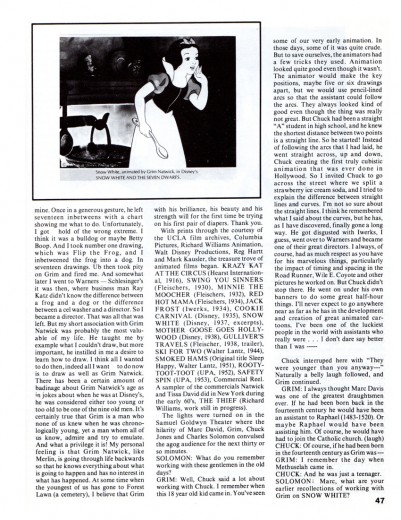

Monthly ArchiveJuly 2011

Disney &Frame Grabs 11 Jul 2011 06:43 am

Snow White Multiplane – 1

- The first feature Disney used to display his multiplane camera was his first feature, Snow White. Interestingly enough, I find the use of the camera in this first feature film to be one of the least ostentatious of them all. Any displays of depth or multiplane pans are almost hidden in the movie, as if they didn’t want to call attention to themselves. This, of course, is the exact opposite of its use in Pinocchio.

However, there are a lot of scenes that use it to hide or help effects for the film.

I’ve captured a lot of demonstrations of the camera in use and will start displaying them from the beginning of the film.

1a

1aThe film starts off using the multiplane with the first two shots.

1b

1b

As we truck in on the castle, there are slight changes of focus on overlays.

2a

2a

The same goes for this second shot.

3a

3a

In the wishing well, the brick work is broken into a number of different levels.

The top two are progressively out of focus even though there is no camera move.

3b

3b

This makes the ripples and the reflection easier to produce

keeping everything else in the same level of focus.

4a

4a

Once the woodsman takes Snow White to the forest, the camera

comes into its own – although they still use it with great subtlety.

4b

4b

As the camera moves in there’s a rack focus on all the levels.

4c

4c

The grassy hill that SW stands on moves separately from the sky.

5a

5a

And once the hunter tells her to run away there’s plenty of movement.

Here, she starts backing away from the hunter.

5b

5b

She continues to back away. Levels start moving behind her.

5c

5c

Once she starts running a large out of focus tree sweeps across the screen.

5d

5d

She moves into the perspective as the trees swoop past her.

5e

5e

She runs toward a block of trees.

5f

5f

We see her continue past the group of trees into the darkness.

At times she’s completely shaded by the out of focus trees.

6a

6a

She turns and backs slowly into the forest . . .

6b

6b

. . . and falls into a hole.

6c

6c

The camera holds for a beat on the hole in the ground.

6d

6d

Followed by a very fast pan down, trying to follow her.

Levels fly by out of focus.

6f

6f

We catch up to her holding onto a vine above water.

7a

7a

A quick cut back to reveal the environment.

7c

7c

She’s frightened by two logs that look like alligators.

8a

8a

Cut with her running out of the water.

8b

8b

Out of focus shrubbery blocks our view of her.

8c

8c

She continues moving under the shrubbery.

8d

8d

She finally comes out of the hole.

9a

9a

Frightened by the trees she runs forward screen right.

9b

9b

Cut as she enters large from screen left.

9c

9c

She runs into the perspective. Different levels of soft focus.

10a

10a

She’s frightened by eyes and falls to the ground.

In this shot the eyes seemed to be burned in on a second pass.

As the camera moves out, they don’t move at the same rate

causing some slight gliding.

10b

10b

Overlay trees slowly move into the frame.

The lighting of the scene brightens.

10c

10c

Finally, we’re settled watching her on the ground

surrounded by innocent pastoral animals.

11

11

Snow White on the ground with all the animals

does not employ the multiplane camera.

12

12

However, we immediately see a deer over a waterbed surrounded by trees.

This does use the camera to place the water effect in among the foliage.

There are plenty of shrubs out of focus above the water.

13a

13a

The same goes for this shot of raccoons.

13b

13b

The raccoons run out in the pick up of this shot, and we truck in to a turtle.

The multiplane level of the water separates from what’s under it.

14a

14a

Snow White is led by the animals through a wooded area

filled with multiplane levels.

14c

14c

The water effect has a level all its own.

14f

14f

How more apparent is the multiplane level than this one

that blurs out in an area that visually cuts off her head.

15a

15a

Snow White comes out to a clearing and is pulled to screen left.

15b

15b

Plenty of objects pass in soft focus.

15d

15d

The animals open to a clearing.

15g

15g

There’s a light change as Snow White views out . . .

16

16

. . . to see the dwarf’s house. No camera move, but the

multiplane still is used to create a feeling of depth.

17a

17a

A few shots later, Snow White runs across a little foot bridge.

17b

17b

She heads for the dwarf’s house.

17c

17c

Out of focus trees pass over her and the animals.

Photos 10 Jul 2011 08:11 am

Outdoor Sculpture

- I like recording some of the outdoor sculpture I come upon in my travels around NY. And, for better or worse, I’m gonna share a couple of pieces with you here.

1

1Madison Square Park has had this enormous, Asian face on show in the “Great Field.”

It almost makes this photo feel as though it were a squeezed Cinemascope image.

2

2

The luminescent quality of the stone makes me wonder

if anything is projected on this face at night.

3

3

The sculptor, Jaume Plensa, created the 44′ face as an homage to “everyday people.”

The artist’s website states that the dream-like monolith “aims to introduce a quietness

to the park, allowing viewers a moment of serenity and reflection in the heart of the

city that never sleeps.â€

4

4

I love that the face is constructed in levels, like brickwork.

It’s actually white fiberglass coated with a gel.

1

1

Moving up town to Park Avenue and 57th Street. some roses

have been on display since the winter. These are large things

that, to me, aren’t very attractive.

2

2

They’re sculptures by artist, Will Ryman, whose gallery

arranged for the Park Ave. display from Jan through May.

4

4

Several street corners from 57th St. thru 67th St. have different roses.

Some that lay on their side, some that stand up.

1

1

Down town, on 32nd Street and Park Avenue, there’s a big, stone statue

that is covered by a construction site’s scaffolding. You can only notice the

sculpture if you’re walking past it. Even then, you have to pay attention.

2

2

I took these pictures when it was gray and raining out.

At least, the sculpture stayed dry.

Just outside of Washingon Square Park there’s a mall of a street

filled with small shops and restaurants, LaGuardia Place. Among and

in front of theses shops is a statue of Fiorella LaGuardia, the mayor of

New York from 1934 to 1945. The statue is by sculptor Neil Estern.

LaGuardia was that he read the Hearst comic strips, “Puck, the comic weekly,”

on Sundays over the radio. An odd little fact that Chuck McCann told us in

his weekly Sunday kiddee show in NY during the 60′s.

I love this statue. It’s not very large and leads me to think that LaGuardia was a

short guy. I don’t know if that’s true, but that’s an impression I take with me.

Animation &Books 09 Jul 2011 07:12 am

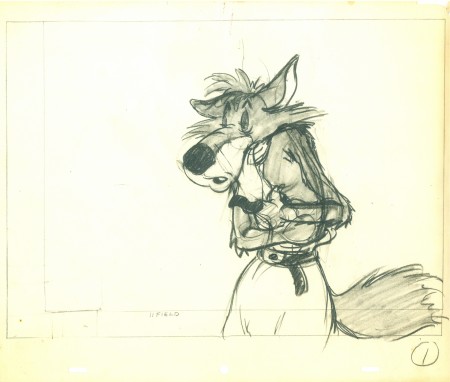

Tytla, Celestri, Anik and Eric Larsen

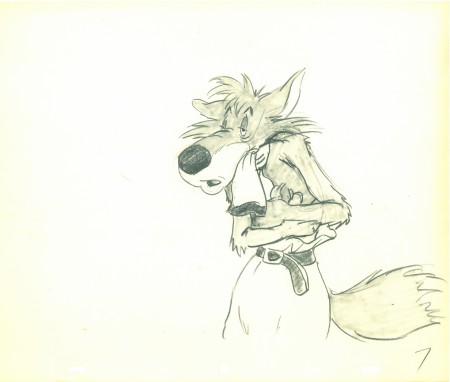

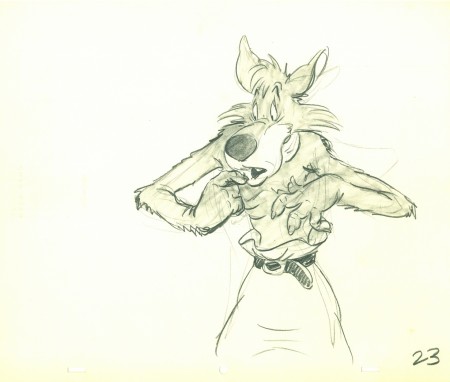

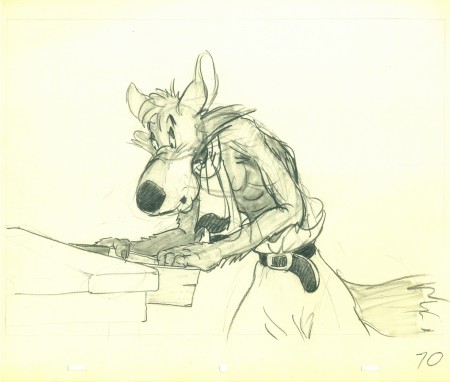

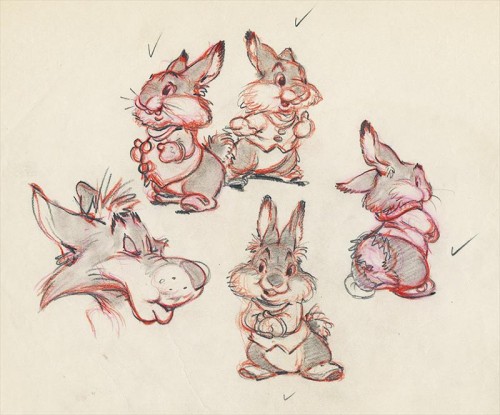

- Mark Sonntag just sent me a model sheet from The Hungry Wolf that he found on auction at Howard Lowery’s. There’s no way to tell if these drawings are by Tytla, but the drawing is beautiful just the same. The inclination to shade in the characters on this film is interesting, though. Many thanks to Mark for sharing.

______________________________

- I am such a fan of Bill Tytla‘s work, I can’t even begin to tell you how much. This week, on his blog, Andreas Deja posted some roughs by Tytla and I couldn’t believe how wonderful some of those drawings are.

- I am such a fan of Bill Tytla‘s work, I can’t even begin to tell you how much. This week, on his blog, Andreas Deja posted some roughs by Tytla and I couldn’t believe how wonderful some of those drawings are.

There’s a series of Grumpy posing in the middle of one of his negative rants, that just sends me. I’ve gone back to the blog at least a dozen times to look at those drawings again and again. The character starts by throwing all of his hostility out to whomever he’s talking to. Then he crosses his arms, with back to the listener. That immediately has him reach out to that person with his entire body, even though his arms stay crossed. It’s such a wonderful mix of emotions so beautifully and graphically presented. All the emotion within Grumpy is out on the floor; he thinks he has nothing to hide and is letting it all out. Thanks to Tytla, we see that Grumpy wants to be like all the others and love Snow White as well. He’s so conflicted and trying so hard not to be honest. This is a brilliant animator at the top of his game.

In the past, I’ve posted quite a few Tytla drawings – most of them loaned to me by John Canemaker. I think in the next week or two I’m going to pull out many of them for a recap. They’re just too great to sit hiding in the morgue of my blog. I want to take another look at them, and maybe share that, again, with you. I hope you’ll indulge my obsession.

- John Celestri is a very good animator who has been a fan of Tytla’s work since I first met him back in 1977 on Raggedy Ann & Andy. John was in the NY Assistant pool that I supervised, and he was a talent to reckon with. Now, John has a new blog that is starting to take shape. It’s like many animator/director blogs in that it’s built around his work in the industry, and there’s a lot of experience for him to draw on. After he left Raggedy Ann, John moved onto Tubby the TUba at NYIT, then Nelvana to work on Rock & Rule. From there he worked on many features in LA, some with Richard Rich‘s studio for Nest Animation. In every step forward, John’s animation kept getting stronger. Now he has his own studio in Kentucky.

- John Celestri is a very good animator who has been a fan of Tytla’s work since I first met him back in 1977 on Raggedy Ann & Andy. John was in the NY Assistant pool that I supervised, and he was a talent to reckon with. Now, John has a new blog that is starting to take shape. It’s like many animator/director blogs in that it’s built around his work in the industry, and there’s a lot of experience for him to draw on. After he left Raggedy Ann, John moved onto Tubby the TUba at NYIT, then Nelvana to work on Rock & Rule. From there he worked on many features in LA, some with Richard Rich‘s studio for Nest Animation. In every step forward, John’s animation kept getting stronger. Now he has his own studio in Kentucky.

The blog, at present, uses John’s own work to show basic animation techniques and script writing problems. It’s growing up into something quite interesting, and I suggest you check it out, if you haven’t already.

By the way, I love that John has pursued a completely non-animation, secondary path in his life. He has also authored quite a few mystery novels with his wife, Cathie. (Their joint site is called CathieJohn.)

- Also worth visiting is the studio site for Dancing Line Productions. This is the animation company of Anik Rosenblum, a Vancouver, Canada animator who brings a lot of grace and lyricism to the animation he’s been doing for some beautiful spots. There are many examples of his work on the site, and you should take a look at some of it.

Below is an animated piece called “The Autumnal Walk” which gives a good idea of Anik’s work.

The Autumnal Walk

This is one of my favorite pages of Dancing Line’s site. It answers the question, “Why hire us?” Anik has a good, sweet sense of humor. More power to him; I hope his company is successful.

- I just read an interview with Eric Larsen in Don Peri‘s book, Working with Walt. Something Eric said caught me and I thought it would be good to quote him:

- When I came into this business, Frank [Thomas] and Ollie [Johnston] and Marc Davis and Ward Kimball and John Lounsbery all came about the same time. Hal King and a few more came then, too. There was a group of us who developed, and Walt started putting a certain’ amount of responsibility on us in a way. But we came through what we called me unit system: each one of us came up through a very strong animator. These are the men I spoke of a little while ago when I said that here were such great talents and yet they opened up their arms to you to let you have everything they had: Ham Luske, Norm Ferguson, Bill Roberts, Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Freddy Moore, and then just a little bit later Bill Tytla. Good gosh, what more could you ask for! We came up under those men, being taught, you might say, with them looking over our shoulders. A number of years ago, we dissolved the unit system. Don’t ask me why because I can’t answer. It’s the biggest mistake we made. Now we are trying to set up units again. Like on Bambi, I had ten animators plus all their assistants

working with me. I spent most of my time up here in this room and then would go down and animate at night. But you could keep control of certain things. You learn by working with somebody who has gone I tough the mill. But you’re always learning. There’s no such thing as I graduation in an animation class.

Basically, Eric Larsen is saying that only by our working together can we advance the art of Animation. That’s true. But I wonder if we do that anymore. I wonder if we’re open to each other to try to help out. I hope so. I hope all these new sites, such as John Celestri’s site, help to impart some tidbit of knowledge to someone coming up. It’d be great if it does.

Bill Peckmann &Comic Art &Illustration 08 Jul 2011 06:58 am

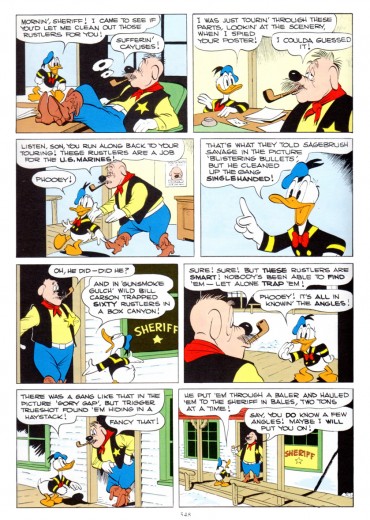

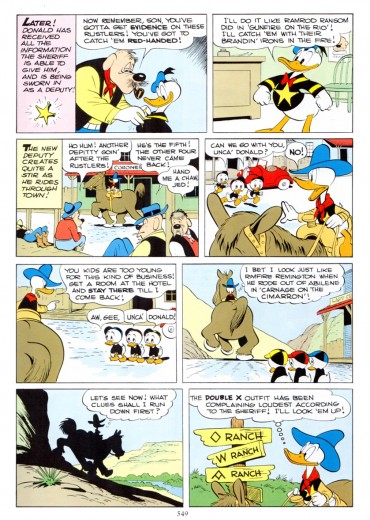

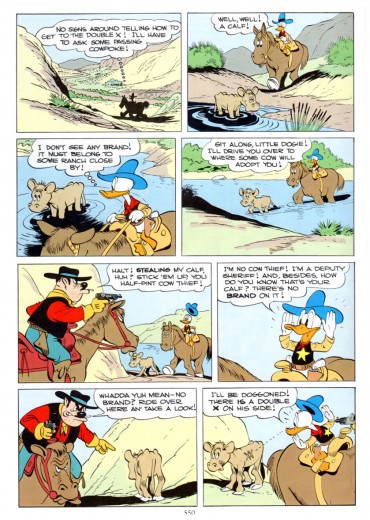

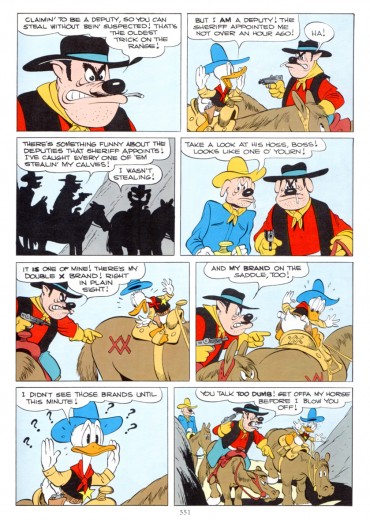

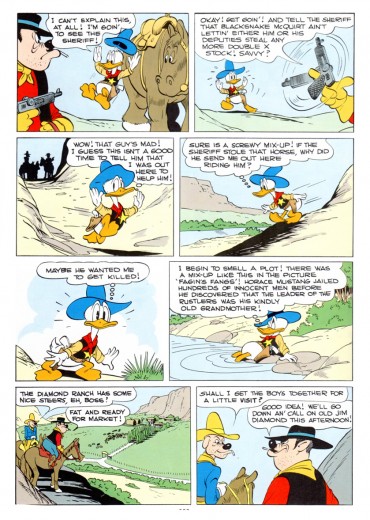

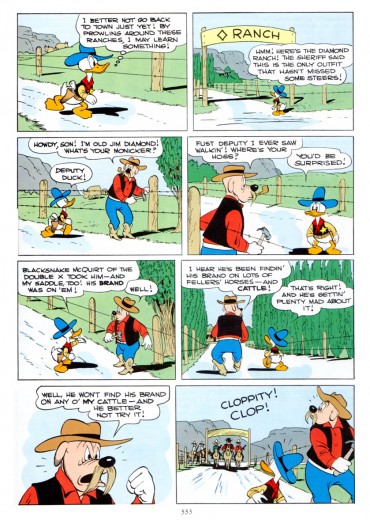

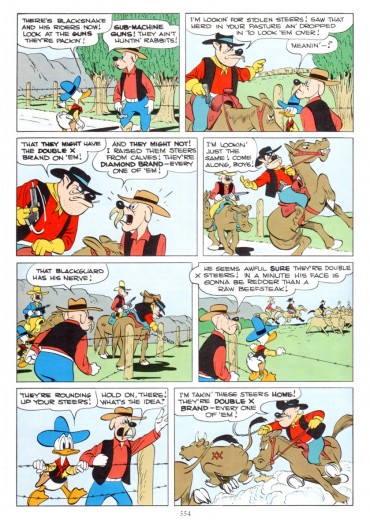

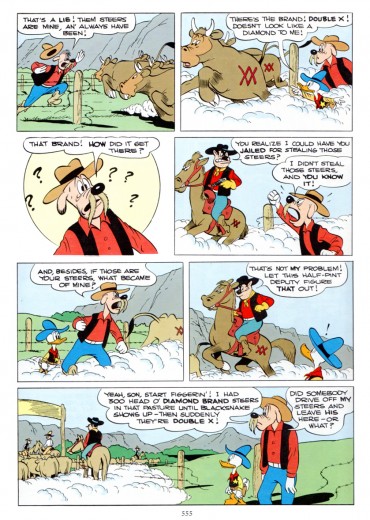

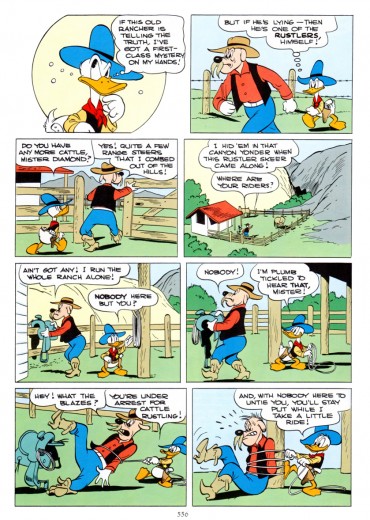

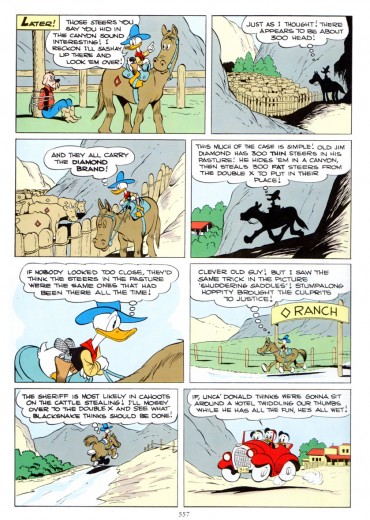

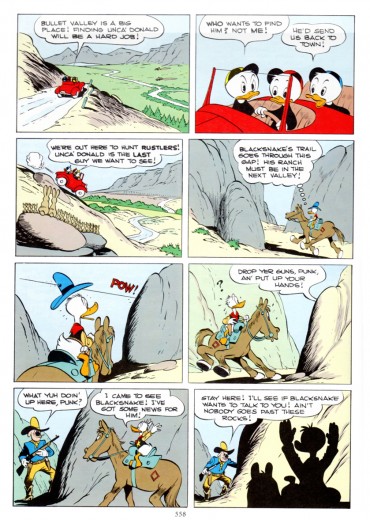

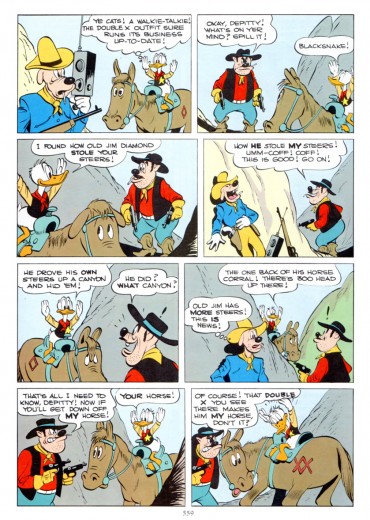

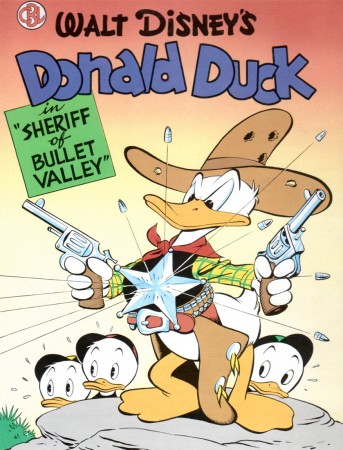

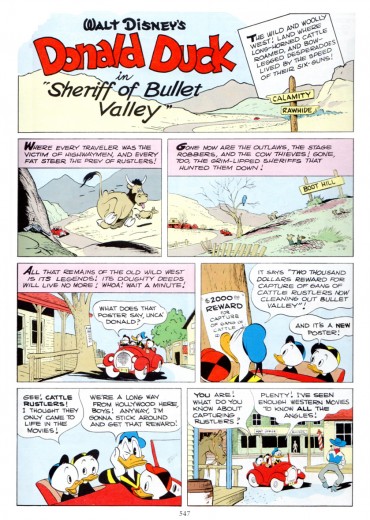

Sheriff of Bullet Valley – 1

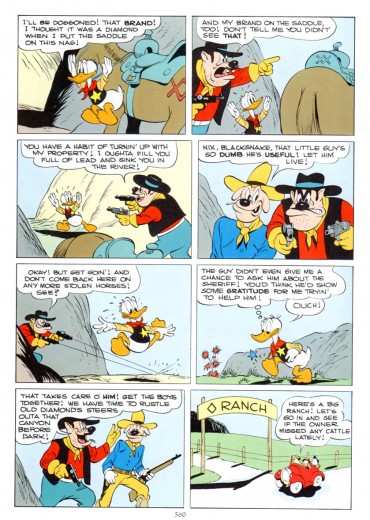

- Bill Peckmann sent me the first installment of Carl Barks‘ comic story, “Sheriff of Bullet Valley.” There will be two other installments to follow. Here’s the note Bill sent with the scans:

“Sheriff of Bullet Valley” was reprinted in Another Rainbow Pubishing Company’s “Carl Barks Library” in 1984. Most of the “CBL” was printed in B&W, fortunately “Sheriff” was printed in color and what a beautiful job they did. The coloring is done in wonderful flat tones, no color gradients and that seems to be just what the doctor ordered for Carl’s style.

“Sheriff of Bullet Valley” was reprinted in Another Rainbow Pubishing Company’s “Carl Barks Library” in 1984. Most of the “CBL” was printed in B&W, fortunately “Sheriff” was printed in color and what a beautiful job they did. The coloring is done in wonderful flat tones, no color gradients and that seems to be just what the doctor ordered for Carl’s style.

Barks’ was at the top of his game when he did this story and because of that, a great deal of enjoyable time can be spent studying each page and each panel. A lot of people have explained Carl’s art much better than I can, but to me, he always had the ability (and still does) to make a world on the printed page as real as the one outside your window. What he packed into those pages by way of writing, continuity, panel and page design, backgrounds and landscapes, his posing and the acting ability of his characters, wow,in this day and age it seems like such a super human effort.

Here then is the first installment of “Sheriff of Bullet Valley” by Carl Barks.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

To be continued

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &John Canemaker 07 Jul 2011 07:15 am

Caroline Leaf meets John Canemaker

The following is from the book, Storytelling in Animation, The Art of the Animated Image Vol 2. This is an anthology that was edited by John Canemaker which was published in conjunction with the Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

A Conversation with Caroline Leaf

This transcript has been abridged from the “Tribute to Caroline Leaf” that took place on June 11,1988 during The Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

JOHN CANEMAKER: When Caroline Leaf was beginning work on her masterful short film THE STREET, she told an interviewer, “I wanted to tell stories with my films, and I used animal legends and myths. Now I am working more on dramatic representation: dialogue, character and human problems. Perhaps dramatic expression is not ultimately the best form for animation, but still, I do not try to do what live-action can do better. The strongest influence on me is from literature rather than film. Kafka, Genet, lonesco, Beckett, have affected me most with the depths of their visions and world views and ways of breaking up time to tell a story.”

Caroline Leaf’s work is a wonderful synthesis of many of the storytelling techniques and animation methods discussed at this conference. She represents to me both the old and the new—the traditional and the experimental. Her use of direct, under the camera techniques and brilliant metamorphoses recall the pioneering works of James Stuart Blackton and Emile Cohl. Her perfect sense of timing and implementation of personality to individuate her characters echoes the balletic movements and emotional impact of the best of Disney. Within her films the imagery can be, at one moment, representational, and, in the transitions, non-objective abstraction. Caroline tells ancient folk tales as well as modern short stories. And she uses tools as primal as her hands to position paint on a smooth surface, or push sand grains into impressionistic symbols. She records her art with a modern invention, the movie camera, which allows her to bring inert designs and stories to life, a miracle never realized by artists until our century.

Caroline Leaf created her finest films at the National Film Board of Canada, a sympathetic but nonetheless corporate structure, in which she has managed to retain her individuality and personal signature. She is also a vital link in the list of women animators, designers and storytellers past and present who have made their way in a male-dominated field. From the simplest means she conjures a complex world of emotions, which is a talent found only in the work of the greatest artists. The transformation and alienation of a man turned into a loathsome cockroach; the variety of feelings triggered in family members by the imminent death of a loved one; the pathetic, ultimately self-destructive attempts of a lovesick owl to assimilate into a different culture; a small boy and assorted animals facing death in the form of an eerily omniscient wolf are some of the stories told with consummate skill in the films of Caroline Leaf. I’m so glad you’re here.

CAROLINE LEAF: I’m glad to be here.

CANEMAKER: I think that what’s extraordinary about seeing all your work together like this is to view your first film and to realize that it was all there—right at the very beginning. The good design, the sense of timing, and your whole bold approach to the medium is already there—your ideas about how to tell the story. That was your first film, wasn’t it?

LEAF: PETER AND THE WOLF (1969) is my first film. And I must say, I agree. I haven’t changed very much.

CANEMAKER: Grim Natwick always said that timing is the last thing an animator learns. It seems as if it was the first thing that you learned. Where did that come from? Were you trained in theatrics in any way?

LEAF: I’m not sure where it comes from. I think I make shapes and then try to keep them in balance. That’s my idea of how they move. I don’t know how to say where the timing comes from.

CANEMAKER: But you also know when to not make them move—you have a good sense about “holds.” When the cockroach was looking in the mirror, it went on and on, and you had the guts to keep it there without having it move at all.

LEAF: I’ve heard people talk about feeling the movement, and I know that I feel it. Sometimes I have to get up and act something out, or look in the mirror to see what it looks like when something happens. Working directly under the camera the way I do, there’s nothing between me and drawing the motion, and that helps with that. Intuitive expression of the movement, the timing. CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about story. In PETER AND THE WOLF, it’s very experimental. In many ways it is a first film because you get a feeling you’re trying to do a lot of different things. How did you approach the story in PETER AND THE WOLF? There’s just barely a theme of Prokofiev in the beginning —it’s all there, yet it isn’t.

LEAF: I’ve read a lot, and I’ve been most influenced by stories that I have some good gut feeling about. But then I like to go off and do my own thing with them. And on that film in particular—you’re right, I was trying to experiment; and the way I was working, I just had to divide things into segments. The ideas would evolve out of a little pile of sand and then go into wh’ite, and then a few days later I’d start a new sequence. So, it was pretty much the situation of wanting to use a story while not following it precisely.

CANEMAKER: And you use touches of personality, too: the little goose steps down but has a very particular way of doing it and it got a couple of laughs each time because it was so goose-like. Your characters have a lot of personality. Do you feel that personality guides story?

LEAF: Can they be equal?

CANEMAKER: Whatever you want! Anything you want, Caroline!

LEAF: I would say the story is important to me because it sets the limits and anything I do I don’t want to deviate from the feeling I want to generate from the story. The characters are the vehicles that express the stories, so they have to be right for each other. And I don’t indulge the characters, I don’t think, because I would get off track with my story, so I think I always sustain a line to keep the story moving along.

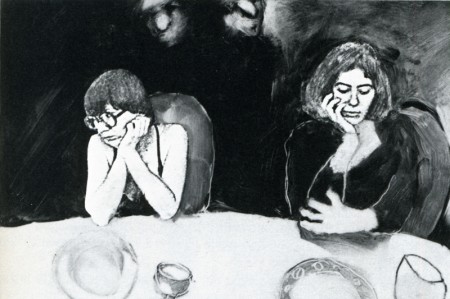

THE STREET (1976), adapted from Mordecai Richler’s story

CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about THE STREET (1976). How detailed was the original short story? Why did you approach it?

LEAF: I just liked the story, but there I had Mordecai Richler, a living person, a writer who lived not too far away from me, and I wanted to respect his writing. His story was maybe twenty pages, and at first I thought that to be respectful to the writer I should put everything onto film. And I found as I was working, the more I could pare away the words and just work with the imagery and be true to the feeling I was getting in the story, the better it worked on film. So there I was really trying to follow his story, but because film is a different medium, it came out in a different form.

CANEMAKER: Did you ever show it to him or did you confer with him during the making of it at all?

LEAF: No, he was strangely disinterested. He didn’t like the story too much, and didn’t care what I did with it, and never got in contact with me about it. I didn’t discuss it with him.

CANEMAKER: Did he ever see the finished film?

LEAF: I sent him a print and he never answered. I don’t know what he thinks of it.

A family beset in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)

CANEMAKER: What about Kafka? Was your approach to pare away and get the imagery first in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)?

LEAF: The Kafka story is so complicated and wonderful. There I took just the element of what I was thinking about most—how horrible it would be to have a body, or the external part of one’s self that’s seen by the world be different from what’s inside one’s self, and not be able to communicate that. Since I’m a storyteller, I just worked with that one aspect of Kafka, so it’s quite different from his original story.

CANEMAKER: You really get into your characters; the emotion is there, it’s really extraordinary, I think. It’s just great. (Audience applauds.) Caroline doesn’t like to be interviewed, but she’s consented to this, and I appreciate it. I’d like to talk about the animated projects you’re working on now. One of them is a scratch-on-film technique.

LEAF: I’m just in the midst of starting two projects, and because I’ve been involved with live-action filming for a few years, and writing for live-action, now I’ve got a story that has all the characteristics and psychology and emotion of a live-action film, but I’m doing the images scratching on film. It is quite a restricted and crude image that I can make, but I find it exciting to find what I can tell of the story in imagery and how much I’ll have to rely on words.

Autobiographical insight in INTERVIEW (1979), co-directed with Veronica Soul

And the other project is a test of a computer animation program. It’s a small project, a program called Pastel, that was developed by the Film Board. They wanted to see how an animator would work with it, and what modifications it still needs.

CANEMAKER: Exciting. So you haven’t abandoned animation.

LEAF: No. Not at all. I just have had a hard time sitting still and doing it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I noticed in INTERVIEW (1979) that you had all those little thumbnails to the left [of the work under the camera]. Is that how you work, really planning it out in little sketches like that?

LEAF: Yes, that would be my detailed storyboard as I go along. I don’t storyboard too closely; to have done all the fun work, and to animate it, there are no surprises left. But I also need to know where I’m going since I work under the camera. If I take a wrong turn I can’fgo back. So, as I come to each scene, I do some little sketches, particularly to know what the characters look like in different positions, so I don’t get lost.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Your soundtracks have a powerful impact on the film. How much do you get involved? Do you sound-mix, or do you direct the actors and the dialogue?

LEAF: I am very involved with my soundtracks, and I enjoy working on them very much. The soundtrack for THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974) was the first one I really conceived and executed. But when I’m working at the Film Board, I’m not the mixer, and I’m not the recorder, usually. There’s a crew of people that do that for me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You’re able to tell a story mostly through images, yet in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA and THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE you alter the language. Why did you make those choices?

LEAF: The Kafka story wasn’t in the public domain and I didn’t have the rights to the translation, so I made up a kind of gobbledy-gook language for that. And the Eskimo film was not a language you understood, either. They were speaking the Eskimo language.

CANEMAKER: THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE is exquisite. Sometimes in animation there are images you want to continue on and on and on. That scene of the birds flying, and the sound of wings getting as big and close as they are, and then they’re flapping for a while in front of you. I could watch it for a long time.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In that vein, I’d like to know how long you studied the animals to get their movements so perfect.

LEAF: I don’t study animals. I don’t go to the zoo. And in fact my movement isn’t very realistic. I think you can make it convincing. It fits the shapes, I think. I’ve never really looked to see how birds fly, and it’s kind of awkward in fact how they do, but it somehow works.

CANEMAKER: In several films you have a character who will take a step and then the legs would switch in some unnatural way—but somehow it works. In THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE I think there’s a section where that happens.

LEAF: I know it happens in THE STREET once — arms change . . .

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Why are you working in Canada? Economics?

LEAF: Yes, the Film Board is quite a special place. It’s allowed me to do the films that I’ve done, which I don’t think I could have done down here.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Because no one’s going to buy them? Or distribute them?

LEAF: It’s because of the problem with the distribution of short films. Ask any of the independent animators who’ve spoken here. Most of them are teaching, and it’s hard to have films seen. I found it is also hard at the Film Board. It’s difficult to have short films seen, and I’m not happy with the distribution, but I’m paid a salary there, and I’m quite free. Not totally free, because it’s a government film agency, and there are restrictions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What kind of restrictions?

LEAF: I find there’s a rather insidious way of thinking that grows on one working in a place like that. The most obvious thing is that it’s not possible to experiment; or it’s not easy to do an abstract film, because they’re always concerned about their market, which is an educational market. And besides that they’re very sensitive to not provoke any public outrage, or outcry, so they take a middle road. Nothing should be too controversial. I can read stories and know right away, this is something that could be done at the Film Board or not. One isn’t free to do exactly what one would like to do but one can mold it to be close enough to be satisfying.

Exquisite images of geese in flight in THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Does the Film Board expect to make their money back on films?

LEAF: No. The income they receive from the films goes back into production, but the Board receives government money each year. They have an annual amount given to them from Parliament. It’s voted each year.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Has it been growing?

LEAF: It’s been shrinking in recent years. So the place has shrunk a lot. Just last year they were voted an increase, which might just bring them equal with inflation for the first time in a few years. But everyone takes it as a vote of confidence.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Who owns the films you made while you were on salary?

LEAF: The Film Board owns them. I don’t have any rights to them at all.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do you think that your technique would be used in any major projects, for instance in a Disney feature?

LEAF: Well, I’ve seen my way of transforming used in eel animation. But actually the way I work, under the camera, I don’t think I can work as a team in that way. So it would be hard to make a long film using my technique, and get everyone working in a way that looks the same, This winter I did a commercial in New York, arid that was the first time I’d really found that my under the camera technique could work commercially. Because normally I would do some designs and then I would start, and I’d go to the end. And here I didn’t have any way to fit into the system of checks and balances that are used commercially. The client couldn’t see beforehand what I was going to do. But I evolved enough different systems of storyboarding that they felt reasonably secure, when I started animating, what they’d get when I’d

finished.

CANEMAKER: If it were possible to direct other people in your technique, would you be interested in doing a feature?

LEAF: No, I wouldn’t. I can’t imagine directing other people, and also I have a lot of fun when my fingers are doing it and I discover for myself little things. That’s what keeps me going. And I don’t know what it would be like, if it would be enjoyable to direct other people.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you ever used colored sand?

LEAF: I got tangled in knots one time trying to use colored sand. When you use colored sand—colored anything—you put a lot of time into keeping your colors separate, so they don’t all become like mud. And keeping colored sand grains separate was very difficult! I gave it up quickly.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you had students or apprentices pick up on your technique and pursue it in their own pictures?

LEAF: There are a few people that have worked in the same materials that I’ve worked in, but not as many as I’d like. And I haven’t had students. I haven’t taught.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Will you be working on a team for the computer animation?

LEAF: This is just a small project, and I’m alone with the guy that developed the program. We’re working together. He listens to my complaints and makes alterations. I’m amazed sometimes by what he’s done, but it’s not really a team.

CANEMAKER: I would like to thank Caroline Leaf for being here.

LEAF: Thank you for being here!

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Tytla 05 Jul 2011 11:28 pm

Tytla’s Hungry Wolf

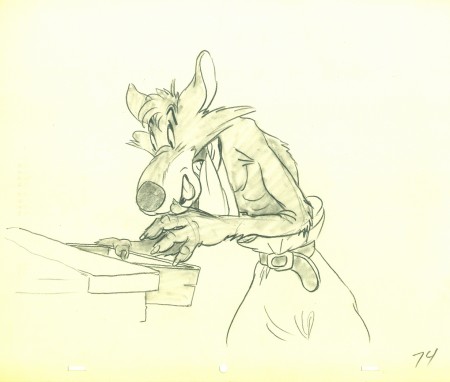

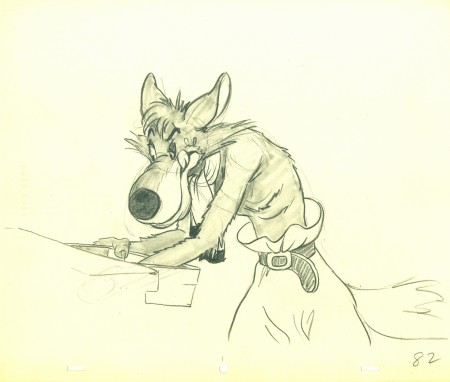

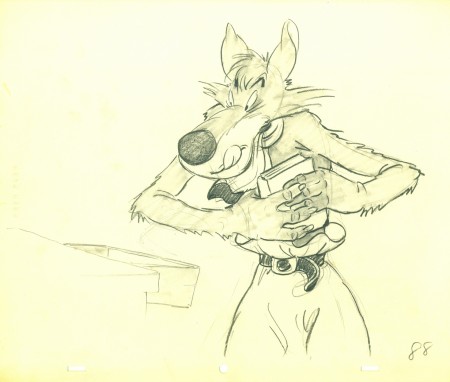

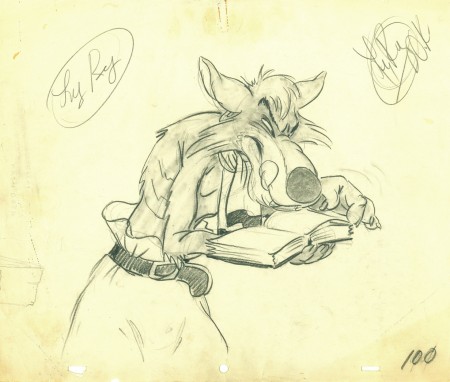

- Well, John Canemaker visited with a surprise. He brought a Bill Tytla scene. But this wasn’t Disney or Terry or Paramount. It was from a Hugh Harman film, The Hungry Wolf, made in 1940 at MGM. Not a very good film, the drawings are signed by Tytla, but they have no ladder indication for an Asst. to do the inbetweens. And most oddly, the wolves are shaded in by Tytla. Also take note of the table being animated into place. Are these animation drawings? Is it LO posing for someone else? And biggest of all, what is Tytla doing at MGM?

- Well, John Canemaker visited with a surprise. He brought a Bill Tytla scene. But this wasn’t Disney or Terry or Paramount. It was from a Hugh Harman film, The Hungry Wolf, made in 1940 at MGM. Not a very good film, the drawings are signed by Tytla, but they have no ladder indication for an Asst. to do the inbetweens. And most oddly, the wolves are shaded in by Tytla. Also take note of the table being animated into place. Are these animation drawings? Is it LO posing for someone else? And biggest of all, what is Tytla doing at MGM?

Since this would have been completed in early 1942, I can only assume that it was during the strike at Disney that Tytla did some work for Harman in mid 1941. Perhaps he came on as an animation director under Harman, who got credit for directing.

Here are all the drawings.

1

________________________

1

________________________.

The following is a QT of the entire scene with all the drawings included.

Since I didn’t have exposure sheets, I calculated everything on ones

(which seems to reflect the timing in the final film) and left however many

Many thanks to John Canemaker for the loan of the drawings. It was great just touching them.

Articles on Animation &Bill Peckmann 05 Jul 2011 06:48 am

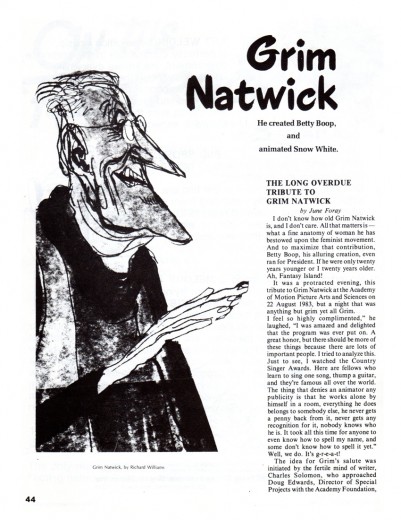

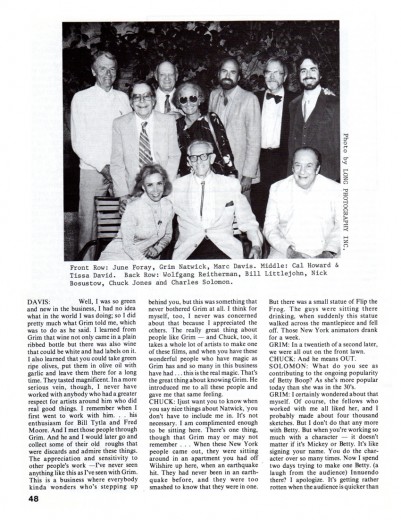

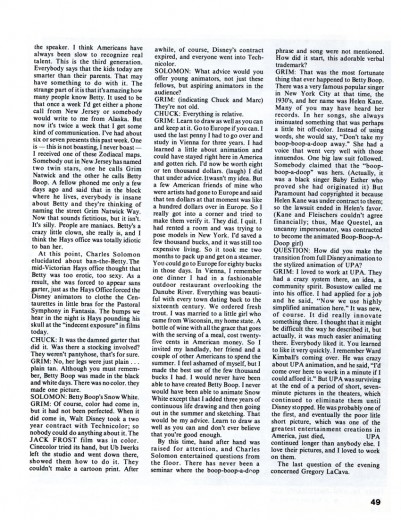

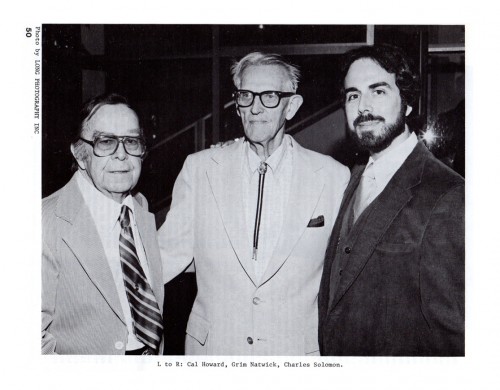

Grim by June

Photos &Steve Fisher 03 Jul 2011 07:32 am

Empire 4th

- I thought for July 4th, I’d forego any fireworks and put up some photos of pure Americana, at least my version of Americana. Steve Fisher has been photographing the Empire State Building forever. I’ve hesitated about putting up some of these beautiful photos over the years because I thought it might feel a bit repetitive to you. But this is one my favorite buildings (the Chrysler Building is my favorite), and it caught me off guard the other day. I was on 34th Street and a tourist asked me where the building was. We were about half a block away from it, so I just pointed. For some reason I got a twinge in my heart when I looked up at it. (As I said, I love that building.)

Immediately then and there I knew it was going to be the focus for today’s photo show. So, many thanks to Steve for digging out all these great photos.

1

1

7

7

21

21

Tonight TCM is screening the original KING KONG at 8pm.

I guess their programmer was thinking along the same lines as me.

Commentary 02 Jul 2011 07:53 am

More Odds & Ends

- A week or so ago Jeff Scher had a new film tha was posted on The NYTimes website. ‘You Might Remember This’ is a piece which focuses on Jeff’s son, Buster. Jeff writes:

While these films portray childhood, the perspective is parental. If Buster had made this film it would be all baseball, and the actual point of view, looking up at grownups twice his size, would surely feature more chins and nostrils. The angle might seem a small thing, but it can alter the feeling in subtle ways. Looking at children, our perspective is angled down and as they look up, we see eyes, those big ones, looking up like lasers. And, like every portrait, these films are double portraits, simultaneously reflecting the sensibility of who made them as well as who they picture.

While these films portray childhood, the perspective is parental. If Buster had made this film it would be all baseball, and the actual point of view, looking up at grownups twice his size, would surely feature more chins and nostrils. The angle might seem a small thing, but it can alter the feeling in subtle ways. Looking at children, our perspective is angled down and as they look up, we see eyes, those big ones, looking up like lasers. And, like every portrait, these films are double portraits, simultaneously reflecting the sensibility of who made them as well as who they picture. It’s a beautiful piece and well worth viewing. Like many of Jeff’s films, there’s a great score by Shay Lynch. (It’s worth visiting his website, too. He’s writing the score to Paul Fierlinger‘s next feature, Slocum.)

– Remember when Toy Story 3 came out, and the word from Pixar was that this was the last of the series? Now we learn that Tom Hanks has said the Toy Story 4 is in the works. (Will that come before or after Cars 3?)

– Remember when Toy Story 3 came out, and the word from Pixar was that this was the last of the series? Now we learn that Tom Hanks has said the Toy Story 4 is in the works. (Will that come before or after Cars 3?)

Hopefully, the future feature won’t be anything like the horrible little short that’s currently attached to Cars 2 in theaters. That short in combination with the companion feature, for an awfully tedious outing. I guess it’s too hard to pass up the billion dollars they made on the last Toy Story film; and who can blame them. It also received an Oscar and four nominations. Now they have a financial success with Cars 2, and you know the franchise won’t end there. (One wonders after the abysmal critical failure of this recent movie, will Lasseter continue writing and directing the upcoming film, himself?) Let’s hope that Oscar doesn’t fawn over Pixar with this terrible movie as they did with TS3.

Pixar is getting to smell like the Dreamworks of Shrek 4 fame. Anything for a buck – or is it a billion bucks for these things.

- One more thing I’ve been wondering about Cars 2. John Lasseter not only gets credit for directing (Brad Lewis gets credit as “co-Director”), but he also takes credit for the story along with Brad Lewis & Dan Fogelman. Ben Queen is credited for the screenplay.

- One more thing I’ve been wondering about Cars 2. John Lasseter not only gets credit for directing (Brad Lewis gets credit as “co-Director”), but he also takes credit for the story along with Brad Lewis & Dan Fogelman. Ben Queen is credited for the screenplay.

Now where does the storyboard fall into this schema? How do they work it? Do they write the “Story” first, then do a board changing things and then they write a screenplay from the board? Do they develop the story by doing a storyboard and then the script writer comes in to put down the dialogue? I’m curious as to how Pixar works. How does John Lasseter run Pixar, run Disney and then sit with board artists to construct a convoluted script like Cars 2? I honestly do not know. It sounds like a lot of hard work!

- Bill Benzon has an interesting piece on his blog New Savannah. In it he shows the connection between the 1945 Warner Brother’s cartoon, Book Revue, and the more recent feature-length film, The Secret of Kells (2009).

A site I hadn’t added to my Blog Roll until recently is Alltop. This lists the last five posts of a number of animation and drawing sites. It’s handy to see a large group of sites in a quick viewing to see if there’s anything you’ve missed. I also like seeing my site there on a regular basis.

- Grayson Ponti has a blog that is built around the 50 Most Influential Animators in Disney History. There’s a large number of people and their histories to wade through for Mr. Ponti, and it makes for a different kind of blog.

- Grayson Ponti has a blog that is built around the 50 Most Influential Animators in Disney History. There’s a large number of people and their histories to wade through for Mr. Ponti, and it makes for a different kind of blog.

I like that he not only looks at animators of the past but those of the present, as well. I don’t know many from the present and I should, so reading this blog acts like a wonderful crib sheet for me.

However, I wonder if these are the “most influential animators in Disney history” or just the lesser known. Although Mr. Ponti says that he, admittedly, has a hard time just selecting 50, I assume he’s gone over his quota. In a recent post, he does call Hugh Fraser, Don Lusk, Hicks Lokey and others “Honorable Mentions”.

Regardless, this is a fascinating blog and you should check it out. There’s plenty o’ reading here.

Note: The TAG Blog wrote about this last week. Mr. Ponti contacted me a week ago, but the link he sent me didn’t work, and it’s taken me ’til now to be able to get there.

I’m glad I did.