Articles on Animation &Books &Commentary 18 Feb 2013 04:59 am

Appreciation

The deeper you go, the deeper you go.

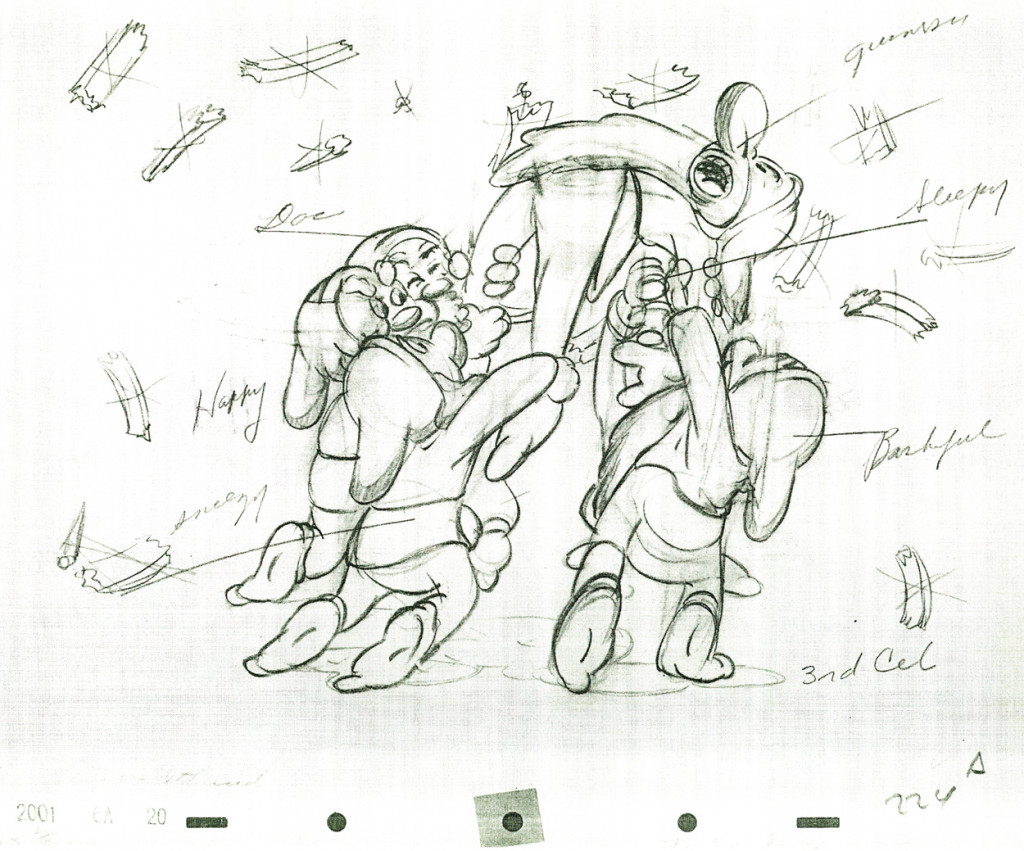

In reviewing the two J.B. Kaufman books on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I found them impeccable in their attempt to reconstruct the making of this incredibly important movie. They followed a strict pattern of analyzing the film in a linear fashion going from scene one to the end.

In reviewing the two J.B. Kaufman books on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I found them impeccable in their attempt to reconstruct the making of this incredibly important movie. They followed a strict pattern of analyzing the film in a linear fashion going from scene one to the end.

However, the analysis Kaufman offered brought me back to the bible, Mike Barrier‘s Hollywood Cartoons. Rereading his chapter on Snow White, you realize how much depth he offers in a far shorter amount of space. Of course, there are few illustrations in Barrier’s book, but what writing is there is golden. He meticulously analyzes the work of different animators using a very strict code of principles. If you can agree with him, the book he’s written opens up enormously.

However, the analysis Kaufman offered brought me back to the bible, Mike Barrier‘s Hollywood Cartoons. Rereading his chapter on Snow White, you realize how much depth he offers in a far shorter amount of space. Of course, there are few illustrations in Barrier’s book, but what writing is there is golden. He meticulously analyzes the work of different animators using a very strict code of principles. If you can agree with him, the book he’s written opens up enormously.

Once you get to the chapter, post-Snow White, which catalogues the making of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo you are in the deep water. Mike pointedly criticizes some of the greatest animation ever done. His analysis of Bill Tytla’s Stromboli is ruthless. Though I am an enormous fan of this animation, I cannot say I disagree with what he has to say. Though I think differently of the animation.

Once you get to the chapter, post-Snow White, which catalogues the making of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo you are in the deep water. Mike pointedly criticizes some of the greatest animation ever done. His analysis of Bill Tytla’s Stromboli is ruthless. Though I am an enormous fan of this animation, I cannot say I disagree with what he has to say. Though I think differently of the animation.

Here’s a long excerpt from this chapter:

- No animator suffered more in this changing environment than Tytla. His expertise is everywhere evident in his animation of Stromboli—in the sense of Stromboli’s weight and in his highly mobile face—but however plausible Stromboli is as a flesh-and-blood creature, there is in him no cartoon acting on the order of what Tytla contributed to the dwarfs. At Pinocchio’s Hollywood premiere, Frank Thomas said, W. C. Fields sat behind him, “and when Stromboli came on he muttered to whoever was with him, ‘he moves too much, moves too much.’” Fields was right-although not for the reason Thomas advanced, that Stromboli “was too big and too powerful.”

- In the bare writing of his scenes, Stromboli, more than any of the film’s other villains, deals with Pinocchio as if he were, indeed, a wooden puppet—suited to perform in a puppet show, and perhaps to feed a fire—rather than a little boy. But the chilling coldness implicit in the writing for Stromboli finds no echo in the Dutch actor Charles Judels’s voice for the character. Judels’: Stromboli speaks patronizingly to Pinocchio, as he would to a gullible child, and his threat to use Pinocchio as firewood sounds like a bully’s bluster. As Tytla strained to bring this poorly conceived character to life, he lost the balance between feeling and expression. The Stromboli who emerges in Tytla’s animation is too vehement, “moves too much”; his passion has no roots, and so he is not convincing as a menace to Pinocchio, except in the crudest physical sense. There is nothing in Stromboli of what could have made him truly terrifying: a calm dismissal of Pinocchio as, after all, no more than an object.

- To some extent, Tytla may have been overcompensating for live action that even Ham Luske acknowledged was “underacted.” But Luske defended the use of live action for Stromboli by arguing that it had kept Tytla on a leash: “If he had been sitting at his board animating, without any live action to study, he might have done too many things.”

I agree, as Barrier says, that Stromboli is a flawed character, and I agree that the movement is broad and overstated. However, I think that this was Tytlas’s only possible entrance into the material, into trying to further the characterization. No, it could not be as deep as the work he’d done on Grumpy in Snow White, but the character of Stromboli isn’t as small as that name, “Grumpy”. A lot more was offered and had to be circled to simplify as best as possible for the small amount of screen time he would have in Pinocchio. And, yes, he comes off like a blowhard with a lot of bluster. But that’s not the way Pinocchio sees him. Pinocchio is made of wood, as Stromboli reminds us, but he is also an innocent, a child learning about the world.

Barrier’s chapter, as I said, moves quickly through this material covering four of the greatest Disney films; no, four of the greatest animated features ever done. In relatively few pages you feel as though he’s gotten it all in there and has even said more in depth than almost any historian about this period of Disney animation. I’ve read this chapter at least a dozen times, and it continues to grow richer for me. I think it’s possible the greatest piece ever written about animation.

Barrier’s writing, vocabulary, choice of phrase is all charged to keep the material tight. He’s writing a large book, and he has to get a lot in.

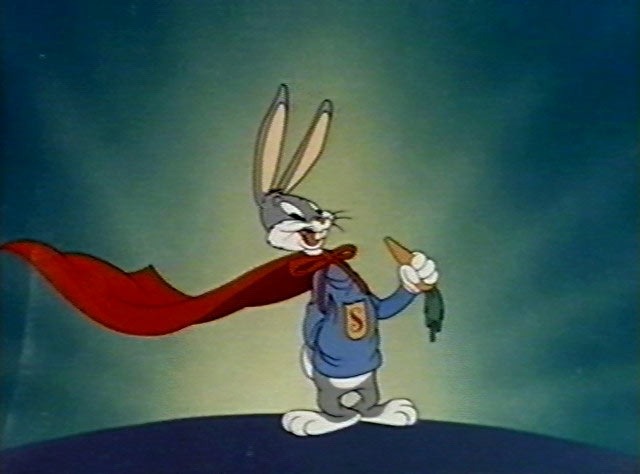

Perhaps some day he will have one of those big picture books to write where he will have the freedom to expound on the material. I did once read such a book. Mike Barrier had been employed to write a history of the Warner Bros. studio, and I got to read the first draft of the manuscript. I had a couple of hours and sat in a chair, thumbing pages. The images that were to be in the book were on large chromes. It was all an extraordinary experience for me, and I remember it somewhat hazily, as if remembering a golden afternoon. Of course that book was cancelled when management changed hands, and the world lost a great book.

Perhaps some day he will have one of those big picture books to write where he will have the freedom to expound on the material. I did once read such a book. Mike Barrier had been employed to write a history of the Warner Bros. studio, and I got to read the first draft of the manuscript. I had a couple of hours and sat in a chair, thumbing pages. The images that were to be in the book were on large chromes. It was all an extraordinary experience for me, and I remember it somewhat hazily, as if remembering a golden afternoon. Of course that book was cancelled when management changed hands, and the world lost a great book.

Can there be any wonder that I go to the Barrier website daily, knowing full well that it’s often months between posts? I just keep looking for new material from him, and will continue my daily routine hoping for the small brightly colored package on his site. It’s almost important for there not to be frequent posts or the new ones wouldn’t always shine as well. However, two or three times a year, there is something rich there, and my search has brought the golden fish. (Yes, I’m exaggerating somewhat like Tytla did in his animation of Stromboli. But the point gets made.)

Even if there’s nothing new there, there’s plenty old. Many old Funnyworld articles or interviews done with Milt Gray. It’s a deep site full of deep writing.

on 18 Feb 2013 at 7:08 am 1.peter hale said …

I’m also a big fan of Mr Barrier and, since CartoonBrew dropped their links column, I use his site as my base for visiting the other animation blogs I follow.

I don’t have much of a problem with Stromboli, and rather think that his personality and behaviour would have been pretty much determined during the later story meetings.

‘Pinocchio’ has 3 levels of villains (4 if you count Monstro) and I think the Studio would have made quite an effort to define their differences.

The lowest level is the knock-about clowning of ‘Honest’ John and Gideon, who are ‘petty criminals’ – itinerent opportunistic thieves and conmen.

The highest is the Coachman – he uses understatment to underline the threat of his criminal power – he is ‘organised crime’.

Stromboli falls in the middle, and he is depicted as the ‘exploitative employer’ – he is a showman, so is all bluster and performance. He knows he cannot really harm Pinocchio, because the living puppet is his mealticket, but he must threaten and dominate him in order to bind him in obedience.

I think Tytla makes a good job of the blustering bully persona.

(I am not, of course, suggesting that Disney was trying to make the villains representative of the group-types I’ve used – there is no intention of political allegory! – merely that they built on the different aspects of the villains, and their stereotypes fall into those categories.)

on 18 Feb 2013 at 8:53 am 2.Thad said …

Rank heresy it may be to say so, but maybe Tytla probably would have petered out the way he did anyway even if he did stay at Disney’s and never went on strike. There was less and less opportunity for the kind of animator Tytla was in those later films.

But – even in his lesser assignments at Disney’s, he could instill a life that he just couldn’t at Terry, Famous, or his commercial studio. I wrote this to Mike Barrier a while back, just because the thought came to me, but had no place to put it. I might as well post it here:

I’ve come to the conclusion that he did not have much use for caricature. Rather, he was far more observational in his nuances – that is, instilling his characters with soul without using distortion for purely exaggeration’s sake because he’s such a keen observer of what made people tick that he doesn’t need to. Even in as vacuous a film as SALUDOS AMIGOS, compare Tytla’s animation of José Carioca to Fred Moore’s. Both are great, but in Tytla’s introduction of the character, there is a profound sense that José is one of those overly-friendly Latinos unaware that he’s invading the white guy’s (Donald’s) personal bubble that Tytla probably saw in New York on a regular basis. Not as overt as the dancing/drinking of Moore, just very subtle and natural. I don’t sense anything in the same league from any other artist on that film, even the ones who went on the trip.

on 18 Feb 2013 at 9:35 am 3.Michael said …

To some extent I agree with you, Thad. However, it’s doubtful that he would have totally vanished under the veneer of the live action reference material others fought on Cinderella, Peter Pan et al. Maybe Ferguson and Fred Moore would have lived on as strongly if they hadn’t turned to alcohol to help them animate. Their’s was an insecurity problem.

Tytla tried to be the same animator later in his career. The finances behind his projects just didn’t support it. When he was directing/animating, for a short while, o FINIAN’S RAINBOW he tried to keep things at the top of the game. A friend, and Asst Animator, whose desk was just outside Tytla’s office listened to him consulting with an animator he was directing. He made the guy roll up his pants so he could see his legs in a wall-length mirror Tytla had on his office wall. Ttla made the guy go through the dance steps many times while they watched themselves in the mirror. He was trying to get the purpose of the animation across, yet those outside the office gigged at the way Tytla was “embarrassing” the under animator. This is not something most people did in commercial studios. But he could no longer afford what he was doing on the Disney features.

Perhaps he would have been able to turn the other Disney animators in his direction. Lord knows reports make it seem as if several of them wanted (and did) follow that method – ignoring the roto drawings. Milt Kahl received the drawings, and threw most of them in the trash.

The unfortunate thing is that we can’t predict the future of the past any more than we are doing here. If Jim Tyer had developed his style at about the time he died, would his style have been killed by the many commercials he would have had to animate. Could he have operated well outside of the theatrical films he was doing for the third tier animation studios? What about Rod Scribner? Could he have done what he did without Bob Clampett? Bob McKimson killed him artistically. Wouldn’t he have had the same in any other studio?

The fortunate thing is that we have these shooting stars to mimic when we do animation. Unfortunately, thanks to the teaching of Dick Williams and Art Babbitt today’s 2D animators are, for the most part, stuck in a realistic mode and rarely even go to a “hold” when they animate. Everything has to be on “ones” and animation is, for the most part, muddy. We need another shooting star.

on 18 Feb 2013 at 11:12 am 4.Thad said …

You’re right that we can’t predict the future of the past, and it kind of is a waste of time. It’s a descension into fantasy baseball/football territory. But it can still be fun, as most time-wasters are.

The most tragic part about Bill Tytla is that he never lost the ability the way Moore, Fergy, and Scribner did (at least not until the 60s). He always had the ability – he just never had the opportunity.

on 18 Feb 2013 at 2:01 pm 5.J Lee said …

There was a certain mindset during the classic Disney era that Italians were passionate and ‘moved a lot’, which carried over to pop culture in general (even on the radio, if you hear Alan Reed in “Life with Luigi”, you know you’re supposed to be visualizing a character moving a whole bunch).

The restaurant scene in “Lady and the Tramp” was a later example of that, albeit in a non-threatening manner compared to what Tytla was doing with Stromboli. Judels’ voice notwithstanding, Stromboli was the most obvious ethnic character in “Pinocchio” and the idea of giving him added movements fit the template of the time of what that sort of ethnic character should be doing.

on 18 Feb 2013 at 4:40 pm 6.Charles Kenny said …

Hollywood Cartoons is an excellent book. I thought it would sustain me through 10 days in St. Lucia but barely made it half that!

It also really did give me a better understanding of the various studios’ shorts through the 30s too. An area I realised I had subconsciously avoided until then.

on 18 Feb 2013 at 5:15 pm 7.Michael said …

Comparing Luigi to Stromboli is an interesting choice. Yoiu’re right that there is a difference, though I think even Stromboli’s tyle of acting would have worked for Luigi. Excellent food for thought.

on 19 Feb 2013 at 12:52 am 8.Stephen Worth said …

I love Stromboli’s animation, not because of the plot based things that an “animation historian” or “film critic” sees, but because of the things only someone in animation sees. Stromboli’s animation is full of clever cheats that he must have learned at Terry Toons. His eyes drag around his face and his mouth leaps off in strange directions- but it all works perfectly. Disney animation can be way too studied and constructed. But Tytla went beyond that, creating a hyper structured performance that defies logic and satisfies logic at the same time. That’s what animation should do.

on 19 Feb 2013 at 1:01 am 9.Stephen Worth said …

Tytla’s animation of Mighty Mouse getting drunk in The Mouse and the Lion is brilliant in the exact same way. There’s a loopy charm to the movement that Disney rarely achieved (except with some of Ward Kimball’s scenes). I like animation when it’s more spontaneous and less studied. Tytla wasn’t afraid of doing this. Many animators are. They doubt themselves and work on details far beyond their inspiration. Irv Spence is great at this sort of directness too.

on 19 Feb 2013 at 10:21 am 10.Bill Benzon said …

Reading this sent me back to Hollywood Cartoons, Michael, and naturally enough I found something in Ch 6 that speaks to my fascination with Fantasia. The most salient bit is simply that Disney was more engaged with it than with Pinocchio. Given that he was temperamentally an explorer that makes sense. Pinocchio may haven been variously different from Snow White, but it was still a narrative film. With Snow White he’d shown that the animation medium could sustain a feature-length narrative. Pinocchio could at most strengthen the demonstration, but it couldn’t do anything THAT dramatically new.

In contrast, Fantasia WAS something new. And Barrier has a few quotes from Disney that indicate he really was trying to do something new and different, something for which no model existed.

Good stuff. It’s a fine book.

on 19 Feb 2013 at 3:39 pm 11.Liim Lsan said …

I once compared Stromboli, for a would-be Barrier acolyte who felt the need to criticize everything, to a deliciously cooked and spiced tenderloin that’s been drowned in A-1. As a southerner, she got the metaphor immediately.

Stromboli, when seen in motion, looks like a quivering ball of lines and stock Disney overlapping actions.

But when you watch it frame by frame, you almost have a heart attack at the sheer wunderkunstwerk. His secondary action is flawless, his emotional state is revealed in every twitch, and you can see hundreds of mental layers operating as he gets angry, fights his anger, tries to retain composure, and fights with his own mouth to pronounce the English dialogue that comes so uneasily to him. Tytla STARTS with that and plays endless variations on it as he becomes alternately patronizing, hopeful, sarcastic, malicious, fruity, and above all sublimely arrogant. His hands change graphic shape numerous times, and always to highlight what Bill Tytla wants us to focus on. His hips are like a Wagner brass section, highlighting his every emotional shift. It’s a tour de force.

Problem is, it isn’t done successively, like Grumpy (where he has to look up before he starts crying, or change his step as he walks), who does things in clear order for the audience. Stromboli, it all happens at once, his mental states are layered on top of each other. I wouldn’t expect anyone to be impressed with the full power of the animation when they watch it without quite looking, or don’t absorb the subtleties Bill rubbed into the meat. I’m convinced that’s what Barrier was complaining about; between the disconnect between the voice and character and the sheer impenetrability of the performance’s complexity.

And SWEET JESUS Barrier was writing a Warners book? I have no words to say to this. I’ve taught a high school class on action analysis with their shorts, and even I know that there’s nobody who could say it better than Barrier. (On Tashlin and McKimson and mature Freleng, he’s incredibly distant in “Hollywood Cartoons.”)

on 19 Feb 2013 at 5:42 pm 12.Michael said …

Boy, do we disagree on Michael Barrier’s work. I don’t necessarily agree with him on everything he says (nor does he agree with em) but I’m always informed by everything he says. He is the most astute and intelligent of animation historians and critics, and I wish there were just two or three more like him. (Others are getting close, but no cigar yet.) As I start the article, “The deeper you go, the deeper you go.” I can’t think of many other ANIMATION writers I can say that about.

on 20 Feb 2013 at 4:37 pm 13.Kevin Hogan said …

I have always felt that the best asset (and, as is usually the case, the greatest weakness) of Pinocchio is its excess. I loved the vidid details in the backgrounds, the one-or-two-or-three too many villians, and its plot exaggerations (clearly Pinocchio is only gone a day or so at Pleasure Island, but the Gephetto house is filled with cobwebs- Hollywood Cartoons is quick to point that flaw out).

I saw the excessive movement of Stromboli as being in perfect tone with the movie. The fox and cat were bumbling, the coachman was silently devious, the whale was furious, and Stomboli was a showman. Everyone around Pinocchio was larger than life, creating a sense of chaos in the film.

I love Michael Barrier’s writing, and I also visit his site with comments often. While I agree with his overall point of Stromboli’s excess, I must say the excess is (I think) the film’s point. The world is scary and it doesn’t make sense- as Pinocchio finds out.

on 21 Feb 2013 at 8:10 am 14.peter hale said …

I’ve never had a real problem with the time-scale of Pinocchio. The cobwebs in Geppetto’s house are there deliberately, to tell us that a lot of time has elapsed between Pinocchio’s and Jimminy’s dive off Pleasure Island and their arrival back in the village.

Pinocchio was picked up by coach at the crossroads at midnight (according to the Coachman’s plan). The coach ride sequence we see seems to be taking place at dawn. The steamer to Pleasure Island seems to sail in the evening. Hence, at least a day’s travel is indicated, by land (at speed) and by sea.

For Pinocchio to swim back to shore must take some time, and then he has to figure out where he is and how to get back home. On foot.

A conservative estimate would be that this could take a week or more. In fact, as the return home reveals, months have elapsed.

Since the film is specifically saying “much time has passed”, why should we disbelieve it?

on 22 Feb 2013 at 8:27 am 15.Kellie said …

On the cobwebs: One way of looking at the film is as a story of the artist (played by Geppetto) whose creative drive is pitted against his fear of death. His work is an attempt to combat death by creating new life, but the results of his creativity are mechanical clockwork imitations of life. As Geppetto sleeps, Pinocchio’s coming to life expresses Geppetto’s desire to go beyond imitation, but the anxiety that his creation isn’t really alive persists.

The scene of a deformed Pinocchio returning to the cobweb-covered workshop can be seen as Geppetto being overcome with fear of his work being seen as a grotesque joke after his own departure (death). Consequently he sinks into a deep depression in the belly of Monstro.

In the climax Geppetto escapes depression by transferring his fear of death onto Pinocchio, and resolves it by believing in the life-power of his work (“real boy”).

The story seems like Geppetto’s dream, and I think trying to pin down what day it is in the story makes as much sense as trying to rationalise the chronology of a dream.

on 05 Mar 2013 at 4:07 pm 16.Kevin Hogan said …

Not that I care very much about the cobweb timeframe either way- I’m definitely in agreement with Mr. Barrier on this one. I think the cobwebs only confuse the audience and have us wonder about the timeline needlessly. The film did not need to raise questions about how long Pinocchio was away (we would feel simpathy for Geppetto either way), and the film is weaker with the cobweb’s inclusion.

But, as I stated in my earlier comment, visual and story hyperbole make the film what it is- a great metaphor for life’s cruelties. I can’t blame the Disney staff for trying to emotionally manipulate us a bit with the cobwebs.

on 28 Jul 2013 at 1:36 pm 17.john wunder business said …

Heya now i am with the primary time below. I discovered that plank i in discovering This process valuable & this reduced the problem out and about a good deal. I really hope to supply one thing yet again as well as assistance some others such as you helped me.