Animation &Commentary 15 Mar 2011 07:35 am

The Insanity Defense

- Mike Barrier recently posted two interviews on his website: Robert McKimson and John Hubley. On Saturday, I added a few small comments about the interviews. This caused a couple of comments from readers who got into the McKimson interview with some strong statements about McKimson’s treatment of animator, Rod Scribner. Scribner had taken a 3 year break from animating to treat his Tuberculosis. When he came back to the studio, he no longer was able to work in Clampett’s unit – he’d left the studio -, so Scribner found himself, ultimately, in Robert McKimson’s group. Seen as a wild animator by McKimson, Scribner was molded into something much less violent. It seemed the juice was taken out of his animation.

The question was whether it was the TB, heroin, electric shock therapy, or just McKimson that caused this enormous change in Scribner’s style. If we go back to the interview, I think we can find the answer. In McKimson’s words:

I had one animator, who thought he was better than he was, and I’d just flip it through, and I’d say, well, this has got to be changed, it won’t work this way. He said, “I think it will.” I said, “All right, Rod [Scribner], you go and test this”—cheap negative testing—”and we’ll run it on the movieola, and I’ll show you what I mean exactly.” He said, “All right, but I know it’s right.” Every three to six months, he’d come up with one of these things. So I’d just tell him to go ahead and shoot it. We’d put it on the movieola and run it through and through, on the loop; every time, he’d say, “Yeah, yeah, I see what you mean.” And then the next time, he’d say, “Well, I think it’s right.” But that was the only way it worked against me. I had to take guys with a little less ability and try to make something out of them.

I had one animator, who thought he was better than he was, and I’d just flip it through, and I’d say, well, this has got to be changed, it won’t work this way. He said, “I think it will.” I said, “All right, Rod [Scribner], you go and test this”—cheap negative testing—”and we’ll run it on the movieola, and I’ll show you what I mean exactly.” He said, “All right, but I know it’s right.” Every three to six months, he’d come up with one of these things. So I’d just tell him to go ahead and shoot it. We’d put it on the movieola and run it through and through, on the loop; every time, he’d say, “Yeah, yeah, I see what you mean.” And then the next time, he’d say, “Well, I think it’s right.” But that was the only way it worked against me. I had to take guys with a little less ability and try to make something out of them.McKimson, the director, couldn’t work with the strong presence of Scribner – in fact he saw it as bad animation – and had to train Scribner into settling down to a less noticeable style of movement. Perhaps, Scribner was well ahead of his time and McKimson was behind the times?

The two animators I see closest in style to what Scribner did were Bill Tytla and Jim Tyer. All three worked in very different ways, and Scribner had more in common with Tytla and Tyer than Tytla and Tyer had with each other.

I believe there are two very different styles of animation: in one, all movement and thought is designed for the development and construction of the character; in the other, 2D animation is seen as a graphic challenge, and the shape and graphics of the character are above and beyond even the character, itself.

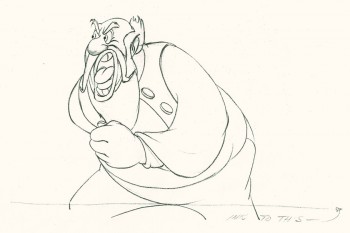

Bill Tytla worked at Disney for all his famous years. Within those walls the character was EVERYTHING. Tytla found that by distorting the character, in a very malleable way, he was able to accent traits of the characterization he was aiming for. Hence, a Stromboli would completely distort between two poses to accent a bit of violence. The character would come back together, on model, as soon as the strong gesture was made. Normal viewers, not looking for the distortion, didn’t see it but probably felt it. The strength of the movement was successful. I think Tytla saw this as a way of getting his animated character into the model Stanislavsky had suggested. This theory of acting was just starting to break through the Hollywood gates.

Bill Tytla worked at Disney for all his famous years. Within those walls the character was EVERYTHING. Tytla found that by distorting the character, in a very malleable way, he was able to accent traits of the characterization he was aiming for. Hence, a Stromboli would completely distort between two poses to accent a bit of violence. The character would come back together, on model, as soon as the strong gesture was made. Normal viewers, not looking for the distortion, didn’t see it but probably felt it. The strength of the movement was successful. I think Tytla saw this as a way of getting his animated character into the model Stanislavsky had suggested. This theory of acting was just starting to break through the Hollywood gates.

At least, this is my theory. John Hubley once told me that “… a small group of them at Disney were strongly into Stanislavsky. The rest,” he said, “couldn’t spell it.” I know that Hubley and Tytla were friends as was John Hench, and I’m sure they are who he meant. All you have to do is look at the Devil in NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN for obvious evidence of this.

Rod Scribner seemed to have an innate sense of this, but took it a bit further. I don’t think he thought of Stanislavsky, but he did think of graphics. In Barrier’s masterpiece of a book, Hollywood Cartoons, he tells a story about Scribner and Clampett. Apparently, Scribner approached Clampett and asked if he could introduce a “Lichty” style into his animation.

Rod Scribner seemed to have an innate sense of this, but took it a bit further. I don’t think he thought of Stanislavsky, but he did think of graphics. In Barrier’s masterpiece of a book, Hollywood Cartoons, he tells a story about Scribner and Clampett. Apparently, Scribner approached Clampett and asked if he could introduce a “Lichty” style into his animation.

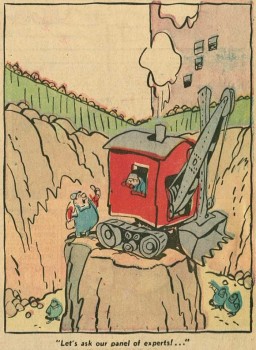

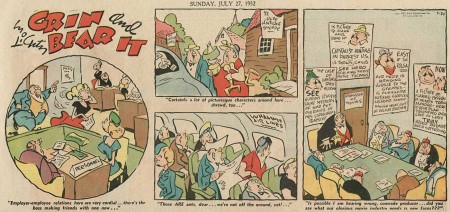

George Lichty was a well-known comic strip cartoonist (Grin and Bear It) who had a very loose, linear style. Scribner, obviously, was going for a two dimensional graphic style that he thought would work well in animation. Clampett understood what Scribner wanted and decided when to go along with it. It would take some careful editing to get it to work. Consequently, Clampett would reserve specific scenes and times to use the style which Scribner developed for those particular scenes the director gave him.

Lichty’s style

Consequently, Clampett was using Scribner, just ast Tytla designed for himself, getting the most out of the graphics without calling attention to the wild change in stylization. This first appeared in A Tale of Two Kittens then in Coal Black and de

Sebben Dwarfs. For me, The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is one of the highlights of this wild style as Daffy Duck transforms violently before our eyes – for frames only – before returning to himself. Even then, it isn’t quite the same Daffy that other animators drew. The two, Clampett and Scribner, used it outrageously in many of their films together; some work, some don’t.

Sebben Dwarfs. For me, The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is one of the highlights of this wild style as Daffy Duck transforms violently before our eyes – for frames only – before returning to himself. Even then, it isn’t quite the same Daffy that other animators drew. The two, Clampett and Scribner, used it outrageously in many of their films together; some work, some don’t.

Robert Mckimson was a mundane and lackluster director who, quite frankly, didn’t understand the stylization that Clampett and Scribner had developed. It’s no wonder McKimson broke it out of Scribner’s art when he became the director. To him it was just distortion, for its own sake.

Jim Tyer was a different animal. His distortion seems to be completely and wholly graphic. He doesn’t use it to develop a character; he uses it as the embodiment of the character. The character starts off-model and goes from there wildly and totally beyond the model sheet. It’s wholly graphic embellishment, and character be damned. This is something that Bill Tytla would have disliked, and many others within Terry’s studio as well. I remember Johnny Gentilella telling me that they couldn’t keep Tyer on model. Another assistant animator told me it was a hell of a job for her to bring Tyer’s character back, closer to the model sheet. I can imagine.

Jim Tyer was a different animal. His distortion seems to be completely and wholly graphic. He doesn’t use it to develop a character; he uses it as the embodiment of the character. The character starts off-model and goes from there wildly and totally beyond the model sheet. It’s wholly graphic embellishment, and character be damned. This is something that Bill Tytla would have disliked, and many others within Terry’s studio as well. I remember Johnny Gentilella telling me that they couldn’t keep Tyer on model. Another assistant animator told me it was a hell of a job for her to bring Tyer’s character back, closer to the model sheet. I can imagine.

All three of these animators have gained fame in the current state of the art. Young bloggers post frame-by-frame detailed distortions by Tyer, animators break down Scribner’s work with Clampett to see how exactly he did it. Tytla’s work is praised to the hilt drawing by drawing with delight taken in every distortion.

I have to say that I have always been a fan of Tytla’s and Tyer’s work. When I started doing animation professionally, I found people praising Tytla and putting down Tyer. I kept my love of Tyer secret. Over time, I grew to love Scribner. With all three I studied their animation frame by frame over and over. I was pleased that the folk who did The New Adventures of Mighty Mouse on CBS had found Tyer and used him as a model. To me it was the perfect model for series animation, and, no doubt under the influence of Ralph Bakshi they glorified their model.

It is interesting how many try to imitate the styles of all three and very few approach the level of any of them. I hope those imitators keep triying. To me, it’s the essence of 2D animation, and perhaps within this graphic medium one of those imitators will break through and we can relish such achievements. Achievements which are virtually impossible in the puppet-computer animation of Pixar and Dreamworks. But within that imitator, 2D animation will stay alive.

A couple of screen grabs were borrowed from the sites of

Thad Komorowski and Kevin Langley. My appreciation and thanks.

.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 8:18 am 1.Mark Mayerson said …

One similarity between Tytla and Scribner are that they both needed very particular environments in order to do their best work. Tytla needed characters with strong emotions. Once he left Disney, no other studio could provide him with that.

Scribner needed Clampett as a director. Clampett didn’t care about consistency in drawing or animation, he cared about the impact he had on an audience. As a result, he played McKimson’s and Scribner’s animation off each other, using McKimson for the subtle acting and Scribner for the wild and crazy scenes. Scribner’s work gained by being contrasted with calmer work around it, as it was a release of emotion and tension.

It’s interesting that McKimson didn’t seem to have a problem with Manny Gould. Gould’s animation was very broad, but he kept the characters on model. Scribner was broad in action and drawing, and I’m guessing it was the drawing part that McKimson objected to.

Tyer, by contrast, benefited from the apathy at the studios he worked at. He did what he wanted at Terry. Even when budgets were lower in the ’60s and he was working on TV cartoons like Felix the Cat and Snuffy Smith, he still worked the same way. Tyer was lucky in that he was self-sufficient, not needing a particular environment like Tytla and Scribner. Tyer could do his thing anywhere.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 8:26 am 2.Michael said …

Tyer could do his think anywhere, as long as he was left alone.

It’s interesting that his characters don’t distort wildly in Bakshi’s FRITZ THE CAT. He was given the film’s most emotional moment, yet he kept the characters tightly on model.

(I also knew he complained daily of the content of the film – he was a devout Catholic. One day, cursing over the material he was asked to animate, he got up from his desk and loudly quit. He didn’t come back.)

on 15 Mar 2011 at 10:31 am 3.Neal said …

Scribner did some great animation, but was not always “great,” nor right. VERY often self indulgent, sloppy, and lazy, he felt his work was more important than the films he worked on. I’ve found most people who blindly defend his work tend to be hacks who have no idea what they’re talking about.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 12:39 pm 4.Ray Kosarin said …

This is one of the most interesting posts I’ve seen in a long time. Every Clampett devotee (and that includes me–I’m just one of the quieter ones) should read this before they next kick up a ruckus.

Tytla, Tyer, and Scribner had an uncanny genius for seeing past the frame-lines and knowing, at a visceral level, how their drawings, accents, and distortions would play in sequence and be sensed by the audience. That they had this gift a good half century before video testing would make it vastly easier for an animator to experiment and test his work only underscores their brilliance.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 1:22 pm 5.Eric Noble said …

Interesting post. It’s a shame that McKimson just couldn’t understand what Scribner’s strength’s were. Then again, I don’t think there were a lot of people who did. I don’t think any of these men could work in today’s studio environment. They would be forced to pull back until there work was as bland as everything else.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 1:31 pm 6.Eddie Fitzgerald said …

Wow! A terrific post!

My favorite Tytla animation was the gentle giant in the Mickey and the beanstalk film. The giant had tons of personality and the distortions, which were amazingly smooth in the execution, underlined that personality and made the giant more appealing. I’m guessing that an awful lot of pencil testing was required to make it work, and probably nobody but Disney would have attempted it.

Tyer was a genius and I’m so happy that the studio tolerated him. I guess he turned out so much footage that they figured they couldn’t afford to lose him. Nowadays a maverick like that would find himself out on the street. What an odd time we live in. Artists will take drugs and listen to Nine Inch Nails, then when it comes time to animate they’re as hide bound as little old ladies.

Scribner was my favorite of the three, I guess because he was a great cartoonist as well as a great animator. Mark was right when he said that McKimson and Scribner made a good team (“team” is the wrong word, but it fits the point I’m trying to make) when they worked for Clampett. Sometimes McKimson would start a scene and Clampett would have Scribner finish it. I like the idea of teaming up animators with different strengths.

I agree that the kind of distortions you talked about are the very essence of 2D. 3D “puppet” animation didn’t compete with 2D and win. 3D competed with a desicated form of 2D, that had long since excluded the kind of innovators that had once been its life’s blood.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 1:40 pm 7.Michael said …

It’s amazing how even Georg Pal understood that the distortions were essential for animation to breathe. His 3D puppets – made out of wood – moved with all the plasticity of Scribner or Tytla (not animated as well, of course). If only cgi artists would look at those films as models since they’re making more malleable computer puppets. It’s certainly the route I’d take if that were my medium.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 1:41 pm 8.David said …

Very thoughtful analysis. Thank you.

(Michael, someone really should pay you to develop and teach a university course along the lines of “History and Technique of Character Animation” )

on 15 Mar 2011 at 4:06 pm 9.Eric Noble said …

“(Michael, someone really should pay you to develop and teach a university course along the lines of “History and Technique of Character Animation†)”

I would move to New York to take that class, along with John Hubley Abstract Concepts Class. I would love to have you as my teacher Mr. Sporn.

on 15 Mar 2011 at 6:14 pm 10.Stephen Worth said …

I’m actually a fan of Tytla’s work at Terry-Toons. It’s obviously not as polished, but it has energy to spare. There’s a Mighty Mouse cartoon where he gains his super powers by getting all liquored up that has a terrific drunk scene.

on 16 Mar 2011 at 12:35 am 11.J Lee said …

Tyer’s work while head animator at Famous is a little less arbitrary than his later efforts, because he was able to assign himself the broadest scenes in his cartoons that would lend themselves the best to the style of animation he was perfecting. In the case of the Popeyes usually that was the climactic end scenes, but not always — he gave himself the Averyesque sexual excitement reactions of Popeye and Bluto to Olive’s Samba dance in “W’ere On Our Way to Rio”, and the Irish cop being repeatedly nailed by the falling furniture in “Moving Awiegh”.

So Tyer knew how to use his own particular style best, and it was pretty much how Clampett was using Scribner during the same time period over at Warners. It’s only when he goes over to Terrytoons that his scenes during the cartoons become less centered on where his drawing style would be the most effective (though at Terry’s place it was often the case that whatever scene(s) Tyer did animate ended up being the most interesting thing about the cartoon anyway).

on 16 Mar 2011 at 7:17 am 12.Bob Jaques said …

Actually the reverse – Tyer gave himself the subdued scenes of animation in We’re On Our Way To Rio. Two in particular – when Popeye shies away from Olive and sticks his head out of his pants and when his heart beats out of his chest and he pushes it back. The Averyesque scenes cited by J Lee were animated by William Henning.

on 16 Mar 2011 at 1:05 pm 13.John V. said …

Uncle Eddie: Which giant are you meaning? Tytla animated the Giant from “The Brave Little Tailor” but he had left the studio by the time “Mickey and the Beanstalk” went into animation.

on 16 Mar 2011 at 4:47 pm 14.Eddie Fitzgerald said …

John, is that true!? I never looked it up, because it looked so much like something Tytla would do that I just assumed it was his. Geez, what a mistake! Thanks for the correction!

on 16 Mar 2011 at 6:33 pm 15.Michael Barrier said …

I don’t have a copy of the “Fun and Fancy Free” draft, but I took extensive notes from it at the Disney Archives, back in the ’90s, and my notes say that John Lounsbery animated most of the giant’s scenes. I don’t know how seriously that credit should be taken, since (as with “Mr.Toad”) animation began before World War II and was picked up after the war, and some people credited for animation may have been reworking other people’s scenes. I can’t recall running across anything to connect Tytla with “Mickey and the Beanstalk,” though.

on 17 Mar 2011 at 4:09 am 16.The Gee said …

Okay. You can say those three were superheroic in what they could do but why didn’t they a) pass it along, b) immediately influence others?

Was it partially or mostly because they got away with it? Like it was mentioned, Tyer’s footage helped with his job security.

As far as I know, not being a knowledgeable Disney-o-phile*, Tytla was Tytla. But, from what I know of his work he was Masterful and likely irreplaceable.

Scribner’s situation….whew. Not everything works out for the best and that sucks. I wish things had worked out well for him.

So, even if he was not the greatest director and most daring one, why was McKimson so uptight?

*that sounds wrong

on 17 Mar 2011 at 9:52 am 17.Michael said …

The Gee: You’re saying that Tytla was an artist who couldn’t be replaced; Tyer turned out a lot of work quickly; and Scribner, things didn’t work out for him.

I’m saying all three were artists and all three were irreplaceable. Picasso has lots of imitators, and they all look like imitators of Picasso.

on 17 Mar 2011 at 9:10 pm 18.Tom Minton said …

Why the three didn’t pass it along may be because teaching is a different skill than animating. Aside from artistic skill levels, some people are born communicators and others are inarticulate. The best teachers have a burning desire to communicate and share what they’ve learned. Can’t say that Scribner, Tytla or even Tyer really wanted to teach. They lived to animate, and animate their way. All three were, in their prime, very, very lucky.

on 18 Mar 2011 at 1:34 am 19.Eddie Fitzgerald said …

For Mike B.: Thanks! So the Beanstalk giant animation wasn’t Tytla, at least not the final version. If it turns out to have been Lounsbery then I have new respect for the man.