Articles on Animation &Commentary 22 Jul 2009 07:12 am

Recap – theories

I’d written this a couple of years ago and posted it then, but I thought I’d expand on it a bit.

I have my own, odd thoughts about animators – great, master animators – these are the only ones I’m talking about.

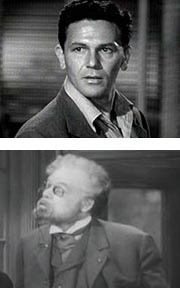

I think there are two types of animator. Both types, I think, are brilliant but I have my preference. Basically it’s the same breakdown I have with live action actors: the difference between Laurence Oliver and Marlon Brando. Both are geniuses, but I’d go out of my way to see one of them more than the other.

One works from the outside in, and the other works from the inside out. It’s Royal Academy vs. Stanislavsky.

Animators:

- One is a brilliant mechanic of an artist who gets every pose every gesture just right. The movement of the character is perfectly flawless, the accents are always in the right place, the timing is perfect, and the weight captured is exact.

The character is developed but usually in a manipulated, studiously planned way. Usually, this animation, to me, is cold. Give the character a fake nose, and Laurence Olivier could be playing it.

(Art Babbitt, at the top of the triangle, is to me the model for this type of animator.)

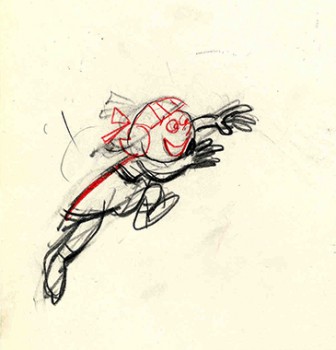

(Babbitt dwng of Mime from Hubley’s Everybody Rides the Carousel)

.

Then there is the emotional animator. The poses, gestures, actions of the character are emotionally executed by the animator as if this were the only way it could come out. The drawings are often violent and immediate – pencils ripping through paper and dark blotchy artwork.

This animator often puts emotion above mechanics, but (s)he digs to the depth of the part to find a real living thing. It isn’t always beautiful, but there’s a gem of a character on the screen. Like any living organism it’s unexpected and natural. Often this type animator works straight ahead (Does dwg#1 first, then #2,

This animator often puts emotion above mechanics, but (s)he digs to the depth of the part to find a real living thing. It isn’t always beautiful, but there’s a gem of a character on the screen. Like any living organism it’s unexpected and natural. Often this type animator works straight ahead (Does dwg#1 first, then #2,

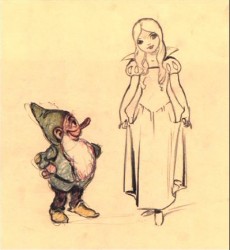

(Grim Natwick, to me, is the prime example of this type.)

No, I’m not saying if you draw dirty, rough, violent drawings you’ll be a great animator. I’m speaking somewhat metaphorically – although the two examples I gave actually did draw that way. I’m sure Art Babbitt did one or two rough,

(Grim Natwick drawing from a Mountain Dew spot.)________violent drawings in his life, but

__________________________________________________his animation feels tight, controlled, yet beautiful. Grim also did one or two clean drawings in his time – I have one, as a matter of fact, but his animation is controlled by his feelings, accumulated knowledge of craft, and emotions. It all feels immediate, spur-of-the moment. It’s alive!

I’ve only ever watched animated films with this guide going in the back of my head. Mind you, also, I have enormous respect for both of these types; it’s just that I prefer the emotional type. More than wanting my characters to think, I want them to feel.

My temptation, here, is to give the obvious list of animators and where they fall in my model, but I think for now I won’t. CGI also fits into this mold, but it’s not a great picture. I’m curious to hear what others think of this model.

- I don’t mean for this post to turn into a “praise Grim Natwick” nor a “put down Art Babbitt” statement. I hope it doesn’t read that way.

- I don’t mean for this post to turn into a “praise Grim Natwick” nor a “put down Art Babbitt” statement. I hope it doesn’t read that way.

As I’ve said in the past, I treasure the drawings I have that were done by Art. I study and love every frame of any piece he’s ever animated. I just have more fun, personally – and I underline that word, personally, reviewing Grim’s animation.

Marlon Brando wasn’t a better actor than Laurence Olivier. They just came at it from different angles, and my preference has always been the more natural side of the acting world.

Back in the late thirties when the Group Theater was formed, these actors went to Russia to search out Stanislavsky, an acting teacher who preached at the bible of natural movement – getting in touch with your inner soul to project through the acting.

Back in the late thirties when the Group Theater was formed, these actors went to Russia to search out Stanislavsky, an acting teacher who preached at the bible of natural movement – getting in touch with your inner soul to project through the acting.

On Broadway, recently, was a revival of Awake and Sing. Clifford Odets was a member of the original Group Theater, and his plays reflected their “common man” attitude to theatrical productions. They weren’t trying to do spectacles or Royalty plays, they were trying to project the “average Joe” back from the stage. It changed theater, created Arthur Miller and a whole breed of acting styles. Compare, ex-Group Theater performer, John Garfield’s performances of the thirties with someone who was praised to the hilt back then, Paul Muni. Completely different acting styles – one natural and one overemotional and unrealistic.

The same was and is true of animators’ performances.

At Disney’s, these guys took their animation seriously. Some, such as Fred Moore and Norm Ferguson, thought they had it right and continued their own paths. Some looked into Stanislavsky and rejected it; others adopted it wholeheartedly. Still others, such as Grim Natwick, did it naturally and always had. Just as in the theater.

At Disney’s, these guys took their animation seriously. Some, such as Fred Moore and Norm Ferguson, thought they had it right and continued their own paths. Some looked into Stanislavsky and rejected it; others adopted it wholeheartedly. Still others, such as Grim Natwick, did it naturally and always had. Just as in the theater.

Next time you look at Fantasia, try just watching the acting styles. There’s nothing more Stanislavsky than Bill Tytla‘s scenes in Night On Bald Mountain, and there’s nothing less Stanislavsky than most of the animation in the Pastoral sequence.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 8:58 am 1.Richard O'Connor said …

I see your point, but I think its a false parallel.

All animation, by necessity, is a akin to Olivier (or as some who worked with him told me he insisted, “Larry”).

It must be external and the poses must be clear in order to convey the emotion. If the gesture doesn’t work, the animation doesn’t work either (also a reason sound design is critical to animation in a way it is not to stage performance).

Stanislavsky demands “back story” and emotional triggers from the performer which are beyond impractical to the animator.

I do agree there is a distinction in the styles you present, but I’m not sure they don’t just represent points on a continuum of personal approaches to animation.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 9:13 am 2.Michael said …

Those “points on a continuum of personal approaches to animation” are the very difference in styles and emotional content. The preplanned key is the problem in many works depending on the inbetweener to fill in the holes between drawings.

A straight-ahead animator works completely by the seat of his(her) pants (even if it is mentally preplanned.) Drawings change violently as the progression moves ahead and allows for raw emotion to well up in burst out in the animator, as it does in the drawn animation.

Some animators work mathematically others work by instinct.

There’s a difference in the final results.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 10:35 am 3.Daniel Caylor said …

It’s almost as if I feel I have a choice in which path to go down. Emotional or mechanical. I know in the end it will just end up being whatever I am closer to by nature, most likely emotional.

Very interesting points. Richard does make a point as well. Stanislavski, to me, is just too much for an animator to put into his work. Having read three of his five books, there’s just too much there. An animator’s brain is already overflowing with all the thinking involved. I can’t see how anyone can contain/use all THAT information as well whatever else is going on in the scene. But this post does make me want to study Brando more, something I’ve been meaning to do.

Maybe you could extend on your theory by posting a list of animators and actors and their mechanical/emotion counterparts.

Hopkins strikes me as mechanical, Pacino emotional. Milt Kahl mechanical, Ollie Johnston emotional.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 10:38 am 4.Daniel Caylor said …

P.S

Interesting you pegged Tytla as Stanislavskyish, I’ll have to look for that.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 10:49 am 5.Michael said …

Tytla was, in many ways, the height of the Stanislavsky actor in the world of animation. I recently posted a scene’s drawings of Stromboli. If that energy doesn’t come out of the character (rather than the animator) I’m not sure it exists in animation. He then did the pure Stanislavsky dance of the devil in Bald Mountain and followed that up with the pure innocence of Dumbo running around his mother’s legs.

He animated forces within the body and then extended that to the skin of the character. He was an amazing animator.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 10:51 am 6.Jonathan said …

I disagree with Dick, character back story and emotional triggers are essential in animation to keep the acting from becoming clichéd and formulaic. Feeling comes from within a character, not by gesture alone. How can you create poses that are genuine and not cliché if they do not relate to that characters back story?

Also, movement and gesture (design) are essential to stage acting.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 11:15 am 7.Simon W-H said …

It is an interesting discussion point, but there are cross overs…Milt Kahl planned his scenes meticulously with thumbnails, he said he never really surprised himself much once he had the scene planned in this way, yet his articulation and performance were not intellectual in any way and his roughs were lively and beautiful. Kahl’s draughtsmanship was so strong that the struggle to realise on paper what he envisioned in his head was easier than it would be for less able draughtsmen. I don’t think this negates his deep feeling for what he was involved in drawing though.

Eric Goldberg doesn’t do thumbnails and his animation is flowing and beautifully articulated; accents hit perfectly, drawings clean, but loose and masterful. I think that Eric has a strong feeling for what he does but his technique is so facile that it would seem he does it without any creative struggle; yet there is an instinctive and deep understanding of the subjects he animates. If Eric were animating in the days of Fantasia, he would certainly have been better used on the Pastoral Symphony than on Bare Mountain but it would be interesting to see how he would handle something like the Devil in that sequence.

It is often down to casting that animators get bracketed as certain types. I remember seeing The Mission years ago and wondering whether it might have been a better film had the casting been swapped and Jeremy Irons been the soldier and Robert De Nero the priest…same with animators, I wonder how certain movies might have turned out had the casting of the directing animators been different. I know this strays rather from your original point, I agree that something from the guts effects us more immediately than more cerebral performances, I just think the edges are more blurred and that the two approaches tend to overlap.

on 22 Jul 2009 at 11:23 am 8.Ray Kosarin said …

A fine post, Michael, and Richard, you raise an important and most valid question–though I wonder if you and Michael aren’t actually rather closer in your opinions and understandings than you suggest?

You are of course right to remind us that animation depends on external clarity and strong poses–but so too would Method actors need ultimately to arrive at a performance that tempers the emotional route they took to arrive at it with the technical discipline to tame and focus it to connect with an audience. No doubt we would scarcely understand Brando’s first rehearsal of a script better than a lay audience would appreciate a Natwick rough; but those rehearsals and roughs are indeed not the product–only the means to it!

on 22 Jul 2009 at 3:25 pm 9.Richard O'Connor said …

You’re right, Ray. I think Michael and I are close in theory -just not terminology.

I just don’t think Method applies to animation -unless you go all the way back to the Stanislavsky of The Moscow Arts Theater. But that’s hardly the school that emerged from Strasberg and Adler into what we know today.

Method Acting demands the actor -first and foremost -experience the emotion of the character. How can an animator make someone cry if they themselves are in tears?

on 23 Jul 2009 at 11:56 am 10.John Celestri said …

A question: why is “naturalistic” acting considered better than “caricatured” (my term)? I have no doubt that Tytla could handle both…he just wasn’t cast in the more naturalistic roles. However, not only is his handling of baby Dumbo proof of his ability to be intimate, but if you look at the Stromboli scenes in which the puppet master is conducting his orchestra during the puppet performance onstage, you’ll see Tytla’s handling of Stromboli in a very subtle way, really getting into the music (hand gestures, facial expressions, etc.)…Stromboli is a secondary character in those scenes, but is masterfully animated.

on 23 Jul 2009 at 12:22 pm 11.Michael said …

I don’t see the acting by Tytla via Stromboli or the devil on Bald Mountain to be overdone or showy. They’re certainly theatrical (as a puppet master would be) and large (as the self-important satan might be), but they’re completely appropriate to their characters. Frank Thomas had a bit of this in him. I haven’t yet seen any of James Baxter’s animation that resembles anything I’ve talked about here. I’ll have to look deeper.

on 23 Jul 2009 at 2:36 pm 12.Richard O'Connor said …

While washing my shirts last night, thinking of Meyerhold and Stanislavsky and the Moscow Arts Theater the fight over “biomechanics” came to mind.

This was the true source of “Method” acting -coming of course from a starkly different tradition than the American stage. Meyerhold’s biomechanics would make for interesting application to animation.

on 26 Jul 2009 at 12:17 am 13.Thad said …

Interesting theory. I think you actually pegged the reasons why I don’t care for either animator you used for your examples. Art Babbitt’s stuff almost always feels mechanical to me, save Gepetto. I was told he actually used a ruler to animate. Grim Natwick seems to be revered but a lot of his stuff looks sloppy (save at Disney’s where I’m sure there was a major overhaul of cleanup and assistant work). Especially on things like the 30s Fleischer (obviously I am not impressed by his animation of Betty Boop) or 40s Walter Lantz cartoons, where everyone’s work was raw. Snow White and Rooty Toot Toot are probably the only things I’ve ever seen where his work actually looks good.

Bill Tytla is still pretty much ‘god’ as far as animators go, and could pretty much do anything. I think Walt sensed that too, which is why he wouldn’t take him back.

on 26 Jul 2009 at 3:12 pm 14.Steve Segal said …

I read that Ivan Pavlov & Sigmund Freud were contemporaries of Stanislavsky and it’s interesting that you can use a conditioned response to a stimulus to release subconscious memory to effect your performance. It all ties together.

Although a completely different quality of animator, I think Jim Tyer would be considered a method animator. He couldn’t stay on model but his work had energy and emotion.