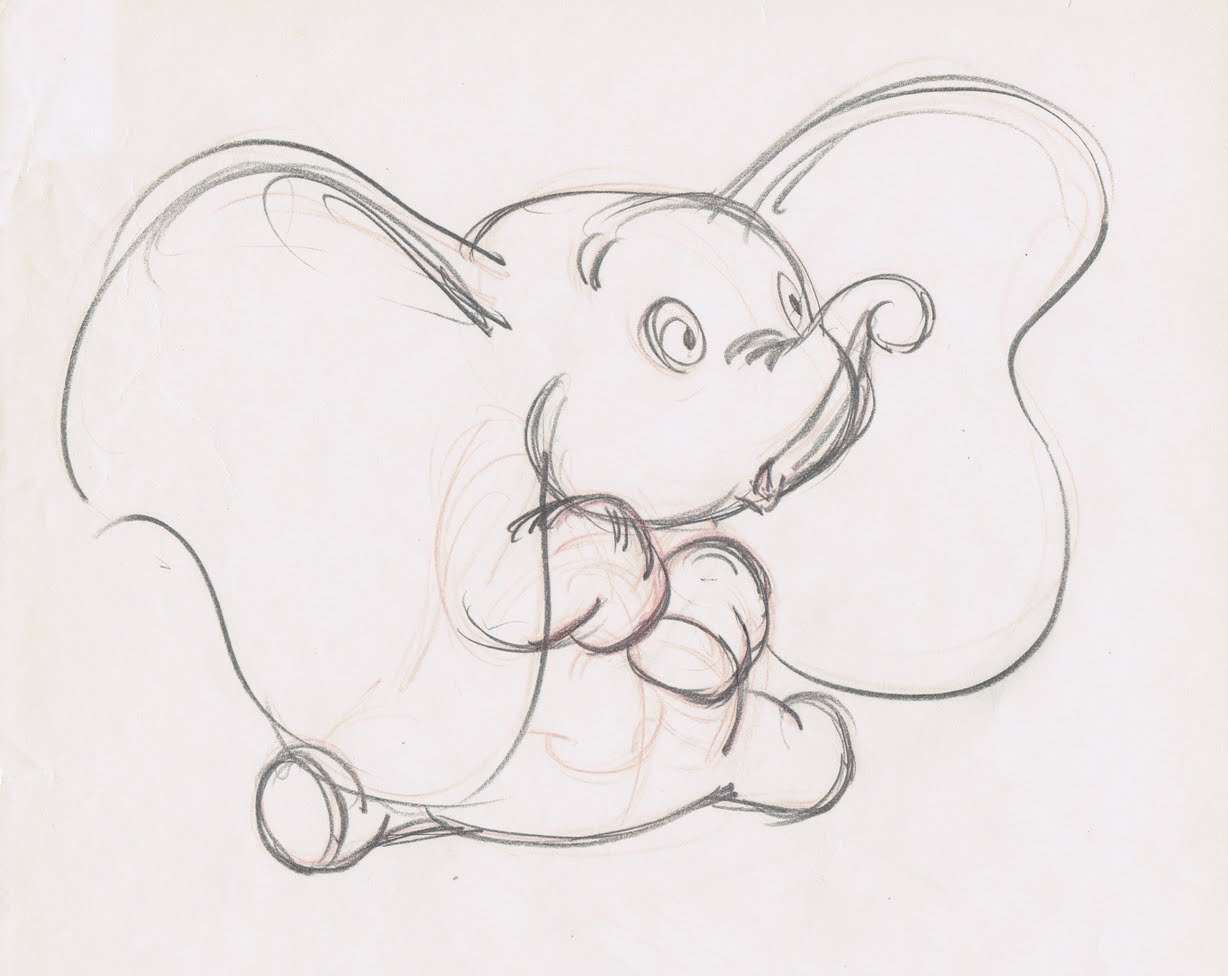

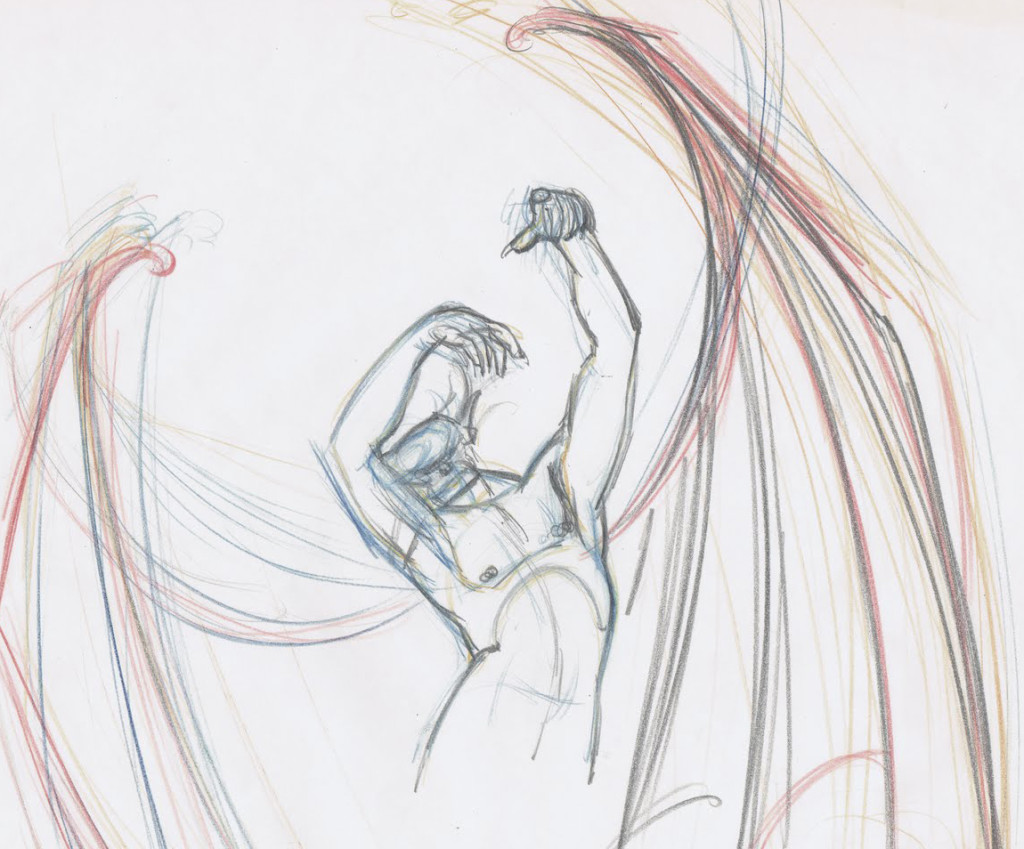

them to a single line that could be traced by the inkers onto celluloid. The assistants became known as ‘clean-up men,’ and the animators developed one innovation after the other, achieving effects on the screen that no one had thought possible. In some cases, the drawings were so rough it was difficult to find any cartoon figure inside the tangled swirl of lines, and the men who made a duck or a dog out of smudges and scratches had to have a very special type of knowledge.

them to a single line that could be traced by the inkers onto celluloid. The assistants became known as ‘clean-up men,’ and the animators developed one innovation after the other, achieving effects on the screen that no one had thought possible. In some cases, the drawings were so rough it was difficult to find any cartoon figure inside the tangled swirl of lines, and the men who made a duck or a dog out of smudges and scratches had to have a very special type of knowledge.

Shooting tests of scenes while they were still in the rough enabled the animators to check what they had done before showing it to anyone. Any part that was way off could be corrected quickly and

shot again. This encouraged experimentation, exploration, and imagination, quickly promoting a closer bond among the animators.

shot again. This encouraged experimentation, exploration, and imagination, quickly promoting a closer bond among the animators.

- Yet on page 229 the authors turn to side with management when they suggest that “. . . a new procedure called ‘Touch-up’ was instigated. It asked that the animator draw slowly and carefully enough so that the assistant need only touch up the drawings here and there to make them ready for the Ink and Paint Department. By this time all of our animators had become more skillful and were able to adjust to the new idea without noticeable damage to the product. Top quality clean up work is needed on only a handful of scenes in any sequence, and a great variety_____________Three Tytla ruffs

of shortcuts can be used on the balance

to make them acceptable.”

In short, this means that the older nine men and some of the other more seasoned veterans could work clean because they were already brilliant at the animation thing. Whereas Walt had demanded that animators, in the 1930s, work rough so as to keep the animation as loose and free and alive as possible.

In short, this means that the older nine men and some of the other more seasoned veterans could work clean because they were already brilliant at the animation thing. Whereas Walt had demanded that animators, in the 1930s, work rough so as to keep the animation as loose and free and alive as possible.

It also veered toward Milt Kahl’s pleasure at seeing hos own lines used in the newly developed Xerox outline in the final ink & paint. If the assistants would indiscriminately erase only some of the animators’ lines leaving many other key lines (including, at times, construction lines for the face and body parts). Kahl’s ego wanting to see his own beautiful line meant superseding color inking – as had been done in the past._______A relatively clean drawing by Norm Ferguson

Using this new procedure would mean a need for fewer clean-up artists who could work faster and with fewer problems, thus speeding up the footage rates. It also depended on the animators, such as Thomas and Johnston who worked fast enough, that the footage rates were now closer to what they could turn out.

One wonders if this new found speed would also cut into the imagination of the scenes these men animated. (By they way, I use the term “men” because Johnston and Thomas do not once in this book consider the possibility of a female animator. It’s always”men” or “he” or “him”. Old prejudices die hard; though I suspect the two had no problem with the idea of a female animator. In fact they always bowed low in front of Tissa and her abilities. And I’m certain they were not patronizing her in any way.

One wonders if a chink in the armor hadn’t developed then and there in the animation production. Younger people would do all they could to work clean, thus handicaping the animation they turned out.

As a long-time assistant, I know that my animation has been tight to the extreme, annd more than once Jack Shnerk advised me to start working rough when I animated. However, as management (I am the boss of my own company and controller of my own films), I sought to turn out the largest output and eliminated any assistant or inbetween working on my material. I sacrificed good animation for speed and production. It has not only hurt my work but my films, and I know it.

on 20 May 2013 at 7:42 am 1.Bill Benzon said …

“…and the men who made a duck or a dog out of smudges and scratches had to have a very special type of knowledge.”

I should think so. And, it’s one thing to disambiguate a single drawing. But, of course, the assistants had to do that to a closely matched set of drawings. If it’s not done right you’ll end of with a sequence of drawings that look good individually but which don’t flow smoothly when projected at speed.

on 20 May 2013 at 1:13 pm 2.Liim Lsan said …

Actually, the “touch-up” policy was instituted almost correlatively with the enroachment of Xerox Inking. You see,

Eric Larson was the first total clean-up man in the business (under Ham Luske) and management was livid at how he handled the cleanup department when he was directing on ‘Sleeping Beauty.’ His cleanup department completed the cleanups of Aurora’s Forest Interlude scene at a rate of ONE DRAWING A DAY. That’s how perfectionist he was.

On the later part of Sleeping Beauty, they instituted “touch-up” in a desperate attempt for footage.

When Xerox enroached, it was even more encouraged for the animators to draw clean – and the studio couldn’t afford to hire anyone, so there were no new recruits trying to animate in ‘ligne claire.’

What strikes me, personally, reading “Illusion of Life” (did this occur to you?) is that the animators lived under a rock. You see quotes like “Undoubtebly the character animation is the thing that attracts the audience to see the film,” revealing how they didn’t care about what the audience was thinking. At no point are they inspired by a bit of camerawork or music or personality from ANOTHER film – and the constant insinuation that the Disney films are the only worthwhile films of all time, and that no one else actually achieved personality animation, and that no one could do good work outside of Disney, etc. get wearying fast.

Remember, when Thomas and Johnston left the studio (1978) to write the book, women still weren’t even permitted to wear PANTS at the studio. It was a relic of a bygone age by then … the masculine infinitive object in English was so widely used at the time that I’m sure they give no thought to it!

Mike, if you truly reflexively draw so clean, that’d actually explain some of the atmosphere of the films – it certainly fits your graphic sense. (“Whitewash” and “The Dancing Frog” were really successful in this – it looks as if your graphic sense determines the form, and not just the volition. It preserves that “handmade” aesthetic you champion so well, and you shouldn’t worry that it made the films bad. Whether they would have been better or not with looser rendering, though, you would know better than anyone else. (Incidentally, with these ‘clean’ lines, did you draw from the wrist, finger, elbow, or shoulder? It’d certainly have an impact, and your work leaves one curious.)

on 20 May 2013 at 1:28 pm 3.Evon Porter said …

“…I sought to turn out the largest output and eliminated any assistant or inbetween working on my material. I sacrificed good animation for speed and production. It has not only hurt my work but my films, and I know it.”

If I’m reading that right, you’re saying your work suffered by not using the production methods developed by Disney and the 9 old men. I think your not giving yourself enough credit. You did what your instincts told you to do. You animated.

According to Bakshi, Jim Tyer did the most footage at TerryToons per week, straight ahead, by himself, no roughs. To me you were working in the best traditions of Iwerks, Tyer and Richard Williams. They animated.

It’s high time to call Disney and 9 old men out on some of their b.s. They were brilliant, but can they have it both ways? They crow about the animation production methods they developed that decreased the amounts of completed drawings the lead animators had to do, but they don’t want to lose any credit for the completed animation. (how much of the animation did they actually do with all those assistants doing the cleanup and inbetweeners doing the majority of the drawings? Were they animators that animated? Or were they directors that could draw really good?

on 21 May 2013 at 9:48 am 4.David Nethery said …

“At no point are they inspired by a bit of camerawork or music or personality from ANOTHER film.”

That isn’t accurate , if you’re talking about the Disney studio in general, especially during the period of rapid expansion from 1932 – 1941 . By all accounts , the studio’s creative staff screened a steady stream of live-action films from various studios (including foreign films). And of course there were the detailed Action Analysis classes studying the work of Chaplin, Keaton, and other great pantomime performers.

On the other hand, if what you meant by that statement is that Thomas and Johnston make almost no reference to other animated films outside of Disney and don’t seem willing to admit that any worthwhile animation technique was developed at other animation studios outside of Disney’s , then that is true. In that sense it does seem as if they lived in a bit of a bubble.

on 21 May 2013 at 10:36 am 5.David Nethery said …

“It’s high time to call Disney and 9 old men out on some of their b.s. They were brilliant, but can they have it both ways? They crow about the animation production methods they developed that decreased the amounts of completed drawings the lead animators had to do, but they don’t want to lose any credit for the completed animation.

(how much of the animation did they actually do with all those assistants doing the cleanup and inbetweeners doing the majority of the drawings.”

Well, how about I call you out on your B.S. ?

Look, I was was an assistant animator for years, so believe me, I’m all for giving due credit to the great assistant animators from the Golden Age films for their role in the success of the films (which Thomas and Johnston briefly acknowledge — though only two directly by name , Dale Oliver and Walt Stanchfield — on page 228- 229 , and the aforementioned comment from page 39 about “… the men who made a duck or a dog out of smudges and scratches had to have a very special type of knowledge.â€) , however I think your statement reveals that you know very little about the work of these great animators or indeed how ‘Hollywood’ animation in general was made (at other studios, too, not just Disney) if you think that merely because the inbetweener does a larger percentage (sometimes, not always) of the drawings in the finished scene that means you can then seriously question how much of the animation did the credited animator actually contribute to the scene. (Really ?) If you really think that you have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s a collaborative effort for sure , no one who has worked in the business denies that , and in the “Golden Age” there’s no doubt that screen credits were doled out rather too sparingly, but if you’re going to try to pin that on Disney or the ‘Nine Old Men’ (as part of “their b.s.” ) then you’ve got to lay it on the directors and animators at all the other studios who did not give screen credit to the assistants , the inbetweeners, the inkers, the painters and the dozens/hundreds of other people who contribute to making mainstream studio animated films.

on 21 May 2013 at 9:25 pm 6.Floyd Norman said …

As one of the clean-up artists on Walt Disney’s Sword in the Stone in the sixties I can assure you that the animators didn’t work all that clean. Sure, when I worked with Stan Green on Milt Kahl’s stuff the directing animator was an exception. But, that was just Milt.

Frank Thomas’ animation remained rougher than hell, but brilliant as always. His stuff was still a bitch to follow up. I know from first hand experience and I got my ass chewed out because of it. Still, I have only the highest respect for these guys even though “Illusion of Life” spends much too much time on the later years at Disney doing stuff that was not always their best.

on 22 May 2013 at 3:22 am 7.Michael said …

Frank’s work on Sword in the Stone has to be right up there with his best. The squirrel sequences are just brilliant despite the fact that he turned out a million feet of animation a week no doubt leaving a lot in the hands of brilliant guys like you, Floyd.