Animation &Animation Artifacts &Commentary 01 May 2013 06:52 am

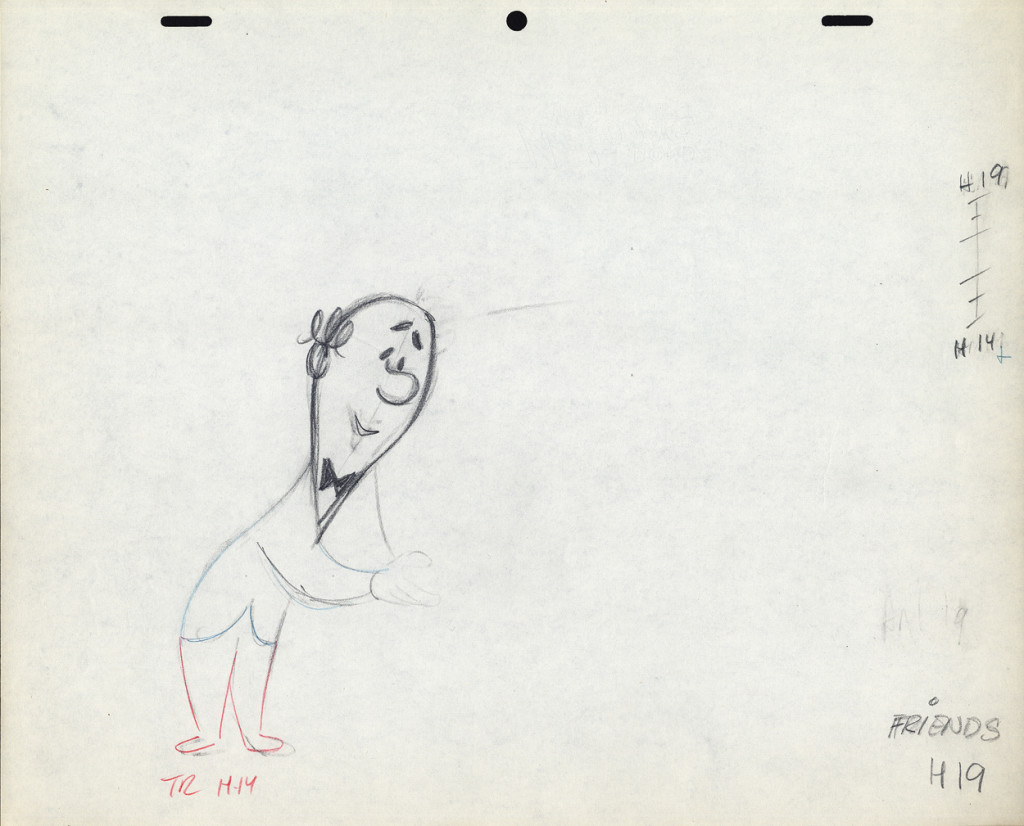

Piels Bros Commercial Animation Dwngs

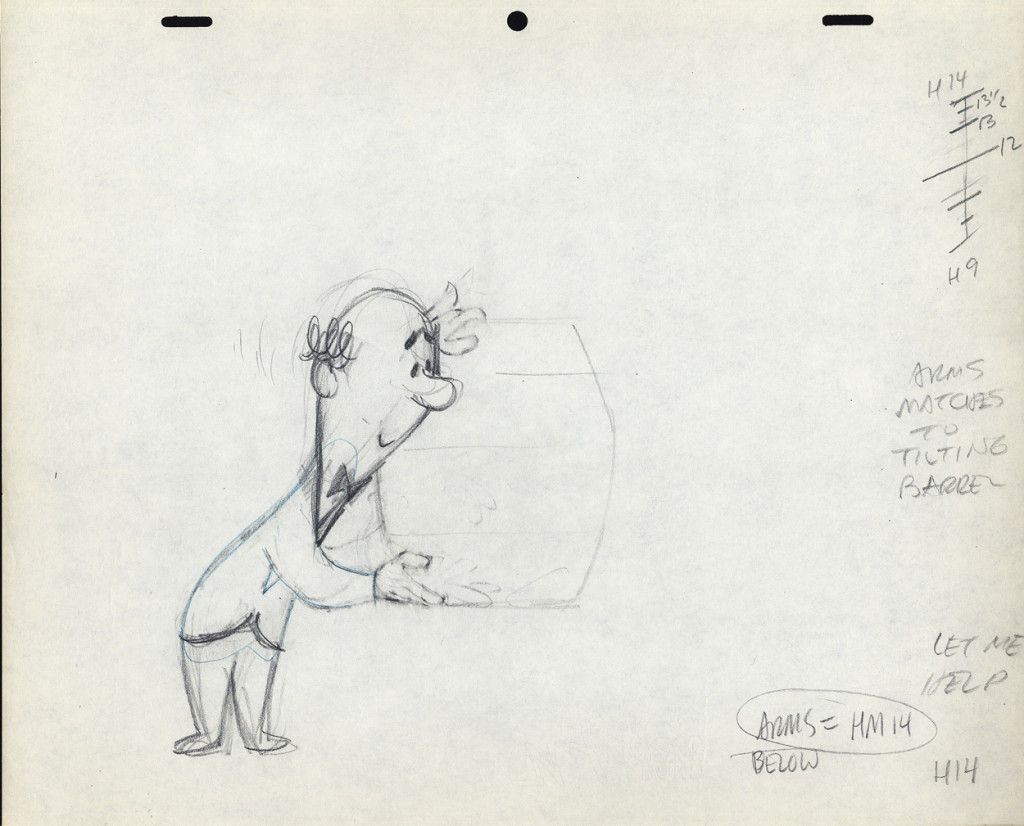

Here’s the last of the three posts I’ve been able to cull from the drawings left behind in Vince Cafarelli‘s things. The 60 second spot was animated by Lu Guarnier and clean-up and assisting was by Vinnie.

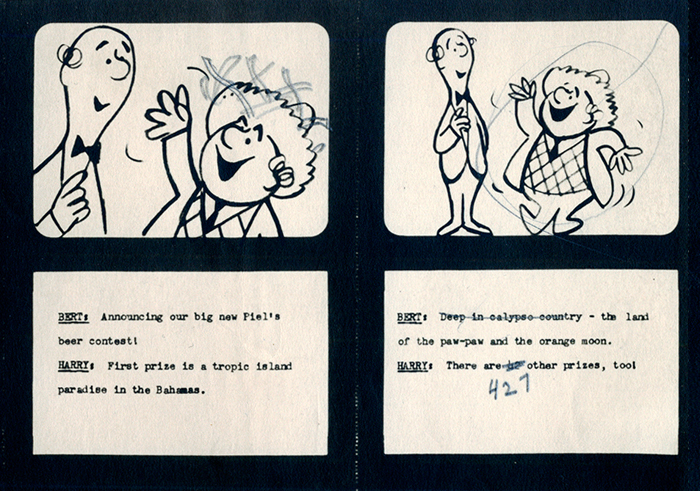

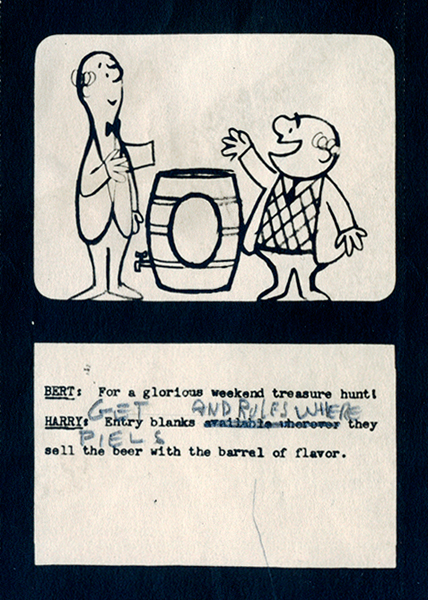

Within this post there are drawings from two separate scenes. If you look at the storyboard (I’d posted the entire board in another post, but I’ve pulled the particular frames from the board to show again here), you can see what it is the characters are saying. I don’t have all the drawings for these two scenes; just those I’ve posted.

I’m also going to use these drawings of Lu’s to write about his style of animation. I was taught from the start that this was completely done in an incorrect way. I don’t mean to say something negative about a good animator, but it is a lesson that should be learned for those who are going through the journeyman system of animation.

Right from the get-go I had some difficulty assisting Lu’s scenes. He started in the old days (early-mid Thirties) at Warner Bros, in Clampett’s unit, and moved from there to the Signal Corps (Army); then to New York working at a few studios before landing at UPA’s commercial studio. After that, he free lanced most of his career, as had so many of the other New York animators. They’d work for six months to a year at one studio then would move on to another.

Right from the get-go I had some difficulty assisting Lu’s scenes. He started in the old days (early-mid Thirties) at Warner Bros, in Clampett’s unit, and moved from there to the Signal Corps (Army); then to New York working at a few studios before landing at UPA’s commercial studio. After that, he free lanced most of his career, as had so many of the other New York animators. They’d work for six months to a year at one studio then would move on to another.

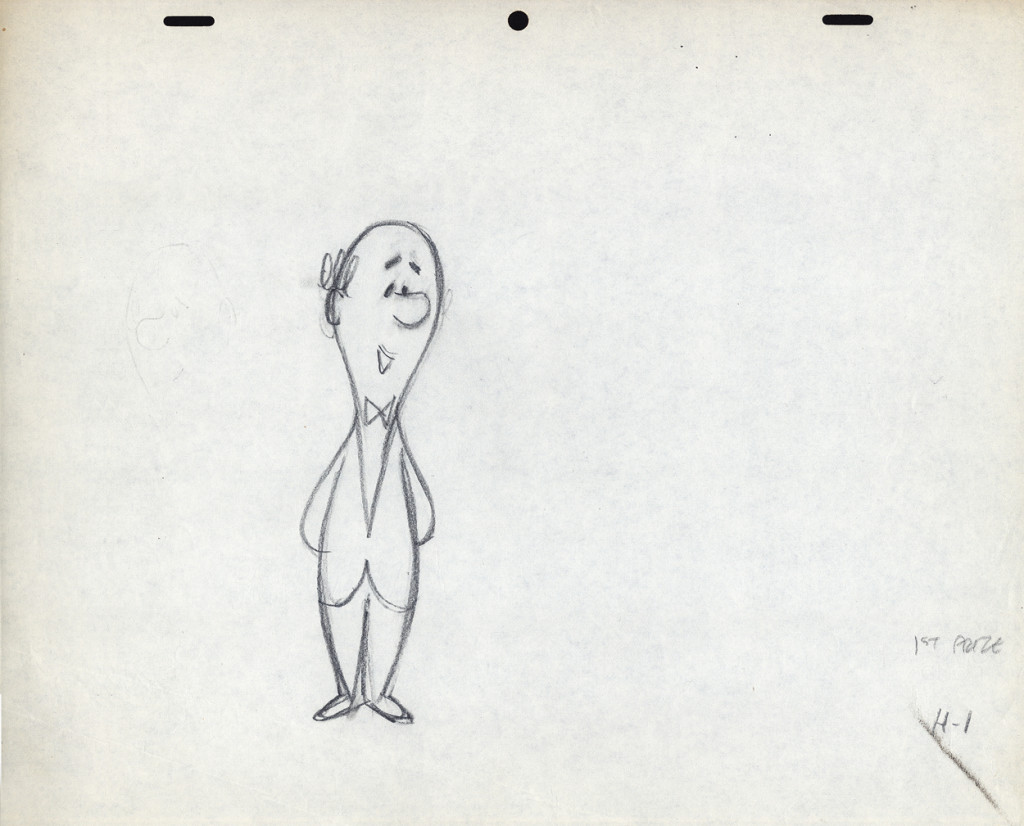

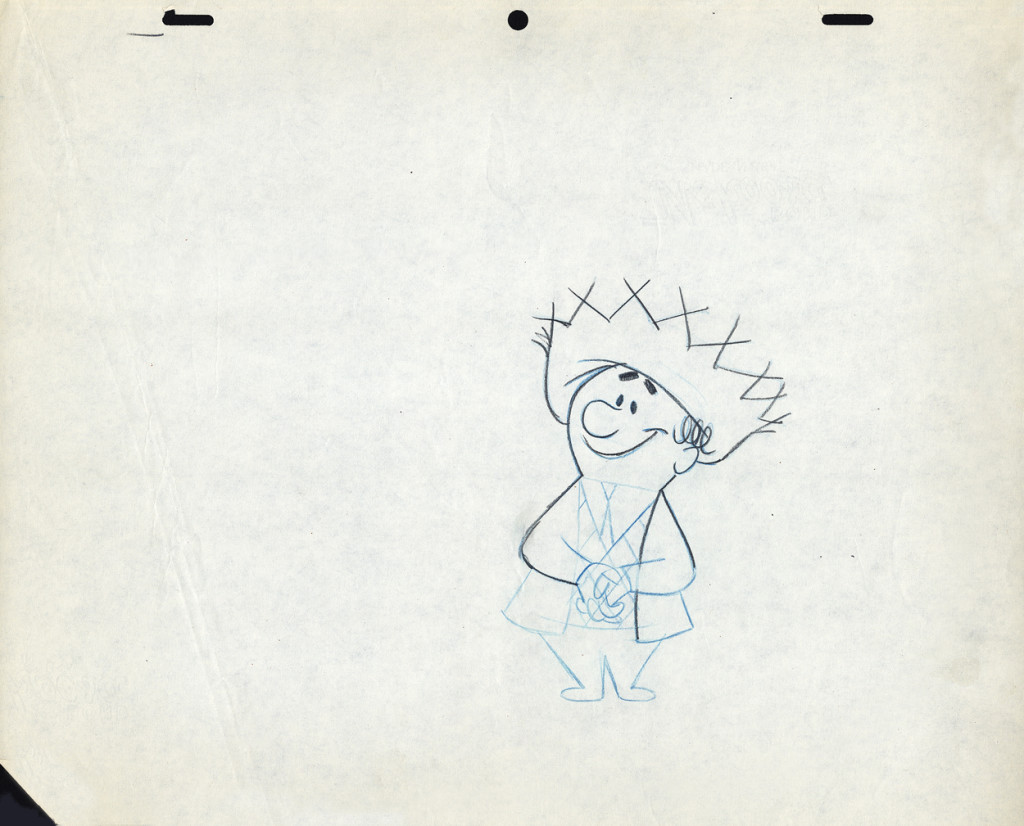

I suspect the problems in Lu’s animation all generated from the training he’d gotten at WB. Lu worked in a very rough style. No problem there. An animator should work rough. These drawings posted aren’t particularly rough, but in his later years (when I knew him) there was hardly a line you could aim for in doing the clean-up. His style was done in small sketchy dashes that molded the character. Rarely was it on model, and always it was done with a dark, soft leaded pencil. There were others who worked rougher, Jack Schnerk was one, but Lu’s drawing was usually harder to clean up.

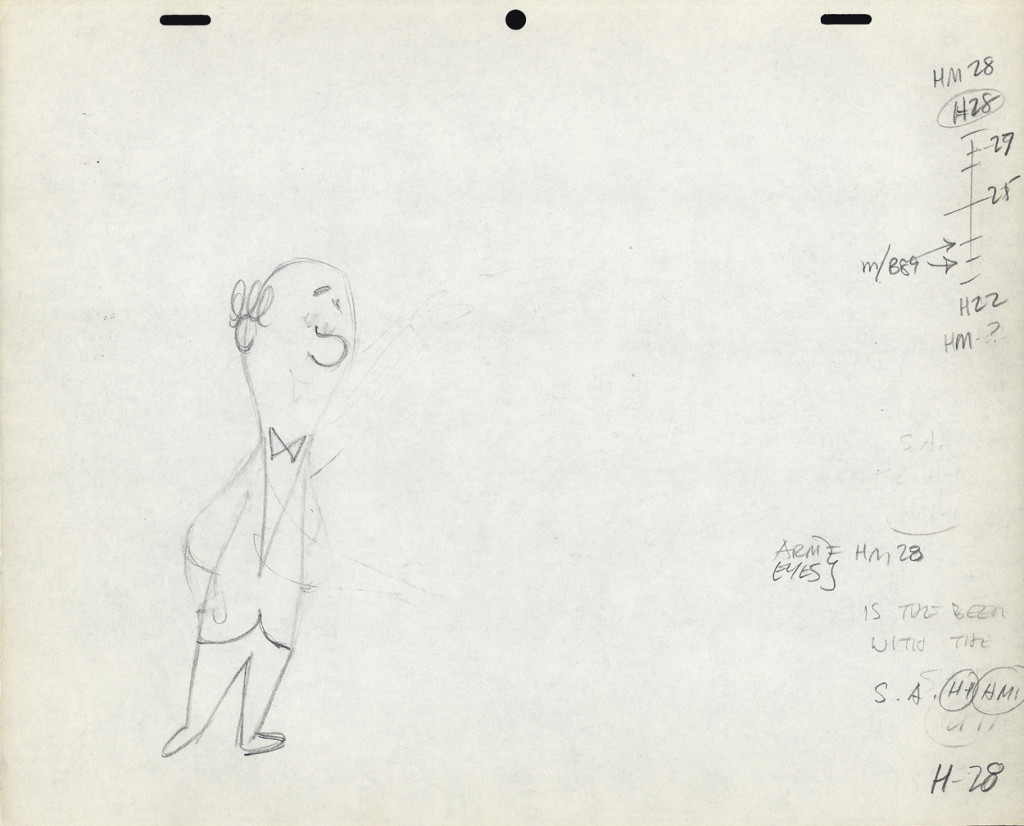

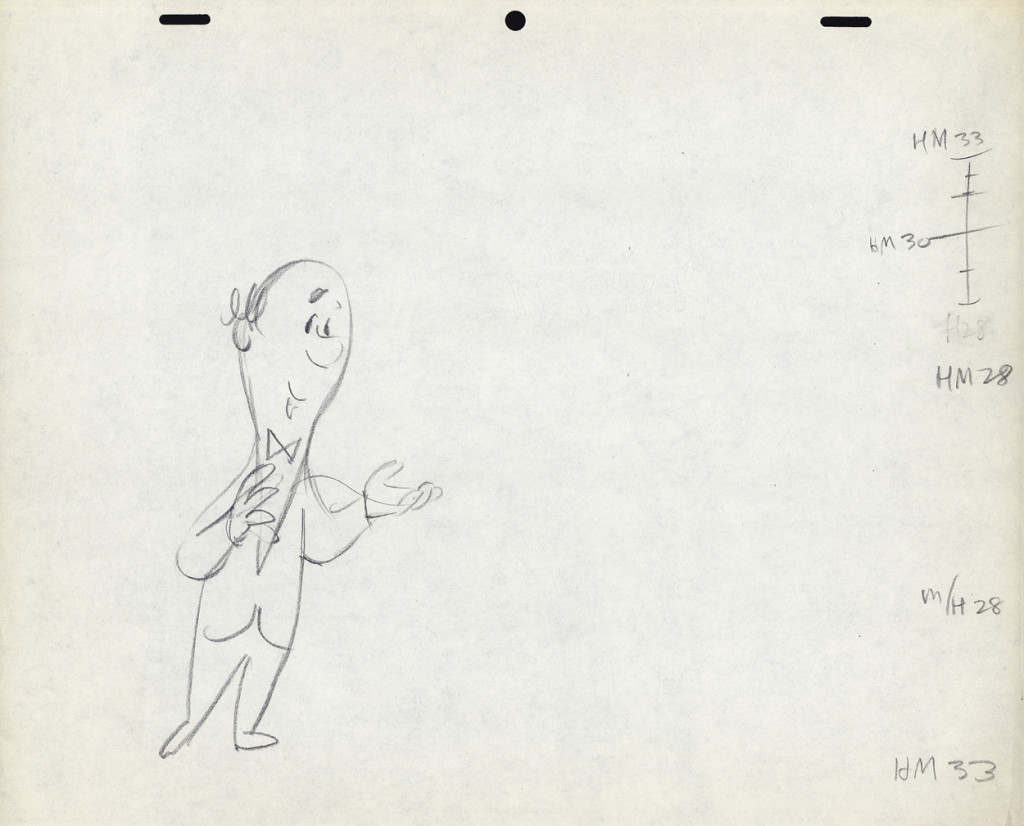

There was a rule that came out of the Disney studio, and, as both an animator and an assistant, I’ve followed it closely. When doing the breakdown charts (those ladders to the right of the drawing) all inbetween positions had to be exactly half way between drawing “A” and drawing “B”. If the animation called for it to be 1/4 of the way, you’d indicate that half-way mark then indicate your 1/4. If a drawing had to be closer or farther away – say 1/3 or 1/5th of the way – the animator should do it himself. This, as I learned it, was the law of the land. However, Lu would rarely adhere to it, and an assistant’s work became more complicated. The work was too easily hurt by a not-great inbetweener. I’ll point out an example of Lu’s breaking this rule as we come to it).

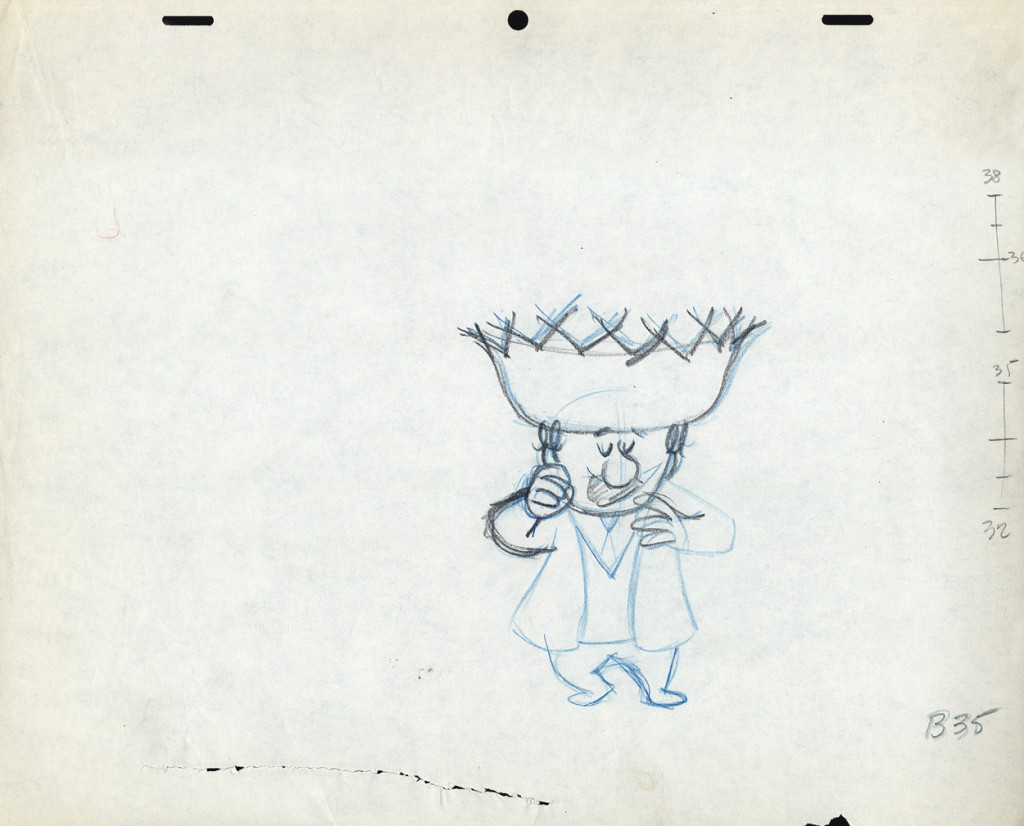

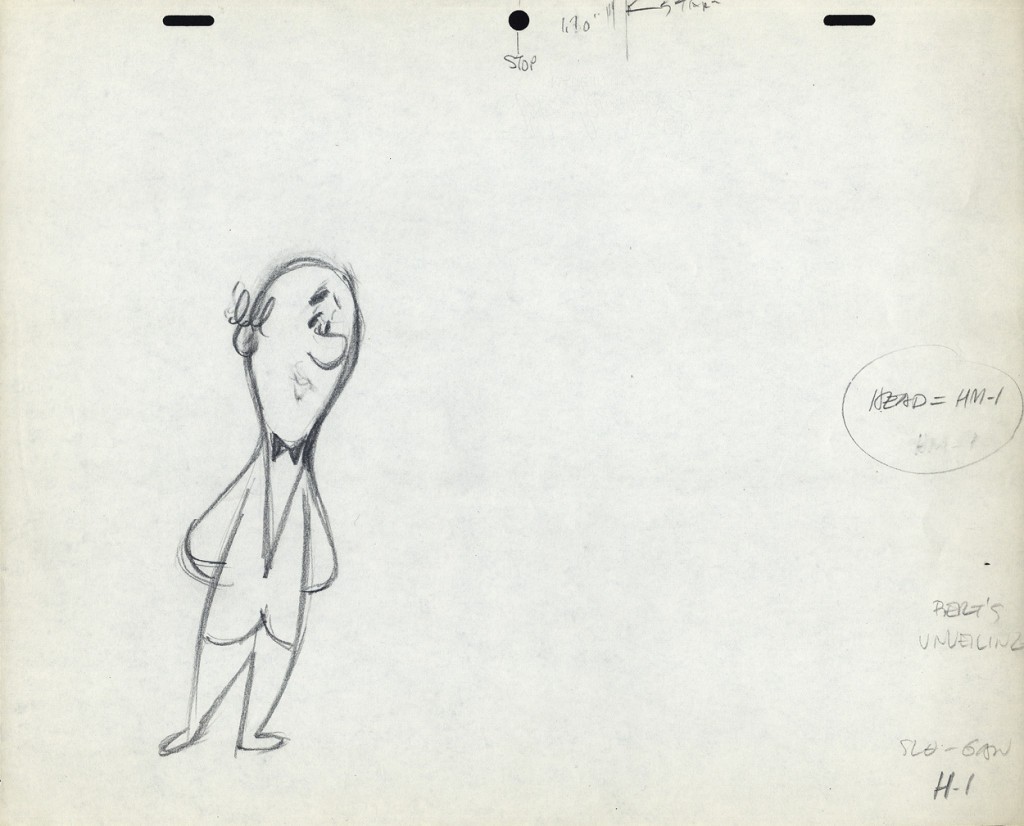

B35

B35

These ladders are done correctly, per the Disney system.

#34 is half way between #32 & #35;

#33 is half way between #32 & #34.

#36 is half way between #35 & #38;

#37 (the 1/4 mark) is half way between #36 & #38.

However, Grim Natwick told me

- demanded of me –

that all ladders should appear on the lower numbered drawing.

The ladder here should be on drawing #32 for all art

going into the upcoming extreme, #38.

Lu never followed this rule, which means the

assistant generally had to search for the chart.

The Second scene

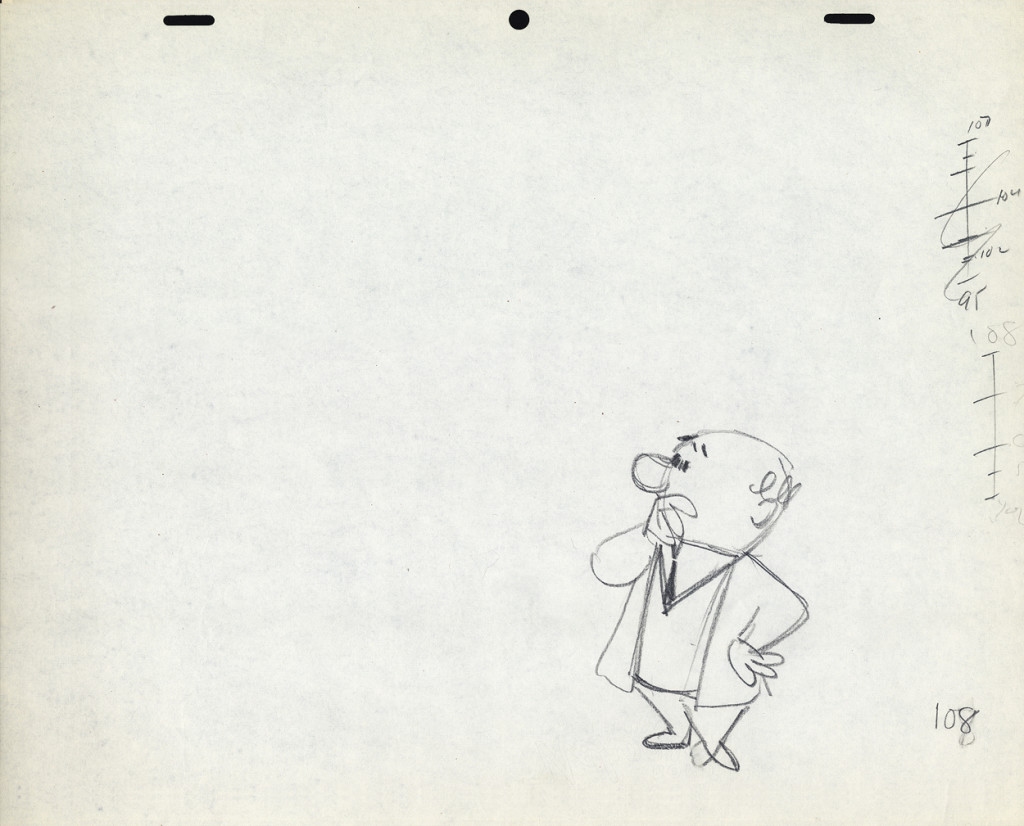

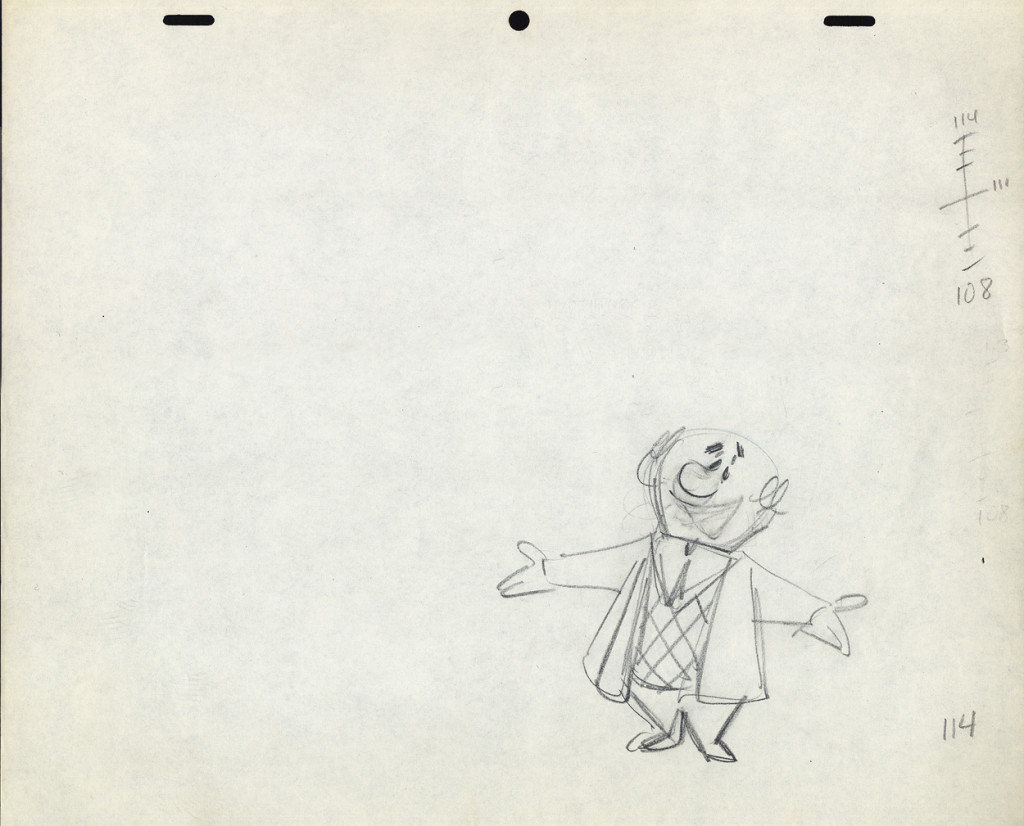

B108

B108

This ladder is typical of Lu’s animation.

It would seem that #106 is 1/3 of the way between #108

and #105 is half way between #106 and #109.

and it also looks like #107 is 2/3 of the way between #108 and #109.

Because the numbers come on the last of the extremes, here,

more confusion is allowed to settle in.

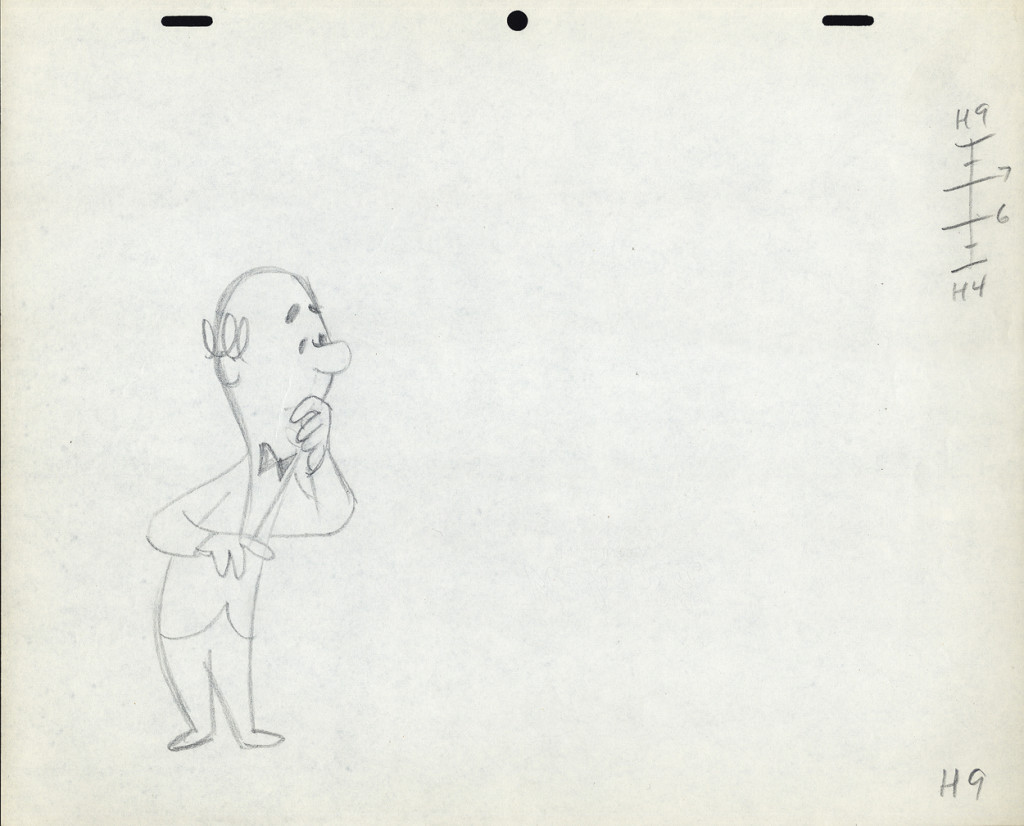

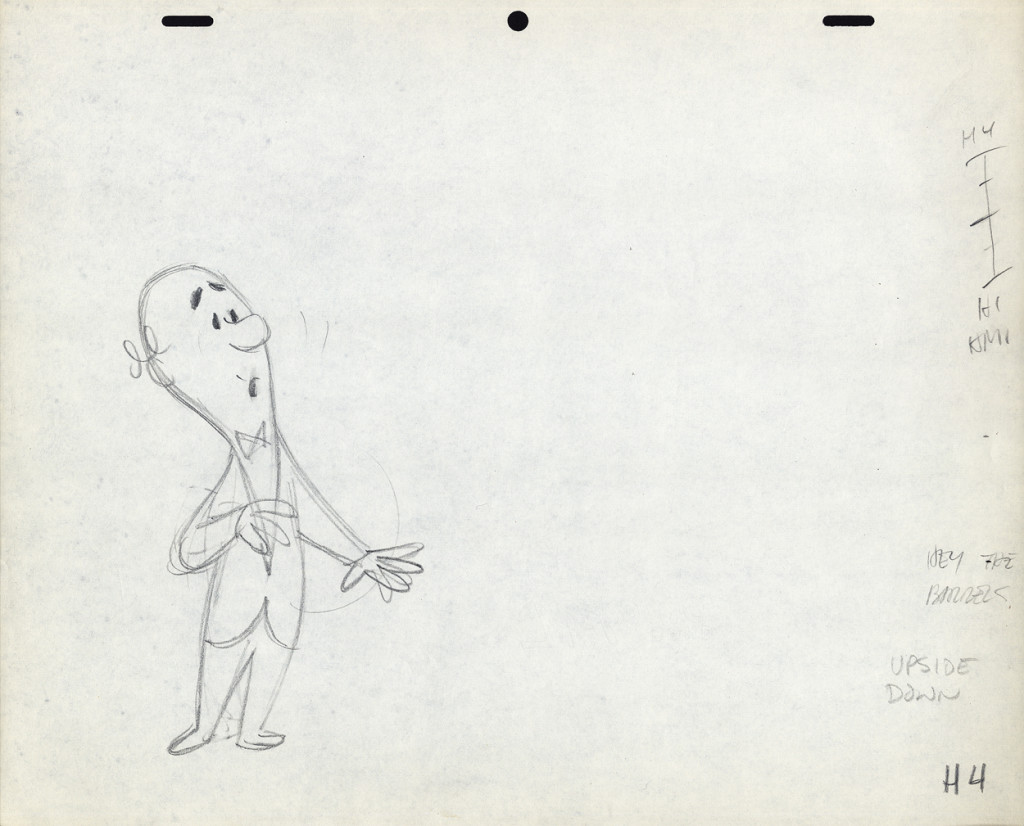

H9

H9

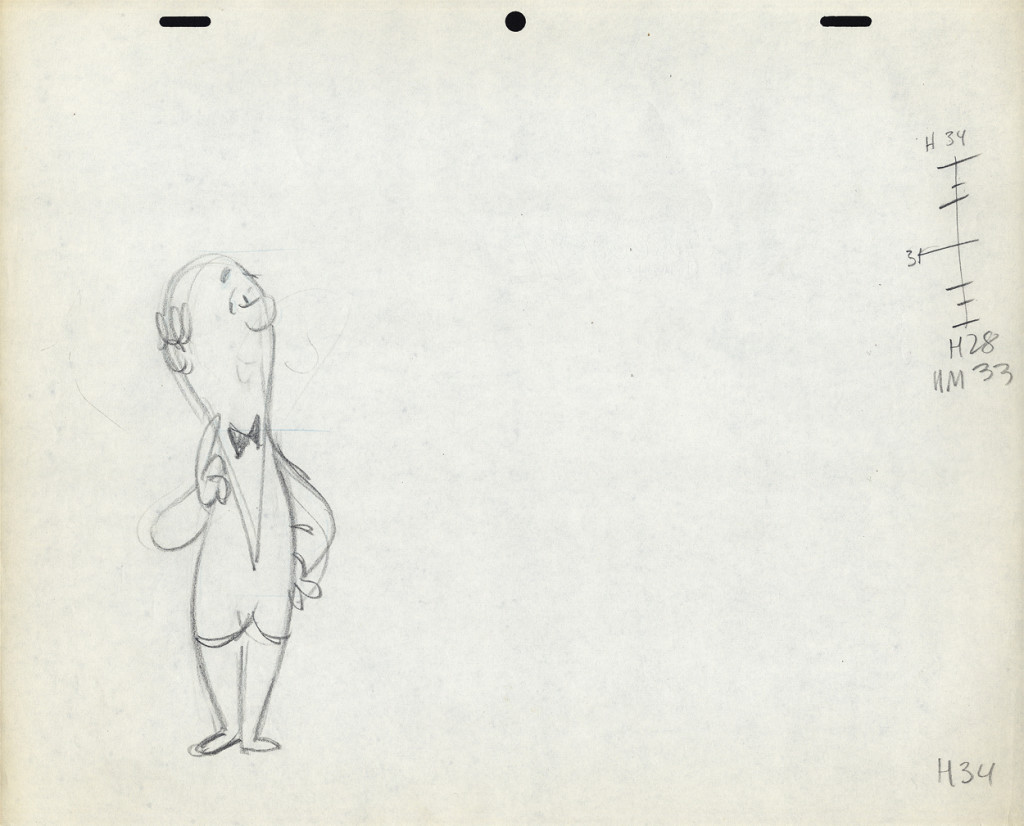

Again, the ladder appears on the later extreme. The assistant

shouldn’t have to go looking for it. The ladder should be on

the first drawing involved in the breakdown.

Again, the breakdown drawings are on 1/3′s, and

the inbetweens are 1/2′s of that. It makes it harder on the

people following up on the clean-up & inbetweens.

I don’t know if this style of Lu’s was a product of where he learned to animate or not. Jack Schnerk, a comparable animator – whose work I loved (even though he had a rougher, harder to clean up drawing style) – always broke his timing in halves and halves again. There were times when his animation went to one’s and he did most of all the drawings. I assumed he had an unusual timing, and he didn’t want to burden the Assistant with his schema. He also always carried the breakdown charts on the earlier numbered drawing – per Grim Natwick’s comment. In some way I felt that Lu was rushed to get on with the scene, and whatever method he used would be to get him there more quickly. (It was the assisting that was slowed down.) This may have been a product of his attempts to devise some type of improvisation in the animation. Lu’s work, on screen, was usually excellent, so he didn’t much hurt anything in his method.

It might also have been his method of trying to put SNAP into the animation. This was a WB trait from the mid-late Thirties. It was certainly in Lu’s animation. No doubt a hold-over from Clampett’s early days of directing.

The final thing to note is that Lu usually worked on Top Pegs. Animating on Top Pegs makes it impossible to “roll” the drawings and check on the movement of more than 3 drawings. You can only “flip” the three, checking the one inbetween, but it didn’t give you a good indication of the flow of the animation. This is obviously necessary in animating on paper. It also made it difficult for the cameraman as well as those following behind the animator. If there were a held overlay, this would have to be on bottom pegs since the animation is on top pegs. That requires extra movement of the expensive cameraman to change all the animation cels after lifting the bottom pegged overlay. It also risks the possible jiggling of the overlay as it’s continually moved for the animating cels.

on 04 May 2013 at 1:22 am 1.RodneyBaker said …

Fascinating. Studying the differences between the standardized method and improvised methods is as confusing as it is educational.

It makes me wonder if animating ‘backwards’ wasn’t a means to intentionally make the process more mechanical in order to ensure very mechanical/precise inbetweening…

on 04 May 2013 at 8:13 am 2.Michael said …

I think you misunderstood the note. No one anmated backwards. They just put the charts on the wrong drawings, making it difficult for the Assistant animator. Though perhaps animating backwards might be helpful to some people I’ve met.

on 06 May 2013 at 6:14 am 3.Peter Hale said …

The method of charting inbetweens had was not beenstandardised during the “Golden Age” at Disney’s – it seems to have been very much a matter of individual preference. Looking at random extremes it would seem that John Lounsbery (eg. from “Lady and the Tramp”) and Ward Kimball (eg. from “Alice in Wonderland”) put their charts on the ‘start’ extreme, while Milt Kahl (eg.s from “Pinocchio”, “Alice”, “101 Dalmations” and “Pobin Hood”) charted on the last extreme. All usually numbered down the chart, though, unlike Lu, who seems to prefer numbering up.

In the 70s I worked in a small commercials-based animation studio in London, where I assisted Bill Hopper, an animator who had been trained at Rank’s G-B Animation studio at Cookham, in the late 40s. Presumably they were trained in what David Hand considered was then ‘best practice’ at Disney. He always charted on the last extreme, and frequently used thirds.

I think this was just because it was the top drawing, and easiest to write on – it worked because firstly, in the early 30s animators were still doing most inbetweens themselves, and secondly, when they did get assistants they were animators-in-training and worked in the same room as the animator.

The need to ‘pander’ to the inbetweener, in order to facilitate production, comes, it seems to me, from working in other studios where inbetweeners did not work closely with the animator, and were not properly trained. Then, things had to be simplified.

It really in no harder (perhaps I should say ‘just as hard’!) to draw an inbetween at a third of the way through an action as opposed to halfway – animation is not mechanical, and inbetweens ought to reflect the differing speeds of movement of all the parts (as seen when flipping with the extremes preceding and following on from the ones actually being inbetweened) rather than be ‘perfect’ halfways. (The G-B animators were trained the hard way – they had to inbetween by flicking, without the aid of the lightbox!)

But I did come to appreciate the need to ease the burden on the inbetweener when giving work to freelancers, and I agree that thirds are best avoided, and spending a moment to decide on the right choice of which way to half-and-quarter (should it slow-in or slow out?) gives more life to a move.

on 06 May 2013 at 6:52 am 4.Michael said …

Unfortunately, if you animate as Lu did, going from one extreme to another – unexpected – extreme, the inbetweener then finds himself wasting time trying to find out where the chart is. For example, if I animate from 1 to 5 to 9, it would be expected that the next drawing would be 13. However, if I go from 9 to 13 then have a separate section where I reuse 5-9 then hook up to 33, it will be a waste of time (and production cost) for the inbetweener to then have to readdress the scene when he eventually finds a chart linking 9 to 33 (presumably 3,31,and 32 would be involved). Breaking the flow would be easier if it were done by placing the two sets of charts on drawing #9 thus alerting the inbetweener to the reuse.

Of course, a good inbetweener would usually work with exposure sheets and might have already analyzed Lu’s construction. (This was a matter of course for me when I inbetweened. (Note also that some studios don’t allow inbetweeners to work with the X-sheets.)