Yearly Archive2009

Photos 14 Jun 2009 08:15 am

Sundayphoto Clocks

- I recently ran into a brand new clock that was built into a local building. This took me by surprise; it’s not something that architects are currently incorporating into their buildings.

(Click any image to enlarge.)

It’s a simple clock, nothing ornate, but it did the job.

I began to look for other clocks on my path in Manhattan. There aren’t too many. Yes, there are some notables like the clocks at Grand Central or Penn Station. But I was looking for the ordinary. Then I saw one in Queens in Astoria.

It wasn’t very pretty, but there it was. This gave me the idea of mentioning it to my friend, Steve Fisher, who lives in Maspeth, Queens. I thought he might have more than I on his path. He did. These are the clocks he found:

From Steve: Off I went in search of clocks. Close to home,

there are two clocks on the Maspeth Federal Savings Bank building

in Maspeth that are less than remarkable, but it was a start.

A drive into Manhattan led me to my old stomping grounds, Cooper Union.

Parking a few blocks south of Astor Place on the Bowery, I immediately

came across an outdoor restaurant with a neat clock.

You can also see Cooper’s clock in the distance of the above image.

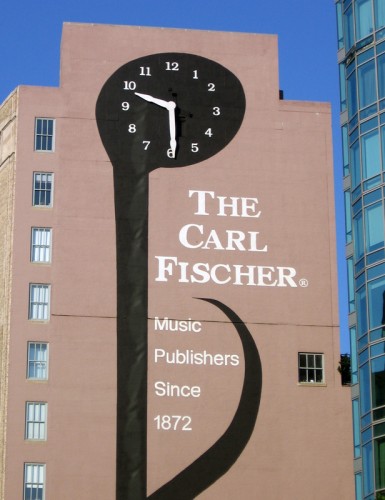

Across from the school, on the west side of Fourth Ave, the clock on the

Carl Fischer building has not worked from at least 1969

when I first attended Cooper.

The clock has been cleaned up, but, trust me, it still doesn’t work.

I like the fact that you can view its hand from along the face of the building.

A little further up town, at 14th Street, there is a great clock

on each face of the Con Ed Building (is it still called that?)

Heading back toward Queens, I came upon this clock atop a building on Houston Street near Essex Street. Its face numbers are very playful. (Sorry about the lack of sharpness – it was extremely hazy at that moment.)

I took this photo of the HSBC’s clock (the building once had a terrific

domed interior space) while driving across the Williamsburg Bridge)

Finally, I came across this one today on 69th Street back in Queens.

I liked the way the blue-green glow of the clocks picks up the green

signal light. And notice the times are close, but not exactly the same.

Commentary 13 Jun 2009 07:17 am

Who’s watching?

- About a year ago, a film of mine was accepted by a film festival. The festival contact called asking what age group te film was made for. I’ve often been asked this question and have always answered it uncomfortably. At times I’ll answer for the 6-12 year old age group; at other times I’ll just say family audiences – the same as The Lion King. Lately, I’ve been saying it was made for me – I don’t give them my age group.

- About a year ago, a film of mine was accepted by a film festival. The festival contact called asking what age group te film was made for. I’ve often been asked this question and have always answered it uncomfortably. At times I’ll answer for the 6-12 year old age group; at other times I’ll just say family audiences – the same as The Lion King. Lately, I’ve been saying it was made for me – I don’t give them my age group.

The question has been a sore spot for me my whole career. I don’t deny that my films are designed for children. That means I try to keep the film somewhat PC, but then I’d do the same if the film were made for 60 year olds. I’m not into making films that are designed to be offensive – no farts, no cigarettes, no foul-mouthed characters. I don’t see the point of it. It’s not because I’m trying to be a good role model for children; it’s because I don’t think films need these things.

Citizen Kane and Vertigo couldn’t be more adult, yet there’s not much offensive on the screen. Why bother, unless you’re trying to make a point?

I thought of this problem, for me, with a recent post on Jenny Lerew‘s Blackwing Diaries. She responds to a letter to the editor at the NYTimes regarding the review of Up by Manohla Dargis.

Jenny’s right; the film is not just for kids. Regardless of whether you like dislike or have problems with the film, it’s not really designed for a targeted audience other than the filmmakers, themselves. The problem is that it’s an animated film, and the notion still exists in the general public that all animated films are specifically designed for children.

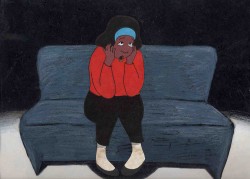

This, however, might cause some problems. I did a film called Whitewash back in 1994. (It plays on HBO Family all month during July:

This, however, might cause some problems. I did a film called Whitewash back in 1994. (It plays on HBO Family all month during July:

7/ 5 4:40 pm, 7/ 6 5:25 am,

7/10 3:05 pm, 7/15 3:55 pm,

7/18 3:30 pm, 7/21 8:30 pm,

7/27 3:45 pm – all EST, adjust for your time zone.)

This was a tough one. It was a docudrama done for HBO which responded to a couple of actual events.

There were two black children, brother & sister, in the Bronx who were attacked by a white street gang. They were spray-painted white and sent off, humiliated. After a bit of research I found several other variants on the same news story. A Puerto Rican child, in the same neighborhood, also spray-painted white. There was more recently a Korean child spray-painted black by a black gang in Brooklyn.

What’s the audience for this? I treated it with the greatest sensitivity I could, hired an important African-American playwright, Ntozake Shange, to write the initial script based on

my treatment. I added lots of improvised dialgue by children. I designed it, with the help of the brilliant Bridget Thorne, as a dirty-street colored film after variants of hip-hop art. I wanted my beloved New York City to look dirty. It was.

my treatment. I added lots of improvised dialgue by children. I designed it, with the help of the brilliant Bridget Thorne, as a dirty-street colored film after variants of hip-hop art. I wanted my beloved New York City to look dirty. It was.

I underplayed the actual attack showing no real physical violence. The one person in my studio who animated in the most Disney-like tradition was cast by me to animate the attack. I didn’t want it to be or look real, and I didn’t mind that it stood out from the rest of the movie.

Yet,when the film played at a children’s program in Ottawa – lots of cute cartoons and mine – a father three minutes into the movie grabbed his 3/4 year old child and raced from the theater. Bravo! I was pleased to see that one father acted responsibly. Yet, it’s often bothered me that that parent had to make the decision in the middle of such a program, advertised as children’s films. The film won a number of big awards – the Humanitas prize for best screenplay for children as well as the Crystal Heart Award at the Heartland Film Festival. Both are family oriented Christian organizations that take responsible filmmaking seriously.

However, after the Ottawa experience, I chose to keep the film out of festivals when I thought the same might happen. I’ve shown it at retrospectives of mine and at adult film festivals (it’s been very successful), but I won’t put parents in harm’s way again. It’s not fair.

Another film of mine, Champagne, tells the story (in documentary style) of a child who was raised in a convent because her mother had committed murder and was incarcerated. The film has one short violent scene. This has not stopped me from submitting it to any festival that wants it. It’s a positive, hopeful and uplifting short, and I have no compunction in showing it to anyone – child or adult.

I guess, in the end, I have to say that filmmakers HAVE to make the best film they can (even if it includes flatulence) but they should also have a conscience about who the films are made for. The film has to be honest and clear, but it also has to live in our society.

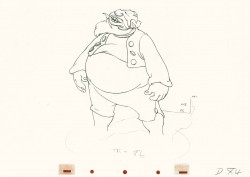

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Hubley 12 Jun 2009 08:10 am

Johnny Gent’s Spellbinder

Johnny (Gentilella) Gent had the hardest time on the Letterman series done for the original Electric Company. He could never get the characters and kept trying to add 3D form to the 2D characters that John Hubley had created.

Johnny (Gentilella) Gent had the hardest time on the Letterman series done for the original Electric Company. He could never get the characters and kept trying to add 3D form to the 2D characters that John Hubley had created.

It was my first job, and I was in awe of every animator that walked through ________A very early John Hubley model of Spellbinder.

the door. We had 2½ months to do

all the artwork on the 20 spots that were 2½ mins each. A total of 50 mins in 10 weeks. (That’s about right these days for a 30 second spot!)

I did all the assisting, inking and inbetweening and had to do it quickly. (I estimated about 18 secs. per drawing. The game I played with myself to keep up was to keep one eye on the drawing and another on the clock.)

As I said, it was my first animation job. What did I know! I had to take Johnny’s drawings and reshape them into Hubley’s characters, and I had to do it in ink. No pencil tests. Just do it. Whatever came out, was the final artwork (and I use that word loosely.) I felt, even while I was doing it, that I was killing Johnny’s work, and I ultimately apologized for it. No one else complained, so it went as it did.

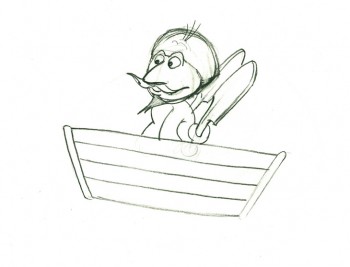

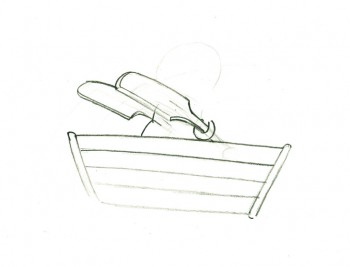

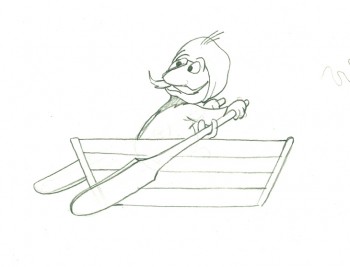

Here’s a cycle of Johnny Gent’s Spellbinder rowing a boat.

1

1(If you click on any drawing it’ll show you the full animation page.

Johnny Gent’s Spellbinder rows a boat

on two’s per drawing indicated

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

Articles on Animation 11 Jun 2009 07:46 am

Journal of Int’l Animated Film

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

- In 1957, the British Film Academy, directed by Roger Manvell, published a short “Journal” which included reports from a number of writers around the world talking about the animation industries in their respective countries. Somewhat similar to the ASIFA International Bulletins we receive quarterly.

Needless to say, these are all outdated pieces, but there’s some entertainment (at least) to be gathered from reading these reports. The first, naturally enough, came from Great Britain and – appropriate to the times – is Halas & Batchelor-centric.

All of the essays talk about the effect UPA has had on the medium, most particularly Phillip Stapp’s report of the USA. (I’ll probably post that one next week.)

Here’s the state of England in 1957:

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

IN America, most animation work is linked with the major studios. Tom and Jerry come from the M.G.M. studios, Popeye from Paramount, Tweety Pie from Warners; even the U.P.A. unit works under the general umbrella of Columbia, whilst Disney’s is almost a separate major studio in itself.

In Britain, animation is a family business, operating in the style of the medieval craftsmen’s guilds. The Units tend to stay together in small communities, usually in converted houses or tiny offices. Personnel grow up with their production companies, often entering the business direct from University or Art School. Training is done by experience, as the young learn from the old in the day-to-day work at the animation tables. There is a struggle to maintain continuity of production. Leadership is based on the personality of one or two people who often manage the whole operation as a kind of family concern, imposing their style to a degree which they themselves would scarcely admit, for many strive to encourage as much individual experiment as possible amongst those who work for them.

The Units are divided into four main categories. First, there are the groups who produce sponsored films but, because they have been in existence for a long time and have established some measure of independence, are able to conduct occasional experiments that lead to theatrical distribution, or even to produce films specifically for the entertainment market. Halas and Batchelor Productions are a Unit of this kind.

John Halas came to this country before the War, having worked in Hungary with George Pal; Joy Batchelor first met him in London and shared in the making of animation films, both here and in Budapest. They married and now operate the company under joint control. Like most British Units, they depend on sponsorship of various forms for their existence. This comes from three main sources:

Mr. Finley’s Feelings, Earth is A Battlefield, __1. Official Bodies, Government Departments

Britvic Commercial, The Gas Turbine. ______or International Authorities.

_____________________________________Examples of films made recently in this category include To Your Health, for the World Health Organisation: Basic Fleetwork, for the Admiralty; The Sea, for the Ford Foundation; and The Candlemaker, for the United Lutheran Church in America.

2. Sponsorship through Industry. Recent films include: Power to Fly, for the British Petroleum Company, and Invisible Exchange for Shell.

3. Direct Advertisments, made now mainly for Commerical Television. Halas and Batchelor made the famous Murraymints series, as well as a special series for Dunlop.

Using the resources gained over years of work in the “bread-and-butter” business, Halas and Batchelor have been able to amuse themselves (and very large cinema audiences) with such pictures as their delightful History of the Cinema, which was chosen for the Royal Film Performance in 1956. Of a more serious character was the feature length Animal Farm, a rare example of an attempt to use the cartoon film for the interpretation of a complicated political satire. The Unit that made these films is now ninety strong; it is run personally by John Halas and Joy Batchelor, both of whom are active at every stage in the making of the films as well as handling the complicated business problems that arise in sustaining the flow of the sponsorship so essential to their continued existence. The shaping of spiralling movements around little twirls of Matyas Seiber’s clever wood-wind orchestrations in well-known tunes is characteristic of their work, as well as a love of perky, bouncing little men who tackle everything from Income Tax forms to oil-well drilling with a gay, impertinent but pleasing confidence.

Halas and Batchelor produced the first feature-length cartoon in this country (Animal Farm), the first stereoscopic experiment in animation (The Owl and the Pussycat), and the first major puppet-animation production (Figurehead). Ever since their formation in 1940, they have remained completely independent of any financial links with other organisations.

The second type of Unit in Britain is that devoted entirely to sponsored work, but taking full advantage of the chances offered them by enlightened business concerns to experiment. The William Larkins Studio, operated by Geoffrey Sumner and Theodore Thumwood, was started in 1942 under the name of Analysis Films. It became part of the Film Producer’s Guild in 1947 and, as Larkins Studio, has since produced about 820 short animated films. There are seventy people in the Unit, which turns out about 30,000 feet of final-cut material a year. Personnel tends to remain static, and the Unit’s tradition in training can be gathered from the fact that, on a recent prize-winning film, the average age of the production team was 23.

As in the case of Halas and Batchelor, :ertain of their films have broken through to he theatrical field, although they have not so ~ar made films except to order. Men of Merit, “or example, was shown in some 3,000 cinemas in this country alone; 602 copies were printed by Technicolor. The studio’s style is still, perhaps almost unconsciously, influenced by the work of Peter Sachs, notably by his angular figures, clear-cut lines and sharply-defined backgrounds, in which detail is reduced to a minimum. Earth is a Battlefield, their current production, has a clever extension of the technique in a series of disjointed, cut-out figures which perform to a sound track in the rhyming style of Enterprise, an earlier film by Peter Sachs.

The third main type of animation Unit is exemplified by Nicholas and Mary Spargo’s group at Henley-on-Thames. Formed to produce material specifically for Commercial Television, the Unit now consists of eleven people working in a large room over a shop in the centre of the town. Following the well-established pattern, there are already two trainees in the group, working on the fifteen, thirty- and fifty-second commercials for which the Unit was set up. Because they are lively and imaginative, work flows at a fast pace; Nicholas Spargo spends much of his time on the business side at the moment, while his wife is usually to be found in the studio. Both gained their experience in the tough school of the David Hand Unit at Cookham.

In addition to the independent units, there are a number of small animation groups in Britain attached to certain large organisations like the Shell Film Unit. Francis Rodker and a small team of specialists have been producing excellent diagrams and animated sections for the Shell Unit since its formation in 1935. Three animation cameras are in use, each producing about 4,000 feet of exposed film a year.

A Short Vision, Down a Long Way

Finally, there are the experimental groups, whose status borders between professional and amateur. Typical is the case of Joan and Peter Foldes, who produce animated films in their own home in Edgware. Peter Foldes, like John Halas, came to London from Hungary; he met his wife here and they now work together on all their films. Animated Genesis, their first film, was made on their own resources up to picture rough-cut stage. It was then shown to the British Film Institute, who persuaded Sir Alexander Korda to see it; he completed the sound track and gave the picture distribution through British Lion. A Short Vision, the six-minute story of an artist’s impression of the world destroyed by nuclear fission, was also made as a private venture in the beginning; it was completed with the help of the British Institute’s Experimental Production Fund, and later shown on American television.

The personal quality of British animation films derives from the struggle for independence, the imprint of a beneficent sponsorship and the style of those who founded their own groups and continue to run them. The system is not without drawbacks. Experiment, especially in subject matter, is always subordinate to the needs of the sponsor. Full public screenings are the exception, however delicate the advertisement. The Units are too busy with their own work to indulge in large-scale publicity. They have to contend with the fact that the major circuits are, by-and-large, completely deaf to their work. By contrast many European countries encourage the work of their animation units.

In spite of these difficulties, British animated films have won many international awards. These films are being used increasingly in the United States, both in the cinemas and over television. The battle for a screening is being won at long last; in every country, except Britain.

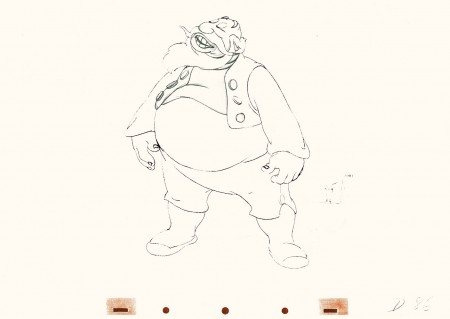

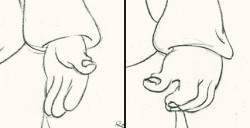

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney 10 Jun 2009 07:34 am

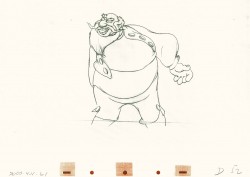

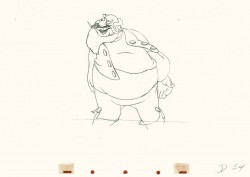

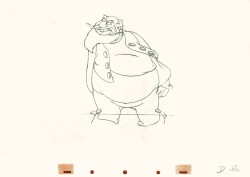

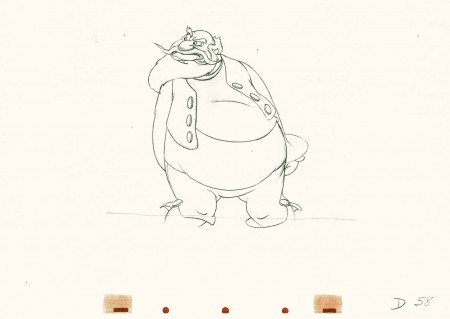

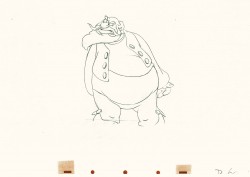

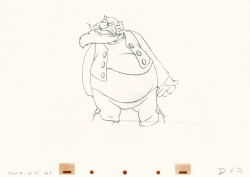

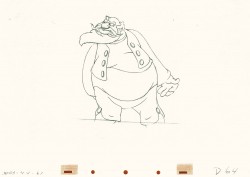

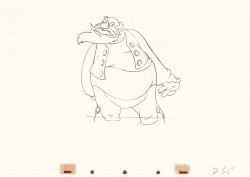

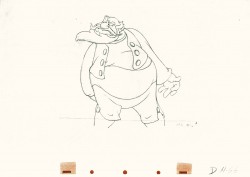

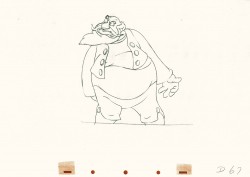

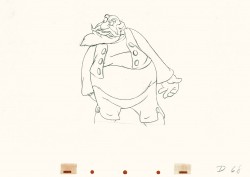

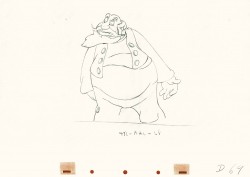

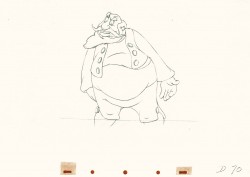

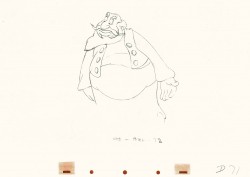

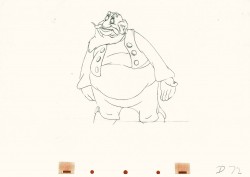

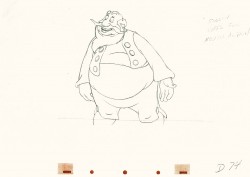

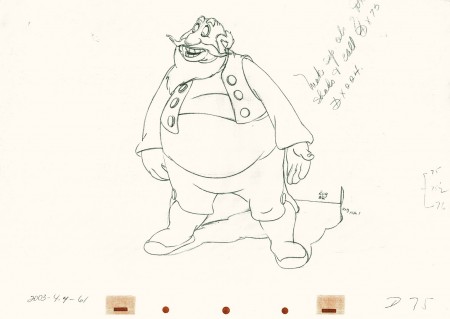

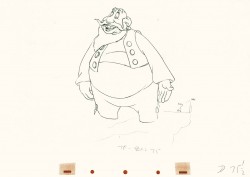

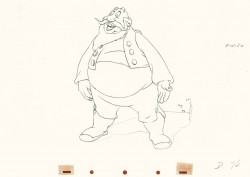

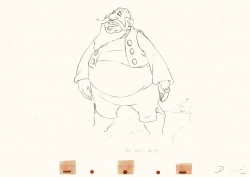

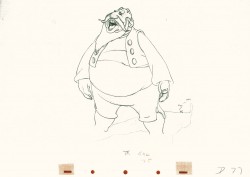

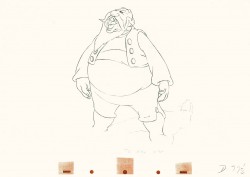

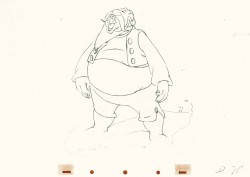

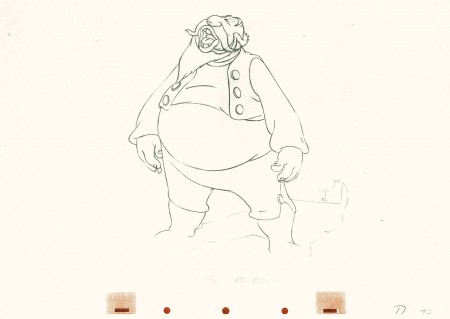

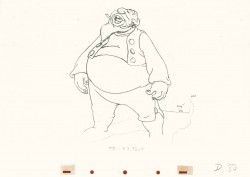

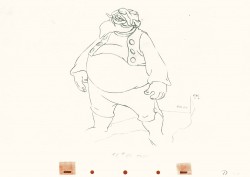

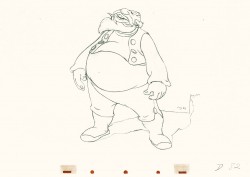

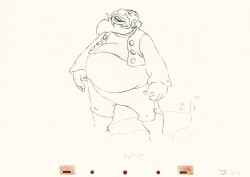

Tytla’s Stromboli 2

This note arrived from Borge Ring after my first post Bill Tytla’s scene featuring Stromboli’s mood swing:

- The Arch devotees of Milt Kahl have tearfull misgivings about Wladimir Tytla’s magnificent language of distortions. ‘”Yes, he IS good. But he has made SO many ugly drawings”

Musicologists will know that Beethoven abhorred the music of Johan Sebastian Bach.

yukyuk

Børge

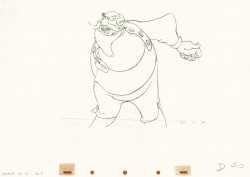

My first post spoke a bit about the distortion Tytla would use to his advantage to get an emotional gesture across. It’s part of the “animating forces instead of forms†method that Tytla used. This is found in Stromboli’s face in the first post. In this one look for this arm in drawing #50. It barely registers but gives strength to the arm move before it as his blouse follows through in extreme.

There’s also some beautiful and simple drawing throughout this piece. Stromboli is, basically, a cartoon character that caricatures reality beautifully. A predecessor to Cruella de Vil. In drawings 76 to 80 there’s a simple turn of the hand that is nicely done by some assistant. A little thing among so much bravura animation.

There’s also some beautiful and simple drawing throughout this piece. Stromboli is, basically, a cartoon character that caricatures reality beautifully. A predecessor to Cruella de Vil. In drawings 76 to 80 there’s a simple turn of the hand that is nicely done by some assistant. A little thing among so much bravura animation.

Many people don’t like the exaggerated motion of Stromboli. However, I think it’s perfectly right for the character. He’s Italian – prone to big movements. He’s a performer who, like many actors in real life, goes for the big gesture. In short his character is all there – garlic breath and all. It’s not cliched and it’s well felt and thought out. Think of the Devil in “Night on Bald Mountain” that would follow, then the simply wonderful and understated Dumbo who would follow that. Tytla was a versatile master.

Here’s part 2 of the scene:

48

48 49

49(Click any image to enlarge.) The full scene with all drawings.

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

Articles on Animation 09 Jun 2009 06:45 am

Working for Lantz in the ’30s

- 22 years ago, “The Walter Lantz Conference on Animation” was held in LA. There were numerous gatherings and talks about animation on a few sunny days in LA. I got to meet a number of fine people there, but, in my usual shy manner, stayed a bit to myself. I did enjoy the event. I can’t remember going out specifically for that, but I was there just the same. My memory is a bit shaky about it. I know there were other conferences that I didn’t make.

A publication, The Art of the Animated Image was an Anthology that was published by AFI and edited by Charles Solomon. Writers such as John Canemaker, Cecile Starr and Donald Crafton wrote for it. The late, great Leo Salkin wrote this short piece which I thought might be interesting to some folks who haven’t seen it.

in the 30′s

A Reminiscence

BY LEO SALKIN

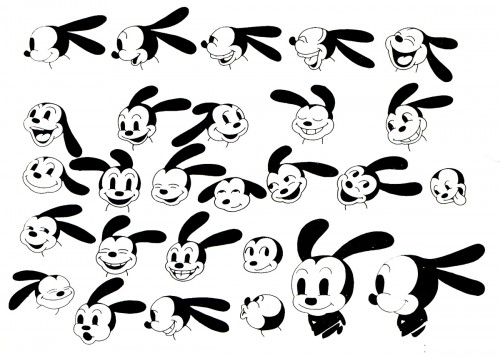

I went to work for Walter Lantz on March 3,1932. At that time he was producing Oswald The Lucky Rabbit cartoons for Universal Pictures. It was my first job. I had had an interview with Walter a couple of weeks earlier; he reviewed my portfolio of cartoons, drawn while I was at Hollywood High, and on the basis of that interview he hired me. It was the era of Prohibition, bathtub ginjohn Held, Jr. drawings, and the Great Depression. I was to be paid $17.50 a week, which seemed to me an enormous sum.

My duties were to wash cels, help in camera, learn to ink and paint, practice inbetweening on my own time. There was no training program: You picked up what you could as .you went along. During that time economic conditions were bad and getting worse, and while you were trying to learn how to ink and paint and flip animation drawings, you were never free of the fear that this job couldn’t last and that at any moment Universal might decide that they didn’t want any more cartoons and the animation department would be closed down. They were scary times but fortunately Walter managed well and we kept going.

Walter Lantz at his drawing table, Universal Pictures, 1928.

In time, I learned how to animate a walk cycle, a run, a squash and stretch action, and something about the mystique of the exposure sheet and animation timing. After awhile I became a pretty good animator. And somewhere along in there I learned about gags. As a matter of fact, there was no way you could have avoided learning about gags: They were the life blood of the place.

What I value most about having worked for Walter in those years is what I learned about gags. The work days in the studio consisted of two major activities: one was making animated cartoons; it was the primary reason we were there, and it was the basis of our livlihood. The second activity, only slightly less important than the first, was drawing cartoon gags of each other. That; was a big thing. And it took place simultaneously with the production of the films. What was remarkable about the situation is that Walter not only tolerated and accepted it, he, at times, contributed and took part in it. And despite the horseplay, production schedules were met and budgets were contained.

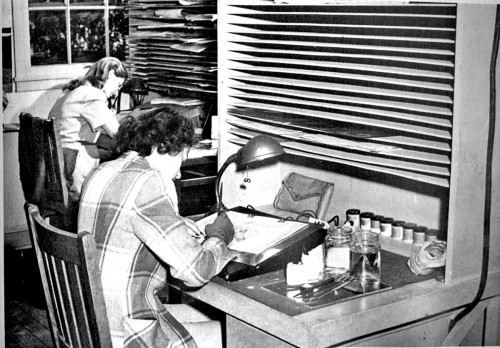

It would be absurd to describe the atmosphere of the place as playful—that’s too refined—it was a funny place. It was a place of gags. The physical environment in which we worked influenced the kind of gags that were played. The animation building was a one-story structure. One side had windows running the length of the building. The interior was divided down the middle by a seven-foot high partition. The ink and paint girls were on the side by the windows—they provided a big part of the audience— and the animation department on the other side was in semi-darkness. It was the semi-darkness that seemed to have nurtured the particular kind of nuttiness that took place.

Inking and painting tables, Universal Pictures.

There were the physical gags like filling a small paper envelope-type of cup with water then pinning it to the bottom side of your animation board so that it slowly dripped on to the crotch of your pants as you were sitting there drawing. Tnere were the eraser gags in which someone would place a piece of rubber eraser on top of the hot light bulb under your animation disc and then wait eagerly for you to become aware of the stench that was enveloping you: There were the hot-foot gags—in fact that was the era of the hot-foot. Most of the guys smoked. Everybody carried matches. The room was in semi-darkness. The entire under-structure of the desks was open: four legs and a cross-piece to put your feet on. Perfect set-up.

And the imbecility went on endlessly. Then there were the belching gags—a standard after-lunch performance: A very loud belch. Voice in the darkness, “Are you okay?” Second voice, “Yeah, I think so.” “You didn’t tear anything, did you?” “No, I’m okay.” “You want some water or something?” “No thanks, but thanks anyway.” “Okay.” Finally, there were the so-called practical jokes which were plentiful, at times painful, embarrassing, humiliating and stupid.

Now we come to a special category which 1 treasure: the personal cartoon gags and caricatures. They were indigenous to the animated cartoon studio. Everybody in the place could draw. The ability to draw was almost a cheap commodity. The personal cartoon gag was the dominant form of communication; people expressed what they felt and observed in cartoons. Anything that happened during the course of the day, however trivial, was potentially the basis of a cartoon. The event could be blown up out of all proportion to what had actually occurred; it could be seen as ridiculous, absurd, pathetic, idiotic, or whatever. The gags were sometimes tasteless, crude, vulgar and obscene,but they generally got laughs.

To analyze why this provided so much pleasure—at least to everyone but the butt of the joke—would require another reading in the psychopathology of humor, and I’d rather avoid that. I think the guys wanted to have fun, to find relief from the boredom of flipping animation paper all day long.

The ability of the artists to create a strikingly recognizable likeness of whoever they were cartooning was extraordinary. Whatever was characteristic and unique about any given person

would be pounced upon, exaggerated and burlesqued, and combined with some personal incident, made a continuing source of cartoon gags and caricatures. Sometimes the way they drew you

would be embarrassing, “My God! I don’t look like that, do I?” And the only person youieould turn to for consolation was Robert Burns:

“O wad some power the giftie give us

To see oursel’s as ithers see us!”

We were granted that.

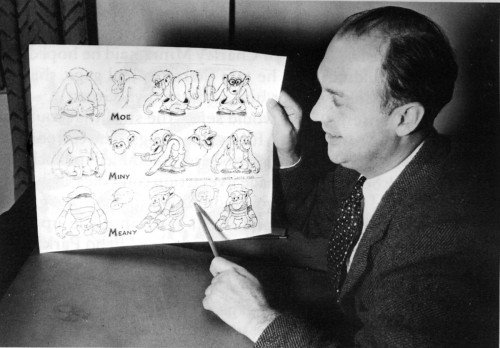

Walter Lantz with a model chart.

This brings me to that stage of development in which I began to learn something about the nature of gags, their structure and function in film. In the early ’30′s Walter Lantz didn’t have a story department. Walt essentially put the stories together with the contributions of a number of people who had shown an ability to think funny and to come up with gags for the films. The way it worked was this: first a subject was chosen: Oswald Camping Out or Oswald at the North Pole or a take-off on King Kong; then a notice was put up on the bulletin board asking those interested to turn in gags; this was followed by a story meeting. The guys called into the meeting were people who had turned in gags—at that time I remember there was Tex Avery, Cal Howard, Jack Carr, me, a few of the key animators, and Walt.

A story meeting, for those who have never attended one, was an extraordinary experience. The prevailing atmosphere was a mood of What the hell, it’s okay to say anything that comes to mind, what’s important is getting laughs. The out-going, extroverted, comic naturals had a hilarious time. For some of us to whom this was unfamiliar territory, the uninhibited, right-off- the-top-of-their-head-shouters were a bit intimidating. There was a lot of talking and laughing and making jokes. Sample joke: in one story meeting I remember Jack Carr, an inveterate punster, who had previously worked for Charley Mintz, said he hoped the Lantz group wouldn’t think he was there to steal gags, that he hoped they wouldn’t consider him a Mintz spy. (Groan).

Out of the nonsense Walt would select the stuff that could be made into a film: comedy bits, funny lines, gags. The cartoons of that period were still being concocted and assembled in much the same way Mack Sennett had made live-action comedies: “Charlie, there’s some kid auto races going on down in Venice—grab a cameraman, go down there and see if you can come up with something funny.” Or, “Hey! They just drained Echo Park Lake, it’s all mud, that oughta be funny as hell!” That’s what we did. We took a locale, an occupation, a situation, or the basic premise of a popular feature and did a lot of gags, strung them together, built in a chase, and got out in under seven minutes.

There was no market testing, or who is our target audience, or will a sponsor buy this? Come on, fellas, it’s just comedy. Get some laughs. Walter was the judge. What he thought was funny was what got up on the screen.

Story meetings despite all the laughter and kidding around had a lot of emotional tension running through them and you had to enjoy doing story to be able to cope with them. Bill Nolan, who co-directed with Walt, was one of the great innovative animators of the late 1920′s period, and he disliked working on story. In fact he hated it, and most of all he hated puns.

We were having a meeting with Bill on a story that Tex Avery, who was then the key animator on the Nolan unit, wanted to develop. It was to be based on a popular song of the period. “I Found a Million Dollar Baby in the Five and Ten Cent Store.” There was the usual amount of banter and gossip and making jokes and Bill was getting increasingly restless, irritated and annoyed. Then someone made a casual remark about how you could sure get some good buys in the dime store, and at that point Jack Carr, the pun man, said, “Right! I mean everybody knows that whatever you get at the five and dime is Woolworth every cent you pay for it!” That did it. The last straw. Bill Nolan jumped up, lunged at Carr and had to be forcefully restrained from punching him out.

Model chart for Oswald The Lucky Rabbit, 1928.

The dynamics of a story meeting were instructive: You were in a competition to be funny, to get laughs. Your mind was totally involved—the right hemisphere, the left hemisphere, the conscious, the pre-conscious, and the unconscious—all trying to come up with that funny bit that would get a laugh. And suddenly you got it. “Wow! Wouldn’t it be funny,” you’d say to yourself, “if Oswald did this and then he did that and then he…” And then you’d stop. “Damn! That’s a gag I saw Chaplin do. I can’t suggest that. I didn’t think it up. That’s stealing.” And right at that moment, somebody else would jump up, say exactly what you were going to say and everybody would laugh and say, “Terrific! Hey, that’s funny!” And you’d be sitting there thinking, “I can’t believe it. Don’t they know that gag was already done by Chaplin or Keaton, or by Harry Langdon or Harold Lloyd?” It was but that was totally irrelevant.

What you had to learn was that it didn’t matter a damn that a piece of business, a comedy bit, a gag, had been done before, and who had done it. Those gags were like common currency, coin of the realm. They belonged to whomever thought of them. And a good memory for gags could be a valuable asset. What made a gag yours was the way you did it. Talented comics made the old stuff look new, mediocrities made it a bore.

You learned your craft as a gag man by doing gags, getting them in a picture, then going to a preview—imagine previewing a cartoon—at the Alexander Theater in Glendale and seeing if they got laughs. There was something ludicrous about the experience, in that the intensity of your emotional involvement didn’t seem justified by the actual event: screening a cartoon. Nobody went to the theater to see a cartoon. At best it was an amusing filler till the feature came on. Big deal. But here you are, sitting there in a cold sweat waiting for the film to unwind, waiting to see if your gag got a laugh. All you’ve got is one gag in the picture. Nobody in that entire theater knows you did it, or even gives a damn. You wait. The gag comes on. If it got a laugh you were ecstatic. Exhilarated. You just sat there in the dark and beamed. If it didn’t get a laugh the failure was personal and embarrassing. “Damn! How could I ever have thought that gag was funny?”

That’s the way it was. A gag got a laugh or it didn’t. The audience was live, there were no laugh tracks to fall back on. There was Walter Lantz and the studio, and you went back to the drawing board and tried again. And again and again.

That was my initiation into the world of cartoons. Walter made that possible. I felt privileged to be there. I used to be delighted when someone I had just met asked me what I did, and I could say,

“I’m in animation—you know, animated cartoons.” Then I would hand them my card which said, “Oswald Cartoons, Universal Pictures,” and there in bright orange, black and white was a smiling Oswald pointing directly to my name.

Animation &Fleischer &Frame Grabs &walk cycle 08 Jun 2009 08:12 am

Betty with Fur walk

- I haven’t posted a Betty Boop walk cycle in some time, so I thought I’d pick on this one. Betty’s walking with a new fur stole, caressing it as she walks. Sweetly animated by Myron Waldman for the film Pudgy Picks a Fight in 1937.

1

1  2

2(Click any image to enlarge.)

Betty wears her new fur.

on ones

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

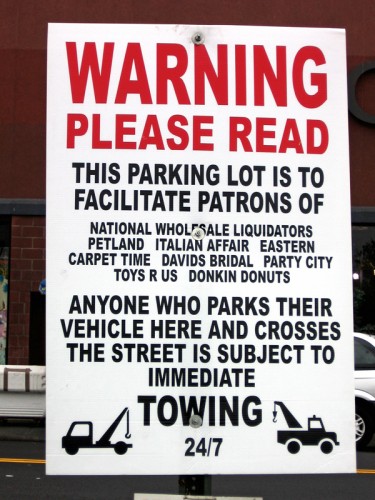

Guest writer &Photos 07 Jun 2009 08:02 am

Signage PhotoSunday

Commentary &Daily post 06 Jun 2009 08:20 am

Spare Change

- Having just posted lots of frame grabs from Bruno Bozzetto’s marvelous film, Allegro Non Troppo, I should have linked to his website. You can find there a page devoted specifically to this feature, as well as to his other two animated features: West and Soda and The VIP: My Brother Superman.

- Having just posted lots of frame grabs from Bruno Bozzetto’s marvelous film, Allegro Non Troppo, I should have linked to his website. You can find there a page devoted specifically to this feature, as well as to his other two animated features: West and Soda and The VIP: My Brother Superman.

You can also find there many hilarious Flash films that Bruno has done. This is some of the best use of Flash that I’ve seen – all for a great laugh. If you’re looking for on-line entertainment – this is it.

- Jeremiah Dickey (who has assisted Emily Hubley on many of her hits) sent this note:

Salutations friends & colleagues in the NYC area,

Salutations friends & colleagues in the NYC area,

Two really superb documentaries for which Emily Hubley & I created animation last year are making their official NY premieres at the Brooklyn Academy of Music this month – come check them out if you can.

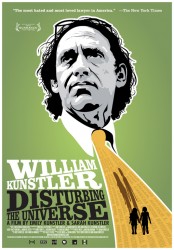

William Kunstler: Disturbing The Universe is a film about the life of the radical lawyer, made by his amazing daughters Sarah and Emily Kunstler. Part of BAMcinemaFEST, it will be screening on Saturday June 20th at 12:30pm, followed by a Q&A with the filmmakers (moderated by DemocracyNOW!’s Amy Goodman).

It will also be screened outdoors the following Thursday June 25th at 9pm in the parking lot across the street from BAM – links to tickets below.

_____6/20 _____6/25

What’s On Your Plate?, directed by Catherine Gund, daughter Sadie Hope-Gund & her friend Safiyah Riddle, follows the 11-year olds as they learn about the politics of food and its various impacts on urban sustainability, among other things. I should add that this film is also alot of fun. It will be screening for FREE in Fort Greene Park Saturday June 27th at 9pm, and screening again Tues July 2nd at 6pm as part of BAM’s Afro-Punk Film Fest.

Hope this finds everyone well -

cheers

Jeremiah

- Nina Paley sends the following message:

Dear friend of “Sita Sings the Blues,”

Dear friend of “Sita Sings the Blues,”

The Sita Sings the Blues Merchandise Empire is finally live and open

for business: http://www.sitasingstheblues.com/store

(redirects to http://questioncopyright.com/sita.html )

At last we have DVDs and T-shirts for sale. Thanks for your support –

I won’t spam you again!

Love,

–Nina

From Patrick Smith:

“ANIMATION FROM HELL!”

“ANIMATION FROM HELL!”I’m curating a program for MOCCA Arts Festival this year called “Animation From HELL.” It’s a program of dark and twisted animation that will scare the fluffy bunnies out of any animation fan. This collection of disturbing shorts, past and present, has been hand picked by Satan himself.

Sunday, June 7, 2009

5:00pm – 6:00pm

at the Armory

68 Lexington Avenue, between 25th and 26th Streets

New York, NY

Frame Grabs &Independent Animation 05 Jun 2009 07:28 am

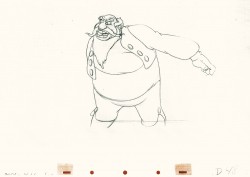

Bruno’s Allegro 2

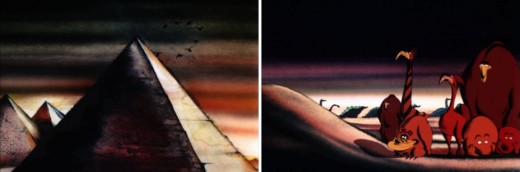

- Ravel’s “Bolero” continues in Allegro Non Troppo, and Bruno Bozzetto‘s extraordinary musical sequence moves on. Prior to seeing this film for the first time, I knew Bozzetto’s work well. I had seen many of his shorts and was a big fan. He never failed to have a big comment on society while making incredibly funny films. They were extraordinarily rich gems.

- Ravel’s “Bolero” continues in Allegro Non Troppo, and Bruno Bozzetto‘s extraordinary musical sequence moves on. Prior to seeing this film for the first time, I knew Bozzetto’s work well. I had seen many of his shorts and was a big fan. He never failed to have a big comment on society while making incredibly funny films. They were extraordinarily rich gems.

This film, however, was a surprise. The writing, as usual, was brilliant. The animation was more fluid, the styles were more varied and the calibre of each piece was very high. Of course, I should have expected masterful work from a master. It still holds up well on the little TV screen – and I’m sure it’s as strong in a theater (having seen it projected no too long ago.)

Here are the remainder of the frame grabs for that sequence.

52

52(Click any image to enlarge.)

return to live action