Articles on Animation 18 Dec 2008 09:07 am

Spots – 1976

- Back in 1976 John Canemaker asked if I was interested in writing a piece on commercial studios for Millimeter Magazine. I was interested and took the job (while at the same time working at the Raggedy Ann studio.)

- Back in 1976 John Canemaker asked if I was interested in writing a piece on commercial studios for Millimeter Magazine. I was interested and took the job (while at the same time working at the Raggedy Ann studio.)

I found that commercial production was on a downswing and theatrical production up, keeping a lot of the smaller studios operating. That became my thesis for the piece, and I got in trouble for speaking my mind. One producer I praised said I was on his “s##t list” and I didn’t have to bother applying at his studio for a job. Since I had never sought work in his company, I found the thought amusing but was still confused that he’d found my article bothersome.

Looking back on the article now, I see that it was much ado about nothing; the article is and was harmless. However, it does give an overview of the commercial world – particularly in New York. Hence, I thought I’d entertain myself by posting it.

As much as 20 years ago, the animated commercial was fast becoming a viable art form. Bert and Harry Piels and Marky Maypo had already entered our lives via the television spot, and audiences waited through many an hour of mediocre TV presentations to be entertained by such characters in their one-minute commercial messages.

As much as 20 years ago, the animated commercial was fast becoming a viable art form. Bert and Harry Piels and Marky Maypo had already entered our lives via the television spot, and audiences waited through many an hour of mediocre TV presentations to be entertained by such characters in their one-minute commercial messages.

Commercial studios competed with one another to produce higher quality productions and more popular and entertaining films. The studios were major ones employing up to 75 people to produce their work. UPA, Academy, Storyboard, Pelican, and Elektra all existed with creativity and design strongly apparent in their storyboards and continuing right through to their finished product.

There was much experimentation in design and approach. The public readily accepted the new styles which they rarely saw or sought in theatres. (Even the trend setting UFA films of the early 50′s didn’t really receive audience acceptance till the arrival of these commercials.) The workers and producers alike took pride in their commercial product, and the results showed in the finished films.

Needless to say, many things have happened in the past 20 years. TV animation took a turn for the worse. Saturday morning, which had been filled with Mighty Mouse, Winky Dink, and Ruff and Ready filtered into a heyday for revitalized prehistoric monsters sliding across the screen with a superhero or two or seven talking for endless hours. Mind you, nothing moved but the sliding monsters and their mouths, but the networks bought it.

The animated commercial also took a nose dive. Individuals from these large studios began setting up their own one- or two-man studios. Their overhead was lower and, naturally, could come up with a lower bid for the commercials. The larger studios couldn’t compete with them and, as a result, became smaller. Dozens of people were thrown out of work. They were made to fight for freelance work from these small studios, change their careers midstream, or retire from their art. Many a good animator, assistant animator, inker or background artist was lost to the system. The result of underbidding was that the budgets never increased while the cost of animation became prohibitively expensive. The producers were forced to find new methods of presentation to stay alive in the commercial market.

The “classic” commercial became a rarity rather than the norm. Even the time allotted the producer to relay the message was reduced. The spots went from 60 seconds to 30 or even 20. The commercials, like Saturday morning TV, became limited in imagination, if not in animation. The agencies took charge of the writing for all campaigns, and more often than not creativity was lacking by the time the producer-had received the spot. There was too much concern for the statistics of the testing and too little concern for what was entertaining as well as selling. When the storyboard was lacking in creativity, even the most conscientious producer was able to do little more than contribute good production values to the finished spot. The spark had been eclipsed.

It is common knowledge that the film business, particularly animation, has had an inordinately poor first half of 1975. Many an animator, unable to find work at any studio, was ready to move for the sun and retire. There was just too little work on the boards. Agencies were looking for live action; a large number of spots were being sent out of the U.S., and a large number of non-union people were competing with and undercutting the established producers (the agencies didn’t seem to mind the cut in production values if they could get the spots done less expensively). With all of these problems apparent, it seemed difficult to imagine how a production house could, indeed, remain in operation.

Toward mid-year, a number of theatricals began to creep into production: THE METAMORPHOSIS brought a new company, San Rio, into being, while RAGGEDYANN AND ANDY brought a theatrical producer, Lester Osterman, into animation; Ralph Bakshi continued his films, COONSKIN, HEY GOOD LOOK-IN’, and THE WAR WIZARDS, while Alexander Schure brought his college, New York Institute of Technology, into production of the feature TUBBY THE TUBA; a third Charlie Brown feature began production at Bill Melendez’ studio, while the 24th feature, THE RESCUERS, began production at the Disney studio. Business in animation was returning to the theatres, just when it seemed that the animated commercial was hardly capable of supporting any studio.

The Hubley Studio, owned and operated by John and Faith Hubley, was formed from Storyboard, Inc., the company set up by the Hubleys in the early 50′s after John had left UFA and he’d met Faith. Storyboard’s commercial films were unique, clever and consistently high in quality. Marky Maypo’s dialogue still exists in the minds of most of TV’s first generation of viewers. The Hubleys used the commercials to pay for their theatrical ventures. Eventually, they moved almost completely to the production of these personal, theatrical films.

The most recent of these personal films is a 90-minute TV production, produced by CBS. Everybody Rides the Carousel is based on the writings of Erik Erikson, the noted psychologist. The film shows the development of a person in a society. This is, obviously, unique material for animation, not to speak of TV animation. It will be curious to see if any effect will be made on other animated programs.

The Peanuts specials, needless to say, have had a great impact on television animation, if not on all phases of American society. Bill Melendez runs the studio that has been producing these films. His studio has been operating for the last 12 years, but, obviously, never has it been so successful. There have been two feature-length films to spin off the very successful TV specials, and now a third theatrical film is in the works. Curiously enough, the few commercials that move through the studio are Peanuts-oriented. At the moment there are two spots being produced for Japanese television starring Charles Schulz’ characters. The studio, thanks to Peanuts, is able to keep a staff of, at least, 15 people on full time.

Most of the other commercial film producers are beginning to look into theatricals. Phil Kimmelman, producer and executive member of Phil Kimmelman & Associates, continued his use of noted designers (Jack Davis, Mort Drucker and Rowland Wilson, who has become an important mainstay of the studio, had designed ads and episodes of Scholastic Rock) when they commissioned Gahan Wilson to design a Halloween special for television. The prospect never passed the boarding stage, since the money ran out. They are still hoping for a backer.

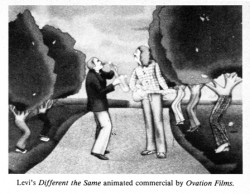

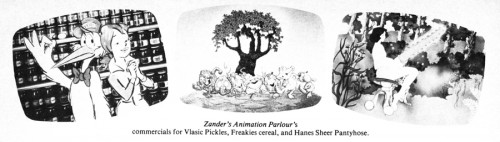

Other studios such as Zander’s Animation Parlour and Ovation, which normally produce only commercials, (Jack Zander had directed the TV feature The Man Who Hated Laughter, and Ovation is currently making a 10-minute industrial film) have said that they are interested in making theatrical films, but they want to be sure that the budgets are large enough.

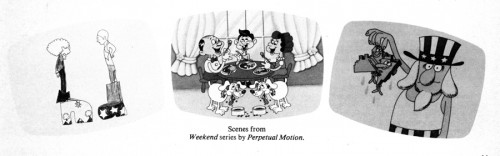

The problems involved in searching for theatrical films from the vantage point of a commercial film producer can be best illustrated by demonstrating the situation at Perpetual Motion. Studio heads Buzz Potamkin and Hal Silvermintz openly stated that they want to enter the theatrical market. They have been producing a series of low-budgeted spots for NBC’s network, late-night program Weekend. The show is aired the first Saturday of each month on NBC. Each program incorporates in its schedule one or two animated, editorial cartoons. These are usually satirical comments on some phase of the current news stories. Both producers enjoy doing these films since they’re given a freer rein than they usually have with the commercials. Stylization, story and design all combine to make miniature entertainment films for television. They would like to begin a longer film, but they want to make sure that it’ll be a project they’ll enjoy working on for the year or two it’d take to complete.

Buzz Potamkin left little doubt that he thought the animated commercial was far from dead. He stated that he expects this to be far from Perpetual’s worst year, however, if it weren’t for the Weekend spots and several jobs for NBC Sports (animated spots for Joe Garagiola’s pre-game show), the studio might have had a much poorer year. These short films allowed Perpetual to maintain a staff, however minimal.

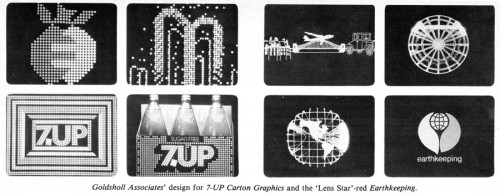

Morton and Millie Goldsholl are designers in the Chicago area who operate a studio which includes three full-time animators who are capable of table-top, stop-motion films, as well as cel animation. Morton Goldsholl states that half the studio’s film work is in longer films. They have produced a large body of work with some 12 titles listed among their experimental films. Much time is spent in experimentation, and, consequently, they have developed a “strange optical method” which is called “Lens Star.” The end result is a product which bears a resemblance to the “computer image” but, in fact, retains the warmth of the human touch. This method was used in a title to Earthkeeping, an ecology series. The 60-second title represents the beginning of life to the present ecological dilemma.

The Goldsholls seem to have touched on the best of both worlds, and perhaps this is actually what the majority of the commercial studios would like to strive for. They produce a number of commercials each year while still making the short industrial films. This has kept their studio very busy in the past two years.

Commercials, of course, have not disappeared, nor have they been as poor as this article might have led you to believe. There were a number of well-produced spots within this last year, and most of the studios can admit to a good second half of 1975. At the moment, several of the studios are at peak production.

Zander’s Animation Parlour is New York’s largest commercial producing studio. They are presently able to maintain a staff of 25 people to handle their film production. Jack Zander, a long- time veteran animator, heads the studio since 1970 when his studio, Pelican, closed. A large number of specialized commercial films are produced at Zander’s. The spots for Freakies breakfast cereal, animated by Preston Blair, have achieved quite a bit of success. Each eel is a major rendering effort, being prepared with colored pencils on colored paper and pasted to the celluloid sheets. The same method of rendering was employed in the most recent Vlasic Pickle commercials and the Hanes Sheer Pantyhose ads. The studio artists combined live-action with animation successfully on the spots for Dayton’s, a department store located in Chicago, and in an ad for Texaco.

Perpetual Motion has done a spot for Baggies which they are quite proud of. The commercial was designed by Hal Silvermintz. A recent AT&T corporate spot was designed by Guy Billout and animated by Vinnie Cafarelli and Vinnie Bell. Perpetual also has recently acquired the Schickhaus commercials, and for the past year, they have produced the Hawaiian Punch commercials. With these spots, they had a somewhat interesting problem: they were given an established character and design style and told to continue the series in the same vein. They’ve been successful.

Phil Kimmelman & Associates had a slightly different problem with the Cheeto’s Mouse. They were given these spots several years back. The client had been unhappy with the results he had received from other studios. Kimmelman has had the spots ever since. Bill Peck-man, a designer at the studio and a board member of the group, stated that these spots give them a chance to explore a bit with nuances in character. Since they’ve been handling the character for a while now, they feel that they can have some fun with him.

This is all quite interesting when you realize that they have just recently begun producing a number of commercials for Piels Beer which star Bert & Harry Piels.The studio has asked to continue the line of commercials done in the 50′s by UPA. The result was several 30-second spots starring the two characters (once again voiced by Bob and Ray). Kimmelman remarked that he found himself using several of the artists who had worked on the original films (Lu Guarnier had animated the spots at UPA in the 50′s and worked on them again in the 70′s). The only difference between these commercials and the earlier ones is that these are in color.

This is all quite interesting when you realize that they have just recently begun producing a number of commercials for Piels Beer which star Bert & Harry Piels.The studio has asked to continue the line of commercials done in the 50′s by UPA. The result was several 30-second spots starring the two characters (once again voiced by Bob and Ray). Kimmelman remarked that he found himself using several of the artists who had worked on the original films (Lu Guarnier had animated the spots at UPA in the 50′s and worked on them again in the 70′s). The only difference between these commercials and the earlier ones is that these are in color.

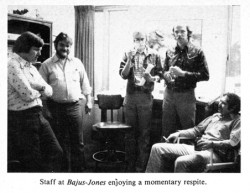

Bajus-Jones was formed six years ago in Minneapolis by Mike Jones and Don Bajus. The main office remains in that city, where some 14 people are employed. The studio has representatives in Chicago and New York, and some production is done in New York. Their work has principally been the making of animated commercials—recent commercial productions include a spot for Phillips Petroleum, and one for GMC Truck division— but they are now at work on a pilot for a feature-length film.

Ovation is owned and operated by Jerry Lieberman, Howard Basis and Art Petricone. Their most recent pride is for a number of spots just completed for Whitman’s Chocolate. The commercials, animated by Doug Crane, are done in the style of the sampler on the box of the chocolates. The end result is an animated crewel that is quite effective. Also of interest from the studio is a Clairol Herbal Essence spot which has a live-action figure walking through an animated garden of earthly delight. This is also the studio that did the campaign for Eastern Airlines. Each commercial incorporates a great number of animated figures. The detail is staggering.

Ovation is owned and operated by Jerry Lieberman, Howard Basis and Art Petricone. Their most recent pride is for a number of spots just completed for Whitman’s Chocolate. The commercials, animated by Doug Crane, are done in the style of the sampler on the box of the chocolates. The end result is an animated crewel that is quite effective. Also of interest from the studio is a Clairol Herbal Essence spot which has a live-action figure walking through an animated garden of earthly delight. This is also the studio that did the campaign for Eastern Airlines. Each commercial incorporates a great number of animated figures. The detail is staggering.

Several studios consider themselves, basically, graphic design studios. The work of the Goldsholls was previously mentioned, though indeed, their commercial work is outstanding. A recent one for 7-Up received well-earned celebrity among TV spots. Their Gillette Right Guard ads employed rotoscoped animation within the graphics. Just recently begun were two fully animated spots for Kellogg, which Morton Goldsholl feels will be a milestone for the studio.

George McGinnis and Mark Howard are the proprietors of the Image Factory. The two producers are designers who would like to see greater use of design and camera in animated films. This approach is, obviously, echoed in their film production. They’ve designed and directed the introductions for the five Mobile Showcase Presentations; (this included the famed TV productions of Moon for the Misbegotten and Queen of the Stardust Ballroom.) They’ve also designed the end logo used in the Metropolitan Life Insurance campaign. They’ve produced the Fall campaign for the CBS-owned and -operated stations. The two producers have a strong interest in moving toward more wholly animated projects, and their final goal will be reached when they can successfully see the combination of animated graphics with in-depth character animation.

George McGinnis and Mark Howard are the proprietors of the Image Factory. The two producers are designers who would like to see greater use of design and camera in animated films. This approach is, obviously, echoed in their film production. They’ve designed and directed the introductions for the five Mobile Showcase Presentations; (this included the famed TV productions of Moon for the Misbegotten and Queen of the Stardust Ballroom.) They’ve also designed the end logo used in the Metropolitan Life Insurance campaign. They’ve produced the Fall campaign for the CBS-owned and -operated stations. The two producers have a strong interest in moving toward more wholly animated projects, and their final goal will be reached when they can successfully see the combination of animated graphics with in-depth character animation.

Edstan is run by Stanley Beck and Ed Feldman. They are a graphics studio which will put the designs brought to them on film. They recently produced the graphics for NBC, CBS and Metromedia’s Fall campaigns. They also produced the opening graphics for the networks’ film programs. The studio has been in operation since 1959 and has produced a large number of network titles (most of the late night movie titles were produced at Edstan.)

With the Cheeto’s mouse, Freakies’ freakies, the Hawaiian Punch character, Vlasic’s stork, and the revival of Bert and Harry, it looks auspiciously as though animated commercials are turning toward the characters to entertain us. Perhaps this will be the trend; the agencies will spend more time caring about the viewer and a lot of good animation will come across the TV sets in America.

on 18 Dec 2008 at 10:21 am 1.Ray said …

A fun time-capsule, Michael–thanks!

Funny–I still remember some of those spots. Interesting to know Preston Blair did that (as I remember it) rather over-the-top “Freakies” ad. Funny, too, to think of the MGM cartoon studio as an old-boy’s network…

on 18 Dec 2008 at 11:33 am 2.Richard O'Connor said …

I looked up “eel animation”. Couldn’t find a clear definition -is basically what we’d refer to as “limited” animation?

Also, why UFA and not UPA?

The problem of getting “blacklisted” for writing about colleagues is something that creeps into my head whenever I publish something about contemporaries. I think it makes you more careful as a critic, that’s the positive side.

I can see why commercial studios would be uneasy about the article. They have to maintain the illusion that they’re so busy they have to turn away work -that helps justify prices and also make them sexy. Even though it praises the work, it punctures their mystique.

on 18 Dec 2008 at 11:52 am 3.Doug Vitarelli said …

Michael,

Great article. And very relevant to today’s animation scene. As a freelance 3D animator here in NYC I see a lot of similarities in the studio circuit that I travel today which you captured 30 years ago with one big difference.

And that is very few studios seem to want to do their own work but a lot of the more self motivated artists are creative outside of their paid gigs.

It’s a lot more fun hopping from studio to studio to meet and talk with the other artists and find out what they’re creating rather then the work on the actual job we’re all there for.

Paragraphs 4 and 5 really hit home with the market today.

on 18 Dec 2008 at 1:02 pm 4.Michael said …

Hi Richard, Of course you’re right about the errors. They scanned differently than they appeared in the magazine: “eel animation” should be “cel animation” and “UFA” should have been “UPA.” I corrected the original post.

on 18 Dec 2008 at 2:07 pm 5.Richard O'Connor said …

That’s funny. If you google “eel animation” there are some pdf’s that talk about Disney pioneering it.

I thought it was some secret technique I hadn’t heard of.

And maybe UFA was what UPA’s commercial division was called.

Reminds me of the David Mamet novel, Wilson, which takes place in the future after all information has been transferred to computers and then gets lost.

on 18 Dec 2008 at 3:47 pm 6.Michael said …

Of course, UFA was the great German film studio of the 20′s that produced most of the brilliant German Expressionist films and financed some exploratory animation by the likes of Oscar Fischinger. “Eel” animation sounds like it could be electric.