Action Analysis &Animation &Commentary &Frame Grabs &Tytla 25 Mar 2013 06:05 am

Smears, Distortions, Abstractions & Emotions – 2

- I wrote about this stylistic animation device not too long ago. I was leading up to the master, of course, Bill Tytla. He distorted things, alright, and in the way he did it, he changed animation forever, as far as I’m concerned.

But I started that story by writing about traditional animation and where it came from and where it was going; leading to a sort of rebellion as animators started distorting things, generally, in working closely with their unconventional directors. I purposely skipped a step there, and I should go back a tiny bit and talk about a couple of animators from the silent/early sound days. Today I have Bill Nolan in my sights; tomorrow, Grim Natwick. It’s kind of important before going on to Bill Tytla.

In the animation community in 1927-1930, there were two key animators who were considered the leaders in the business:

In the animation community in 1927-1930, there were two key animators who were considered the leaders in the business:

Ub Iwerks at Disney (until he left to open his own studio) and

Bill Nolan (at first with Pat Sullivan & Felix the Cat, then with Mintz’ Krazy Kat, and then onto a series of topical gag films called “Newslaffs.”

Both were considered the fastest animators in the country, and it was debatable as to which was quicker, though Iwerks was probably the guy. When Disney learned that Iwerks was leaving, he interviewed Nolan in New York to see if he were interested in replacing Iwerks. Disney offered a high salary of $150 per week for the job. It didn’t work out; Nolan was doing an unusual series, but ultimately went to ________________Nolan’s Krazy Kat looked original.

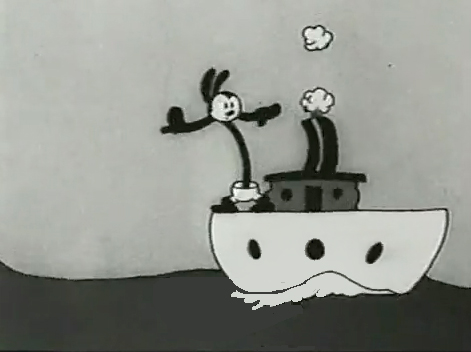

Oswald the Rabbit after Universal had taken

charge of it. Nolan just about ran the studio under Walter Lantz and allowed them to turn out an enormous amount of footage.

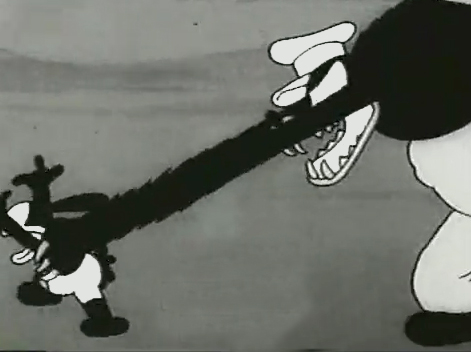

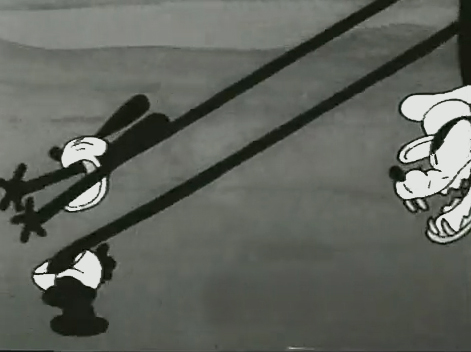

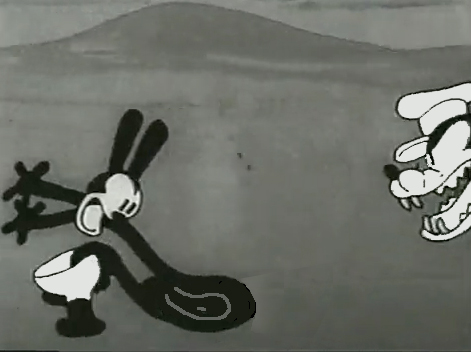

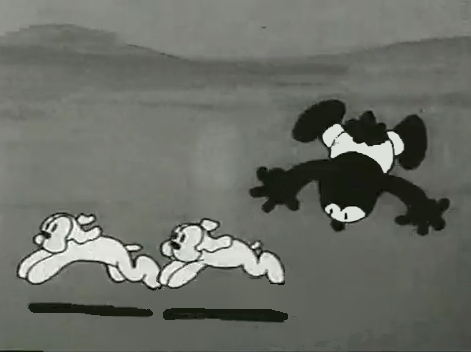

Nolan had developed a style known as the “rubber hose” style in that the limbs of a character were like flexible hoses and joints would be broken wherever the animator wanted. The style also featured very circular drawings. Stylistically, this fought the angularity of some other films that were being made and allowed Nolan to turn out many more drawings than usual. The roundness offered a faster line, and there was also quite a bit of distortion in Nolan’s drawings. Quite often the characters, Oswald, for example, didn’t even look like the character on the model sheet. In fact, you’d have to wonder if there was a model sheet, given the look of the animated character. Both Nolan and Iwerks were straight ahead animators, which meant they could easily go off model. Iwerks was better at holding things than Nolan, who seemed to enjoy being wild. Nolan would go back through his wild drawings and correct a couple of them, but would leave any other changes to lesser artists.

Nolan’s work was somewhat similar to the work of Jim Tyer, but I don’t think Tyer was drawing/animating that way to turn out faster work (though he was a very fast animator.) Nolan had to push the work out, and the rounded, distorted drawings enabled him to animate very quickly. As he went on, the artwork grew more and more wild, and it varied somewhat from the other animators’ work. Tyer tried to get his art to distort, as it does; Nolan just ended up there.

1

1  2

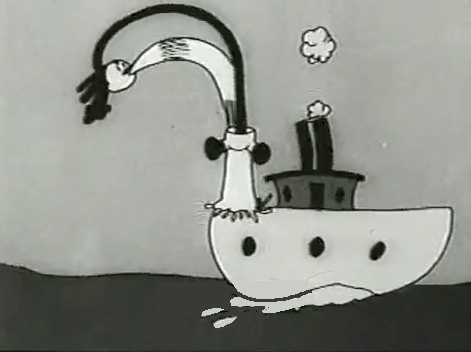

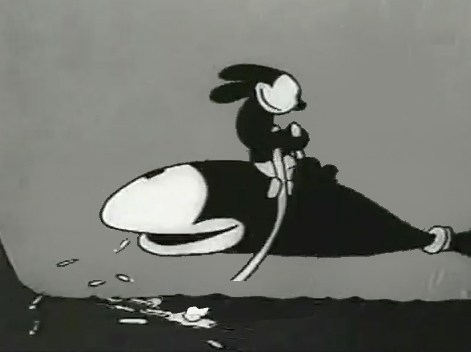

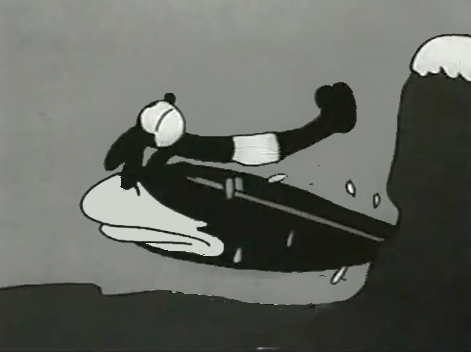

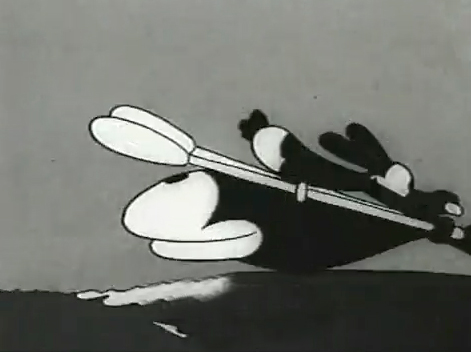

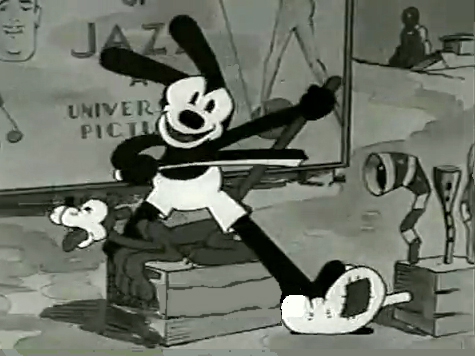

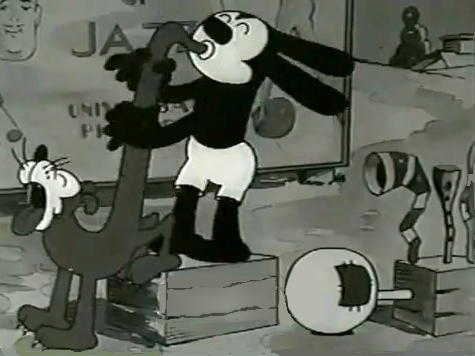

2I’d chosen a lot of stills from several of the

Universal/Lantz Oswald cartoons, animated by Nolan.

3

3  4

4

But so many of these from the short, “Permanent Wave,”

are good enough to illustrate my point.

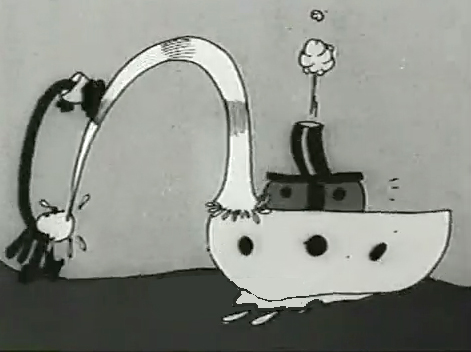

13

13  14

14

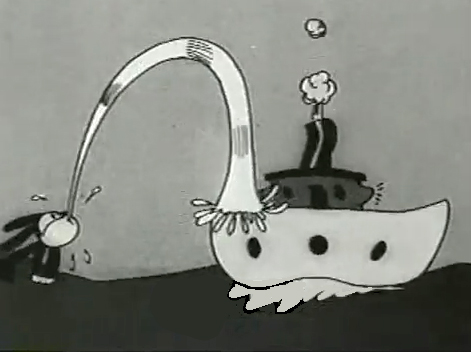

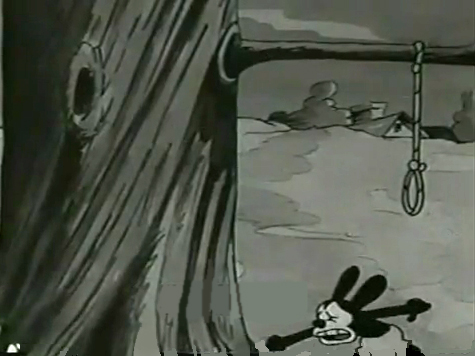

His body moves out in front of his head

as it climbs up the water he’s spitting onto the boat.

“The Hash Shop” was about as crazy as the animation and the gags went. Here’s one that ends the film.

By 1930, Bill Nolan seems to have settled down a bit. He still abstracts and distorts his animation, but he tries to fit in a bit more with other animators who aren’t drawing their animation quite so abstractly.

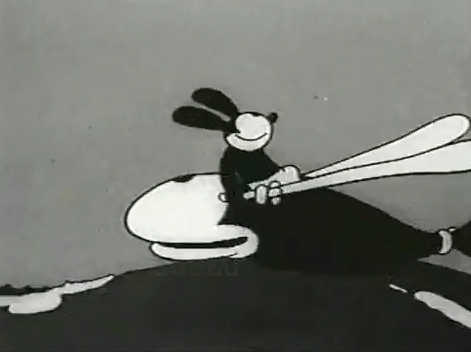

After Disney’s “The Three Little Pigs,” other studios tried to catch up with this new type of animation. Nolan and, to a lesser extent, Lantz, didn’t try very hard to change. They liked the way things were going. However, it didn’t take long for Lantz to move for a change in Oswald’s design. They went cuter and whiter on the rabbit.

Here are some frame grabs from “My Pal, Paul.” In it Oswald wants to play music with jazz conductor/musician, Paul Whiteman. As it happens, Whiteman’s car breaks down while he’s driving through the woods, and the two get a bit of a duo as Whiteman plays the steering wheel like a clarinet. (Maybe that’s abstract enough.)

on 25 Mar 2013 at 6:20 pm 1.Kevin Hogan said …

“Tyer tried to get his art to distort, as it does; Nolan just ended up there.” Perfectly sums it up.

I don’t think of Nolan’s animation as wild, per se- I see his work as loose, lacking in character acting (as most animation was at that point) and unpretentious. I would agree that he was not one to worry about model sheets, as it seems that the model was simply a starting place.

on 25 Mar 2013 at 10:36 pm 2.Nat said …

These Oswald cartoons certainly weren’t as fluid or as well thought out as the earlier Disney ones, but you nailed it. Man, they were fun with all their wacky and surreal drawings.

on 26 Mar 2013 at 7:03 pm 3.Stephen Worth said …

Bill Nolan’s Oswalds, especially the early ones are a million times more inventive and alive than the Disney ones. Nolan was a drop dead genius.

Some people seem to think that this sort of animation is “primitive” and loose animation drawings are a sign of poor draftsmanship. Nothing could be further from the truth. All it takes to imitate realistic movement is lots of pencil mileage and reworking and refining. This sort of movement comes from direct inspiration and finding the way to draw movement, not still images. Grim had a bunch of different ways to draw, all for different purposes. He told me that he could make the turns from style to style so easily because of his training in Vienna.

“Acting” in the context of this type of animation is often misunderstood too. I don’t know a better example of acting in animation than Betty Boop singing in Mysterious Mose. It’s better than a lot of the more “sophisticated” acting that came later. In fact, I would be hard pressed to think of another female character in the history of animation that comes close.

on 27 Mar 2013 at 2:02 pm 4.Kevin Hogan said …

I agree with you, Stephen, that there is a distinction between “primitive” and “loose” animation. Nolan is one of the linchpins in that middle period between the silent era and the so-called Golden Age that started in the 30′s.

When I refer to “acting”, I mean the character conveying emotions/ thinking through subtle movements. There are, of course, other ways to convey such things- the distortion of the body to convey the inner-thoughts of a character that Michael is talking about is another way. Much of “acting” in the early sound era is conveyed through distortion and energy- and I think this kind of acting evolved and grew as the 40′s moved along, resulting in Clampett and others.

I hope that clarifies my meaning.

on 28 Mar 2013 at 7:38 pm 5.Stephen Worth said …

The animation of Betty’s face as she sings Mysterious Mose follows the inflections of the voice recording as closely as the most subtle Disney acting ever done. But it goes one step further, reflecting her attitude through abstract, yet contextual movement. Later animation was better assisted and had tons of overlapping action and polish, but Grim’s best animation of Betty still stands out as being remarkably well acted.

on 28 Mar 2013 at 7:39 pm 6.Stephen Worth said …

By the way, Grim learned a lot from Bill Nolan when he worked with him at the Krazy Kat Studios.