Category ArchiveJohn Canemaker

Independent Animation &John Canemaker &repeated posts &Richard Williams &SpornFilms &Theater 15 Jan 2012 06:02 am

Photo recap – Woman of the Year

Recently, I found myself talking about my work on this show. It made me go back in search of this post from January 2007, and I thought I’d recap today. Hope you don’t mind.

Woman of the Year was a project that came to me in the second year of my studio’s life – 1981. Tony Walton, the enormously talented and fine designer, had gone to Richard Williams in search of a potential animator for WOTY (as we got to call the name of the show.) Dick recommended me. But before doing WOTY, there were some title segments needed for Prince of the City, a Sidney Lumet film. (I’ll discuss that film work some other day.)

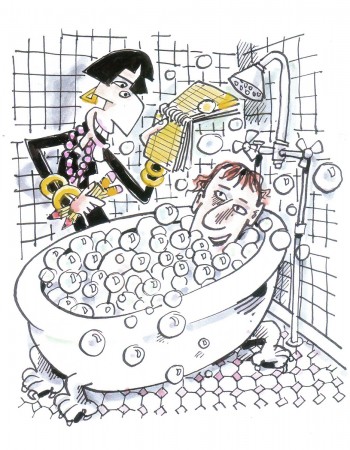

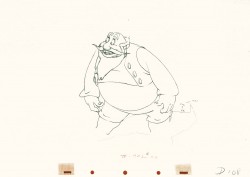

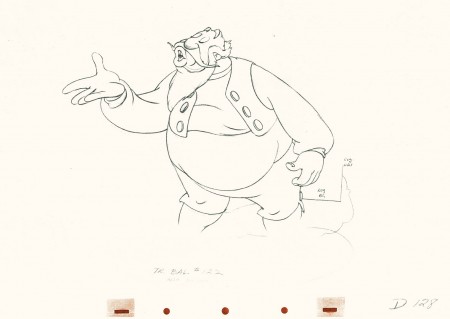

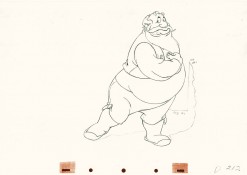

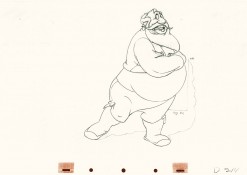

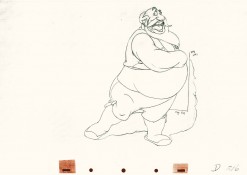

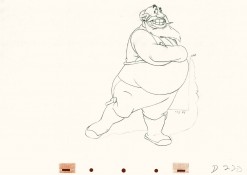

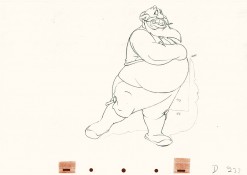

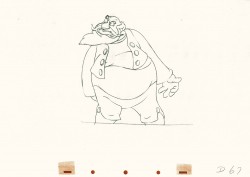

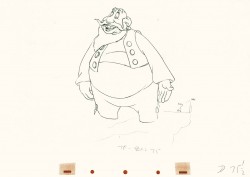

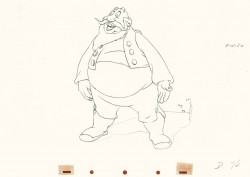

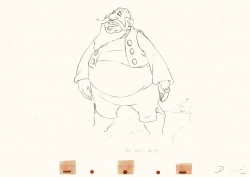

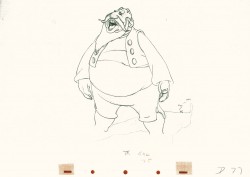

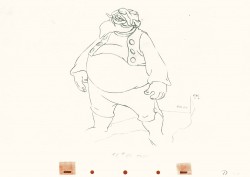

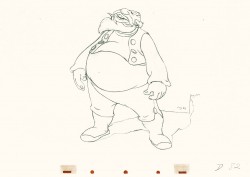

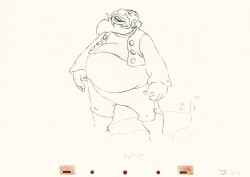

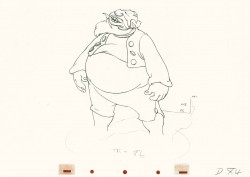

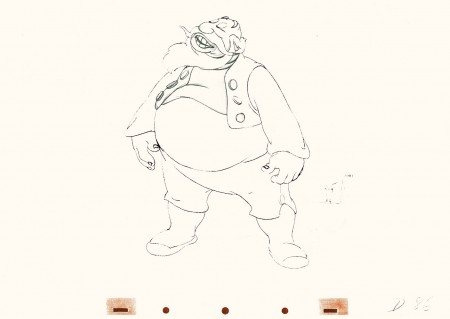

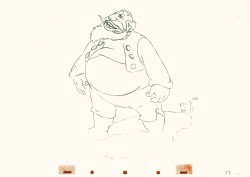

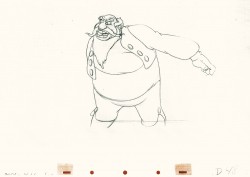

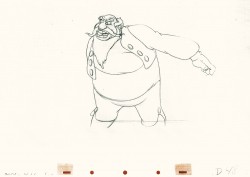

Tony Walton designed the character, Katz, which would be the alter-ego of the show’s cartoonist hero, played by Harry Guardino. Through Katz, we’d learn about the problems of a relationship with a media star, played by Lauren Bacall.

.

It turned out to be a very intense production. Three minutes of animation turned into twelve as each segment was more successful than the last. There was no time for pencil tests. I had to run to Boston, where the show was in try-outs, to project different segments weekly;  these went into the show that night – usually Wednesdays. I’d rush to the lab to get the dailies, speed to the editor, Sy Fried, to synch them up to a click track that was pre-recorded, then race to the airport to fly to the show for my first screening. Any animation blips would have to be corrected on Thursdays.

these went into the show that night – usually Wednesdays. I’d rush to the lab to get the dailies, speed to the editor, Sy Fried, to synch them up to a click track that was pre-recorded, then race to the airport to fly to the show for my first screening. Any animation blips would have to be corrected on Thursdays.

There was a small crew working out of a tiny east 32nd Street apartment. This was Dick Williams’

apartment in NY. He was rarely here, _______(All images enlarge by clicking.)

and when he did stay in NY, he didn’t

stay at the apartment. He asked me to use it as my studio and to make sure the rent was paid on time and the mail was collected. Since we had to work crazy hours, it was a surprise one Saturday morning to find that I’d awakened elderly Jazz great, Max Kaminsky, who Dick had also loaned the apartment. Embarrassed, I ultimately moved to a larger studio – my own – shortly thereafter.

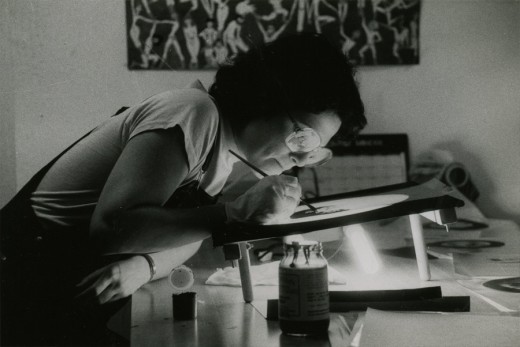

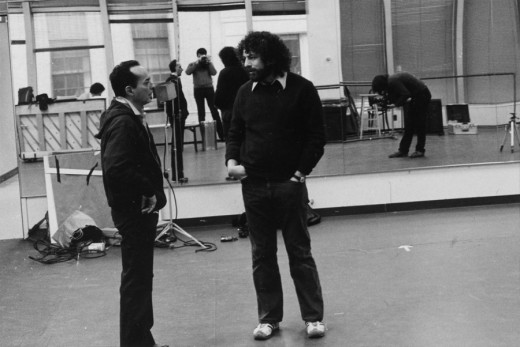

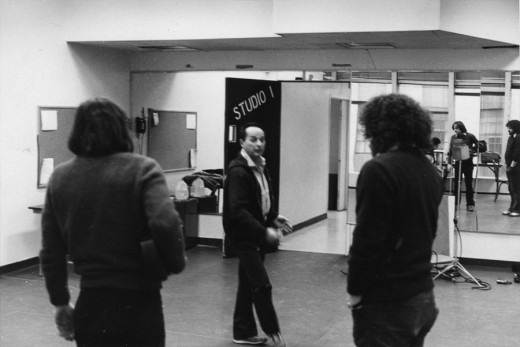

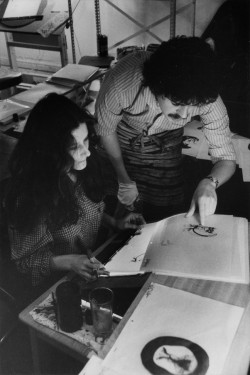

Here are a couple of photos of some of us working:

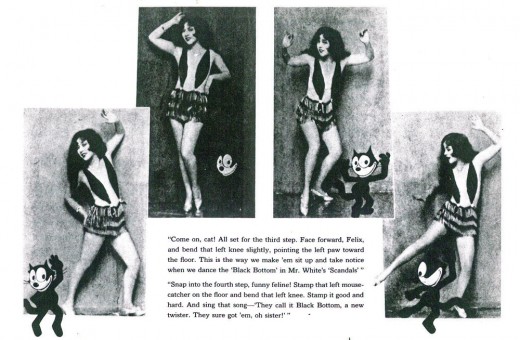

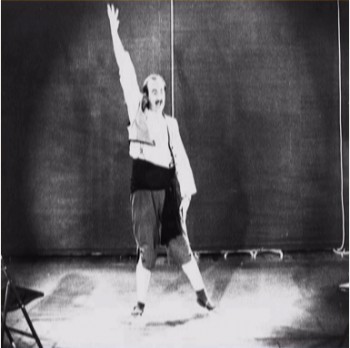

Tony Charmoli was the show’s choreographer. He worked with me in plotting out the big dance number – a duet between Harry Guardino and our cartoon character. I think this is the only time on Broadway that a cartoon character spoke and sang with a live actor on stage. John Canemaker is taking this photograph and Phillip Schopper is setting up the 16mm camera.

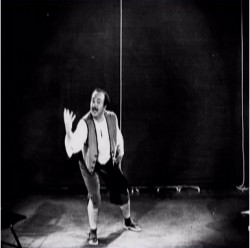

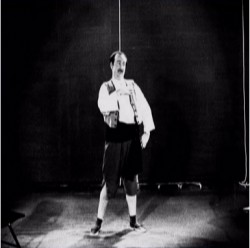

Here Tony Charmoli shows us how to do a dance step. Phillip Schopper, who is filming Tony, figures out how to set up his camera. We used Tony’s dancing as reference, but our animation moves were too broad for anyone to have thought they might have been rotoscoped.

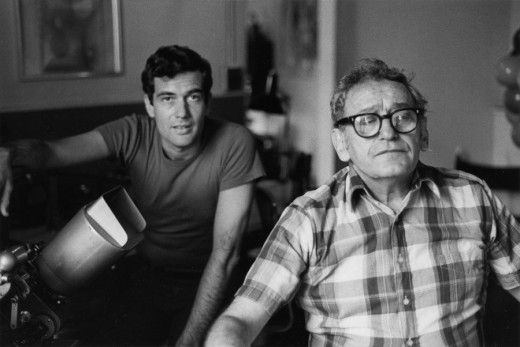

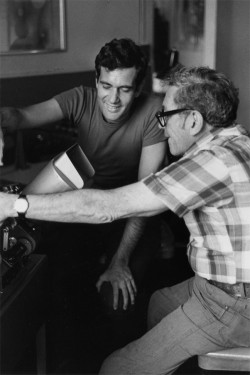

John Canemaker is working with Sy Fried, our editor. John did principal animation with me on the big number. Here they’re working with the click track and the live footage of Tony Charmoli to plot out the moves.

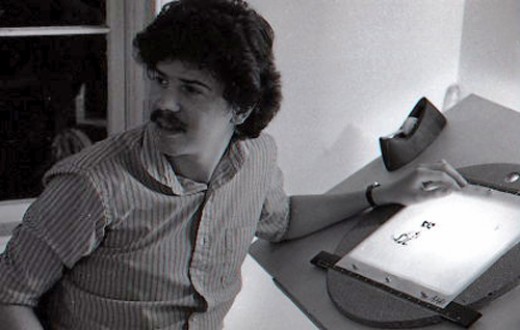

Steve Parton supervised the ink and paint. To get the sharpest lines, we inked on cels and didn’t color the drawings. It was B&W with a bright red bowtie. A spotlight matte over the character, bottom-lit on camera by Gary Becker.

5

5  6

6

5. Steve Parton works with painter Barbara Samuels

6. Joey Epstein paints with fire in her eyes.

8

8 9

9

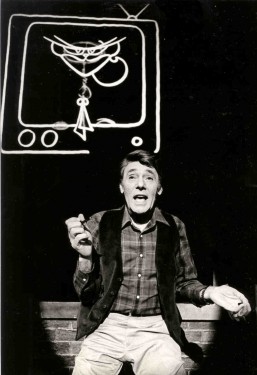

8. Harry Guardino on stage with the creation of “Tessie Kat” developing on screen behind him. This was Harry’s first big solo.

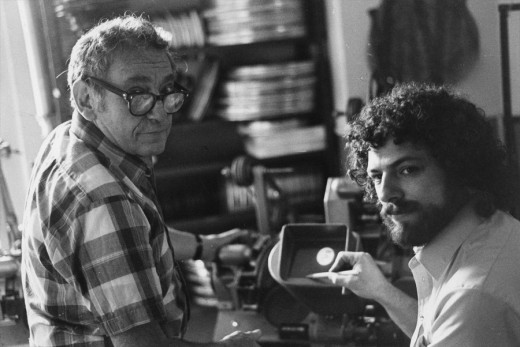

9. John Canemaker gets to see some of his animation with Sy Fried, editor.

One of my quick stops from the lab on the way to Boston? No, I think this is a posed photo.

Art Art &Books &Comic Art &Illustration &John Canemaker &T.Hachtman 03 Dec 2011 07:45 am

Paul & Sandra and John and Tom and Bill

- This past Thursday night, Paul and Sandra Fierlinger presented an hour’s worth of their latest project at Parson’s School. The film, Slocum at Sea with Himself, tells the story of the first person to have sailed SOLO around the world.

- This past Thursday night, Paul and Sandra Fierlinger presented an hour’s worth of their latest project at Parson’s School. The film, Slocum at Sea with Himself, tells the story of the first person to have sailed SOLO around the world.

The film was a work in progress in every sense of the phrase. It started in full color, included scenes over final Bgs that weren’t colored and had other scenes that were pure pencil test. The sound was predominantly music composed and performed by the brilliant Shay Lynch. (You may know his music from the many films he did for Jeff Scher.) Yet, it all stood with a great dignity as a strong piece.

The film was full of potential to be even greater than their last feature, My Dog Tulip. Imagery was stunning and beautifully designed and animated (as usual from this team). It was a real treat seeing the work in progress, and it was easy to fill in the gaps. The movie takes place almost completely on water, and it’s amazing the effects they’ve achieved in animating such a difficult project. I was wholly taken by it.

As monumental as the screening was – truly inspirational, the talk Paul gave in advance was thought provoking. They are making the film with their own money and planning to release it online in short segments. All told the feed would take about six months to receive the entire feature. To buy these feeds, which will be built into a website that would constantly change for each segment, will cost about $30 in total. They’re hoping for a built-in audience of boaters and leisure craft enthusiasts around the world. Slocum is a well-known story to these folk, and the likelihood that they’d have interest in the subject is great.

Theirs is a provocative idea for distributing the film, and the business model Paul presented seemed original and probably a successful one. It will take some time before the feature is finished, but I’ll be watching closely to see how successful they’ll be. I’d bet on them, too.

There is no doubt of the love they’re pouring into this project. Take a look at these stills:

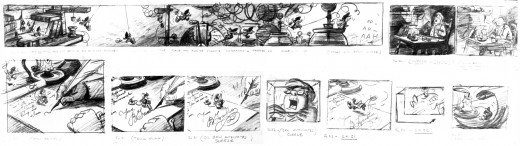

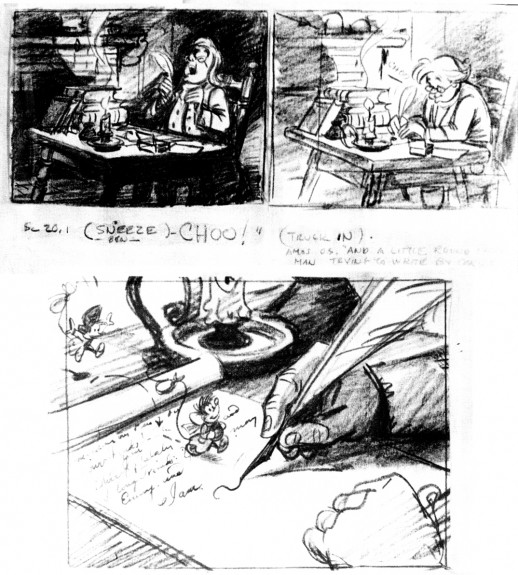

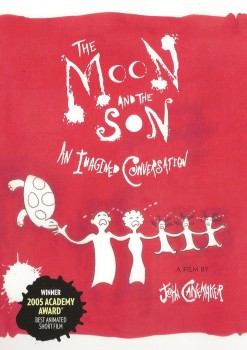

- The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, John Canemaker’s animated short, is now available in a special edition DVD. This powerful and moving film, which has won both the Academy Award and the Emmy Award, explores the difficult emotional terrain of father/son relationships as seen through Canemaker’s own turbulent relationship with his father.

The Moon and the Son combines many different elements from John’s remembered versions of the facts, to the actual evidence of the life on screen: the trial transcripts, audio recordings, home movies, and photos. The original and stylized animation tells the true story of an Italian immigrant’s troubled life and the consequences of his actions on his family. The film features the voices of noted actors Eli Wallach and John Turturro in the roles of father and son.

The DVD includes the complete 28-minute film and the following bonus materials:

- A new documentary detailing the film’s creative evolution, influences and reception, with animation director/designer John Canemaker and producer Peggy Stern.

- The first rough cut (working title: “Confessions of my Fatherâ€) with original soundtrack

- A Photo gallery of production sketches, preliminary artwork and storyboards

I enjoyed thumbing through all the extras on this DVD. When the film was being made, John shared its progress with me at several stages. I’m intrigued with how much material was there in the development. As a long time friend with John, I felt I’d known some of the story over the years. But the film, and now the new material, give me larger insight to the full story. Spending time reading the storyboard (one of the extras) again – having seen the film several times – allowed me to see some of the background which shaped John’s quest to tell this story.

The DVD is available now on Amazon.

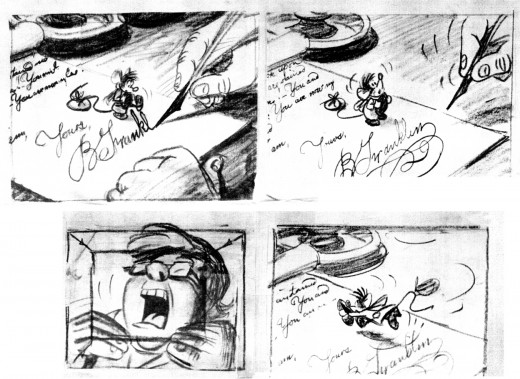

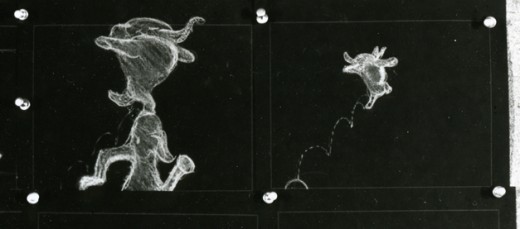

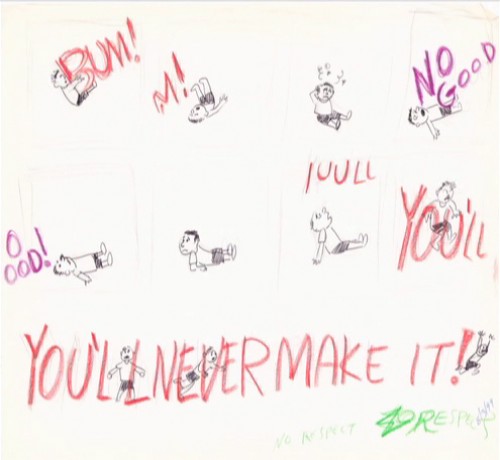

A somewhat Feiffer-like page within the storyboard.

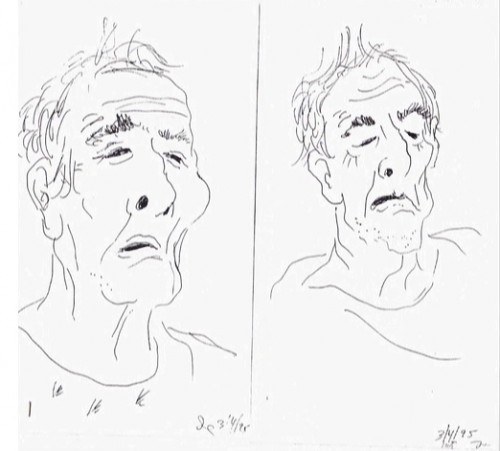

A very “Canemaker” sketch that reminds me a bit of a Picasso sketch.

There’s lots more on the DVD.

____________________________________

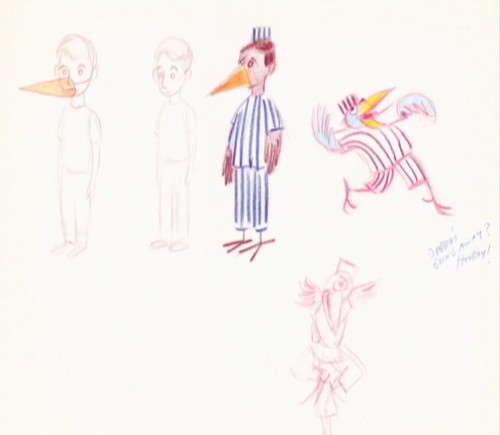

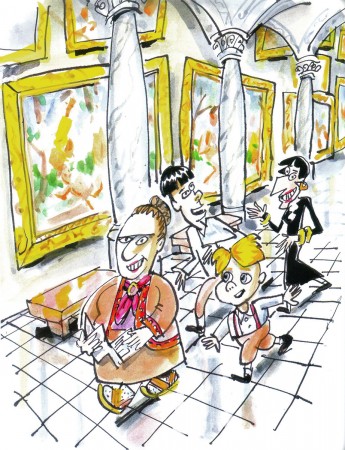

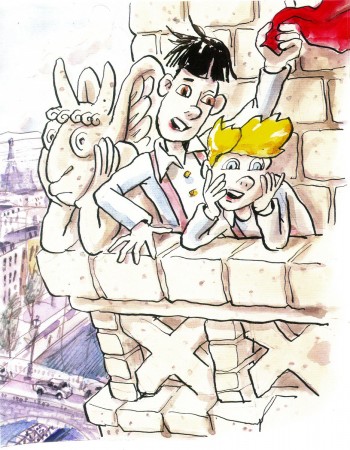

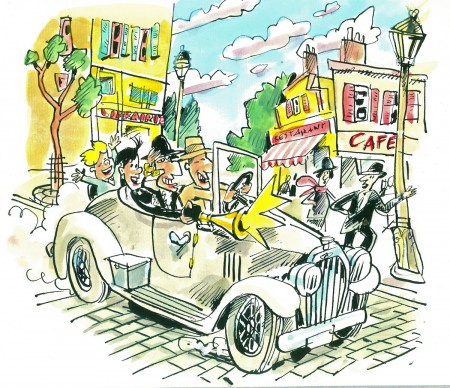

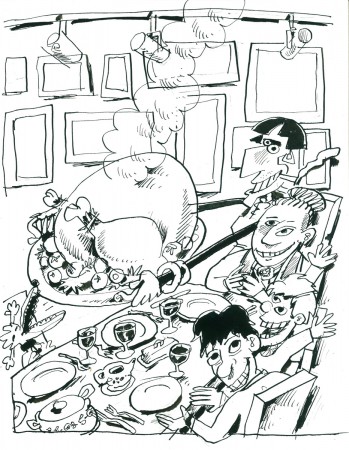

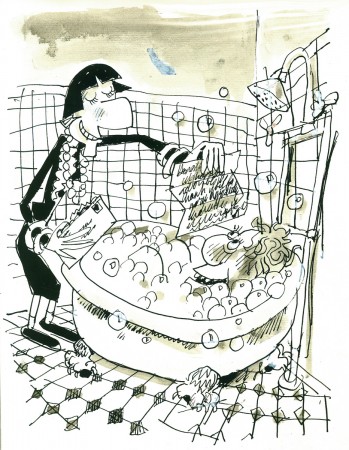

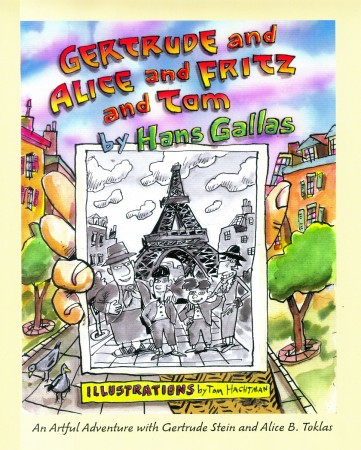

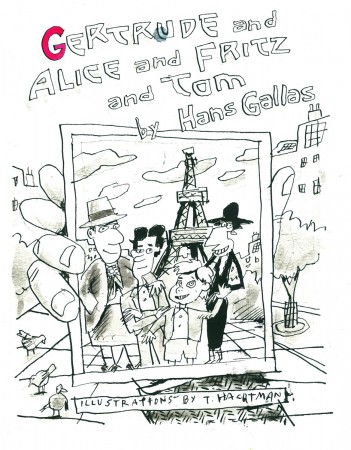

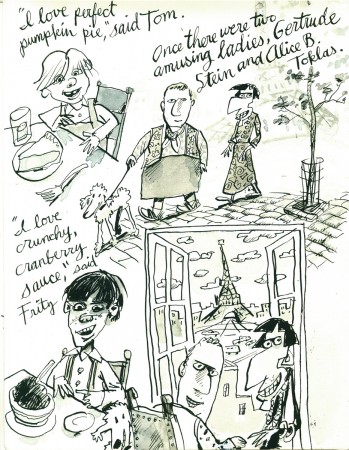

- Tom Hachtman has seen an unusual turn with his Gertrude and Alice characters. You’ll remember that he’d developed a comic strip, Gertrude’s Follies, built around Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. A friend and admirer of the strip, Hans Gallas, has written a children’s book around Tom’s characters, and Tom illustrated the book. Now that book’s been published, and can be purchased from their site. Gertrude and Alice and Fritz and Tom is a charming account of what happens when Gertrude and Alice have to take care of a couple of young boys during their stay in Paris.

Here are some of the book’s exuberant illustrations.

The book’s cover

And here are some of Tom’s original sketches for the book.

Original sketch for the cover.

Très different from the final.

A preliminary sketch for a lot of pages

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

- Bill Benzon, on his blog New Savannah, has finally completed his treatise on Fantasia and has published it in a PDF form. You can download this here for a great read. 96 pages of intelligent discourse on the feature. This document contains his original, and shorter commentary on the Pastoral sequence. For his longer take on that sequence download this document.

Animation Artifacts &Disney &John Canemaker &Peet &repeated posts &Story & Storyboards 28 Nov 2011 07:45 am

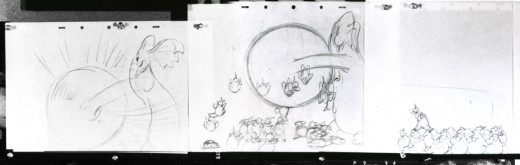

Ben and Me Board – repost

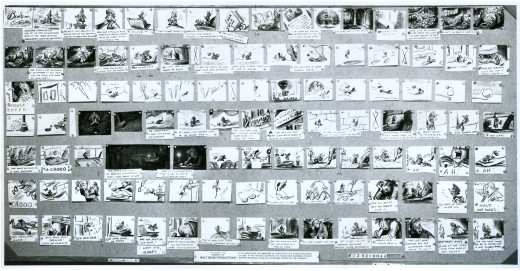

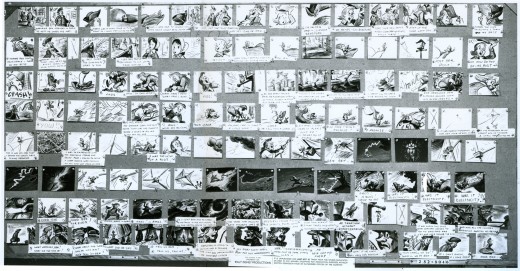

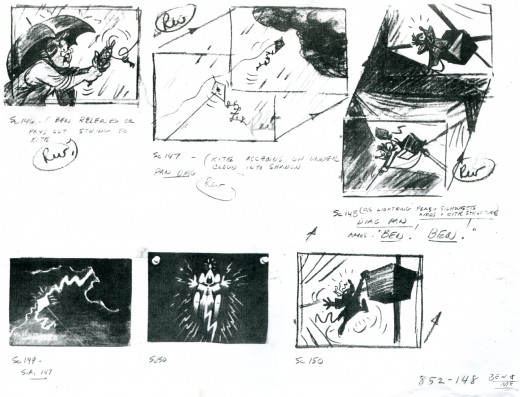

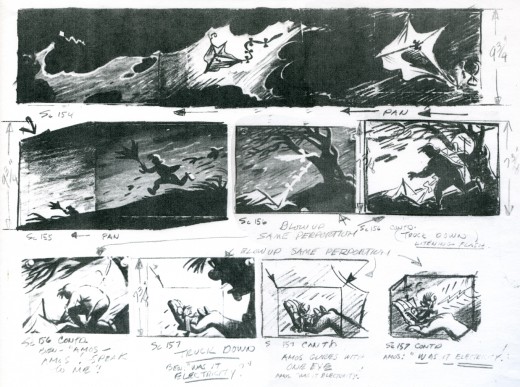

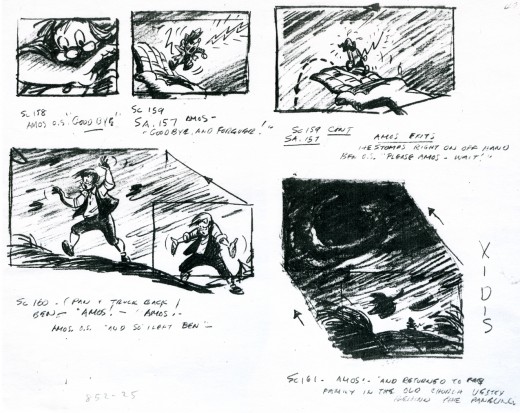

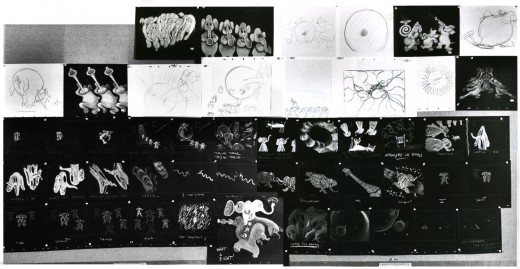

- Bill Peet was one of the prime artists who shaped many of the Disney features. He has been an enormous influence on me and thanks to John Canemaker, who has loaned me the following storyboard, I’m pleased to post some of Mr. Peet’s excellent artwork.

- Bill Peet was one of the prime artists who shaped many of the Disney features. He has been an enormous influence on me and thanks to John Canemaker, who has loaned me the following storyboard, I’m pleased to post some of Mr. Peet’s excellent artwork.

Ben and Me was a 20 min short produced in 1953. It’s an oddity in the Disney canon. The story of a mouse who influences Benjamin Franklin through many of his most famous moments was originally a book by Robert Lawson and was adapted by Bill Peet for the studio.

The photostats of the storyboard, like others I’ve posted, is extremely long. Hence, I’m posting them as large as I possibly can so that you’ll be able to read them once you’ve enlarged the images.

These three panels are followed by a couple more revisions. The revisions I only have as xeroxes – lesser quality.

This image is a recreation of the extraordinary pan as seen in the first row of the storyboard posted above. It’ll enlarge to a size where you can properly see it. A couple of the objects were on secondary overlays creating a minimal multiplane effect.

Bill Peet offered great drawings in his storyboards, and I’m sure he brought a lot of inspiration to the animators.

This is an excedingly long pan (30 inches), and is almost invisible in this minimal thumbnail. Rather than break it up into shorter bits, I’m posting it as is and hope it won’t be too much of a problem for you to follow in its enlarged state. You have to click on it to see it.

The image below is a recreation of this pan from the final film done using multiple frame grabs.

There’s an excellent article about the making of Ben and Me by Wade Sampson at Jim Hill Media. It gives quite a bit of information about this odd short and is well worth reading as a companion to these boards.

Animation Artifacts &John Canemaker &repeated posts 24 Oct 2011 06:51 am

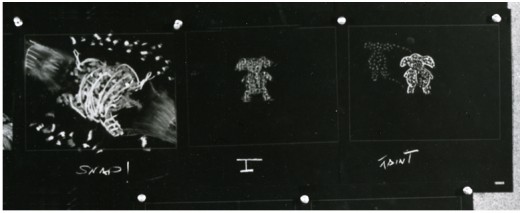

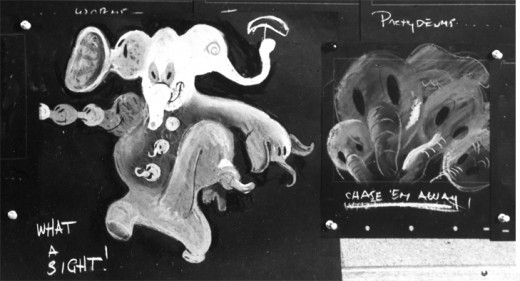

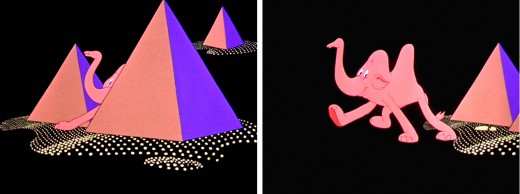

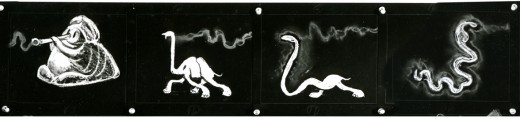

Pink Elephant Recap

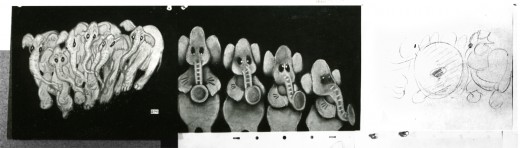

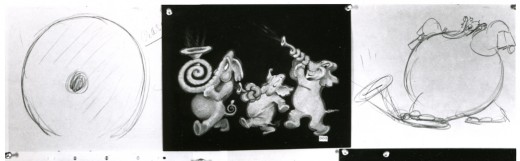

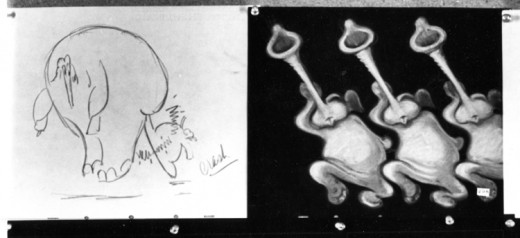

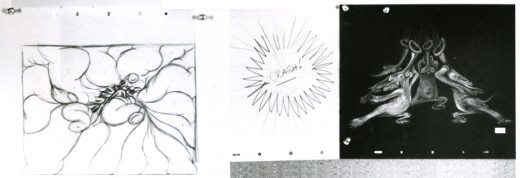

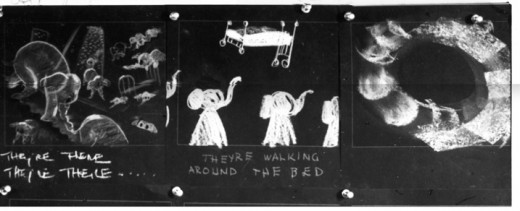

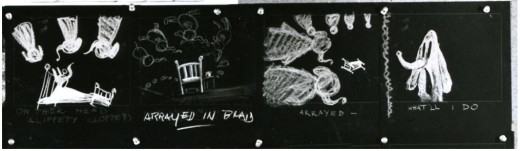

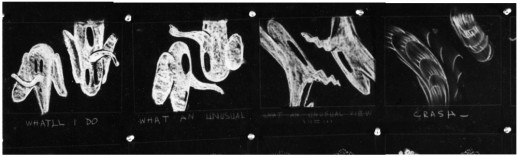

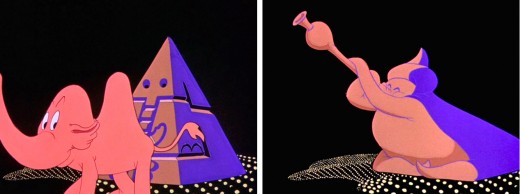

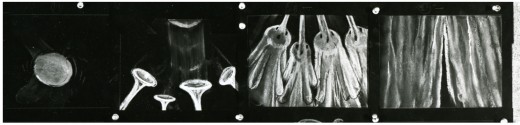

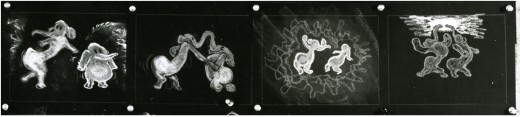

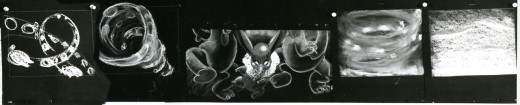

- Recently, I saw a small part of Aladdin on television. A large part of the Genie’s song reminded me of Pink Elephants from Dumbo. I thought, then, that I should post anew the models/sketches and drawings from that sequence. It originally was broken in two parts when it saw daylight here in 2007. I’ve combined the two posts into one.

Once again, thanks to John Canemaker, I have several photo images to display. Some frame grabs accompany the piece.

These are rather small images, so by cutting up the large boards and reassembling them I can post them at a higher resolution, making them better seen when clicking each image.

I’ve interspersed some frame grabs from the sequence to give an idea of the coloring.

The following images were in the gallery part of the dvd. These are the color versions of some of the images above.

Books &John Canemaker 13 Oct 2011 05:50 am

Canemaker’s Felix Book

- I’ve recently been rereading the classics. No, I don’t mean Madame Bovary or Great Expectations; I mean animation’s classic books. Since this blog came into being a mere 6 years ago, I haven’t had the chance to review many of these books, which predate this blog, and I thought it time to share my guilty pleasure (reading) with you. So, I’m about to start reviewing some older books. In a sense, I’ve already done this by commenting on some of the books I never got up to reading – such as Culhane’s Talking Animals and Other People. I’m also going to review some books I’ve been rereading.

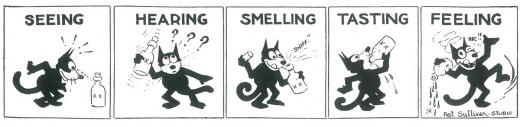

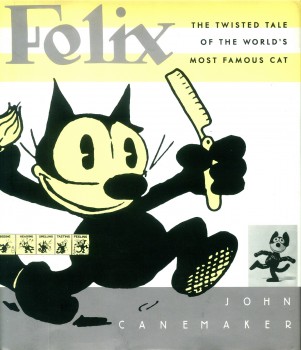

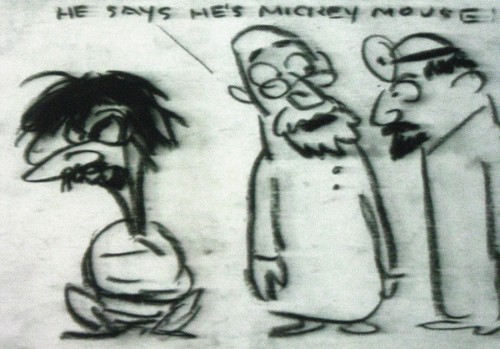

First up is Felix, The Twisted Tale of the World’s Most Famous Cat by John Canemaker. This was Canemaker’s second book, following his Winsor McCay, His Life & Art. This is the second time through this book for me (lately I’ve been into reading about the earliest days of animation’s history), and it’s every bit as entertaining and informative as my first read.

First up is Felix, The Twisted Tale of the World’s Most Famous Cat by John Canemaker. This was Canemaker’s second book, following his Winsor McCay, His Life & Art. This is the second time through this book for me (lately I’ve been into reading about the earliest days of animation’s history), and it’s every bit as entertaining and informative as my first read.

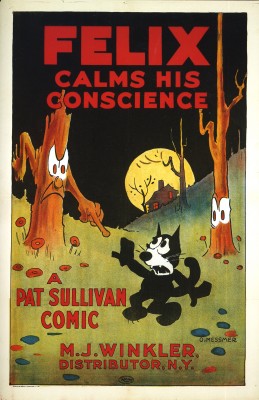

You get both a history of Pat Sullivan, the entrepreneur who made a success of Felix and Otto Messmer, the animator who actually developed and brought Felix to life. The two stories run concurrently, and it’s obvious that Sullivan’s life was more dramatic. His story is a potboiler.

At the very start of his studio, Sullivan was incarcerated for nine months after being convicted of raping a 14 year old girl. Then he watches Messmer develop Felix into a superstar, capable of competing with any live-action celebrity. Riches flowed into the studio most of which ended up in Sullivan’s pockets.

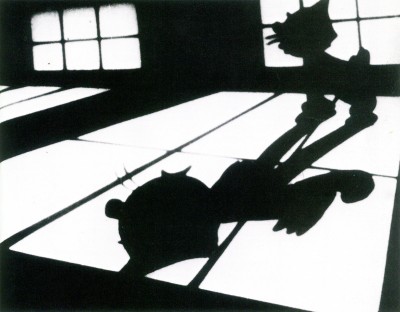

Still from “Sure Locked Homes”

At the end of his life, when Felix films were on a decline, Sullivan’s wife had committed suicide (although her falling out a window to her death may have been accidental), and Sullivan’s health began to quickly deteriorate. “Whether caused by grief over Marjorie’s death, years of alcoholic abuse, or the tertiary stage of syphilis that finally affects the brain, or a combination of all three, it was obvious that Pat Sullivan was losing his mind.”

This is a page turner of a story.

.

Threaded through it all is the steady and less interesting read of the shy animator who worked tirelessly to create, develop and produce the first character to exhibit a screen personality. Otto Messmer was the synthesis of most animators: work hard during the day in a mostly internal job, then go home to the mundane, middle class existence in the suburbs. It doesn’t make for a great read, but it made for great films.

Threaded through it all is the steady and less interesting read of the shy animator who worked tirelessly to create, develop and produce the first character to exhibit a screen personality. Otto Messmer was the synthesis of most animators: work hard during the day in a mostly internal job, then go home to the mundane, middle class existence in the suburbs. It doesn’t make for a great read, but it made for great films.

Canemaker tells both well, and it does have its effect. The book moves quickly and enjoyably.

It’s also something of a scrapbook in that there are plenty of images of Felix to show you what a complicated character Messmer had created. These cartoons were certainly more for adults than children. There was plenty of alcohol in the films and strips that flowed from the studio. War was a subject that was treated seriously. World War I had acutely affected many of the animators as well as the audience, and these films were particularly successful in the series.

For ten years the films reached a zenith of riches, and it was difficult for other animated films to break through the inner circle that Felix had developed. Margaret Winkler and her husband, Charles Mintz, distributed the Felix films, and when Sullivan sought greater fees he threatened to quit. Winkler then developed the young Walt Disney to serve as a backup plan should she lose the Felix films. She eventually did. Her husband ultimately forced Disney out as well, and that’s when the historic happened.

Disney created Mickey Mouse in his first sound film, Steamboat Willie. All of Sullivan’s tardy attempts to issue post-recorded versions of Felix with sound were useless, and Felix became a has been. Sullivan died within four years, and Otto Messmer quietly spent the rest of his life hiding behind the Felix the Cat comic strips. It’s a sad story that John Canemaker reveals, and he gives the full version in this attractive book.

Disney created Mickey Mouse in his first sound film, Steamboat Willie. All of Sullivan’s tardy attempts to issue post-recorded versions of Felix with sound were useless, and Felix became a has been. Sullivan died within four years, and Otto Messmer quietly spent the rest of his life hiding behind the Felix the Cat comic strips. It’s a sad story that John Canemaker reveals, and he gives the full version in this attractive book.

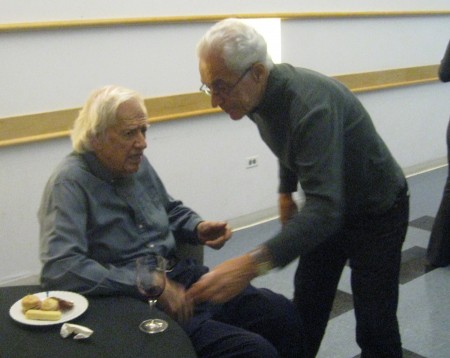

I remember way back when, I think it was 1975, that I accompanied John Canemaker on a trip to Otto Messmer’s house and got to meet the man. The afternoon was quite pleasant, and I sat as an observer witnessing a casual and enjoyable Q&A with Mr. Messmer. I don’t remember much about the interview, but I do remember it as sunny and quite agreeable. I also remember my first reading of this book and seeing how John had turned that interview into something meatier than I remembered witnessing. He certainly interviewed Messmer many more times for the book (and the valuable documentary Otto Messmer and Felix the Cat, that he made in 1977.) It was my first time to see the fruit turned into facts, and it was an eye-opening experience.

Today I see the very informative book, and I also see the stylistic prose John adapted in the writing. It’s obvious he was completely invested in the subject and period and people of this book, and you can’t ask for much more from such an historic account. If this book isn’t part of your collection, it should be. At least, borrow it from the public library and read it.

Here‘s a nice interview from1991 with John and ira Gallen.

The documentary, Otto Messmer and Felix the Cat can be found on the DVD John Canemaker, Marching to a Different Toon.

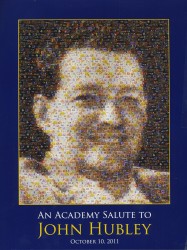

Commentary &Hubley &Independent Animation &John Canemaker 12 Oct 2011 06:51 am

A Hubley Affair

– The AMPAS program celebrating the early work of John Hubley went off wonderfully on Monday evening. The show started at 7pm, but prior to it there was a cocktail party for about 50 people. I have no idea who was invited to this, but it seemed to be Academy members who might have know the Hubleys as well as friends of the Hubley family. All four of the Hubley children were there including: Emily, her husband, Will Rosenthal, and their son, Max; Georgia and husband, Ira Kaplan (both part of the group Yo Lo Tengo); Ray Hubley, and Mark Hubley.

– The AMPAS program celebrating the early work of John Hubley went off wonderfully on Monday evening. The show started at 7pm, but prior to it there was a cocktail party for about 50 people. I have no idea who was invited to this, but it seemed to be Academy members who might have know the Hubleys as well as friends of the Hubley family. All four of the Hubley children were there including: Emily, her husband, Will Rosenthal, and their son, Max; Georgia and husband, Ira Kaplan (both part of the group Yo Lo Tengo); Ray Hubley, and Mark Hubley.

Also there, were Tissa David, Ed Smith, Candy Kugel, George Griffin, Vinnie Cafarelli, Lee Corey, Ruth Mane, John Canemaker (of course) with Joe Kennedy and others I probably have forgotten. Patrick Harrison and John Fahr ran and hosted the event for the Academy.

At the program I saw: Ray Kosarin, Linda Beck, Stephen MacQuignon, Richard O’Connor, Bill Plympton, and a hundred others that I recognized. The house was full.

As we entered the theater, prior to the start of the show, the soundtrack to Finian’s Rainbow was playing. Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Ella Logan and Barry Fitzgerald.

The actual program began as all Academy events do, exactly on time. Patrick Harrison spoke for two minutes promising that next month the event would be a retrospective of the work of Saul Bass done in conjunction with MOMA. He then introduced John Canemaker, and we were off and running.

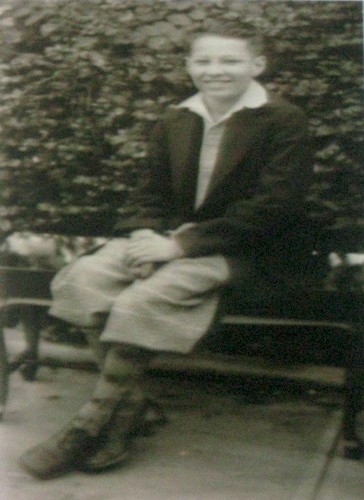

John started with a PowerPoint presentation that showed the child, John Hubley, his surly uncle who became the model for Mr. Magoo; we saw some childhood drawings as well as a number of strong influences including classmate, Alvin Lustig, who designed the UPA logo. These were followed by some of the artwork Hubley did for Disney, which included a lot of Layouts and preliminary Background sketches. We saw art done during the War as well as preliminary art for many of the UPA films. John Canemaker featured a lot of Hubley in-house cartoon drawings peppered throughout the presentation.

John started with a PowerPoint presentation that showed the child, John Hubley, his surly uncle who became the model for Mr. Magoo; we saw some childhood drawings as well as a number of strong influences including classmate, Alvin Lustig, who designed the UPA logo. These were followed by some of the artwork Hubley did for Disney, which included a lot of Layouts and preliminary Background sketches. We saw art done during the War as well as preliminary art for many of the UPA films. John Canemaker featured a lot of Hubley in-house cartoon drawings peppered throughout the presentation.

This talk ultimately led to screening the movies.

Unfortunately, it started with the only 16mm print, a soft-focus soft color print of Brotherhood of Man. Somewhere a good print of this film exists, and I don’t know when it’ll be found – hopefully in my lifetime. It’s such an enormously powerful film, designed in a style which was borrowed from Saul Steinberg‘s work at the time.

Flat Hatting followed with a beautiful 35mm print. This is a brilliantly directed film showing how much good can be done with limited animation. It never felt limited, nor does it feel like an educational film for pilots. It’s very entertaining and drew a lot of laughs. Hubley had spent years directing mediocre films under Frank Tashlin at Columbia and a number of films for the military. This film shows how much he had learned as a director in such a short time.

The Magic Fluke is probably the best of the Fox and Crow series. This film has a great sense of design featuring that famous background by Jules Engel of the concert hall. I’m not sure Hubley was best cast as the director of a lightning quick comedy cartoon, but, for the most part, it works well. The print, again, was sterling.

Following this was a beautiful print of Ragtime Bear, the first Magoo cartoon. I hadn’t remembered how fluid the animation was; there was some beautiful distortion on Magoo later in the film. My guess is that it was a Pat Mathews scene. The film offers all of Magoo’s traits, but the character design is far away from what Pete Burness ended up directing.

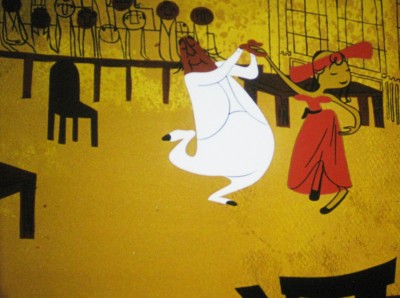

The cr̬me de la creme of the evening: Rooty Toot Toot followed. What a beautiful, big 35mm print. What a stunner of a scene Рthat great Grim Natwick animation of Nelly Bly Рall blue Рcorkscrewing her hands and arms in the witness chair. Beautiful and funny. This is certainly one of the great films ever created.

An image photographed off the screen

There were a stash of commercials – both West and East coast – from the original Storyboard Prods. I own prints of all screened except for my favorite: a spot for Mennen aftershave. A rectangle of wrinkles around a pair of eyes. Mennen helps the lines smooth out, and the commercial uses abstraction for a very funny commercial. It was the first time I’d seen this commercial. They certainly were creative back then. Hubley repeated the use of abstraction in a number of other, later spots. I’m thinking particularly of one done in the early 70s for AT&T; Tissa David animated.

Beautiful reconstructed prints from MOMA included Adventures of an * and Tender Game. One was more beautiful than the other. Both are great films.

Voyage to Next was represented with a beautiful print, though I have to say, I never really liked this film. I had a lot to do with the making of it, and it really was a challenge and a great learning experience. About a third of the way through the production money ran out, and we had a film to get out with a small but great staff. There was a lot of stylistic improvisation done to try tokeep on a vbery tight budget, while being artful. It was a tough time for the Hubleys, and they stayed true to the film at hand.

Finally, the evening ended with a beautiful animatic called Facade. These were storyboards filmed (with slates) for a William Walton and Edith Sitwell score. John Canemaker actually located and got the rights to a version with Edith Sitwell, herself, actually doing the narration. Miraculously, it all seemed well in sync. This piece was done in 1964 as a sample for PBS., though the film was never completed. A real find for Canemaker straight from the Hubley collection. A film not seen by the public (and it hasn’t made its way into animation history books, either.)

All in all the show was so invigorating that the Academy had a hard time getting rid of us. People stayed and chatted in the lobby. It was a great event.

John and Joe, Heidi and I went out for dinner so we could chat about the program. I had a blast all night; it was one of the finest animation events I’d attended in many years.

Here are pictures I took during the evening.

.

1

1

The cocktail party

1

1

LtoR: John Canemaker, Georgia Hubley, Emily Hubley, Will Rosenthal

2

2

LtoR: unknown, Patrick Harrison, Georgia Hubley, John Canemaker,

unknown in rear, Emily Hubley, Will Rosenthal

3

3

LtoR: me, John Canemaker, Patrick Harrison

4

4

LtoR: Emily Hubley, George Griffin, Vinnie Cafarelli,

Candy Kugel, John Canemaker

5

5

LtoR: Mark Hubley, Candy Kugel, Vinnie Cafarelli

6

6

LtoR: Ed Smith, Vinnie Cafarelli

7

7

LtoR: Vinnie Cafarelli, Tissa David, Lee Corey, Ed Smith

8

8

LtoR: Vinnie Cafarelli, Ruth Mane, Tissa David

Lee Corey (partially hidden), Ed Smith

9

9

at table LtoR: Ed Smith, Heidi Stallings, Vinnie Cafarelli,

Ruth Manne, Tissa David

in rear, standing with winde glass: George Griffin w/Jeff Scher and wife, Bonnie.

10

10

The three Hubley Oscars for (LtoR): Moonbird,

The Hole, The Tijuana Brass Double Feature.

11

11

Audience front row (RtoL):

John Canemaker, Joe Kennedy, my empty seat,

Heidi Stallings, Tissa David, Ruth Mane

2nd Row, over empty seat: Stephen MacQuignon

3rd row (RtoL): Ed Smith, Richard O’Connor

12

12

LtoR:Tissa David, Heidi Stallings, Joe Kennedy, John Canemaker

13

13

Patrick Harrison giving thanks and introducing John Canemaker.

14

14

John Canemaker giving PowerPoint presentation

The following images were photograped during the PowerPoint

presentation or during the films. Consequently, they often soft focus.

With apologies.

.

15

15A very young John Hubley

16

16

An early John Hubley painting

17

17

A gag cartoon from Hubley. Self portrait in straight-jacket.

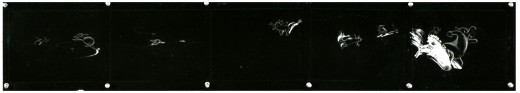

Images from Facade follow:

1

1

The animatic was done in 1964.

2

2

Stylistically it feels like:

Moonbird, The Hole and The Hat crushed into one.

5

5

The Hat for this animated duck-like character

Toward the end of the film there was one extremely long vertical pan.

It was an oil painting done by John, beautiful in its simplicity, perfectly

planned to fill a good 45 secs to a minute of screen time and yet it

was so compositionally correct and glosiously layed out.

All I can say is that I am so pleased to have had the opportunity to have

worked with John & Faith Hubley; it was all that it could have been and more.

One of the high spots of my life.

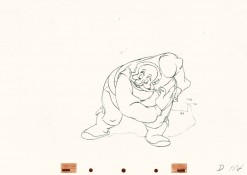

Animation &Animation Artifacts &John Canemaker 03 Aug 2011 05:36 am

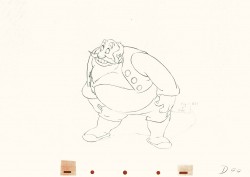

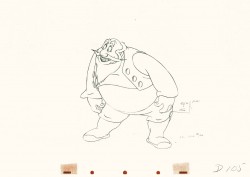

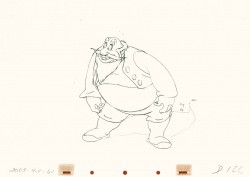

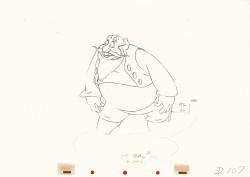

Tytla Devil Recaps

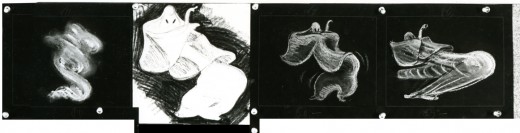

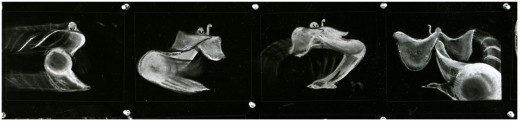

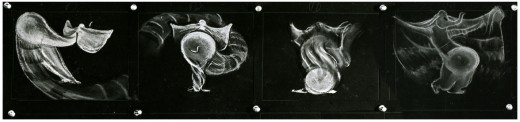

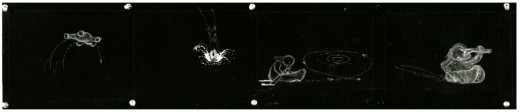

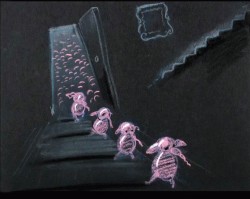

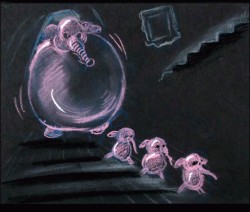

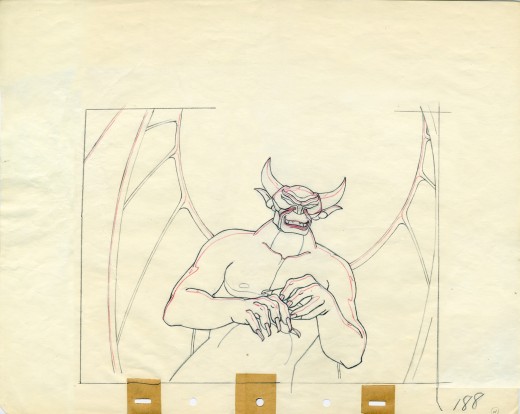

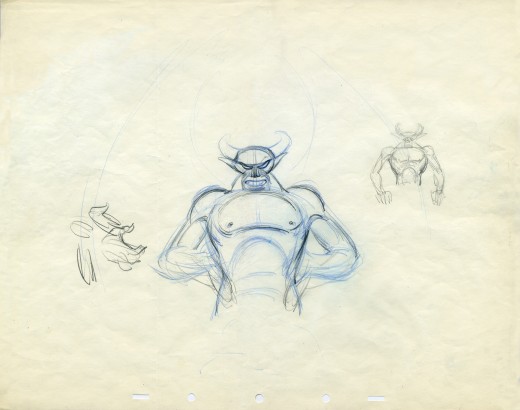

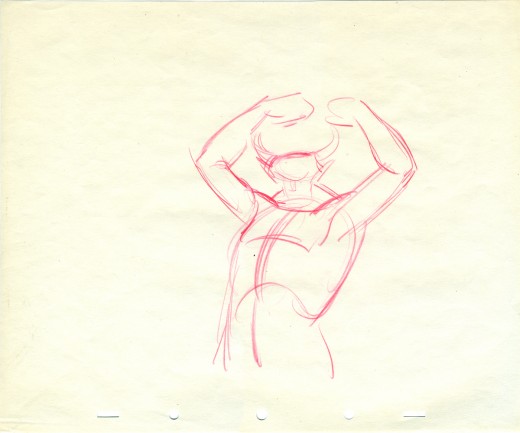

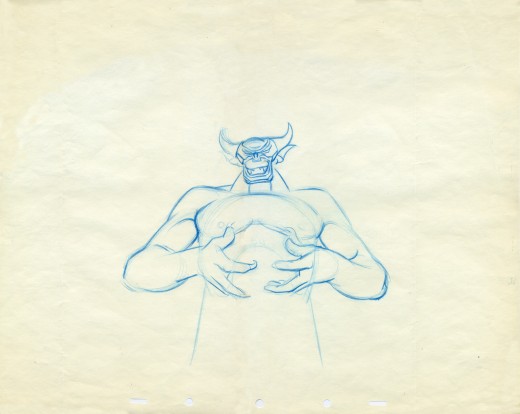

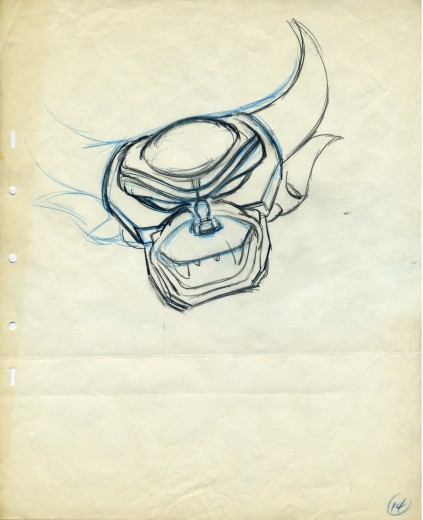

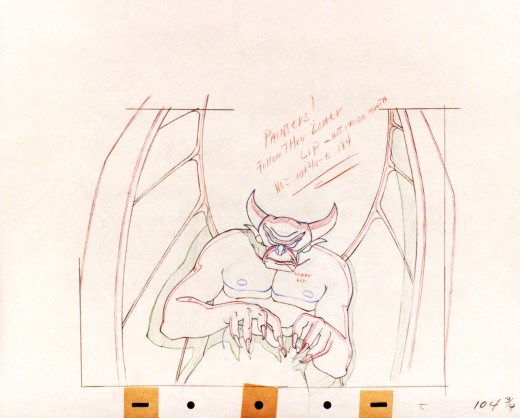

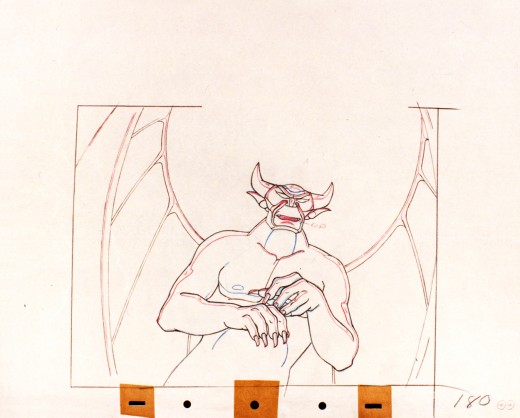

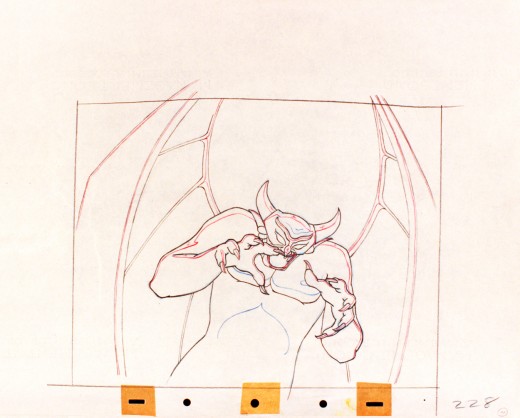

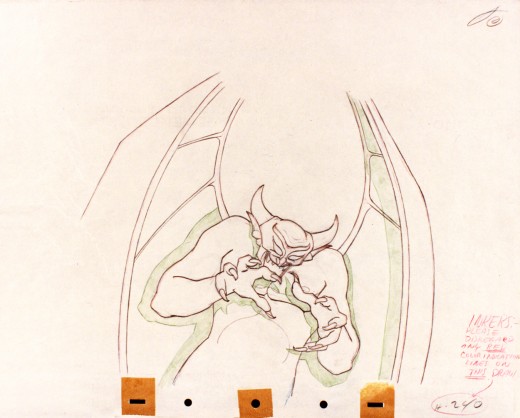

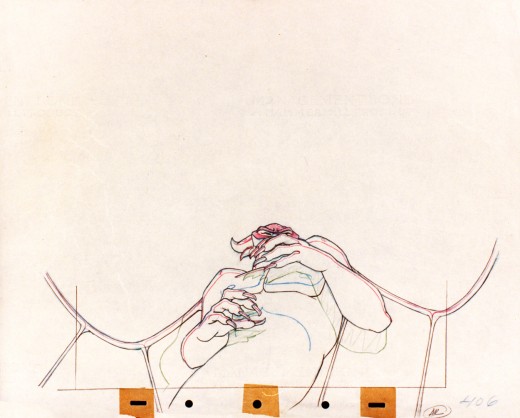

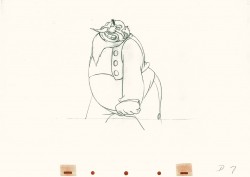

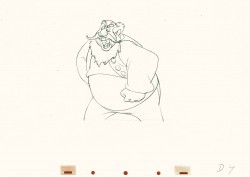

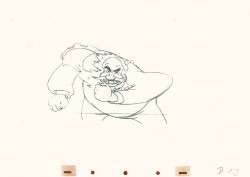

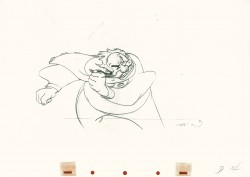

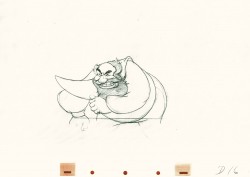

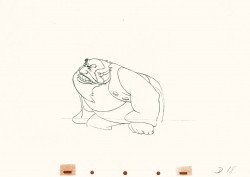

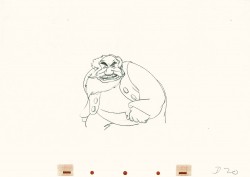

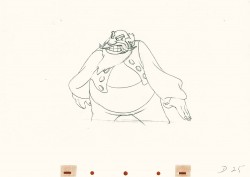

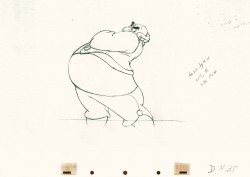

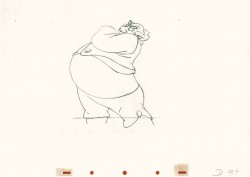

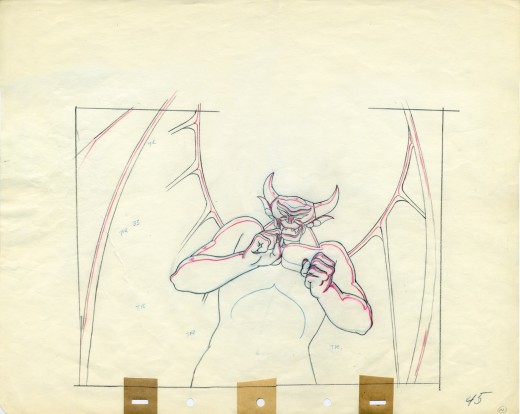

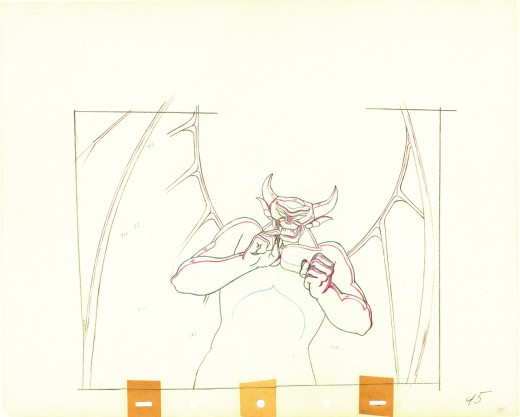

Continuing with my recaps of Bill Tytla’s Disney animation, I’ve put together a couple of past posts to show you some of the beautiful drawing Tytla did on Fantasia‘s Night On Bald Mountain sequence.

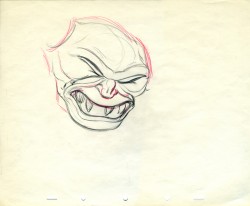

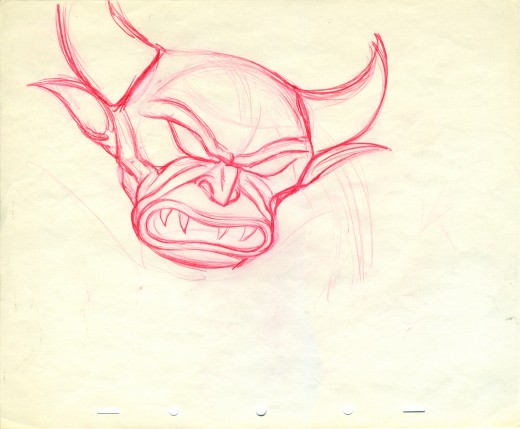

- Here’s what for me was a real treat to scan and post. I had some limited access to actual drawings by Bill Tytla of the Devil from Fantasia. The drawings are mostly roughs by Tytla, and they give a good sample of what his actual work looked like.

I don’t need to write about it; let me just give you these mages.

A good example of a Tytla drawing.

Here’s the clean up of the same drawing.

Animation roughs don’t get any more beautiful than this.

Art. What else need be said?

The individual drawings are stunning, and they’re

in service to a brilliantly acted sequence.

It will never get better.

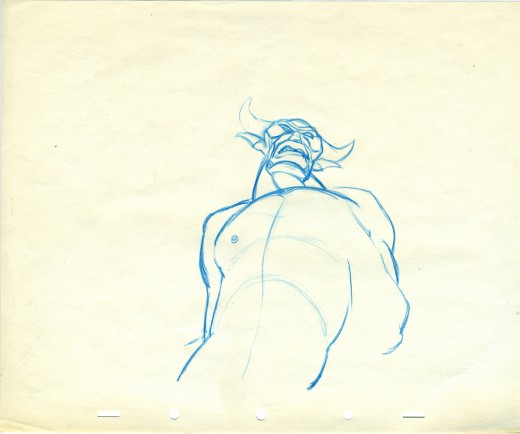

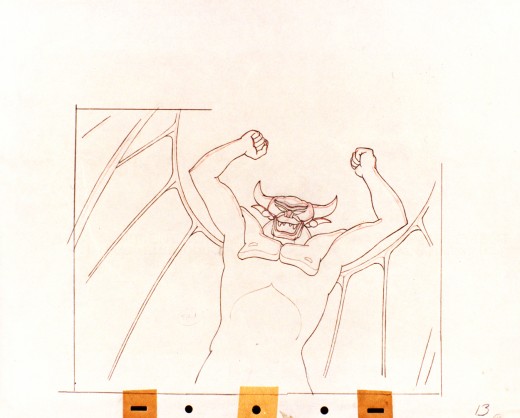

- Going under the assumption that there never are enough of Tytla’s Devils on the internet, I’ve got a few drawings to show here.

- Going under the assumption that there never are enough of Tytla’s Devils on the internet, I’ve got a few drawings to show here.

These were photographs of drawings taken (rather dark exposure that I lightened a bit) of what appears to be some cleanups. Most of them are from one scene; one drawing is from another. They’re all treasures.

How do you go from delicate Dumbo’s bath to this? That’s acting!

(Click any image to enlarge.)

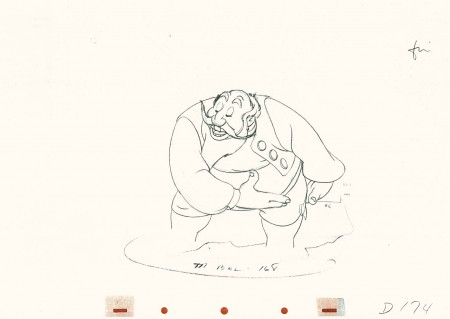

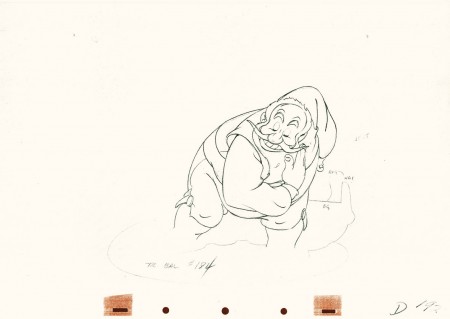

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &John Canemaker &Tytla 21 Jul 2011 06:30 am

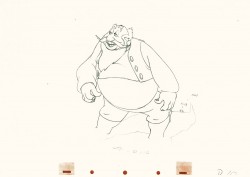

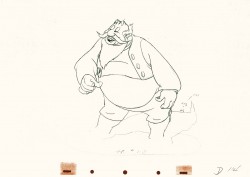

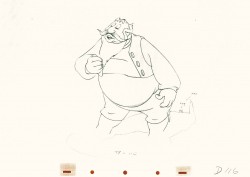

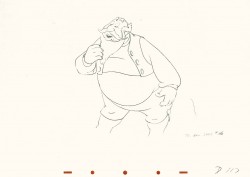

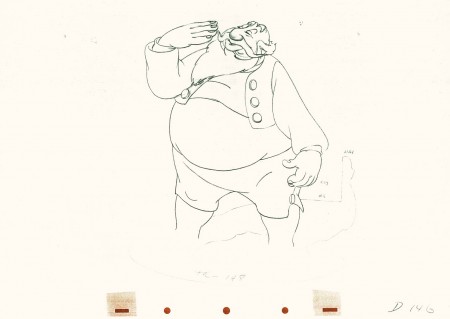

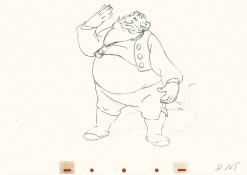

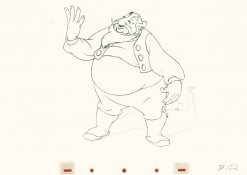

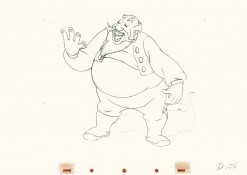

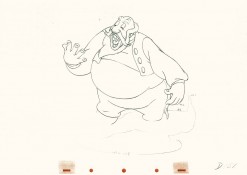

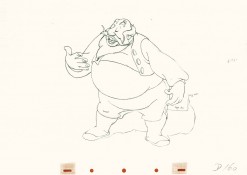

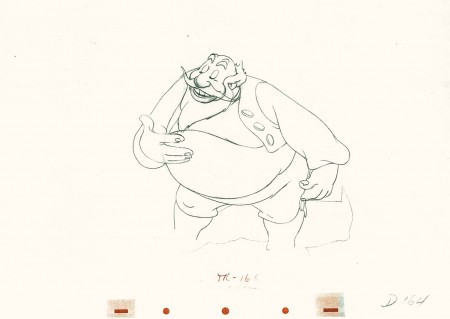

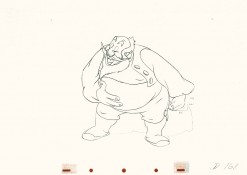

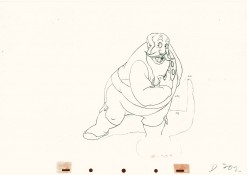

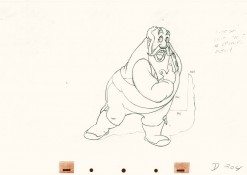

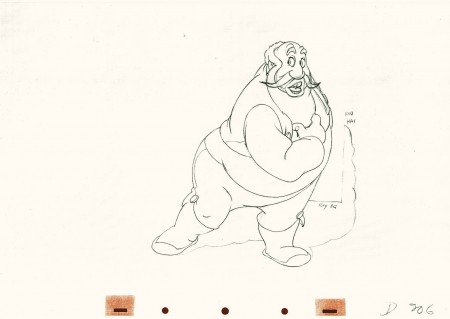

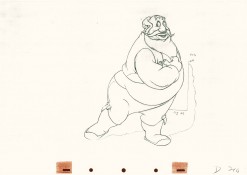

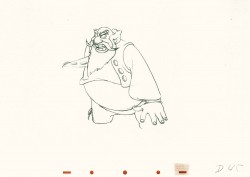

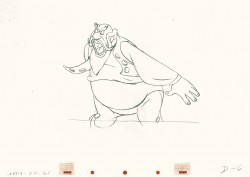

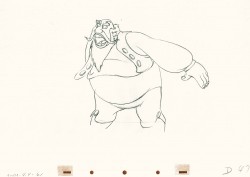

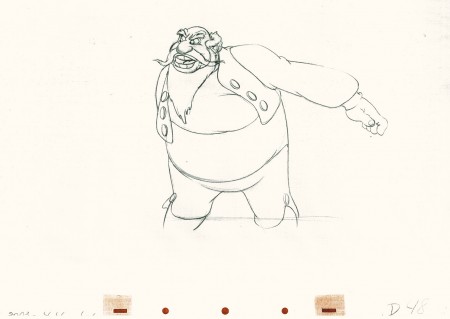

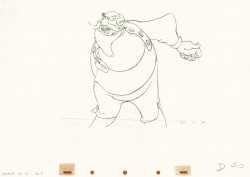

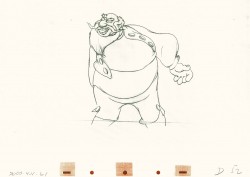

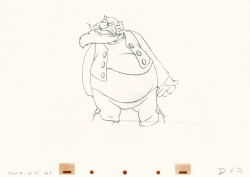

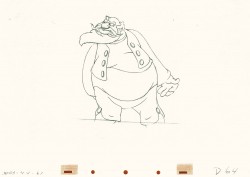

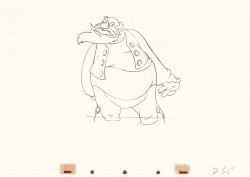

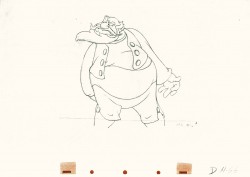

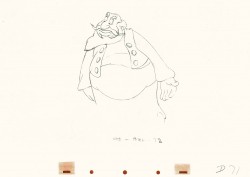

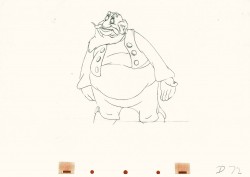

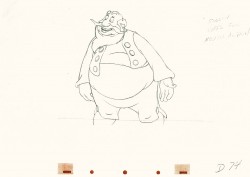

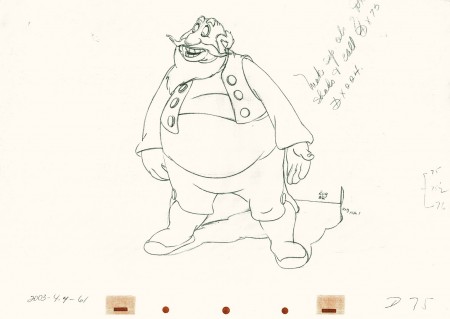

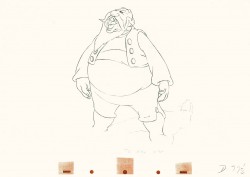

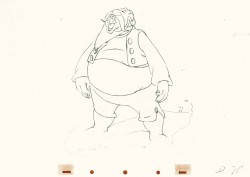

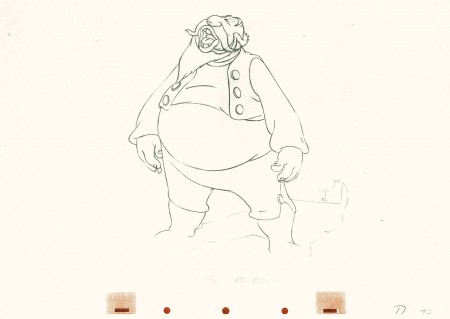

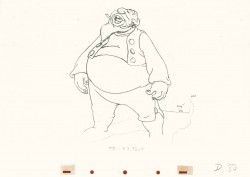

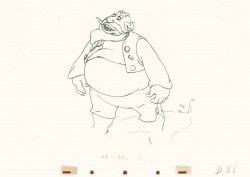

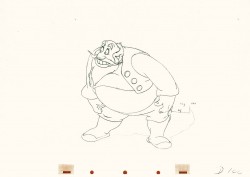

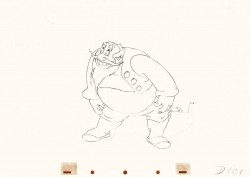

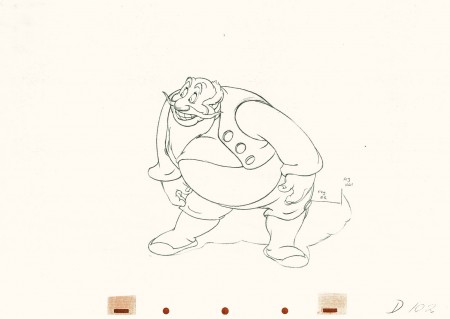

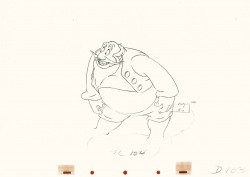

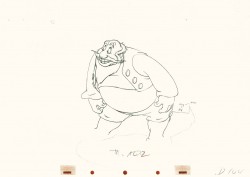

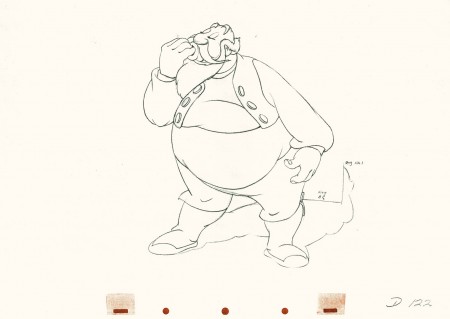

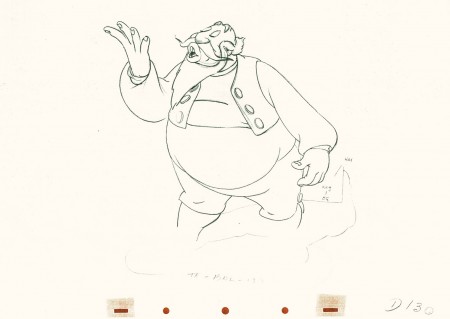

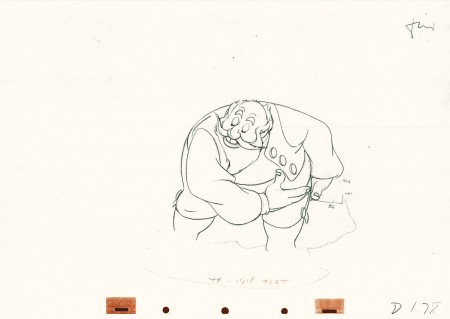

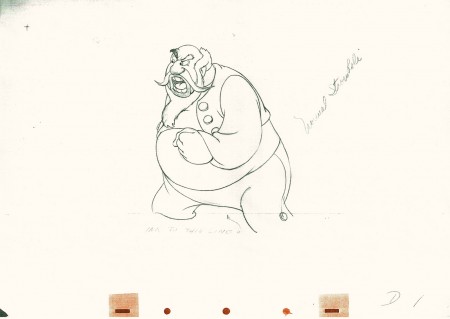

Tytla’s Stromboli – the Second half

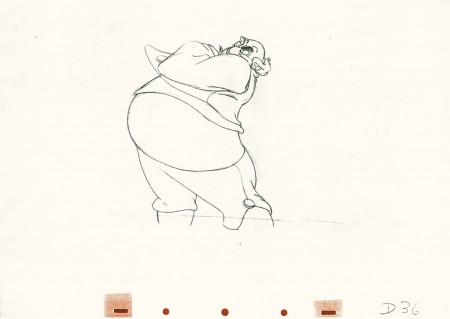

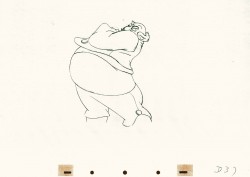

This is a continuation of yeserday’s recap post. Tytla was a genius and this scene is proof. Originally in five parts, here are the final three.

Nancy Beiman brought to my attention that T.Hee did some live action reference for Tytla as Stromboli. Here are some stills I located:

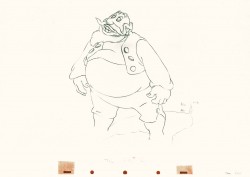

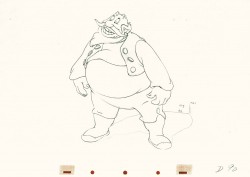

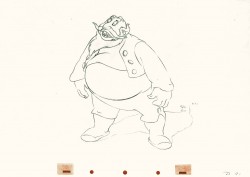

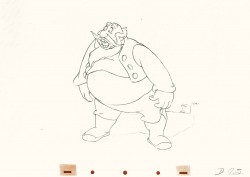

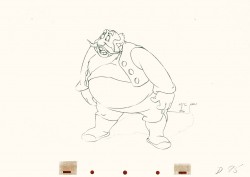

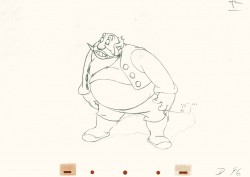

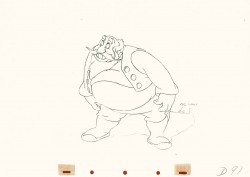

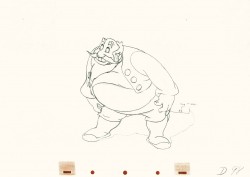

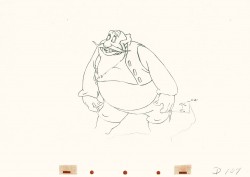

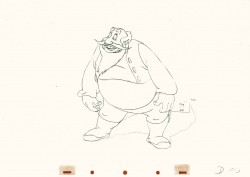

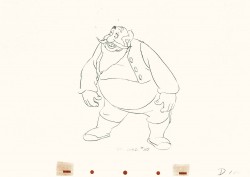

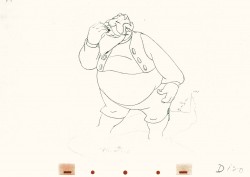

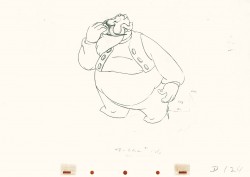

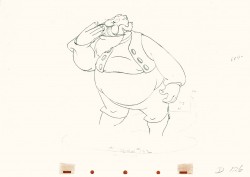

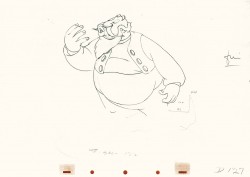

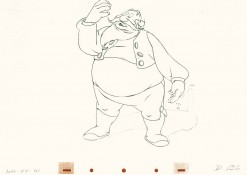

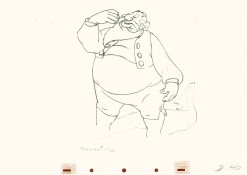

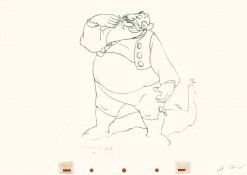

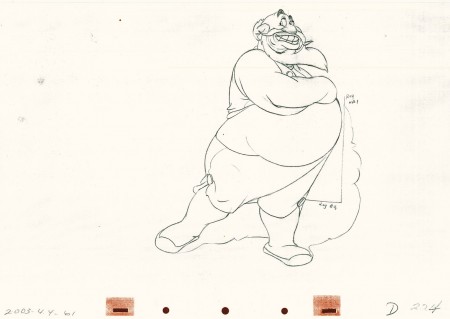

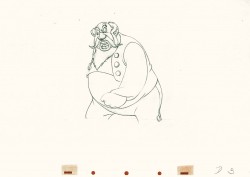

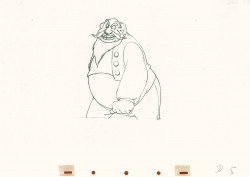

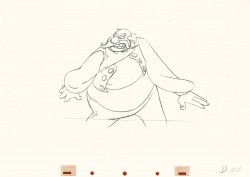

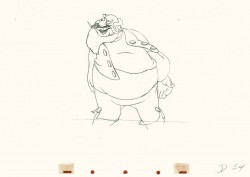

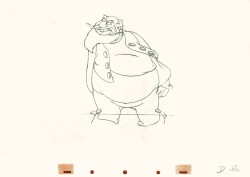

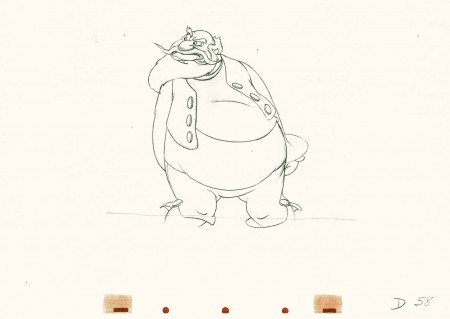

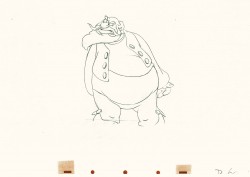

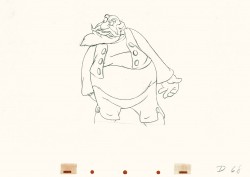

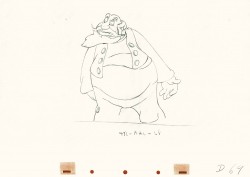

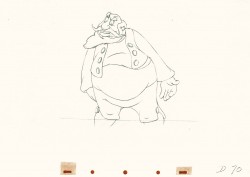

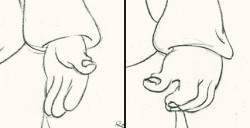

- This is part 3 of this large scene by Bill Tytla of Stromboli. The scene started in Part 1 with thoroughly frenetic anger from Stromboli. In Part 2 he tries to catch himself and get a grip on his emotions. Here in Part 3 he moves slowly and takes a 180° turn from where he started. The line against the curve. All this while playing out the lines from the scene. The drawing is stunning, the motion is brilliant, and the acting is the best animation has to offer. Those hands are just great; look at 126.

I pick up with the last drawing from Part 2.

86

86(Click any image to enlarge.)

87

87 88

88

Tytla made sure he firmly planted Stromboli’s feet (in part 2)

before he attempted this firm bow.

101

101

He’s made a solid line of the back, the strength of this move,

by using the left arm held firmly in place.

102

102

This is the bottom of the bow, now he goes back up.

104

104

All of the shapes change naturally in the bow, though it looks

as if it remains a solid. No noticeable change. Solid weight.

122

122

Watch the timing on the hand from here to #128

as Stromboli blows a kiss.

Many an animator today would pop it and call it animation.

130

130

(Click any image to enlarge.)

178

178

(Click any image to enlarge.)

Here’s the final QT of it all together:

Stromboli

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

David Nethery had taken my drawings posted and synched them up to the sound track here.

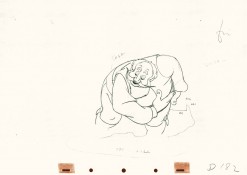

Animation &Animation Artifacts &Disney &John Canemaker &repeated posts &Tytla 20 Jul 2011 07:31 am

Tytla’s Stromboli – the First half

As stated last week, I’m recapping some of my Tytla posts from the past. This very long scene was originally in five parts. Today and tomorrow all five parts will be posted.

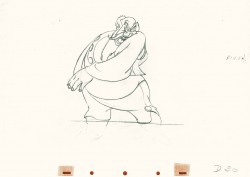

- Bill Tytla‘s work has to be studied and studied and studied for any student of animation. He was the best, and it’s pretty doubtful his work will be superceded. He brought beautiful distortion to many of the drawings he did, using it as a way to hammer home some of the emotions in the elasticity he was creating. Yet, the casual observer watching this sequence in motion doesn’t ever notice that distortion yet can feel it in the strength of the motion.

- Bill Tytla‘s work has to be studied and studied and studied for any student of animation. He was the best, and it’s pretty doubtful his work will be superceded. He brought beautiful distortion to many of the drawings he did, using it as a way to hammer home some of the emotions in the elasticity he was creating. Yet, the casual observer watching this sequence in motion doesn’t ever notice that distortion yet can feel it in the strength of the motion.

Four drawings (#1, 11, 22, & 48) that shift so enormously but call no attention to itself.

Brilliant draftsmanship and use of the forms.

Here we have the beginning: drawings 1-48. More will come in the future.

1

1(Click any image to enlarge.)

This note arrived from Borge Ring after my first post Bill Tytla’s scene featuring Stromboli’s mood swing:

- The Arch devotees of Milt Kahl have tearfull misgivings about Wladimir Tytla’s magnificent language of distortions. ‘”Yes, he IS good. But he has made SO many ugly drawings”

Musicologists will know that Beethoven abhorred the music of Johan Sebastian Bach.

yukyuk

Børge

My first post spoke a bit about the distortion Tytla would use to his advantage to get an emotional gesture across. It’s part of the “animating forces instead of forms†method that Tytla used. This is found in Stromboli’s face in the first post. In this one look for this arm in drawing #50. It barely registers but gives strength to the arm move before it as his blouse follows through in extreme.

There’s also some beautiful and simple drawing throughout this piece. Stromboli is, basically, a cartoon character that caricatures reality beautifully. A predecessor to Cruella de Vil. In drawings 76 to 80 there’s a simple turn of the hand that is nicely done by some assistant. A little thing among so much bravura animation.

There’s also some beautiful and simple drawing throughout this piece. Stromboli is, basically, a cartoon character that caricatures reality beautifully. A predecessor to Cruella de Vil. In drawings 76 to 80 there’s a simple turn of the hand that is nicely done by some assistant. A little thing among so much bravura animation.

Many people don’t like the exaggerated motion of Stromboli. However, I think it’s perfectly right for the character. He’s Italian – prone to big movements. He’s a performer who, like many actors in real life, goes for the big gesture. In short his character is all there – garlic breath and all. It’s not cliched and it’s well felt and thought out. Think of the Devil in “Night on Bald Mountain” that would follow, then the simply wonderful and understated Dumbo who would follow that. Tytla was a versatile master.

Here’s part 2 of the scene:

48

48 49

49(Click any image to enlarge.) The full scene with all drawings.

Click left side of the black bar to play.

Right side to watch single frame.

David Nethery had taken my drawings posted and synched them up to the sound track here.

Articles on Animation &Independent Animation &John Canemaker 07 Jul 2011 07:15 am

Caroline Leaf meets John Canemaker

The following is from the book, Storytelling in Animation, The Art of the Animated Image Vol 2. This is an anthology that was edited by John Canemaker which was published in conjunction with the Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

A Conversation with Caroline Leaf

This transcript has been abridged from the “Tribute to Caroline Leaf” that took place on June 11,1988 during The Second Annual Walter Lantz Conference on Animation.

JOHN CANEMAKER: When Caroline Leaf was beginning work on her masterful short film THE STREET, she told an interviewer, “I wanted to tell stories with my films, and I used animal legends and myths. Now I am working more on dramatic representation: dialogue, character and human problems. Perhaps dramatic expression is not ultimately the best form for animation, but still, I do not try to do what live-action can do better. The strongest influence on me is from literature rather than film. Kafka, Genet, lonesco, Beckett, have affected me most with the depths of their visions and world views and ways of breaking up time to tell a story.”

Caroline Leaf’s work is a wonderful synthesis of many of the storytelling techniques and animation methods discussed at this conference. She represents to me both the old and the new—the traditional and the experimental. Her use of direct, under the camera techniques and brilliant metamorphoses recall the pioneering works of James Stuart Blackton and Emile Cohl. Her perfect sense of timing and implementation of personality to individuate her characters echoes the balletic movements and emotional impact of the best of Disney. Within her films the imagery can be, at one moment, representational, and, in the transitions, non-objective abstraction. Caroline tells ancient folk tales as well as modern short stories. And she uses tools as primal as her hands to position paint on a smooth surface, or push sand grains into impressionistic symbols. She records her art with a modern invention, the movie camera, which allows her to bring inert designs and stories to life, a miracle never realized by artists until our century.

Caroline Leaf created her finest films at the National Film Board of Canada, a sympathetic but nonetheless corporate structure, in which she has managed to retain her individuality and personal signature. She is also a vital link in the list of women animators, designers and storytellers past and present who have made their way in a male-dominated field. From the simplest means she conjures a complex world of emotions, which is a talent found only in the work of the greatest artists. The transformation and alienation of a man turned into a loathsome cockroach; the variety of feelings triggered in family members by the imminent death of a loved one; the pathetic, ultimately self-destructive attempts of a lovesick owl to assimilate into a different culture; a small boy and assorted animals facing death in the form of an eerily omniscient wolf are some of the stories told with consummate skill in the films of Caroline Leaf. I’m so glad you’re here.

CAROLINE LEAF: I’m glad to be here.

CANEMAKER: I think that what’s extraordinary about seeing all your work together like this is to view your first film and to realize that it was all there—right at the very beginning. The good design, the sense of timing, and your whole bold approach to the medium is already there—your ideas about how to tell the story. That was your first film, wasn’t it?

LEAF: PETER AND THE WOLF (1969) is my first film. And I must say, I agree. I haven’t changed very much.

CANEMAKER: Grim Natwick always said that timing is the last thing an animator learns. It seems as if it was the first thing that you learned. Where did that come from? Were you trained in theatrics in any way?

LEAF: I’m not sure where it comes from. I think I make shapes and then try to keep them in balance. That’s my idea of how they move. I don’t know how to say where the timing comes from.

CANEMAKER: But you also know when to not make them move—you have a good sense about “holds.” When the cockroach was looking in the mirror, it went on and on, and you had the guts to keep it there without having it move at all.

LEAF: I’ve heard people talk about feeling the movement, and I know that I feel it. Sometimes I have to get up and act something out, or look in the mirror to see what it looks like when something happens. Working directly under the camera the way I do, there’s nothing between me and drawing the motion, and that helps with that. Intuitive expression of the movement, the timing. CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about story. In PETER AND THE WOLF, it’s very experimental. In many ways it is a first film because you get a feeling you’re trying to do a lot of different things. How did you approach the story in PETER AND THE WOLF? There’s just barely a theme of Prokofiev in the beginning —it’s all there, yet it isn’t.

LEAF: I’ve read a lot, and I’ve been most influenced by stories that I have some good gut feeling about. But then I like to go off and do my own thing with them. And on that film in particular—you’re right, I was trying to experiment; and the way I was working, I just had to divide things into segments. The ideas would evolve out of a little pile of sand and then go into wh’ite, and then a few days later I’d start a new sequence. So, it was pretty much the situation of wanting to use a story while not following it precisely.

CANEMAKER: And you use touches of personality, too: the little goose steps down but has a very particular way of doing it and it got a couple of laughs each time because it was so goose-like. Your characters have a lot of personality. Do you feel that personality guides story?

LEAF: Can they be equal?

CANEMAKER: Whatever you want! Anything you want, Caroline!

LEAF: I would say the story is important to me because it sets the limits and anything I do I don’t want to deviate from the feeling I want to generate from the story. The characters are the vehicles that express the stories, so they have to be right for each other. And I don’t indulge the characters, I don’t think, because I would get off track with my story, so I think I always sustain a line to keep the story moving along.

THE STREET (1976), adapted from Mordecai Richler’s story

CANEMAKER: Let’s talk about THE STREET (1976). How detailed was the original short story? Why did you approach it?

LEAF: I just liked the story, but there I had Mordecai Richler, a living person, a writer who lived not too far away from me, and I wanted to respect his writing. His story was maybe twenty pages, and at first I thought that to be respectful to the writer I should put everything onto film. And I found as I was working, the more I could pare away the words and just work with the imagery and be true to the feeling I was getting in the story, the better it worked on film. So there I was really trying to follow his story, but because film is a different medium, it came out in a different form.

CANEMAKER: Did you ever show it to him or did you confer with him during the making of it at all?

LEAF: No, he was strangely disinterested. He didn’t like the story too much, and didn’t care what I did with it, and never got in contact with me about it. I didn’t discuss it with him.

CANEMAKER: Did he ever see the finished film?

LEAF: I sent him a print and he never answered. I don’t know what he thinks of it.

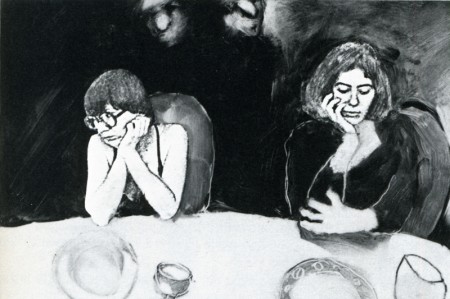

A family beset in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)

CANEMAKER: What about Kafka? Was your approach to pare away and get the imagery first in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA (1977)?

LEAF: The Kafka story is so complicated and wonderful. There I took just the element of what I was thinking about most—how horrible it would be to have a body, or the external part of one’s self that’s seen by the world be different from what’s inside one’s self, and not be able to communicate that. Since I’m a storyteller, I just worked with that one aspect of Kafka, so it’s quite different from his original story.

CANEMAKER: You really get into your characters; the emotion is there, it’s really extraordinary, I think. It’s just great. (Audience applauds.) Caroline doesn’t like to be interviewed, but she’s consented to this, and I appreciate it. I’d like to talk about the animated projects you’re working on now. One of them is a scratch-on-film technique.

LEAF: I’m just in the midst of starting two projects, and because I’ve been involved with live-action filming for a few years, and writing for live-action, now I’ve got a story that has all the characteristics and psychology and emotion of a live-action film, but I’m doing the images scratching on film. It is quite a restricted and crude image that I can make, but I find it exciting to find what I can tell of the story in imagery and how much I’ll have to rely on words.

Autobiographical insight in INTERVIEW (1979), co-directed with Veronica Soul

And the other project is a test of a computer animation program. It’s a small project, a program called Pastel, that was developed by the Film Board. They wanted to see how an animator would work with it, and what modifications it still needs.

CANEMAKER: Exciting. So you haven’t abandoned animation.

LEAF: No. Not at all. I just have had a hard time sitting still and doing it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I noticed in INTERVIEW (1979) that you had all those little thumbnails to the left [of the work under the camera]. Is that how you work, really planning it out in little sketches like that?

LEAF: Yes, that would be my detailed storyboard as I go along. I don’t storyboard too closely; to have done all the fun work, and to animate it, there are no surprises left. But I also need to know where I’m going since I work under the camera. If I take a wrong turn I can’fgo back. So, as I come to each scene, I do some little sketches, particularly to know what the characters look like in different positions, so I don’t get lost.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Your soundtracks have a powerful impact on the film. How much do you get involved? Do you sound-mix, or do you direct the actors and the dialogue?

LEAF: I am very involved with my soundtracks, and I enjoy working on them very much. The soundtrack for THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974) was the first one I really conceived and executed. But when I’m working at the Film Board, I’m not the mixer, and I’m not the recorder, usually. There’s a crew of people that do that for me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You’re able to tell a story mostly through images, yet in THE METAMORPHOSIS OF MR. SAMSA and THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE you alter the language. Why did you make those choices?

LEAF: The Kafka story wasn’t in the public domain and I didn’t have the rights to the translation, so I made up a kind of gobbledy-gook language for that. And the Eskimo film was not a language you understood, either. They were speaking the Eskimo language.

CANEMAKER: THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE is exquisite. Sometimes in animation there are images you want to continue on and on and on. That scene of the birds flying, and the sound of wings getting as big and close as they are, and then they’re flapping for a while in front of you. I could watch it for a long time.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: In that vein, I’d like to know how long you studied the animals to get their movements so perfect.

LEAF: I don’t study animals. I don’t go to the zoo. And in fact my movement isn’t very realistic. I think you can make it convincing. It fits the shapes, I think. I’ve never really looked to see how birds fly, and it’s kind of awkward in fact how they do, but it somehow works.

CANEMAKER: In several films you have a character who will take a step and then the legs would switch in some unnatural way—but somehow it works. In THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE I think there’s a section where that happens.

LEAF: I know it happens in THE STREET once — arms change . . .

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Why are you working in Canada? Economics?

LEAF: Yes, the Film Board is quite a special place. It’s allowed me to do the films that I’ve done, which I don’t think I could have done down here.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Because no one’s going to buy them? Or distribute them?

LEAF: It’s because of the problem with the distribution of short films. Ask any of the independent animators who’ve spoken here. Most of them are teaching, and it’s hard to have films seen. I found it is also hard at the Film Board. It’s difficult to have short films seen, and I’m not happy with the distribution, but I’m paid a salary there, and I’m quite free. Not totally free, because it’s a government film agency, and there are restrictions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What kind of restrictions?

LEAF: I find there’s a rather insidious way of thinking that grows on one working in a place like that. The most obvious thing is that it’s not possible to experiment; or it’s not easy to do an abstract film, because they’re always concerned about their market, which is an educational market. And besides that they’re very sensitive to not provoke any public outrage, or outcry, so they take a middle road. Nothing should be too controversial. I can read stories and know right away, this is something that could be done at the Film Board or not. One isn’t free to do exactly what one would like to do but one can mold it to be close enough to be satisfying.

Exquisite images of geese in flight in THE OWL WHO MARRIED A GOOSE (1974)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Does the Film Board expect to make their money back on films?

LEAF: No. The income they receive from the films goes back into production, but the Board receives government money each year. They have an annual amount given to them from Parliament. It’s voted each year.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Has it been growing?

LEAF: It’s been shrinking in recent years. So the place has shrunk a lot. Just last year they were voted an increase, which might just bring them equal with inflation for the first time in a few years. But everyone takes it as a vote of confidence.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Who owns the films you made while you were on salary?

LEAF: The Film Board owns them. I don’t have any rights to them at all.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do you think that your technique would be used in any major projects, for instance in a Disney feature?

LEAF: Well, I’ve seen my way of transforming used in eel animation. But actually the way I work, under the camera, I don’t think I can work as a team in that way. So it would be hard to make a long film using my technique, and get everyone working in a way that looks the same, This winter I did a commercial in New York, arid that was the first time I’d really found that my under the camera technique could work commercially. Because normally I would do some designs and then I would start, and I’d go to the end. And here I didn’t have any way to fit into the system of checks and balances that are used commercially. The client couldn’t see beforehand what I was going to do. But I evolved enough different systems of storyboarding that they felt reasonably secure, when I started animating, what they’d get when I’d

finished.

CANEMAKER: If it were possible to direct other people in your technique, would you be interested in doing a feature?

LEAF: No, I wouldn’t. I can’t imagine directing other people, and also I have a lot of fun when my fingers are doing it and I discover for myself little things. That’s what keeps me going. And I don’t know what it would be like, if it would be enjoyable to direct other people.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you ever used colored sand?

LEAF: I got tangled in knots one time trying to use colored sand. When you use colored sand—colored anything—you put a lot of time into keeping your colors separate, so they don’t all become like mud. And keeping colored sand grains separate was very difficult! I gave it up quickly.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you had students or apprentices pick up on your technique and pursue it in their own pictures?

LEAF: There are a few people that have worked in the same materials that I’ve worked in, but not as many as I’d like. And I haven’t had students. I haven’t taught.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Will you be working on a team for the computer animation?

LEAF: This is just a small project, and I’m alone with the guy that developed the program. We’re working together. He listens to my complaints and makes alterations. I’m amazed sometimes by what he’s done, but it’s not really a team.

CANEMAKER: I would like to thank Caroline Leaf for being here.

LEAF: Thank you for being here!