Monthly ArchiveApril 2010

Articles on Animation 10 Apr 2010 07:48 am

Animation in the USSR

The following is an article ripped from the pages of ANIMAFILM #1, 1979. This is definitely dated since the walls fell, the Recession hit and none of these companies exist anymore. However, it’s always good to cover a snapshot of history.

Animated film is a welcome guest everywhere. It fills people with joy and expectations. It is a cathartic and rejuvenating agent. Its magic holds people of all ages spellbound. The Home Committee for the Art of Animation, meeting in a plenary session in Kishinev, has deliberated upon Soviet animated film-making as an international art. Prominent Soviet artists, who have laid down the foundations for domestic animated film production, animators of international repute as well as young newcomers to the art, have thoroughly and seriously discussed the further possibilities for developing animated film.

Animated film is a welcome guest everywhere. It fills people with joy and expectations. It is a cathartic and rejuvenating agent. Its magic holds people of all ages spellbound. The Home Committee for the Art of Animation, meeting in a plenary session in Kishinev, has deliberated upon Soviet animated film-making as an international art. Prominent Soviet artists, who have laid down the foundations for domestic animated film production, animators of international repute as well as young newcomers to the art, have thoroughly and seriously discussed the further possibilities for developing animated film.

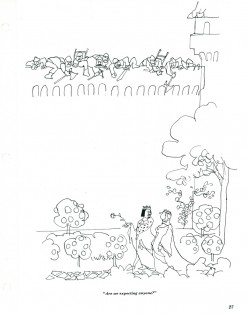

Gaydar’s little boy an Rudyard Kipling’s Mowgli, Charles Perrault’s

Cinderella and Little Red Riding

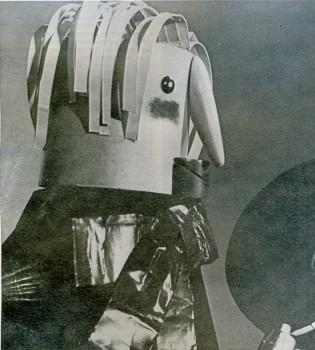

The Sauna, by Sergei Jutkievich, Anatoli Karanovich ____Hood, Alexei Tolstoy’s Buratino,

_______________________________________________and Ilya Muromets – the protagonist of the “hillins” (fables). Pushkin’s Duke Gwidon and the czar’s daughter-turned-swan by magic, Yershov’s Hunchbacked Pony, or Samuel Marshak’s and Korney Chukovsky’s enchanted animals – are the dearest friends from our childhood days. Animator’s hands and imagination have breathed new life into literary characters, making them available to young audience even before they can write and read. Actually, such encounters are for young viewers their first ineffaceable lesson in beauty, as well as a school of character because the stories deal with friendship, valiancc, goodness and justice. This is what the tremendous, inimitable value of animated film consists in. “Animated films cannot be compared to anything else”, said the great Soviet animator. F. Khitruk. at the Kishinev session.

Two-thirds of the animated film production in the Soviet is addressed to children. But adults value animated films equally highly. Its form makes this branch of art an ideal go-between linking adults and children. It is characterized by a variety of subjects, and a richness of styles, genres and ideas. The animated film industry is now developing in every Soviet republic.

Film, film, film, by Fedor Khitruk

The production of twenty-two republican film studios was reviewed in Kishinev. The Chairman of the Home Committee for Animation, B. Stepantsev, who holds the title of the Merited Artist of the Russian Socialist Soviet Republic, pointed to the very important fact that young film makers in Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Ukraine and Estonia have become widely known for their courageous study of current customs, morals and philosophical problems. This group of artists derives inspiration from native folklore and everyday events. Another notable group is the animators from Moldavia who are busy searching for unconventional forms of artistic expression.

The Kishinev session has shown thai the Soviet art of animation is expanding vigorously. (ATEM)

The distribution of short animated films, as other films not quite fitting the established standards of distribution, encounters problems. However, over the past 10 years the Soviet’s movie industry and distribution workers, cooperating closely with civic organizations and animated films popular both with children and adults.

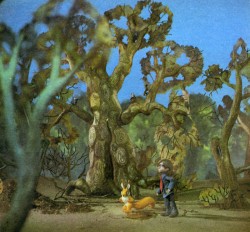

(Left) Farewell, Green Forest, by Michai! Kamenetski

(Right) One While Horse, by Vladimir Danilovich

The Soviet animated film studios annually turn out about 80 short films for children of different ages, not counting the films commissioned by various organizations, and didactic and advertising films. Every year the Soviet distribution network channels to viewers about 60 new animated films made in the USSR and about 20 such films made in socialist countries. On top of this the movie theatres have at their disposal about 500 archival films. Altogether, they avail themselves of a repertory of over 600 animated films, and that number is on a steady rise. Between 600 and 1000 copies of every film are made, some of them being reproduced on 16-mm tape for screening in schools and by travelling movie theatres.

.

There are various forms of film distribution, the most popular of them being feature-length package programmes. Sometimes such programmes exceed the standard length when a feature film is preceded by several, rather than one, short animated films. All in all, the package programmes are categorized into those addressed to children and (hose addressed to adults. Children’s programmes are mostly shown in special children’s cinemas (of which there are 300 at present) and during morning film sessions in standard cinemas on Sundays and holidays.

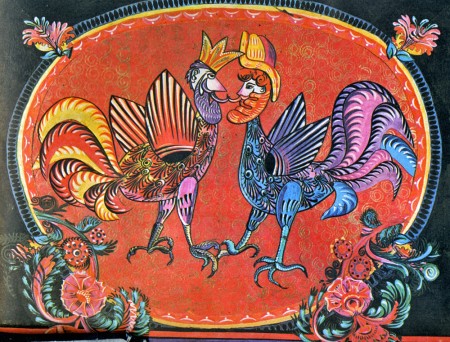

Gilt on Their Foreheads, by Nikolai Sercbrakov

Animated films tor adults chiefly accompany evening feature length film sessions or are shown in special short-films-only cinemas, of which there are over 200.

There also are four cinemas in Moscow which are exclusively used lo show animated films. Their combined capacity is 1.200 seats.

The methods of popularizing animated films are multifarious. For example, there are animated-film lovers’ societies attached to movie theatres attended by both adults and children.

The societies organize film shows to which they invite both domestic and foreign film animators and directors. Soviet audiences have already met with such animated film celebrities as Todor Dinov, Popescu-Gopo, Paul Grimault, Nedelko Dragic, Otto Koky, Stefan Janik and many others. Regular displays of works by the animators from the “Soyuzmultfilm” studio, and of children’s drawings, are held in cinema foyers. Every year animated film theatres have a turnout of 1,500 000 viewers.

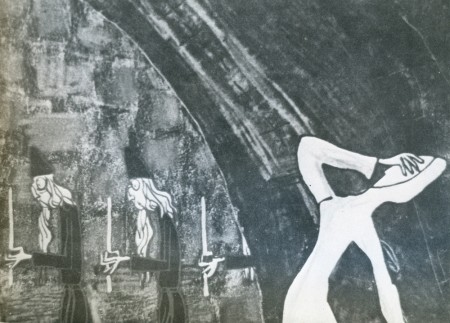

The Spear, by Rein Raamat

Soviet film-makers lake an active part in popularizing the animated film art. The most effective means they employ are the folk festivals organized in the individual republics, regions and districts with the help of the USSR Film-makers’ Association and film distributors. The festivals provide abroad forum for presenting the top achievements of Soviet animated film in cities, towns, and villages. The events are widely advertised and covered by the local press, radio and television networks. Special documentaries on the films shown, stories about the film-makers and interviews with the participants are regular items attendant on the festivals. The “Soyuzmultfilm” studio has already organized folk festivals in Western and Eastern Siberia, in the Caucasus and northern regions, the Far East and Central Asia. Artists from the “Kievnautchnyifilm” (educational film studio), which has an animation branch, take part in the festivals held in Ukraine. Also film-makers from Estonia keep in close touch with audiences. The folk festival in Moldavia marking the 40th anniversary of “Soyuzmultfilm” was a resounding success. Over 120 meetings between animators and audiences took place in the republic’s capital, Kishinev. Undeniably, the folk festivals stir popular interest in animated-film production and enlarge the scope of its influence.

The publishing house of the V/O “Soyuzingormkino” enterprise regularly brings out advertising and informative material on animated films meant for local film distrihutors and advertising and information centres.

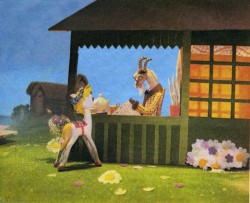

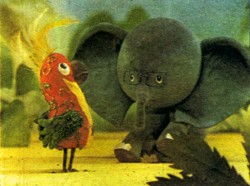

(Left) Where Is Baby Elephant Going, by Ivan Ufimccv

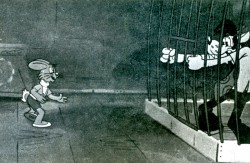

(right) Wait a Bit, by Vyacheslav Kotenochkin

Animated films are regular fixtures in central and regional television broadcasts. Every month the television networks in the Ukaraine and Georgia sponsor special broadcasts entitled the “Animated Films Panorama” and introduced hy the well-known animated film directors, Yevgeny Sivokon and Vachtag Bahtadze.

N. Venzher

This article gives me the opportunity of repeating a short anecdote on this blog.

It was 1977, and I was working at Raggedy Ann & Andy for Richard Williams. I was the head of Assistant Animators and Inbetweeners. A friend of mine who worked for an agency that supervised tours of Russian artists around the US, gave me a phone call. He was in NY with a pair of Russian animators who couldn’t speak a word of English, and he promised them that he’d try to get them into a NY animation studio. Could I do this on a Saturday?

I asked Richard Williams, and he said ABSOLUTELY NOT! (He was so violently against it, I could almost imagine that he’d had a bad experience in the past.) I called Faith Hubley (John was in England at the time working on Watership Down.) She and the studio were unavailable. The best I could do was to contact Howard Beckerman – in the same building as Raggedy Ann.

Howard had a one-man studio in NY, and had two small rooms and a couple of cubicles with lots of cel paint bottles coloring the space.

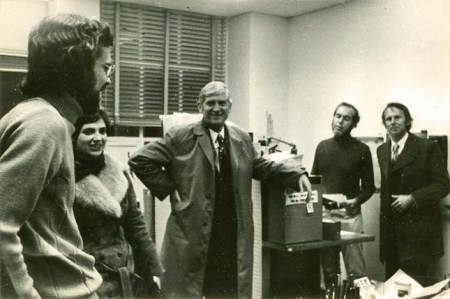

The two animators, who I met for the first time, were Rein Raamat and Vyacheslav Kotenochkin. I spoke poor to little Russian, with my friend, Richard Mayer, interpreting most of the conversation. We had a nice talk in their hotel room, went for a light breakfast and visited Howard, who was incredibly gracious and kind.

(L to R) Richard Mayer, Maxine Fisher, Vyacheslav Kotenochkin,

Howard Beckerman and Rein Raamat

Afterward, I offered to take them wherever they wanted to go in the City. I had my car.

Vyacheslav Kotenochkin wanted to go to “Yablokov Street”. I didn’t need a translator to figure out that that meant “Apple” street. I did need help to realize that he meant “Orchard” Street. “Yablokov” was the name of a storeowner on the street. I took them down to lower Manhattan to go shopping at these turn-of-the century type shops. Kotenochkin bought a dozen pair of jeans for his friends and a bunch of other things including a multi-colored clown-like wig. Rein Raamat just enjoyed watching.

When we were back midtown, Vyacheslav Kotenochkin left us for his hotel, and Rein Raamat wanted to see a Modigliani painting in the Museum of Modern Art. That was his favorite artist, at the time, and he’d never seen one in person. This part was easy. I was a member and got him in for free. When we turned the corner and this great big nude by Modigliani appeared Raamat gasped. A tear came into his eye, and the day was sunk in my memory as a key one.

For years after that, Rein Raamat exchanged letters and books. I’d sent him a large book on Modigliani and he sent me a German book on Bosch. We were able to write to each other in Russian. He didn’t speak it well, at the time, neither did I. Two people writing and reading pigeon-Russian seemed appropriate as a way of communicating.

Unfortunately, we haven’t spoken, nor have we written in a number of years. Though we have infrequently met up at some film festivals. Life’s like that some times.

See this post, to view some photos of the day.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration &Rowland B. Wilson 09 Apr 2010 07:20 am

RBW – color Istanbul & more

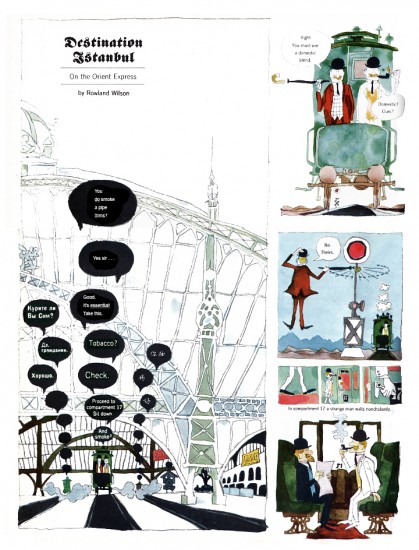

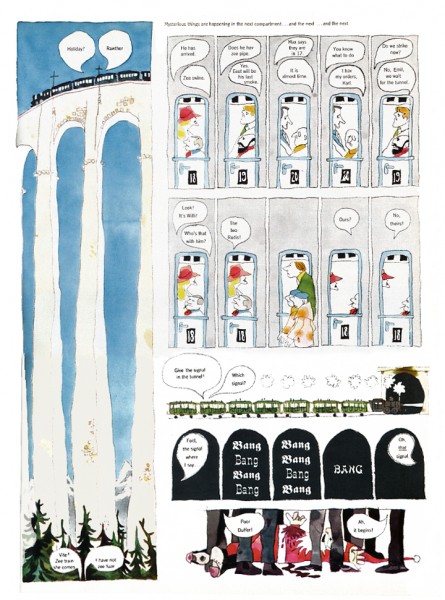

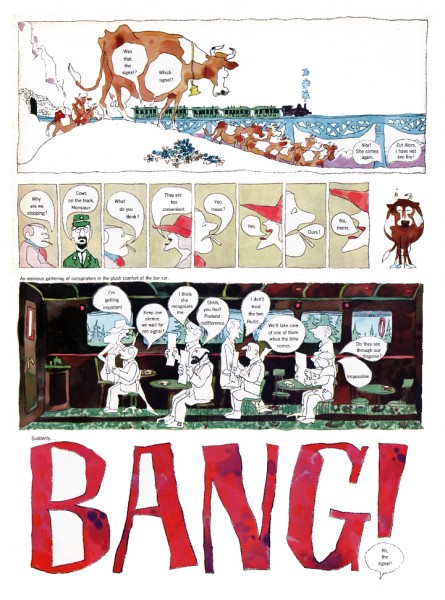

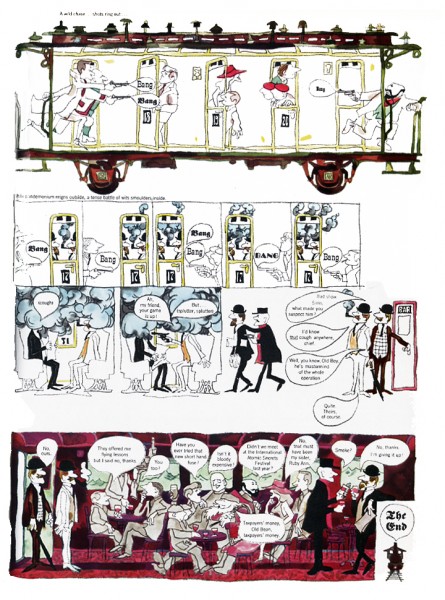

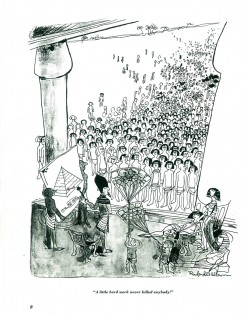

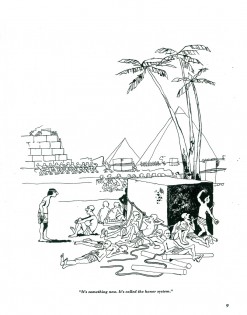

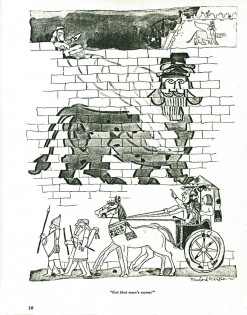

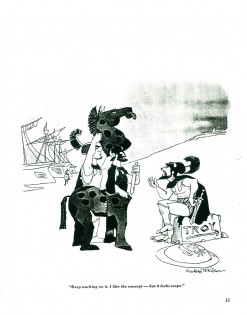

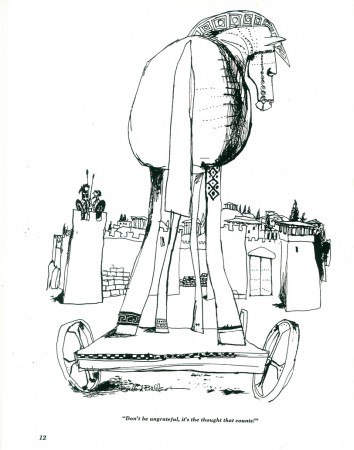

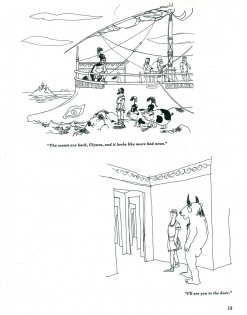

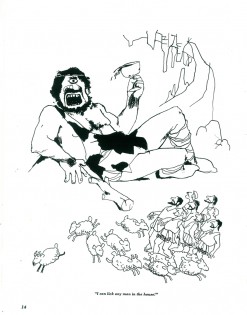

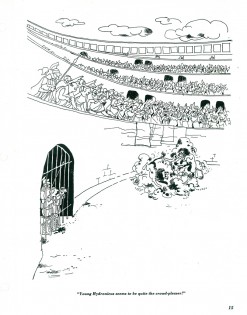

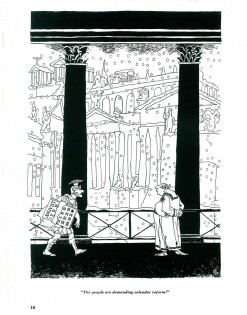

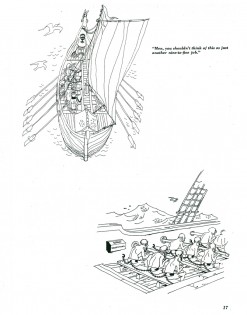

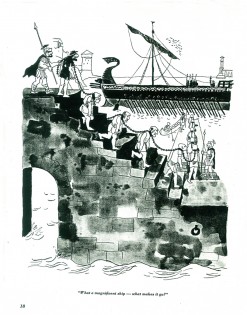

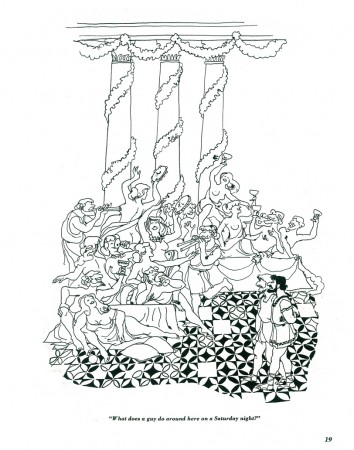

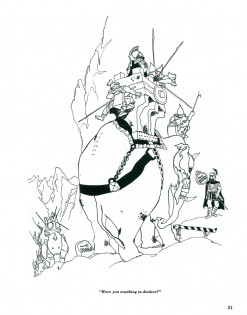

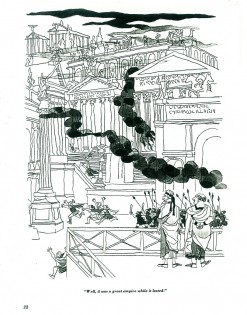

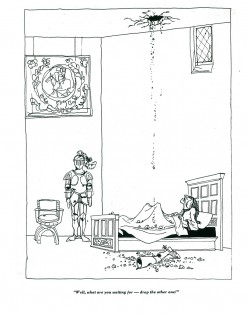

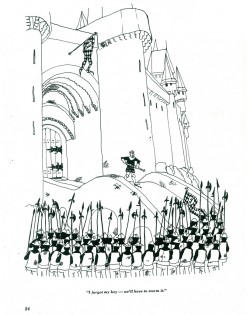

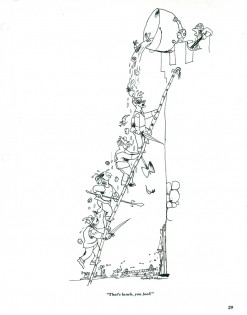

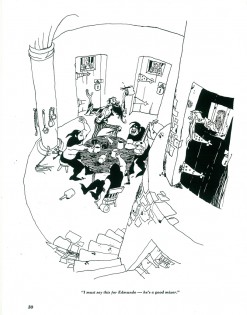

Rowland B. Wilson‘s Istanbul Express appears in his book The Whites of Their Eyes which was published by Dutton in 1962. However it’s in B&W and appears relatively small size. Hard to read. Denis Wheary, a first rate collector and authority on Rowland B. Wilson’s work, has kindly photographed the original Esquire publication in color and has sent these photos to me. Using some heavy photoshop work, I was able to clean up the photos to a very presentable shape. Here are the four pages.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

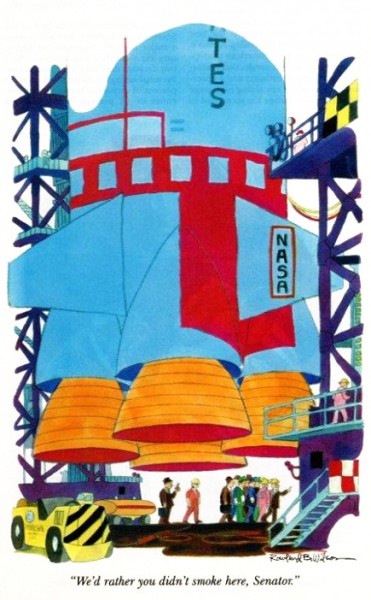

Here’s a color cartoon right out of Playboy courtesy of Bill Peckmann.

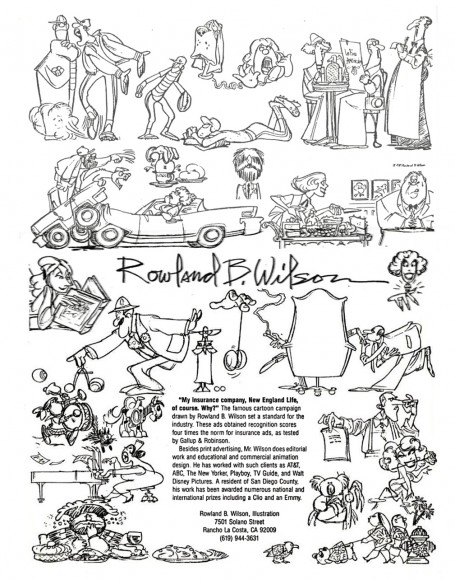

Also from Bill Peckmann’s outstanding collection of Rowland Wilson art is this flyer Rowland designed to promote himself.

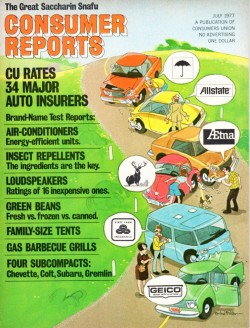

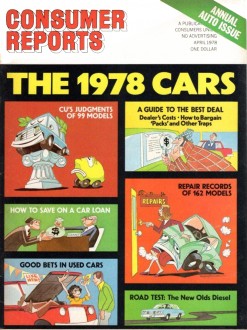

Here are a pair of Consumer Reports covers done by RBW.

I suggest you click to enlarge to check out all the detail.

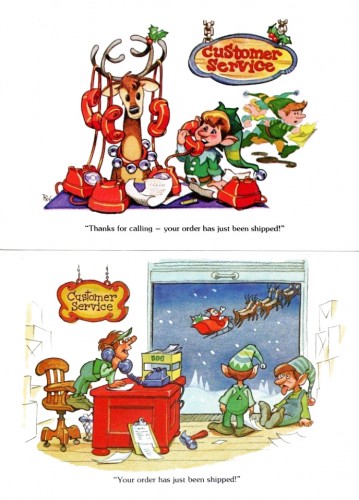

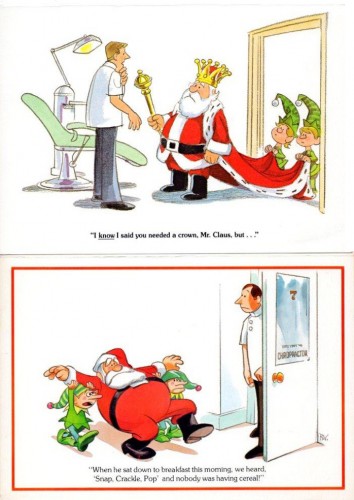

Here are a pair of Christmas cards RBW did

for some Customer Service center.

Bill Peckmann &Illustration 08 Apr 2010 07:27 am

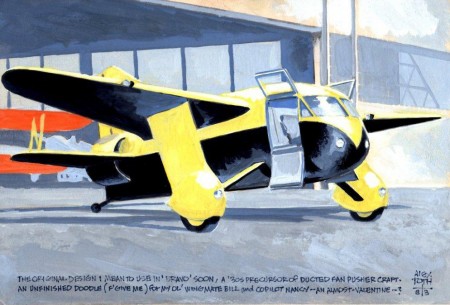

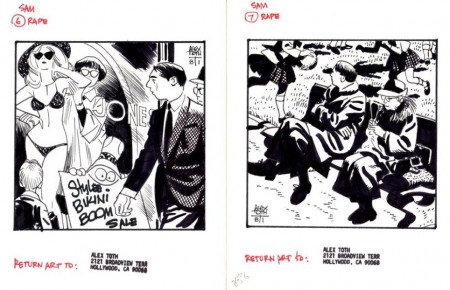

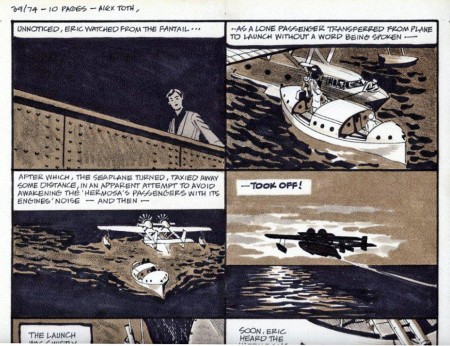

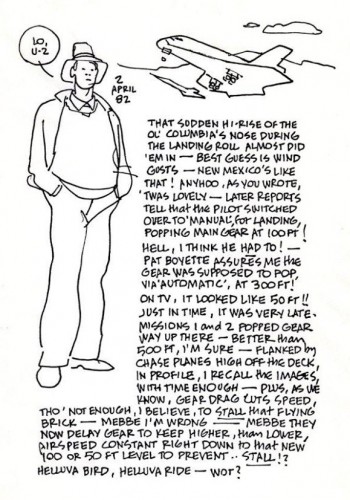

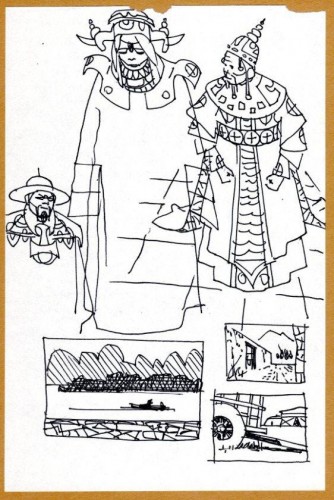

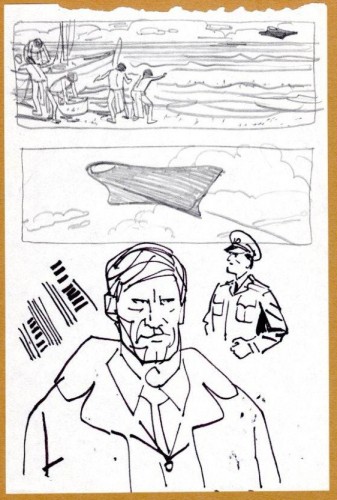

Alex Toth doodles

- Thanks to the inimitable Bill Peckmann, I have a few Alex Toth doodles which I’d like to share with you.

This is a color sketch done by someone who

obviously loves flying and loves drawing/painting it.

These are a pair of spot illustrations done for a newspaper.

Here’s a bit of animatic art done on vellum.

Here’s a bit of original Toth page art.

(this note from Bill Peckmann:) “This attachment has an Alex

doodle that I tried to turn into a ‘New Yorker’ cover . . .

. . . One rejection slip later, I still had the fun of Xeroxing and

painting it and now scanning it.”

I think the final piece, The New Yorker cover, is a piece of art in itself.

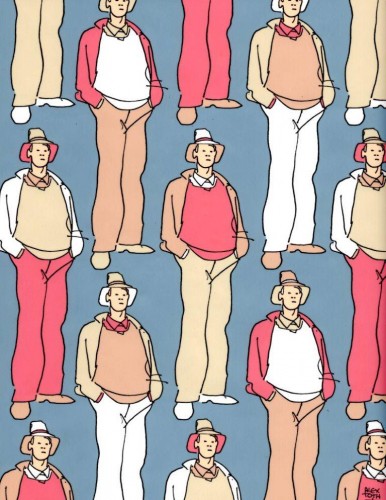

Bill Peckmann writes of this piece:

“This was made for fun, Alex’s ‘Underoos’ L.O. drawings were so well done (what else!) and posed, that I ganged up a few of them, Xeroxed ‘em and painted them. It’s a pan cel.”

Animation &Commentary 07 Apr 2010 10:03 am

Ace in the Hole

- Back in the day, when I was just a teenager, there was very little in the way of media, as there is today. If you were desperate to become an animator, there weren’t many directions to turn. You had what was on the four or five tv channels that existed and there was the library.

- Back in the day, when I was just a teenager, there was very little in the way of media, as there is today. If you were desperate to become an animator, there weren’t many directions to turn. You had what was on the four or five tv channels that existed and there was the library.

TV offered the Walt Disney show, which two out of four Wednesdays (later Sundays) each month, they’d touch on “Fantasyland”, and  you could watch some Disney cartoons – usually Donald and Chip & Dale, or there was the Woody Woodpecker show, during which Walter Lantz would talk for four or five minutes about some aspect of animation.

you could watch some Disney cartoons – usually Donald and Chip & Dale, or there was the Woody Woodpecker show, during which Walter Lantz would talk for four or five minutes about some aspect of animation.

For all those other hours of the day when you wanted animation you had to make do with what you could create for yourself.

At the age of 11, I took a part time job for a pharmacist delivering drugs to his clientele.

I lived off the tips that were offered, and I saved my money until I had enough to buy a used movie camera. The trek into downtown Manhattan was a big one for an eleven year old child, but I loved it. I went by myself to Peerless camera store near Grand Central Station. (It later merged with Willoughby to become Peerless-Willoughby; then it went back to just being Willoughby.)

I lived off the tips that were offered, and I saved my money until I had enough to buy a used movie camera. The trek into downtown Manhattan was a big one for an eleven year old child, but I loved it. I went by myself to Peerless camera store near Grand Central Station. (It later merged with Willoughby to become Peerless-Willoughby; then it went back to just being Willoughby.)

That store, I quickly learned had a large

section devoted to films for the 8mm crowd. Lots of Laurel and Hardy, Our Gang and Woody Woodpecker cartoons. Once I had the camera, I saved for a cheap projector and eventually bought some 8mm cartoons.

section devoted to films for the 8mm crowd. Lots of Laurel and Hardy, Our Gang and Woody Woodpecker cartoons. Once I had the camera, I saved for a cheap projector and eventually bought some 8mm cartoons.

Independence. Now, I didn’t have to wait to see them on TV, I could project them myself whenever I wanted. Even better, I jiggered the projector to maneuver the framing device which allowed me to see one frame of the film

at a time, so that I could advance the frames one at a time. I could study animation.

at a time, so that I could advance the frames one at a time. I could study animation.

I know, I know. I’m describing the stone ages. Today all you have to do is get the DVD (which is incredibly cheap compared to the cost of those old 8mm films) and watch it one frame at a time or any other way you want. And every film is available. If you don’t have it just join Netflix and rent it. Your library is always open and growing.

Yes, Peerless had an large 8mm film division, so you could buy the latest Castle film edition of some Woody Woodpecker cartoon, or you could find many of Ub Iwerks’ films. I had a collection of these. Ub Iwerks was my guy. Everything I’d read about him (in the few books available) got me excited about animation. Actually, Jack and the Beanstalk and Sinbad the Sailor were the first films I’d bought and watch endlessly over and over frame by frame.

Yes, Peerless had an large 8mm film division, so you could buy the latest Castle film edition of some Woody Woodpecker cartoon, or you could find many of Ub Iwerks’ films. I had a collection of these. Ub Iwerks was my guy. Everything I’d read about him (in the few books available) got me excited about animation. Actually, Jack and the Beanstalk and Sinbad the Sailor were the first films I’d bought and watch endlessly over and over frame by frame.

In short time, I knew every frame of Jack and the Beanstalk backwards and forwards. I didn’t realize that it was Grim Natwick who had animated (and directed the animation) on a good part of the film. Meeting Natwick years later, I think I surprised him by saying as much. He just moved on to another subject, appropriately enough.

In short time, I knew every frame of Jack and the Beanstalk backwards and forwards. I didn’t realize that it was Grim Natwick who had animated (and directed the animation) on a good part of the film. Meeting Natwick years later, I think I surprised him by saying as much. He just moved on to another subject, appropriately enough.

In some very real way, I learned animation from that film and several others that I

bought in those primative years of my career. Before I knew principles of drawing, I’d been able to figure out principles of animation. I’d had the Preston Blair book, and I had the Tips on Animation from the Disneyland Corner. I just measured what they said about basic rules and watched – frame by frame – how these rules were executed by the Iwerks’ animators. The rest was up to me to figure out, and I was able to do that.

bought in those primative years of my career. Before I knew principles of drawing, I’d been able to figure out principles of animation. I’d had the Preston Blair book, and I had the Tips on Animation from the Disneyland Corner. I just measured what they said about basic rules and watched – frame by frame – how these rules were executed by the Iwerks’ animators. The rest was up to me to figure out, and I was able to do that.

Eventually I bought a Woody Woodpecker cartoon. I was reluctant because so many of them were the very limited films done in the early 60′s – Ma and Pa Beary etc. It took a while to figure out that Ace in the Hole was a wartime movie and the animation would be a bit better. It was also the Woody that I liked – just a bit crazy. So I sprang for it and swallowed that film’s every frame for years.

Eventually I bought a Woody Woodpecker cartoon. I was reluctant because so many of them were the very limited films done in the early 60′s – Ma and Pa Beary etc. It took a while to figure out that Ace in the Hole was a wartime movie and the animation would be a bit better. It was also the Woody that I liked – just a bit crazy. So I sprang for it and swallowed that film’s every frame for years.

I’m not sure who George Dane is, (he seems to have spent years at Lantz before working years at H&B and Filmation) but I studied and analyzed his animation on this film closely and carefully.

I’m not sure who George Dane is, (he seems to have spent years at Lantz before working years at H&B and Filmation) but I studied and analyzed his animation on this film closely and carefully.

The work reminded me of some of the animation done for Columbia in the early 40′s. It had that same mushiness while at the same time not breaking any of the rules. Regardless, he knew what he was doing, and I had a lot to learn from him. And I did.

Things keep changing, media keeps growing. I’m glad I had to fight to get to see any of those old 8mm shorts back in the early years. When I bought my first vhs copy of a Disney feature, it took a while to grasp the fact that I could see every frame of it whenever I wanted. In bygone years, I could only see the rejects that TV didn’t want. I wanted to study Tytla and Thomas and Natwick and Kahl. Instead, I studied George Dane. And you know what, it was pretty damn OK. I

Things keep changing, media keeps growing. I’m glad I had to fight to get to see any of those old 8mm shorts back in the early years. When I bought my first vhs copy of a Disney feature, it took a while to grasp the fact that I could see every frame of it whenever I wanted. In bygone years, I could only see the rejects that TV didn’t want. I wanted to study Tytla and Thomas and Natwick and Kahl. Instead, I studied George Dane. And you know what, it was pretty damn OK. I  learned enough that I knew a lot when I started in the business. I just jumped in and was animating for John Hubley within days of getting that first job. (It helps that it was an open studio like Hubley’s where the individual artist could do anything, as long as he kept his head above water. In most studios there’s a rigidity that keeps you in your classified job.) In fact by then, I was more interested in Art Direction and Direction than I was in animation, but that’s another post.

learned enough that I knew a lot when I started in the business. I just jumped in and was animating for John Hubley within days of getting that first job. (It helps that it was an open studio like Hubley’s where the individual artist could do anything, as long as he kept his head above water. In most studios there’s a rigidity that keeps you in your classified job.) In fact by then, I was more interested in Art Direction and Direction than I was in animation, but that’s another post.

If you want to learn from the masters, just pop in a DVD and watch it frame-by-frame. If you don’t get a charge out of it, you might begin to wonder if you’re really in the right business. After all these years, I still get the thrill, and I imagine I always will – even from watching Ace in the Hole AGAIN.

Animation &Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &Puppet Animation 06 Apr 2010 06:15 am

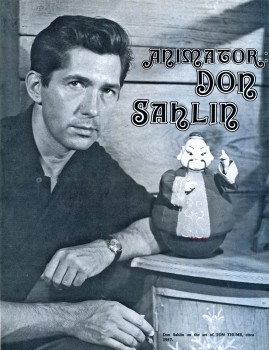

Don Sahlin

- After posting some stills from Ray Harryhausen’s Golden Voyage of Sinbad, I decided to look back and see if there were any other material I could post about 3D model animation.

I came upon this interview with Don Sahlin in Closeup Magazine, no. 2. published in 1976 by David Prestone.

(Bio)

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild.

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, Don Sahlin (say—lien) was introduced to the world of marionettes at age eleven, when he saw a production of HANS BRINKER AND THE SILVER SKATES by the New York Marionette Guild..

Joining the PUPPETEERS OF AMERICA organization, he was soon inundating many of that group’s members with letters of inquiry as to the correct method of constructing and performing marionette shows. This correspondence brought Don an offer from Rufus Rose (who, several years later, was to create all of the figures for the HOWDY DOODY televison show) to spend several weekends with Rose and his wife as an apprentice.

.

In 1946, Don started another apprenticeship of many years standing when he began working with Martin and August Stevens, who performed sophisticated marionette dramas of subjects like Macbeth, Joan of Arc, and Cleopatra.

.

A stint of Summer Stock in Rhode Island followed, when Don felt he would try his hand at the acting profession, but he soon became disenchanted with this form of theater work. In 1949, Don traveled to Hollywood, where he worked with puppeteerist Bob Baker, doing party shows for many of the movie stars there.

.

Don then returned home to perform a show of his own designing, SAINT GEORGE AND THE DRAGON, which played around the Connecticut area. Later jobs involved working with very large puppets accompanied by a symphonic orchestra, Chinese shadow plays, and, in 1950, a marionette version of the LAND OF OZ stories that Burr Tilstrom was preparing as a television pilot. Working for a year on this project, Don was then drafted into the army.

CLOSEUP: How did you first get involved with stop-motion animation?

.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup.

DON SAHLIN: When I got out of the Army in 1953, I had heard that Michael Myerberg was looking for puppeteers to work on HANSEL & GRET-EL. For some reason, he thought that puppeteers would make better animators than (stop-motion) animators! I was interviewed and got the job. I had to then go through a three-week training period with Myerberg in order to better acclimate myself with stop-motion. It was a very bizarre setup..

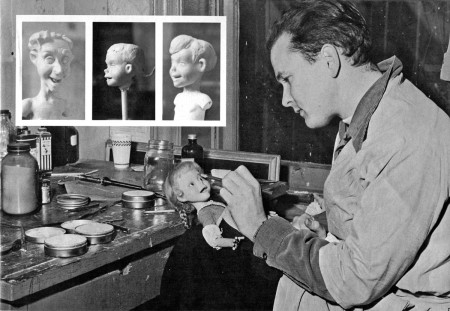

CU: Do you recall who sculpted the puppets?

.

DS: A man by the name of Jim Summers did the sculpturing. As I recall, they had a special machine shop where all the armatures were constructed. I’d give anything to own one of those armatures now. They were pieces of art.

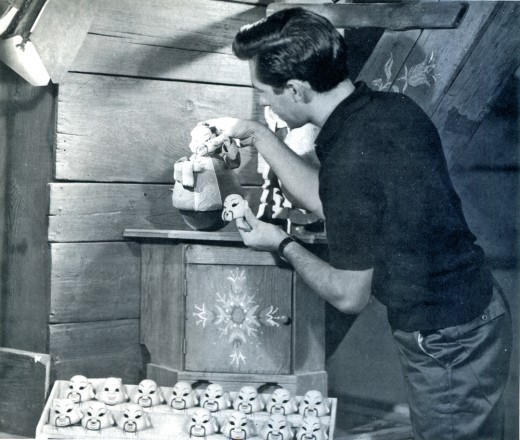

James Summers applies makeup to an almost finished Gretel.

Inset: Clay heads by Summers.

Below: Evil Witch Rosina Rubylips views herself

as portrayed in a preproduction sketch.

.

CU: Were they all ball-socket in construction?

DS: They were, but you’d press levers, which was really interesting. If you wanted to move the thigh, for instance, you’d press a little lever near the thigh area which would release it for a tiny movement. Removing pressure from the lever would freeze the puppet in position. As you may know, they were all held on the stage with electromagnets.

CU: Could you elaborate on how that was done? It’s interesting that Myerberg used that method of support as opposed to the tie-downs used by today’s animators. . .

DS: The base of the stage was all metal, and they had these strong electromagnets underneath. The puppets really clomped down on them. Of course, we’d have to break the electromagnetic field in order to move the legs to their next position. One night, as I remember, we were working on a very hard scene. Myerberg had a twenty-four-hour shift there, and the animation varied so greatly because people would come in and start animating where the day-shift had left off! We went out to dinner, and somehow, somebody had hooked the electromagnets into the main power source. Naturally, we killed all the lights as we went out. As we pulled the switch, we heard a series of plops. All the puppets had fallen over! We had to start the whole thing all over again! I quit twice on that film … I never got screen credit, because I quit before it ended.

CU: Here’s a quote from the book Puppet Animation in the Cinema: “The Kinemins used in HANSEL & GRETEL . . . were controlled by the use of electrical solenoids, and electromagnets in the feet. . . a system which is a closely-guarded trade secret…”

DS: (Laugh) That’s a lot of bunk, you know. The only thing “electronic” was the electromagnetic setup that held the puppets on the stage. Myerberg had a big panel upstairs where he’d use close-up heads that were wired to this big, blinking board. You’d turn knobs, but there was nothing electronic involved. There was simply a wire inside the mouth, and with a twist of a certain knob, the mouth would go “that way,” and so on. But it was all manual. Anything else that was said was a big put-on.

CU: A similar incident occurred with the publicity on Ray Harryhausen’s 7TH VOYAGE OF SIN-BAD, where the reporters of the media were quot-iny the producer on how the skeleton fight was “electronically” controlled . . .

DS: Nothing but press stuff, I would imagine. I’m glad you mentioned Harryhausen. God, I love his work. The one I saw recently again that I just adore was JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS. His work was absolutely superb. Classical mythology is such a wonderful area to explore. Why don’t they do more things like that?

CU: We’ve been asking ourselves the same question !

DS: Those skeletons were frightening! You know, I’ve learned to enjoy animation more now because I’ve been away from it for so long. But it’s a curious thing. Do you remember Trnka’s A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM? I saw it again and fell asleep through most of the whole thing! I was just so aware of how long it took to do each scene that it fatigued me … But it was a beautiful film.

CU: Getting back to HANSEL & GRETEL. Who actually did the camerawork on it?

DS: That was a very strange thing. Myerberg hired Martin Munkasci to photograph the animation. He was one of the great still photographers and had done a lot of things with Garbo and so on. Oddly enough, Myerberg felt that since stop-motion was nothing but a series of still frames, a capable still photographer would be more appropriate to do the camerawork. It was a very strange rationale on his part. Martin knew virtually nothing about motion pictures. Fortunately, a very fine Acme camera was used which was simple to operate, and he would just line up the shots and photograph. Anyhow, we went nuts, going up and down opening and closing those trapdoors all night long, sitting under that stage! And those sets were gigantic. Many of the backdrops were paintings, but a lot of it was also dimensional.

CU: We know that Myerberg isn’t with us anymore. What became of his organization after HANSEL & GRETEL?

Above: The beginnings of the KINEMINS . . .

incomplete sculptures of Hansel and his father .

Below: Several puppet figures and a set (which predate all work

on HANSEL AND GRETEL) from ALADDIN AND THE WONDERFUL LAMP.

All sets and puppets for this project were put aside

once work began on the Humperdink musical.

.

DS: Myerberg had all sorts of aspirations to do other things, but they never materialized. I think his sons own the film now.

CU: Where did you go from there?

DS: After I left Myerberg, I was in association with Kermit Love, who had also worked on the film. We were going to do a full-length motion picture Of Beatrix Potter’s TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER. It’s a charming story about a tailor and a Whole community of mice. We were going to animate all of the mice. We had the whole thing set up in London . . . Robert Donat was signed to play the lead role and Margaret Rutherford was also cast for the film. We began building the mice and we had some funding, although we hadn’t gotten to the point where we were able to build them all. Suddenly, we had a bad partnership and the whole project collapsed.

CU: Would the animated mice have been combined with live actors in the same scene?

DS: No, they would have been separate. I don’t really like it when they combine things, although Ray Harryhausen is a master at it. I wouldn’t want to do it in that way, but I respect what he does very much. Anyhow, I returned to the States when our TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER failed, and then got 3 call to go out and do work on TOM THUMB. That film, I think, was the most enjoyable thing I worked on during this period, because it was my first big job in Hollywood.

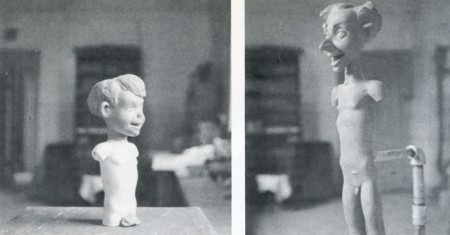

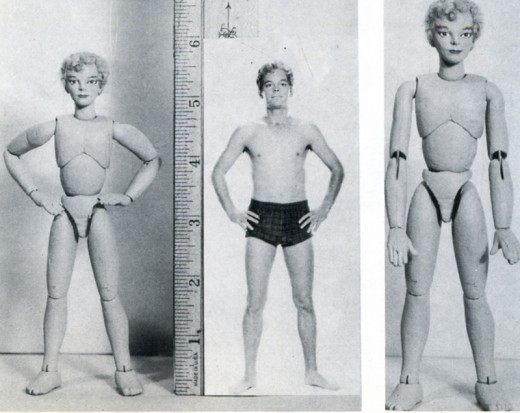

CU: How did you get involved with George Pal?

DS: At the time, 1 had been out in California working with a puppeteer friend of mine named Bob Baker. When TOM THUMB began, I was asked to build a little six-inch stop-motion marionette of Tom that they were going to use in the long shots. It was a funny thing. They said that he had to wear a fig leaf, so I carved this puppet with ball and socket joints, and he really looked naked. George was in England shooting in 1957, and decided that he wanted the puppet for a particular scene. But all my work was in vain, because the fig leaf that Tom wore covered almost his entire body. I had thought that the fig leaf would be in scale with his body, but that’s not the way it turned out. I think Wah Chang has the little Tom Thumb figure now, but I would love to own it. It was really an exquisite little puppet. It was all carved out of walnut, and I filled the legs with lead to make them heavy. It was never used in the closer shots, just distance stuff.

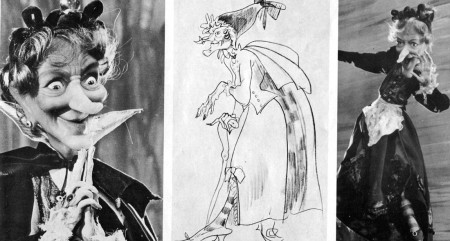

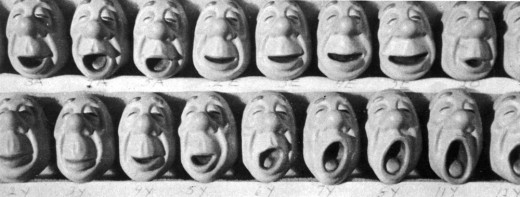

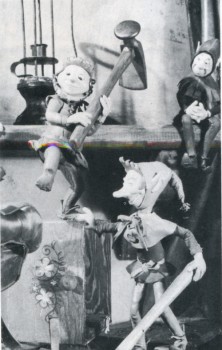

Two photos illustrating the replacement method of animation, utilized on TOM THUMB.

Instead of achieving changes of expression through manipulation of a stop-motion model’s

facial features, a series of heads are prodced, each head having a slightly different

expression on it. Changes are made by simply substituting one head for another.

Above: Don Sahlin placing a head on Con-fu-shun, and

Below: Numbered heads created for The Yawning Man animated by Gene Warren.

.

CU: How did you get to be a part of Project Unlimited?

DS: After I had carved the little stop-motion marionette, they started filming all of the animation sequences, but 1 had to go back to New York. Then Bob Baker called me from California and told me that they needed an animator. I talked to Wah Chang, I think it was, and he said, “Come on out and work for us!” 1 worked out at Project until about 1962. They wanted me to stay on, but Burr Tillstrom of Kukla, Fran and Ollie fame wanted me to come back to New York to work with him on a Broadway show. And it’s funny how fate is. I didn’t want to go; I really loved working at the studio, especially after THE TIME MACHINE. Anyhow, I did go to work for Burr on this small, cabaret-type show at the old Astor Hotel, but it soon folded. And like I say, 1 regretted leaving Hollywood, but I also met Jim Henson of the Muppets here in Mew York, and it led to probably my most successful period.

CU: Could you tell us just what you animated on TOM THUMB?

DS: I animated Con-fu-shun, a lot of the little guys that just popped up, and the Jack-in-the-Box. Gene Warren and I did all of the animation, just the two of us. Gene is a marvelous animator; he did the Yawning Man sequence. I spoke to Gene a little over a year ago, and I was so happy to find out that he does my favorite commercials—Chuck-wagon! To me, the most charming commercials ever done!

CU: What were some of the techniques used in animating Con-fu-shun?

DS: I remember Con-fu-shun was a very simple puppet. The armature was bolted to the stage and he just rocked. Occasionally, I think he got off for a couple of drop shots. The facial expressions were accomplished by replacing just the faces, which were made out of wax. We had a whole tray of all his faces. We’d just put on “E1″ or “E2,” or “Smile 1,” “Smile 2.” I know his eyes were not connected to the face; they were always independent. The faces just slipped on in perfect registration. I remember the little eye-pick I used for animating his eyes; it looked like a little hypodermic needle.

The TOM THUMB marionette created by Don Sahlin and used only in long shots.

CU: Did you have anything to do with constructing the large prop furniture, or giant hands and horse’s ears, that Russ Tamblyn was to interact with?

DS: No, that was all done at MGM, in England. Project Unlimited was a kind of neat little studio by itself, completely independent. Pal would do all of his stuff at MGM, but I wasn’t involved in the work done there, even on THE TIME MACHINE.

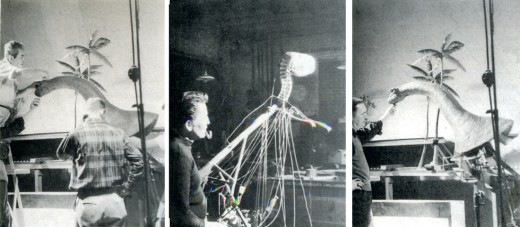

CU: You did some work on DINOSAURUS. Could you talk a bit about it? We know that,the models were built by Marcel Delgado, but little is known about who actually did what as far as the animation goes . . .

DS: I animated the Tyrannosaurus and the fight scenes that were involved with it. The rest of the animation was done by myself and Tom Holland; he got to do most of the Brontosaurus, the less ferocious of the creatures. I remember the night we finished the scene where the Brontosaurus died in the quicksand. The material used for quicksand was Fuller’s earth; I guess it’s used because it looks in scale. We had a kind of screw-jack that the puppet got on, and we kept pulling it down slowly in stop-motion, beneath the surface of the quicksand. When we finished the scene, we were exhausted. Then we asked ourselves, “Should we leave him in or take him out,” this great piece of sponge rubber? So we pulled him out again and we were hosing him off and cleaning him up. It was funny!

I also remember the night the big dinosaur fight took place. They were playing Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in the background and boy, it really inspired us to animate! We got through that fast, where they were tearing and ripping at each other.

CU: Is Tom Holland still animating in Hollywood?

DS: I don’t know what Tom is doing now. It’s interesting; Tom wasn’t really an animator. He was an actor, primarily, and he somehow got involved in animation. We did all of those scenes together. I recall another amusing incident on DINOSAURUS. Do you remember those close-up shots of the manually-operated dinosaurs that we intercut? We once spent a whole day boiling ochra and straining it to make it look like saliva was really dripping from their mouths. It was just hideous!

CU: DINOSAURUS is an interesting thing to look at as an animation film, but technically, it did seem to be somewhat under par in comparison with some of the others. . .

DS: It was a very cheap film. A lot of the rear projection work was just awful, especially the scene at the beginning when the guy came running out of the shack and the dinosaur came to life. Those shots were far from pleasing.

Project Unlimited technicians working on the large

manually-operated dinosaurs created for DINOSAURUS.

Left: Marcel Delgado applies the finishing touches to the Brontosaurus mockup.

Middle: Tom Holland and the Tyrannosaurs Rex “skeleton”.

CU: How big were the models in DINOSAURUS?

DS: Most of them were relatively small, except for the Brontosaurus, which was awfully big. You probably remember that we had a little doll of a boy riding on its back. I have a theory that large figures are hard to animate. Something happens, some strange phenomenon, which I can’t understand, takes place. I guess I’m not that kind of a perfect animator; I sort of do it loosely. I did TOM THUMB because that was all very contained. I got a lot out of the character as far as hand movements and so on. But the stuff that Jim Danforth did for BROTHERS GRIMM was just so superb that I would go insane doing that. I’m really into marionettes; I think that there’s a lot of potential in them for fantasy films in certain instances. I remember telling Gene Warren about some of those long shots where they were Trudging through the jungle in DINOSAURUS: “You know, I could do that better with marionettes.” I really think that one can augment the two.

CU: Project Unlimited also did some work on SPARTACUS…

DS: Yes, our little studio was always doing unusual props and effects for films, in between our animation jobs. Kirk Douglas was producing and starring in a monumental production of SPARTACUS, and Project Unlimited was called in to make about ‘ two or three hundred dead bodies, in various f scales, for some of the battle scenes. The largest * were about one-third life-size … We used molds to make them, and then we’d dress them in armor and sort of strew them all over the battlefields. I then i had to slash and “gore them up” with fake blood! We also made a bunch of horses out of polyure-thane foam. They weren’t very detailed, though-we just had to make sure they’d be recognizable from a distance, but none of them were shown in closeups.

CU: What did you do on THE TIME MACHINE?

DS: I worked on virtually all of the special effects.

There really wasn’t much animation, other than the decaying Morlock. That was done by Tom Holland. You know, I was in that film! I made my “screen debut.” Remember the guy in the window changing the clothes on the mannequin? That was me! I didn’t want the job because there was an actor there who worked with us, Dave Worrick. I asked them to give the job to Dave because I had no real desire to be in films. But they said, “No, we want you to do it.” So they got me a costume and animated me for the scenes.

CU: You mean you were actually pixillated as opposed to just speeding up the camera?

DS: Yes. I literally went in and they animated me per frame. The really neat thing about changing all of those costumes dealt with the fact that they were brought in from MGM. Somehow, in my subconscious mind, I recognized them. I remember saying to myself, “I’ll bet that’s a Lucille Ball dress.” Sure enough, it was, as their names are all sewn in them. But I loved the Morlock scenes. Some of the things I wish I had taken were a pair of Morlock feet and a Morlock head. They were great works of art; really spooky to look at! 1 animated the airplanes and dirigibles in the World War II scenes, but I never thought they were very realistic.

CU: In the earlier part of the film, there was a split-screen shot where boiling lava came oozing down the street. . .

DS: That was a great big fiasco, you know, because it didn’t really work. They had built these two bins full of colored oatmeal for the lava. One day, they decided to do a take. They covered all of the set with polyethylene. Now, they had prepared the oatmeal the night before, and nobody got up to look at it. Then they pulled the traps, with all these high-speed cameras going, and all the oatmeal had fermented and became watery. And the sight of all that! If I could have had a picture of the faces on those people! This foul-smelling, fermented mess came rushing down over all the cameras. I just went home. When they did the take again, they had put too much stuff together and it was too thick. I believe that’s how it appeared in the film. We were busy throwing burning cork and silvery material into the oatmeal, but it really didn’t work too well. It was fun, though.

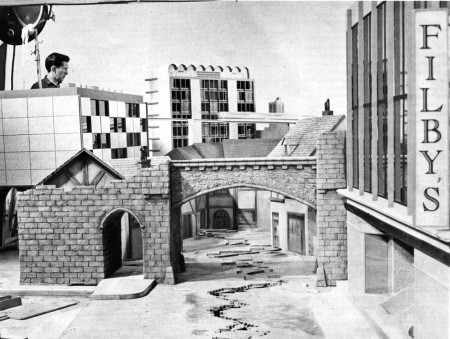

Don Sahlin on THE TIME MACHINE set.

Down this street will come the colored oatmeal “lava” flow.

CU: There was some inconsistency with the shot of you changing the mannequin. If the sun had been rising and setting at the speed depicted in the film, you shouldn’t have been able to see a man change a mannequin at all…

DS: Right. There are a lot of inconsistencies in that picture, but they’re very minor. It’s such a charming thing to watch. I never get tired of seeing it; it has such a haunting quality to it.

CU: Even the music and the actors seemed perfect.

DS: It did have a good score. Rod Taylor certainly seemed to be suited for the role. I had never been much of an Alan Young fan, but he played that triple role beautifully. And Yvette Mimieux was just out of high school at the time. The sound effects were great. I especially loved the off-camera sounds of the kettles underneath the ground.

CU: Did you work on the explosion scene towards the end?

DS: We had an incredible effect for that. We built a huge miniature set, about the size of a good-sized living room. It was all done on different levels of tables. We had legs underneath; and it was like a big puzzle. The legs were pulled at different times so the set would collapse. Then there would be explosions and flash-pots going off. It was really effective. There were many other scenes in THE TIME MACHINE that I worked on. There was the opening scene of the candles melting, and the ones of the flowers blooming. I remember we animated a snail; I also animated the Sphinx. You might recall the raising and lowering of those siren towers …

CU: Were they cardboard cutouts or was it a full miniature?

DS: It was dimensional. But there was very little animation involved in that. There was another scene, a blue-backing shot, where layers of lava were made to appear rising behind Rod Taylor in his Time Machine. That was all painted. They had a guy in another room, Bill Brace, an artist, and he was doing all those matte paintings where the trees were blooming and the apples were growing. And he painted the future scenes, too, where you saw the topography of the land changing, and the Eloi temple being built. The whole dome of that was a painting matted in, and the stairway leading up to it was part of MGM’s old QUO VADIS set.

DS: It was dimensional. But there was very little animation involved in that. There was another scene, a blue-backing shot, where layers of lava were made to appear rising behind Rod Taylor in his Time Machine. That was all painted. They had a guy in another room, Bill Brace, an artist, and he was doing all those matte paintings where the trees were blooming and the apples were growing. And he painted the future scenes, too, where you saw the topography of the land changing, and the Eloi temple being built. The whole dome of that was a painting matted in, and the stairway leading up to it was part of MGM’s old QUO VADIS set.

Do you know what I loved about working on TIME MACHINE? We literally did the sets ourselves. I loved doing the sets and dressing them. We were all very involved in the whole project instead of just one aspect of it. I remember working on that huge hole that Rod Taylor climbed into to get to the Morlock world. I loved getting down there, touching it up with a spray can and adding little details to it. I really feel proud to say that I worked on THE TIME MACHINE; I think it was a classic. I never received screen credit due to the politics of the organization, but it never bothered me. We were working on a very small budget. I think I remember Gene telling me that we did the effects for under $60,000, which was really a smal sum, yet it reaped an Academy Award. Have yot ever met George Pal?

CU: We’ve never had the pleasure.

DS: When you think about him, he was such an unusual producer when you realize the courage he had to have to do the kind of offbeat things he did.

CU: The last film you worked on for him was THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM. Could we talk about what you did on that one?

CU: The last film you worked on for him was THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM. Could we talk about what you did on that one?

DS: I did a lot of the animation, especially the scenes involving the elves. The opening scene of the elves took me a whole week to do. Dave Pal and George’s other son, Peter, worked with me. We got along famously. I had to leave before the picture was over, so Dave carried on from where I left off.

CU: Did you work with Jim Danforth on the film?

DS: Not directly. I was in one corner of the stage, and Jim was working in the other corner. It was so tedious because of the Cinerama camera. Each frame had to be photographed three times. You had to be careful not to make any mistakes. We couldn’t talk at all. Peter would work the camera and we made it a point never to talk to each other because it was so easy to make an error. I was animating five elves, and he had to work that complicated turret camera.

CU: Didn’t you have to brace some of the elves? Some of them had to leap off the stage. . .

DS: Yes. We had a lot of wire stuff on the film. The wires were very thin and they were coated with iodine. You really couldn’t see them. Each time we’d reposition the puppet, the wires would be in a different part of the frame. So they really cancelled themselves out.

CU: Did anything unusual happen on the animation set?

DS: I do remember one funny thing that happened on BROTHERS GRIMM. There was a scene where an elf walked across the set with a shoe. The peg holes, by the way, were covered with clay and painted to match the set each time the elf took another step. Anyway, one of my little mice from the aborted TAILOR OF GLOUCESTER project got into a frame while the elf was being animated. Just for one frame. It was a terrible thing, but Pal never saw it!

CU: Did you do anything outside of the elf sequences?

DS: Wah Chang set up all of the shots and lit them. While he was doing that, I loaded the camera, which to this day frightens me because I don’t consider myself that technically inclined. I also did all of the calibrations and animated the camera for trucking shots. All the fades and the simpler opti-cals were done in the camera.

CU: Did you actually plot out all of the animation before it was photographed?

DS: We had to on some of the things. When there are faces involved as there were in TOM THUMB, and you have to do all the vowels and so on, you have to plot them out beforehand. But I like to animate sort of “free;” I don’t like to be restricted too much. You mentioned Jim Danforth before. I believe I met him while I was doing TOM THUMB. He was very young at the time and was very wide-eyed at what was going on. He seemed so impressed with our setup. Then I saw his reel that he had done in his garage. He did incredible stuff, op-ticals and everything. He’s a genius; he really is an incredible animator. He’s so much better than I am because I haven’t the patience to do the detail that he does. I remember him animating the dragon in BROTHERS GRIMM. He did that whole thing, and he spent days with all sorts of pointers. He’s a perfectionist.

CU: Now that you’re no longer involved in stop-motion, could you tell us about your work with the Muppets?

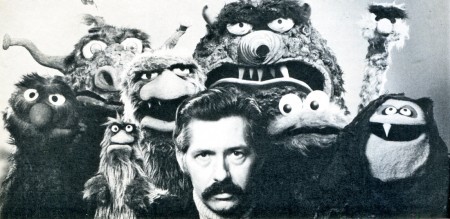

DS: I build and co-design Jim Henson’s puppets. He starts out with a little thumbnail sketch; I would say that he really creates the essence with his sketch. Then I start building it. Jim comes in and looks at it and we play with them to see how well they’ll work. But it’s really a joint effort, although I don’t do any of the puppeteering. I built many of the most famous of the Muppets. Kermit the frog, Bert and Ernie, the Cookie Monster, and most of the others.

CU: You did two “counting films” for Sesame Street. . . were these very recent?

DS: Not really. They were done around 1970, right here in our Muppets, Inc. offices. Jim Henson supervised the filming, but he gave me all the freedom in the world to do what I wanted. THE QUEEN OF SIX was filmed on a rug, to simulate grass, and the backgrounds were all painted cardboard. The Queen figure was about 13 inches tall and I wanted her to have a very baroque, dresden sort of look. Her hoop skirt was a big lampshade that I put brocade on. She had a beautiful Marie Antoinette wig that I made out of silver thread, and I used one of those plastic Easter eggs you can buy for her head.

DS: Not really. They were done around 1970, right here in our Muppets, Inc. offices. Jim Henson supervised the filming, but he gave me all the freedom in the world to do what I wanted. THE QUEEN OF SIX was filmed on a rug, to simulate grass, and the backgrounds were all painted cardboard. The Queen figure was about 13 inches tall and I wanted her to have a very baroque, dresden sort of look. Her hoop skirt was a big lampshade that I put brocade on. She had a beautiful Marie Antoinette wig that I made out of silver thread, and I used one of those plastic Easter eggs you can buy for her head.

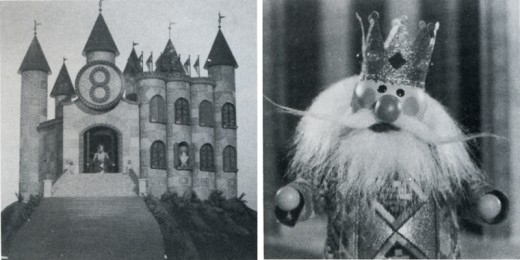

CU: I recall the other “counting film” you did, THE KING OF EIGHT, with the rhyme-speaking king, and his eight daughters opening and closing the windows of his castle. Both of these films were fairly short, weren’t they?

DS: Yes, none of those films done for Sesame Street are over a minute in length.

The King of Eights

CU: Are you satisfied with the work you’re doing now?

DS: Certainly. It’s very creative and enjoyable. I remember that when I was a kid, my sister wanted me to take regular college courses. I told her I wanted to take art courses. She would say, “What can you do with art? You’ll never make a living do ing puppets.” And it was only recently that we reminisced about that and, not trying to sound egotistical, I said to her: “Do you know that my puppets are all around the world?” Now that Sesame Street has been distributed in Europe, I have great satisfaction in knowing that my creations are

being seen and enjoyed internationally.

Don, as he appears today, with some of his more

“gruesome” creations for the Henson MUPPETS.

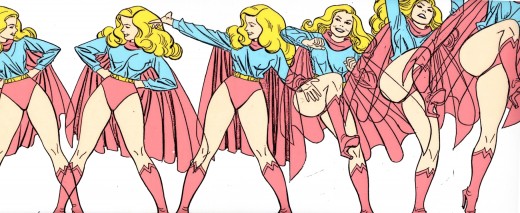

Animation &Disney 05 Apr 2010 07:27 am

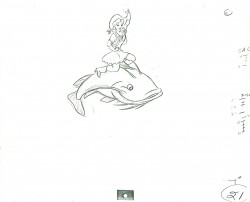

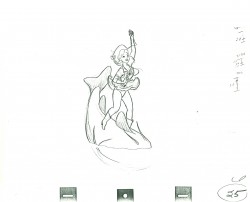

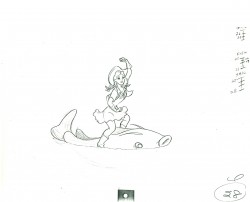

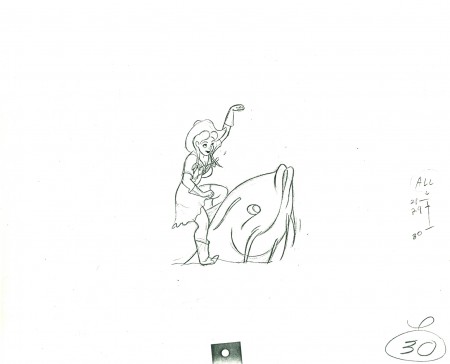

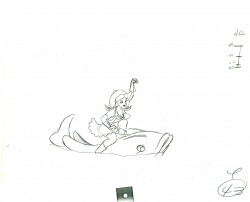

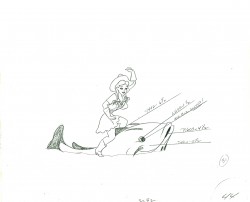

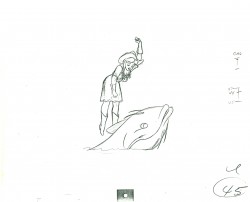

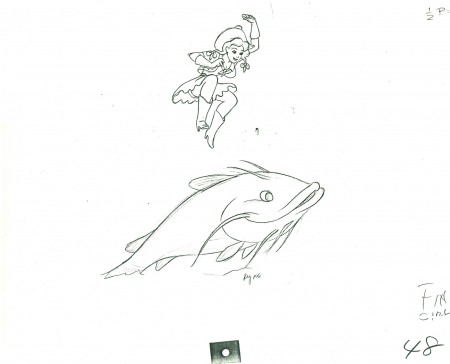

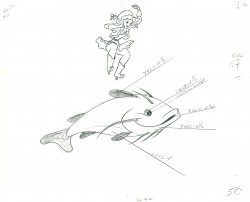

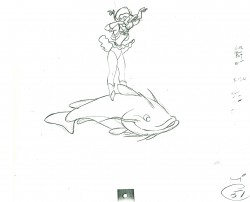

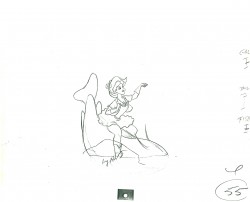

Slue Foot Sue – 1

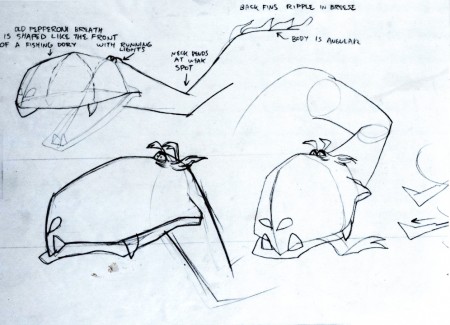

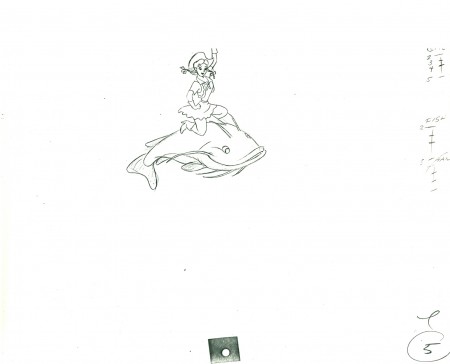

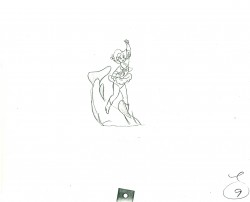

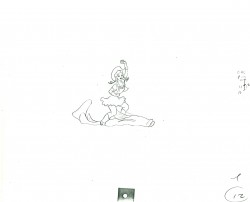

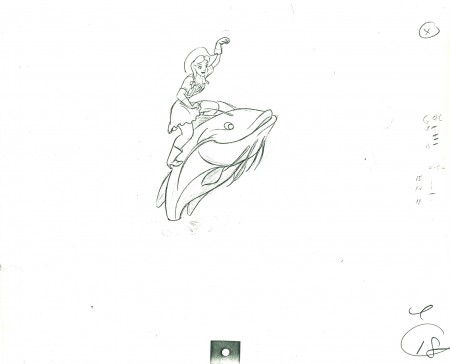

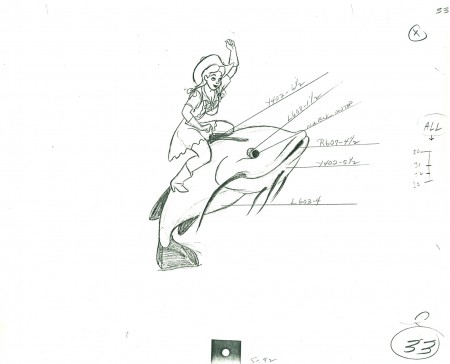

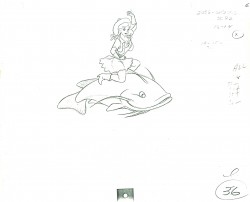

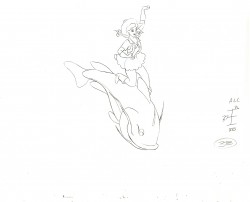

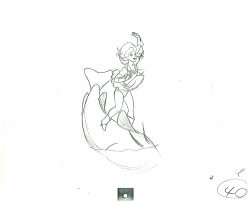

- Here’s Slue Foot Sue riding a fish in the Disney short Pecos Bill. The piece was animated by Milt Kahl and loaned to me by my friend, Lou Scarborough. I’ve had to split the drawings into two – Part 2 will be posted next week.

Three of the drawings in the entire piece were traced rather than xeroxed and these three won’t have to be pointed out.

1

1  2

2(Click any drawing to enlarge.)

The following QT represents all of the drawings from the scene,

not just those seen above. Each extreme was held for the

appropriate number of frames requested.

Right side to watch single frame.

Photos 04 Apr 2010 08:26 am

Easter Sunday photos

Animation &Puppet Animation 03 Apr 2010 07:53 am

Bill Benzon/Harryhausen

- Bill Benzon has been writing some particularly fine pieces for The Valve, and he just posted a lengthy and heady article called The Rings of Fantasia. When Bill notified me about the piece, I asked if he minded my reposting on my site, and we agreed to go ahead with that. However, after doing all the work of setting it up, I’ve decided it’d be wrong to do so. It’s better just to link to it so that The Valve, the original site that Bill regularly writes for, will get as much attention as it deserves for showcasing such a writer as Bill.

I suggest you check it out and read some of the many other pieces Bill’s written. He’s a great supporter of Nina Paley’s work, currently highlighting the web comic strip she’s doing, Mimi and Eunice. (It’s good to see Nina creating again after the long promotional wind-down of Sita Sings the Blues. By the way, Bill Benzon wrote a wonderful and positive piece for The Valve about that film, as well.)

So in the end, let me encourage you to go and read. There’s some great stuff by Bill Benzon at The Valve.

- Clash of the Titans opened yesterday to mediocre and negative reviews. Watching trailers for this film made me sad to see the work of Ray Harryhausen tramped on by the cg generation. There’s no possibility a computer driven model could carry the same weight that the magnificent creatures of Harryhausen brought to the orginal. His films were always annoying in that they had a bevy of bad acting and live-action direction all in the service of the brilliant effects. Harryhausen’s creatures were the real stars of his films whether Jason and the Argonauts, either of his two Sinbad movies or Clash of the Titans. Even watching the clips of the cg effects brought me down. Something about the original’s stop-motion jerkiness added a weight, a reality to the form. The computer effects have become so generic that to go from this film to even the Mummy movies becomes almost interchangeably tedious. There’s basically no difference and no reason to see the film.

Instead I did see a running of the original and several other Harryhausen films on TCM recently. The mix of greatness and the B-movie live-action was almost delightful. These films have become iconic, and they’re irreplaceable.

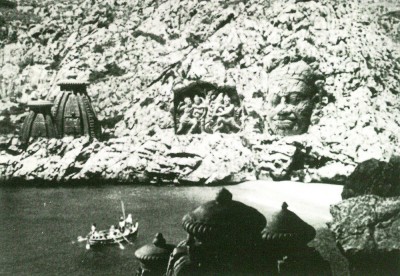

To honor Harryhausen, I want to post some production stills. I don’t have pictures from his Clash of the Titans, but I do have plenty on The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, the film just prior to that. So here are some of those images.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

2

2

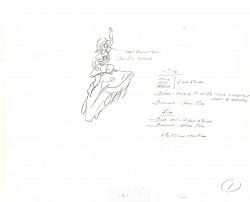

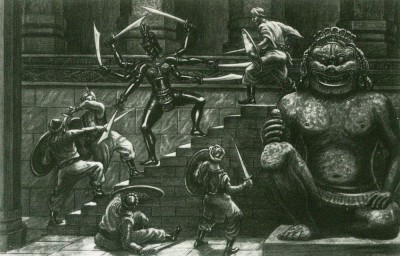

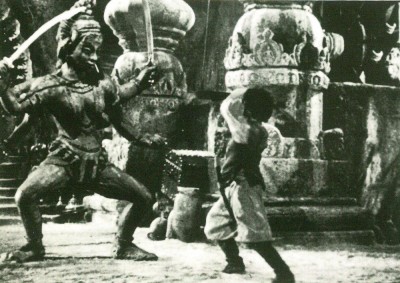

The original drawing of Sinbad and his men

fighting the golden Kali.

3

3

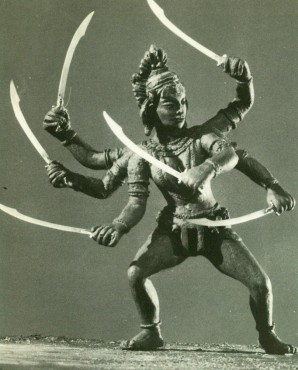

The golden Kali comes to life.

4

4

Very complicated staging of the sword fight had to be done

to keep the scene looking authentic.

6

6

An early Harryhausen preproduction drawing of Kali dancing.

7

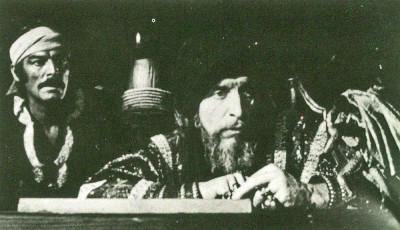

7

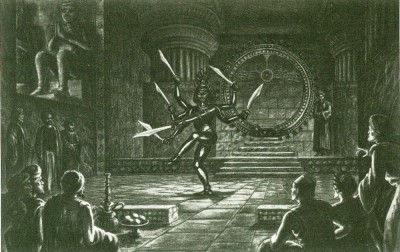

The magician beckons Kali to descend the stairs.

8

8

John Stoll designed and supervised the many sets for the film.

Fernando Gonzalez was the Art Director.

9

9

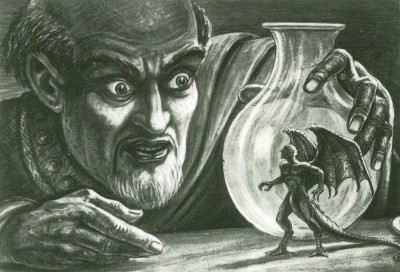

An early Harryhausen preproduction drawing of the Homonuclus.

10

10

Kaura and Achmed look on in wonder as

the Homonuclus comes to life.

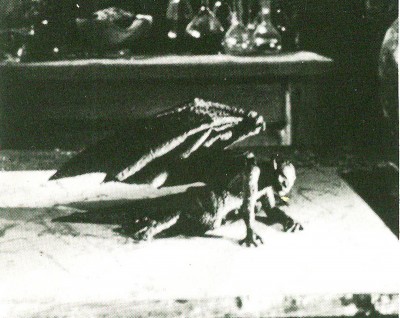

11

11

The Homonuclus first tries out its movement.

12

12

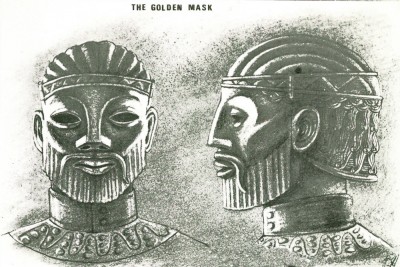

Designs for the Golden Mask worn by the Vizier whose face

has been disfigured by Koura the Magician.

14

14

Beach scenes of Majorca substituted for

the Ancient continent of Lamuria.

15

15

The construction in the beach wall and the ship were added later.

16

16

Haryhausen (R) and cinematographer, Ted Moore (L), on the set.

Bill Peckmann &Books &Illustration &Rowland B. Wilson 02 Apr 2010 08:21 am

Rowland Wilson’s Whites

- Last week, I’d posted some dragon models that Rowland B. Wilson did for animation company Phil Kimmelman & Ass. for ‘Utica Club Beer’. Well, it turns out Rowland liked the model enough that he kept this painting on the wall in his studio at home. The color image was sent to Bill Peckmann, who shares it with us, by Suzanne Wilson, Rowland’s wife.

This is the model posted last week.

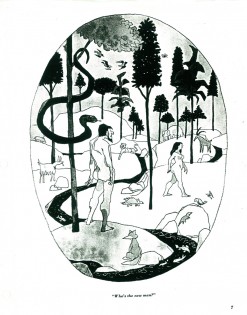

All that I can follow that up with are more Rowland B. Wilson cartoons. Bill Peckmann had sent me a xerox copy of the book The Whites of Their Eyes, a collection of RBW cartoons printed in 1962 by Dutton. The copies are all B&W though it’s obvious some of them were printed in color. Many thanks to Bill for another great post featuring one of my favorite artists.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge and read.)

Hubley &repeated posts &Tissa David 01 Apr 2010 09:37 am

Letterman Flips the Ball – recap

This piece was originally posted on April 1st, 2008:

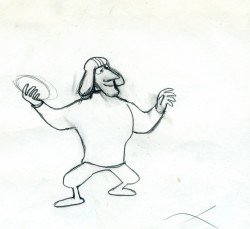

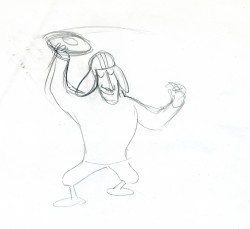

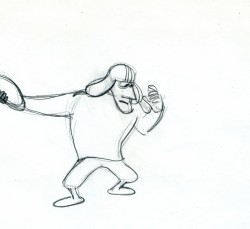

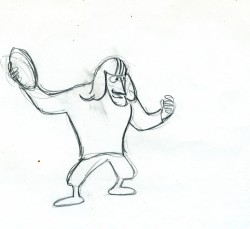

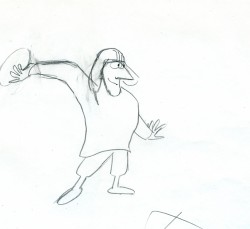

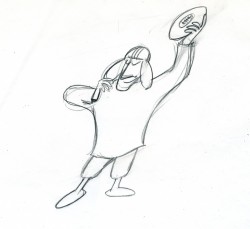

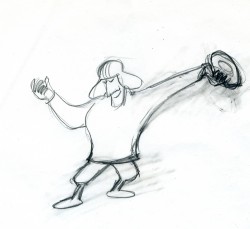

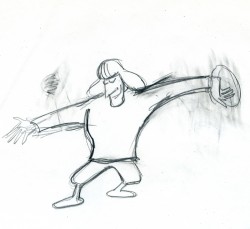

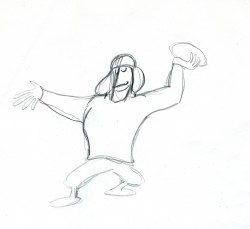

- Here’s an interesting short cycle that Tissa David animated for Letterman. Letterman, himself, plays with a football.

Tissa often animated on more limited shows this way. The drawings B1-B6 can work as a short cycle; drawings B1-D25 work as another cycle. She’ll move out of this and come back to it again later. It hides the cycles yet allows you to reuse drawings cleverly. It’s not just a constantly repeating 1-25 as appears here.

1

1  2

2

____________(Cick any image to enlarge to see full frame drawing.)

25

25Letterman flips the ball on threes.

3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 18

18 19

19 20

20 21

21 22

22 23

23 24

24