Books &Models &Story & Storyboards 07 Oct 2010 07:41 am

Backing Forward

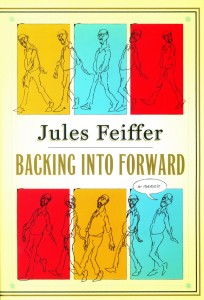

- I’m currently reading an excellent book; it’s Jules Feiffer‘s autobiography, Backing Into Forward. The book not only serves as Feiffer’s life story, it’s also a treatise on art, cartooning and illustration. The man’s led an extraordinary, artistic life from drawing his weekly strip in the Village Voice to writing plays and movies with the likes of Mike Nichols, Stephen Sondheim and other notables and actors.

- I’m currently reading an excellent book; it’s Jules Feiffer‘s autobiography, Backing Into Forward. The book not only serves as Feiffer’s life story, it’s also a treatise on art, cartooning and illustration. The man’s led an extraordinary, artistic life from drawing his weekly strip in the Village Voice to writing plays and movies with the likes of Mike Nichols, Stephen Sondheim and other notables and actors.

I’ve had the pleasure of working with Mr. Feiffer on several occasions, and I can attest that he’s as distinguished and constant an artist as I’ve met. I’ve also had the chance to interview him publicly about the Oscar for Munro (which he didn’t receive – William Snyder did) as well as his long working relationship with Gene Deitch. Mr. Feiffer is an erudite man, and it comes across in this autobiography.

The post that appeared yesterday on the ASIFA Hollywood Archive blog made me think about this short section of the Feiffer book, three pages which call to mind his short history at Terrytoons. The story is interesting, one which I closely relate to. Here is that story in Feiffer’s own words:

Eli Bauer (R) and Jules Feiffer (L) at Terrytoons.

- (R.O.) Blechman drew like no one else, in captivating minimalist squiggles that Deitch presented stunningly on a panoramic movie screen. A couple of days a week, Blechman and I found ourselves sitting next to each other on a wrong-way rush hour commute to New Rochelle. We would sound each other out on the business, whom we liked, whom we didn’t like, what we were going to be when we grew up. A modest man of considerable sweetness, it was surprising to find that Blechman was as dismissive as I was of the outdated but amiable hacks we had been shipped in to replace, a company of aging boys, midfifty to seventy, who were unembarrassed by and even took pleasure in their mediocrity. They could pushpin seventy-five to a hundred layouts on wall-length corkboard that showed cats and mice and ducks and pigs and elephants wreaking cartoon havoc on one another. Then, following the age-old tradition of storyboard conferences, they would mortifyingly act out in funny voices before sponsors, network honchos, and account executives what was plainly visible to anyone who could read.

A man of fifty had to bark like a dog, a man of sixty had to flap his hands and quack like a duck, a man on the verge of retirement had to jump up and down in mock excitement. All this to convey to clients what was assumed they couldn’t understand without the assistance of stand-up interpreters.

And as it must to all men with an attitude, one day it came to be my turn to humiliate myself. Gene Deitch had brought me into Terrytoons in part to design a three-minute animated story to run several mornings a week on Captain Kangaroo, CBS’s star morning children’s program. Deitch’s own creation for Captain Kangaroo, a popular series called Tom Terrific, was about to run its course. On the basis of my early Voice strips and Clifford, which Deitch remembered from the back page of the Spirit section, he thought I could design a sophisticated cartoon for lads in a UFA mode.

I went back to my Clifford roots and created a cartoon about a gang of street kids that I called Easy Winners. The title was derived from a Scott Joplin rag I happened to hear late one night on the radio. I put together a model sheet of characters and wrote and laid out a couple of episodes, one of which I pushpinned to the wall. The reaction was more than I could have hoped for. Everyone at Terrytoons loved it. The new guard loved it; the old guard claimed to love it, but it was hard to tell what they really thought, other than that they wished we would all go away.

Deitch was more enthusiastic than anyone, which was not a surprise. He was happiest working at fever pitch, his energy hyped into overdrive to convince the client, through sheer exuberance, that whatever doubts he might have about the work on the wall, it was potentially a classic. Gene loved my storyboard and he anticipated the excitement of the CBS executive (on his way at this very moment) who would shortly look at and decide the fate of Easy Winners. My role was to do no more than thousands of hacks before me: stand and perform the storyboard before Gene and a claque of animators and layout men, along with Bill Weiss, the president of Terrytoons.

The man from CBS arrived and my heart sank. He was a tall, silver-haired, mustachioed gentleman dressed in a three-piece pinstripe who, in dress and manner, made the rest of us in the room look inconsequential His name was Williamson, as English-sounding as his look. He outclassed us all, but Gene failed to notice. “You’re going to love this!” he squealed in his high-pitched salesman’s voice. One look at our distinguished visitor told me he was unlikely to love anything pushpinned to a wall in New Rochelle.

I had been through many of these storyboard sessions. I was upon the routine, but that didn’t mean I was up for the job. I was years away from public speaking, deep into shyness and self-effacement. Still, I did my best to sound like the quacking, barking, oinking animators I’d seen do this many times, pumping myself up to imitate a gang of five-year-olds from the Bronx. A minute and a half in, my humiliation was intense, and what was worse, it wasn’t getting me anywhere.

I had been through many of these storyboard sessions. I was upon the routine, but that didn’t mean I was up for the job. I was years away from public speaking, deep into shyness and self-effacement. Still, I did my best to sound like the quacking, barking, oinking animators I’d seen do this many times, pumping myself up to imitate a gang of five-year-olds from the Bronx. A minute and a half in, my humiliation was intense, and what was worse, it wasn’t getting me anywhere.

Behind me, Deitch and my claque had been laughing hystericalh until it became clear that the unsmiling Mr. Williamson was perhaps having himself a snooze. My approach shifted from manic to wistful. The claque’s laughter dwindled and died, leaving only my own strangled half laugh, half gasp.

Each time I turned from my storyboard, I noticed the room was a little emptier. My claque had decided that Mr. Williamson’s side was a better one to be on than mine. They had made the only sensible choice: I didn’t want to know me either.

By the time I limped to the end, only Bill Weiss, the president, and Gene, the head of the studio, remained, plus a goofily grinning threesome of loyal friends.

It was time for me to shut up and wait for Mr. Williamson’s decision on Easy Winners. His way of presenting it stays fresh in my mind fifty years later. After an uncomfortably long pause, he said, “Well, it’s a little New Yorker-ish.” Dead!

He had one final comment: “I mean, it’s closer to Dostoyevsky than it is to Peter Pan.”

As I headed home from New Rochelle that night, rage alternated with my sense of reawakened abandonment. Where had Deitch been when the time came to fight for me? I knew I had no call to be angry. Easy Winners was a loser. I gave them exactly what they wanted, but the they I gave it to was the wrong they.

I knew I was finished at Terrytoons, this studio where I had actually enjoyed a nine-to-five job for my one and only time since leaving the army. But it was no longer a place where my pride would allow me to work, a place where I could do quality work that also had commercial value. Seemingly, such a place did not exist.

In all the years I’ve presented storyboards, I’ve never done the song and dance required in animation studios. I’ve always trusted the material to out itself. This, perhaps, is a lesson I got while watching John Hubley pitch a storyboard, early on in my career. No quacking ducks, barking dogs or anything resembling the pitch meeting described here.

Thank you, Jules Feiffer, for leading the way and allowing me to feel less embarrassed about it.

on 07 Oct 2010 at 8:17 am 1.Stephen Macquignon said …

So are there some who still quack like a duck to sell a pitch?

Are some potential clients expecting “BING – POWâ€? Having someone act like a duck because the potential client doesn’t understand what is shown in a storyboard?

on 07 Oct 2010 at 9:44 am 2.Mark Mayerson said …

I’ve read the book and enjoyed it. Feiffer’s career is a lesson to all artists. He was adaptable and always managed to find a place where he could exercise his talents in service to his own interests.

The danger of barking and quacking in a pitch is that the performance will eclipse the material itself. Lots of projects have been bought based on a good pitch that the finished material couldn’t live up to.

on 07 Oct 2010 at 11:25 am 3.Tom Minton said …

I once asked Ralph Bakshi what he considered the most promising work he ever saw at Terrytoons. “Easy Winners”, he said. “Best thing they ever did!”

on 07 Oct 2010 at 1:14 pm 4.Eddie Fitzgerald said …

Nice article! Now I want to read the book! About pitches: a good pitch can sell a bad story, and a bad pitch can torpedo a good story. I never trust a pitch. I like listening to them because they’re so entertaining, but I never make up my mind about a story until I’m able to review the board when I’m alone with it.

The good thing about a pitch, apart from selling the project, is that it lets the boarder know where the story runs out of gas, or isn’t as funny as he thought. When you’re pitching to your peers it’s a good idea to talk to people individually afterward and ask where they thought the story flagged. Sometimes people are afraid to offend you, so you have to persist.

Occassionally you hear a pitch that’s so good, and has so many unique qualities, that you think the storyboarder had better take a shot at directing it himself. It’s a risk because shepherding a subtle and magical point of view through a real production system is perilous, even for the experienced, but it’s a great way to discover new talent.

on 07 Oct 2010 at 1:49 pm 5.Ray Kosarin said …

Pitching now seems a sad ordeal to everyone involved and a misguided way to find either the best properties or the best creators with the chops, discipline, and far-sightedness to sustain an idea, not for an energetic 20-minute dog and pony show, but for a production cycle of 13 to 26 half hours.

I hate to believe that so many acquisition execs are genuinely unable to read and assess the work on its own terms. Yet in more and more cases I worry that the endgame is less about acquiring the best properties for the network than a most rarified, expensive, and grossly irresponsible form of schoolyard bullying.

It might well seem that there is an endless supply of pitchmen wheedling to get themselves and their shows into their appointment books. But even for the exec who cares nothing for starting a working relationship with someone he or she should hope will be motivated to deliver their best work, weeding out all the potential shows save those hawked by those creators most willing to subject themselves to frathouse pandering and humiliations is also a most reckless way to serve the TV audience, and would-be sponsors.

on 08 Oct 2010 at 8:58 am 6.Dave Levy said …

There’s two conversations going on here.. Eddie is speaking of (correct me if I’m wrong) an internal storyboard pitch on a series in production, pitched by the storyboard artist to the senior creative staff. That’s the type of writing model they use on storyboard driven shows like SpongeBob, for example. Ray’s talking about (again, correct me if needed), a creator pitching to devt execs. Both are forms of selling, for sure.

I’m of the mind that most people hold themselves back very well (far better than any exec could block you) by not developing their own talents, not taking creative risks, not investing in their own projects, and so on. The worst gate keeper we face is always staring right back at us in the mirror.

Control the part of the equation you can control. I can’t make an exec a better person or have better taste, but I can work on myself.

on 10 Oct 2010 at 2:53 pm 7.gene schiller said …

“Closer to Dostoyevsky than it is to Peter Pan” – isn’t that a compliment?