Monthly ArchiveJune 2009

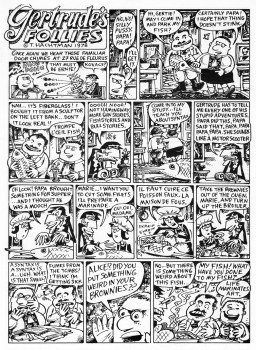

Daily post &SpornFilms &T.Hachtman 20 Jun 2009 08:04 am

Gertrude – Recap

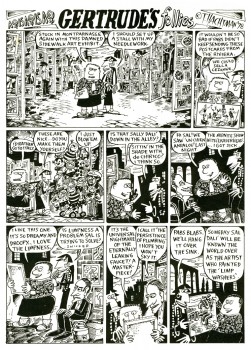

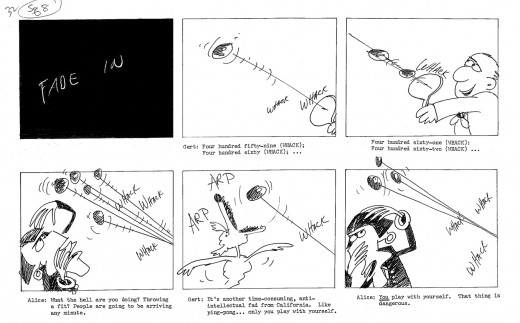

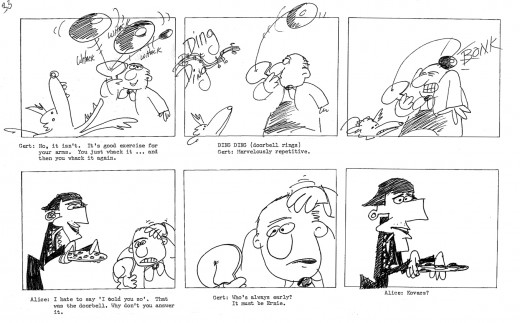

- Back in the late ’70s, there was a local newspaper that competed with the Village Voice for the alternative audience. The Soho News was smaller and thinner, but had its own treasures. Some good writing and listings, and many excellent alternative comic strips. (Bill Plympton had a weekly strip in this paper before he started animating.)

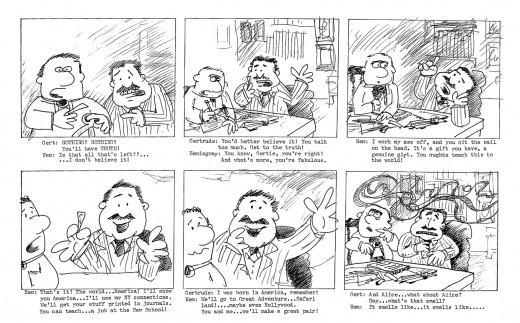

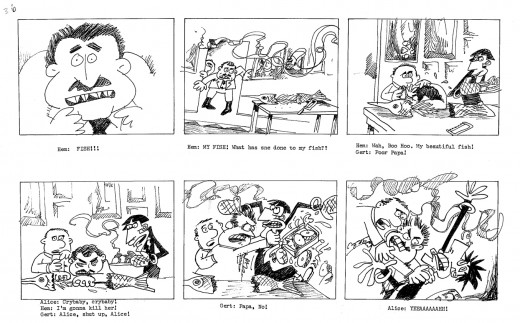

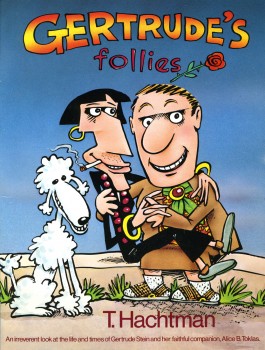

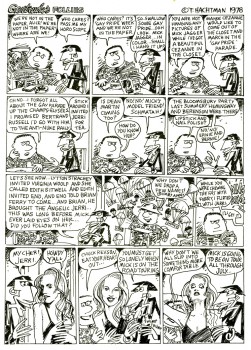

I fell in love with one comic strip called Gertrude’s Follies to the point where I waited  each week for the new issue and the new strip to hit to market. It was about Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas and all the crazies that came into their lives – particularly Picasso, Hemingway and other iconic art types. It didn’t matter that Matisse and Capote didn’t meet; they were both available for the strip – as was everyone else.

each week for the new issue and the new strip to hit to market. It was about Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas and all the crazies that came into their lives – particularly Picasso, Hemingway and other iconic art types. It didn’t matter that Matisse and Capote didn’t meet; they were both available for the strip – as was everyone else.

Finally, after enjoying it for so long, I decided to locate the cartoonist behind it, and see whether he was interested in developing a storyboard and script for a feature. Maybe we could get some low-budget financing.

Tom Hachtman was the cartoonist, and he was a brilliant artist. His wife, Joey Epstein, was another fine artist. The two entered my life at this point, and some interesting things developed.

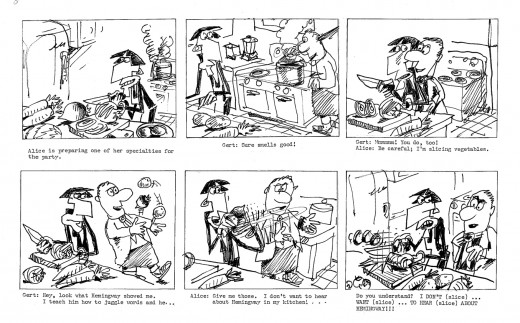

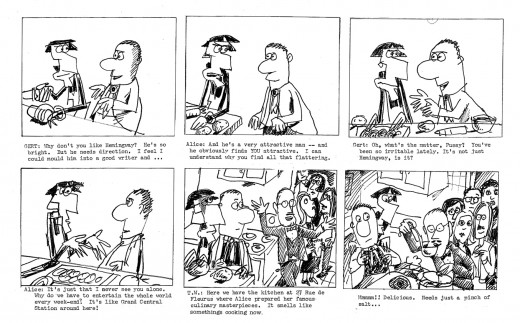

Gertrude’s Follies was an ongoing project. Tom worked with Maxine Fisher, who has been my writing partner through all the years of my studio. The two of them developed a couple of themes from the mass of strips that had been done and started to weave a storyboard. Tom left 4 or 5 panels of each 6 panel page empty, and I constructed and reconstructed story around them. Sometimes I would draw more material, sometimes I would take some away. It was real fun.

The Soho News folded, and no one really picked up the strip. It ran for a short time in The Advocate. Tom was able to publish a collected book (see the cover above.) You can still locate a rare copy on line.

Some newer, color copies of the strip can be found on line here.

Tom also does some political cartoons for the site here.

The movie never went into production. I couldn’t raise the funds – my inexperience. We did make one short segment – a two minute piece that was the most hilarious strip. Sheldon Cohen, an animator I met at the Ottawa 76 festival, came to NY when I offered him a job on Raggedy Ann. Sheldon, ultimately, did a number of films for the National Film Board which you can watch on-line if you click on his name.

The movie never went into production. I couldn’t raise the funds – my inexperience. We did make one short segment – a two minute piece that was the most hilarious strip. Sheldon Cohen, an animator I met at the Ottawa 76 festival, came to NY when I offered him a job on Raggedy Ann. Sheldon, ultimately, did a number of films for the National Film Board which you can watch on-line if you click on his name.

Sheldon animated this particularly funny strip. It took a while for him to animate it, and by the time he was finished, the feature had died and I had lost some interest. Years later I inked and painted it and had it shot. The short piece was never finished, though I still think about doing that.

Aside from Gertrude, both Tom & Joey worked on a number of my films and still infrequently do. The two have painted many murals on the Jersey Coast, where they currently live. Tom has been a political cartoonist for the NY Daily News, has done lots of airbrush work for Bob Blechman when the Ink Tank was in operation. He also has done quite a few cartoons for The New Yorker magazine.

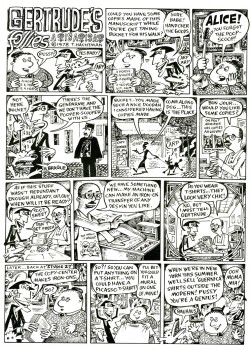

Here are a few of the strips to give you the flavor. Perhaps next week I’ll give a sample of our storyboard, comparing it with some of the actual strips. Enjoy.

1

1  2

2

(Click on any image to enlarge so that you can read the strips.)

We worked up a storyboard and script for a feature. It was a bit of a rush since I found the distributor of a low budget comedy film who asked for something similar in animation. I thought we could get him interested. I wanted to strike while the iron was hot. The guy didn’t get it, thought it wasn’t funny, didn’t even understand it. His company folded six months later. A one hit wonder.

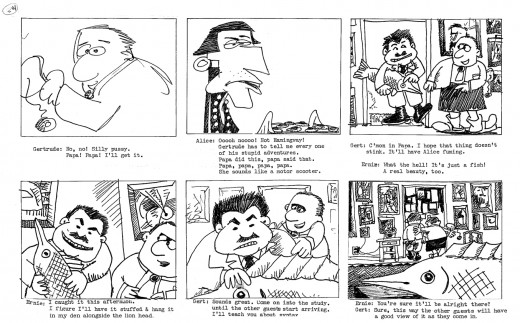

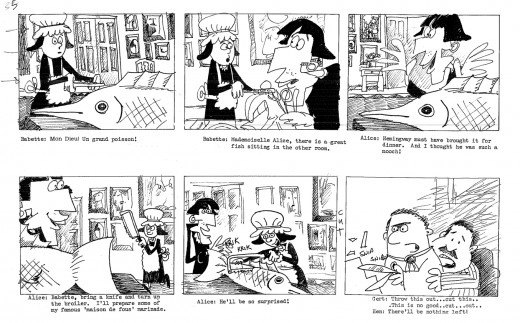

We tried to stay close to many of the strips and found a direction.

Here are two weeklies from the strip.

(Click on any image to enlarge.)

The equivalent part of the storyboard follows. To give a short syopsis of the story thus far:

Trying to be somewhat current, we built the story around an upcoming, all-encompassing exhibit Picasso was going to have at the Museum of Modern Art. At the same time, Gertrude had just sent off a big book to her agent in NY. A party was in order, and we join them in this section of the storyboard as they prepare for the party. There’s a guided tour going on at the house as they prepare, and Hemingway arrives early.

(This is about 20 mins into the film.)

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Hubley &Models 19 Jun 2009 07:19 am

Carousel’s Lovers

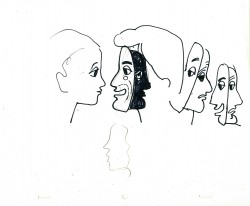

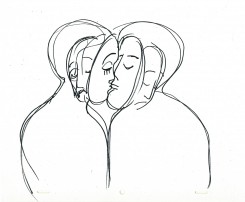

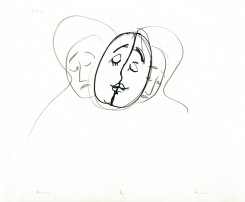

- Let’s take a look at the scene in Hubley’s Everybody Rides the Carousel

- Let’s take a look at the scene in Hubley’s Everybody Rides the Carousel

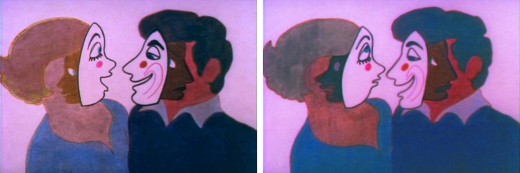

wherein the young lovers have had a spat and push on to have a romantic scene despite the fact that neither of them wants to do that.

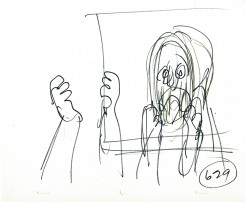

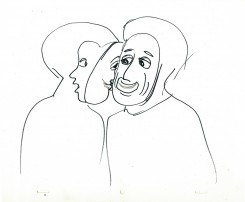

They’ve argued over the girl having cut her hair without telling the boy. He’s annoyed and she laughs at him. They push on to a frothy conversation. Both put on masks to continue the conversation while the inner characters

are annoyed and have an inner monologue. They get to the point where they can’t take the masks off and end plling away from each other.

are annoyed and have an inner monologue. They get to the point where they can’t take the masks off and end plling away from each other.

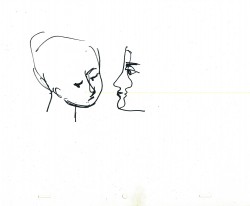

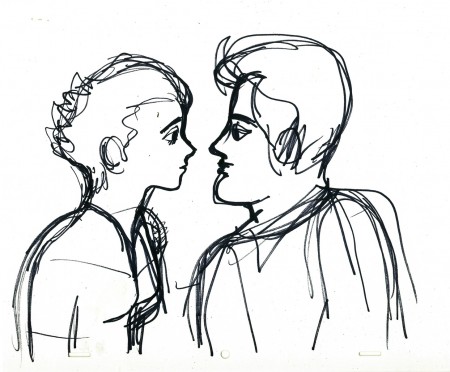

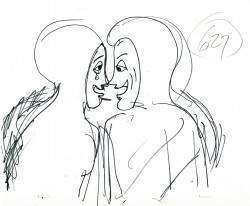

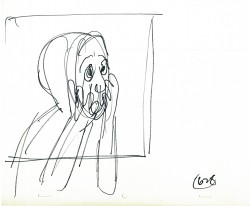

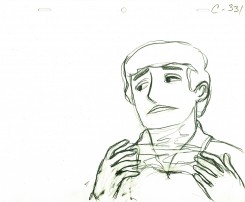

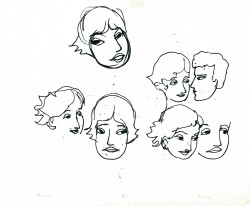

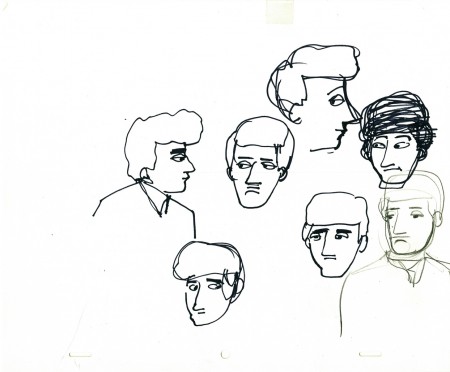

I’ve gathered John Hubley’s layouts for this sequence. Tissa David animated them. You’ll note that the pencil numbers are a scene breakdown done in Tissa’s handwriting. The very loose drawings were done with a sharpie or pencil. The pencils would have been done while in handing it to Tissa during the conversation. They’re to delineate some point in greater detail for her.

I’ve also pulled some frame grabs so you can see how it was finally rendered. The coloring was done on vellum and shot bottom light. No more than 3 levels were used (including the background.) Tissa, aside from concerning herself with the dramatics of the scene, had to watch that the characters didn’t overlap. More complication for her.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

By the way, this was Meryl Streep’s first screen performance.

Charles Levin, another NY character actor, played the boy.

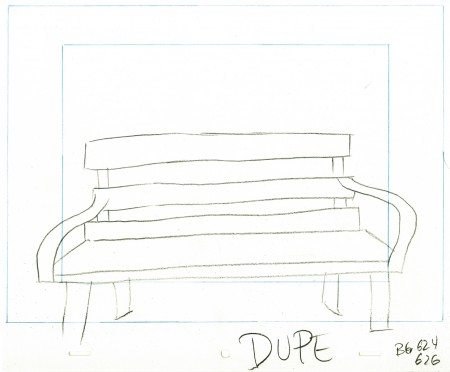

Here’s the park bench.

A quick rough copy by me to Tissa of John’s Bg LO.

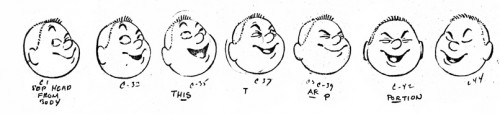

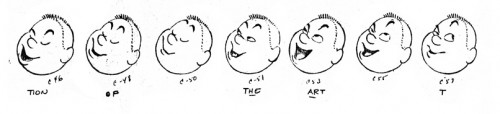

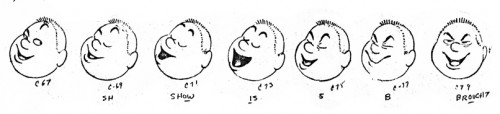

John’s model of the boy’s head for Tissa.

Daily post 18 Jun 2009 07:38 am

$9.99 Opening/Snow White/Norstein

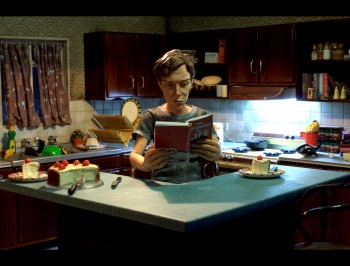

- Tatia Rosenthal‘s animated feature has its New York premiere tomorrow evening at the Landmark Sunshine Cinemas at 143 East Houston Street (view map).

- Tatia Rosenthal‘s animated feature has its New York premiere tomorrow evening at the Landmark Sunshine Cinemas at 143 East Houston Street (view map).

From the director, who certainly wants to celebrate:

“If you go to see it this Friday at 8:15 (tickets should be on sale soon on Fandango or on the theater’s website) we can all go after for drinks. I’ll be there to lead the way. I’m thinking La Linea or One and One – both on first Av. and First street. See you Friday!”

The film, in case you don’t know as yet, is a stop-motion animated feature based on the book by Etgar Keret, a series of short stories. Ms. Rosenthal raised the money from Israel and directed the animation in Australia. It includes an all-star cast including Geoffrey Rush (who recently won the Tony Award for Exit the King) and Anthony LaPaglia.

There was a good article in the NYTimes last Friday.

An informative interview with Tatia Rosenthal appears in Film Monthly, and there is an interview with writer, Etgar Keret, in the NYPress.

Hopefully there will be plenty more press with this opening.

The film’s official website can be found here.

Needless to say, this film is not getting quite the same marketing push that UP is getting, and the filmmaker needs as many to show up this weekend as possible to keep the film alive and thriving. Get off your bum, as they say, and go see it. It’s going to be raining all weekend anyway; perfect time for a movie.

- I’d like to suggest a brilliant website with some awe inspiring artwork that you won’t see elsewhere. Most of it, currently, is from Disney’s Snow White, and you get to realize what a remarkable film that was. The Cowan Collection is just a treat for people like me. Such a wealth of material. I also suggest you leave a comment. It’s disheartening to put a lot of work into a site to have no feedback.

- There’s an interview with Yurij Norstein at the Animatsiya in English site. This is what the Art of it is all about. Thank you Niffiwan.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 17 Jun 2009 07:39 am

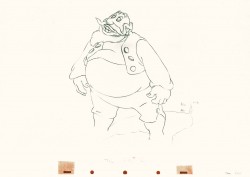

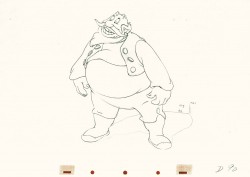

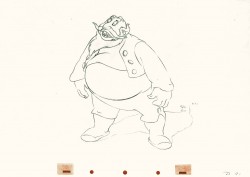

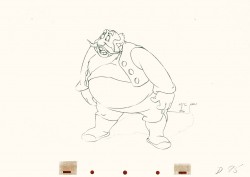

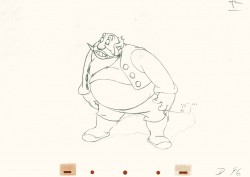

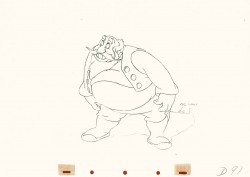

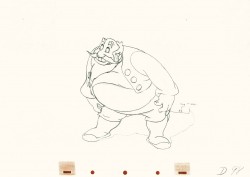

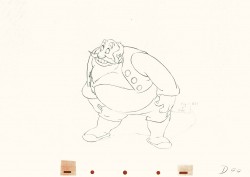

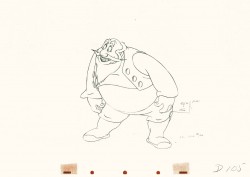

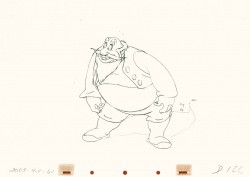

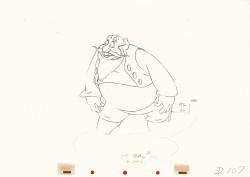

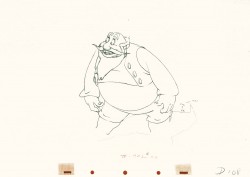

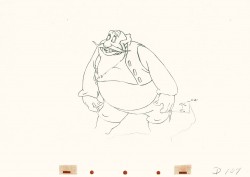

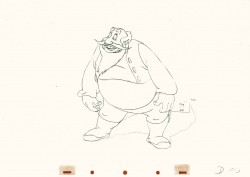

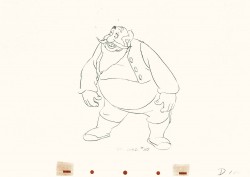

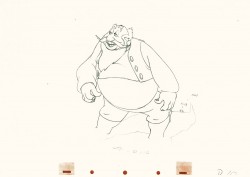

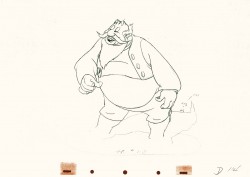

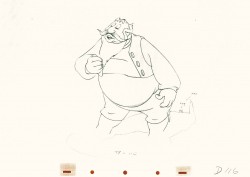

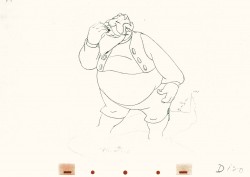

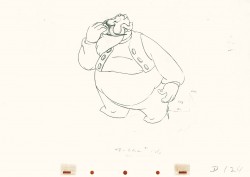

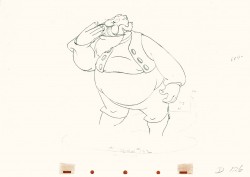

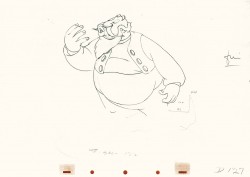

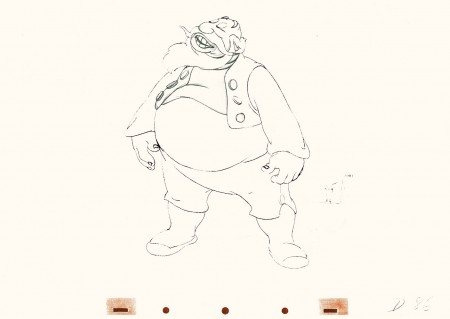

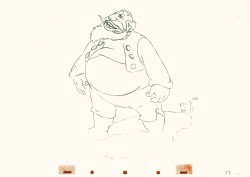

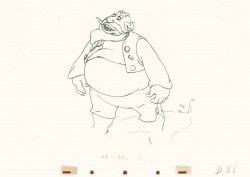

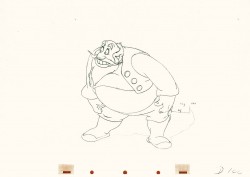

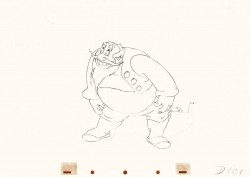

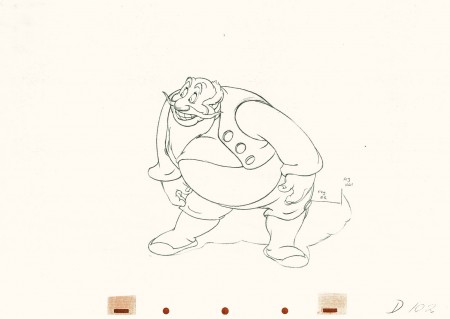

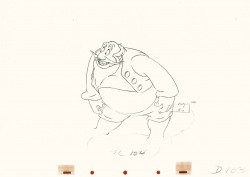

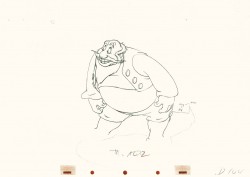

Tytla’s Stromboli 3

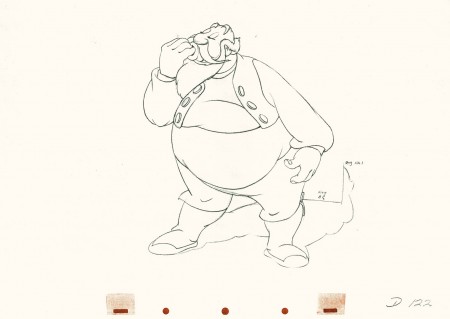

- This is part 3 of this large scene by Bill Tytla of Stromboli. The scene started in Part 1 with thoroughly frenetic anger from Stromboli. In Part 2 he tries to catch himself and get a grip on his emotions. Here in Part 3 he moves slowly and takes a 180° turn from where he started. The line against the curve. All this while playing out the lines from the scene. The drawing is stunning, the motion is brilliant, and the acting is the best animation has to offer. Those hands are just great; look at 126.

I pick up with the last drawing from Part 2.

86

86(Click any image to enlarge.)

87

87 88

88

Tytla made sure he firmly planted Stromboli’s feet (in part 2)

before he attempted this firm bow.

101

101

He’s made a solid line of the back, the strength of this move,

by using the left arm held firmly in place.

102

102

This is the bottom of the bow, now he goes back up.

104

104

All of the shapes change naturally in the bow, though it looks

as if it remains a solid. No noticeable change. Solid weight.

122

122

Watch the timing on the hand from here to #128

as Stromboli blows a kiss.

Many an animator today would pop it and call it animation.

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

Articles on Animation 16 Jun 2009 08:52 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film 2

- Last week, I posted a short piece on British animation in 1957. This came from a Journal that was released (in the days before ASIFA) on the International state of the animated film.

- Last week, I posted a short piece on British animation in 1957. This came from a Journal that was released (in the days before ASIFA) on the International state of the animated film.

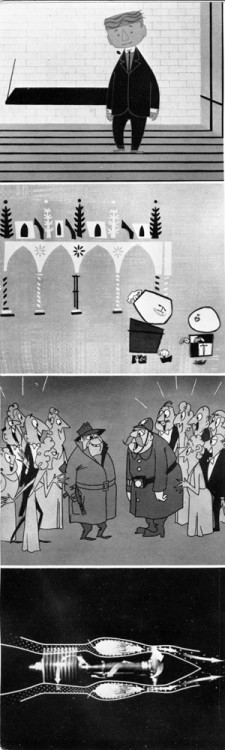

The Journal coincided with the “first International animated film festival in Britain” at the National Film Theatre during February and March 1957.

They screened some 150 films, including 12 of the 31 features produced to that time.

The hope for the festival was to encourage theatres to include animated shorts on their programs again. The art form was dwindling. At that time, no one saw television as the panacea it would become.

This document gathered seven different writers and filmmakers to write about the state of animation in the respective countries.

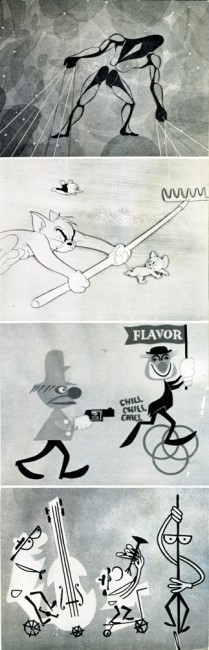

AT THE Cannes Film Festival in the spring of 1956 I overheard a ticket taker remark to a puzzled tourist who evidently had tried unsuccessfully to get into the premiere of one of the full length feature presentations, “II y a aussi des petites dessins-animes.” Judging from the tone in which he spoke, half condescending, half affectionate, his words seemed to imply “tough luck, but as a consolation there are some little cartoons to be seen if you care to have a look.” He was referring to the International Festival of Animated Films which was taking place at the same time in another part of the cinema Palais. His attitude was similar to that of the general run of movie-goer everywhere. The cartoon is usually considered a

pleasing little hors d’oeuvre to be enjoyed along with more substantial fare. That this hors d’oeuvre is welcome is apparent in the little murmurs of anticipated delight which still run through most audiences when the faces of Pluto, Mickey Mouse or Mr. Magoo come on to the screen. It is as though the audience realizes that for a few minutes they will be spared the sensational horrors which so often appear in the newsreel, or the tired cliches of a third rate travelogue. With the cartoon the audience can enter into a realm of pure fantasy, in which the laws of gravity are nonexistent, where pain is not pain and where characters become symbols or stereotypes, not to be taken very seriously.

pleasing little hors d’oeuvre to be enjoyed along with more substantial fare. That this hors d’oeuvre is welcome is apparent in the little murmurs of anticipated delight which still run through most audiences when the faces of Pluto, Mickey Mouse or Mr. Magoo come on to the screen. It is as though the audience realizes that for a few minutes they will be spared the sensational horrors which so often appear in the newsreel, or the tired cliches of a third rate travelogue. With the cartoon the audience can enter into a realm of pure fantasy, in which the laws of gravity are nonexistent, where pain is not pain and where characters become symbols or stereotypes, not to be taken very seriously.

The audience which strayed in to see the animated films at Cannes (the tickets were free) bore little resemblance to the self-conscious, publicity hungry international set which attended the gala openings of the longer features. The cartoons were attended by the producers themselves, a motley crew from every corner of the earth, and casual spectators from the streets, curious and unprejudiced. It was interesting to watch the reaction of this audience to films which ranged all the way from animated folk tales of Texas to heavy political propaganda from both sides of the iron curtain. The actor who drew the most spontaneous outburst of laughter was that ageless veteran whose career has remained unchanged throughout the years, Mr. Donald Duck. His frustration in the film which so delighted the audience was caused by his ineffectual efforts to fall asleep in spite of a relentless neon light which kept flashing off and on, and the insistent sound of dripping water from a tap which gradually increased in his imagination until each drop seemed a bomb visibly shaking the whole earth with rhythmic concussions. Donald’s frustration, seemed on that afternoon in Cannes to be such a note of understanding which reached across the

To Your Health, Tom & Jerry________barriers of language and nationality. This particular

Balentine Beer commercial,_________film was, as always with Disney, elaborately anima-

Winston Cigarette commercial_______ted, no economy tricks employed, no corners cut.

_______________________________The sound track with its metamorphosis of dripping water to world-shaking “booms” was imaginative and appropriate to the medium. Also, like most of Disney’s films, it was a sample of the usual over-cute style with background drawings similar to the easiest kind of commercial advertising.

It is impossible to consider the animated film in the United States without thinking first of Disney. After 30 years his name is still synonymous with the short cartoon in the minds of most of the American movie-audience. Sometimes during the long period since his first exciting Silly Symphonies appeared, the work from his large organisation in California seemed to have sunk into the doldrums. Formula replaced invention. The medium lost its initial public appeal. Disney’s excursions into the field of “live action” have been sometimes rewarding, sometimes disappointing. Some of the wild life films have recaptured the excitement of his early cartoons, while the romantic historic costume pieces have often seemed banal. Always a clever  showman, he has recently built a large fun fair, or amusement park in California which serves also as a setting for television programme material. When, from time to time, a new feature length cartoon appears, such as Lady and The Tramp, in which the chief characters are dogs, one is amazed at the technical slickness of the animation and annoyed by the weak story line, which seems to be influenced by the wish to include every sure-fire box-office trick. This approach does not lead to any fresh experiments within the medium.

showman, he has recently built a large fun fair, or amusement park in California which serves also as a setting for television programme material. When, from time to time, a new feature length cartoon appears, such as Lady and The Tramp, in which the chief characters are dogs, one is amazed at the technical slickness of the animation and annoyed by the weak story line, which seems to be influenced by the wish to include every sure-fire box-office trick. This approach does not lead to any fresh experiments within the medium.

It was the short film Gerald McBoing-Boing which first brought a radical change of style to the attention of the public in America and soon after to the cinema-goers in Europe. This highly original short film, produced by U.P.A. Pictures, with finely integrated music by Gail Kubik and with sophisticated visual elements, seemed to satisfy a public at that time weary of the Disney formula. The talented minds which produced “Gerald” had made previous cartoons in which visual wit and economical animation had replaced the elaborately evolved techniques established by the larger studios, but these films had never been seen in the theatres. Some of the U.P.A. men had worked previously in the Disney Studios. The organisation under the leadership of Stephen Busustow has now expanded into the field of television. Robert Cannon, one of the most brilliant U.P.A. directors, brings a fertile imagination and fresh approach to each new film he creates. Another director, Pete Burness, who has been with the U.P.A. since its early days, has created a now popular cartoon character, Mr. Magoo, whose blithe innocence and near-sightedness leads him unscathed and unconcerned through the violence of the modern world. Mr. Magoo, like Donald Duck, has become a beloved international personality.

The U.P.A. style, according to their own spokesmen, derives from “modern” art. It is uncluttered, flat and often linear. The characters do not seem bound by any natural physical laws of movement. Perhaps one of the greatest contributions of the U.P.A. is that they have shown the public that the less realistic a movement is, the more creditable it becomes optically. Disney sometimes bases the movement of his characters on live action models, as with Alice in Alice in Wonderland. The greater the effort to imitate realistic movement, the more apt one is to be aware of the stroboscopic nature of the medium, the more jittery the result. If legs are used to express the symbol of walking, rather than the imitation of walking, the illusion of movement is more acceptable, a paradox which indicates the validity of the “modern” art approach. Like any device this simplification can be carried too far. If the human figure becomes too abstract it may lose all its expressive power. Usually the U.P.A. figures, moving flatly on a flat screen are consistent, humorous and convincing.

Magoo Beats the Heat , Madeline

Less effective have been certain of the U.P.A. attempts to animate the drawings of “big name” illustrators, such as Thurber and Bemelmans. The Unicorn in the Garden and Madeline are examples. Since the quality of both Thurber’s and Bemelmans’ drawings depends on a subtlety and unevenness of line which is impossible to use in the animation technique, where every celleloid must have an almost mechanical similarity, the flavour of the original is lost and the result is far less successful than the work of lesser known artists, whose training within the film medium has taught them its restrictions.

Nevertheless, the U.P.A. has been a healthy influence in the United States. The proof that a new style has had its effect on Disney and his imitators is seen in their efforts to modernise their own productions. Disney has released a short history of music called Whistle, Toot, Plunk and Boom, which seemed to imply that if his studios wished, they too could work in the “modern” style. The popular M.G.M. films, with incredibly fast pacing and surrealist gags, seem also to have cancer research or democracy. Which does not mean that good films cannot be made on these themes. But there is little chance for the individual to produce a genuinely experimental film on his own subject.

It is difficult to say what the future of this medium in the U.S. will be. At present animation is still popular in the entertainment fields and in commercial television. Some of the most imaginative uses of animation at present are in one-minute TV commercials. Animation is in demand in those sponsored industrial films where a mechanical concept can be shown more clearly than it can in live-action. Animation is also useful in industrial films which try to express abstract ideas or fantasy.

Donald Duck, in his better movements, still communicates to an international audience. It would be interesting to speculate, however, as to what animation might have been if Disney had not had his enormous influence. In the first place, animation might not necessarily have been only cartoon. The simplest visual element, a dot, or a line, can become a dancing symbol and convey an idea, an association. These ideas could be developed with other means than by conventional story telling. The film need not always be based on a literary concept. It could be, for the spectator, an experience like seeing dancing, or hearing music. Within the medium not only new forms, but new ways of expression could be evolved. The animated film need not always be a pastische, a sequence of gags or a fairy tale. It could be a powerful medium. It is condensed and potent. Like most potent things, it is better in small doses. But in a brief time it can pack a terrific punch. In the end its possibilities are limited only by the imagination of the filmmaker.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Models 15 Jun 2009 07:27 am

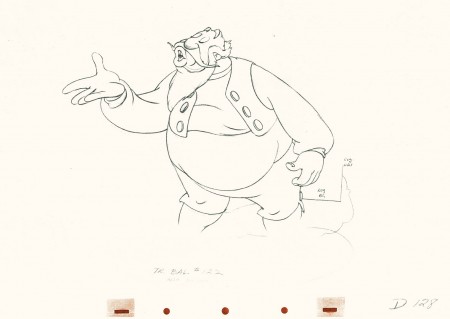

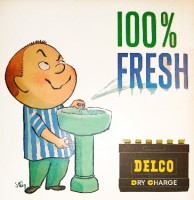

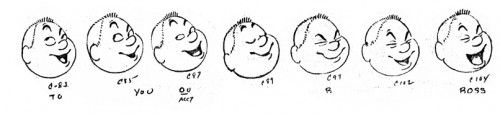

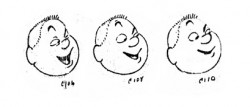

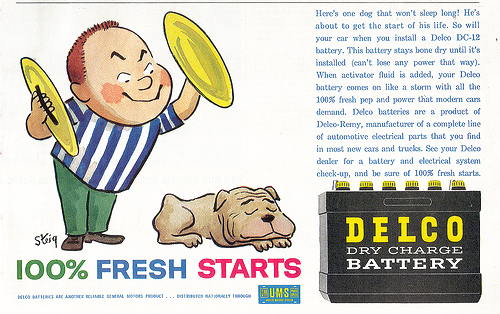

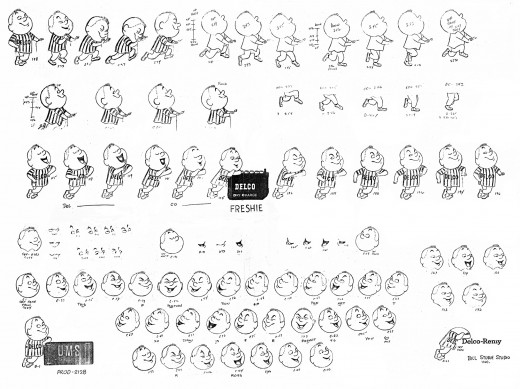

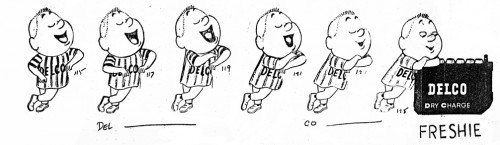

Steig’s Delco

- In 1959 Delco Remy batteries featured a spokesman of a character who was everywhere, that year. William Steig designed the tough-kid for the campaign, and he did ads for all the magazines – Look, Life, Saturday Evening Post. This was an obvious offshoot of Steig’s very successful book of cartoons, Small Fry, which was originally published in 1944 but had had quite a bit of success for the cartoonist.

This was years before Steig would write and illustrate his first children’s book.

Naturally enough, there were animated ads done as well.

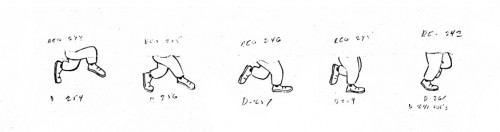

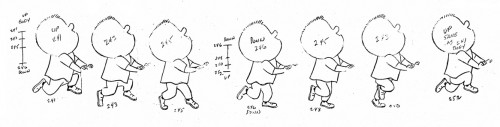

Here’s a model sheet made for a Delco battery spot for the Bill Sturm studio in 1959. Sturm was an ex-Fleischer animator who moved into the Fletcher-Smith studio and advertising animation in 1947. He had his onw studio as early as 1956.

This model sheet was created, as many feature models are made, by taking clippings of some completed animation. The character was by William Steig, and I’m not sure who did the animation, but Jim Logan did the assisting.

(Click any image to enlarge,)

Too large to take in all at once, let’s break the animation down to its parts:

“Freshie” leans on the battery talking.

Then he starts to push the battery (which is on its own level.)

The skip is broken into levels with the upper half on one . . .

. . . and the lower half on another.

I’m not sure what this chart was used for, unless this was a series of spots, and the art from the first was what they were shooting for in subsequent spots.

Regardless, a lot of work went into this one minute spot. I’m not sure how much Steig gave them to match his models, but I would assume it was substantial (based on other spots he’d done.)

Photos 14 Jun 2009 08:15 am

Sundayphoto Clocks

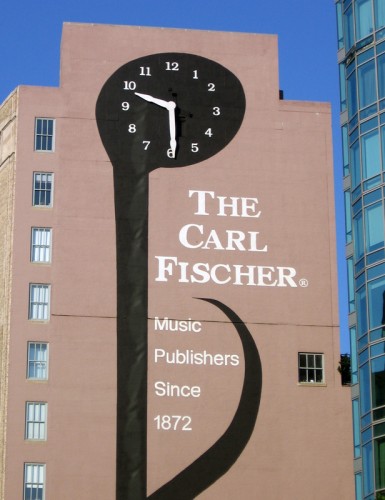

- I recently ran into a brand new clock that was built into a local building. This took me by surprise; it’s not something that architects are currently incorporating into their buildings.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

It’s a simple clock, nothing ornate, but it did the job.

I began to look for other clocks on my path in Manhattan. There aren’t too many. Yes, there are some notables like the clocks at Grand Central or Penn Station. But I was looking for the ordinary. Then I saw one in Queens in Astoria.

It wasn’t very pretty, but there it was. This gave me the idea of mentioning it to my friend, Steve Fisher, who lives in Maspeth, Queens. I thought he might have more than I on his path. He did. These are the clocks he found:

From Steve: Off I went in search of clocks. Close to home,

there are two clocks on the Maspeth Federal Savings Bank building

in Maspeth that are less than remarkable, but it was a start.

A drive into Manhattan led me to my old stomping grounds, Cooper Union.

Parking a few blocks south of Astor Place on the Bowery, I immediately

came across an outdoor restaurant with a neat clock.

You can also see Cooper’s clock in the distance of the above image.

Across from the school, on the west side of Fourth Ave, the clock on the

Carl Fischer building has not worked from at least 1969

when I first attended Cooper.

The clock has been cleaned up, but, trust me, it still doesn’t work.

I like the fact that you can view its hand from along the face of the building.

A little further up town, at 14th Street, there is a great clock

on each face of the Con Ed Building (is it still called that?)

Heading back toward Queens, I came upon this clock atop a building on Houston Street near Essex Street. Its face numbers are very playful. (Sorry about the lack of sharpness – it was extremely hazy at that moment.)

I took this photo of the HSBC’s clock (the building once had a terrific

domed interior space) while driving across the Williamsburg Bridge)

Finally, I came across this one today on 69th Street back in Queens.

I liked the way the blue-green glow of the clocks picks up the green

signal light. And notice the times are close, but not exactly the same.

Commentary 13 Jun 2009 07:17 am

Who’s watching?

- About a year ago, a film of mine was accepted by a film festival. The festival contact called asking what age group te film was made for. I’ve often been asked this question and have always answered it uncomfortably. At times I’ll answer for the 6-12 year old age group; at other times I’ll just say family audiences – the same as The Lion King. Lately, I’ve been saying it was made for me – I don’t give them my age group.

- About a year ago, a film of mine was accepted by a film festival. The festival contact called asking what age group te film was made for. I’ve often been asked this question and have always answered it uncomfortably. At times I’ll answer for the 6-12 year old age group; at other times I’ll just say family audiences – the same as The Lion King. Lately, I’ve been saying it was made for me – I don’t give them my age group.

The question has been a sore spot for me my whole career. I don’t deny that my films are designed for children. That means I try to keep the film somewhat PC, but then I’d do the same if the film were made for 60 year olds. I’m not into making films that are designed to be offensive – no farts, no cigarettes, no foul-mouthed characters. I don’t see the point of it. It’s not because I’m trying to be a good role model for children; it’s because I don’t think films need these things.

Citizen Kane and Vertigo couldn’t be more adult, yet there’s not much offensive on the screen. Why bother, unless you’re trying to make a point?

I thought of this problem, for me, with a recent post on Jenny Lerew‘s Blackwing Diaries. She responds to a letter to the editor at the NYTimes regarding the review of Up by Manohla Dargis.

Jenny’s right; the film is not just for kids. Regardless of whether you like dislike or have problems with the film, it’s not really designed for a targeted audience other than the filmmakers, themselves. The problem is that it’s an animated film, and the notion still exists in the general public that all animated films are specifically designed for children.

This, however, might cause some problems. I did a film called Whitewash back in 1994. (It plays on HBO Family all month during July:

This, however, might cause some problems. I did a film called Whitewash back in 1994. (It plays on HBO Family all month during July:

7/ 5 4:40 pm, 7/ 6 5:25 am,

7/10 3:05 pm, 7/15 3:55 pm,

7/18 3:30 pm, 7/21 8:30 pm,

7/27 3:45 pm – all EST, adjust for your time zone.)

This was a tough one. It was a docudrama done for HBO which responded to a couple of actual events.

There were two black children, brother & sister, in the Bronx who were attacked by a white street gang. They were spray-painted white and sent off, humiliated. After a bit of research I found several other variants on the same news story. A Puerto Rican child, in the same neighborhood, also spray-painted white. There was more recently a Korean child spray-painted black by a black gang in Brooklyn.

What’s the audience for this? I treated it with the greatest sensitivity I could, hired an important African-American playwright, Ntozake Shange, to write the initial script based on

my treatment. I added lots of improvised dialgue by children. I designed it, with the help of the brilliant Bridget Thorne, as a dirty-street colored film after variants of hip-hop art. I wanted my beloved New York City to look dirty. It was.

my treatment. I added lots of improvised dialgue by children. I designed it, with the help of the brilliant Bridget Thorne, as a dirty-street colored film after variants of hip-hop art. I wanted my beloved New York City to look dirty. It was.

I underplayed the actual attack showing no real physical violence. The one person in my studio who animated in the most Disney-like tradition was cast by me to animate the attack. I didn’t want it to be or look real, and I didn’t mind that it stood out from the rest of the movie.

Yet,when the film played at a children’s program in Ottawa – lots of cute cartoons and mine – a father three minutes into the movie grabbed his 3/4 year old child and raced from the theater. Bravo! I was pleased to see that one father acted responsibly. Yet, it’s often bothered me that that parent had to make the decision in the middle of such a program, advertised as children’s films. The film won a number of big awards – the Humanitas prize for best screenplay for children as well as the Crystal Heart Award at the Heartland Film Festival. Both are family oriented Christian organizations that take responsible filmmaking seriously.

However, after the Ottawa experience, I chose to keep the film out of festivals when I thought the same might happen. I’ve shown it at retrospectives of mine and at adult film festivals (it’s been very successful), but I won’t put parents in harm’s way again. It’s not fair.

Another film of mine, Champagne, tells the story (in documentary style) of a child who was raised in a convent because her mother had committed murder and was incarcerated. The film has one short violent scene. This has not stopped me from submitting it to any festival that wants it. It’s a positive, hopeful and uplifting short, and I have no compunction in showing it to anyone – child or adult.

I guess, in the end, I have to say that filmmakers HAVE to make the best film they can (even if it includes flatulence) but they should also have a conscience about who the films are made for. The film has to be honest and clear, but it also has to live in our society.

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Hubley 12 Jun 2009 08:10 am

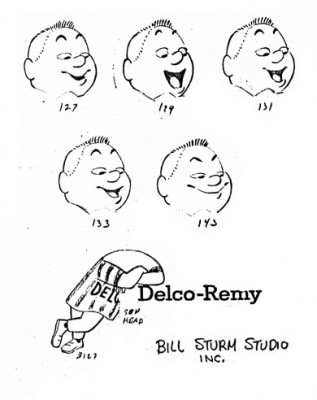

Johnny Gent’s Spellbinder

Johnny (Gentilella) Gent had the hardest time on the Letterman series done for the original Electric Company. He could never get the characters and kept trying to add 3D form to the 2D characters that John Hubley had created.

Johnny (Gentilella) Gent had the hardest time on the Letterman series done for the original Electric Company. He could never get the characters and kept trying to add 3D form to the 2D characters that John Hubley had created.

It was my first job, and I was in awe of every animator that walked through ________A very early John Hubley model of Spellbinder.

the door. We had 2½ months to do

all the artwork on the 20 spots that were 2½ mins each. A total of 50 mins in 10 weeks. (That’s about right these days for a 30 second spot!)

I did all the assisting, inking and inbetweening and had to do it quickly. (I estimated about 18 secs. per drawing. The game I played with myself to keep up was to keep one eye on the drawing and another on the clock.)

As I said, it was my first animation job. What did I know! I had to take Johnny’s drawings and reshape them into Hubley’s characters, and I had to do it in ink. No pencil tests. Just do it. Whatever came out, was the final artwork (and I use that word loosely.) I felt, even while I was doing it, that I was killing Johnny’s work, and I ultimately apologized for it. No one else complained, so it went as it did.

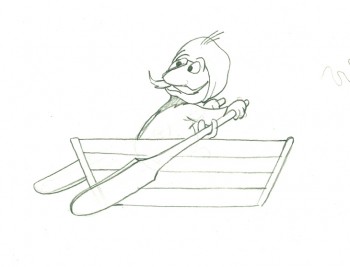

Here’s a cycle of Johnny Gent’s Spellbinder rowing a boat.

1

1(If you click on any drawing it’ll show you the full animation page.

Johnny Gent’s Spellbinder rows a boat

on two’s per drawing indicated

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

Articles on Animation 11 Jun 2009 07:46 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

Needless to say, these are all outdated pieces, but there’s some entertainment (at least) to be gathered from reading these reports. The first, naturally enough, came from Great Britain and – appropriate to the times – is Halas & Batchelor-centric.

All of the essays talk about the effect UPA has had on the medium, most particularly Phillip Stapp’s report of the USA. (I’ll probably post that one next week.)

Here’s the state of England in 1957:

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

In Britain, animation is a family business, operating in the style of the medieval craftsmen’s guilds. The Units tend to stay together in small communities, usually in converted houses or tiny offices. Personnel grow up with their production companies, often entering the business direct from University or Art School. Training is done by experience, as the young learn from the old in the day-to-day work at the animation tables. There is a struggle to maintain continuity of production. Leadership is based on the personality of one or two people who often manage the whole operation as a kind of family concern, imposing their style to a degree which they themselves would scarcely admit, for many strive to encourage as much individual experiment as possible amongst those who work for them.

The Units are divided into four main categories. First, there are the groups who produce sponsored films but, because they have been in existence for a long time and have established some measure of independence, are able to conduct occasional experiments that lead to theatrical distribution, or even to produce films specifically for the entertainment market. Halas and Batchelor Productions are a Unit of this kind.

John Halas came to this country before the War, having worked in Hungary with George Pal; Joy Batchelor first met him in London and shared in the making of animation films, both here and in Budapest. They married and now operate the company under joint control. Like most British Units, they depend on sponsorship of various forms for their existence. This comes from three main sources:

Mr. Finley’s Feelings, Earth is A Battlefield, __1. Official Bodies, Government Departments

Britvic Commercial, The Gas Turbine. ______or International Authorities.

_____________________________________Examples of films made recently in this category include To Your Health, for the World Health Organisation: Basic Fleetwork, for the Admiralty; The Sea, for the Ford Foundation; and The Candlemaker, for the United Lutheran Church in America.

2. Sponsorship through Industry. Recent films include: Power to Fly, for the British Petroleum Company, and Invisible Exchange for Shell.

3. Direct Advertisments, made now mainly for Commerical Television. Halas and Batchelor made the famous Murraymints series, as well as a special series for Dunlop.

Using the resources gained over years of work in the “bread-and-butter” business, Halas and Batchelor have been able to amuse themselves (and very large cinema audiences) with such pictures as their delightful History of the Cinema, which was chosen for the Royal Film Performance in 1956. Of a more serious character was the feature length Animal Farm, a rare example of an attempt to use the cartoon film for the interpretation of a complicated political satire. The Unit that made these films is now ninety strong; it is run personally by John Halas and Joy Batchelor, both of whom are active at every stage in the making of the films as well as handling the complicated business problems that arise in sustaining the flow of the sponsorship so essential to their continued existence. The shaping of spiralling movements around little twirls of Matyas Seiber’s clever wood-wind orchestrations in well-known tunes is characteristic of their work, as well as a love of perky, bouncing little men who tackle everything from Income Tax forms to oil-well drilling with a gay, impertinent but pleasing confidence.

Halas and Batchelor produced the first feature-length cartoon in this country (Animal Farm), the first stereoscopic experiment in animation (The Owl and the Pussycat), and the first major puppet-animation production (Figurehead). Ever since their formation in 1940, they have remained completely independent of any financial links with other organisations.

The second type of Unit in Britain is that devoted entirely to sponsored work, but taking full advantage of the chances offered them by enlightened business concerns to experiment. The William Larkins Studio, operated by Geoffrey Sumner and Theodore Thumwood, was started in 1942 under the name of Analysis Films. It became part of the Film Producer’s Guild in 1947 and, as Larkins Studio, has since produced about 820 short animated films. There are seventy people in the Unit, which turns out about 30,000 feet of final-cut material a year. Personnel tends to remain static, and the Unit’s tradition in training can be gathered from the fact that, on a recent prize-winning film, the average age of the production team was 23.

As in the case of Halas and Batchelor, :ertain of their films have broken through to he theatrical field, although they have not so ~ar made films except to order. Men of Merit, “or example, was shown in some 3,000 cinemas in this country alone; 602 copies were printed by Technicolor. The studio’s style is still, perhaps almost unconsciously, influenced by the work of Peter Sachs, notably by his angular figures, clear-cut lines and sharply-defined backgrounds, in which detail is reduced to a minimum. Earth is a Battlefield, their current production, has a clever extension of the technique in a series of disjointed, cut-out figures which perform to a sound track in the rhyming style of Enterprise, an earlier film by Peter Sachs.

The third main type of animation Unit is exemplified by Nicholas and Mary Spargo’s group at Henley-on-Thames. Formed to produce material specifically for Commercial Television, the Unit now consists of eleven people working in a large room over a shop in the centre of the town. Following the well-established pattern, there are already two trainees in the group, working on the fifteen, thirty- and fifty-second commercials for which the Unit was set up. Because they are lively and imaginative, work flows at a fast pace; Nicholas Spargo spends much of his time on the business side at the moment, while his wife is usually to be found in the studio. Both gained their experience in the tough school of the David Hand Unit at Cookham.

In addition to the independent units, there are a number of small animation groups in Britain attached to certain large organisations like the Shell Film Unit. Francis Rodker and a small team of specialists have been producing excellent diagrams and animated sections for the Shell Unit since its formation in 1935. Three animation cameras are in use, each producing about 4,000 feet of exposed film a year.

A Short Vision, Down a Long Way

Finally, there are the experimental groups, whose status borders between professional and amateur. Typical is the case of Joan and Peter Foldes, who produce animated films in their own home in Edgware. Peter Foldes, like John Halas, came to London from Hungary; he met his wife here and they now work together on all their films. Animated Genesis, their first film, was made on their own resources up to picture rough-cut stage. It was then shown to the British Film Institute, who persuaded Sir Alexander Korda to see it; he completed the sound track and gave the picture distribution through British Lion. A Short Vision, the six-minute story of an artist’s impression of the world destroyed by nuclear fission, was also made as a private venture in the beginning; it was completed with the help of the British Institute’s Experimental Production Fund, and later shown on American television.

The personal quality of British animation films derives from the struggle for independence, the imprint of a beneficent sponsorship and the style of those who founded their own groups and continue to run them. The system is not without drawbacks. Experiment, especially in subject matter, is always subordinate to the needs of the sponsor. Full public screenings are the exception, however delicate the advertisement. The Units are too busy with their own work to indulge in large-scale publicity. They have to contend with the fact that the major circuits are, by-and-large, completely deaf to their work. By contrast many European countries encourage the work of their animation units.

In spite of these difficulties, British animated films have won many international awards. These films are being used increasingly in the United States, both in the cinemas and over television. The battle for a screening is being won at long last; in every country, except Britain.