Articles on Animation &Independent Animation 25 Nov 2008 08:37 am

The New Animators of 1977

- Jenny Lerew reminded me, this past weekend, of Richard Protovin. Richard was an Independent animator and the head of NYU’s animation department from 1979-1988. In that position, he inspired quite a few people, and Jenny’s comment got me trying to remember where I saw an article about Richard.

I came up with this article by Thelma Schenkel from the animation issue of Millimeter Magazine in 1977. I got a kick out of revisiting this article and thought it definitely should be shared.

A new generation of American animators is coming into existence. Trained in art schools and college filmmaking programs, they are turning to animation on a scale unprecedented in independent American filmmaking of the past. Mainly in their 20′s and 30′s, they were brought up on comic and storytelling cartoons, but their films are rarely broadly comical, although they’re often very witty, nor are they illustrations for stories. They are staking out a new territory for animation, one that until recently was the province of the poet. Whether their films are erotic, whimsical, or abstract, they are all in some way exploring the inner landscape — feelings, the workings of the mind, the mechanisms of perception. Although the techniques they use vary widely, they all share in the poetic impulse — in the search for new expressions of personal visions.

Until fairly recently, only a few names came to mind when one thought of experimental poetic animation in America. Today, the ranks of talented young animation poets are growing. Despite the dearth of effective distribution channels and outlets, and the difficulties of finding time and mental space to make their “personal films,” while often supporting themselves by doing commercial projects, they are making some very exciting, extraordinary films. The following are only a few of the many talented young animation artists whose films merit being seen and re-seen, talked about, and written about:

ELIOT NOYES, JR. — Since Clay, made at Harvard’s Carpenter Center in 1964, Noyes has been dazzling audiences of all ages with his witty inventiveness, his bold handling of materials, and his humanism. In Clay, an 8-minute version of evolution, he spawns a universe out of a lump of clay with the playfulness of the ancient gods of creation. Noyes makes magic with the simplest materials: Alphabet (1966, Canadian Film Board) is drawn on milk-glass with felt-tipped pen; In a Box (1966), a tale of the barriers people and cities erect to keep out beauty and freedom, is drawn on paper; Sandman (1973) (Pictured below right) creates a dream world with an underlit handful of sand. His most ambitious film, The Dot (1975), combines live-action and animation in a half-hour allegory on the liberating

ELIOT NOYES, JR. — Since Clay, made at Harvard’s Carpenter Center in 1964, Noyes has been dazzling audiences of all ages with his witty inventiveness, his bold handling of materials, and his humanism. In Clay, an 8-minute version of evolution, he spawns a universe out of a lump of clay with the playfulness of the ancient gods of creation. Noyes makes magic with the simplest materials: Alphabet (1966, Canadian Film Board) is drawn on milk-glass with felt-tipped pen; In a Box (1966), a tale of the barriers people and cities erect to keep out beauty and freedom, is drawn on paper; Sandman (1973) (Pictured below right) creates a dream world with an underlit handful of sand. His most ambitious film, The Dot (1975), combines live-action and animation in a half-hour allegory on the liberating  power of the imagination — the animated dot becomes the catalyst that frees the “prisoners” from the confines of school and home. Constantly exploring new techniques, Noyes is currently completing Glove Story, using actors in combinations with video-animation, and Pitcher’s Feathered Bird, which experiments with chromakeying live actors into Noyes’ drawings. If his brilliant use of technique, his wit, and the humanism of his films of the last 14 years are any indication, we can look forward to an innovative, compassionate, and refreshing use of videotape when these tapes are released.

power of the imagination — the animated dot becomes the catalyst that frees the “prisoners” from the confines of school and home. Constantly exploring new techniques, Noyes is currently completing Glove Story, using actors in combinations with video-animation, and Pitcher’s Feathered Bird, which experiments with chromakeying live actors into Noyes’ drawings. If his brilliant use of technique, his wit, and the humanism of his films of the last 14 years are any indication, we can look forward to an innovative, compassionate, and refreshing use of videotape when these tapes are released.

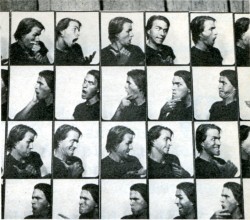

GEORGE GRIFFIN‘s self-referential films explore the tricky territory of animated illusion with marvelous wit and ingenuity. Paradoxical though it may seem, he often uses the most rudimentary of pre-cinematic toys — flip-books — to explore the most modern of ideas. Trikfilm No. 3 (1973), a complex orchestration of flip-pad metamorphoses alternating with the creation of the same sequences by the artist, combines live-action with animation, all the while delightfully fragmenting the illusion it is creating. The most elaborate of his “anti-cartoons,” as he calls them, is Head (1975), (pictured below left) an ingenious, witty essay on making filmed, photographed, drawn, painted, and Xeroxed images move.

Reverberating between multi-media versions of the same events, playing with disjunctions between figure and ground, Head is “a trick-film meditation on portraiture; the animator, as actor, lives through his drawings, which in turn become actors who influence his own self-image.” An insider’s diary on the process of creation, Head is a brilliant encyclopedia exploration of the circular relationship between the animator and his creation, of the nature of animated illusion itself. L’Age Door (1975), a one-minute flip-book film about a man and a door, shows what a witty intelligence can do with just a memo pad and a pen. His most recent work, View-master (1976), drawn in parodied cartoon styles, is comprised of 8 circular drawings with 12 characters in a run cycle on each drawing. The characters, including a troupe of dancing headless waiters and a selfpropelled shoe, chase each other around until the full circle of characters is revealed at the end — a contemporary Zoopraxiscope, with Eadweard Muybridge’s running man at the center, Griffin’s tribute to one of the greats of pre-cinema. In his witty elaborations on the simple techniques of pre-cinema, Griffin is unique among young experimenters in animation today. Informed by the refreshing playfulness of film’s 19th century origins, his films are very much of the 20th and even 21st centuries, in their incisive and witty insights into the nature of time, perception, and what we call “reality.”

Reverberating between multi-media versions of the same events, playing with disjunctions between figure and ground, Head is “a trick-film meditation on portraiture; the animator, as actor, lives through his drawings, which in turn become actors who influence his own self-image.” An insider’s diary on the process of creation, Head is a brilliant encyclopedia exploration of the circular relationship between the animator and his creation, of the nature of animated illusion itself. L’Age Door (1975), a one-minute flip-book film about a man and a door, shows what a witty intelligence can do with just a memo pad and a pen. His most recent work, View-master (1976), drawn in parodied cartoon styles, is comprised of 8 circular drawings with 12 characters in a run cycle on each drawing. The characters, including a troupe of dancing headless waiters and a selfpropelled shoe, chase each other around until the full circle of characters is revealed at the end — a contemporary Zoopraxiscope, with Eadweard Muybridge’s running man at the center, Griffin’s tribute to one of the greats of pre-cinema. In his witty elaborations on the simple techniques of pre-cinema, Griffin is unique among young experimenters in animation today. Informed by the refreshing playfulness of film’s 19th century origins, his films are very much of the 20th and even 21st centuries, in their incisive and witty insights into the nature of time, perception, and what we call “reality.”

KATHY ROSE‘s insignia is the remarkable cast of “characters” who people her films and who can be traced through The Mysterians (1973), The Moon Show (1974), Mirror People (1974), and The Doodlers (1975), all made at California Institute of the Arts. In The Mysterians, her silly-putty creatures, capable of any transformation imaginable, begin playing their surrealistic metamorphic games — which become more complex in Mirror People, as the figure-ground manipulations reveal space to be as much of an illusion as corporeality. To a sound-track of fun-house screams and cackles, Mirror People, a tribe of Halloween hallucinations, fuse into each other and get absorbed into their reflections and their environments in a universe where all is flux and nothing is stable,

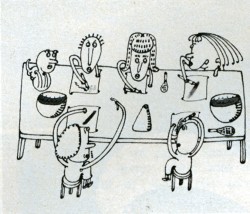

KATHY ROSE‘s insignia is the remarkable cast of “characters” who people her films and who can be traced through The Mysterians (1973), The Moon Show (1974), Mirror People (1974), and The Doodlers (1975), all made at California Institute of the Arts. In The Mysterians, her silly-putty creatures, capable of any transformation imaginable, begin playing their surrealistic metamorphic games — which become more complex in Mirror People, as the figure-ground manipulations reveal space to be as much of an illusion as corporeality. To a sound-track of fun-house screams and cackles, Mirror People, a tribe of Halloween hallucinations, fuse into each other and get absorbed into their reflections and their environments in a universe where all is flux and nothing is stable,  except for the constant delights of metamorphosis. The Doodlers (pictured Right) carries the game of illusion still further. Through Miss Nose and her clan of doodlers, whose curvilinear outlines and splashes of color come to life through a magic cat’s-tail brush, Rose makes some witty observations on the art of animation and on the symbiotic relationship between the artist and the characters. Although she was very excited by the films of Yoji Kuri, whose surrealistic pranks are echoed in her films, Rose’s characters have an indescribable uniqueness. It might have something to do with the way she draws them: all her characters are drawn upside-down. Yes. When she creates them, it is as if she wanted someone sitting on the other side of the table to be able to see them rightside-up, without having to turn the drawing around (of course, when they are filmed, they are rightside-up). She finds that it’s like “drawing with the eyes closed, you have one less level of consciousness.” But only the characters are drawn that way; the constant swirling changes of perspective, the simulated camera movements — all require tighter control and are drawn rightside-up. The battles and games between Rose’s characters are at some level intra-psychic encounters; she sees her characters as “parts of my unconscious” and is currently working on a film in which she and her characters confront each other. She feels that the new uses of animation have to be more than personal. They have to have an “inner truth about something real, a truth people can feel.” In their delightfully whimsical way, Rose’s films about the joys and struggles of creation succeed in conveying that truth.

except for the constant delights of metamorphosis. The Doodlers (pictured Right) carries the game of illusion still further. Through Miss Nose and her clan of doodlers, whose curvilinear outlines and splashes of color come to life through a magic cat’s-tail brush, Rose makes some witty observations on the art of animation and on the symbiotic relationship between the artist and the characters. Although she was very excited by the films of Yoji Kuri, whose surrealistic pranks are echoed in her films, Rose’s characters have an indescribable uniqueness. It might have something to do with the way she draws them: all her characters are drawn upside-down. Yes. When she creates them, it is as if she wanted someone sitting on the other side of the table to be able to see them rightside-up, without having to turn the drawing around (of course, when they are filmed, they are rightside-up). She finds that it’s like “drawing with the eyes closed, you have one less level of consciousness.” But only the characters are drawn that way; the constant swirling changes of perspective, the simulated camera movements — all require tighter control and are drawn rightside-up. The battles and games between Rose’s characters are at some level intra-psychic encounters; she sees her characters as “parts of my unconscious” and is currently working on a film in which she and her characters confront each other. She feels that the new uses of animation have to be more than personal. They have to have an “inner truth about something real, a truth people can feel.” In their delightfully whimsical way, Rose’s films about the joys and struggles of creation succeed in conveying that truth.

AL JARNOW‘s films, which seem to be playing with the malleability of perspectival logic, with fluctuations between the subjective and objective viewpoints, have a marvelous sense of spatial humor. At times reminiscent of Escher’s disorienting figure-ground enigmas, his films often lead us through an architectural nightmare (he studied architecture at Dartmouth), but manage, through the integrity of their visual logic, to create a spatial universe which seems to make perfect sense. Rotating Cubic Grid (1975) and Four Quadrant Exercise (1975) are marvelously precise architectural games, but Auto Song (1976), his most elaborate “story” film, pushes the play between subject and object the furthest. Drawn on index cards, it narrates the journey of an invisible eye (Jarnow’s) from its (invisible) reflection in the mirror of a VW bug, across impossible highways and oceans, up stairs and through tunnels, ending in the black hole of space. Purposely starting with a recognizable image set in recognizable space, the film very soon goes off into its own space which, because we have been well teased from the beginning, we accept without question. Jarnow’s latest film, Shorelines, combines objects (shells, stones), live-action pixillation, drawings, and Xeroxes. Although it represents a move away from the draftsman’s precision of the earlier films, it continues to play with space and perspective in Jarnow’s inimitable way.

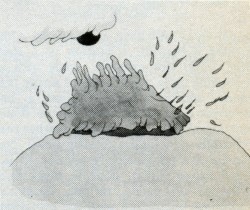

DENNIS PIES‘ early films, Nebula and Merkaba (both made at California Institute of the Arts in 1973), which he calls “experimental graphics,” already manifest his preoccupation with cosmic, mystical imagery. In Aura Corona (1974), he improvises a dance of two vertabra-like creatures which develope auras, depicting the delicate evolution of animate forms in a haunting, suggestive way. Pursuing his exploration of organic abstraction, in Luma Nocturna (1974), the “dark twin of Aura Corona” exquisitely nuanced crystalline textures float and fuse in a kind of lyrical, ecstatic cosmic dance. All done without the use of the

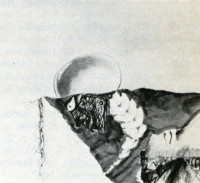

DENNIS PIES‘ early films, Nebula and Merkaba (both made at California Institute of the Arts in 1973), which he calls “experimental graphics,” already manifest his preoccupation with cosmic, mystical imagery. In Aura Corona (1974), he improvises a dance of two vertabra-like creatures which develope auras, depicting the delicate evolution of animate forms in a haunting, suggestive way. Pursuing his exploration of organic abstraction, in Luma Nocturna (1974), the “dark twin of Aura Corona” exquisitely nuanced crystalline textures float and fuse in a kind of lyrical, ecstatic cosmic dance. All done without the use of the  optical printer, the effects in Pies’ films are reminiscent of the work of Belson and Whitney, influences he readily acknowledges. He is currently working on Sonoma (pictured right) (an Indian word meaning “Valley of the Moon” — the general area in California where Pies lives), which deals with material from his journal of the last year. It is shot in 35 mm. color negative and is fully animated, “the full image in constant flux.”

optical printer, the effects in Pies’ films are reminiscent of the work of Belson and Whitney, influences he readily acknowledges. He is currently working on Sonoma (pictured right) (an Indian word meaning “Valley of the Moon” — the general area in California where Pies lives), which deals with material from his journal of the last year. It is shot in 35 mm. color negative and is fully animated, “the full image in constant flux.”

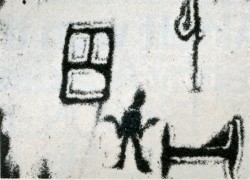

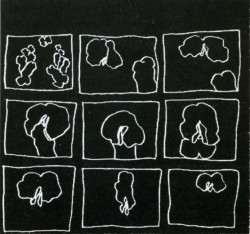

MARY BEAMS made her first animated film, Tub Film, in 1972 at Harvard’s Carpenter Center, where she now teaches. A whimsical view of a bath from a bather’s perspective, done in rough line drawings on paper, Tub Film ends with a slurp as the woman disappears down the drain,  after the cat pulls the plug. Seed Reel (1975), a series of 3 sexual haikus, is done in the same rough outline style: in “Hungry Poem,” (pictured Left) (reverse printed with white lines on black), a penivorous flower devours its mate and swells into a pregnant belly; “Sniff and Lick” portrays the encounters of some very erotic flowers, and “12 Dancing Penises” dance to the tune of “Turkey in the Straw.” In Going Home Sketchbook (1975) and Paul Revere Is Here (1976), she experiments with rotoscoping and shows her deftness in handling a technique that, in other hands, can become tedious, but which for Beams becomes an exciting way of recapturing the spontaneity of the hand-drawn image.

after the cat pulls the plug. Seed Reel (1975), a series of 3 sexual haikus, is done in the same rough outline style: in “Hungry Poem,” (pictured Left) (reverse printed with white lines on black), a penivorous flower devours its mate and swells into a pregnant belly; “Sniff and Lick” portrays the encounters of some very erotic flowers, and “12 Dancing Penises” dance to the tune of “Turkey in the Straw.” In Going Home Sketchbook (1975) and Paul Revere Is Here (1976), she experiments with rotoscoping and shows her deftness in handling a technique that, in other hands, can become tedious, but which for Beams becomes an exciting way of recapturing the spontaneity of the hand-drawn image.

ADAM BECKETT, of California Institute of the Arts, feels that “we are at the beginning of a wonderful golden age of animation”; his innovative, unconven-tional films will have a lot to do with making it happen. Evolution of a Red Star (1973), for example, made with a 6-drawing cycle which evolved under the camera during a 6-week period, is an excellent example of what can be done with a convention — the cycle — when the principles of painting directly under the camera are imaginatively applied to it. Flesh Flows (pictured Right) (1974), done in black line drawings on paper, reflects Beckett’s continued fascination with the

ADAM BECKETT, of California Institute of the Arts, feels that “we are at the beginning of a wonderful golden age of animation”; his innovative, unconven-tional films will have a lot to do with making it happen. Evolution of a Red Star (1973), for example, made with a 6-drawing cycle which evolved under the camera during a 6-week period, is an excellent example of what can be done with a convention — the cycle — when the principles of painting directly under the camera are imaginatively applied to it. Flesh Flows (pictured Right) (1974), done in black line drawings on paper, reflects Beckett’s continued fascination with the  evolution of polymorphous matter. Animated male and female body parts flow into, around, and through each other, evolving into proliferating, multiform creatures in a surreal pulsating dance. Beckett is currently trying to combine work on Life in the Atom (which he has been working on for 7 years), a new version of Dear Janice, and Knotte Grosse with his commercial work.

evolution of polymorphous matter. Animated male and female body parts flow into, around, and through each other, evolving into proliferating, multiform creatures in a surreal pulsating dance. Beckett is currently trying to combine work on Life in the Atom (which he has been working on for 7 years), a new version of Dear Janice, and Knotte Grosse with his commercial work.

RICHARD PROTOVIN‘s films have a naive, story-book quality about them which is definitely not what they’re about. This soft, innocent front, the delicate lines and candy-colored pastels, is an intentional disguise to arouse expectation for a simple story, expectations which he astutely manipulates for very different ends — “to turn things around, to go on the other side of the mirror.” Flamingo Boogy (1974), drawn on paper, starts out in a drive-in movie and ends up in a flock of flamingoes and winged turtles embracing the sun. The ocean itself is drawn into the sun in the mythical epiphany that ends the film. Everything flows and pulsates at the same time, disturbing movement echoing “opposites coming together in a spiritual union.” Heyzeus (1975), reflecting Protovin’s interest in Tantric Yoga, is an orgiastic dance of phallic and vaginal creatures which culminates in the creation of a

Left – Richard Protoviin/self caricature Right – “Flamingo Boogy”

mysterious bird creature exuding a powerful mystical energy. Like so many experimental animators, Protovin plays on the expectations associated with cartoons, only to turn them upside-down in an unexpected haunting way.

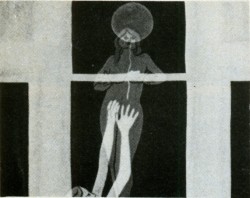

KATHLEEN LAUGHLIN‘s films explore a wide range of techniques: saturated color printing in A Round Feeling (1970), stop-motion single framing in Opening/Closing (1972) and Susan Trough Corn (1974). Her recent film Madsong (1976) (pictured Right) combines animation and live-action in a young woman’s personal everie on being female. With a polyphonic voice track (the woman’s inner voices echoed by the chorus of voices outside), it parallels the flow of her unconscious with the movement of the cycles of nature. In its artful use of live-action/animation overlap, which echoes the agitated flux of the voices of her mind from fantasy to reality, from “inside to outside, from backward to forward simultaneously,” Madsong is one of the few films about women today that succeeds in being intensely personal and univeral at the same time. Laughlin is currently working on a film about Meridel Le Seuer, a 76-year old midwestern poetess.

KATHLEEN LAUGHLIN‘s films explore a wide range of techniques: saturated color printing in A Round Feeling (1970), stop-motion single framing in Opening/Closing (1972) and Susan Trough Corn (1974). Her recent film Madsong (1976) (pictured Right) combines animation and live-action in a young woman’s personal everie on being female. With a polyphonic voice track (the woman’s inner voices echoed by the chorus of voices outside), it parallels the flow of her unconscious with the movement of the cycles of nature. In its artful use of live-action/animation overlap, which echoes the agitated flux of the voices of her mind from fantasy to reality, from “inside to outside, from backward to forward simultaneously,” Madsong is one of the few films about women today that succeeds in being intensely personal and univeral at the same time. Laughlin is currently working on a film about Meridel Le Seuer, a 76-year old midwestern poetess.

MAUREEN SELWOOD — The delicate lyricism of Maureen Selwood’s style is already evident in her first film, The Box (1969), which combines live-action and animation in a lively fantasy of the Astor Place cube sculpture coming to” life. The Six Sillies (1971), made at New York University’s Institute for Film and Television, in 35 mm eel animation, is rich with the luscious color and delicate Matisse-like line that evolve in the public service and commercial projects she has done since then.

MAUREEN SELWOOD — The delicate lyricism of Maureen Selwood’s style is already evident in her first film, The Box (1969), which combines live-action and animation in a lively fantasy of the Astor Place cube sculpture coming to” life. The Six Sillies (1971), made at New York University’s Institute for Film and Television, in 35 mm eel animation, is rich with the luscious color and delicate Matisse-like line that evolve in the public service and commercial projects she has done since then.

In her current project, Odalisque (pictured Left), she moves away from story-tellling into poetry; a series of mythical women undergo the most extraordinary transformations — the kinds of dreamlike metamorphosis that Selwood’s lyricism brings to life beautifully.

The short post script as to where are they now is not going to be written by me. I know that a couple of these people have died (Richard Protovin & Adam Beckett), several are still animating (Dennis Pies and Eli Noyes are both in California), others are animating and are connected with excellent schools (George Griffin teaches at Pratt, Maureen Selwood at CalArts). I believe Al Jarnow still lives in NY state, and the last I heard of Thelma Schenkel, she was teaching at Baruch College in NY. I’m not sure of the rest.

If any of you reading this know more, I urge you to let us know in the comments section or I’ll be glad to write a more extended piece in the future. I’m already thinking about some of the Independent animators from 1977 who were left out of this article.

on 25 Nov 2008 at 11:03 am 1.Tim Rauch said …

Dear god, your splog is like the animation schooling I never got fed to me on a daily basis. Actually, it’s better than that, it’s the awareness of all things animation and all things immediately peripheral to animation which you will hopefully continue to share for years to come. You’re my favorite “professor”, thanks!

on 25 Nov 2008 at 9:13 pm 2.John Schnall said …

Richard Protovin was an amazing teacher. I was lucky enough to be in his class in the late 70′s/early 80′s. He didn’t just teach technique, he inspired; he got the us to think just as much about the space around our drawings as about the drawings themselves, he stretched our minds. Thanks for posting this, Michael.

on 26 Nov 2008 at 11:07 pm 3.Sky David said …

The entirety of your “splog” has to be the greatest HISTORY OF ANIMATION. And here this forgotten piece from Talia Schenkel for all to see. Michael your intelligence gathering for our great art is pure magic. With each new addition I think: “How and where did Michael find all of this!” This should be the source point reference of all animation students today. If anyone knows how to contact Talia, I would love that information. She was teaching at Baruch College on my last contact. She visited in Santa Fe in about 1995 and I took her out to see the vast expanse of space of New Mexico, but over the years contact faded.

on 28 Nov 2008 at 2:03 am 4.George Griffin said …

Great animation archeology, Michael! I remember Richard’s enormous well of enthusiasm. He was a very generous artist and teacher who championed concepts like collaborative films and figure drawing sessions which were actually radical at the time. I do know some of these artists and pieces of their stories since the late 70s, but it might be better to hear from them directly so the facts don’t get distorted. For example, I know Al and Eli are doing interesting things (programming interactive museum exhibitions and producing animated features respectively) but I’m sure to get all the details wrong, especially what happened inbetween 1977 and now.

GG

on 10 Dec 2008 at 7:26 pm 5.Brendt Rioux said …

Hey, I just wanted to offer my thanks for the posting of this article. This school of 70′s independent work is the subject of my undergraduate thesis project, and your reprinting of this article adds to my pool of information. Keep this stuff coming, Michael, and thanks a million!